The Liberal International Order (LIO) has structured relations among capitalist, democratic, and industrialized nations since the late 1940s; it has also influenced international affairs in general. It is now being challenged in multiple and wide-reaching ways: populist, nationalist, and antiglobalist movements within its core members; the rise of peer competitors with different, more state-centered economies and authoritarian political systems; and the threats of climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic that exacerbate other challenges to the LIO. This is not the first time the postwar LIO has faced difficulties, of course. Like Mark Twain's death, rumors of the demise of the LIO have been greatly exaggerated. The LIO has proven resilient in the past, and it may prove to be so once more. Yet, the combination of internal and external challenges suggests that this time might be different.

International Organization (IO) grew up alongside the LIO, first as almost a journal of record describing events at the United Nations and its related institutions and, later, as a venue for some of the most innovative and important scholarship on this order. Many of the key concepts used to interpret the LIO first appeared or received serious scholarly attention in the pages of this journal: transnational relations; hegemony; domestic structures; international regimes; embedded liberalism; multilateralism; international norms; the function and design of international institutions; the process of legalization; socialization. The journal has long been a premier outlet for the study of economic interdependence, alliances, war, human rights, the European Union, and other substantive issues central to the LIO.

At the seventy-fifth anniversary of IO, we can justly celebrate our collective success in getting much right about the origins and functions of the LIO. At the same time, few of the current challenges to the LIO were fully anticipated even by the best scholarship published in this journal, or elsewhere. It is appropriate to take stock of the field of international relations (IR), highlight what we have learned, and importantly reflect on our collective “blind spots” to help identify a research agenda for the future.

We begin by identifying what we mean by the Liberal International Order. We then turn to the challenges currently confronting this order, and finally address what we collectively missed or pushed to the side in studying it.

The Liberal International Order

The LIO has been a remarkably successful institution. Created after the horrors of World War II, the LIO is credited with collectively defending the West against an expansionist Soviet Union, supporting the rise of free trade and international capital mobility, spreading democracy, and promoting human rights. It is generally agreed that the LIO facilitated unprecedented cooperation among the states of North America, Western Europe, and Japan after 1945. While cause and effect are impossible to establish at this level of generality, within the core of the LIO the now-famous “democratic peace” has prevailed, and the core members of the LIO have formed a pluralistic security community in which the use of military force between members is no longer contemplated.Footnote 1 The LIO helped solve the collective-action problem that thwarted past efforts at deterring common security threats. Although civil wars grew after the end of the Cold War, none erupted within the core members of the LIO (with the exception of Northern Ireland). Cooperation extended to the liberalization of international trade and capital. Benefiting from a greatly expanded division of labor, the countries that formed the core of the LIO enjoyed historically high rates of economic growth and standards of living. Real per capita income in the United States and Western Europe exploded after World War II and more than tripled between 1950 and 2016. Over time, economic liberalism expanded to many other countries, including China and India, leading more people out of absolute poverty than at any other time in human history. The LIO helped consolidate democracy in the formerly fascist or militarist Axis countries and promoted the spread of democracy globally. Equally important, the LIO established a global human rights regime that, though still problematic in many places, has greatly improved human rights practices in many countries.Footnote 2

To point out the correlates of the LIO is not to take a Panglossian view of international politics. Members of the LIO have not coped well with global climate change or with the COVID-19 pandemic, to put it mildly.Footnote 3 As we shall see, the income gains have not been distributed evenly either within or among countries.Footnote 4 But for many people in many countries, the LIO is associated with substantial increases in the quality of their lives. The remarkable progress of the last seventy-five years makes challenges to the LIO puzzling.

Constitutive Components of the LIO

Despite its many successes, the Liberal International Order remains a contested concept.Footnote 5 Common descriptions of the LIO include adjectives such as “American-led,” “open,” and “rule-based.” These adjectives are insufficient to capture the liberal part of the order. Scholars also debate whether there is a single LIO or several LIOs. We opt for the former usage since, as we argue, the LIO is distinct from other international orders in retaining a core set of principles and practices. At the same time, the LIO is a dynamic order exhibiting different features across time and space. From a historical perspective, the LIO of the 1950s has different features than the LIO of the 2010s, and both certainly differ from the closest analogy, the Pax Britannica of the nineteenth century. We can organize the liberal order into separate sub-orders, largely along issue-specific or regional lines. The international trade order and the international human rights regime are both sub-orders of the LIO, for example. With regard to space, we find several distinct regional orders, which can all be labeled “liberal” to some degree. They constitute varieties of liberal orders, especially with regard to the regional embeddedness of the welfare state or the degree of supranational governance.Footnote 6 While the international community as a whole universally accepts some features of the LIO, other parts are subscribed to by only a limited number of states and other actors. The International Criminal Court, for example, is a core institution of the human rights regime, but not even all liberal states have accepted its jurisdiction (the United States has not, for example). In this issue, when we refer to the LIO, we restrict our attention to elements of the order that have existed since 1945 and are in theory open to all states that are willing to accept the rules—that is, that aspire to be universal. Regional orders such as the EU coexist with the global liberal order but are not our focus. What are the constitutive features of the LIO? What do these features have in common? We start by discussing the three terms comprising the concept and then analyze some of the contested issues surrounding it.

Order

On the most basic level, orders connote patterned or structured relationships among units. Molecules, as a group of atoms held together by chemical bonds, constitute an order. Here, we are dealing with social orders, which can be more or less spontaneous or rule based. Spontaneous social orders result from the uncoordinated action of human agents. But members of an order can also intentionally construct and enforce rules that govern social orders. In IR, think of the difference between the balance of power as a spontaneous order as conceived by Waltz, or as a socially constructed order as understood by Morgenthau, Kaplan, or Bull, to clarify the distinction.Footnote 7

Rules, norms, and decision-making procedures characterize the LIO, and the coordinated action of actors, both state and nonstate, sustains the LIO. Yet, we do not believe that it is sufficient to describe the liberal order as “rule based,” since both the Concert of Europe and the Westphalian order are rule based, but not liberal. Rules are a necessary but insufficient component of the LIO.

International

Understanding the “international” aspect of the LIO requires understanding the relationship between liberalism and what is usually called in IR the “Westphalian international order.” We use the terminology of a “Westphalian” order, as is common practice, even as we recognize that it is historically incorrect to suggest that the current international order was established by the Peace of Westphalia ending the Thirty Years’ War in 1648. What we describe as “Westphalian order” came about only in the nineteenth century, if not later.Footnote 8 Indeed, Tourinho argues that the Westphalian order truly emerged only alongside the LIO after 1945, spearheaded by Latin American states.Footnote 9 The 1933 Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States summarizes the Westphalian order, and this convention was subsequently incorporated in the Charter of the United Nations. According to the Westphalian order, the principal units of the international system are sovereign nation-states. In addition, the Westphalian order requires the recognition of states by the international community of states, and specifies the corollary principle of noninterference in domestic affairs by other states. This last principle began with Vattel and other eighteenth-century thinkers, but attained broad acceptance only when incorporated into the UN Charter.

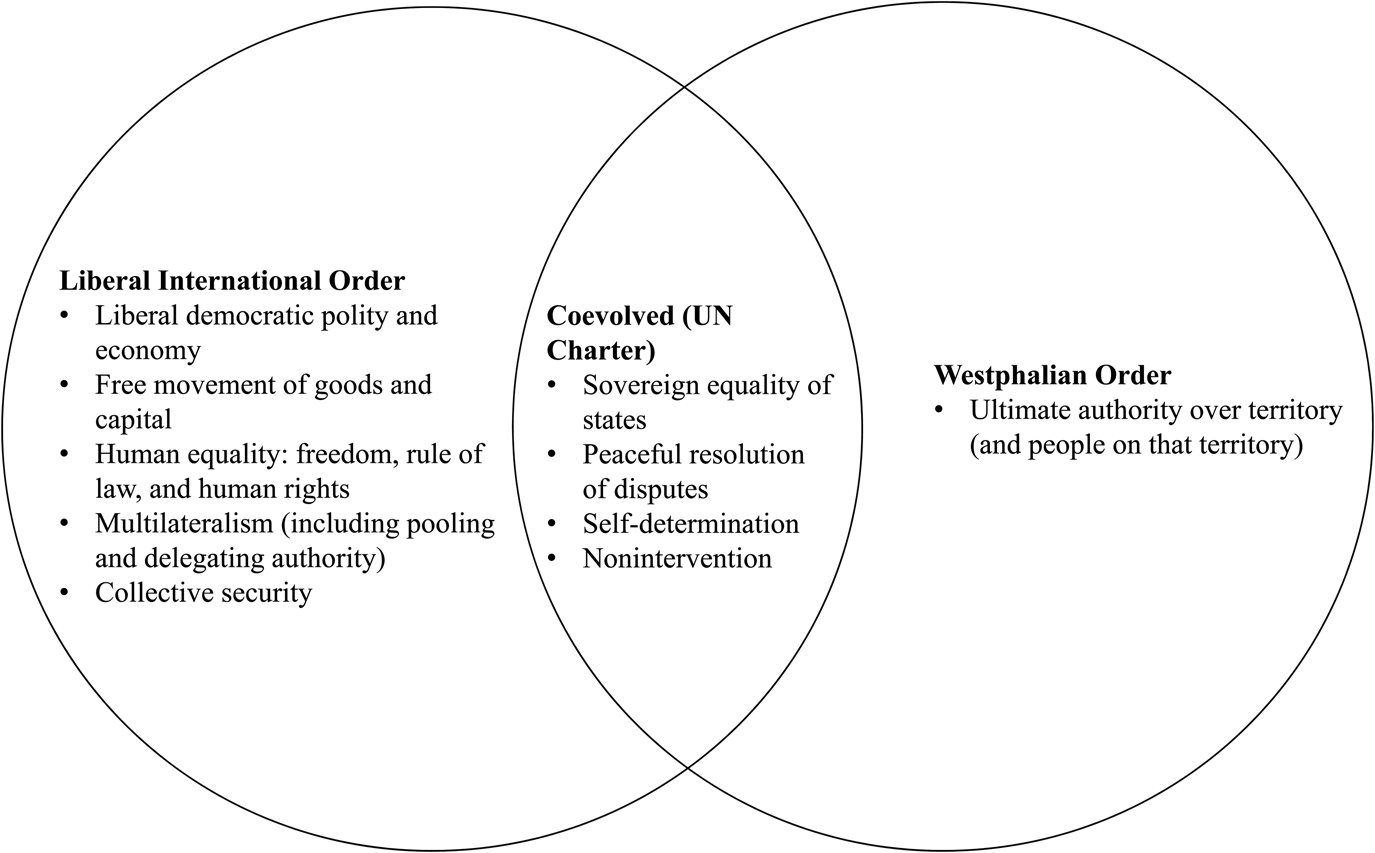

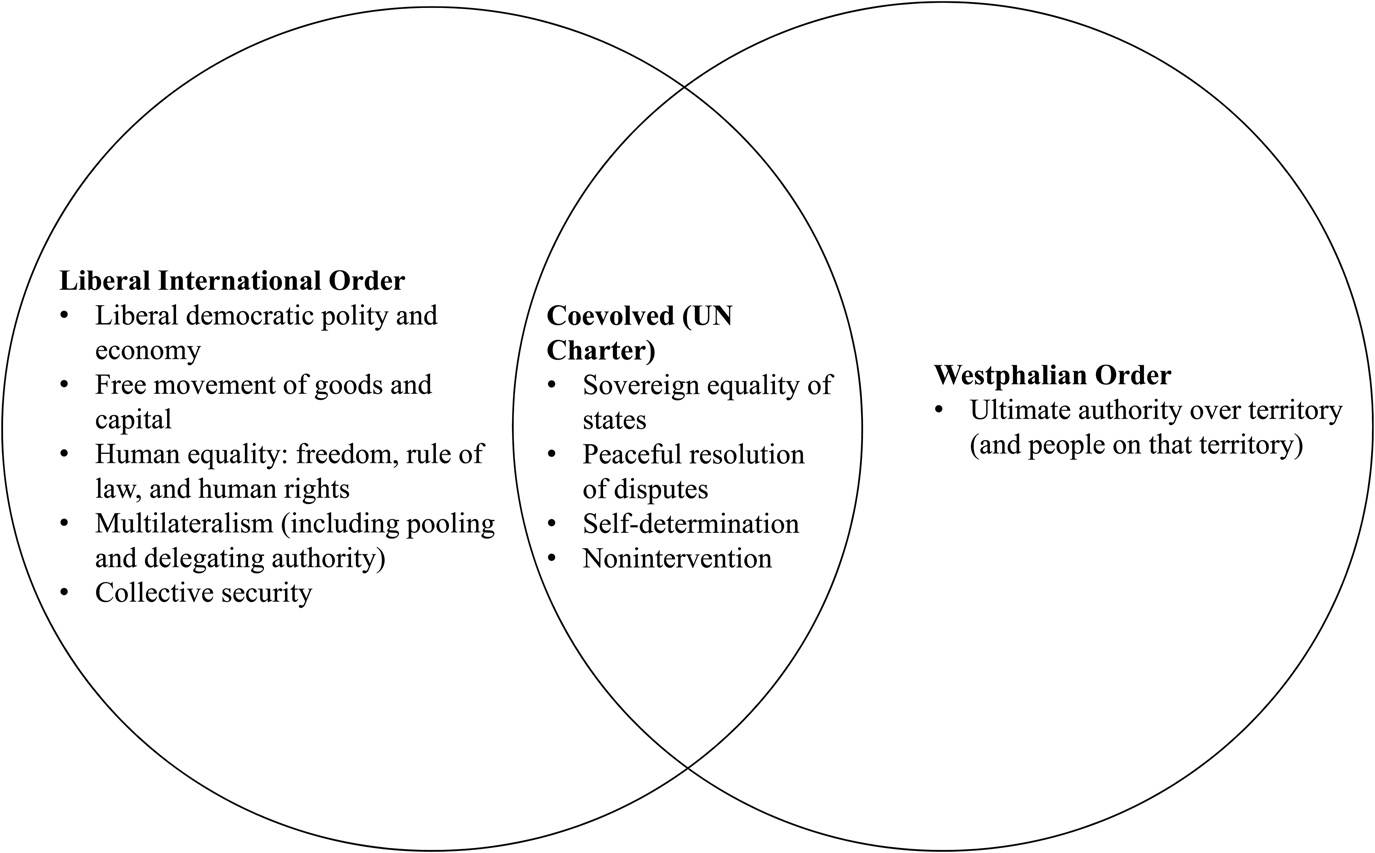

The LIO coexists with the Westphalian order, but the two have a problematic relationship. As Tourinho argues, since World War II Westphalia and the LIO have co-constituted each other and have coevolved. Yet, the LIO differs from the Westphalian model and modifies or sacrifices its principles in a number of ways. One way to visualize the relationship between the Westphalian order (an order that, of course, was always an ideal rather than actual practice) and the LIO is to picture them as partially overlapping sets of norms and practices (Figure 1). On the one hand, Westphalia and the LIO share common principles such as the self-determination of states, the peaceful resolution of disputes, and noninterference in internal affairs. Moreover, both the Westphalian order and the LIO emerged from colonial and imperial relations and were rife with tensions among their various principles, and between those underlying principles and state practices.Footnote 10 On the other hand, the LIO contains principles not present in Westphalia, such as respect for human rights or rights of collective intrusion to protect liberal values (see below).

Figure 1. The LIO and the Westphalian order

Liberal

“Liberal” is the most difficult and most controversial term in the LIO concept. At its (philosophical and normative) core, “liberal” connotes a belief in the universal equality of individuals and posits freedom as well as individual and collective self-determination as the highest human aspirations. Representative democracy and the rule of law guarantee individual freedom while subjecting it to certain limits in the interest of the collective good. Rights protecting individual freedom have expanded over time. In other words, as developed in Kant's Perpetual Peace, a liberal order contains institutional structures premised on the equality of all individuals and designed to allow individual freedom to thrive.Footnote 11 Importantly, the term is drawn from a classical or enlightenment understanding of liberalism. As a result, notions such as “neoliberalism” (the withdrawal of the state from regulating the economy) or “embedded liberalism” constitute historical varieties of a broader and more encompassing understanding of liberalism. Paradoxically, while this understanding of individual equality and freedom is at the core of the LIO, states and individuals can subscribe to these aspirations without buying into its philosophical foundations. That is, one does not have to accept liberal philosophy to subscribe to the notion of human rights, which can be justified by various philosophies and world religions, or to participate in a liberal international economy. We distinguish between political, economic, and international institutional components of liberalism.Footnote 12

Political liberalism

The LIO is grounded in the rule of law that applies equally to weak and strong in the international system. The sovereign equality of states, for instance, is ultimately based on a notion of human equality.Footnote 13 The more demanding components of political liberalism pertain to an international order that protects (individual) human rights as well as political participation and democracy on the domestic level (Figure 1). In this sense, autocratic regimes and political liberalism stand in tension with one another in a way that other parts of the LIO do not. The more domestic orders are subject to international law and jurisdiction, the more the LIO contradicts Westphalian principles. Prominent examples include the International Criminal Court establishing the principle of individual criminal responsibility for crimes against humanity, or the Responsibility to Protect.Footnote 14 Both Western and non-Western societies are now contesting precisely these principles.

Economic liberalism

In the economic sphere, the LIO has taken at least two different forms. One reflects a set of classically nineteenth-century liberal policies, including market-capitalist rules within countries, free trade between countries, international capital mobility, and national treatment of foreign direct investment. This version of economic liberalism is more widespread in the twenty-first century than it was in the early decades after World War II. In fact, many critics of the LIO see the current version of economic liberalism as “hyperglobalization” and understand it to be a dangerous betrayal of the intentions of those who constructed the LIO in the mid-twentieth century.Footnote 15 It is important to note here that—except within the EU—these classically liberal policies do not extend to the movement of people across national borders, partially insulating the Westphalian order from the liberal economic order but also raising tensions that Goodman and Pepinsky identify as central to explaining contemporary “bottom-up” challenges to the LIO.Footnote 16

The second form marries the nineteenth-century conception of liberalism to a twentieth-century conception that embeds markets within a social contract. As Ruggie powerfully argued, the version of economic liberalism originally constructed by the Bretton Woods Institutions is best understood as “embedded liberalism.”Footnote 17 While championing moves toward the free movement of goods and services across international borders, architects of the order also understood that such movements can be highly disruptive and that societies need to be sheltered from the most severe risks if the order is to endure. Robust welfare states that could compensate those negatively affected by economic openness thus came to be a central element of embedded liberalism.Footnote 18 Importantly, though, architects of the order understood compensation as a domestic solution to distributional problems, not an international one. Limits on capital mobility in the Bretton Woods system also represented an essential compromise of embedded liberalism. While capital moved freely to settle current accounts, until the 1980s states maintained varying levels of controls on capital-account transactions.

Economic liberalism per se does not contradict the Westphalian system. However, the more neoliberalism prescribes particular domestic economic policies (such as independent central banks, privatization and deregulation, or pressures on welfare-state systems), the more the tension with the Westphalian order increases. Population flows across national borders especially illustrate this tension, as international income disparities and social unrest draw economic migrants and refugees who are not fleeing political persecution as envisioned in the founding international laws. An economically efficient allocation of labor across national borders creates tensions between liberalism and Westphalia. As Goodman and Pepinsky (this issue) note, immigration generates both economic growth and political friction in receiving states, as liberal democratic obligations for inclusion and rights cannot be ignored. It is no coincidence that current contestations of economic liberalism mostly pertain to neoliberalism and its tensions with the Westphalian order (Börzel and Zürn, this issue).

Liberal internationalism

International institutions that are part of the LIO rest on foundations of principled multilateralism. As a constitutive principle, multilateralism does not simply refer to the coordination of policies among more than two states. It represents, as Ruggie put it, “an institutional form which coordinates relations among three or more states on the basis of ‘generalized’ principles of conduct, that is, principles that specify appropriate conduct for a class of actions, without regard to the particularistic interests of the parties or the strategic exigencies that may exist in any specific occurrence.”Footnote 19 In Ruggie's conception, multilateralism combines structure and purpose, with the latter embodying a notable willingness to cede authority to allies and institutions in the pursuit of long-term stability and economic gains. The Most Favored Nation clause in the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and the World Trade Organization (WTO) exemplifies such generalized principles, as does the principle of collective security embodied in the UN Charter. Moreover, principled multilateralism encompasses the peaceful resolution of conflicts (without excluding the right to individual or collective self-defense; see UN Charter, Art. 51). The LIO also contains a collective commitment to global governance in the sense of an aspiration to work toward a common global good.Footnote 20

The collective security components of the LIO have to be understood in the context of the experience of two world wars in the early twentieth century. The same holds true for security alliances among democratic states such as the North Atlantic Treaty Alliance (NATO), which were not traditional alliance systems but security communities among like-minded states.Footnote 21 Last but not least, liberal internationalism led to various arms control regimes, not just US–Soviet/Russian ones during the Cold War and beyond, but also multilateral ones such as the nuclear nonproliferation regime and the treaty system banning landmines.Footnote 22

Liberal internationalism does not necessarily contradict the principles of the Westphalian order. Tensions arise, however, when multilateral institutions encompass provisions regarding the pooling and delegating of authority to supranational organizations,Footnote 23 from majority voting in international organizations (IOs) and regional organizations to supranational dispute settlement systems and international or regional courts. As Goldstein and Gulotty as well as Börzel and Zürn argue (both in this issue), contestions of the LIO arise precisely because of these supranational components of liberal internationalism.Footnote 24

The LIO: Universal or Regional?

To what extent is the LIO universal, and to what extent is it confined to liberal democratic states? The LIO encompasses a central paradox. It follows from the principle of individual equality that the LIO as a political order is “open,” almost by definition. If all humans are equal, all should have the same rights and standing and thus be capable of entering the international order.Footnote 25 At the same time, however, these aspirations to universalism allow states to subscribe to the LIO or parts of it without themselves being “liberal.” China is an obvious example.Footnote 26

Given this paradox, why would a state go through the process of joining a liberal IO if it does not share the core values of that organization? And why would liberal states encourage membership of illiberal states? On the first question, the reasons states join are myriad and range from direct material benefits to more diffuse reputational and legitimacy concerns. States that do not accept principles of liberal democracy, and even reject some of the tenets of market capitalism, have joined the WTO and other multilateral economic institutions. Illiberal states may join human rights institutions as a way to shore up their standing as members of the international community or in the hope of gaining various types of side payments. Once IOs have large, nearly universal memberships, states that stay on the outside can be seen as pariahs and suffer negative consequences merely for not pretending to accept liberal principles. On the second question, liberal states encourage membership not only because of their universal values but also because they anticipate that participation in the LIO will socialize countries into altering their domestic political structures and embracing liberalism. The LIO, therefore, creates dynamics whereby organizations created by liberal states can become full of states that are illiberal.

As a result, at least in theory, the entire international community accepts many features of the LIO, and this universal acceptance goes beyond the zone of overlap between Westphalia and the LIO. UN members in principle accept the supreme authority of the Security Council in questions of war and peace, including the authority to legitimize military interventions. Each and every state in the international community is committed to some basic human rights, particularly physical integrity rights. And despite all contestations, few states reject economic liberalism in principle, at least not since the end of the Cold War.

However, with respect to other parts of the LIO, states pick and choose how to participate. Note that not only liberal and democratic states accept the most intrusive LIO institutions. Russia and Turkey are (still) parties to the most intrusive (regional) human rights regime of the world, the European Convention on Human Rights. In contrast, the United States has historically been reluctant to accept deep intrusions into its “Westphalian sovereignty”; for example, it has fought tooth and nail against the International Criminal Court. It never accepted the more intrusive provisions of the international climate change regime, such as the Kyoto Protocol, and withdrew from the 2015 Paris Agreement under President Donald Trump (though President Biden has returned). Importantly, it is a historical myth that the most intrusive and distinctive parts of the LIO have all been introduced by Western democracies, let alone by US hegemony. The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights owes much of its substantive content to Latin American states.Footnote 27 The Responsibility to Protect was “invented” in sub-Saharan Africa, even though many African states now contest its principles.Footnote 28 All this suggests, as we said at the beginning, that the LIO is not a singular thing but a dynamic order that applies more or less broadly, and has evolved over time, and will likely continue to evolve in the future.

Challenges to the LIO

Is the LIO under threat? How do we know whether it is or is not? Such questions have structured the field of IR, and the relationship among IO, the discipline, and real-world events, since IO's founding. IO transformed itself from a journal on the United Nations to a journal of international political economy and IR in general with the premise that something fundamental was changing in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The special issue on Transnational Relations and World Politics captured the emerging variety of actors on the global stage.Footnote 29 A second special issue, Between Power and Plenty, explicitly sought to explain variations among the advanced industrialized economies in their responses to the crisis then perceived to be underway, led not least of all by the first oil shock in 1973.Footnote 30 In 1975, Robert Gilpin, worried that US hegemony was rapidly waning, contemplated “Three Models of the Future.”Footnote 31 The end of Bretton Woods, the rise of Japan, and the second oil shock convinced many observers that the LIO was indeed in trouble. In 1983, the special issue on International Regimes grappled with the idea of change of versus within regimes.Footnote 32 While that debate was largely inconclusive, it was clearly motivated by an underlying concern among IR scholars that the global order was undergoing potentially foundational shifts.

The LIO has been challenged from the very beginning, from forces both within and without, and by feedback between internal and external dynamics. We organize the challenges into internal and external categories, but it is important to recognize that these two levels interact in a dynamic manner. While the Bretton Woods conference institutionalized multilateral principles for monetary and development affairs, its calls for similar rules for trade faltered. Negotiations did lead to a charter for an International Trade Organization but, rejected by protectionists in the United States, it was stillborn. Instead, an initially informal bargaining forum on tariffs, the GATT, began to structure trade relations. After this inauspicious start, the GATT grew through repeated rounds of negotiations and eventually became formalized as the WTO.

As the rest of this section details, many of the current challenges to the LIO within Western societies come from the political right. However, former challenges came mostly from the left. Two notable examples are the New International Economic Order (NIEO) and protests against the WTO culminating in the Battle of Seattle. Calls for an NIEO from the Non-Aligned Movement in the 1970s represented demands from developing countries that were integrated into the LIO to various degrees but felt that they were deeply disadvantaged by its liberal economic principles. The NIEO envisioned fundamental transformations to the liberal economic order.Footnote 33 The main legacy of the NIEO was the creation of a number of natural resource cartels in the global South as well as UNCTAD, the UN Conference on Trade and Development. OPEC, a model the NIEO attempted to export to other commodity producers, did in fact pose a significant threat to the LIO. The Battle of Seattle protests in 1999 were the largest protests ever against an annual meeting of an economic IO, and echoed the NIEO in their call for limitations on free trade. However, while the NIEO envisaged more intrusive global institutions, protests against the WTO saw it as too intrusive into domestic politics and signaled a decisive challenge—again from the left—to neoliberalism.Footnote 34

Despite these earlier challenges, the LIO proved robust. Soon after the International Regimes special issue, many scholars came to the conclusion that the LIO had survived and was, in fact, spreading its reach further south into the Western Hemisphere, east into new parts of Asia, and soon even into Eastern Europe.Footnote 35 Taking a longer historical perspective, Ikenberry drew attention to the ways in which hegemons, or great powers more generally, have always established regimes and institutions that allowed patterns of interaction to persist in the face of fundamental power shifts.Footnote 36

The LIO has been long attacked in fundamental ways. It has long persisted. Is anything different today, or are we just replaying decades-long debates? This section addresses what we see as the most pressing challenges to the LIO today. Most of the articles in this issue address challenges to the LIO that arise from within the LIO itself, coming from both political and economic sources. The remaining articles address challenges to the LIO arising from powers and forces outside the order. In this era of change, turmoil, and global pandemics, it is easy enough to assume the role of Henny Penny (also known as Chicken Little) from the children's story who, hit by an acorn, runs around telling all the other animals that the sky is falling. That is not our intent here. Indeed, the LIO has been resilient in the past, and we return to this theme at the end of this section. But the LIO is today being challenged from within and without in unprecedented ways. While much of the literature has focused on challenges that have resulted from the exclusive nature of the LIO, we find that its attempts to be more inclusive have also created deep challenges.

Readers will note that this special issue is rather short on dealing with security issues, even though IO has covered them extensively, particularly civil wars and nonstate violent actors, in recent years. We focus on issue areas where we find the deepest challenges to the LIO. While the nuclear nonproliferation regime and various other arms control agreements are under siege or have been abandoned altogether, the current onslaughts appear to be targeted more at liberal internationalism and multilateral institutions in general than at security institutions in particular. Morover, NATO, as the prime security institution in the transatlantic core, appears to be alive and kicking, despite all the challenges facing the transatlantic security community and former President Trump's attacks on the institution. If the LIO unravels, security institutions may come under greater threat, deserving of future attention. Here, though, we focus more on the most salient challenges to the core components of the LIO.

Challenges from Within Liberal Core States: Internal Contradictions and the Rise of Nationalist Populism

Some of the contemporary challenges to the LIO arise from the nature of liberalism itself and contribute to the resurgence of nationalist-populism in core members of the order. Without any claim to being exhaustive, we note that challenges from within liberalism have developed in three broad ways.

First, liberalism, particularly in its neoliberal form, exacerbates who wins and who loses from economic globalization. These effects are relatively predictable, if underappreciated, but also appear to be more complex than previously understood. Broz, Frieden, and Weymouth (this issue) argue that the effects of free trade and economic openness generally, magnified by the financial crisis of 2008–2010, are now most evident at the level of communities, with welfare and political implications that cascade through local societies.Footnote 37 Rogowski and Flaherty (this issue) show that unequal returns on talent magnify the disruptions of globalization and widen income inequality, a major cause of populism.Footnote 38 In these ways, though the connections and processes are subtle, economic liberalism itself contributes to the backlash against globalization and to nationalist-populist movements.

In a similar way, liberalism challenges its own political foundations in ways that are now more obvious but were also underappreciated. The very political openness of liberalism creates avenues for the the subversion of liberalism. As Farrell and Newman (this issue) claim, the freedom of expression central to liberalism, instituted in extreme form in the open architecture of the internet, has allowed autocratic states that have perfected misinformation strategies at home to attack the political foundations of more democratic states.Footnote 39 Likewise, Adler and Drieschova (also this issue) argue that liberalism is being undermined by strategies of truth subversion.Footnote 40 Liberalism is based, in part, on a particular conception of truth developed during the Enlightenment and founded on reason. Political liberalism opens the door, however, to those who would challenge this conception of truth by appeals to belief and emotion. The populist denial of the COVID-19 pandemic or climate change, including various conspiracy theories, is a case in point. Again, these political and ideological challenges are seemingly natural consequences of liberalism and might have been anticipated but were poorly understood.

Second, liberalism contains contradictions within its own program. Most importantly, for liberalism to construct itself it had to be in some ways illiberal, which in turn rendered it less responsive to citizens. In their contribution, Goldstein and Gulotty maintain that policies of free trade meant that governments, especially in the United States, had to insulate the policy process from pressure from protectionist interests.Footnote 41 As free trade became institutionalized, opposing groups were excluded from the process and eventually rebelled against it. Likewise, Börzel and Zürn argue that to build liberal internationalism, supranational authorities—especially the EU—became increasingly insulated from the public and more technocratic and intrusive, creating resentment and a nationalist backlash.Footnote 42 Indeed, building on this analysis, De Vries, Hobolt, and Walter (this issue) explore how international institutions have spawned domestic opposition and new demands by mass publics for a greater voice in politics, often mobilizing support for antiliberal policies.Footnote 43 Here, in an almost dialectical fashion, liberalism contains the seeds of its own challenges.

Third, liberalism in both its economic and political forms challenges notions of national identity. Simmons and Goemans (this issue) extend the distinction mentioned earlier between the Westphalian order and the LIO and point to an underappreciated tension between norms of territorial sovereignty, central to the former, and norms of universalism, critical to the latter.Footnote 44 These norms clash in the current period in appeals to nationalism and the “repatriation” of sovereignty. Goodman and Pepinsky, in turn, highlight the conflict engendered by inclusive policies of immigration and the rules and norms governing legitimate participation in a national polity, producing new battles today over “who are we?” This cuts to the core of democratic political theory and nationalism.Footnote 45 Búzás (this issue) describes the history of IR as a continuing struggle between traditionalists who defend racial hierarchies and transformationalists infused with liberalism's belief in human equality who advocate “multiculturalism.”Footnote 46 Intersecting the other challenges, this central cleavage animates opposition to the LIO by both traditionalists, who see equality as going too far in displacing white patriarchies, and transformationalists, who believe multiculturalism has not gone far enough. All of these papers call attention to the problems of identities that clash in different ways with liberalism and the LIO.

These various challenges combine in growing nationalist-populist opposition to the LIO from within core states. Parties and movements that display elements of the following three characteristics are on the rise in the West and in other places around the world:

Nationalism, the promotion of the interests of a particular state at the expense of others. In its more extreme forms, nationalism asserts the superiority of a certain national identity over other identities. While nationalism per se has been around for quite some time, the transnational linkages among nationalist forces as well as the diffusion of parochial nationalism are recent phenomena.

Populism, the promotion of the interests of “the people” as opposed to the views of elites. In general, populism entails a rejection of the elite consensus and an assumption of a homogeneous “will of the people” that rejects pluralism and is often defined in exclusionary nationalist terms.

Authoritarianism, the rejection of core elements of liberal political orders, such as fair and free elections, freedom of the press, and an independent judiciary.

All three of these political dynamics have existed throughout the LIO era. However, the nationalist challenge exploded in the late 2010s. The election of Donald J. Trump in 2016 on a populist, nationalist, and “America first” platform transformed the government of the core guarantor of the LIO to become its strongest challenger. That more than 74 million Americans voted for Trump in 2020 suggests how vibrant this challenge remains, as does the storming of Congress by supporters of President Trump instigated by the president himself on 6 January 2021. Nationalist populism, however, is not confined to the United States. Many European governments either include or are dependent on parliamentary support from authoritarian populist parties, and more than a quarter of European voters voted for an authoritarian populist party in their last national election.Footnote 47 Brexit is a prime example of nationalism on the rise in the core of the LIO.

While authoritarian states outside the Western core have long participated in the LIO, relatively liberal non-Western states that have been important actors in the LIO are also experiencing an upsurge in authorianism. The prime minister of India since 2014, Narendra Modi, is a Hindu nationalist and appears to be reconfiguring India as a Hindu state. Jair Bolsonaro, the president of Brazil, represents a far-right political ideology and has openly and frequently expressed sexist, homophobic, and pro-torture sentiments, in addition to questioning the necessity of democratic governance. In the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte represents a similar right-wing and nationalist agenda. The same holds true for Benjamin Netanyahu, the longest-sitting prime minister in Israel's history.

A question closely related to the rise of populist parties is whether core Western states are seeing fundamental political realignments. In the United States, whether the Democratic and Republican parties will shift their bases of support in lasting ways and open up new cleavages in American politics is a perennial topic. Nevertheless, evidence of realignment is growing. From a political economy perspective, the main cleavage in American politics for at least the last century has been between internationalist actors, primarily representing capital and export-oriented agriculture, and low-skilled or service-sector labor. What we seem to be observing now, in a challenge to both the Republican and Democratic parties, is a shift to an urban–rural divide. If the main cleavage in domestic politics is between urban actors, including both internationalists and those focused on the domestic economy (e.g., retail services), and rural actors, that represents a significant shift in the fundamental divide in American politics. One piece of evidence of this emerging cleavage is the recent rise of “rural consciousness.”Footnote 48 The 2016 presidential election and the 2018 midterms saw urban districts swing further to the left than they had in 2008 or 2012, while rural districts swung further to the right, a trend that was magnified in the 2020 election.Footnote 49

In Europe, in addition to the traditional Left–Right socioeconomic cleavage, a new cleavage is emerging. It increasingly separates those individuals and political parties with liberal/cosmopolitan attitudes (e.g., the German Greens) from those with nationalist/authoritarian beliefs (e.g., PiS in Poland, Orban's Fidesz in Hungary, Lega in Italy). Data show that this cleavage has led to political realignments across Europe.Footnote 50 It has mobilized exclusive nationalist attitudes among citizens and translated them into political and voting behavior, in a way similar to the US case. At the same time, Green parties in various European countries have mobilized the liberal/cosmopolitan end of the cleavage.

Finally, many nationalist-populist movements have been charged with anti-immigrant sentiment, opening an old but newly resurgent cleavage. The role of migration in the LIO has always been difficult, with inconsistent policies and messages. As noted, free labor migration was never part of the LIO. Unlike goods, services, and capital, labor has never had the advantage of free movement across borders, except within the EU. Still, labor migrants played a central role in postwar reconstruction in countries like Germany and the UK, and states have struggled to balance the rights of political liberalism with the national boundaries inherent in the Westphalian system.Footnote 51 On the other hand, a strong set of international norms and laws have grown around the treatment of refugees and asylum seekers, driven in part by the failure to protect Jewish refugees during World War II. The principle of nonrefoulement, which forbids countries from returning asylum seekers to territories where they would face persecution based on demographic and political factors, is firmly established in customary international law.Footnote 52 Further refugee rights have been codified in the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. In spite of this body of international law, refugee-receiving states vary widely in their treatment of those crossing their borders, with some (such as Germany) providing relatively generous benefits and others (such as the United States under Trump) withdrawing protections and explicitly adopting deterrent policies.Footnote 53 Migration has thus always been a challenge for the LIO, and its interaction with domestic politics is fueling one of the strongest contemporary challenges.

What accounts for the rise of these populist, nationalist, and often authoritarian parties? For many observers, ourselves included, the LIO was understood to have been “institutionalized,” rendered robust by IOs and interests vested in their continuation. The growth of internationalized business and the development of highly integrated global supply chains were expected to propel globalization ever forward and prevent any protectionist backsliding. Yet, throughout the developed world, international business has proven remarkably weak in the face of the populist and economic nationalist wave that is reshaping national and international politics; the global supply chains on which those businesses depend have shown themselves to be vulnerable in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. A popular narrative, especially in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, is that globalization combined with the gutting of the welfare state created resentment and discontent. While this may well be the case in some parts of the world, it is also the case that even states with robust welfare states have seen a surge of right-wing populism. The Sweden Democrats, for instance, a radical-right party that was very small in 2002, is now Sweden's third-largest party.Footnote 54 In turn, at least in the United States, the populists are also less opposed to government-led redistribution, at least if the money is directed to themselves, than the fiscal conservatives who formerly dominated the Republican Party.

There are no easy answers to the questions of why and why now? The essays in this issue point to deeper causes and trends. No one factor is determinative. Taken together, though, the challenge from within is significant. Sorting through the various explanations explored here, individually and in combination, will be a subject of continuing research as we try to parse out the effects of previously underappreciated dynamics within the LIO.

External Challengers: China and Beyond

At the same time the LIO is challenged from within, it is also—and perhaps not coincidentially—being challenged from without, that is, by processes that are only loosely related to liberalism itself and from states previously excluded from or only weakly integrated into that order. Closely related to the internal challenges we described, Mansfield and Rudra point to how technological change has overwhelmed institutions within the LIO that were supposed to mitigate or at least slow economic displacement.Footnote 55 Drawing on Ruggie's concept of embedded liberalism, they argue that existing institutions have proven inadequate to their social purpose under the accelerating pace of innovation and, especially, increasingly disaggregated global production chains. In a similar way, though one might connect it to liberalism's emphasis on free markets, climate change is a threat to the global environment and humans for which liberalism does not alone bear full responsibility. Colgan, Green, and Hale usefully shift attention from problems of collective action to assets held by firms and groups who would lose from policies designed to slow climate change.Footnote 56

China, now emerging from its “century of humiliation” as a global power, challenges the LIO in numerous ways. Is the rise of China a fundamental challenge to the LIO, or has the country been sufficiently co-opted into the order that it is now a “responsible stakeholder?” It is worth noting some of the spectacular achievements of the Chinese economy over the last forty years. Since 1979, it has achieved a remarkable average annual GDP growth rate of 9.5 percent. It has thus doubled its GDP about every eight years and brought some 800 million individuals out of poverty.Footnote 57 Scholars and other commentators debate whether China's success is due to the LIO, or due to its grudging acceptance of the LIO, or a core challenge to the LIO (or all three).

China is not a democracy and shows no tendencies toward democratization. With reference to our understanding of the Westphalian order and the LIO, the Chinese government is clearly more comfortable with the underlying Westphalian values of sovereignty and noninterference. It adamantly rejects outside interference in its civil obligations, which conveniently excuses its own human rights violations. At the same time, it has joined the major multilateral IOs, benefited in tremendous ways from these memberships, and even replicated at least the form of these organizations as it moves into a leadership role on the global stage, including through the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

As Weiss and Wallace examine in this issue, China has engaged, successfully to date, in a delicate balancing act.Footnote 58 The government accepts economic liberalism and would likely not survive without its growth-producing force. At the same time, it rejects core concepts of the LIO such as democracy, a free press, and other human rights at the domestic level. It only partially accepts the rule of law. The IR literature debates whether China is a status quo power or whether its state-capitalism economic system will lead it to challenge the LIO and seek to establish an international order more favorable to itself. Johnston and others argue for the former, while others are more skeptical, maintaining that even if China has not yet attempted to break out of the LIO we cannot predict what it will do in the future.Footnote 59 Still others see the future as more open and, indeed, dependent on actions by the Western powers. Trade war between the United States and China may well threaten China and cause it to seek a more autonomous development path and export markets outside of US control, creating the possibility that regional trade blocs might emerge reminiscent of the 1930s.Footnote 60 Weiss and Wallace theorize that what issues China will and will not defend on the world stage is a function of how central the policy is to the survival of the regime and how heterogeneous the interests are surrounding that policy within China. As they show in the case of environmental policy, the regime can be quite responsive—and internationally responsible—when the broad public demands action.

China is not the only authoritarian state that might challenge the LIO or at least certain aspects of it. Focusing on the compelling human need for recognition, Adler-Nissen and Zarakol connect the politics of resentment by the groups within countries discussed by others with the same attitudes and strategies of countries that have been excluded from the LIO.Footnote 61 Denied the benefits of integration, or perceiving themselves as not fully benefiting, “outside” powers like Russia, Turkey, and Venezuela are now attempting to delegitimate and ultimately overthrow liberalism. As the Tourinho and Búzás articles in this issue also note, countries excluded from the LIO have constantly both challenged it and bought into some of its core principles.Footnote 62 Russia under president Putin is trying to reassert itself as a great power to be reckoned with. The annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the continuous meddling in the internal affairs of Eastern European and Caucasian states are serious challenges to the post–Cold War European peace. Russia's cyberattacks on the domestic (election) politics in the United States and elsewhere also disrupt previous norms.Footnote 63 While Russia is not actively promoting an alternative to the LIO, it resembles China in its support for a strictly “Westphalian” order that removes the “liberal” from the existing international order.Footnote 64 Turkey, Iran, and Saudi Arabia are more regional challengers. Last but not least, consider Islamist transnational terrorism. While the Islamic State has been more or less defeated, some Islamists still aspire to a caliphate under which non-Muslims would not enjoy the same rights held by Muslims, a principle clearly at odds with liberalism's principle of universal human equality. Overall, in a serious threat to the LIO, these outside groups and countries have seized this moment of internal challenge to step up their assault on a liberal order they see as denying them the respect and status they deserve.

Finally, the COVID-19 pandemic—which set in after the compilation of this anniversary issue was well underway—certainly constitutes another challenge to the LIO, with potentially far-reaching consequences for the livelihoods and the well-being of hundreds of millions of people. At the same time, however, the political reactions to it have been largely predictable. Populist leaders such as Trump, Johnson, Bolsonaro, and Modi first denied the severity of the crisis and then resorted to nationalist responses. IOs such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Monetary Fund responded slowly at first, but then set in motion a global response based on the scientific advice of epistemic communities of virologists and epidemiologists. Regional organizations such as the EU were equally slow initially, but then mobilized €750 billion to mitigate the public health and economic consequences. While some argue that the pandemic will put an end to globalization and the LIO as we know it, others are more sanguine about the potential consequences.Footnote 65

Some external challengers, like China, are actors with agency. Other challenges, such as COVID-19, are nonagentic forces. However, what they have in common from the perspective of the LIO is that they force members of the LIO to decide whether they will respond in ways that reinforce the order or undermine it. Will core members of the LIO cooperate to further integrate China into the LIO and confront it as necessary, or will they fail to do so? Will they cooperate to rapidly respond to a global pandemic, or will they compete with or free-ride on one another, undermining institutions such as the WHO?

Undermining Multilateral Institutions

These internal and external threats come together in a major challenge to the principle of multilateralism and to core multilateral institutions of the LIO. Core multilateral IOs have certainly been the target of threats before. In 1971, the Nixon administration severed the link between the US dollar and gold, bringing a sudden end to the Bretton Woods monetary regime. While this move shocked the world, it came in response to a series of crises and what was clearly an unsustainable link between the dollar and gold, raising the real prospect of a run on US gold reserves. Likewise, the administration of President George W. Bush first attempted to gain approval from but then broke with the United Nations when member countries failed to back the war in Iraq. Skepticism toward multilateral institutions has a long history among US conservatives, especially within the Republican Party.Footnote 66 Yet, threats to multilateralism appear to be growing, not only from within the United States but also from other countries. Brexit is but one example. Moreover, there is a collective assault on the international refugee regime established after World War II, undermining the nonrefoulement principle.Footnote 67 Most recently, many countries have not only failed to coordinate their responses to the COVID-19 pandemic but have closed their borders, used the pandemic to justify xenophobic policies pursued for perhaps other reasons (like the United States closing its border with Mexico), and attempted to manipulate research and the production of medicines to give their citizens privileged access. While the WHO has attempted to provide leadership, the Trump administration announced that it would cease funding and sever ties with the organization, though the Biden administration has reversed the move.

One of the global institutions that may be most in jeopardy today is the WTO. While the WTO has long been handicapped in its ability to drive major new global trade deals, it has continued to function as the foundation of the global trading system through maintenance of existing agreements and their enforcement through its dispute settlement mechanism (DSM). Under the Trump administration, the United States took aim at the WTO in two main ways. The first was old-fashioned protectionism, with the United States imposing substantial tariffs on many of its major trading partners, prompting a series of trade wars. Perhaps even more challenging for the future of the WTO, however, the United States imperiled the DSM's ability to function by blocking the appointment of trade judges to its appellate body.Footnote 68 Driven by no particular crisis, this is a clear example of a voluntary attack on a core multilateral institution.Footnote 69 And no significant constituency has risen to defend the WTO, even from the internationally oriented businesses that have been its primary beneficiaries.

In addition, under President Trump, the United States withdrew from the Paris Agreement on climate change, withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action related to Iran's nuclear program, withdrew from the UN Human Rights Council, walked away from the UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees (and cut overall funding to the Palestinian Authority), pulled US troops from Syria without prior consultation with its allies and partners, and abandoned the Intermediate Range Nuclear Forces Treaty as well as other arms-control agreements. Regardless of whether the new administration of President Joseph Biden will reverse these moves, the commitment of the United States to multilateralism is not guaranteed. Other countries must at least consider the possibility that the United States will withdraw further from multilateralism in the future. This US-led assault on existing multilateral institutions may be opening the door to other challenges to international cooperation.

Sources of Resilience

Despite these challenges, there are at least four sources of resilience within the LIO. First, it has been remarkably successful in reducing international conflict and global poverty, creating a broad consensus in favor of sustaining this order. As noted earlier, the LIO has contributed to unprecedented levels of international cooperation, most remarkably in collective security as well as trade and finance. The beneficiaries of this cooperation have a continuing interest in sustaining the order. This does not mean that there will not be hard bargaining and tough negotiations in response to changed circumstances. However, overall, the benefits produced by the LIO create continuing support for the basic architecture of the order.

Second, and more specifically, the LIO has created vested interests in the current rules of the political game, especially on the economic side, that will act to protect those rules. The US–China trade war and the global economic convulsion following the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus demonstrate just how interconnected the international economy has become through the disaggregation of global value chains. Many firms now have complex investments across the globe that also create complex political interests, making it ever harder to decide who is “us.” But these same firms have strong interests in sustaining international openness to reap the value of their past investments. Moreover, while the US onslaught on the WTO has not met with much resistance, the Trump administration was completely isolated globally when it withdrew from the Paris Agreement on climate change and cut ties to the WHO.

Third, the LIO has been institutionalized in various IOs, regimes, and treaties, and these institutions are forces for continuity. Institutions are often described as “sticky.” Once formed, they can persist even in the face of exogenous or endogenous change.Footnote 70 In the short run, international institutions can act as “shock absorbers” to cushion events like the Great Recession.Footnote 71 This suggests that even if the LIO becomes less robust given its current challenges, elements will persist for some substantial period. NATO's resilience since the end of the Cold War is, perhaps, the best example.Footnote 72 Fourth, and related, the LIO has over time acquired a measure of international legitimacy or “rightfulness” that bolsters support across publics in at least OECD countries but likely beyond. After several generations of success, and reflecting the underlying political values that supported its rise, the LIO has acquired a normative quality that will, as March and Olson famously suggested in the fiftieth-anniversary issue of IO, mitigate logics of consequences and promote logics of appropriateness.Footnote 73

All of these sources of resilience suggest there may be some countermobilization that helps preserve the LIO or at least some of its more broadly accepted parts. There are undoubtedly serious challenges to the LIO as currently constituted. It is tempting and sometimes too easy in periods of instability and change to raise the cry and shout, “The sky is falling!” But we should also be attentive to the sources of persistence in the LIO such that we may, in fact, be celebrating at the hundredth anniversary of IO.

Analytic Lessons

Why did the field of IR, and especially the scholars whose work has appeared in the pages of IO, not anticipate better the current challenges to the LIO? Regardless of whether the LIO persists in something close to its current form, changes radically, or collapses completely, what do these unanticipated challenges imply for the future research agenda of the field? There were, in our view, at least four analytic “blind spots” that impeded the collective vision of the field. Highlighting these blind spots will, hopefully, allow us to see better than in the past.

First, orders are clubs that include as well as exclude. Although the LIO was “open” in the sense that any state willing to follow the rules could join, it was not universal in practice. The Eastern bloc during the Cold War was excluded, obviously, as well as much of the developing world, embodied in the Non-Aligned Movement and the G-77's call for the NIEO. The challenges to the LIO, however, suggest that it may have also been intentionally exclusionary in ways that generated a backlash to that order.

To be inside any order means to accept and follow the rules set by the states that are members of the existing club. This is seen most clearly in the accession agreements that brought the former communist states in Eastern Europe into the EU. In joining, they had to agree to the acquis communautaire, formulated and accepted by the existing member states. Less formally, membership in the LIO also required the acceptance of certain rules embodied in the Bretton Woods Institutions, NATO, the G-7, and so on. This separates insiders from outsiders, or conformists from nonconformists. To the extent that there are material, status, or other benefits from membership, it is the possibility of exclusion or expulsion that creates incentives for states to follow the rules.

States excluded from dominant international orders, in turn, are perceived by insiders as deficient, either holding values considered inferior or lacking the capacity to participate in “civilized” society. They are, in short, stigmatized and consigned to a lower status.Footnote 74 States attempting to conform to the LIO, in turn, can face a difficult path. They perceive standards of order as dynamic and rising over time, suggesting that at least some states are chasing an ever-receding horizon. What it means to be fully democratic has expanded over time as more states have met previous levels.Footnote 75 This might be a normatively positive outcome, but it has the effect of excluding countries that have made sincere but only limited progress toward democracy. Likewise, standards for human rights practices and for certifying elections as “free and fair” have risen over time, making it harder and harder for states to join the club of insiders.Footnote 76

Any international order without the possibility of excluding violators from its benefits is a weak order. In turn, raising the bar for membership is a principal way of eliciting improved behavior from members. Yet, as clubs continue to exclude, not only can stigmatized states challenge the order but so can frustrated aspirants, creating an oppositional coalition of outsiders. In this issue, Tourinho and Búzás both demonstrate how inequalities were produced and reproduced in “developing” and racially stigmatized states under the LIO.Footnote 77 Adler-Nissen and Zarakol, Adler and Drieschova, and Farrell and Newman examine how excluded states are today challenging the LIO.Footnote 78 In a dialectical fashion, the very mechanism of exclusion central to enforcing international order creates the seeds of challenges to that order.

Second, international orders are not neutral but embody a set of material, ideational, and normative interests congealed into institutions and practices. The adjective “liberal” is an important signifier of the postwar order, with rules favoring those countries (and groups within countries) that supported the free movement of goods and capital, as well as democracy, and championed political and civil freedoms as universal human rights. Yet, many scholars publishing in IO did not fully recognize this bias in the LIO; they did not ignore it, but too easily skipped over it. Institutions were conceived primarily as facilitators of cooperation, and norms were understood as inherently moral or “good,” at least by their adherents. Recognizing that rules are always written by someone for some purpose, most often by then-powerful states to control the behavior of others, helps explain why the LIO in particular has always been contested and is today under serious challenge.Footnote 79

Orders that take hold and endure without frequent coercion must be Pareto-improving. This was the great insight of the cooperation literature and certainly the neoliberal institutionalist school.Footnote 80 By increasing welfare relative to some status quo, actors using reciprocity or creating institutions could render cooperation self-enforcing. The baseline, however, is important. Is the alternative to the LIO a Hobbesian state of nature, a stable and existing international order, or a utopia? The LIO benefited (in a perverse way) from two major world wars that approximated a brutal state of nature. Over time, however, as the LIO became normalized—itself a new baseline—alternatives became more attractive. This is exemplified in Brexit, in which many Britons voting in the referendum erroneously imagined they could retain all the advantages of trading with the EU while “repatriating” their sovereignty from Brussels. The final exit agreement confirmed that this was an illusion.

A similar conception of order animated the constructivist literature. When norms diffuse, the interests of actors are transformed and, at an extreme, internalized such that norm-violating behaviors are rendered literally inconceivable.Footnote 81 In this way, norms both constitute the order and discipline practice in ways consistent with that order, creating a self-enforcing normative society and thus stigmatizing norm violators.Footnote 82 When norms are broadly shared, as they are almost by definition, they take on a moral character. “Good” countries comply with socially constituted and accepted rules. But this inherently moral character of norms has blinded some to the bias in those norms, reflected most clearly in the tension between the individualist and communitarian principles in the UN's Universal Declaration of Human Rights and various calls for respecting “Asian values.”Footnote 83

Both of these literatures tended to minimize the distributional consequences of orders, and especially the LIO. After 1945, the United States projected its domestically defined interests in private enterprise, free trade, democracy, and liberal values onto the emerging LIO. In doing so, it was pushing on an open door in Europe and Japan, where previous domestic interests were destroyed by the war itself and delegitimated by loss and violence. But, as Tourinho as well as Adler-Nissen and Zarakol remind us, there was considerable pushback from countries outside the North Atlantic region.Footnote 84 Perhaps our own liberal blinders as mostly Western scholars publishing in IO led to a tendency to think of cooperation and norms as inherently good—ends in themselves—without recognizing that the sets of policies and practices that constitute cooperation and normative practices will almost always have unequal consequences for different countries and for groups within those countries.

There are, of course, exceptions to our claim that scholars of international relations have minimized the distributional consequences of orders. Theories of open-economy politics certainly emphasized the distributional consequences of economic policies within countries—identifying winners and losers from trade and financial flows. The backlash to globalization is rooted in these distributional effects.Footnote 85 Recognizing that individuals are more complicated than their material interests alone, newer work in this vein examines sociotropic preferences and interacts economic position with identity and status concerns. Research continues on “embedded” mechanisms that might soften the blows of globalization.Footnote 86 But throughout this literature it was accepted that liberal economic policies were welfare-improving for the country as a whole, and thus in both theory and practice any compensation scheme was strictly limited to internal redistribution.Footnote 87

Other writers identified important international implications of and challenges to the LIO. Dependency and world systems theorists were early critics of economic liberalism.Footnote 88 In a powerful analysis, Krasner showed how life on the Pareto frontier could promote cooperation while still being fraught with distributional bargaining.Footnote 89 Similarly, Fearon demonstrated how iteration, which made cooperation more enforceable, could also undermine cooperation by raising the stakes of bargaining.Footnote 90 And, of course, critical theorists and especially feminist scholars were well aware of the biases inherent in the LIO.Footnote 91

These were and remain important exceptions. But the field as a whole—especially as reflected in the pages of IO—did not incorporate these insights into its core research agenda. On the rationalist side, for instance, the literatures on legalization and the rational design of institutions continued to focus on cooperation and emphasized the role of rules in promoting welfare-improving outcomes.Footnote 92 Although the constructivist literature took seriously the critique that sometimes norms are “bad,” at least in retrospect, scholars mostly sidestepped the question of whether any current norms on, say, human rights were inherently biased. Although the Bangkok Declaration of 1993 affirmed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the largely Asian signatories stressed sovereignty and noninterference and emphasized the right to economic development over civil and political rights. The mantle of “Asian values” has now been taken up by China as an alternative to liberalism. The presence of this alternative foundation highlights the limited nature of liberalism despite its claim to universalism—and the same bias in our academic research.

Third, institutions are social constructs that rest on social foundations. As the prior two points make clear, institutions do not stand apart from their societies. Indeed, they become “institutions” (long-lived entities) only when they accord with perceived social interests and norms. Although rules and practices can become legitimated over time by custom and conformance with broader social principles, institutions require social groups willing to expend political capital and energy to construct them in the first place and then defend them against opponents.Footnote 93 As a field, we have always known this at some level, but at the same time we tend to treat institutions as exogenous or at least “sticky” in ways that allow them to stand apart from societal interests.Footnote 94 The challenges to the LIO remind us of the deep relationship between institutions and society.

At the same time, and in a way not sufficiently appreciated in the existing literature, social interests are dynamic and shaped by institutions as sets of rules and practices. Norms and ideas have a similar effect over time, conditioning what is socially appropriate or even permissible to do, say, or even think. Yet, the relationship between society and institutions is complex. Early on, before social groups are sufficiently vested in sets of rules, policy change may require that institutions be designed so that they are insulated from social pressure. As Goldstein and Gulotty argue, free trade offers an important example.Footnote 95 According to Börzel and Zürn, a similar strategy and neoliberal institutions emerged in various global governance institutions, shielding them from domestic interests in the LIO's member states.Footnote 96 In these cases, institutions lost their social footing and, though gaining protectors from among the beneficiaries of globalization, became less responsive to the concerns and plights of the losers from free and open markets. In a second, almost dialectical logic, the nonliberal institutions necessary for economic liberalism, at least, appear to have created their own opponents ready to tear down the pillars of the LIO. The broader lesson, though, is that institutions are robust only so long as they retain, on practical or normative grounds, the support of powerful groups in society.

Fourth, though it might seem ironic given the considerable attention shown to domestic politics in our collective research agenda, domestic politics matter for the LIO. Domestic politics has an established place in the version of IR represented in IO. Studies regularly include variables such as regime type, domestic organization of special interests, and the economic interests of domestic actors. Yet, these studies have mostly focused on how domestic orders affect war, peace, and international cooperation (e.g., the literature on the “democratic peace” and on security communities) or how domestic coalitions affect international trade and finance regimes. Most studies in IR have never considered the possibility that domestic forces in core states would fundamentally challenge the LIO. Such challenges were mostly theorized as emanating from systemic shifts in the international order, such as the end of the Cold War or the loss of a hegemon willing and able to sustain the order.Footnote 97 Studies of the LIO have not drawn extensively on elements of the comparative politics literature that studied political parties, political realignments, or “contentious politics” more generally.

Serious analyses of protests, riots, or rallies organized against elements of the LIO have largely been relegated to comparative politics journals, only occasionally appearing in major IR journals such as IO.Footnote 98 Where is the analysis of how dominant political parties react to what seemed to be fringe elements, and how this reaction leads to fundamentally destructive outcomes like Brexit? In the context of the United States, popular movements such as Black Lives Matter interact with antagonistic right-wing popular movements as these groups feed off one another. Clashes between these protest movements dominate the news and, in an unanticipated way, have posed a fundamental threat to the LIO in their effect on electoral politics. Though colleagues in comparative politics have long studied these questions, theory as represented by the premier IR journal has almost entirely missed these developments and, worse, has no language with which to interpret them—except, maybe, for the work on transnational social movements.Footnote 99

We often rewrite history and our theories of international politics in light of current developments. The Vietnam War shattered the myth of the “national interest” and set off a decade or more of productive theorizing on bureaucratic politics, interest group politics, and psychological models of decision making. The growth of economic interdependence led to neoliberal institutionalism and open-economy politics. The end of the Cold War gave a boost to constructivist theories of international politics. In light of the challenges we now face, the history of the LIO as well as our theories of international politics will—once again—need to be re-examined and possibly rewritten. It is through confronting theory with unanticipated developments and changing practice that we make progress.

Conclusion

Although we would not call it a blind spot in academic research, we conclude here with an open question on the role of the United States in the formation and maintenance of the LIO.Footnote 100 As noted, the role of the United States in building international order was first emphasized in the 1970s. Surprisingly, there was little theoretical attention to this question during the country's heyday; it was taken as natural and largely unquestioned. As US hegemony began to erode, however, its importance became more evident, and its decline was predicted by some to be a precursor to a second Great Depression and closure of the international economy.Footnote 101 When the international economy did not collapse, attention turned to the importance of international institutions as supports for the LIO.Footnote 102 With the end of the Cold War and the emergence of unipolarity, some scholars returned to the idea that the United States was critical to the success of the LIO,Footnote 103 but others extended the neoliberal institutionalist program to argue that the LIO had taken on a life of its own through global governance and the rise of a global civil society sufficient to sustain and even extend its fundamental character regardless of the United States.

The challenges to the LIO we discussed reopen the debate about the United States as a core stakeholder and leader of the LIO's fundamental principles and its significance for the survival of that order. Tourinho deconstructs the myth of US leadership in the construction of the postwar LIO and demonstrates that even middle powers, and especially Latin American states, played a key role in the formulation of the Westphalian and liberal international orders. In short, he shows that it was “not all about the US.”Footnote 104 This offers perhaps a note of optimism. If the creation of the LIO was a more complex process than sometimes acknowledged, and the United States was less central than some believe, then the demise of US leadership may not mean the end of order.

The real—both academic and political—question before us is, then, what will be the outcome of the multiple challenges to the LIO from inside its core members, from rising powers and nonstate violent actors, and from nonagentic forces such as climate change and pandemics. Will the LIO survive the various onslaughts because of other—old and new—stakeholders, as various institutionalist theories that have dominated the pages of IO for decades would predict? Will the LIO gradually disappear, giving rise to the renaissance of an old-fashioned “Westphalian” order based on sovereignty as its key principle, as neorealism would argue? Or will we see the transformation of the LIO into a new international order that preserves some of its principles (economic liberalism, principled multilateralism), while transforming others (rule of law, human rights, democracy)? The research agenda is wide open. It is both normative and analytical. We hope that by addressing the blind spots we have identified, the articles in this special issue will propel this research agenda forward.

Acknowledgments

We thank Anne Jamison for excellent research assistance and the authors in this issue, along with Erik Voeten, Ken Scheve, Jeff Checkel, Peter Katzenstein, and four reviewers, for helpful comments. We also thank the participants of the two workshops preparing the special issue, at the University of Wisconsin–Madison on 6–18 September 2018, and at the Freie Universität Berlin, 12–14 June 2019.

Funding

We are grateful for the funding of these workshops by the Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and by the Cluster of Excellence “Contestations of the Liberal Script” (SCRIPTS), grant EXC 2055 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation).