INTRODUCTION

Sixteen days after the start of the 2006 Israel-Hezbollah War,Footnote 1 which resulted in over 1,100 casualties in Lebanon,Footnote 2 Naveed Afzal Haq forced his way into Seattle's Jewish Federation building armed with two semi-automatic handguns and began firing. According to survivors of the attack, Haq expressed his anger toward Israeli behavior in the Middle East before shooting at Federation employees. By the time the incident concluded, five Jewish women suffered from non-fatal gunshot injuries, and another died as a result of being shot in the head.Footnote 3

While this attack shocked and terrified many in Seattle, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) determined that this shooting did not constitute an act of terror. However, authorities did simply not lump this incident in with other violent crimes that befell the city. Instead, Seattle police and the FBI classified this event as a hate crime based on Haq's purposeful selection of his victims because of their religion. While this attack is one of the more infamous anti-Semitic incidents to have occurred in the United States over the last two decades, it represents just one of 12,400 anti-Semitic hate crimes reported to the FBI from 2001 to 2014.

Analysis of how Israeli military operations affect reported anti-Semitic hate crimes in the United States is valuable to a wide range of scholars and practitioners. It is particularly relevant because of the large size of American Jewry. For roughly 60 years following the horrors of the Holocaust, America became home to the largest concentration of Jews in the world. While dependent on how one defines who is identified as Jewish, the U.S. Jewish population has been only recently surpassed by Israel between the years of 2000 and 2010 (DellaPergola Reference DellaPergola, Dashefsky and Sheskin2015).Footnote 4 Today the United States is home to just under 6 million Jews, which make up more than 70% of the Jewish diaspora population: the total world Jewish population not living in Israel. Moreover, the U.S. Jewish population is 12 times larger than the second largest diaspora community, which is currently located in France (DellaPergola Reference DellaPergola, Dashefsky and Sheskin2015). Consequently, any study of anti-Semitism and anti-Semitic hate crime in the United States is of great benefit for scholars interested in understanding anti-Semitism and the Jewish experience broadly. Combined with more extant anti-Semitism research already focused on European Jewry, this paper helps to provide scholars a more comprehensive view of the global Jewish experience.

Of additional importance is the proportional overrepresentation of anti-Semitic incidents in the totality of all reported hate crime within the United States. According to the FBI Universal Crime Report (UCR) data from 2001 to 2014, when factoring in the size of American religious group's population, Jews have suffered proportionally more reported hate crimes than any other religious group. The only year another religious group's reported hate crime nearly reached parity with anti-Semitic motivations was 2001, which saw a massive spike of anti-Islamic incidents, possibly attributable to the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Perhaps most surprisingly, according to the UCR data, when factoring in the size of group populations, Jews and Jewish institutions have proportionally suffered more hate crimes than Blacks and Black institutions in the United States.

Despite the fact that American Jewry has been targeted so frequently, representing the plurality of all religion-motivated hate crimes in the United States since the FBI started systematically recording these incidents, there is a dearth of scholarship on what motivates anti-Semitic hate crimes and why these crimes fluctuate considerably in both frequency and intensity within states. This paper contends that a key explanatory factor grossly underexplored by scholars is the connection of homeland behavior with diaspora community security. For political scientists, this can partially be accounted for by the two distinct forms in which the study of conflict takes place: the study of interstate conflict and the study of intrastate conflict. Problematically, targets and casualties related to violent military conflicts, although not inflicted by the belligerents themselves, need not occur inside the borders of a warring nation or interstate dyad. Consequently, this paper explores this critical puzzle resulting from current gaps in the political science literature: how does violent homeland conflict engagement affect a diaspora community's insecurity?

This paper proceeds by reviewing the diaspora, anti-Semitism, and hate crime literature. It continues by theorizing why American Jewry specifically as well as the Jewish diaspora broadly is more likely to be targeted as a result of violent Israeli military engagements. It follows by utilizing several fixed-effects negative binomial models to determine how conflict casualties associated with Israeli operations affect the likelihood of reported anti-Semitic hate crime at the state level across the United States from 2001 to 2014. It closes with a discussion of the paper's findings and an exploration of ideas for future research on testing the security implication of the homeland-diaspora nexus, with a particular focus on what additional approaches could advance the study of religion-motivated violence.

DIASPORA

Scholars have argued that diaspora communities can be classified as either active or passive actors in international politics (Shain and Barth Reference Shain and Barth2003). Active involvement occurs when diaspora communities organize with the purpose of influencing the foreign policies of their host-state(s), a phenomenon frequently witnessed in powerful liberal-democratic societies (Patterson Reference Patterson2006). Additionally, diaspora can influence their homeland without any direct support from their state of residence. They can send back money (known as remittances), technology (in the case of conflict, often arms), and even recruits (“return” migration, especially to serve in violent activities during armed conflict) to support their homeland broadly or specific actors operating within it (Collier and Hoeffler Reference Collier and Hoeffler2004). Furthermore, diaspora participation in post-conflict political campaigning and peacebuilding can directly contribute to the likelihood of conflict recurrence (Baser and Swain Reference Baser and Swain2008).

However, not all diaspora communities take on active roles in engaging with their homeland. Sheffer (Reference Sheffer1996) and Shain and Barth (Reference Shain and Barth2003) note that “passive” diaspora can reflect an unsolicited political use of their community by their homeland or describe the targeting of diaspora as unsought representatives of their homeland. They provide two valuable examples of passive diaspora. First, they account for the use of Russian diaspora by the Russian Federation to influence “newly independent non-Russian successor states” (Shain and Barth Reference Shain and Barth2003, 453). Second, they discuss when “diasporas cannot control their status as perceived members of a remote homeland, and thus become implicated in the homeland's international affairs” (Shain and Barth Reference Shain and Barth2003, 453). I argue that this component of their passive diaspora definition is critical to explaining variation in anti-Semitic incidents targeting American Jewry within the United States. However, to simply classify American Jewry as a passive diaspora actor, considering its many active characteristics and real connections to Israel, is insufficient.

At the individual level, American Jews (and non-Jews) have acquired the majority of bonds issued by Israel (Ketkar and Ratha Reference Ketkar and Ratha2010), purchasing over $1 billion bonds annually since 2012, which totals over four-fifths of the total bonds sold each year (Israel Bonds 2017) and is more than representative of its diaspora proportion. Prime Minister Netanyahu has called these bonds “a financial instrument and a fraternal instrument, a bond of brotherhood and sisterhood with the Jewish state” (Israel Bonds 2017). American Jews have also used their political relevance in the United States, particularly their political activism (Patterson Reference Patterson2006), electorally important residential concentrations, and financial resources to successfully lobby on behalf of Israel and the betterment of U.S.–Israel relations through organizations such as The American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) (e.g., Mearsheimer and Walt Reference Mearsheimer and Walt2006; Bard Reference Bard, Eytan and Efraim2008). One of the most important achievements resulting, at least in part, from pro-Israel-motivated political interests and capital include the sustained economic and military aid as well as security cooperation Israel receives from the U.S. government. Despite its small population of roughly 8 million people and its relative wealth compared to other foreign aid recipients, Israel has received more foreign aid than any other country since the 1950s (Patterson Reference Patterson2006). In fact, “since 1962, Israel has accepted more foreign aid from the United States than all of Latin America, the Caribbean, and Sub-Saharan Africa combined (USAID 2002); the combined population of these three areas is well over one billion” (Patterson Reference Patterson2006, 1899). Scholars (e.g., Mearsheimier and Walt Reference Mearsheimer and Walt2006) and politicians on both the right (e.g., Patrick Buchanan) and left (e.g., Ilhan Omar and Rashida Talib) have utilized American aid to Israel as an indictment, claiming American Jewry frequently utilize their political capital and financial resources to serve the interests of Israel at the behest of U.S. interests, foreign and domestic.

It is critical to note that the belief in a pernicious American Jewish influence manipulating American geopolitical positions on Israel and the Middle East is frequently challenged and rejected. In fact, many individuals (e.g., Alan Dershowitz) and organizations (e.g., the ADL) claim that this insinuation of “dual-loyalty” is tantamount to bigotry, utilizing the millennia-old anti-Semitic canard that Jews are a nation within a nation representing their own ingroup above all else. Instead, they point to the shared values of America and Israel as the bedrock for U.S. affinity toward Israel. Additionally, the rise of radical Islamic terrorism combined with Israel's strategic position in the Middle East and their impressive intelligence gathering capabilities, have served to increase Israel's potential in helping the United States seek its regional foreign policy goals.

It is unsurprising, therefore, that administrations, both Democratic and Republican, since Israel's founding, have justified their close relations to Israel through common history, shared economic and security concerns, and as fellow vanguards of democracy. Perhaps this is best articulated by looking at the similarities of speeches between by Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama who shared considerably diverging views on foreign policy. In 2008 President George Bush remarked on arriving in Israel, “We've built strong democracies to protect the freedoms given to us by an Almighty God. We've welcomed immigrants, who have helped us thrive. We've built prosperous economies by rewarding innovation and risk-taking and trade. And we've built an enduring alliance to confront terrorists and tyrants.” Five years later in 2013, President Barak Obama noted while speaking to an Israeli audience in Jerusalem, “Together we share a commitment to security for our citizens and the stability of the Middle East and North Africa. Together, we share a focus on advancing economic growth around the globe…Together, we share a stake in Democracy.”

Still others have argued that the American Jewish community's political support for strong U.S.–Israel ties should be viewed not as lobbying to allow Israel to operate in the Middle East carte blanche, but instead as a reaction to the Holocaust and real concern for the safety of their ethnoreligious kin. Haunted by their inability to better influence the United States to actively protect European Jews targeted by the Nazis during the Holocaust, many American Jews believe powerful and effective lobbying on behalf of an embattled Israel is the only way to live up to the rallying cry of “Never Again” (e.g., Cohen Reference Cohen2002).

Regardless, any charge that American Jewry represents a uniform group committed to serving Israeli geopolitical interests is decidedly problematic for a variety of reasons. First, and perhaps most acute, the sheer size of American Jewry (as compared to both Israel and the rest of the Jewish diaspora) and the geopolitical power of the United States have led to charges that Israel acts on behalf of America, not vice-versa. This position has two origins, one rooted in the unrivaled power of the United States to influence global affairs and the other in the unique size of America's Jewish population.

Second, American Jewry is more heterogeneous and complex than other Jewish diaspora communities. While direct connections to Israel are common among American Jewry, comparative surveys of Jewish diaspora suggest American Jews speak Hebrew less frequently, travel to Israel less often, and hold fewer Zionist attachments and attitudes than any other sizeable diaspora community (Pew Research Center 2013). Scholars suggest that these attitudes and behaviors are undoubtedly related to the successful integration of American Jews into the country's unique pluralistic identity (Chanes Reference Berenbaum2008). Additionally, American Jewry, on average, has suffered far less anti-Semitism—whether state-sanctioned, extra-legal, or criminal—than Jewish diaspora communities in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East (Jaher Reference Berenbaum2008). With the largest period of Jewish emigration from Europe and Eastern Europe to the United States occurring between 1881 and 1924 (Library of Congress 2018), most American Jews avoided the worst of the Holocaust, which systematically destroyed 6 million Jews, roughly two thirds of Europe's Jewish population. This reality is also likely to contribute to variations in attitudes regarding the necessity of a homeland between American Jews and other members of the Jewish diaspora comparatively.Footnote 5

Third, non-Jewish Americans have, by and large, been supportive of Israel throughout U.S. history, and this support has been particularly robust in recent decades.Footnote 6 Although partisan sympathies have become more polarized in recent years, “most Americans (76%) across party lines agree that Israel is a strategic asset to the United States” (Telhami Reference Telhami2016). In fact, the largest pro-Israel organization in the United States is not Jewish but Christian: Christians United for Israel, which boasts over 5 million members (Parke Reference Parke2018). Furthermore, American political leaders, while not always encouraging of specific Israeli behavior, have tended to be extremely sympathetic to its distinctive security concerns. Most U.S. legislation favoring Israel passes in Congress with near unanimity. For example, during Operation Protective Edge in 2014, when Israel was running low on missile interceptors used by the Iron Dome, Congress passed the Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Resolution (H.J.Res.76) providing Israel $225 million in funds. This resolution passed the House 395-8 and the Senate unanimously. Israel also enjoys sweeping support from legislators during periods of considerably greater calm. The United States-Israel Security Assistance Authorization Act of 2018 (S.2497), which details defense and security assistance provisions from the United States to Israel, was passed by voice vote in both the House and Senate. Consequently, attributing the United States’ unique relationship with Israel to specific pro-Israel policies of American Jews alone hazardously undervalues other reasonable and competing explanations.

Despite numerous reasons to assume Israeli conflict behavior should not be directly or fully attributable to the positions of American Jewry, charges that the American Jewish diaspora are defending Israel from what should be greater American scrutiny remains commonplace. However, regardless of one's stance on diaspora culpability for an extremely close U.S.–Israel relationship, there is never a legal justification for the criminal targeting of Jewish Americans and their institutions.

Perceived accountability for homeland behavior becomes more frequent and salient for American Jewry when Israel is engaged in a violent military conflict. Furthermore, these accusations have, at times, invoked imputations that many consider to be anti-Semitic, particularly when they invoke ideas of disproportionate Jewish power in America and/or across the globe. Relatedly, the possession of more traditional anti-Semitic beliefs can also intensify the strength of the perceived diaspora-homeland connection (Kaplan and Small Reference Kaplan and Small2006) and the nefarious motive associated with that connection. The possession of anti-Semitic attitudes and beliefs are likely a precursor, necessary for determining why certain individuals go beyond protected forms of criticism during Israeli military operation, and instead criminally target American Jews and their institutions.

ANTI-SEMITISM

Political science literature interested in anti-Semitism focuses primarily on anti-Semitic attitudes, specifically their origins and characteristics (e.g., Adorno et al. Reference Adorno, Levinson, Frenkel-Brunswik and Sanford1950; Blank and Schmidt Reference Blank and Schmidt2003; Kaplan and Small Reference Kaplan and Small2006; Sheffer Reference Sheffer2012) as part of broader studies on the psychology of intergroup relations. More recently, scholars have attempted to test the effects of anti-Semitic beliefs on behavior (e.g., Kane, Craig, and Wald Reference Kane, Craig and Wald2004; Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Jussim, Harber and Bhasin2009).

Anti-Semitic beliefs share both unique qualities as well as characteristics common in alternative types of intergroup hatred (Bilewicz et al. Reference Bilewicz, Winiewski, Kofta and Wójcik2013, 822). Several studies show that “anti-Semitism correlates closely with xenophobia, Islamophobia, homophobia and the like” (Ambrosewicz-Jacob Reference Ambrosewicz-Jacobs2003; Bergmann and Erb Reference Bergmann, Erb, Richard, Schmidt and Wasmer2003; cited in Bergmann Reference Bergmann2008, 345). Anti-Semitism scholarship, focused almost exclusively in Europe, shows that despite these similarities, anti-Semitic beliefs are often based on distinctive Jewish stereotypes.

Jews are charged with lacking sociability (Lin et al. Reference Lin, Kwan, Cheung and Fiske2005, 35; Bergmann Reference Bergmann2008) thus engendering the belief of extreme group cohesion and exclusivity. This belief contributes to accusation of Jewish diaspora dual-loyalty as well as more grandiose conspiracy theories assuming Jewish control of international finance, business and global governance (Cohn Reference Cohn1967). Belief in an international Jewish conspiracy is also associated with attitudes ascribing Jewish behavior as greedy and dishonest (Brym Reference Brym1996; Krichevsky Reference Krichevsky1999; Bergmann Reference Bergmann2008, 349). Bergmann (Reference Bergmann2008, 349) suggests that “international Jewish power” represent the “dominant” anti-Semitic stereotype, at least in Europe. When employing models of stereotype categorization, such as the ethnic hierarchies model (Hagendoorn Reference Hagendoorn1993) and social dominance theory (Sidanius and Pratto Reference Sidanius and Pratto1999), this belief highlights the uniqueness of anti-Semitism when comparing it to other intergroup animus. Many immigrant minority groups and Roma, for example, do not have the perceived power to dictate influence from the top-down (Bergmann Reference Bergmann2008, 347). The association between Jews and vast power as well as the interrelated charge that Jews lack sociability, can make otherwise predictable and inoffensive diaspora-homeland connections seem far more sinister. These beliefs, especially when activated by a threatening context, can contribute to motivations leading to the criminal targeting of Jews.

A newer research agenda exploring more contemporary forms of anti-Semitism seeks to explain the role Israel plays in the formation and manifestation of explicit anti-Semitic attitudes. Kaplan and Small (Reference Kaplan and Small2006) find that individuals who hold extreme anti-Israel views are more likely to possess anti-Semitic beliefs. Alternatively, Dinnerstein (Reference Dinnerstein2004) argues it is unlikely that Israel represents a truly “new” form of anti-Semitism, and instead represents a new way for pre-existent anti-Semitic narratives to manifest. Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Jussim, Harber and Bhasin2009, 292) find that because classical-bigotryFootnote 7 in contemporary times has largely been forced underground, the use of Israel, the World's only Jewish state, as a proxy for anti-Semitism may be a more “socially acceptable cover for anti-Semitism because other critics of Israel have motives untainted by such bias.” Regardless of whether Jewish associations with Israel epitomize a novel form of anti-Semitism or simply represent a new context for anti-Semitism to be applied, Israel has become central to diaspora concerns regarding the experience of anti-Semitism.

HATE CRIMES

While the diaspora and anti-Semitism literature is helpful in explaining possible motives for targeting American Jewry for Israel's actions, this literature is of limited use in explaining why perpetrators actually engage in the criminal targeting of Jews. Consequently, this paper turns to the emergent literature focused on the systematic study of hate crime to help elucidate why Jews might be targeted for Israeli conflict activities.

Prejudicial subjugation and violence have, in many ways, been woven into the historic fabric of the United States since its first settlers, ironically, many of whom were escaping similar persecution in Europe. However, state-sponsored or endorsed organized violence including the systematic slaughter of Native Americans, the mass enslavement of Blacks, and Jim Crow laws should not be confused with hate crimes.Footnote 8

As a result of the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, protecting civil rights and investigating their violations became a task of the federal government, of which the FBI has played a critical role. It would still take several decades for the term hate crime to become popularized in the United States as a result of media coverage surrounding several prominent incidents targeting Blacks, Jews, and Asians in the 1980s (Green et al. Reference Green, McFalls and Smith2001, 480). Following congressional legislation, the FBI began publishing reported hate crime statistics in the 1990s.Footnote 9

Theories of hate crime tend to emphasize either an objective or subjective approach to incident motivation and manifestation. For example, several scholars (e.g., Pinderhughes Reference Pinderhughes1993; Tolnay and Beck Reference Tolnay and Beck1995) believe hate crime is driven by a threat(s) posed by an outgroup(s).Footnote 10 This outgroup threat can take many tangible forms including the competition of resources (e.g., Sherif et al. Reference Sherif1961), political rivalry (e.g., Kopstein and Wittenberg Reference Kopstein and Wittenberg2018), and national and cultural decay (Holz Reference Holz2001). However, scholars interested in studying threat as a motivation for hate crime need to account for the reality that the perception of threat is often the result of demonstrated and experienced (objective) group concerns intertwined with exaggerated or entirely untruthful narratives and propaganda (subjective). In examining motivations for targeting American Jews and their institutions, it is important to merge the objective and subjective elements underscored in both the diaspora and anti-Semitism literature. Specifically, American Jewry's genuine, exaggerated, and fictitious connections to Israel provide the basis for seeing American Jews as threating and blameworthy. Demonstrable links (or the perception of them) to the Jewish homeland when erroneously weaved into related anti-Semitic narratives and tropes that allude to a broad threat posed by Jews to one's ingroup (be it their own ethnic group, nation, or the entire world) results in Israeli behavior evidencing and enhancing this threat. In short, when Israel, the only professed Jewish nation on earth, is engaged in violent military conflict, the salience of objective and subjective explanations of Jewish threat increases, serving to help actualize the perceived threat associated with Jews broadly and American Jews specifically, in potential perpetrators of their criminal targeting. It is Israeli actions that can turn latent anti-Semitic attitudes into criminal, bigoted behavior.

WHY ISRAEL MATTERS

Building largely from the reviewed diaspora, anti-Semitism, and hate crime literature, this paper hypothesizes that violent Israel military operations will result in spikes of reported anti-Semitic hate crime because they activate latent anti-Semitism in individuals through two distinct but not mutually exclusive mechanisms: (1) confirmation of anti-Semitic attitudes and beliefs and (2) perceptions of direct threat, which induce reactive action. These two dynamics closely mirror two of the three factors Pinderhughes (Reference Pinderhughes1993) argues shapes racial violence in New York City, specifically structural conditions and ethnic and racial attitudes. The first mechanism articulated by this paper focuses on how Israeli military operations act as confirmation bias for certain anti-Semitic beliefs, particularly the belief in a nefarious and disproportionate Jewish influence in both the United States and on global events. As a regional power, Israeli military capabilities have been unmatched by their foes during the armed conflicts they have participated in, particularly over the last four decades. Relatedly, this has allowed Israel to induce extremely high costs on their enemies while enjoying drastically less damage to their own critical infrastructure including suffering far fewer casualties than their foes, both military and civilian. Since the start of the second Lebanon War, militants and populations under their control have suffered casualties at a rate of nearly 20-1 to Israel.Footnote 11 This paper contends that this seemingly Israel-favorable casualty ratio is key in contributing to narratives of Jewish power, and helps to activate latent anti-Semitism and confirm pre-existing anti-Semitic beliefs.Footnote 12

The second mechanism explains how Israeli military operations and resulting violence can induce a sense of threat within individuals not directly participating in the conflict and how these emotions can make action more likely. Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Jussim, Harber and Bhasin2009) find that people who experience stimuli inducing mortality salience are more likely to report anti-Semitic attitudes and are less likely to be supportive of Israel. Images and narratives of extreme violence resulting from Israeli military operations are frequently visible on mainstream news sources as well as on social media during these conflicts. Seeing and reading about death is likely to induce greater mortality salience, thus prompting increases in anti-Semitism and anti-Israel sentiment.

Relatedly, Bradley et al. (Reference Bradley, Codispoti, Cuthbert and Lang2001), utilizing the defense cascade model (Lang, Bradley, and Cuthbert Reference Lang, Bradley and Cuthbert1997), report that pictures of mutilated victims of violence strongly activated a sense of defensive action such as imminent attack within those surveyed. For those susceptible to or already subscribed to narratives of a Jewish-Israeli danger to their individual wellbeing or the security of groups whom they identify with, violence attributed to Israel can move this belief from distant to present, and makes reactive action more likely. This reactive action will directly contribute to the increased targeting of Jews and result in increases of anti-Semitic hate crime.

DATASET SELECTION AND JUSTIFICATION

A major reason behind the paucity of systematic research analyzing hate crimes is concerns surrounding the collection and comparability of hate crime data. Consequently, it is vital to explain the rationale behind choosing the FBI's UCR hate crime data over possible alternatives as well as to explore the limitations of plausible data sources.

Choosing the appropriate data source for analyzing anti-Semitic incidents across the United States for an extended temporal period is currently limited to two major sources: (1) the FBI's UCR hate crime data (UCR) or the collection of the Anti-Defamation League's (ADL) annual audits of anti-Semitism. The UCR dataset provides certain clear advantages over the ADL audits that this paper reviews below.

First, while the UCR data are limited to incidents handled by policing agencies reaching a criminal threshold, the ADL data include both criminal acts and non-criminal acts such as “incidences of written and verbal harassment and intimidation” (ADL 2016). This can be explained by the way data are collected and substantiated by the FBI and ADL. The FBI accepts crime data “from participating law enforcement agencies through the Summary Reporting System or through the National Incident-Based System” (FBI 2019). In order to be considered a hate crime, police investigating a reported crime must arrive at the conclusion it was motivated “in whole or in part, by the offender's bias(es) against a race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender, or gender identity” (FBI 2019). The FBI then aggregates these reported crimes from both aforementioned systems into yearly reports available through the FBI, with partial summaries of available data published in its Hate Crime Statistics publication. Alternatively, the ADL builds its data from the crimes reported in the UCR as well as from reports of anti-Semitic incidents directly to the ADL, which occur when witnesses or victims contact their local office by telephone or by submitting a report of their incident online through the ADL website. After the complaint is received, the ADL investigates the incidents veracity to verify that the incident indeed had an anti-Semitic motivation. Many of the incidents reported exclusively by the ADL do not reach a criminal threshold, including anti-Semitic messaging online, the bullying of Jewish children at schools, or the use of protected anti-Semitic speech by individuals in the public sphere.

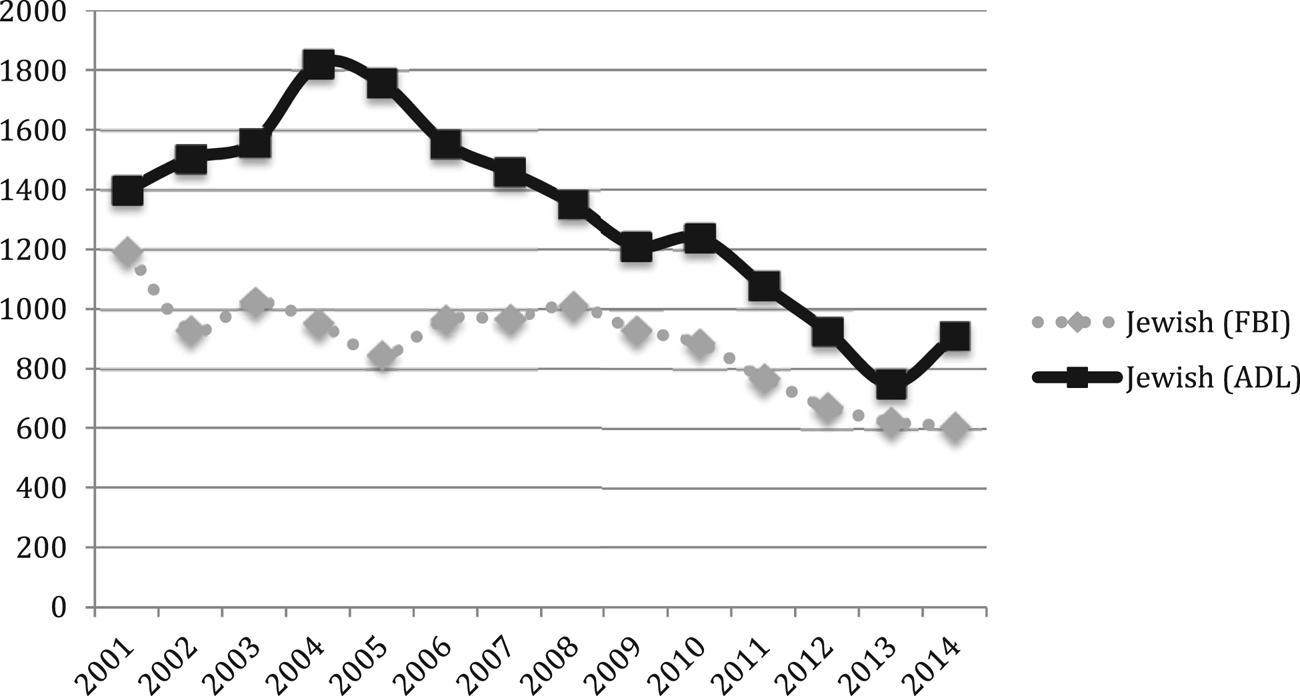

It is unsurprising, therefore, that on average the ADL data annually reported 445 more anti-Semitic incidents than the UCR from 2001 to 2014. This margin peaked in 2005 with the ADL documenting 909 more anti-Semitic incidents than the UCR, the difference actually representing more anti-Semitic incidents than the UCR reported for that entire year. Since 2008 the ADL and UCR data have acquired greater parity, with the ADL reporting only 280 more incidents on average annually. While the UCR data may systematically undercount the total number of anti-Semitic events in the United States, this paper is interested specifically in hate crimes, and the criminal threshold of the UCR data provides this without further disaggregation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Total reported anti-Semitic hate crime by year (comparison of ADL and FBI (UCR) data from 2001 to 2014 (ADL, 2001–2014)).

Also important are concerns of geographic and temporal data quality. This paper's theory and its operationalization require U.S. anti-Semitic incidents be disaggregated at the state level, which is available in both the UCR and ADL data. Temporally, however, the UCR data are vastly superior to the ADL data in that it publicizes the day in which a hate crime incident occurs. The ADL aggregates all incidents that are reported in a state in an annual report, which makes testing certain variables, such as the effect of an Israeli military operation lasting just weeks, particularly challenging. Other control variables, such as the effect of annual Jewish holiday, are simply not testable through the ADL data.

An additional data concern is the level of detail of an anti-Semitic incident description. The ADL provides a total incident count and has disaggregated this count into three categories: (1) “Harassment, Threats, and Events,” (2) “Vandalism,” and (3) assaults. However, in certain years, only the total counts have been reported, while in other years, assaults have not been included in the disaggregation. Alternatively, the UCR data on anti-Semitic incidents have documented over 26 different offense types. The UCR data also have critical descriptive information which often includes the number of victims, type of victim(s), and location details (e.g., bar/nightclub, government/public building, residence/home, etc.). These details can be particularly useful for scholars wishing to analyze more micro-level characteristics of anti-Semitic incidents. Ultimately, due to its temporal flexibility, descriptive capacity, and criminality threshold, my analysis uses the UCR data. In doing so, however, it recognizes some notable shortcomings.

Concerns regarding reporting bias in the UCR data are unavoidable as the participation of law enforcement agencies in reporting hate crime data to the FBI is voluntary. For example, in 2001, non-reporting agencies represented close to 15% of the U.S. population (FBI 2002). Furthermore, certain states such as HI have consistently failed to participate. Other states report zero or close to zero hate crimes in a given year, what some scholars have considered a statistical impossibility (e.g., Ahuja Reference Ahuja2015). Citing the 2015 UCR data, the ADL's current CEO, Jonathan A. Greenblatt, noted, “at least 85 police agencies in cities over 100,000 did not participate in this report--or affirmatively reported that they had zero hate crimes” (ADL 2016). Nonetheless, the number of participating police agencies within a state has not varied considerably across time and is not associated with significant differences in a state's reporting of hate crime.Footnote 13 Furthermore, it should be noted that Jonathan Greenblatt, whose criticism of police reporting is evidenced in the aforementioned quote, recently called the UCR “the most important national snapshot of the hate crime problem in America” (ADL 2016). Despite its concerns, the UCR data represent the best available source for scholars interested in systematically studying ethnoreligious-motivated hate crimes, including incidents specifically targeting Jewish individuals.

DATA AND METHODS

Dependent Variables

The dependent variable for my analysis is the number of anti-Semitic incidents occurring in a U.S. state in a given week. To the best of my knowledge, the research of Jacobs et al. (Reference Jacobs, Veny, Callier, Herman and Descamps2011) represent the only time scholars have used the number of reported anti-Semitic incidents within a country as a dependent variable. Looking at the number of reported anti-Semitic incidents that occurred during Operation Cast Lead in Belgium, Jacobs et al. (Reference Jacobs, Veny, Callier, Herman and Descamps2011) suggest that a weekly count provides the most appropriate temporal unit to study this phenomenon.Footnote 14 Furthermore, the breakdown by state-week allows for the model to control for other variables, such as high-profile Israeli diplomatic visits to the United States, which may also increase the salience of Israel in potential perpetrators similar to significant Israeli military operations.

The count of anti-Semitic incidents in a given week is taken from the FBI's Universal Crime Report (UCR) database. Of the 36,550 weeks covered in my analysis, states report 5,738 weeks where at least one anti-Semitic incident was reported. The mean number of reported anti-Semitic hate crimes by a state in a week is .335. The minimum number of reported anti-Semitic hate crimes states report in a week is 0, and the maximum is 25.

The UCR data report more than just a crime's motivational bias, it also codes the “type” of criminal offense. Beyond utilizing total anti-Semitic incident counts, I aggregate criminal offense types into two categories: (1) vandalism offenses and (2) violent-intimidation offenses. These two aggregated incident groupings make up the vast majority of anti-Semitic offenses coded in the UCR data with vandalism offenses consisting of 5,744 incidents and violent-intimidation offenses consisting of 3,577 incidents. The primary difference between violent-intimidation incidents and vandalism incidents is the type of target. Most violent-intimidation offenses target an individual or group of Jews, while most vandalism offenses target Jewish property or Jewish institutions. This breakdown allows the models to pick up whether Israeli military conflicts have different effects on hate crime type, which is critical for more pragmatic utilization of this analysis.

Independent and Control Variables

To test for the influence of Israeli military operations on anti-Semitic incident variation, this paper codes all weeks in which an Israeli military operation that ultimately results in at least 100 opposition casualties as 1, and all other weeks as 0. The 100-opposition casualty figure coding decision was the result of a natural break in conflict casualty data. There are six Israeli military operations that have met this threshold during 2001–2014: Operation Defensive Shield (2002), Operation Days of Penitence (2004), the Second Lebanon War (2006), Operation Cast Lead (2008–2009), Operation Pillar of Defense (2012), and Operation Protective Edge (2014). These operations span 33 weeks in the dataset. Weeks in which Israel is not engaged in a substantial military operation have resulted, on average, in far fewer casualties, making these operations distinct from lower intensity violence that has long defined Israeli conflicts in Lebanon after its troop pullout in 1999, and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict in both the West Bank and Gaza. All casualty statistics come from commonly cited data collected by Israeli NGO B'Tselem (B'Tselem 2016).

As a control, this paper measures prominent Israeli diplomatic meetings with key U.S. officials in the United States using data from the Office of the Historian, located in the U.S. Department of State (Office of the Historian 2017). Whenever a high-level foreign leader from Israel, most commonly Israel's Prime Ministers visits the United States in a given week, it is coded as 1, and all other weeks as 0. There are 34 of these visits that occur throughout the dataset. This variable is included in the models in order to account for other periods of time in which Israel and American–Israeli relations are more salient.

As an additional control, this paper also utilizes the number of Israeli casualties that have been recorded as a result of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict in a given month, disaggregated to look at Israeli casualties occurring within Israel territory prior to the 1967 Six-Day War and Israeli casualties occurring in the West Bank and Gaza. The casualty statistics utilized are gleaned from data published by Israeli NGO B'Tselem (B'Tselem 2016). Israeli casualties occurring within internationally recognized Israeli territory range from 0 to 75 per month, with an average of just over three casualties from 2001 to 2014. Israeli casualties occurring in the West Bank and Gaza range from 0 to 18 per month, with an average of just under 1.5 casualties from 2001 to 2014.

Lastly, because of the large quantity of observations utilized in this dataset across time, this paper dummies each year (from 2001 to 2014) and month (January–December) in the data to control for their possible unobserved influence on reported anti-Semitic incidents across specific years and months.

Methodology

Because the dependent variable in the analysis is an event count, specifically the number of anti-Semitic incidents per week, the paper employs several negative binomial regression models to analyze variation in anti-Semitic hate crime. Ordinary least squares estimates are inappropriate for these data because there is no possibility of negative incidents, which could lead to estimate bias, inconsistency and inefficiency (Long Reference Long1997). The Poisson regression, often used in event count models, is also an improper model choice because of its restrictive assumption regarding the conditional mean equaling the conditional variance. The negative binomial regression is a more appropriate model selection because it estimates an additional parameter to account for unobserved heterogeneity of event occurrence so conditional variance can exceed the conditional mean (Cameron and Trivedi Reference Cameron and Trivedi2013) as it does in all three of my models.

This paper's models utilize panel data to allow for better control of unobserved or immeasurable factors across states as it accounts for individual heterogeneity. The key reason to utilize fixed effects in these negative binomial models is “because the unobserved variable does not change over time… any changes in the dependent variable must be due to influence other than these fixed characteristics” (Stock and Watson Reference Stock and Watson2003, 289–90). The data in this analysis is grouped at the state level, which is common in social science research examining the United States. Consequently, there are 50 observed groupings, each with 731 weekly observations from 2001 to 2014. The focus on within difference changes in a state is particularly valuable for my models related to reasons concerning consistency in law enforcement agency reporting and possible different criminal thresholds of incidents existent across states.Footnote 15 Additionally, the use of fixed effects helps to alleviate concerns of potential confounding influences that are extremely hard to measure or whose data are unavailable across the temporal period of the study including both the diversity of ethnic and religious groups and heterogeneity of industry at the state level. A considerable number of robustness checks were applied to verify that both the negative binomial regression and fixed effects were the most appropriate choices for my models.Footnote 16

FINDINGS

This paper hypothesized that reported anti-Semitic hate crime would increase in weeks during violent Israeli military operations in America. All three models find that these military operations exert more influence in explaining upsurges in reported anti-Semitic hate crime than any other measured variable. These military operations wield the most influence in explaining rises in reported violent-intimidation anti-Semitic hate crime. These findings suggest that significant Israeli military operations fundamentally explain increased insecurity of American Jewry.

Table 1 reports the findings of three fixed-effects negative binomial regression models, each with a different dependent variable. The left column reports how each independent variable affects the total number of reported anti-Semitic hate crimes in a state per week. The center column specifically details anti-Semitic hate crimes classified as vandalism in a state per-week and the right column accounts anti-Semitic hate crimes coded as incidents of violence or intimidation. All models report findings through incident rate ratios (IRR). The top number that is reported across from each variable is the (IRR), while the bottom number in parentheses is the standard error.

Table 1. Negative binomial regression, fixed effects (U.S. reported anti-Semitic hate crime, 2001–2014)

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

The first model looking at the total number of anti-Semitic hate crimes reported in a state confirms the theoretical expectations of this paper. In weeks when Israel is engaged in a substantial military operation, states are 22.70% more likely to report an anti-Semitic hate crime than weeks when conflict is at a lower intensity. Visits by high-level Israeli leadership to the United States and Israeli casualties in Israel and the West Bank and Gaza resulting from both Israeli military engagements and terror attacks associated with the Israeli–Palestinian conflict have no significant effect on reported anti-Semitic hate crime.

The second model looking at anti-Semitic hate crime classified as vandalism finds that Israeli military engagements continue to have a significant effect on reported incidents. In weeks when Israel is engaged in a military conflict, states are 16.35% more likely to report an anti-Semitic hate crime.Footnote 17 Visits by high-level Israeli leadership to the United States and Israeli casualties in Israel and the West Bank and Gaza resulting from both Israeli military engagements and terror attacks associated with the Israeli–Palestinian conflict continue to have no significant effect on reported anti-Semitic hate crime.

The third model looking at anti-Semitic hate crime classified as violent and intimidation incidents shows that Israeli military engagements have the most robust effects on these types of reported incidents.Footnote 18 In weeks when Israel is engaged in a military conflict, states are 35.74% more likely to report an anti-Semitic hate crime. Again, visits by high-level Israeli leadership to the United States and Israeli casualties in Israel and the West Bank and Gaza resulting from both Israeli military engagements and terror attacks associated with the Israeli–Palestinian conflict have no significant effect on reported anti-Semitic hate crime.

DISCUSSION

The above findings represent a vital first step in the systematic study of how homeland behavior alters diaspora security and explaining how Israeli military operations place American Jewry at an increased likelihood of being the victims of hate crimes. The significant results that Israeli military operations with at least 100 casualties increase the likelihood of a state reporting anti-Semitic incidents is statistically significant across all three models. However, to fully appreciate both the causes and magnitude that Israeli military operations have on diaspora security, it is valuable to also emphasize the insignificance of high-profile Israeli diplomatic visits to the United States and Israeli casualties from military conflicts and terrorism.

First, both intense Israeli military operations and high-profile visits from Israeli Prime Ministers and Presidents to the United States get considerable media coverage. Nonetheless, high-profile visits do not result in a state's increased likelihood of reporting anti-Semitic hate crime across all incident types. The fact that high-profile Israeli diplomatic visits have no significant effect on reported anti-Semitic hate crime suggests that violent behavior attributed to a homeland and diaspora, not just increased salience underscored by their general visibility, plays a key role in whether a diaspora community is more likely to be victimized. Specifically, violence resulting in a large quantity of casualties is necessary in prompting actions that will ultimately lead increased diaspora insecurity.

Second, Israeli casualties resulting from Israeli military operations, and terror attacks associated with the Israeli–Palestinian conflict also have no significant effect on reported anti-Semitic hate crime across all three incident types. This suggests that violence more broadly defined or violence specifically targeting members of the diaspora's homeland will not have a measurable effect on reported hate crime. Instead, these findings serve to underscore that the homeland, and relatedly the diaspora, must be seen as the perpetrator or perpetuators of violence for hate crime against a diaspora community to increase.

The powerful effect that Israeli military operations have on reported anti-Semitic hate crime across all three incident types and the failure of the control variables to register significance evidence that diaspora security is intimately linked to homeland military endeavors that result in considerable opposition casualties. Additionally, the substantive effect of these finding is considerable, particularly when considering its influence on the likelihood of violent anti-Semitic hate crimes. Knowing that a state is nearly 35% more likely to report a violent anti-Semitic hate crime in weeks during Israeli military conflicts should result in serious modification to security procedures within Jewish communities and across Jewish institutions, as well as for related local and state law enforcement.

FUTURE RESEARCH AND CONCLUSION

The significant role Israeli military operations play in increasing the targeting of American Jewry is imperative for scholarship interested in prejudice toward and the security of ethnic minorities, as well as anti-Semitism specifically. This research opens up considerable opportunities for research exploring the current vacuum in the diaspora literature on how homeland behavior and reputation alters diaspora communities, particularly their security, identity, and attitudes.

Future research that is critical to completing our understanding of Israel's role in Jewish diaspora security is empirical analyses accounting for hate crime perpetrator characteristics. However, current data availability makes constructive analysis of an offender's race, ethnicity, and religion extremely challenging, if not infeasible altogether for several reasons. First, while the FBI UCR data do offer space for the official reporting of an offender(s) race, they do not record perpetrator ethnicity or religion. Consequently, any exploration of whether Israeli military operations trigger any specific ethnic, national, or religious populations to target American Jews at higher rates cannot be measured in this paper's models. While several scholars have noted that anti-Zionism, including anti-Israel attitudes that extend into the realm of anti-Semitism, are more frequent among young male Arabs and Muslims in Europe (Wistrich Reference Wistrich2002; Jikeli Reference Jikeli2015a; Reference Jikeli2015b), the UCR data code Middle Eastern and North African offenders as “White” individuals. Additionally, while it is likely that the possession of anti-Semitic attitudes is a necessary precursor for committing an anti-Semitic hate crime, simply possessing anti-Semitic attitudes does not mean an individual will commit a hate crime. Second, roughly 80% of all reported anti-Semitic hate crimes in the United States included in the UCR have no known offender racial data in a given year. This is concerning not only because it prevents analyses that are crucial in advancing the systematic study of hate crime but because it suggests a considerable number of hate crimes go unsolved. This lack of perpetrator characteristics is largely explained by incident type and associated lack of offender certainty. For example, if a synagogue reports that someone spray-painted swastikas on their property, in the absence of any clear videotaped footage or eyewitnesses, there is no way racial, ethnic, or religious identity of the perpetrator can be inferred unless investigations successfully lead to the offender's arrest. Additionally, because crimes of vandalism make up the majority of anti-Semitic hate crimes across the data and these crimes have considerably lower arrest rates, offender data are unsurprisingly limited. Scholars interested in systematically studying perpetrator data associated with minority targeting will likely have to utilize data limited to extremely violent crimes and murders, which have substantially higher arrest rates.

An additional avenue for future scholarship is comparing the effects of Israeli military operations across different diaspora communities, namely those in Europe and North America. Not only do diaspora communities exhibit different intensities and types of connections to their homeland, they will also vary in size, concentration, and even political relevance across countries. Furthermore, nations hosting diaspora populations will have different diplomatic relationships with that group's homeland as well as different security procedures for targeted minorities. What constitutes a hate crime also varies considerably across countries in the West. For example, while denying the Holocaust might constitute an anti-Semitic hate crime in Germany or France, it is not a criminal act in the United States (Lipstadt Reference Lipstadt2012).

While there are limits to universalizing the findings presented in this paper's analysis as it focuses on an individual homeland and corresponding diaspora, this research should provide a critical baseline for scholars seeking to develop a greater understanding of the homeland-diaspora nexus, particularly as it relates to how homeland conflict can affect diaspora insecurity. Specifically, American Jewry's connections to Israel, real, exaggerated and imagined, are critical in explaining when and why they will be the target of hate crimes in the United States.

Appendix

Table A1. Naïve fixed-effects negative binomial regression model (results reported with IRR)

Table A2. Poisson regression model (results reported with IRR)