Although Senator Kamala Harris was an early frontrunner for the Democratic nomination,Footnote 1 she suspended her presidential campaign in December 2019 before the Iowa Caucus. After Harris’s withdrawal, a Vanity Fair piece claimed the campaign’s downfall was the lack of a clear message, arguing that “Harris came off standing for everything, and hence nothing” (Hamby Reference Hamby2019). Indeed, although conventional wisdom may suggest that taking vague rather than clear policy stances can broaden a candidate’s appeal, political science research (e.g., Alesina and Cukierman Reference Alesina and Cukierman1990; Callander and Wilson Reference Callander and Wilson2008; Krupnikov and Ryan Reference Krupnikov and Ryan2017; Piston et al. Reference Piston, Krupnikov, Milita and Ryan2018; Shepsle Reference Shepsle1972; Tomz and Van Houweling Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2009) has shown that the effectiveness of ambiguity should be conditional on a number of factors. Thus, I took advantage of an original survey fielded early in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary to apply insights of the growing literature to this real-world example. Specifically, I tested how ambiguity in Harris’s position on healthcare impacted both her support and her favorability. I found that ambiguity offers little advantage and that it actually harmed her among those voters most strongly inclined to favor a move toward a government-run insurance plan. Although somewhat surprising given that clarity often is touted as the more dangerous strategy, these findings are consistent with works highlighting the conditional nature of the effects of ambiguity and they offer new evidence to this research.

AMBIGUITY IN THEORY

Ambiguity should make candidates appealing to those with a larger range of opinions and avoid highlighting gaps between their own beliefs and those held by voters. For example, if a candidate claims that she supports mandatory gun-buyback programs, then voters should easily determine whether they agree with that position and reward or penalize her accordingly. However, if that same candidate instead only states that she favors commonsense gun legislation, it should be more difficult for voters to assess their agreement with her because what exactly constitutes “commonsense” is open to interpretation. In the absence of concrete information that the candidate does not agree with the voters’ own positions, they should be more likely to project their own opinions onto the candidate (Jensen Reference Jensen2009). Thus, ambiguity potentially can aid candidates by allowing them to appear aligned with a greater number of voters.

However, the advantages of ambiguity are not absolute. First, the success of ambiguous rhetoric should be conditional on the risk acceptance of the electorate (Shepsle Reference Shepsle1972). Returning to the gun-policy example, if the candidate makes the clear statement, then voters should be fairly confident in their belief that she will support any buyback legislation. But if the candidate has made only the ambiguous statement, then there should be more uncertainty about how she would vote on such a policy. Risk-accepting voters may be comfortable with the gamble that ambiguity presents because there is potential for a favorable outcome. In contrast, risk-averse voters may dislike the risk and instead prefer a candidate whose position is more certain—even if that position is counter to their own (Morgenstern and Zechmeister Reference Morgenstern and Zechmeister2001).

However, to say that risk-averse voters will always prefer certainty and the risk-accepting voters will always prefer ambiguity is an oversimplification. Preferences also will be related to the favorability of the more certain alternative. When the more certain option is perfectly aligned with a voter’s own preferences, then even the most risk-acceptant voter should prefer certainty. In these cases, “the voter cannot gain and may in fact lose by selecting the risky candidate” (Tomz and Van Houweling Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2009, 84). Furthermore, individuals higher in risk aversion also display status quo bias (Kam and Simas Reference Kam and Simas2012). Because departures from the status quo typically involve moving toward a new and unknown outcome, they also come with some risk. Moreover, whereas in some cases a departure from the status quo also will be the more uncertain outcome, the two may not necessarily align. Even when a candidate takes a clear position, that position still may be perceived as risky if it involves a certain change from the policies that are currently in place. In these instances, a risk-averse voter actually may prefer ambiguity because a stance that offers at least some probability of maintaining the status quo may be more attractive than guaranteed movement away from the current norm. In summary, explorations of the relationship between ambiguity and risk acceptance need to consider the relative attractiveness of the more certain option.

When the more certain option is perfectly aligned with a voter’s own preferences, then even the most risk-acceptant voter should prefer certainty.

Second, the effects of ambiguity also should be contingent on the partisan context. Because voters have a tendency to assume that candidates share the positions of their party, ambiguous statements may not be perceived any differently than clear statements when party labels are present (Milita et al. Reference Milita, Simas, Ryan and Krupnikov2017; Tomz and Van Houweling Reference Tomz and Van Houweling2009). At a minimum, party brands should limit the range of plausible positions that an ambiguous partisan candidate may take such that an ambiguous Democrat (Republican) can be assumed most likely to support a selection of more liberal (conservative) policies and highly unlikely to vote for more conservative (liberal) options. Thus, particularly when the two parties are polarized, opposing party labels should help reduce the riskiness associated with supporting an ambiguous candidate. The resulting implication is that ambiguity and risk acceptance should play less of a role in general elections and have a more significant effect in primaries, where party labels do not distinguish among candidates.

CONNECTING THEORY TO THE 2020 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION

During the second night of the first round of Democratic presidential primary debates, Senator Kamala Harris was one of only two candidates to indicate that she would abolish private health insurance. However, in a televised interview the next day, Harris backtracked, stating that she had misunderstood the question (Gregorian, Sarlin, and Hillyard Reference Gregorian, Sarlin and Hillyard2019). This was not the first time that Harris’s position was muddled (Sarlin Reference Sarlin2019), and even after releasing a plan for a gradual transition away from private insurance, she continued to be attacked for “straddling the fence” (Lah, Luhby, and Krieg Reference Lah, Luhby and Krieg2019). In contrast, many of Harris’s opponents staked out decidedly clear positions. In particular, former Vice President Joseph Biden strongly advocated for maintaining options for private insurance, whereas Senator Elizabeth Warren championed abolishing private insurance in favor of Medicare for All. Altogether, Harris’s ambiguity and differences among these three candidates allowed for a real-world test of the impact of these various positions.

Applying theory to this example, a clear statement in favor of government-run health insurance should be viewed as a relatively risky option because it represents the biggest departure from the status quo. An ambiguous statement, although less certain, at least introduces the possibility of maintaining the status quo. Thus, risk-acceptant voters should prefer Harris when her position is clear versus when it is ambiguous. This should be particularly true among those who favor government-run insurance because ambiguity in this case is a gamble against, not in favor of, their preferences. However, for risk-averse voters, ambiguity versus being clearly against private insurance should enhance Harris’s attractiveness. Again, this should be related to individuals’ preferences, with the strongest effects of rhetoric being apparent among those voters who are risk averse and who also oppose a government-run plan.

Thus, risk-acceptant voters should prefer Harris when her position is clear versus when it is ambiguous. This should be particularly true among those who favor government-run insurance because ambiguity in this case is a gamble against, not in favor of, their preferences.

I expected that these differences would be apparent when examining preferences for Democratic primary candidates. However, when comparing Harris to Trump, I expected little to no effect. As Andy Slavitt, a former Obama administrator, noted, “What you’re talking about here is sky blue versus powder blue whereas Trump is blaring grey” (Lah, Luhby, and Krieg Reference Lah, Luhby and Krieg2019). In other words, ambiguity may make Harris more or less risky when compared to fellow Democrats, but whether or not her position is clear, it almost certainly represents a departure from the incumbent Trump administration. As such, preferences for Harris versus Trump should turn more on partisanship and issue opinions rather than the clarity of Harris’s position.

METHODS

My experimental test was embedded within a larger survey completed by 2,024 US adults in September 2019. The sample was drawn from Lucid, an online panel provider that uses quota sampling to match US Census demographic margins. Although not a random sample, Lucid’s extremely large pool of subjects allows for samples that tend to be more reflective of population benchmarks than those drawn from other platforms (e.g., Amazon’s Mechanical Turk) and it allays some concerns about subject professionalism. Moreover, researchers have used Lucid to replicate the findings of experiments conducted using a variety of samples and platforms (Coppock and McClellan Reference Coppock and McClellan2019). To be sure, my sample demographics are similar to those from the 2016 American National Election Study (see the online appendix) and, as discussed herein, opinions from this sample align with national polling from around the time of administration.

The experimental treatments present information about the healthcare positions taken by Harris, Biden, and Warren. Although this greatly simplifies the actual electoral context—there were 21 candidates at the time the survey was launched—polling averages show that these were three of the top four candidates, representing the top choice of more than 40% of poll respondents.Footnote 2 Moreover, whereas healthcare was only one of many salient issues, it has a demonstrated association with voting behavior (e.g., Nyhan et al. Reference Nyhan, McGhee, Sides, Masket and Greene2012), and polls from both before and after the survey administration show that healthcare was the top priority of Democratic respondents (Hrynowski Reference Hrynowski2020; Pew Research Center 2019). Thus, the relatively narrow focus of the treatments should still offer meaningful and realistic insight into the 2020 primary.

All survey subjects were shown the following prompt:

There are many individuals competing to be the 2020 Democratic Presidential nominee. Below are some of the issue positions held by three of the current frontrunners.

Subjects then were randomly assigned to view only one of the two charts shown in figure 1, which contain actual statements made by the candidates. In both, Biden was clearly against Medicare for All and Warren was clearly for it. The manipulation is whether Harris’s position was shown as clearly for or ambiguous.

Figure 1 Experimental Treatments

After exposure to the statements, subjects were asked to indicate which of the three candidates they preferred. After their preference was indicated, subjects then were told that President Trump opposes Medicare for All and were asked to indicate whether they would prefer Trump or Harris in the general election. Finally, subjects were asked to rate the favorability of all four individuals on a zero-to-100 scale.

RESULTS

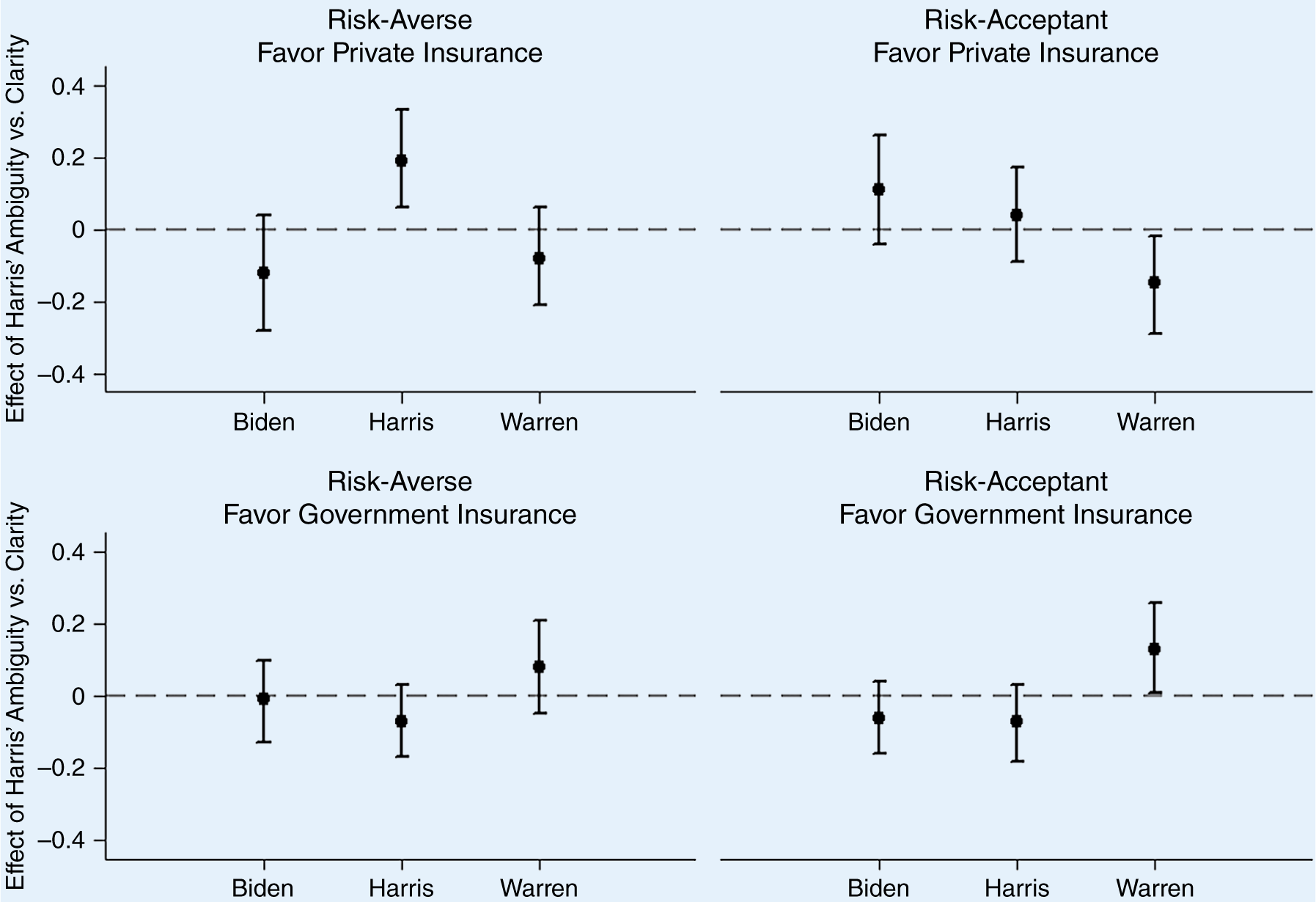

Although including all respondents does not change the main findings (see the online appendix), I present only the results of analyses of the 970 Democratic subjects in my sample because they are most relevant to a discussion of this primary election. I started by modeling primary vote preferences as a function of the treatment that the subject received and the subject’s preference for the status quo (i.e., private insurance). Preference for the status quo was measured using a single pretest item that asked subjects to place themselves on a seven-point scale that was rescaled to range from zero (i.e., medical expenses should be covered by a government-run insurance plan) to 1 (i.e., medical expenses should be covered by private insurance plans). I then used the pretest responses to the seven-question risk battery validated by Kam and Simas (Reference Kam and Simas2010)Footnote 3 to classify subjects as risk averse (i.e., those at or below the mean; N=477) or risk acceptant (i.e., those above the mean; N=483) and ran separate models for each group (Simas Reference Simas2020).Footnote 4 Full results of these multinomial models are available in the online appendix. Figure 2 plots the effects of the ambiguity treatment.

Figure 2 Effects of Harris’s Ambiguity on Democratic Primary Vote Choice

Notes: Estimates are derived from two multinomial logit models (see the online appendix). Points represent estimated effects and bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Opinions on health insurance are fixed at their 10th (0) and 90th (0.67) percentile values.

Figure 2 shows some gains associated with ambiguity. The risk-acceptant voters who favor private insurance were significantly less likely to support Warren when exposed to ambiguity. More directly, ambiguity significantly boosted Harris among the risk-averse voters who favored private insurance. This supports the claim that ambiguity can appeal to those who are reluctant to take risks if it still allows for a greater possibility of preserving the status quo or the most preferred outcome. In other words, Harris was “safer” for those who prefer private insurance plans when she was ambiguous because her vagueness allowed for a chance of keeping private plans; Harris’s clear statement removed that possibility.

Yet, even though ambiguity did appear to help Harris in some instances, these results should be considered in conjunction with the actual distribution of Democratic opinions on healthcare. More than one third of subjects selected the most liberal response option, whereas those with healthcare opinions conservative enough to be favorably moved by the ambiguity treatment comprised less than 18% of my Democratic sample. This is consistent with national polling from July 2019, which found that 81% of Democrats stated that the federal government has a responsibility to ensure that Americans have healthcare coverage (Dunn Reference Dunn2019). Moreover, among the risk-acceptant voters who favor government-run healthcare, ambiguity raised the likelihood of choosing Warren from 0.48 to 0.61. Therefore, my findings suggest that Harris’s ambiguity may have done more to boost the relative favorability of Warren than it did to help her own chances of winning the nomination.

Therefore, my findings suggest that Harris’s ambiguity may have done more to boost the relative favorability of Warren than it did to help her own chances of winning the nomination.

Models in the online appendix also fail to show ambiguity having any positive effect on Harris’s general-election prospects versus Trump because neither Democrats nor Republicans were moved by the treatments. This fits with my expectation that rhetorical strategies should matter more for distinguishing among candidates from the same party and counters claims that straddling the fence in a primary may help a candidate attract a broader set of general-election voters.

To further investigate how rhetorical differences impacted preferences for the candidates relative to one another, I examined subjects’ assessments of the candidates’ favorability. I constructed three variables that subtract either Biden’s, Warren’s, or Trump’s favorability rating from Harris’s favorability rating. The resulting variables ranged from -100 to +100, with positive values indicating a preference for Harris and negative values indicating a preference for the opponent. Using ordinary least squares, I modeled each in the same way that I modeled vote choice (see the online appendix). Table 1 presents the predicted values derived from these models.

Table 1 Predicted Relative Favorability Ratings of Harris

Notes: Cell entries are predicted values derived from OLS models in the online appendix. Opinions on health insurance are fixed at their 10th (0) and 90th (0.67) percentile values; *p<0.05.

Although these ratings were given after the explicit mention of Trump’s position, they were still similar to the expressed candidate preferences given before such information was presented. Among the risk-averse voters who favor private insurance, Harris fared better (although not significantly so) versus Biden and Warren when she was ambiguous rather than clear. The difference between clarity and ambiguity is still statistically significant for risk-acceptant voters who want government-run healthcare. Regardless of the opponent, ambiguity hurt Harris among these subjects. This again aligns with the theory that even risk-acceptant voters will dislike a gamble when compared to more certain prospects of their most preferred outcome. Somewhat counter to expectations, this held true even when comparing Harris to Trump. So, although ambiguity did not hurt Harris enough to push voters over to Trump, it still narrowed the favorability gap. This is important because the probability of turning out to vote decreases as the gap between impressions of candidates decreases (Holbrook et al. Reference Holbrook, Krosnick, Visser, Gardner and Cacioppo2001).

Of course, it is possible that the effects of ambiguity may be limited if those in the ambiguous condition were still aware of Harris’s more pro–Medicare for All statements. However, models in the online appendix show that my main findings hold even when the sample is restricted to those most likely to know Harris’s position—that is, the most politically knowledgeable.Footnote 5 Therefore, whereas ambiguity may help in some circumstances, it appears that, in this case, it may have done more harm than good.

DISCUSSION

Although broad appeals can offer electoral payoffs (e.g., Somer-Topcu Reference Somer-Topcu2015), my results illustrate important caveats suggested by previous research. I show that because the effects of ambiguity are contingent on both risk acceptance and preferences over the available alternatives, ambiguity can harm a candidate among those who most prefer a clear departure from the status quo without necessarily helping among those who do not. In the case presented here, this translated into ambiguity versus a clear position in favor of Medicare for All lowering Harris’s support among risk-acceptant voters who favor the government-run plan without offering fully offsetting gains among those who prefer to maintain some form of private insurance. This penalty was evident even when examining favorability relative to Trump, although analyses of general-election vote choice align more with studies that suggest that the effects of the party label may be too strong for candidates to escape, regardless of their rhetoric (Milita et al. Reference Milita, Simas, Ryan and Krupnikov2017).

This study has notable limits that have not yet been acknowledged. For example, Harris was flanked by clear alternatives on either side. Ambiguity may have more effect in situations in which alternatives also are somewhat ambiguous or in which one of the possible outcomes is not represented. Similarly, the both-sides type of issue stance used in the experimental treatment represents only one type of ambiguous statement (Milita, Ryan, and Simas Reference Milita, Ryan and Simas2014). It is possible that other types of ambiguity may have other effects. Finally, Harris’s race and gender may have conditioned the effect of ambiguity. As a person of color, she may have been subject to greater penalties for ambiguity (Piston et al. Reference Piston, Krupnikov, Milita and Ryan2018). However, as a woman, Harris may have been assumed to be more honest and less deceptive (Simas and Murdoch Reference Simas and Murdoch2020). Thus, it is unclear whether Harris was any more or less likely to be helped or harmed by ambiguity than a white or male candidate. Future research should probe further how various candidate characteristics interact.

However, all of these potential caveats only reinforce the argument that determining whether ambiguity is beneficial is complex and merits further exploration. Even with the possible confounds associated with using actual known candidates, my results provide evidence that generally aligns with what should be expected from a careful reading of the literature. Whether ambiguity helps or harms a candidate is conditional on many factors. When choosing a rhetorical strategy, candidates and their campaigns should be careful to consider both the nature of the target electorate and the other choices available to them.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Replication materials are available on Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NAH0FD.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1049096520001638.