Introduction

Agbadza and the Alorwoyie Project

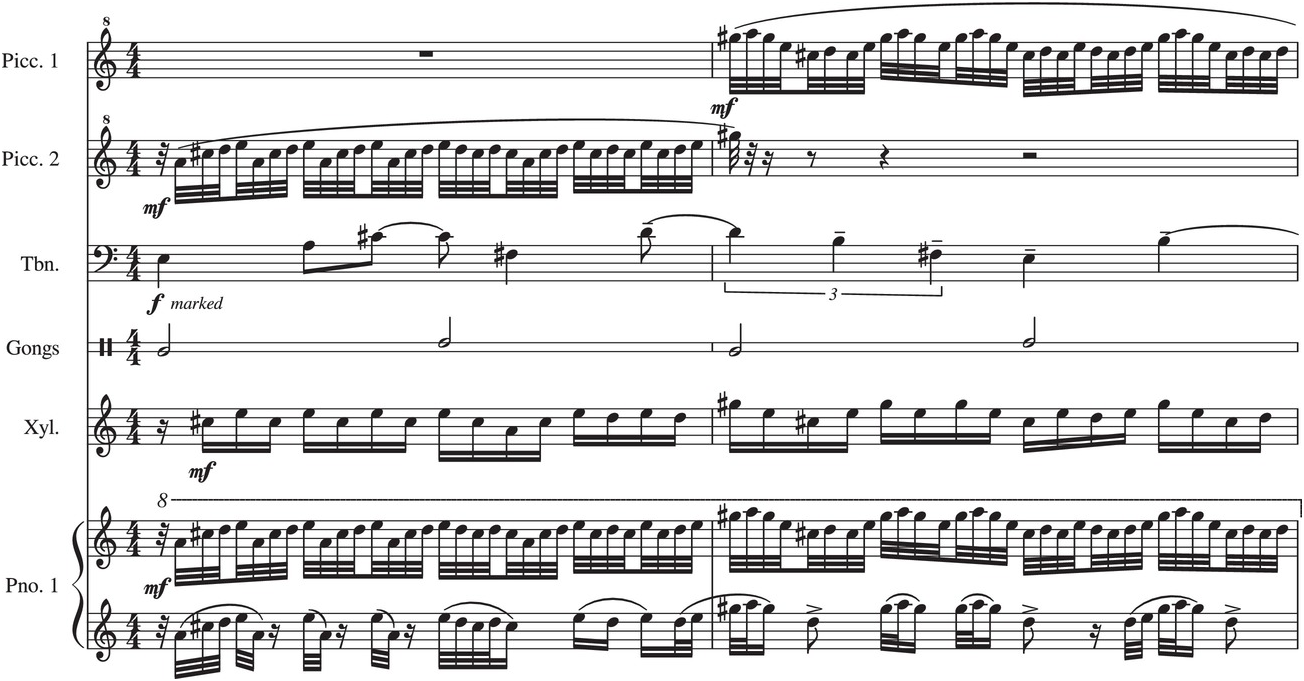

Agbadza is a genre of performance art that originated among the Ewe people (Ghana, Togo). The drumming features musical interactions between lead and response drums; in songs, poems are set to tunes that have a variety of call-and-response arrangements between several song leaders and a larger choral group. As discussed here, the rhythm of the vocal music contributes to the overall temporal vitality of an Agbadza performance.

The songs analyzed in this chapter may be heard on a recorded performance by Gideon Foli Alorwoyie1 and the Afrikania Cultural Troupe of Anlo-Afiadenyigba, Ghana, and are thoroughly documented on an online site (https://sites.tufts.edu/davidlocke/agbadza/).2 In what might be considered a long work in twenty-five sections, Alorwoyie paired songs with compositions for lead-response drums on the basis of the meaning of a song’s lyrics and the meaning of the drum language. Making the point about how it was performed during “the time of our grandparents,” Alorwoyie undertook this project to establish a historical baseline for contemporary musicians who would try new ways of playing Agbadza.3

Agbadza is generally regarded as the prototypical music and dance of the Ewe people. It began during a tumultuous era (1600–1900) of migration, conquest, and imperialism, including the trans-Atlantic African slave trade. Profound themes of life, death, and warrior ethos make it suitable for performance at funerals, memorial services, and rituals of chieftaincy. In Ewe communities, Agbadza can be heard at wake-keepings and memorial services. If one would posit the existence of an Ewe national dance, it likely would be Agbadza.

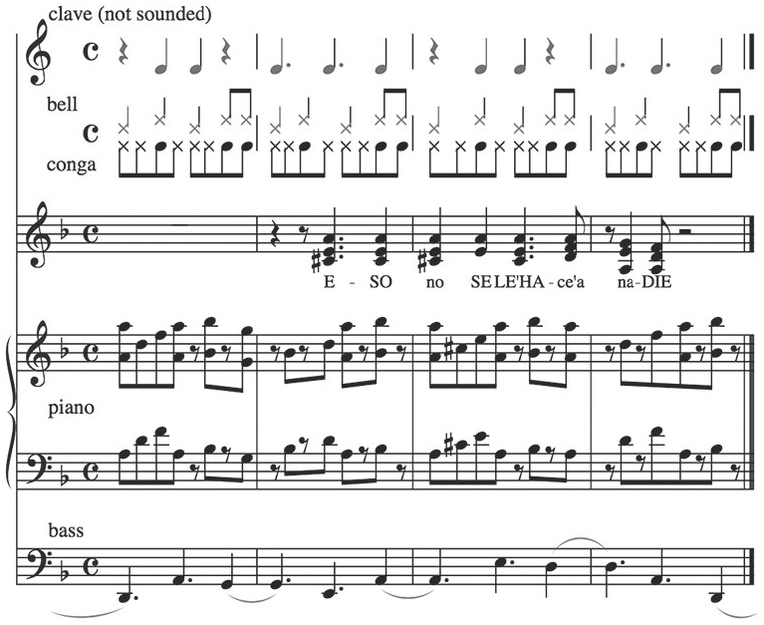

Agbadza’s instrumental music for drum ensemble features drum language compositions for the low-pitched lead sogo drum and medium-pitched response kidi drum that are set within a multi-part texture sounded by gankogui bell, axatse rattle, high-pitched kagan support drum, and handclap (asikpekpe).4

As may be heard on the audio files of Alorwoyie’s recording, at the beginning of each drum-dance item of Agbadza music, the song leader freely lines out the tune and text. After this brief introduction, the instrumental ensemble’s time parts start the phrases that they continue without variation for the duration of the item. The melo-rhythmic energy generated by this multi-part texture powers the singing and drumming.5 Guided by the bell phrase, the song leader raises the song in tempo, offering it to the group of singers who reply with gusto. When the song and the time parts are going nicely, the lead drummer plays the drum language phrases on the sogo using his two bare hands. The response drummer answers the leader’s call, using two wooden sticks to fashion the medium-pitched kidi drum’s recurring phrase. The lead drummer’s solo line complements the singers’ tune and weaves around the response drum’s phrase. In the recorded performance that is our source material, each song recurs with subtle musical variation before the lead drum signals the end of that item.

Author’s Preface

Stance

When cultural outsiders do inter-cultural musical analysis, it behooves authors to establish their positionality, especially in the case of Africa with its emotionally powerful histories of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, racial discrimination, and inequality. My stance toward Ewe performance traditions is that of an experienced student who is emboldened to teach and write to the extent of my knowledge and abilities. Compared to expert born-in-the-tradition insiders, I consider myself to be a relatively adept outsider. My authenticity depends on the veracity of information gathered in research, the quality of my ethnographic understanding, the value of my ideas, the clarity of my presentation, and the effectiveness of my pedagogy. Is my analytic apparatus relevant? Does it yield meaningful insight or explanation? Can other musicians make productive use of my publications?

In the text that follows, I position myself as the readers’ guide along a path we follow together toward an understanding of musical temporality in Agbadza songs. A discussion of specific songs will precede general conclusions about the full corpus of twenty-five songs in Alorwoyie’s Agbadza. This approach mirrors my own learning experience in which clarity emerged gradually from a fog of cognitive uncertainty. I feel that moving from the specific to the general guards the reader against adopting a premature sense of being able to comprehend Agbadza songs at a high level of abstraction and thus to assume control over them.

Analytic Toolkit

I write for all readers who would seek knowledge of music rhythm in Agbadza songs. I do not presume that readers have advanced knowledge of the theory and analysis of any of the world’s musics, whether Western Art Music or any of the world’s ethnic, folk, or traditional musics. Although I am enculturated into Western culture and have been schooled in Western institutions, I am largely self-taught in music theory and analysis.6 It may seem enigmatic, therefore, that my scholarly interest lies in transcription, analysis, and aesthetic criticism.

My analytic toolkit, so to speak, grew from direct engagement with Ewe performance arts. In trying to figure out “how the music works,” I have used a variety of notation systems and have explored diverse theoretical traditions. My writing aspires toward engaging the most sophisticated aspects of Agbadza’s music without either mystifying or condescending to the curious reader. I always try to make available audio files so that readers may also be listeners who do the hard work of bringing together the music itself with its representation in words and graphics.

Pitch

The musical instruments of Agbadza are tuned relative to each other and, as far as I know, no traditional instruments in Eweland are tuned to absolute pitches. The important issue in the tunes of songs is the intervals between pitch classes, not the precise pitches. Singers seem to use a range that is rather high in their comfort zone because this makes them audible in competition with the loud sound of the drum ensemble. The main range of pitch classes in an Agbadza song is an octave, with most songs extending as much as fifth above or below. Like most scholars, I believe staff notation to be adequate in representing the pitch material, even though the actual pitches and their intonation will always be at variance with a strict interpretation. I use simple capital letters to name pitches and assume readers will be able to follow my meaning when I write, “After opening the song with a dramatic relatively wide upward leap (C to G), Leader moves in steps and modest leaps until another large leap (D to A) and final downward step to G.”7

Because of the patterning of melodic motion, I will argue that pitch class sets in songs, “scales,” if you will, are essentially pentatonic in design even when there are more than five pitch classes in a tune. These pentatonic scales are either with or without semi-tones. Tunes sometimes feel organized around one tonal center, but because of their pentatonic structure many songs have more than one pitch class that functions as a place of tonal resolution. Due to their rather brief overall duration and their recurrent nature, the arrival at tonal conclusion on a song’s final tone always is short lived.

Rhythmic Mnemonics for Short-Long Time Values

The time values in Agbadza songs overwhelmingly are either short or long, represented here as eighth notes or quarter notes. Because I have found it immensely valuable to vocalize musical time values, I adopt the mnemonic “ti” to represent a short time value and the mnemonic “ta” to represent long time values.

Axiomatic Rhythm Concepts and Basic Terminology

The elapsing flow of musical time will be reckoned by timepoints, which in theory are equidurational but in practice may exhibit consistent non-isochronous microtiming.8 Elapsing musical time is felt to contain steady temporal marks that will be called beats; beats both divide the time span of the bell and add up to fill the measure. A beat will have one moment that is onbeat and other moments that are offbeat. A beat with three subdivisions is called ternary; a beat with two or four subdivisions is called binary or quaternary. In beats of binary morphology, the midpoint between successive beats is called the upbeat or the “and” of the count; this will be graphically represented with “&,” the ampersand. Ternary beats, which are foundational to Agbadza’s meter, have an onbeat timepoint (1.1), an afterbeat timepoint (1.2), and a third timepoint (1.3) that may either function as an unaccented pickup if it leads toward a subsequent onbeat tone or an accented offbeat if no note occurs on the subsequent onbeat. The first onbeat in a measure is designated as the downbeat; onbeat three is the midpoint in the measure; onbeats two and four are backbeats.

Accent

Accentuation in songs and drumming, that is, conferring especially strong feeling to particular musical moments, is an important subject in this chapter. Structural accentuation is built into Agbadza’s musical meter, the recurring themes sounded on the instruments in the drum ensemble, and the modal/melodic design of tunes. In tunes, for example, modal motion toward arrival on a tonicized pitch is one aspect of a composition’s structural accentuation. Notes that are onbeat or onbell will have different accentual valence than those that are offbeat or offbell. Within the polyphonic texture of the full music, notes in unison will have a quality of accentual force that is different from notes not reinforced by other parts. In the analytic system proffered here, each component of the music projects accentual power onto the others. As is true in many of the world’s musics, Ewe composers often position a musical note on a structurally unaccented position, which paradoxically gives it special potency for intense musical feeling. In contrast to the features of accentuation that are embedded into the design of an item of Agbadza music, during performance musicians will make spontaneous decisions about timing, pitch, and timbre. The various publications of Alorwoyie and Locke provide ample evidence for study of expressive accentuation, so to speak, but this subject is not addressed here.

Graphic Representation

In prior work I have used staff notation to graphically represent Agbadza’s music and will refer readers to these musical examples, which are readily available online. Inevitably, staff notation is regarded by some readers as a sign of a non-African, Western epistemic regime, a semiotic assumption I wish to counteract. Here, I use the Time Unit Box System (TUBS), which is an excellent way to depict temporal relationships. Like staff notation, time moves on the page from left to right, with one graph box equating to one musical timepoint. Readers who would like to see musical examples in staff notation should follow the hyperlink references.

Audio/Visual Documentation

The music discussed in this chapter is available in two ways: a book with audio CD and an online site (https://sites.tufts.edu/davidlocke/agbadza).9 The online site contains Ewe texts for songs and drumming, various translations into English, lead sheets for songs and drum compositions, complete note-for-note transcriptions of the audio files, interviews with Alorwoyie, and analytic criticism of each of the twenty-five items of Agbadza in Alorwoyie’s project.

The Musical Rhythm of Agbadza Songs

Our journey into the rhythm of Agbadza songs begins with the fundamentals of musical time in Ewe dance-drumming. The path begins with the bell part.10 In genres of Ewe dance-drumming music, the bell part sounds over and over as a recurrent temporal theme that gives to musical time a distinctive pattern or shape.

Learning the Bell

Seven hits with a straight stick on the iron instrument take a player through one occurrence of the bell’s theme. The time values are of two types: short notes (“ti”) and longer tones (“ta”) that are twice the duration of the quicker tones. (The custom in scholarship about Ewe music is to notate these sound events as eighth notes and as quarter notes.) Ewe experts teach the bell part as the sum of two figures: (ta ti ta) + (ta ta ti ta). Alorwoyie teaches that when the music begins, the bell player should strike first on the lower-pitched of the gankogui’s two bells and then play all other notes on the higher-pitched bell. The first appearance of the bell theme thus suggests the following pattern of time values – (ta ta ti ta ta ta ti ta) + (ta … ).11 To summarize: two grouping patterns of the time values are recognized by culture-bearers as foundational: (1) ta ti ta ta ta ti ta, and (2) ta ta ti ta ta ta ti.

Taking the duration of the short bell tone as a unit for measuring musical time, we observe twelve units within one full occurrence of the phrase. The two fundamental ways of hearing or grouping the bell pattern may thus be rendered numerically as (A) 12 = (2+1+2) + (2 + 2 + 1 + 2), and (B) 12 = 2 + 2 + 1 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 1. Readers familiar with the scholarly and popular literature on African music likely will recognize the second formula, but I emphasize the ethnographic significance of the first formula and suggest its importance for those who would desire to enter what might be termed “an Ewe way of hearing.” As a teacher of this music myself, I echo my Ewe teachers who urge students to hear rhythmic shapes in actual musical phenomena rather than counting time according to an abstract mathematical schema (meter, time signatures). Paradoxically, meter is of vital importance.

The Bell in Four: Ternary-Quadruple Time

Agbadza moves with steady tempo that may be felt according to recurring temporal units (beats). Dancers typically step (transfer weight from foot to foot) in unison with these beats.12 Four beats occur over the time span of one bell phrase. The two-part polyrhythmic duet between the asymmetrically shaped bell part and the steady flow of the equidurational beats is absolutely at the bedrock foundation of Agbadza’s musical temporality. Overwhelming evidence suggests that the bell phrase typically is felt “in four.” In other words, if and when players or listeners want to reference metric units, they will attend to what I will refer to as “four-feel beats” (dotted quarter notes). The twelve units within one span of the bell phrase thus are structured into four ternary beats: 12 = 4 × 3.

How shall bell part, beats, and faster pulses be set within a recurring musical cycle or metric framework? Study of the bell phrase shows that the note played on the low-pitched bell is its main moment of musical resolution and therefore a prominent moment of accentuation in the permanent structure of the music. Furthermore, this is the temporal location in the ever-cycling pattern toward which other parts move for cadence. Even when what the late Ewe scholar Willie Anku termed the “regulative time point” is not accentuated by other parts, the RTP nevertheless serves as a temporal reference point.13 Despite positing that ONE comes at the end of the phrase, I join other scholars of Ewe music who place it at the beginning of measures and assign numbers from there (see Table 13.1). For the sake of simplicity, I will simply use capitalization to denote these crucial timepoints in the music’s ongoing flow. To summarize our presentation of the bell part: seven short and long tones in two grouping patterns occur over twelve quick pulses that are shaped into four ternary beats.

Table 13.1 Fundamentals: 12-pulse, 4-beat, bell phrase

| 12-Pulse | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 01 | 02 |

| 4-Beat | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Bell | Ta | ta | Ti | ta | ta | ta | ti | ta | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1 |

Meter as a Matrix

Elsewhere, I have suggested that it is productive to think of Ewe meter as a nexus of temporal fields that are interconnected in a matrix-like relationship.14 In genres disciplined by ternary beats, a multidimensional quality arises from the presence of time values in a three-with-two temporal ratio. In staff notation, this can be represented with “dotted notes” and their “undotted” counterparts and signaled through time signature – ![]() :

: ![]() . This ratio happens between time values of different durations in a multilevel structure that reminds me of a three-dimensional chess board. When the span of the bell phrase establishes a four-beat quadruple measure, the music has the simultaneous presence of metric beats in three time signatures –

. This ratio happens between time values of different durations in a multilevel structure that reminds me of a three-dimensional chess board. When the span of the bell phrase establishes a four-beat quadruple measure, the music has the simultaneous presence of metric beats in three time signatures – ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() – as well as their double-time and cut-time derivatives. Finally, accentuation may be consistently placed on offbeat moments within a metric beat, which multiplies the relationships among metric fields.15

– as well as their double-time and cut-time derivatives. Finally, accentuation may be consistently placed on offbeat moments within a metric beat, which multiplies the relationships among metric fields.15

In traditional music genres like Agbadza, the flow of metric units is normally experienced as a background part of mental and physical consciousness rather than actively counted as a timing reference. Many African-born teachers instruct students to refrain from tapping their feet as a method of keeping time, for example. To emphasize the phenomenal presence of metric units, I use the word feel in my writing as in “four-feel beats” or “six-feel beats.” I theorize the constant presence of the “metric matrix” as an implicit and latent resource to inspire creativity, guide timing, shape accentuation, and enhance expressiveness.

The Drum Ensemble Context

The bell part structures musical time for dancers, singers, and drummers. The instrumental ensemble consists of one bell, many hand clappers, many rattles, one high-pitched support drum, one medium-pitched response drum, and one lead drum. Each part in the ensemble establishes its own musical personality and also makes its own distinctive contribution to what Meki Nzewi suggests we call the “melo-rhythm” of Agbadza’s “ensemble thematic cycle (ETC).”16

Format of Songs

Agbadza songs are sung by a chorus of singers in two parts – Leader and Group.17 The leader part actually may be performed by as many as three or four people, although one person will be regarded formally as “song leader.” The group part, on the other hand, is sung by many voices. Contrast in texture and energy between the few voices in Leader and the many voices of Group is a prominent quality in these songs. In the Alorwoyie’s Agbadza project, the song leader began each item with a short, temporally loose rendition of the song without instruments. Once the song was “lined out,” the ensemble entered and the full version of the song started.

Selected Agbadza Songs

Let us now consider several songs. General rhythmic characteristics will emerge through discussion of these specific tunes and texts.18

In this discussion of musical rhythm in the twenty-five songs in the Alorwoyie Agbadza project, “Kaleworda” will represent a typical or average song. Its comparatively uncomplicated musical features are a good place to start.

Over the span of four bell cycles, song leader and singing group each sing the same two-sentence lyric about the lonely death of a strong warrior on a distant battlefield (see #7, Song Lyrics).19 The tune’s pitches array within an octave except for the upper A in the Leader’s opening motive (see #7, Lead Sheet). Leader works higher in the pitch set, while Group lowers the melody to its final note on the lower G. After opening the song with a dramatic, relatively wide upward leap (C to G), Leader moves in steps and modest leaps until another large downward leap (D to A) and final downward step to G. The group’s reply centers on C until it too descends to G with cadential leap-step motion (D–A–G). With the exception of B♭in m. 4, the tune uses five pitch classes.20 To me, the song’s pitches move toward modal and temporal conclusion on the final G, but C also feels like another, complementary “tonicized pitch,” so to speak; this would mean that the song’s tonality is a pentatonic scale without half-steps in the modes G–A–C–D–F (2–3–5–6–1) and/or C–D–F–G–A (5–6–1–2–3). Both parts in the call-and-response are of equal duration – two “measures of bell,” so to speak – and set the text with the same time values as shown in Table 13.2.

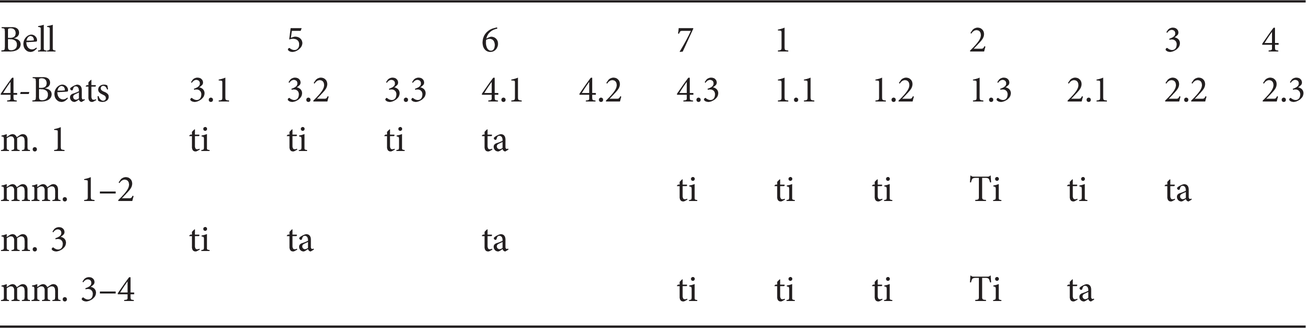

Table 13.2 “Kaleworda” time values in melody

| Bell | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| 4-Beats | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| m. 1 | ti | ti | ti | ta | ||||||||

| mm. 1–2 | ti | ti | ti | Ti | ti | ta | ||||||

| m. 3 | ti | ta | ta | |||||||||

| mm. 3–4 | ti | ti | ti | Ti | ta |

The rhythmic design of its time values contributes to the musical personality of the melody. The words to the song are rendered in four nearly identical rhythmic figures, each spanning two four-feel beats (see Table 13.2). The idea stated in m. 1, that is, motion in eighth-note values between successive onbeats, establishes a pattern that is slightly modified in the three subsequent rhythmic patterns.

Subtle differences among these four rhythmic figures enable each variant to project its own quality to the flow of time within the span of one bell phrase and each has a particular relationship to notes in the bell phrase (Table 13.3).

Table 13.3 “Kaleworda” temporal effect of melodic rhythmic patterns

| m. 1 |

|

| mm. 1–2 | |

| m. 3 | |

| mm. 3–4 |

Discussion of “Kaleworda” has introduced musical features common in most all Agbadza songs. Call-and-response between the leader and group parts is a foundational aspect of a song’s temporal design. The timing of the transfer in vocal action between Leader and Group parts, that is, the rhythm of call-and-response, and the consequent change in musical texture that results is an important component of Agbadza’s overall rhythm. Their exchange establishes a before-after temporal structure that provides an opportunity for antecedent-consequent musical logic, which may include aesthetic forces of tension-resolution. The timing of shifts in tonal centers within a pentatonic scale exerts yet another rather large-scale temporal effect. At a more fine-grained dimension, the rhythmic patterns of time values in the melody make polyrhythm with the bell phrase. As if it were another drum in the ensemble, the melodic rhythm may be heard to project musical forces toward other instruments, imparting nuances of accentuation on onbeat and offbeat timepoints to a listener’s interpretive experience of the polyphony.21 Finally, the song’s musical form, which is shaped by call-and-response design as well as by melodic factors of tunefulness, so to speak, has impact on a song’s rhythm through the comparative duration of its several sections.

Let us review the specific temporal features of this song that are characteristic of most songs among the twenty-five in the Alorwoyie collection. First, Leader was higher in the song’s range and had more tonal movement; Group quieted the rhythmic activity of the tune as it lowered the song’s pitches toward the finalis.22 Second, in a straightforward A1A2 form, Leader and Group both set the same text to identical time values; each part made a coherent melodic statement, but the two parts preceded and followed each other according to an Ewe musical logic of melodic gesture, pentatonic tonality, and rhythm governed by bell phrase and meter. Third, time values had a memorable theme – in this case, eighth-note motion through successive four-feel onbeats – that helped unify the tune.

Although I have proposed this song as being prototypical, every Agbadza song is unique. Overall, the genre has characteristic style, but each venerable song was intentionally crafted to convey particular meaning.

Like “Kaleworda,” this song spans four bell cycles and has two exchanges between Leader and Group (see #2, Lead Sheet). But the rhythmic design of “Miwua 'Gbo Mayi” is much more asymmetric and the relationship between Leader and Group much more intertwined.

The melody has three phrases with a rounded ABA form in the span of four bell cycles (see Table 13.5). Although the metric structure groups the ternary beats into sets of four (quadruple meter), the pattern of call-and-response confers an asymmetric design: 16 = (3+3) + 5 + 5 (see Table 13.4).

Table 13.4 “Miwua 'Gbo Mayi” asymmetry in duration of melodic phrases

| Phrase 1 | L: 3-4-1 + G: 2-3-4 | six beats (3+3) |

| Phrase 2 | L: 1-2-3-4-1 | five beats |

| Phrase 3 | G: 2-3-4-1-2 | five beats |

Table 13.5 “Miwua 'Gbo Mayi” four-feel of call-and-response

| Measure | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| Beats | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Phrases | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||||||||

| Form | A | B | A | |||||||||||||

| c-r | L | G | L | G |

Leader and Group share in the song’s dramatic opening lyric, “Brave ones, open the gate. I will go” (see #2, Song Lyrics). Begun by Leader on four-feel beat three (m. 1), Phrase 1 requires a hand-off to Group on four-feel beat two (m. 2). Leader’s relatively long Phrase 2 fits neatly within one complete bell cycle: 1–2–3–4–1. As it did in Phrase 1, in Phrase 3 Group takes over the flow of four-feel beats from Leader on beat two (m. 4) with another five-beat gesture that extends through the next ONE: 2–3–4–1–2.

The tune adds more intricate melodic rhythm to this motion of metric units. The Leader begins the first phrase with upward and downward pendular leaps of a minor third interval (B–D–B) in a rhythm that aligns with the bell’s cadential motion over tones 5–6–7–1 (mm. 1–2).23 Countering the structural tendency of the music to reach cadence on ONE, the Group quickly continues the melody’s rhythmic flow with an upward half-step on timepoint 2.2. Together, the melodic rhythm of the two sub-phrases in Phrase 1 articulates an important metric rhythm in Agbadza’s music: the oscillation within the span of one bell cycle between a half-measures “in three” and “in two” (see Table 13.6).24

Table 13.6 “Miwua 'Gbo Mayi” three-then-two pattern in melodic rhythm

| Bell | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||||

| 4-Feel beats | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||

| 6-Feel beats | 4 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||||||

| 2:3 Accentuation | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||

| Song text | Mi- | wua | 'gbo | ma- | yi | Ka- | lea- | woe |

Each part is restricted to two pitches, but the Group part stands out for its long sustained note on C that sets the word with a key semantic image: brave Ewe warriors (see #2 Song Lyrics). Tonally and rhythmically, the melody creates a feeling of anticipation for phrase 2 (m. 3). Into this musical space, the Leader jumps boldly with a dramatic downward gesture that begins in polyrhythmic contrast to bell before aligning with its cadential tones to arrive at G on timepoint 1.1 (m. 4). In the lyric, this powerful melody establishes that the song is about struggle between the Ewes and their prototypical enemies, the Fon people of Dahomey. Although rhythmic motion of Phrase 2 achieves a sense of closure by aligning with bell’s cadence to ONE (m. 4), the Group again enters rather quickly (m. 4), this time with its own long phrase that arches upward to D before the final plunge to F♯ (m. 5), which to my ear leaves the whole song in an unresolved tonal condition. In a clever feature of the song’s text setting, the rhythm of the final word, “Dahomey,” imitates the two prior positions of “brave ones” (m. 2, m. 4). I especially enjoy the design of the rhythmic figures in this phrase, which suggest a palindrome: 3–2–1–2–3 (mm. 4–5) (see Table 13.7).

Table 13.7 “Miwua 'Gbo Mayi” palindrome

| Syllable count, number of onsets | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Text | Ka-lea-woe | mi-wua | 'gbo | ma-yi | Da-hu-me |

Some Agbadza songs feel especially drum-like (see Items #13 and #21): the sectional form moves quickly between Leader and Group, the melody reiterates only a few pitches, and the rhythms are repetitive and percussive. Compared to the tuneful setting of poetic text in songs like “Kaleworda,” these songs seem more like chants to “rally the troops,” so to speak. Because the singing functions like drumming, this song provides us with an opportunity to go deeper into the music of the drum ensemble.

The song lyric expresses quintessential warrior bravado: “The battlefield is for men. If I die, bury me there” (see #21, Song Lyrics). To enhance the feeling of urgency, Alorwoyie selected an extraordinarily intense composition for lead and response drums that sets the scene with the insistent statement, “On the battlefield,” and/or “The brave place” (see #21, Drum Language). Rhythmic intensity derives from the unusually short time span of the drum parts – only two four-feel beats. Two bounce tones from the response drum align precisely with a similar figure in the high-pitch support drum, thus joining the power of each instrument in a new synthesis (see #21, Full Score). One rhythmic consequence of the fusion of these two drumming parts is accentuation of the fast-moving eight-feel beats, which suggests a “double-time” feeling of tempo. (Compare to the quality of “cut-time” accentuation in “Ahor De Lia Gba 'Dzigo,” below.)

The song leader insistently intones the same lyric, “Battlefield-men’s place,” to a short descending motive (D–C–A) whose rhythm carries the feeling of metric closure – three–four–one motion of the four-feel beats – as well as the bell phrase’s cadence to ONE over strokes 5–6–7–1 (m. 1, m. 3, m. 5). The singing group responds with a sequence of two melodic phrases that end first on D (m. 3) and last on G (m. 5), which conveys a fleeting feeling of tonal and rhythmic stasis before the song’s next iteration.

The time values in Group’s part have an ingenious impact on the overall polyrhythmic texture. I enjoy hearing this rhythm as two successive occurrences of a four-note motive – ti ta ta ta – that is launched first from the pickup to four-feel beat two (timepoint 1.3) and then again from the onbeat of four-feel beat four (timepoint 4.1). The note with short time value (“ti”) functions like a temporal switch that toggles the melodic rhythm back and forth between the upbeats and the onbeats of the six-feel beats (see Table 13.8); the handclapping part gives phenomenal presence to this counter-metric field. The same toggling procedure happens within every cycle of the bell phrase: the short note on timepoint 2.2 shifts the bell’s long tones into unison with the flow of beats in the upbeat six-feel until the short note on timepoint 4.3 returns the long bell tones into unison with the flow of beats in the onbeat six feel. In this song, a similar procedure creates two identical rhythmic patterns that make very effective polyrhythmic interaction with bell.

Table 13.8 “Dzogbe Nye Nutsu Tor” toggling onbeat and upbeat six-feel beats

| 4-Feel | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| 6-Feel | 1 | & | 2 | & | 3 | & | 4 | & | 5 | & | 6 | & | 1 | & | 2 | & | 3 | & |

| Song | ti | ta | ta | ta | ti | ta | ta | ta | ||||||||||

| Bell | ta | ta | ti | ta | ta | ta | ti | ta | ta | ti | ta |

Songs discussed thus far have illustrated rhythmic dynamism in Agbadza songs. Whether due to factors such as the duration of composed themes, formal design, metric accentuation, or the pattern of its time values, the melodic rhythm of these songs adds to the ever-changing quality of Agbadza’s overall musical temporality. The next two songs illustrate a different capacity: the steady and relatively unambiguous accentuation of one kind of metric field, that is, the flow of four-feel or six-feel metric beats. Although the musical rhythm of Agbadza will always be malleable to different interpretations, in these songs we hear and feel strong alignment between a song’s accentuation and the foundational time feels of Agbadza.

In many ways, “Ahor De Lia Gba 'Dzigo” is a classic Ewe song. The song lyric heralds a sneak attack on Adzigo, a legendary center for Ewe warriors, a message enhanced by the drum language’s command, “Put on your war belt” (see #17, Song Lyrics and Interview). Although more fully developed than “Kaleworda,” the design of the call-and-response, the melody’s shape, and the song’s form are typical for a dance-drumming song (see #17, Lead Sheet): an opening section (A1A1) in which Leader and Group twice exchange relatively long phrases (mm. 1–6); a middle section (B1B2) with faster call-and-response timing (mm. 6–10); and a reprise of Group’s phrase from the opening section (A2) (mm. 11–12).

Time values in Leader’s melody make a memorable rhythmic topography, so to speak (see Table 13.9, bold shading shows accentuation).25

Table 13.9 “Ahor De Lia” melodic rhythm of Leader phrase

| Measures 1–2 | ||||||||||||

| Beats | 2.3 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Song | ti | ti | ta | ta | ti | ti | ta | ti | ta | |||

| Measures 2–3 | ||||||||||||

| Beats | 2.3 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Song | ti | ta | ta | ti | ti | ta | ta | |||||

The prominent notes on every onbeat enable a listener to feel the melodic rhythm as conferring accent to the four-feel beats. With long notes initiated from timepoints 3.1 and 1.1 (mm. 3–4), Group’s reply reinforces this hard-driving onbeat rhythmic quality.26 Because it continues with the same text and time values in its B and A2 section, the entire song has an “onbeat four” quality of rhythmic accentuation. This is not the full story, however, as will be discussed below after a brief detour into the theory of Ewe meter.

In Agbadza’s musical meter, four-feel beats with ternary subdivision (dotted quarter notes) always are balanced by six-feel beats with binary subdivision (quarter notes). The co-existence of two types of metric units imparts to the music a permanently ongoing three-with-two temporal ratio (3:2 over a half-measure; 6:4 within one bell cycle) that makes patterns in Agbadza’s music amenable to different rhythmic interpretations. The timing of the implicit four-feel beats will be so familiar to persons competent in Ewe music that the explicit iteration of the six-feel beats by the hand-clapping part in the Alorwoyie recordings likely makes for a pleasing counterpart. Just as some songs align to the four-feel beats, a song may also “be in six,” if I may put it that way.

“Dzogbe Milador” exhibits steady accentuation of the onbeat six-feel beats (see #12, Lead Sheet). Because the time values in the A section (mm. 1–5) tend toward uniformity in eighth notes, they do not suggest a particular accentual pattern in and of themselves. However, the syllabic division of words in the text and the choice of pitches in the tune bring out the “onbeat six-feel,” suggested by the bold shading in Table 13.10.

Table 13.10 “Dzogbe Milador” A section, melodic rhythm accentuation of onbeat six

| Measures 1–2; Leader | ||||||||||||

| Beats | 4 | & | 5 | & | 6 | & | 1 | & | 2 | & | 3 | & |

| Song | Dzo- | gbe | mi- | la- | dor | Be | dzo- | gbe | mi- | la- | dor | |

| Measures 2–3; Group | ||||||||||||

| Beats | 4 | & | 5 | & | 6 | & | 1 | & | 2 | & | 3 | & |

| Song | Fon | ma- | de | ma- | de | Be | dzo- | gbe | mi- | la- | dor | |

While this quality of rhythmic accentuation is unequivocally present in the Leader’s part, in the Group part (m. 2), the consecutive eighth notes on pitch A present a more rhythmically malleable situation that could be felt in sets of three, i.e., organized within ternary beats three and four.

In the B section (mm. 5–7), Leader and Group combine their incomplete melodic fragments to set one line of text to a full tuneful idea; the melodic rhythm continues to accentuate the onbeat six-feel beats (see Table 13.11, bold shading shows accentuation).

Table 13.11 “Dzogbe Milador” B section, melodic rhythm accentuation of onbeat-six in B

| Measures 5–6 | ||||||||||||

| Beats | 4 | & | 5 | & | 6 | & | 1 | & | 2 | & | 3- | & |

| Song | L: Tu- | le a- | si | da- | da | glo | G: Me- | yi- | na | |||

| Measures 6–7 | ||||||||||||

| Beats | 4 | & | 5 | & | 6 | & | 1 | & | 2 | & | 3 | & |

| Song | L: He- | le a- | si | da- | da | glo | G: Me- | yi- | na | Be | ||

For the first time in our discussion, this song has a C section with important new information in the lyrics. In the A section, Leader and Group both conveyed the message “As warriors, we are prepared to die on the battlefield.” In the B section, the song belittled the effectiveness of the enemy’s weapons, “Your guns cannot shoot. Your knives cannot cut.” The confidence expressed in these lines is tempered in the C section: “Men will die in battle, while women await their own deaths back at home.” As if to give the turn in the song’s poetry a new musical setting, the melody’s pattern of steady accentuation changes dramatically from being “in six” to being “in four” (mm. 7–9). Melodic motion on B♭ and D confers the feeling of grouping within ternary beats onto the long set of nine eighth notes that lead to the onbeat dotted quarter note on G in m. 8, that is, the four-feel groove (see Table 13.12, bold shading shows accentuation).

Table 13.12 “Dzogbe Milador” C section, melodic accentuation “in four”

| Beats | 2.3 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 |

| Song | Be | nu- | tsu- | wo | ku | me- | Le | dzi- | dzi | 'fe | o |

Then at the midpoint of m. 8 (timepoint 3.1) comes a striking departure from the prior time values of eighths and quarters: a dotted figure followed by highly distinctive duplet motion through beat one of the next bell cycle (m. 9).27 This is a clear instance of melody dramatizing the meaning of song text. In the closing return of section A (mm. 9–10), Group brings back its opening phrase, thereby ending the song with a return to its accentuation of the six-feel beats.

Multistability is the normal condition of musical rhythm in Agbadza. The primacy of the four-feel beats notwithstanding, the design of tunes usually enables more than one way to interpret the song’s rhythmic accentuation and melodic grouping. I suggest that this very quality of temporal dynamism is a reason why traditional genres of music like Agbadza have been popular among Ewe people for centuries. The songs and drumming never will become stale as long as people listen creatively. We return to “Ahor De Lia Gba 'Dzigo” to illustrate.

Above, “Ahor De Lia Gba 'Dzigo” served to exemplify steady accentuation of the four-feel onbeats. Returning again to this song, we can observe how its melodic rhythm also conforms to the resultant rhythm of time values in 3:2 between quarter notes and dotted quarter notes – ta ti ti ta, ta ti ti ta, etc.28 In this song, the four-note 3:2 pattern is phrased ti ti ta TA, that is, from offbeat pickup, through onbeat two, toward onbeat one, with the final “ta” aligning to the moment when the two timing streams come together in unison (bold shading and capitalization shows accentuation). From the temporal perspective of the “three side” of 3:2, the melodic rhythm in this song may be said to consistently align with the “ands” of six-feel beats, that is, the flow of upbeat six-feel beats (see Table 13.13, bold shading shows accentuation).

Table 13.13 “Ahor De Lia Gba 'Dzigo” accentuation of upbeat six

| Measures 1–2 | ||||||||||||

| Onbeat four | 2.3 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Upbeat six | 3& | 4& | 5& | 6& | 1& | 2& | ||||||

| Song | ti | ti | ta | ta | ti | ti | ta | ti | ta | |||

| Measures 2–3 | ||||||||||||

| Onbeat four | 2.3 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| Upbeat six | 3& | 4& | 5& | 6& | 1& | 2& | ||||||

| Song | ti | ta | ta | ti | ti | ta | ta | |||||

Ewe metric theory reveals another consequence of accentuation on the “upbeat six”: moments of unison between upbeat six-feel beats and the onbeat four-feel beats occur on four-feel beats two and four, not one and three. In other words, notes timed to flow of the upbeat six-feel beats tend to accentuate the backbeats, a well-established hallmark of music in the African Diaspora.29

Summary

The foregoing discussion has familiarized us with the overall nature of musical temporality in Agbadza songs and provided opportunity to articulate many of its more sophisticated features of rhythm. Let us summarize.

The bell part establishes the conditions of musical time:

▪ ever recycling temporal condition

▪ duration of time span or measure

▪ distinct pattern of sounded time values and unsounded timepoints using two time values – long and short

▪ two grouping shapes of full theme: (A) ta ti ta ta ta ti ta, (B) ta ta ti ta ta ta ti

▪ segmentation into fragments: (A) ta ti ta + ta ta ti ta

▪ cadential motion over onsets 5–6–7–1 toward fleeting moment of stasis (ONE)

▪ strokes 7 and 1 are onbeat in the four-feel

▪ toggling between onbeat six-feel beats (onsets 1, 2, 3) and upbeat six-feel beats (onsets 4, 5, 6, 7)

Meter establishes duration, subdivisions, and structural accents:

▪ ternary-quadruple time or “the four-feel beats” (four groups of three) is foundational

▪ binary-sextuple time or “the six-feel beats” (six groups of two) is a permanent complement

▪ three-with-two (3:2) is omnipresent

▪ the accentual force of four-feel beats ranges from most stabile to most motile as follows: 1–3–4–2, that is, downbeat, midpoint, backbeat, backbeat

▪ four-feel beats 1 and 4 are onbell; four-feel beats 2 and 3 are offbell

▪ six-feel beats 1–3 are onbell, six-feel beats 4–6 are offbeat

▪ three timepoints within one ternary beat: the onbeat timepoint (1.1), the afterbeat timepoint (1.2), and a third timepoint (1.3) that may function as either an unaccented pickup if it leads to a subsequent onbeat tone or an accented offbeat if no onset occurs on the subsequent onbeat

▪ two timepoints within one binary beat: onbeat and upbeat

▪ matrix conception: steady flow of onbeats, offbeats, and upbeats in 3:2 ratio at different durational values

Accentuation, heightened feeling of a particular musical moment, is made in several ways:

▪ structural: resulting from permanent nature of bell, meter, recurring themes of parts in drum ensemble, and scale/mode

▪ compositional: resulting from design of song and lead-response drum composition

▪ positional accent: first or last note in a group

▪ pentatonic scales and modes: multiple potential tonal centers

▪ song finali often is tonal center but not always

▪ recurrent cyclic nature of music time continuously refreshes accentual patterns of motility and stasis

Song design has impact on musical rhythm in many ways:

▪ overall duration: from relatively short to relatively long

▪ organization of motion through metric fields and bell phrase

▪ moments of beginning and ending on bell and within meter

▪ timing of transfer between Leader and Group; rhythm of call-and-response; each part may achieve melodic closure or, alternatively, the two parts may combine to make one phrase

▪ duration of Leader and Group parts: long Leader–short Group; short Leader–long Group; equal duration of Leader-Group

▪ rhythm of tonal motion: motion toward and arrival at tonal centers; timing of moments of tonal stasis on bell and in meter

▪ temporal features of musical form (design of melody considered together with design of call-and-response): A sections – tuneful, B-sections – percussive, C sections – tuneful but different and distinctive

▪ overall before-after temporal/tonal patterns: from temporally busy and high-pitched at a song’s beginning to temporally quiet and low-pitch at its end

Melodic rhythm, that is, the design of time values in a melody, projects temporal force just as do the musical instruments in the drum ensemble:

▪ Duet with bell and each instrument

▪ Composite rhythm with other parts

▪ Metric placement of onsets

▪ Surface pattern: variegated time values make a definite rhythmic shape; unvaried time values have neutral temporal shape and are susceptible to being shaped by the force of other parts (malleability)

▪ 3:2 as a pattern of time values (ta ti ti ta); melodic rhythm often phrased ti ti ta ta.

▪ consistent accentuation of a metric field, and/or a metric rhythm such as three–then–two, or three–four–ONE

▪ musical dramatization of the meaning of song lyrics by a shift in accentual pattern or other means

▪ non-isochronous timing of two-note, short-long figures when short first note is onbeat

▪ temporal motion toward accentuation at the end of phrases

▪ clever design: palindrome; short riff repeated with difference on bell or meter; alignment with instruments in ensemble

▪ internal references: motivic variation, melodic sequence, recurring rhythmic figures

Conclusion

The onbeat four-feel groove in duet with the seven-note bell theme provides the ultimate temporal logic of Agbadza, but perhaps because this foundation is so well established, a plethora of countervailing forces may be put in play without threatening the music’s groove. Agbadza’s melodic rhythm might be characterized as iridescent: it resists a one-way interpretation and may be perceived to change depending on its setting in musical context. In Agbadza, everything musical happens within an interactive network of mutual influences: instrumental parts in a multi-part ensemble, meter as a dynamic matrix, and songs with multistable temporal design. Songs are designed to fit with other parts in interesting and musically satisfying ways. Like the other components of Agbadza music, a song acquires its full nature only in relationship to things outside itself.

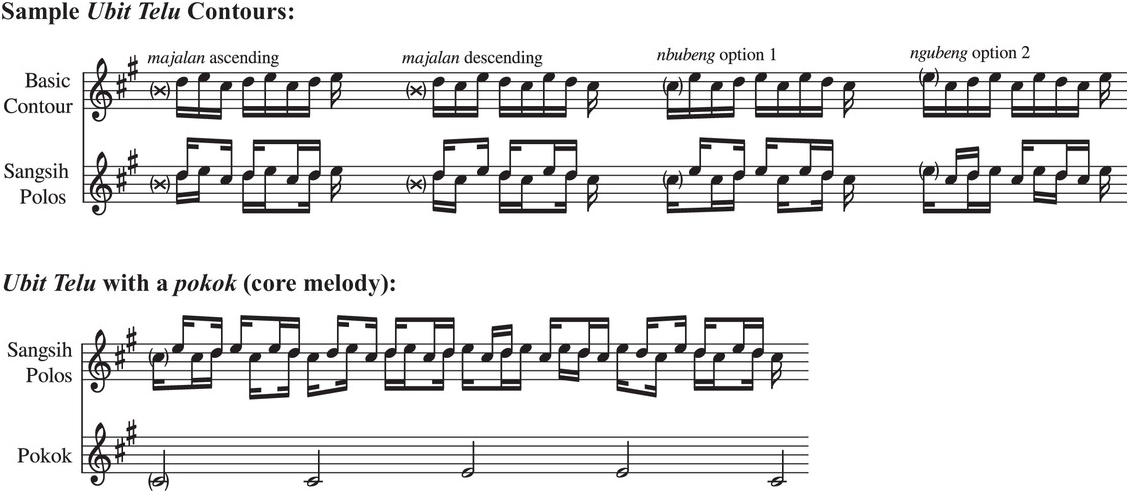

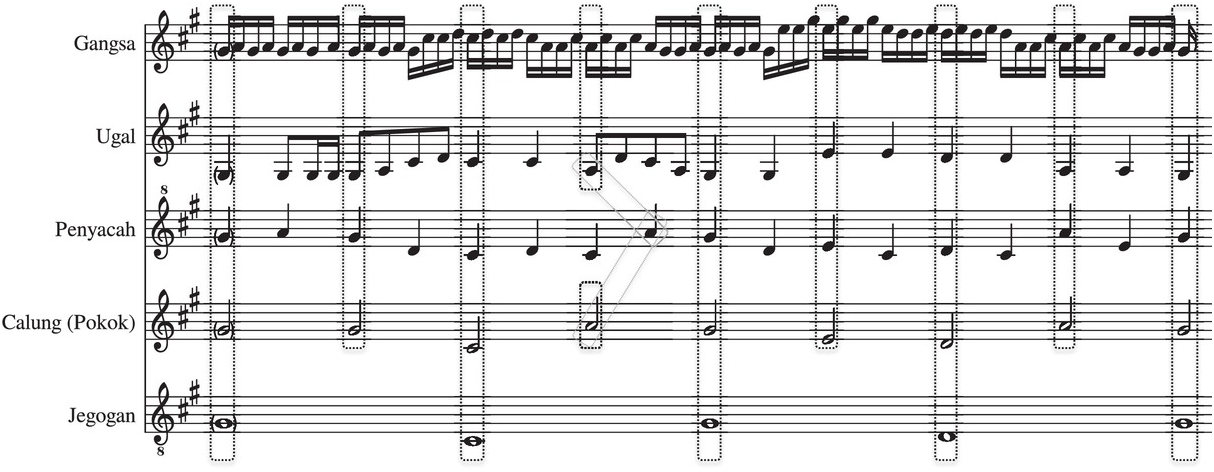

Tala

The remarkable facility in rhythmic play demonstrated by musicians and dancers throughout the Indian subcontinent is as impressive as it can be bewildering for the listener. From local and regional practices, through devotional and popular genres, to the heavily theorized concert traditions of the North (Hindustani music) and South (Karnatak music), rhythmic complexity abounds. A performance may begin without even a pulse, where melodies seem to float unpredictably in musical space. Yet increasing rhythmic regularity leads to the establishment of repetitive sequences of beats, both evenly and unevenly distributed, which provide the frameworks for elaborate melodic and rhythmic compositions, variations, and improvisations. The entrance of drums – also essentially melodic in their subtle manipulations of pitch, timbre, stress, and resonance – is invariably a moment of great visceral as well as intellectual excitement. Together, singers, dancers, instrumentalists, and drummers build their performances around the anchors provided by the beats; they subdivide these beats in myriad ways, playing with different rhythmic densities and syncopations. The thrilling, rapidly articulated sequences with their offbeat stresses can temporarily disorient the listener until all seems to resolve in a triumphant convergence of surface rhythm and target beat. The rhythmic system as a whole and the individual frameworks of beats that serve to organize rhythmic expression are known as tala.

The Sanskrit term tala (Hindi: tal; Tamil: talam) is an ancient concept described in treatises close to 2,000 years old, and still today the word carries the same essential meaning of a handclap. Any attempt to summarize what are arguably the world’s most complex and virtuoso rhythmic-metric practices must necessarily begin with a definition of tala, for it differs from Western meter in a fundamental way. Meter is implicit: it is a pattern that is abstracted from the surface rhythms of a piece, and consists of an underlying pulse that is organized into a recurring hierarchical sequence of strong and weak beats. On the other hand, tala is explicit: it is a recurring pattern of non-hierarchical beats manifested as hand gestures consisting of claps, silent waves, and finger counts, or as a relatively fixed sequence of drum strokes.

The repetitive beat patterns of a tala are often thought of as cyclic, and certain words describing the cycle (avartana, for instance) are based on the Sanskrit root vrt, meaning “turning” or “revolving.” The circular representation shown in Figure 14.1, taken from an Urdu book published in 1869, maps out tintal, Hindustani music’s most prevalent tala of four beats, with each beat lasting four counts for a total of sixteen: it contains quasi-onomatopoeic syllables for the drum strokes (dha, dhin, ta, tin) used to represent the tala. Conceptually, the cycle begins and ends on sama (Hindi: sam; Tamil: samam – here, at the top of the dial), which is the beat representing the most common point of melodic and rhythmic confluence.

14.1 Cyclic representation of tala

Throughout this chapter, readers will encounter many examples of clapped beat structures as well as syllables representing the strokes that articulate rhythms. All are encouraged to engage physically with these phenomena by performing the patterns of claps, waves, and finger counts, and by orally expressing the syllables. For it is through physicality and orality that the musical system is taught. Such an embodiment of tala is crucial not only for achieving rhythmic competence and engendering creativity as a performer but also for deriving enhanced aesthetic pleasure as an audience. Indeed, audience participation through gestures marking tala is prevalent in the concert traditions, especially in Karnatak music, and allows audiences to experience and appreciate more keenly the rhythmic architecture of performance.

Tala in Karnatak Music

As an abstract structure, tala finds its most canonical form in the concert tradition of southern India: Karnatak music. We begin with the example of adi tala: a series of claps, silent waves, and finger counts that provides the framework for roughly 80 percent of songs and other composed works in this repertoire. In Table 14.1, the eight-count sequence of hand gestures provides both visual and sonic markers that allow performers and listeners alike to know precisely where they are within the tala at any given moment. This pattern begins with a clap of the right hand down onto the upturned palm of the left hand on count 1, followed on counts 2, 3, and 4 by taps of the pinky, ring, and middle fingers of the right hand onto the left palm; it continues on count 5 with another clap, and on count 6 with a wave, which is where the right hand turns palm upward and effects either a light tap of the back of the right hand on the left palm or a bounce in the air above it; another clap and wave on counts 7 and 8 conclude the sequence, and the pattern cycles back to repeat from count 1. As stated earlier, the tala has no internal accent structure like Western meter, not even on the clap marking count 1. The gestured 8-count pattern functions to provide a solid temporal reference for complex surface musical activity.

Table 14.1 Clapping structure and solkattu syllables for adi tala

| Counts | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestures | clap | pinky | ring | middle | clap | wave | clap | wave |

| Speed 1 | ta | ka | di | mi | ta | ka | jo | nu |

| Speed 2 | taka | dimi | taka | jonu | taka | dimi | taka | jonu |

| Speed 3 | takadimi | takajonu | takadimi | takajonu | takadimi | takajonu | takadimi | takajonu |

| Triplets | takadi | mitaka | jonuta | kadimi | takajo | nutaka | dimita | kajonu |

A musician trained in a Western tradition might well approach the clapping pattern of adi tala by doing the hand gestures and counting out the eight counts. Yet this approach is rare in South Asia, where musicians tend to use syllabic sequences to mark time rather than numbers. This results in a qualitatively different way of experiencing one’s relationship to the tala. The syllabic sequences are based on solkattu: a rich vocabulary of drum strokes and sounds that are expressed as onomatopoeic syllables like ta, di, tom, and nam. Returning to Table 14.1, we note the presence of eight syllables that should now replace the numbers as one performs the gestures. As a basic exercise, one begins with density level 1, where each hand gesture is accompanied by one syllable. Density level 2 doubles the speed of articulation of the syllables, although one must remember to strictly maintain the original pace of the hand gestures so that now each one is accompanied by two syllables. Density level 3 doubles the speed of articulation yet again, so that four syllables accompany each gesture. These three density levels are known as trikala, the “three speeds,” and all students of Karnatak music, whether melodic or percussive in form, learn this fundamental technique of changing rhythmic densities while maintaining the original pulse. Students of vocal music, for example, proceed through defined sets of scalar exercises sung to the solfège names Sa Ri Ga Ma Pa Dha Ni Sa, all the while clapping adi tala and applying the “three speeds.” As can also be seen in Table 14.1, an additional rhythmic exercise arranges the same syllables in triple time.

Adi tala is fundamentally duple in character, and as such it fits into the first of five classes of rhythm. This first class, or jati, is known as caturasra, or “four sided,” and is commonly articulated with the solkattu sequence ta ka di mi (or ta ka jo nu). As shown in Table 14.2, there are four other jati of 3, 7, 5, and 9 (this is their traditional order), each with its own pattern. The jati are important in several ways: they show how the beat may be internally subdivided into quadruplets, triplets, septuplets, quintuplets, and nonuplets, respectively; they can form the basis for calculating larger units of rhythmic improvisation; and they can serve to modify tala structures. This last point necessitates a brief discussion of the suladi sapta tala system.

The five jati “classes,” the suladi sapta tala system, and some common non-suladi structures

| Caturasra (4) | ta | ka | di | mi | |||||

| Tisra (3) | ta | ki | ta | ||||||

| Misra (7) | ta | ki | ta | ta | ka | di | mi | ||

| Khanda (5) | ta | ka | ta | ki | ta | ||||

| Sankirna (9) | ta | ka | di | mi | ta | ka | ta | ki | ta |

I = laghu: clap plus finger counts

O = drutam: clap plus wave

U = anudrutam: clap

| caturasra (4) | tisra (3) | misra (7) | khanda (5) | sankirna (9) | |

| Dhruva – IOII | 14 | 11 | 23 | 17 | 29 |

| Matya – IOI | 10 | 8 | 16 | 12 | 20 |

| Rupaka – OI | 6 | 5 | 9 | 7 | 11 |

| Jhampa – IUO | 7 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 12 |

| Triputa – IOO | 8 (adi tala) | 7 | 11 | 9 | 13 |

| Ata – IIOO | 12 | 10 | 18 | 14 | 22 |

| Eka – I | 4 | 3 | 7 | 5 | 9 |

Rupaka (3) = clap clap wave

Misra capu (7) = wave wave – clap – clap –

Khanda capu (5) = clap – clap clap –

Appearing first in the late nineteenth century, the suladi sapta tala (seven primordial tala) system quantifies seven basic categories, each with a distinctive gestural structure. The three gestures are laghu (symbol I: a clap plus a variable number of finger counts), drutam (symbol O: a clap plus a wave), and anudrutam (symbol U: a single clap). Adi tala belongs to the triputa category, which comprises one laghu and two drutam. The length of the variable laghu is determined by one of the jati categories: in the case of adi tala, the clap is followed by three finger counts for a total of four counts, and thus the laghu is “four sided.” Another, more cumbersome name for adi tala is therefore caturasra jati triputa tala. As can be seen in Table 14.2, the combination of seven tala categories with the five jati results in thirty-five distinctive tala structures, from three counts up to twenty-nine. What is interesting is that adi tala is not the only structure comprising eight counts, and yet tisra jati matya tala (clap pinky ring clap wave clap pinky ring) and khanda jati jhampa tala (clap pinky ring middle index clap clap wave) differ markedly in their arrangements of gestures.

In truth, however, very few of the thirty-five structures have been employed in performance practice, though one does occasionally hear uncommon tala structures used for exercises and technically challenging showpieces called pallavi that are designed to demonstrate technical virtuosity. The vast majority of compositions, including those of the greatest composers from the Golden Age of Karnatak music in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries – the so-called “Holy Trinity” of Tyagaraja, Diksitar, and Syama Sastri – are set in just four tala: adi tala plus three that do not even belong to the suladi sapta tala system. These are also given in Table 14.2 and comprise only claps and waves: rupaka (3 counts), misra capu (7 counts), and khanda capu (5 counts). These structures are very likely to have entered the concert tradition from local or regional practices. Rupaka is an interesting and somewhat confusing case, as it shares its name but not its structure (clap clap wave) with one of the seven suladi categories (comprising one drutam and one laghu), and it also appears to be a relatively modern substitute for the ancient tisra jati eka tala (clap pinky ring). In practice, rupaka and tisra jati eka tala are interchangeable, and musicians choose according to the teaching lineage through which they have acquired their knowledge.

Rhythmic Play in Karnatak Music

The performance of a typical piece of Karnatak concert music begins with alapana, which is an exposition of the melodic motivic characteristics of a raga without tala. Although the melodies may seem to be free of any regular sense of rhythm, many musicians insist that they are mindful of an underlying pulse against which melodic expression is measurable. Alapana is often quite short, but nevertheless the expanding range of melodic motifs is complemented with increased surface rhythmic density.

Following the alapana is the composition, a text set to melody (or an instrumental rendition of one) that is always framed by a tala and thus always accompanied by a drum. The great percussion instrument of Karnatak music is the mridangam, a barrel drum with two heads made from layers of animal hide, laced together, and capable of being tuned by means of a permanent black compound applied as a low, circular mound in the center of the right head and by the application of a temporary ball of dough stuck and flattened onto the left. While the left head provides a deep, resonant bass, the right produces a variety of timbres depending on how and where the fingers and palm strike it. As the first strains of the melodic composition are delivered, the mridangam player must quickly identify the tala and the tempo, which then remain constant throughout the piece. The starting point for the melodic composition may occur anywhere in the cycle and could even begin on a half beat. Experienced drummers will likely know many compositions and may even play along with some of the prominent rhythmic signatures of the melody. As an accompanist, the drummer’s role is to support the melodic unfolding of the composition, mark the ends of sections of the exposition with rhythmic cadences, and contribute to the increasing energy and intensity of sections of improvisation that follow.

The rhythmic patterns played by the drummer fall into two categories: those that structurally maintain the flow of time, and those that disrupt it through rhythmic formulas that are calculated to terminate on a target beat within the tala, most commonly sama. The first category is known as sarvalaghu (from Sanskrit words implying “all short/easy”). Table 14.3 outlines a few simple examples of sarvalaghu, each of which the reader is encouraged to read out loud while clapping the structure of adi tala. These patterns have a tendency toward internal repetition that subdivides them into two halves and thus reinforces the repetitive groove resulting from the distinctive timbres and articulations. The groove takes on a particularly heavy swing in examples 4–7 (for instance, in example 5 one should sharpen the attack on TAka and exaggerate the weighty resonance of JOnu), and example 8 suggests greater surface rhythmic density, pointing toward patterns that become increasingly complex as pieces develop. Once one has gained familiarity with these patterns, one should double their speed to get a sense of how they sound in performance (yet maintain the original tempo of the clapping pattern – a metronome mark of roughly 84 counts per minute is a fairly typical performance tempo). A drummer will switch between many different sarvalaghu patterns according to the flow and rate of activity of the melodic exposition and its development.

Table 14.3 Sarvalaghu patterns in adi tala

| clap | pinky | ring | middle | clap | wave | clap | wave | |

| 1 | ta | din | din | na | ta ka | din | din | na |

| 2 | ta | din | ta ka | din | ta | din | ta ka | din |

| 3 | ta | din | ta | din | ta ka | din | tom | kita taka |

| 4 | ta ka | di mi | ta ka | di mi | ta ka | di mi | ta ka | di mi |

| 5 | tam | – ki | ta ka | jo nu | tam | – ki | ta ka | jo nu |

| 6 | tam | – ki | ta ka | jo nu | ta ka | tom ki | ta ka | jo nu |

| 7 | din din | din tom | – ta | din na | din din | din tom | – ta | din na |

| 8 | tom | kita taka | taka din | kita taka | tom | kita taka | taka din | kita taka |

The second category is known as kanakku, “calculation,” which is a vast and complex topic too large for anything but a cursory introduction. We shall briefly look at endings (mora), shapes (yati), and complex designs (korvai). All are configured in such a way as to create temporary uncertainty only to find familiar ground once again by directing our attention to a target beat. The simple examples given in Table 14.4 are borrowed from David Nelson’s exemplary Solkattu Manual.1

Table 14.4 Mora, yati, and korvai

| 1. Mora | ||||

| Structure: (statement) + [gap] + (statement) + [gap] + (statement) | ||||

| Statement: (ta ta kt tom tom ta) = 6 pulses | ||||

| Gap: [tam – –] = 3 pulses | ||||

| (ta ta kt tom tom ta) [tam – –] (ta ta kt tom tom ta) [tam – –] (ta ta kt tom tom ta) | ||||

| clap ta – din – | pinky din – na – | ring (ta ta kt tom | middle tom ta) [tam – | |

| clap –] (ta ta kt | wave tom tom ta) [tam | clap – –] (ta ta | wave kt tom tom ta) | |

| 2. Yati | ||||

| Gopucca yati | Srotovaha yati | |||

| 6 + 2 (ta ta kt tom tom ta) [tam –] | 1 + 2 (ta) [tam –] | |||

| 4 + 2 (kt tom tom ta) [tam –] | 2 + 2 (tom ta) [tam –] | |||

| 3 + 2 (tom tom ta) [tam –] | 3 + 2 (tom tom ta) [tam –] | |||

| 2 + 2 (tom ta) [tam –] | 4 + 2 (kt tom tom ta) [tam –] | |||

| 1 (ta) | 6 (ta ta kt tom tom ta) | |||

| 3. Korvai | ||||

| a) ta ki ta tom – ta din gi na tom = 10 pulses | ||||

| b) jo nu jo nu = 4 pulses | ||||

| c) tom – ta – = 4 pulses | ||||

| d) tam – – = 3 pulses | ||||

| ta ki ta tom | – ta din gi | na tom jo nu | jo nu tom – | |

| ta – tam – | – ta ki ta | tom – ta din | gi na tom jo | |

| nu jo nu tom | – ta – tam | – – ta ki | ta tom – ta | |

| din gi na tom | jo nu jo nu | tom – ta – | tam – – jo | |

| nu jo nu tom | – ta – tam | – – jo nu | jo nu (tom – | |

| ta –) [tam – | –] (tom – ta | –) [tam – –] | (tom – ta–) | |

A mora is a rhythmic cadence that ends a section of the music. In its simplest form, it is a sequence of strokes that is played three times: the reason for three statements of a given pattern is important. With just two statements, it would be difficult to anticipate the target beat, whereas with three, the pattern is not only more firmly established in the listener’s mind but also the temporal distance from the second to the third can be predicted to be the same as from the first to the second. The mora shown in Table 14.4 features the pattern ta ta kt tom tom ta tam, which covers 7 pulses (kt stands for kita and occupies 1 pulse). The body of the pattern is the 6-pulse statement ta ta kt tom tom ta, and tam is its end point. Tam may be followed by no gap at all, or more commonly with a gap of a variable number of pulses. In this case, tam is followed by a 2-pulse gap for a total of 3 pulses: tam – –. The mora, then, comprises (statement) + [gap] + (statement) + [gap] + (statement) for a total of 24 pulses. If the rate of rhythmic action in adi tala is 4 pulses per count, then the 8-count cycle will comprise 32 pulses. It follows, therefore, that in order to target the sama of the cycle on count 1 the mora should start after a gap of 8 pulses (in this case, those pulses are occupied by part of a sarvalaghu pattern from Table 14.3, ta – din – din – na –); in other words, the mora begins on the third count that is marked by the ring-finger gesture.

Yati refers to a series of operations that create shapes in the mind of the listener. The truly interesting ones among them are the cow’s tail (gopucca) and the river mouth (srotovaha), which represent narrowing and expanding operations, respectively. Retaining the same statement used for the first mora, we can see in Table 14.4 how elements are subtracted from the original phrase in gopucca yati, while the reverse is true in srotovaha yati. The gap in each instance is reduced to 2 pulses [tam –], and once again the total number of pulses for each sequence is 24. Therefore, these mora also begin on the third count of adi tala. By combining these two shapes, one can create two more: damaru yati (a small hourglass-shaped drum) with gopucca-srotovaha, and the barrel-shaped mridanga yati with srotovaha-gopucca.

In accompaniment, the mridangam player tends toward shorter, simpler mora structures. Yet often near the end of a concert piece the spotlight may shift over to the drummer for a solo that can run anywhere from two to ten minutes. This is the tani avartanam, and it marks a special moment of great concentration for the other performers on stage who attempt to maintain the clapping pattern of the tala as the only accompaniment to the sounds of the drum. Here the rhythmic designs are longer and more complex, and may involve changing the surface rhythmic density from duple to triple time, or even to quintuplets and septuplets. Compound mora structures are also increasingly likely, where a mora is repeated three times, thus prolonging the tension before a resolution on the sama of the cycle. But the tani avartanam must also have at least one grand, pre-composed structure: the korvai.

A korvai may feature all manner of clever rhythmic thinking, but at root it comprises a yati plus a mora. In the relatively simple example given in Table 14.4, there are four phrases of 10, 4, 4, and 3 pulses, respectively, which create the narrowing shape of gopucca yati. The composition repeats phrases abcd three times, then bcd, then b, and finally the mora statement and gap constructed from (c)+[d]+(c)+[d]+(c). A korvai may in fact be extensive, combining many sections, as long as it ends with a mora. They are often difficult to execute, and difficult to follow, but they represent the pinnacle of arithmetic thinking merged with musical aesthetics and technique, and they are quite thrilling to experience.

Finally, one may sometimes find more than one percussion instrument on stage in a Karnatak music concert, most commonly a ghatam (clay pot) and a khanjira (small tambourine). These are wielded with extraordinary technical skill, and are capable of replicating anything the mridangam can do.

A Brief Word on Local and Regional Rhythmic Traditions

There exists an extraordinary diversity of approaches to rhythm in South Asia, yet outside the concert traditions of Karnatak and Hindustani music there is relatively little detailed documentation or analysis of how precisely rhythm works. Certain scholars have unearthed evidence contradicting the notion that rhythm in South Asia is rigidly organized into isometric, that is, unchanging cycles of beats and counts. Jim Sykes2 has described Sinhala Buddhist ritual music in Sri Lanka where drumming patterns can sound like unmetered speech, where long and short drum syllables set in lines of drum poetry often do not coincide with beats or pulses, and where sometimes the beats may even be stretched to match the durations of drum words. Without an insider’s understanding of the rhythmic logic of the drums in these ritual contexts, these irregular cycles and rhythms are difficult or impossible to count. Richard Widdess3 has noted how in many older repertoires of religious genres – such as Sikh gurubani hymns in the Punjab, Sufi devotional qawwali songs from Delhi, temple traditions from Lord Krishna’s heartland of Vrindaban, and religious and ceremonial music and dance among the Newar of the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal – heterometric rhythmic organization survives alongside isometric structures, and may have been (or indeed may still be) far more widespread that we realize. In a heterometric composition, the tala changes from section to section of the piece, unlike the concert traditions where the tala changes only if the composition does. In his work with Shi’a drumming groups active during Muharram (the annual period of mourning) in Muslim centers across India and Pakistan, Richard Wolf 4 also documented examples of heterometric structure. Additionally, in his study of Kota tribal drumming from South India,5 he introduced the important analytic idea of beats as anchor points that act as signposts that are especially important in coordinating group rhythmic practices. The spaces between beats can be flexible through non-uniform inflation, just as they are in the Karnatak system where the variable laghu can expand from 3 to 4, 5, 7, or 9 counts. Indeed, the rationale for many of the observations Wolf has made about a wide array of drumming practices focuses on the importance of the number of beats – both as a series of foundational anchors and also as stressed strokes in a surface rhythmic pattern – in the naming and identification of a tala. Of course, not all carry the name tala: though the term is widespread, others like cal (Hindi: “motion; gait”) or ati (Tamil: “beat”) are also found, and some traditions appear to have no word for tala at all.

One other very important analytic concept introduced by Richard Wolf is “stroke melody.” This resonates with what I wrote earlier about the extraordinary variety of different pitches, timbres, and articulations that drummers can produce on their instruments, either solo or in ensembles featuring several different kinds of membranophones and idiophones (small cymbals, for instance, that have always traditionally marked anchor points). Stroke melodies are prominent throughout South Asia, and are fixed patterns whose combinations of timbres and stresses set up what might best be described as a groove: a repetitive rhythm rooted in bodily movement that often involves offbeat stresses and that conveys a feeling of motion (compare the Hindi term cal). They often establish an underlying framework for other musical activity, and sometimes through variation, expansion, and changes in density they can be the focus of the musical performance itself. As we shall see, stroke melodies are also very important in the Hindustani concert tradition.

Hindustani Tala

The Hindustani tala system in fact harbors two systems that over the past two centuries have become enmeshed to such an extent that few would acknowledge any separation whatsoever. Yet extricating one from the other can prove instructive. The first lies within the domain of dhrupad: widely considered to be the oldest genre still performed, a dhrupad performance features a substantial unaccompanied alap (compare this with alapana), followed by one or two compositions set in tala and accompanied by a barrel drum called either pakhavaj or mridang (compare this with mridangam, to which it is structurally similar). The second pertains to all other types of concert music: vocal genres such as khayal, thumri, and so on; instrumental music of the sitar, sarod, and so on; and the dance form that during the twentieth century came to be known as kathak. All these genres are accompanied by the tabla, which along with the sitar has become a globally recognized symbol of Indian music.

Of the hundreds of tala structures that have been listed over the centuries in Sanskrit and Indo-Persian treatises, only four continue to appear with any regularity in the modern dhrupad repertoire. Of these, cautal and dhamar (12 and 14 counts, respectively) dominate slow-tempo compositions, and sultal and tivra (10 and 7 counts) frame those in fast tempo. Matra (etymologically linked to meter) is the commonly used word for a count: in the past, the matra corresponded to a healthy human pulse, but it is now conceived as a flexible unit dependent on tempo: laya. In the three categories, slow, medium, and fast (vilambit, madhya, drut), the matra can range from 12 per minute in the case of slow khayal compositions up to 720 in ever-accelerating instrumental climaxes.

Table 14.5 maps the beats of tala structures for dhrupad using only clap and wave gestures: unlike Karnatak tala, finger counts are not generally used, and certainly not systematically so. What dhrupad has in common with Karnatak practice, however, is the strict maintenance of the clapping pattern by performers and audience as an external representation of the tala in use, which in turn frees the pakhavaj player to support the melodic unfolding of the composition, mark the ends of its sections with rhythmic cadences, and contribute to the increasing energy and intensity of the performance – as is precisely the case with the mridangam player. Moreover, just as the mridangam player may choose from various sarvalaghu patterns to fill the tala cycle and contribute to rhythmic flow, the pakhavaj player too adopts repetitive, groove-like patterns. The first examples were notated in the early 1850s by Wajid Ali Shah, king of Awadh, a lavish patron and practitioner of music at his court in Lucknow. He called them theka, “accompaniment.” A theka is a fixed sequence of drum strokes that, when repeated relatively unchanged cycle after cycle, creates a recognizable representation of a tala – an aural symbol of it – and thus its presence largely obviates the need for the clapping pattern to mark time. However, Wajid Ali Shah’s theka for cautal would in subsequent years be interpreted merely as a kind of filler pattern akin to sarvalaghu, and was superseded in the late nineteenth century by another pattern that even today continues as the established theka representing cautal. The paradox is that in spite of the presence of these theka patterns, there is still a heavy reliance on external clapping patterns for dhrupad and pakhavaj performance. By contrast, clapping in non-dhrupad genres is rare. This raises three points: (1) that dhrupad and Karnatak performance are less removed from one another than is generally assumed; (2) that the pakhavaj accompanist spends very little time playing theka but rather quickly shifts gears into filler patterns and compositions, thus creating the need for an external set of markers for the tala; and (3) that theka is probably not native to the pakhavaj but instead owes its presence to the influence of the tabla. Theka is first linked to tabla in texts from the early nineteenth century.

Table 14.5 Tala structures for dhrupad

First appearing in the early eighteenth century, the tabla was, organologically speaking, a pakhavaj split into two parts and played with skins facing up. The substitution of a small hemispherical kettledrum for the bass gave drummers the ability to create extremely active pitch inflections of its resonant sonority, allowing it to replicate not only the rhythmic language of the pakhavaj but also that of the barrel drum dholak, widely used in local and regional musical genres as well as in the traditions of the Qawwals, who sang Muslim devotional genres as well as khayal, among other things. It was this flexibility that led to a growing preference for tabla in all genres other than dhrupad, but the drum owed its rapid spread throughout northern parts of the subcontinent to the popular songs and dances of female entertainers. Such performances were labelled “nautch” by the British (a corruption of nac, “dance”), and were very much the rage in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries among Indians and foreigners alike.