I INTRODUCTION

The aim of this paper is to examine the habit of displaying building inscriptions in the orbit of Carthage in the second century a.d., and in particular the prominent place of religious architecture. Building inscriptions (that is, texts that record the erection, extension or restoration of structures) commonly include information on the building and the person who built it, including their career and family, and often also the cost of the project. Moreover, the customary inclusion of wishes for the health of emperors makes many of them securely datable. They are especially common in Tunisia and eastern Algeria, where they have been employed to reconstruct the built environment of Roman towns, tracing their development over time.Footnote 1 They have also been used to assess the economic vitality of both the region and the Empire as a whole — most famously by Richard Duncan-Jones but also by many others.Footnote 2 These approaches are predicated on the assumption that all public buildings were furnished with such inscriptions, and that the corpus of surviving texts corresponds reasonably well to actual construction. This, however, is not the case: many more inscriptions come from buildings that were considered opera sacra (henceforth sacra) — that is, shrines and monuments dedicated to emperors and gods. Of 514 classifiable building inscriptions from this region,Footnote 3 texts that refer to sacra account for at least 75 per cent.

Not all building types were inscribed in the same ways, with ramifications for how surviving building inscriptions can be analysed. It has not gone unnoticed that this requires caution; for instance, Edmund Thomas and Christian Witschel have shown that building inscriptions often exaggerate the extent of the work undertaken;Footnote 4 Paul-Albert Février pointed out that their survival is highly uneven, making them unsuitable for broadly conceived quantitative approaches.Footnote 5 However, the methodological problems run deeper, touching on what building inscriptions were and what they were meant to do. The first part of this paper examines the chronology, geography and agency of building inscriptions from one part of Roman North Africa, showing that the practices of epigraphic commemoration differed significantly between different building types and categories of builders, and also between different communities. Three aspects stand out: first, sacra were more regularly inscribed than other buildings. Inscriptions from amenities such as baths are rare at any time, and they differ in key respects from those associated with sacra. Second, inscriptions from sacra account for a larger proportion of the samples in small towns than in the most populous and important cities. These patterns cannot be explained by the uneven preservation of inscriptions. Third, inscriptions from sacra increase dramatically in the second century and plummet under the early Severans, in ways that have no parallel among texts from secular buildings.

This strongly suggests that different epigraphic practices obtained for different types of buildings, and that it is relevant to talk about an ‘epigraphic habit’ affecting the material. This idea was first introduced by Ramsay MacMullen, who observed that communities and individuals adopted stone media to a varying degree, and that their deployment was not consistent over time.Footnote 6 The idea has been revisited many times, by Elizabeth Meyer, Barbara Borg, Christian Witschel, Michael Kulikowski and Greg Woolf among others,Footnote 7 who have emphasised the social factors determining the use of epigraphic media. In particular, the debate has nuanced the approach to the so-called third-century crisis, a time when stone inscriptions went widely out of use in most parts of the western Empire. The absence of inscriptions cannot thus be treated as straightforward evidence for the absence of people or resources. Somewhat surprisingly, the idea has not been fully exploited for building inscriptions, even though these have contributed much to the idea of a Severan floruit followed by a drastic downturn in prosperity.Footnote 8 Scholars who have sought to counter the notion of ‘crisis’ have not challenged the assumption that fewer building inscriptions indicate fewer construction projects, but have turned to other explanations. For instance, Hélène Jouffroy argued that the lower number of building inscriptions represented a natural lull in public construction after decades of saturation,Footnote 9 while Barbara Borg and Christian Witschel suggested that changing arenas of self-representation diverted resources away from public buildings.Footnote 10 Although revisionist, these theories are still broadly predicated on a one-to-one relation between buildings and building inscriptions. This is the case also in a recent overview of the ‘epigraphic habit’, in which dwindling building inscriptions are again associated with economic difficulties.Footnote 11

However, a thing built was not by default a thing inscribed. The second part of the paper explores the reasons why some types of projects were felt to require inscriptions more than others, and what such inscriptions meant to those who posted them. I analyse the many inscriptions from sacra from a socio-political perspective, seeking to identify the roles they played in contemporary society. Importantly, inscriptions are not buildings, but records of events, and there are reasons to doubt that the event was, in all cases, the erection of a building. I argue that the reasons to commemorate a building project with an inscription were not exclusively tied to its cost or prestige, but depended on its relation to local political institutions. These institutions not only governed the use of inscriptions in public spaces, but were also intimately linked with religious architecture to an extent that has not been acknowledged. In particular, local political advancement was associated with building sacra, which contributed to making such buildings more visible in the epigraphic record than other structures. To conclude, I argue that the reasons why the study area shows such a remarkable concentration of inscriptions from sacra during a few decades can be found in the institutional framework of the region and the ambitions of its elites. I connect the rise in numbers of such testimonies with intensified peer-to-peer competition generated by the presence and stature of the city of Carthage, and by the openness of this city's political institutions to elites in surrounding towns. ‘Town’ means a self-governing political community with its own council and magistrates, but many towns were subordinated to larger cities (especially Carthage) in an intricate system of dependency. The dissolution of such urban hierarchies under the early Severans directly affected the career prospects of small-town African elites, and by extension the epigraphic commemoration of sacra. There is little to indicate that they also affected the commemoration, or indeed construction, of other buildings.

II THE DOMINANCE OF SACRA

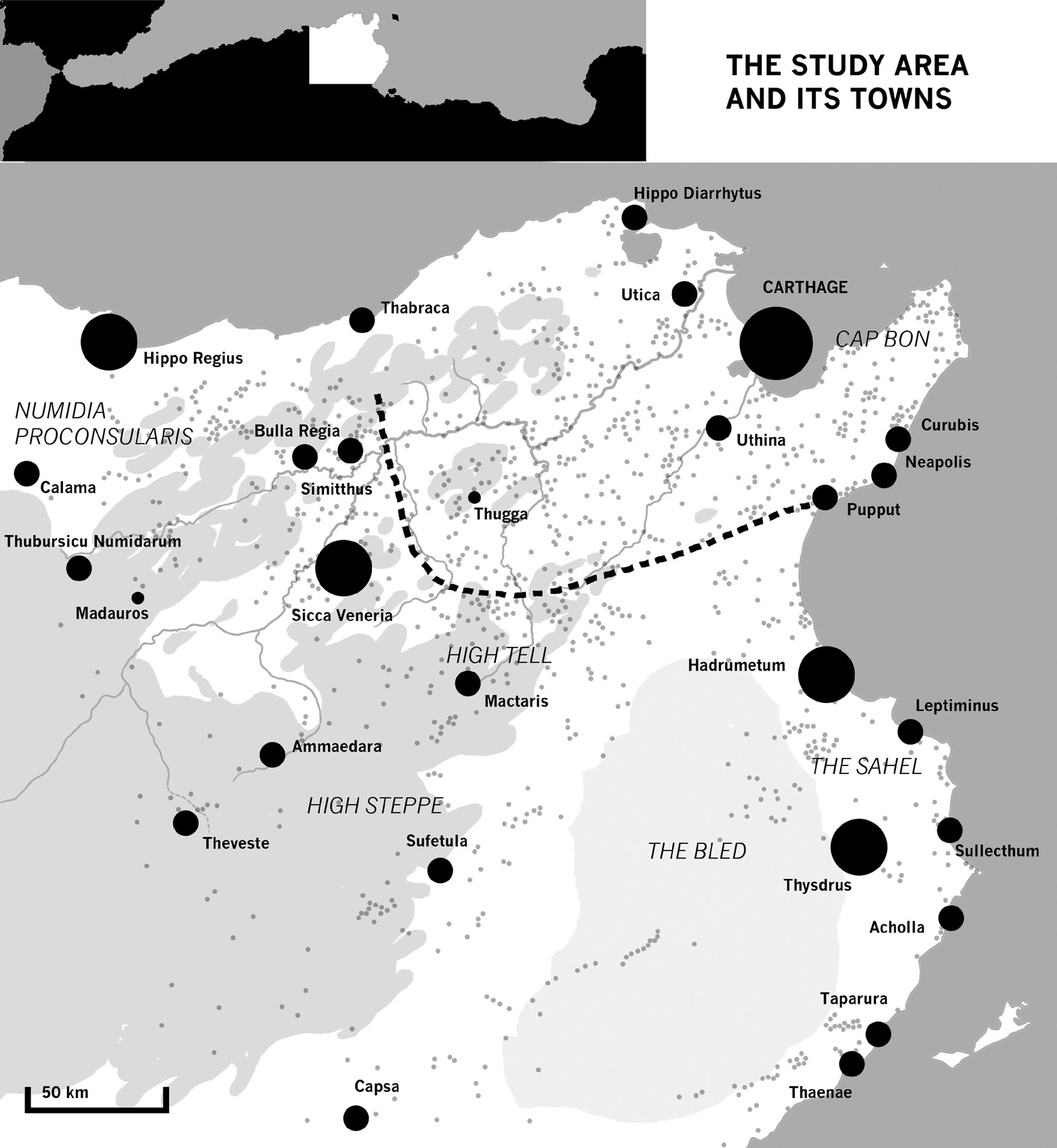

The sample of texts that forms the basis of this study comes from an area that roughly corresponds to the late Roman provinces of Africa Proconsularis and Valeria Byzacena, the first part of Africa to come under Roman occupation and the longest to remain so (Fig. 1). The area can be described as the enormous territory of Carthage together with a periphery that had its main lines of communications with this city and its hinterland. Some of these routes and towns had a military past, but after Trajan moved the Legio III Augusta to Lambaesis in Numidia, the area lacked military presence save for garrisons at Carthage and Thysdrus, and its towns were not fortified. It stood apart from neighbouring regions also in terms of urbanisation: the extreme density of urban settlement had few parallels empire-wide, and none in Africa. This area was very rich in epigraphic production, especially the north-eastern heartland. I have collected 704 building inscriptions from the region, dating from the Republic to the reign of Diocletian, although many of them are too fragmentary to provide much information.Footnote 12

FIG. 1. Map of the study area. (Source: Barrington Atlas). It comprises the territory of Carthage and its neighbouring regions. Where convenient, I have used modern names, as the ancient ones are, for the most part, unknown. Numidia Proconsularis is a late antique term for an area that today lies in two countries. Borders shifted also in Antiquity, but the area retained its integrity, flanked to the west and south by a belt of Flavian roads and towns. The most striking characteristic is its great number of small towns, represented as grey dots. Black dots represent major towns, with the relative diameter reflecting their status, based on their administrative roles, amenities and the size of their populations and territories (see the discussion below). The dashed line marks the border of the territory of Carthage, the so-called pertica, as far as it is known.

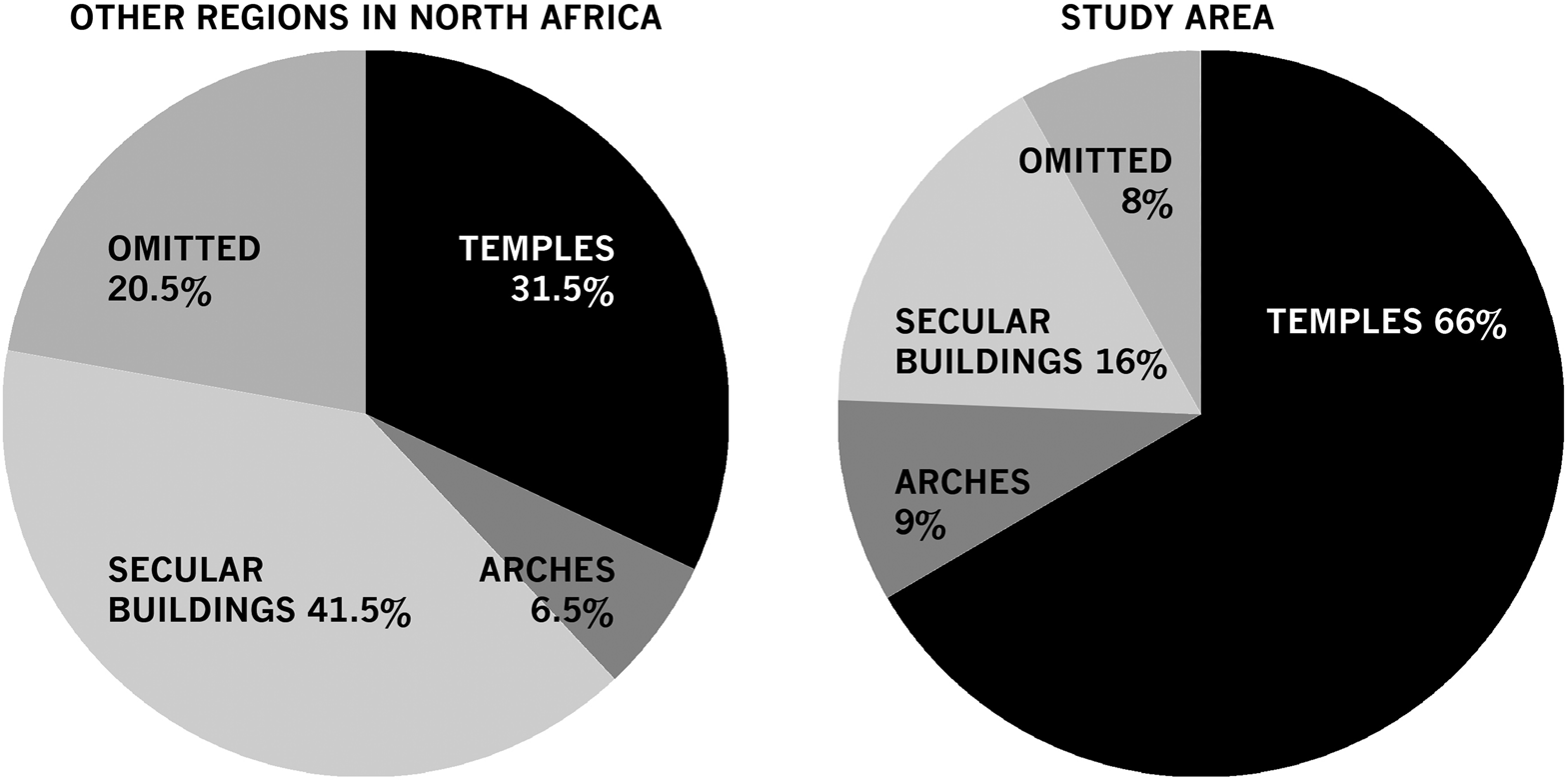

Although building inscriptions from this area have received a fair share of attention, it has not been acknowledged that the vast majority of them refer to structures dedicated to gods and emperors (see Fig. 2b). Most inscriptions are fragmentary, but of the 514 items that are complete enough to reveal what was built, well over two-thirds (341) refer to temples, whether built afresh, restored, embellished or augmented. A large share of the rest (forty-seven) refer to arches dedicated to emperors, bringing the proportion of sacra up to three-fourths of the sample. Furthermore, of inscriptions that deliberately omit the building (forty-two items), eleven were found in situ on arches. All types of secular buildings together make up a meagre 16 per cent, even at the most inclusive.Footnote 13 Moreover, this record is inflated by the practice of posting multiple inscriptions that commemorate the same building project, known to scholars working on African inscriptions as gemellae.Footnote 14 For instance, seven inscriptions that refer to markets represent only three discrete construction projects.Footnote 15

FIG. 2. Proportion of sacra to secular buildings (a) in the Mauretanias, Numidia and Tripolitania (400 items, source: Saastamoinen Reference Saastamoinen2010a) and (b) in the study area (514 items, source: Appendix). ‘Omitted’ indicates that the building is deliberately excluded from the text.

The numbers are puzzling, for many reasons. The towns clearly did not consist of temples and arches alone. They had beautifully paved streets, but only (at best) four inscriptions from more than three centuries feature anyone taking credit for them.Footnote 16 There are ruins from baths in even the smallest towns but only nine inscriptions from them before the reign of Diocletian.Footnote 17 Few other building types are represented in even a handful of texts.Footnote 18 More than sixty African amphitheatres have been attested — as many as three in Thysdrus alone — but before a.d. 284 not a single building inscription in this area proclaims who built one.Footnote 19 Meanwhile, there are almost 400 inscriptions from temples and arches.

Arches are an African phenomenon, attested in the smallest towns and even on imperial estates. They can be regarded as buildings, comparable to shrines dedicated to imperial virtues and victories, but they can also be categorised as particularly imposing statue bases and be counted among the several hundred imperial statues attested in the area.Footnote 20 Arches mark out one end of a spectrum of sacred buildings with sanctuaries at the other end, including minor structures such as sacellae or aediculae. That they belong to the same category is also indicated by the language of their inscriptions: while the miscellany of texts from other buildings show little conformity, those from sanctuaries and arches follow easily recognisable conventions. A great many fragmentary inscriptions most likely belonged to this category as well, using more or less the same format. Such inscriptions commonly include imperial dedications, the names, careers and families of the builders, the cost of the projects and the dedicatory ceremonies. The following examples illustrate the range, from the fairly succinct to the more detailed:Footnote 21

CIL 8.14851, Tuccabor, arch: Imp(eratori) Caes(ari) divi Hadriani f. Antonino Aug(usto) Pio p(ontifici) m[ax(imo) trib(unicia) pot(estate) --- co(n)s(uli) --- p(atri) p(atriae)] | Sextilius Dextri fil. Celsus arcum a fundamen[tis opere quadrato?] | cum gradibus et statua s(ua) p(ecunia) f(ecit) id(em)q(ue) ded[icavit]. | D(ecreto) d(ecurionum).

To Caesar Antoninus Augustus Pius, son of the deified Hadrian, pontifex m[aximus, holder of tribunician power for the (…) time, consul for the (…) time, father of the country], Sextilius Celsus, son of Dexter, constructed an arch from its foundations, [using opus quadratum,] with steps and a statue, for his own money, and he also dedicated it. (Posted/undertaken) by the decree of the decurions.

AE 2012.1882, Uchi Maius, temple: Cae[lesti Aug(ustae) sac(rum)] | pro salute Imp[p(eratorum) Caess(arum) Aurelior(um) Antonini | et Veri, Armeniacor(um), Medicor(um), Part(hicorum) max(imorum)] | res publica U(chitanorum) M(aiorum). [D(ecreto d(ecurionum) p(ecunia) p(ublica) f(ecit)]. | C. Furnio Fausti[no L. Propertio Rogato magg(istris) pag(i)].

[Sacred to] Cae[lestis Augusta]. For the health of the Emp[erors and Caesars the Aurelii Antoninus and Verus, greatest conquerors of the Armenians, the Medes and the Parthians], the respublica of Uchi Maius built (the temple) [by the decree of the decurions and for public funds], in the year when C. Furnius Faustin[us and L. Propertius Rogatus were magistri pagi].

AE 1968.595, Musti, temple: Plutoni Frugif(ero) | Aug(usto) genio Mustis | sacr(um). Pro salute | Imp(eratoris) T. Aeli Hadrian[i A]ntonini | Aug(usti) Pii M. Corneli[us] M. f. | Cornelia Laetus flamen | perpetu(u)s IIvir sacerdos | Caelestis et Aesculapii | publicus cum pro honore | flamoni perp(etui) HS X (milia nummum) taxas|set et ob honorem IIvir(atus) | HS II (milia nummum) inlatis aerario HS III (milibus nummum) | statuam aeream posuit et in templo Caelestis portic(um) columna|rum IIII ampliata pecu[ni]a fe|cit d(ecreto) d(ecurionum) idem q[uoqu]e [de]dic(avit) ampli|us in eode[m templo] porticum | avitam [v]e[t]u[state conl]absam [co]|lumnis [--- adiecta] pecuni[a] | res[tituit].

Sacred to Pluto Frugifer Augustus, the genius of Mustis. For the health of the Emperor T. Aelius Hadrian[us A]ntoninus Augustus Pius, M. Corneli[us] Laetus, son of Marcus, of the tribe Cornelia, flamen perpetuus, duumvir, public priest of Caelestis and Aesculapius, after he had paid 10,000 sesterces in exchange for the office of flamen perpetuus and 2,000 sesterces for the sake of the office of duumvir, with 3,000 sesterces paid in to the treasury he raised a bronze statue, and for additional money built a portico of four columns in the temple of Caelestis, by the decree of the decurions, and he a[lso ded]icated the same. Furthermore, in the sam[e temple] he res[tored] the ancestral portico which had [collapsed from old] age, with columns […] money […].

It appears that, in the Carthaginian hinterland, structures raised in honour of gods and emperors merited inscribing to an extent that other buildings did not. This is not limited to original construction: every addition to a sanctuary, be it an ornament, a column or some steps for a staircase, could be broadcast in minute detail.Footnote 22 This is exceedingly rare for other types of buildings. Inscriptions from multifunctional buildings foreground their religious aspect, such as the four gemellae that mention a macellum as part of a shrine to Mercury.Footnote 23 Such precincts were no doubt often used as markets, as Elizabeth Fentress plausibly suggested for the large sanctuary at Vazi Sarra, but it is as sacra that they are inscribed.Footnote 24

As a comparison, a sample of building inscriptions from Asia Minor examined by Arjan Zuiderhoek covers the whole gamut of public buildings in reasonable proportions to the monumental fabric of the towns.Footnote 25 Although sanctuaries form the largest category (at roughly 25 per cent), they do not dominate the epigraphic landscape to even remotely the same extent as here. The hinterland of Carthage is also distinct from the rest of Roman North Africa, which does not show the same extreme imbalance between sacra and secular buildings. Using 400 classifiable texts from the Mauretanias, Numidia and Tripolitania in the catalogue of inscriptions assembled by Ari Saastamoinen, I calculated the proportion of sacra to other buildings (Fig. 2a), with very different results in comparison to the study area (Fig. 2b). Temples and arches together made up less than 40 per cent of the total, leaving plenty of room for other buildings.Footnote 26 The breakdown of buildings documented in African building inscriptions outside the study area is not too dissimilar from Zuiderhoek's.

Political borders shifted over the centuries, but the tendency for the epigraphy of the study area to stand apart from other regions stayed the same. Its idiosyncratic character was not the product of internal social or political homogeneity; its towns and sub-regions were diverse both in terms of identity and legal status. The Sahel was home to old and wealthy Libyphoenician coastal towns, while the High Tell had Royal Numidian roots. A military past clung to several western towns, which were also points of contact with Berber tribes. The region housed a wide array of communities, from colonies and municipalities to subordinated towns and estate villages, often connected through complex chains of dependency.Footnote 27 The vast territory of Carthage incorporated a bewildering range of towns of varying status (on which more below), and nested within it were also colonies, more or less integrated with the larger city. Even so, it appears that the communities in the region shared in a particular epigraphic practice which distinguished it from other parts of Africa and the Empire.

III THE CHRONOLOGY OF SACRA COMPARED TO OTHER BUILDINGS

The study area also stands out with respect to chronology: it is the epigraphy of this region that has contributed most to the picture of a sharp peak in African building inscriptions in the second century and a dramatic fall in the early third. In Numidia, the record slumps less, and in Mauretania, it peaks in the mid third century. Moreover, in the study area these changes only affect sacra. They increase steadily through the second century, peak at the turn of the third, and then drop to zero by 217 at the latest. Numbers recover somewhat under Severus Alexander, Gallienus and Diocletian, but not to their Antonine heights. In the late third century, stone inscriptions appear to be used mainly for structures celebrating emperors, such as imperial arches, shrines to imperial virtues or to Sol in the reign of Aurelian, a cult with no previous history in the area.Footnote 28 After 305, all building inscriptions disappear, but, following a hiatus during Constantine's reign, inscriptions from secular buildings re-emerge. By then the public dedication of sacra through stone inscriptions was a thing of the past, and fourth-century inscriptions will not be discussed here.

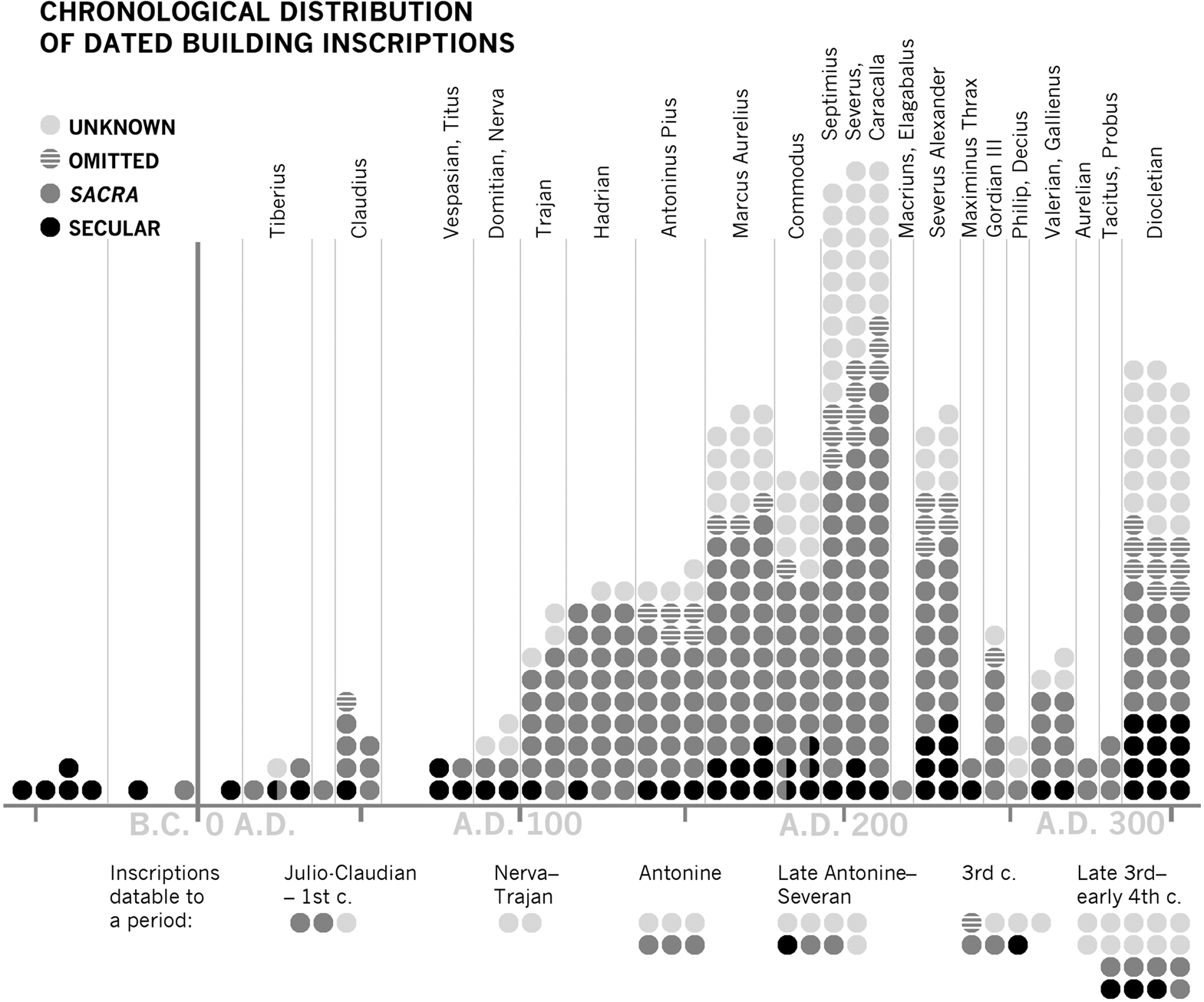

Conversely, although inscriptions from secular buildings are few from any period, they are as rare in the first two centuries as in the third or fourth (Fig. 3), and there is little to suggest change. They are proportionally more common in the Republic, but this impression is produced by the absence, as yet, of inscriptions from shrines. Minor concentrations occur — for instance, theatres appear in the reign of Marcus Aurelius — but apparent increases of secular buildings in his and Alexander Severus’ reigns are, by and large, the products of gemellae. The largest category of secular buildings — baths — are attested in the Republic and in the reigns of Domitian (probably), Marcus Aurelius, Septimius Severus, Gallienus and Diocletian. There is a significant concentration of secular buildings in the reign of Diocletian, but this is a time when all types of building inscriptions make a striking, if chronologically limited, comeback. This suggests a (short-lived) change in overall inscribing practices rather than a genuine change in patterns of building activity. Diocletian's reign is thus best treated separately.Footnote 29

FIG. 3. Distribution of dated building inscriptions, with each text represented by a dot (source: Appendix). ‘Omitted’ indicates that the building is deliberately excluded from the text. The four ‘split’ items dating to Commodus represent four gemellae commemorating a macellum-and-shrine project. The inscriptions are organised by reign, which in most cases is the only date available. Organising by, for instance, quarter-centuries would be more arbitrary, and would also obscure peaks and falls, by spreading high records over periods with fewer inscriptions. My aim here has been to make each individual item visible, at the cost of some precision given the differing lengths of reigns — but distortions are minor. Below the timeline are texts datable only to a period, showing that these conform to the more precisely dated texts above in terms of building types.

Arguments that seek to account for the changing frequencies of building inscriptions over time have generally failed to recognise that these do not involve all types of buildings. It is tempting to see the peak under Diocletian as the necessary maintenance of public architecture after a long period of neglect, not least since many of the inscriptions from this period record the restoration of amenities. A similar ‘natural’ development has been suggested by Hélène Jouffroy, who argued that the slump in the third century reflects intense building activity in the second, and by Gabriele Wesch-Klein, who suggested a peak in the first century.Footnote 30 However, what was inscribed en masse in the second century (temples and arches) is not what was restored in the late third (amenities). Moreover, aside from the fact that there is no accumulation of — supposedly authoritative — testimonies to secular construction in either the first or the second century, restorations are at all times more common for inscriptions recording anything but sacra from the earliest instances to the last.Footnote 31 Even so, they remain so few that, although restorations of sacra are proportionally less common, these are still more plentiful in absolute numbers.

It is sacra that generate the changes in the record on which arguments that correlate rates of public construction with the health of local communities rely. Meanwhile, inscriptions from the buildings most central to these arguments — amenities and other secular buildings — show little evidence for change over the centuries. Perhaps one reason that this has gone unnoticed is that the latter are so few. They have not been treated separately from sacra, which has masked the fact that they are not distributed in the same ways. Another reason is the common practice of equating building inscriptions with buildings, including them in catalogues of construction where they are mixed with the undated remains of all types of structures. This evens out the imbalance in the epigraphic record, and reproduces its timeline, while giving the impression that the archaeology confirms it.Footnote 32 African buildings can rarely be dated without inscriptions, and are often attributed to the late Antonine/early Severan period on the basis that much appears to have been built then, thus adding to this impression.Footnote 33 A good example is the amphitheatre of Uthina, which was long considered ‘Severan’ until a statue to its builder was discovered that revealed it as Hadrianic.Footnote 34

This hints at a third reason why few have questioned that the Severan peak in building inscriptions reflects a peak in actual construction, and that it extends to all kinds of buildings: it fits with the common notion that this period was particularly prosperous for Africa, thanks to the early Severan emperors’ personal relation to the region. However, it is possible to push back against the idea that these rulers favoured this particular part of Africa. It had no military installations to attract imperial attention, there are no attested benefactions by Severus or Caracalla in the area (as in Tripolitania), and most historians with an African focus interpret their attitude towards Carthage as hostile.Footnote 35 Besides suspicion against the growing power of the city's elites, one may note that Clodius Albinus hailed from Hadrumetum which had strong ties to Carthage, and that Severus often punished cities that had supported his enemies.

There are also reasons to question that the peak in inscriptions from sacra fell in their reigns rather than under the late Antonines. Severus and Caracalla are over-represented in the epigraphic record through their long and idiosyncratic imperial titles — in one instance 158 words — which makes for more, and more readily identifiable, fragments.Footnote 36 Conventions have also favoured the Severans, such as making a.d. 235 a terminus ante quem for the inclusion of tribus in names even though it is still attested under Aurelian, if not later.Footnote 37 Treating all ‘Severans’ from 193 to 235 as a bloc obscures how drastic the decrease in numbers is, and that it fell in the middle of this period rather than after it. It is not (just) the product of an unusually thorough damnatio memoriae of Elagabalus: mid-century texts are different in several respects. One might even reframe the reign of Caracalla as the decisive moment for the demise, rather than the peak, of the tendency to inscribe sacra in this area.

This poses problems for connecting the building inscriptions with any ‘third-century crisis’: a.d. 217 is not for the most part treated as its onset, and the fairly prolific reign of Gallienus is usually viewed as its nadir. The record for the mid to late third century is not lower than the Julio-Claudian or Flavian periods. Nor does the archaeology of the area's towns — if analysed independently of building inscriptions — suggest that these declined in the third century. According to Anna Leone, signs of deterioration such as lack of maintenance, encroachment on public spaces or shrinkage of urban areas are not widely attested until the end of the fourth century at the earliest.Footnote 38 The sharp oscillations in the epigraphic record at the onset of Late Antiquity suggest changes in epigraphic production rather than the frequency of construction: it seems unlikely that the area was suddenly prosperous in 284 only to be utterly devastated in 305, especially seeing that the following decades ushered in the strongest economic development that this part of Roman North Africa ever enjoyed.Footnote 39

IV THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE INSCRIPTIONS

A close look at the towns of the region and their separate dossiers of inscriptions reveals that inscriptions from shrines and arches are not evenly distributed over the area. Zuiderhoek's study indicates that in Asia Minor the part is consistent with the whole, with about the same proportions of buildings in separate communities as in the region, but this does not appear to be the case in my North African study area. Sacra make up a larger share of the texts from smaller, inland towns than they do in larger cities on the coast. This and other factors suggest that towns of different status used such texts differently.

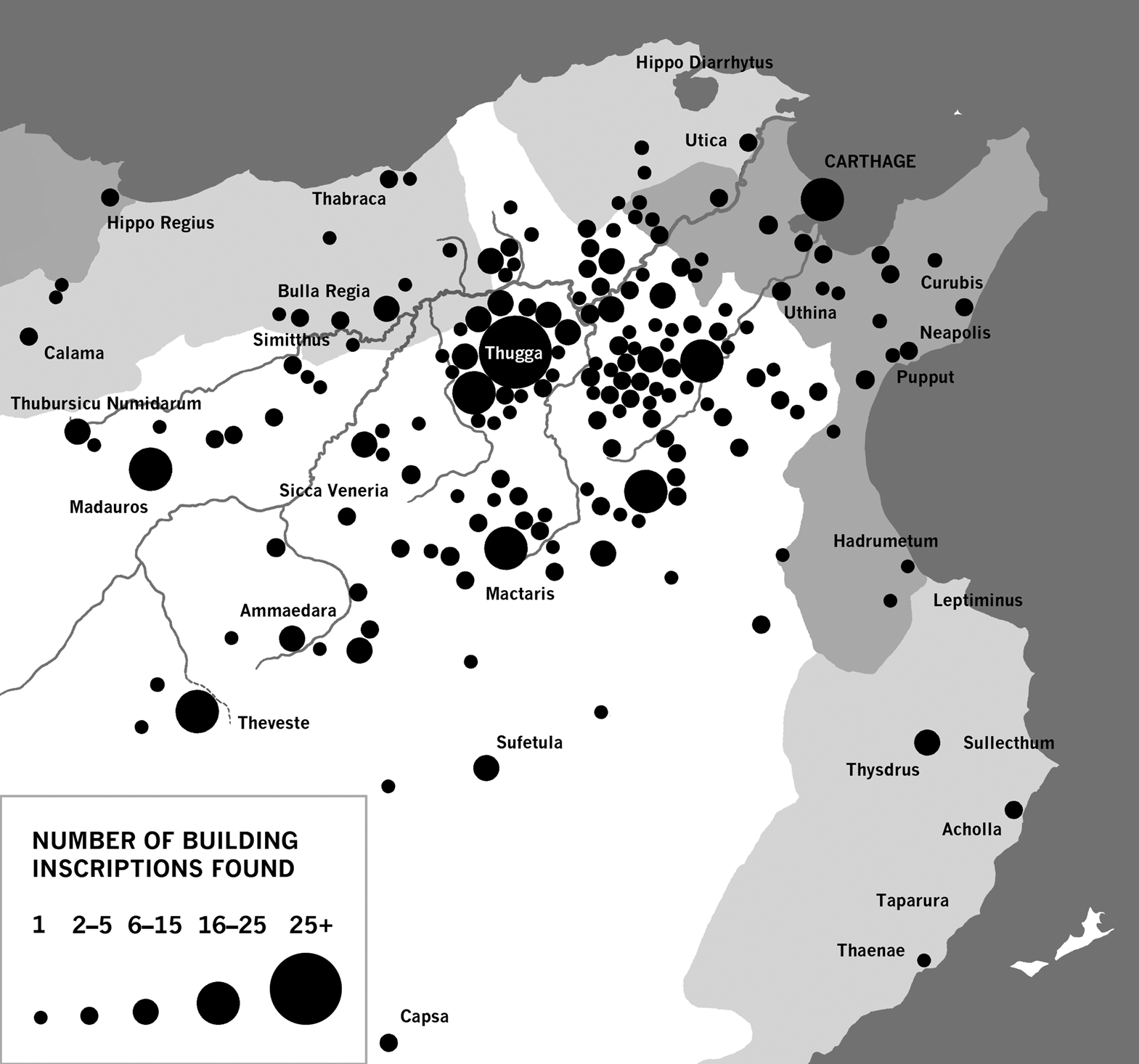

To demonstrate this, it is necessary to explore how building inscriptions are distributed over the area, and what has determined their survival. Their spread (Fig. 4) does not correspond to the demography of the area, which can be misleading. Later habitation has resulted in very few texts surviving from the entire littoral, which was densely populated in Antiquity and remains so today. For example, the peninsula of Cap Bon and the coastal region to its south known as the Byzacium (also known as the Sahel) are almost devoid of building inscriptions from any period, but surveys have revealed them to have been densely settled.Footnote 40 Survival is thus capricious, and stray finds can reveal otherwise unknown municipalities and even colonies, complete with fully developed honorific practices.Footnote 41

FIG. 4. Findspots for building inscriptions. The areas marked in grey are the most densely populated modern governorates and wilayas. (Source: Institut National de la Statistique, Tunisia; Office National des Statistiques, Algeria). They were the most populous also in Antiquity, especially the towns along the coast, which is not reflected in the number of finds: Hippo Regius 3 texts, Thabraca 4, Hippo Diarrhytus 0, Utica 3, Carthage 25, Carpis 2, Clupea 0, Curubis 4, Neapolis 0, Pupput 0, Hadrumetum 1, Leptiminus 0, Sullecthum 0, Acholla 2, Taparura 0, Thaenae 1. Also under-represented is the colony of Sicca Veneria, modern Le Kef.

The same problems occur in the major ancient cities of the region. Bar Carthage, not one of the many coastal towns from Hippo Regius to Thaenae (including important cities such as Curubis and Hadrumetum) has produced more than four building inscriptions, and many have produced none. Large inland towns are not much better evidenced, such as the colonies of Utica (three texts), Uthina (two doubtful fragments), Thysdrus (six) and Sicca Veneria (six). Among features qualifying a town as ‘major’ are the status of colonia, a large urban territory (as recently revealed for Simitthus, with four texts)Footnote 42 and the presence of imperial bureaus (as for instance at Carthage, Hippo Regius (three), Hadrumetum (one) and Thysdrus).Footnote 43 All the African colonies listed by Pliny the Elder (NH 5.22, 24, 29–30) are virtually devoid of building inscriptions. Another reflection of the significance of African towns is the number of recruits in the African legion that were drawn from them, a method used by the excavators of Uthina to highlight the importance of this city.Footnote 44 By far the most soldiers came from cities that are ‘silent’: in ascending order Uthina, the colony of Maxula (no building inscriptions), Simitthus, Sicca Veneria, Utica and, not surprisingly with the largest number of recruits, Carthage.

Carthage is the most critically under-represented of all cities in the area, and is therefore often neglected in epigraphic studies. It is worth remembering that Carthage counted as one of the ‘big four’ cities of the Empire, and that its population numbered in the hundreds of thousands.Footnote 45 Its territory covered a significant portion of my study area (including the majority of its minor towns), and its influence stretched far beyond it. Carthage has the largest record of building inscriptions of all major cities (twenty-five), but is easily exceeded by its own dependent Thugga, with seventy-four. This is more than the whole littoral has produced from Hippo Diarrhytus in the north to Thaenae in the south, including Carthage, Thysdrus and all other cities. This leads to the second factor affecting the distribution of building inscriptions in the area: excavation and publication. Turn of the century ‘total excavations’ (of a kind no longer considered sound archaeological practice) generated disproportionately large samples from certain towns, especially Thugga but also, for instance, Musti and Thubursicu Numidarum.Footnote 46 This should not be taken to reflect their size or importance. Even many non-excavated inland villages have larger records than most coastal cities.

Taken together, later habitation and excavation seriously distort the image of construction in the region: a record that practically excludes the most populous areas and all major cities cannot be anywhere near representative. Only twelve items in total have survived from the entire Sahel, and half of them from Thysdrus, which does not suffice for any large-scale generalisations on the fate of its cities. However, there is also a third, and less often acknowledged, factor that affects how building inscriptions may be analysed: they were not produced equally in all places. On the one hand, some rural areas that show up empty on maps registering inscriptions (such as the one above) were home to agricultural estates, of which many had villages that could compete with formally recognised towns in size and monumentality.Footnote 47 This is not adequately reflected in epigraphy, which appears to have been a medium for towns. It is worth noting that the few building inscriptions from estate villages imitate those of towns, with coloni posing in a manner similar to councils and magistrates.Footnote 48 The emergence of many rural episcopal sees in the fourth century is instructive: these ‘empty’ areas comprised both people and resources, but not the political institutions that generated inscriptions.Footnote 49

On the other hand, and importantly for the present purposes, all towns did not produce inscriptions to the same extent. Some of the most notable towns in the area have yielded fewer items than they ought to, considering their state of preservation and excavation. For instance, Hippo Regius has left a well preserved monumental core, but only three building inscriptions. The colony of Uthina is one of the best preserved, examined and published sites in Tunisia and has seen very little post-Roman habitation, but has produced only two fragments, both of which may come from statues.Footnote 50 Curubis has preserved other honorific inscriptions from several centuries, and it seems unlikely that nothing was built there during the entire imperial period. Similarly, plenty of inscriptions survive from Sicca Veneria and Thysdrus, but very few building inscriptions. Again, the most conspicuous case is Carthage. As the many volumes of the CIL from the city of Rome show, continuous habitation does not preclude the survival of inscriptions. Carthage returns four times as many inscriptions overall than Thugga in a cursory online database search (8,000+), but only one-third as many building inscriptions.Footnote 51

Furthermore, when treating the records from major towns on the coast separately, it becomes clear that they are different from those inland in terms both of buildings and chronology. In spite of being smaller, the records from the coastal towns are more diverse: their share of inscriptions from secular buildings is much larger than their share of the sample overall. Conversely, they are less dominated by sacra. There are certainly shrines on the coast — around 50 per cent of the coastal texts record sacra — but this is significantly lower than inland (where many towns have no other record at all), and no arch has been epigraphically attested in a coastal town. This has been obscured by treating the slim record from the littoral together with the mass of inland inscriptions.

Moreover, building inscriptions from the coast show no tendency to accumulate in the late second century, but appear to spread evenly over the three centuries studied here. For example, the texts from Hippo Regius record the paving of a forum in the Flavian period, an aedicula dedicated to Hadrian and a bath restoration under Septimius Severus, while all four texts from Curubis (recording a hospitium, city walls, a horologium, a pluteus, two scholae and a road) date to the first century b.c.Footnote 52 All inscriptions recording roadworks come from coastal towns and neither of them date to the Antonine-Severan period.Footnote 53 Three of them come from Carthage, where inscriptions from a wide range of buildings have survived, none of which dates to the reigns of Severus or Caracalla. To conclude, it appears that the coastal cities did not participate in the abundant Antonine-Severan commemoration of sacra. To understand what generated it, one must look to the communities where such inscriptions were actually produced, and consider who was responsible for them.

V BUILDERS AND THEIR BUILDINGS

It comes as no surprise that the same division is also evident for those who constructed the buildings: the records from smaller towns are dominated by two well defined, and closely related, categories of builders, while major cities (and especially the coastal towns) see a greater variety. To classify the patrons presents challenges; not only are many texts damaged, which (as for buildings) excludes about one-third of the sample, but the varied phraseology of inscriptions from the area (as explored by Ari Saastamoinen) makes for very different registers of detail. Some towns favoured long texts; in others, nothing about the builders was disclosed beyond their names. In yet others, only construction by town councils was recorded, which should not be taken as an indication that no individual ever built there.Footnote 54 In many cases, it has not been possible to establish the status of a builder or their relation to the community in which the project was undertaken. Nonetheless, the picture is clear: the vast majority was produced by the leading officeholders of the towns, either individually, which is the most common, or collectively as town councils. The inscriptions quoted in Section II above are typical examples, but there are many variants.

About one-third of all agents attested in the sample (insofar as the texts permit identification) are town councils and two-thirds individuals, of whom about 70 per cent are local officeholders.Footnote 55 Of these, more than 90 per cent (155 instances) hold priestly office, and most of them an imperial priesthood, for the most part the flaminate. The exact position is unclear for several of the remaining 10 per cent, and they may well have been flamines or flaminicae too. There is little resemblance to Zuiderhoek's sample from Asia Minor, in which the two most impactful agents were elite benefactors (whom he defines as distinct from ‘civic benefactors’) and, especially, dēmoi. Footnote 56 As Ari Saastamoinen observes, the populus had no role in posting building inscriptions in Roman North Africa,Footnote 57 nor is the community addressed as a beneficiary. Moreover, while Zuiderhoek's elite benefactors and dēmoi were responsible for all types of buildings, in North Africa almost all officeholders, and very nearly all councils, built shrines and arches.

We thus cannot argue that the councils filled the gaps left by the officeholders. Town councils did occasionally build and inscribe secular buildings, but this should not be overstated: there are eight examples in a sample of 103, while all remaining texts that mention the building itself come from sacra, and most that omit the building are known to belong to arches.Footnote 58 Furthermore, texts that exclude the patron were plausibly posted by town councils, and these inscriptions almost exclusively commemorate sacra.Footnote 59 Both categories are mainly attested inland, and only one project by a council is attested on the coast.Footnote 60 The first priests appear in the Julio-Claudian period and the councils under the Flavians, but their numbers remain small until the mid second century when they begin rising sharply, only to decrease as sharply in accordance with the drop in numbers of the sample as a whole. The councils continue to appear as builders throughout the third century, if in lower numbers, while the flamines drop away more noticeably.

It is quite clearly the inscriptions by honorary priests and town councils that create the distinct pattern of the epigraphic record from the area. Other types of builders appear more rarely, and many only once. They do not favour sacra, nor accumulate in the late Antonine–early Severan period, and a significant share is contributed by locations otherwise lacking in building inscriptions. In other parts of Roman North Africa, emperors, governors and legates are frequently attested in the role of builder, but in this area such texts are very few. The latest work of an emperor to be inscribed (before Diocletian) is by Hadrian, and such works are limited to aqueducts in major cities (Carthage and Thysdrus) or bridges in towns associated with the military and/or the res priuata (Vaga, Ammaedara and Simitthus).Footnote 61 The area may have become of less concern when it became civil, and few emperors ever visited. Only one project is known by a legate of the III Augusta, an unknown object at Theveste under Domitian (when the legion was moved there).Footnote 62 An aqueduct at Ammaedara by the proconsular legate in the reign of Marcus Aurelius is also unique.Footnote 63 Surprisingly, only three projects by proconsuls are attested before Diocletian (at Carthage under Claudius, Hippo Regius under Vespasian and Thuburbo Maius under Commodus), even though part of their duties was to monitor construction in towns under their rule.Footnote 64 In contrast to locations such as Lepcis Magna in Tripolitania or Lambaesis in Numidia (where the legion was moved), imperial influence over urban architecture in the study area — as far as epigraphy is a guide — was exerted mainly through regulation and permission. The small number of building inscriptions by more junior imperial functionaries does not change this picture.Footnote 65

Beside the priests, inscriptions posted by members of the local elite are few and varied. Aediles are attested in six texts, featuring mainly secular works and dating to the reigns of Augustus, Alexander Severus and Diocletian.Footnote 66 This is a remarkably low count considering the tasks associated with this office. Also surprisingly few are inscriptions attributable to the most exclusive members of the African elite, or the ‘African oligarchy’, as Mireille Corbier once styled it.Footnote 67 This consisted of a small group of very wealthy families who dominated this part of Roman North Africa socially, economically and politically. Their influence and networks spanned the region, including properties and patronage in several of its towns. Although some families may have originated from these communities, their main residences were on the coast, and particularly at Carthage where they held offices and priesthoods.Footnote 68 In the second century, the orator and philosopher Apuleius hailed them in flowery phrases, and the Christian apologist Tertullian mocked them for their complacent wealth and elegance.Footnote 69 Even so, members of this regional elite are rarely attested in building inscriptions, and when they are it is usually in association with secular buildings.Footnote 70

Six inscriptions by patrons have been attested at Thugga but the latest dates to the reign of Hadrian, while the pair of African liberti responsible for three texts in the same town were active in the Julio-Claudian period.Footnote 71 Few other social categories of builders are attested more than twice, and many are known from only a single text, such as a senator constructing baths at Carpis.Footnote 72 Most of these are found on the coast and especially in Carthage, including an imperial freedman who restored quays and banks,Footnote 73 a leatherworker who raised a public horreumFootnote 74 and the enigmatic Deborosi (variously interpreted as an ethnic label, a group of legionaries or a confraternity) responsible for a roadside wall.Footnote 75 Granted, Carthage has produced the largest coastal record, but a similar image emerges from the comparatively good record from Hippo Regius where none of the builders were priests, imperial or otherwise.

The impression gained from the previous sections is thus repeated for agency: testimonies of one kind dominate the record of minor inland towns, while the coastal towns show more diversity. The building inscriptions associated with the miscellany of builders other than priests or councils are too few to have an impact on the corpus overall, but when they are examined separately three things become clear. First, they do not become more plentiful in the second century. Second, most of them — at either end of the social spectrum — are attested in cities and areas with low counts of building inscriptions. Third, the buildings involved are for the most part secular. In fact, together they account for the majority of secular buildings in the whole sample. The pace of their activities should not be assessed based on the chronology of sacra built by priests and councils in minor towns in Carthage's hinterland.

We may perhaps gain a more accurate impression of construction in the area if we removed shrines and arches from our sample altogether. As few as they are, secular buildings correspond better with the area's urban hierarchy, and their more even timeline (excluding Diocletian's reign) suggests that maintenance of the cities may not, after all, have changed so much over time. There are several sub-samples that merit attention, including the involvement (or its opposite) by emperors, but also that of aediles, who were no doubt responsible for a larger share of the area's urban architecture than their few inscriptions suggest. The same is arguably the case for the regional African elite. What seems clear is that the corpus of inscriptions from the area is made up, on the one hand, by a small but continuous trickle of testimonies to a wide array of buildings by as varied a group of builders, on the other by a much larger category of inscriptions from sacra constructed by officeholders and councils in small towns, a category which increases remarkably during the second century. It is, in short, the texts from sacra that represent the anomaly, and which require explanation.

VI THE SOCIO-POLITICAL CONTEXT FOR SACRA AND SECULAR BUILDINGS

The last factor to be analysed is how the building inscriptions relate to the towns and their socio-political structures. The inscriptions represent a spectrum, from projects conceived in close relation to the town councils to those that at least appear to be independent of them. It should be noted that the activities of priests and local councils belong to the same social stratum, and that they were closely intermingled. The projects of the priests were tied to positions granted by the councils, and were, in a sense, partly funded by them, while the councils’ decisions were influenced by their most prominent members — that is, the priests. This close interconnection explains the similarity of their building activity, and contributed to making the building projects of the priests epigraphically visible.

I use ‘council’ or ‘senate’ as terms denoting administrative bodies equivalent to an ordo, but far from all towns in the area had legal rights. Many were dependent on others, especially in the territory of Carthage. This administrative territory, which is known to historians working on Roman North Africa as the pertica, comprised scores of dependent towns.Footnote 76 Most of them were ciuitates, which in this region denotes a subordinate, native town rather than a municipium. Their status is hard to define, not least because many of them had developed political institutions that approximated those of independent towns. Jacques Gascou called them ‘proto-municipalities’, or ‘municipia-to-be’.Footnote 77 Alongside them were enclaves of Carthaginian citizens known as pagi and which formed part of the Carthaginian pertica, with Carthage as their patria. Footnote 78 The pagi were not spatial but administrative units; an outlying pagus could co-habit with a dependent ciuitas, forming ‘double towns’ such as Thugga or Uchi Maius.Footnote 79 All these entities had their respective institutions, and dependent towns could style themselves respublicae (as Uchi Maius does in the inscription above) and raise capitolia as though they held legal rights.Footnote 80

One trait these townships had in common, regardless of legal status, is that they built sacra, and that they appointed flamines or sacerdotes who did the same. These versatile priesthoods provided a unifying element to the wide array of urban communities. They could be held by both men and women, and were appointed locally by the (variants of) councils in place without, as far as is known, restrictions or compulsions from above. They appear in several varieties from the local annual or perpetual flaminate (the version featured in most building inscriptions) to the provincial priesthood.Footnote 81 It is doubtful that these constituted an internal hierarchy. As James Rives points out, the flaminates should be viewed in relation to the local cursus honorum.Footnote 82 Held after its completion, they may even have been devoid of functions, serving only as marks of distinction.Footnote 83

What is clear is that they represented the pinnacle of local society. The inscriptions might give the impression that the councils and the priests (who had passed through the council's ranks) were alone in influencing the public sphere. But, as Christopher Dawson has shown, the populus also had an important role, including initiating honours, collecting money to fund them and putting pressure on local senates through curiae.Footnote 84 The curiae were associations that cut across social classes and had their own fees, ceremonies and magistrates, testifying to the many layers of local civic life. However, in the types of building inscriptions that characterise this region, only a small, privileged fraction of the political life of its towns is visible.

In fact, the priests’ building inscriptions seem to mark the precise moment of achieving priestly office. Most of them describe their building projects as undertaken ‘for the sake of office’, ob honorem (or versions thereof), a practice that is characteristic of African epigraphy. The inscription from Musti (quoted in Section II above) is but one of many such texts, which typically recount earlier offices held and the fee paid to the local treasury for the current office (the priesthood) together with the cost of the building project, as well as various close relations who are often also promoted to office. The practice is attested in about half of all (reasonably legible) African building inscriptions,Footnote 85 but many fragments show characteristic elements, and the proportion is certainly higher in the hinterland of Carthage.Footnote 86 The practice of building ob honorem is attested in the case of both temples and arches, and accounts for almost all imperial statues raised by individuals, in sharp contrast to other provinces.Footnote 87

Whether the fee (or summa honoraria) helped fund the building project or not is a much debated issue.Footnote 88 I am inclined to think that it often did. This is at times explicit, as in the case of works undertaken ex summa honoris, ‘out of the fee for office’.Footnote 89 An undated text states that ‘…the temple which C. Clodius Saturninus promised to construct and complete from its foundations for twice the fee for his and his brother Clodius Celer's decurionates, his niece Clodia Macrina, daughter of Caius, built from its foundations with 12,000 sesterces, having added, beyond the 6,400 sesterces fee required for his office, 5,600 more out of her own generosity…’.Footnote 90 To fund dedication festivities for someone else's building could also serve the same purpose. For example, a private man paid ex summa flamoni perpetui for the dedication of a civic project, occasioned by the elevation of Thugga to the status of a colonia, not his own progression.Footnote 91 The texts often foreground the fees, by giving the cost of the whole project in multiples of it, or simply as ‘more’. Payment details do not generally come with the most costly projects, as Jacob Munk Højte observes, and should not be interpreted as boasting.Footnote 92 The hypothesis that ob honorem originally represented ‘pure’ benefactions, but in time came to represent taxes, is attractive but hard to prove, since the formalisation of the process appears to be what motivated the texts.Footnote 93 The buildings receive little mention, and sometimes none at all.

In either case, there was a strong expectation that the recipient of the highest honours should build sacra. Only four inscriptions from secular buildings record that these were raised ob honorem, and all but one dates outside the ‘peak’ decades.Footnote 94 The exception is an Antonine theatre at Thugga, which was likely raised for a flaminate in Carthage rather than the local town.Footnote 95 The same pattern emerges from the rest of Roman North Africa, where only two instances of ob honorem construction (of more than 150) involve secular buildings, and both date to the late fourth century. Where the study area differs is in scale: there are more ob honorem testimonies, and the office in question is more often the flaminate, while elsewhere it is usually the duumvirate. Only four duumvirs are attested as builders in the study area, and three of them also hold priesthoods which is likely the office commemorated. More minor projects such as statues of gods and emperors could be raised for duumvirates, aedilitates and decurionates (which sometimes appears to have been a systematic arrangement), but shrines and arches were reserved for the highest local positions.Footnote 96 In this area, these were honorary priesthoods.

It seems clear that the priests did not build by virtue of specific religious responsibilities, but in their generic capacity as holders of high office. The priesthoods rarely correspond to the sanctuaries built, and there appears to have been no expectation that a flamen of an emperor should raise an imperial shrine. Their inscriptions contain very few phrases of devotion such as ex uoto or ex iussu diuinitatis, which invariably appear in exceptional contexts.Footnote 97 The texts are preoccupied with money, careers and families, often painstakingly itemising payments across generations. This should not be interpreted as a lack of piety on the part of the builders, but highlights that building inscriptions were not the medium of choice for expressing such sentiments.Footnote 98 The purpose of the texts was to document local progression, through an intimate connection between the political hierarchies of the towns and their religious monumental framework. As a result, sacra made these hierarchies visible — literally enshrined — in the public spaces of the towns.

Most secular buildings in the sample were generated through other processes, and their texts also differ from those of civic and priestly ones. Inscriptions dating to the first three centuries a.d. were generally sparing of technical detail and are consequently hard to date, which has often excluded them from discussions of construction in the area. As an example, several projects by members of the Arnensis tribe of Carthage state only their names.Footnote 99 One of few datable texts is an inscription from an unknown building at Uchi Maius:

Sex. Pullaienus Florus Caeci[lianus s(ua) p(ecunia) fecit?] | et Uchitanis Maioribus dono [dedit]

Sextus Pullaienus Florus Caeci[lianus raised (it) out of his own money] and [gave] it as a gift to the people of Uchi Maius.Footnote 100

Florus came from a well established elite African family with properties and patronships in multiple towns, and he himself held high positions in Carthage under Hadrian.Footnote 101 This is not mentioned in this inscription, however, but on a statue base found in a different town. What the brief and damaged text nonetheless does convey is that the building was a gift to the people of Uchi Maius; whatever it was, it was presented as a benefaction to the community, not a step in Florus’ career. The lack of a dedicatory formula makes it unlikely that it was a shrine or an arch.

A similar pattern has been observed by Christopher Dawson for statues. Statues to locals included minute details on their families and careers, but those to external honorands occasioned few words, even though they were of higher status.Footnote 102 Dawson suggested on the one hand that honours to locals required more justification (hence more details), and on the other, that builders from outside the community used fewer words because they were less emotionally engaged.Footnote 103 However, building inscriptions by locals are not usually emotive. Brief as it is, Florus’ text expresses more sentiment than most of them. A more convincing explanation for a similar phenomenon in Italy has been offered by Werner Eck, who observes that reticence made the individual come across as more distinguished.Footnote 104 I would go further and suggest that these details were irrelevant for the context. Inscriptions by locals documented transactions within locally defined honour systems, channelled through local political bodies. When only Florus’ name is given, this is not because he or the townsfolk did not care about his gifts, but because his career had long since progressed beyond his local cursus honorum (which was likely not completed in Uchi Maius in any case).

The same pattern in terms of social class, building activity and epigraphic presentation is observable in yet another sphere: inscriptions on statue bases that mention construction. These fall neatly into two categories: one that lists construction in the cursus honorum among the honorand's past achievements and a second that presents a building project as the direct reason for the statue honour. The first group conforms well to the texts by local magistrates: the works are almost exclusively sacra, and those that can be dated belong in the reigns of Commodus and Septimius Severus.Footnote 105 Statues raised in gratitude for a building, by contrast, honour individuals of higher than local standing, including a Carthaginian, three senators, two high-ranking equestrians and at least four civic patrons.Footnote 106 Their projects read like an inventory of structures ‘missing’ from the record of building inscriptions: three amphitheatres, two theatres, two baths, one aqueduct, one hydraulic structure (bath, aqueduct or fountain), one portico and one reconstruction of the entire forum area, including a curia and a capitolium (which is the only sanctuary in the sample).Footnote 107 They are spread fairly evenly from the reign of Hadrian to the late third century, and some appear in locations where building inscriptions are rare (Uthina, Curubis) or non-existent (Pupput).

It is, thus, not the case that the priests were the only individuals who built, or even that their sacra stood the highest in local favour. The different types of mediation associated with different projects and elite registers have less to do with emotional engagement than with the relation of the projects to local political institutions. The social mechanisms that they embody are different: the inscriptions of the priests detail transactions between councils and their leading members, while those of the higher, regional elite reflect a more vertical exchange between benefactor and community. They also elicited different responses: there are no statues raised in honour of the flamines in gratitude for their temples, while building inscriptions are less common for the projects of the higher elite.Footnote 108 It is not impossible that these were broadcast through non-permanent media such as bronze, but if so, these texts have not survived.Footnote 109

This lack of epigraphic documentation should not be interpreted as lack of building activity. The meagre record of building inscriptions by members of the regional elite has been taken to indicate that they had little interest in these small towns and concentrated their efforts on Carthage. This would accord with the situation observed by Zuiderhoek in Asia Minor, where the wealthiest, regional elites appear to have had a limited role in sustaining (local) urban life. But if one considers overall how few African texts mention secular building, this thin record is cast in a different light. Moreover, their projects tend to be very costly, far beyond the level of their local counterparts. The fact that few statue bases commemorate construction should not be taken to indicate that such projects were rare; as Claude Lepelley observes, most statue base inscriptions state the reason for the honour as ‘generosity’, without specifying how it was exercised, and several of these may refer to construction.Footnote 110 Moreover, such texts become increasingly vague with time, disclosing fewer concrete details.

In any case, we cannot exclude the possibility that the regional elite was responsible for a substantial share of the amenities in local towns, especially given the lack of other claimants to them. The same is the case for aediles, whose inscriptions resemble those by high-status benefactors more than those by the priests. They make no reference to fees, careers or families, and at least one was posted on demand by the populus. Furthermore, their projects are presented as undertaken in the course of office, not to obtain it.Footnote 111 The glimpse of benefactions that the statue bases provide warns against using inscriptions from sacra to assess their rates more generally: ob honorem constructions were not the only, or even the most important, channel through which euergetism was practised.Footnote 112

VII EXPLAINING THE RISE AND FALL: PEER-TO-PEER COMPETITION AND THE IMPACT OF CARTHAGE

Analysing building inscriptions from this area thus requires a great deal of caution. For one thing, the corpus is too skewed to allow us to chart architectural development. This must be the task of archaeology, independent of epigraphy. Perhaps the most misleading aspect of the inscriptions is their abundance. This makes them appear representative of construction in the area, even though they only cover certain types of building activity. The missing pieces are important ones, involving the largest and most expensive buildings, the most populous and prominent cities and regions and the highest status builders. Importantly, we must not fill these gaps with more of what we have, which would mean reconstructing the situation in the larger cities from the smaller, and assimilating the chronology of all types of buildings to that of sacra. What we do have, and in abundance, are structures dedicated to an emperor or god by leading small-town elites in the Carthaginian hinterland, in association with obtaining the most prestigious local positions. These testimonies accumulate in the second century and plummet suddenly in the early third, never to regain the same frequency. There is little to suggest that this pattern is relevant for projects that involve other buildings or builders.

This leads to the more difficult question of what caused this pattern. Something did change, but it is unlikely to have been prosperity. Large cities were not affected, nor were amenities. This has ramifications also for arguments based on the communities’ needs:Footnote 113 the structures that appear and disappear in the record represent neither utility nor entertainment. Arguments regarding changing modes of self-representation accord better with the data,Footnote 114 but they have not recognised the specific projects involved. Moreover, they do not sufficiently explain the slow rise and sudden fall in numbers of inscriptions, or their precise timing. Why should such changes affect construction by local priests, but not by external benefactors? Why in dependent inland towns, and not in colonies on the coast? More plausible is the suggestion by Christophe Hugoniot that peer-to-peer competition had escalated to the point of harming the communities, and was duly curbed from above.Footnote 115 However, the changing frequencies do not extend to secular buildings, which arguably had the strongest impact on the welfare of the towns. His explanation also leaves the question of geography unanswered.

The most fruitful line of inquiry lies in the centrality of sacra to African political life. The question arises whether changes in epigraphic commemoration were caused by changes in religious practice. This makes sense for the dearth of building inscriptions under Constantine, when it is likely that raising and inscribing shrines became less appealing. There are plentiful donations to churches, but these were not channelled through civic institutions in comparable ways, and thus did not generate stone inscriptions. This does not mean that these institutions were in decline. Flamines were still appointed in the Vandal period, but they no longer inscribed sacra on advancement.Footnote 116

The decrease in inscriptions in the early third century is less easily explained with religious changes. James Rives tied it to the gradual erosion of traditional public cults in the imperial period, but if so, why are inscriptions from sacra so few under the first century and a half of imperial occupation, but rise to a peak when they should, on this model, be petering out?Footnote 117 The fall in numbers is also too sudden to be explained by long-term cultural developments. However, if we shift the focus from the buildings themselves to the processes that generated them, this allows us to reframe the questions: why were honorary priesthoods so sought after in this time and place, and why did they cease to be so?

Using religious architecture for social positioning is not unique to Africa. The inscriptions in the temple at Baalbek come to mind, or the competition for neokorates in the Greek East, even to the point of petitioning the emperor to reject the bids of rivals.Footnote 118 The African inscriptions warn against treating this as an ‘Eastern’ phenomenon. Shrines were raised competitively, and not just capitolia (as observed by Josephine Crawley Quinn and Andrew Wilson)Footnote 119 but also high profile dedications to the genius deities of the towns, as well as Saturn and Caelestis. Arches emphasise townhood, by solemnifying urban nodes, and by making the urban territory manifest as gates in imaginary city walls. Like statues of emperors they were necessary urban trappings, and this is also the case for imperial priesthoods: the greater the town, the more flamines it appointed. A city as grand as Carthage could sport specific flaminates to a range of diui, while small towns only had generic ones, nudi dicti.Footnote 120

Where Africa differs is in the way ob honorem procedures allowed individuals and families to exploit this shared monumental framework for their own progression. It was up to the councils to decide how many of their members to appoint to flaminates (and whether to accept their sacra as covering the fees for these), no doubt based on the availability of candidates and their interest in pursuing the position. For a few decades this interest appears to have been high: spouses, siblings and children often gained the office at the same time, and eventually every member of an ambitious family would have been a flamen for life. This begs the question why this was so much more common in the study area than in the rest of Africa, and in the smaller towns rather than the larger. The positions were expensive, and not mandatory for completing a cursus honorum.

The answer may lie in the further aims of their holders: a priesthood represented the top of the local pyramid, but also the starting point for another, regionally defined competition against peers in neighbouring towns. Three factors contributed to raising the stakes for such competition in this area. The first is the interconnectivity of its towns, which allowed a career to begin in one and continue in another. Several overlapping hierarchies helped increase cross-regional social mobility, including the imperial res priuata and the systems of dependency that integrated subordinate towns both vertically with the metropolis and horizontally with each other. The second contributing factor is the extreme density of urban settlement. This made for an abundance of rivals as well as narrower windows of advancement. Ambitious elites were prompted to seek further distinction to set themselves apart. The third factor is the presence of goals that made such efforts worthwhile. Unique to this area is the proximity of the ‘mega-city’ of Carthage, and particularly the realistic prospect for the uppermost stratum of local elites of a career there. This prospect (as we will see) accords well with the chronology, geography and focus of the inscriptions from sacra.

The statue record reveals several prospects open to Africans, including adlection to the Senate, equestrian posts abroad, procuratorships and the provincial priesthood. However, these attestations skirt the area where building inscriptions accumulate under the Antonines, coming from locations that have produced few such texts, such as Sicca Veneria where a procurator instituted a foundation for boys and girls,Footnote 121 or Thysdrus where a citizen became flamen of Augustus after a splendid imperial career.Footnote 122 African senators were drawn from the leading stratum of colonies such as Utica, Carthage or (particularly) Bulla Regia and its neighbours in the north-west, and not from the social class dominating the building inscriptions.Footnote 123 The same geography applies to officials in the res priuata, such as T. Flavius Macer who, after capping his cursus with a flaminate in Ammaedara, continued to procuratorial posts and was honoured at Calama and Hippo Regius by both citizens and subordinates in the res priuata.Footnote 124 Municipal and imperial hierarchies were intertwined, and a career could span considerable distances. For example, a scion of the Iulii Sabini from Madauros served as procurator in Leptiminus in the Sahel,Footnote 125 and another procurator of regio Leptiminensis received honours in Theveste from the Tripolitanian towns Oea and Sabratha.Footnote 126 Even more prestigious was the African priesthood. Sacerdotes Africae received honours in their home towns, proudly emphasising that they had completed their cursus there,Footnote 127 but the locations (such as Bulla Regia or Simitthus, whose sacerdos had advanced through the res priuata)Footnote 128 invariably lay outside the Carthaginian territory.

Moreover, these prospects are not exclusive to this part of Africa, and cannot explain its idiosyncratic behaviour. What truly did set it apart was Carthage, which was home to the wealthiest elites and the most prestigious civic institutions in Africa, as well as all levels of the imperial administration. For the social class captured in the building inscriptions, Carthage was the model to be emulated and the goal to be pursued, in ways felt far beyond its territory. Lesser colonies could also inspire honorific practices; for example, the small town Thubba honoured an eques at Utica, and the decurions of Sicca Veneria made dedications in the city's pagi.Footnote 129 However, Carthage operated on a different level, and the influence of the city and its elites was felt across the region. For example, the town of Segermes on the High Tell honoured a Carthaginian at Capsa far to the south, and a colony as important as Ammaedara set up honours in Carthage, even though it lay at a considerable distance from this city and had never been dependent on it.Footnote 130 Carthaginians are frequent among the benefactors in the area, attested both in building inscriptions and as recipients of statue honours.

This tendency is strongest within Carthage's own territory, where the presence of the city significantly broadened the social and political prospects of local elites. The metropolis’ wealthiest families represented a ‘superstratum’ above the class visible in the building inscriptions, and the city's institutions had more subtle gradations. Its priesthood of Ceres (once held by Sextus Pullaienus Florus) was highly esteemed, but even a mere decurionate in Carthage ranked far above a small-town flaminate, and was prohibitively expensive for most Africans.Footnote 131 However, for the one per cent, Carthage's political hierarchy was permeable, and membership brought not only prestige but power. The Carthaginian ordo was the highest decision-making body in Africa (beside the proconsul) and controlled a vast, populous and very wealthy area — precisely the area where elite locals posted inscriptions that showed them to be eligible. Christophe Hugoniot underscores the prestige that progression to Carthage brought to small-town elite families.Footnote 132 It required completing a local cursus with all its attendant costs, and few could have contemplated such a ‘double career’. The process was thus self-selective, extracting the richest Africans from across the region. Candidates are known from as far as Cuicul in Numidia, but the majority are attested within the pertica of Carthage. The Pullaieni may once have gained their position in this manner, while the Marcii were more recent arrivals.

The geography of ambition is thus divided, with progression to Carthage attested within its territory, and progression to other goals attested outside. It is possible that towns in the pertica had institutional links that facilitated advancement to Carthage. Conversely, elites in such towns may have been constrained to climb through the metropolitan ranks. Much remains to be understood about the social organisation of pertica towns, but it is in any case clear that Carthage informed it. As Monique Dondin-Payre has remarked, of the many variants of citizenship involved — including local, Roman and Carthaginian — the Carthaginian was likely the most prestigious from the local point of view.Footnote 133 Locals who took office in Carthage transferred into the Arnensis tribe of Carthage; for instance, the Marcii brothers held flaminates at Carthage and were members of the Arnensis, but their father remained in the local Quirina.Footnote 134 At Segermes, a man transferred to the Arnensis from the Papiria,Footnote 135 and in Thugga a couple belonging to the Quirina made much of their son who became flamen in Carthage and joined the Arnensis. Footnote 136 This suggests that these men were not fully Carthaginian before. Mandatory or not, their new Arnensis affiliation clearly announced their elevated status, which may be a reason why the use of tribus lingered so long in this area.

Carthage would have loomed large for such aspirational elites, who would have been acutely aware of its leading families. They would also have been well placed to find patrons to support their enrolment into Carthaginian pagi and curiae, and they were no doubt approached for this purpose themselves if successful. The pool of candidates corresponds exactly to the group which posted so many building inscriptions in the late second century, inscriptions that testify to the completion of all requirements, with public confirmation (and some extra besides) to recommend them. These honorary priesthoods are in themselves testimonies to aspiration; distinctions made all the more attractive by the desirability, attainability, yet exclusivity, of Carthage's political institutions. In this area, nothing less would suffice: the number of available positions was limited, but the competitors plentiful.

Moreover, the flaminate could promote whole families, as amply attested. This makes little sense for elites angling for imperial positions. For instance, women — young and old — are frequent among the builders in the role of flaminicae, but they could not hold procuratorships (vel sim.). However, elite women had central roles in kin networks. The end goal of the broad promotion of families observable in the building inscriptions was surely to become established within the higher regional elite. Henrik Mouritsen's observations regarding the Italian regional elite is here of interest: it was under constant renegotiation, with unstable dynasties that made for continuous competition for inclusion.Footnote 137 Key to gaining a foothold were formal positions in the metropolis, which for the domi nobiles was Rome, but for elites in this area was Carthage. Their power also rested on kin networks, amicitia and patronage, but Carthaginian offices were a sine qua non, and served as entry points.

Ambitions inspired by Carthage fit both the geography and social context of the building inscriptions, as well as their double focus on formal progression and kin. The density of towns ensured a steady flow of applicants, the integration of towns under the canopy of Carthage placed them in competition and the monumental visibility of successful candidates goaded them further. For these aspirations, sacra served as both a vehicle and a stage. The absence of testimonies in the largest and wealthiest cities reflects the higher standing of their leading families, who were long-standing members of the regional elite. Other ‘silent’ towns may have lacked the institutional links to Carthage that guided (and aided?) the aims of elites in the pertica. Exceptions exist, such as the colony of Musti which was dominated by Carthage and behaves epigraphically much like its dependent neighbours, but on balance this pattern holds up well. It remains a hypothesis, but it does accord with the data.

VIII THE END OF THE AFFAIR

The pattern suggested above also offers an explanation to the disappearance of inscriptions. Sometime in the early third century, the ordo of Carthage demonstrably ceased to admit outsiders. By the reign of Gallienus, as Christophe Hugoniot observes, it had become far more exclusive.Footnote 138 There are multiple possible explanations for this. The Carthaginian elite may have closed ranks, or candidates disappeared. It may also plausibly be connected to the restructuring of Carthage's administrative territory under Septimius Severus and Caracalla, which — for good or bad — had deep consequences for the towns in the area. Apart from the Flavian towns to the west and south, few emperors intervened in the urban hierarchy of the area. Antonine ‘creations’ are isolated instances, reflecting the pace of petitions rather than any deliberate policy to bestow municipal rights. All of them, moreover, lay outside the Carthaginian territory.Footnote 139 The attitude of Severus and Caracalla was strikingly different: in sweeping fashion, they granted municipal rights to scores of ciuitates, which fused with pagi to form their own patriae. All attested foundations lay within the Carthaginian pertica, which was effectively dissolved. No further pagi are known, and no pagus is known to have been emancipated before the Severans. Jacques Gascou called the measure ‘assez brutale’, and did not doubt that it was deliberate.Footnote 140