Introduction

Culture, which can be defined as the way people do things in any given setting (Williams, Dobson, & Walters, Reference Williams, Dobson and Walters1994), has ramifications in organizational contexts. Culture encompasses the values, beliefs, norms, customs, traditions and religious foundations that underpin social groups at national, regional, local or organizational levels (Marković, Reference Marković2012). While national and organizational cultures differ, they are nevertheless interrelated and interconnected. Culture influences politics, leadership, management, sustainability, economy and religion (Caligiuri, Reference Caligiuri2013; Toh & Leonardelli, Reference Toh and Leonardelli2013; Pathak & Perera, Reference Pathak and Perera2017). For these reasons, this research is important, timely and relevant to management and organization studies. Although this research focuses on Australian Muslim organizations (AMOs), the findings could be applicable to nations with similar multicultural populations.

Although Australia's national macro-culture is British or Anglo-Celtic in origin (Forrest & Dunn, Reference Forrest and Dunn2006), the nation embraced multi-ethnic waves of migration after World War 2. Coupled with the recognition of the First Peoples of Australia, these waves of migration have changed the sociocultural dynamics of Australia, with population becoming increasingly multicultural. Multiculturalism in Australia is viewed as a source of strength, pride and as a strategy for national competitiveness (Ng & Metz, Reference Ng and Metz2015). Australian Muslims are an important multi-ethnic group in Australia, comprising 2.6% of the Australian population according to the 2016 Census (ABS, 2018). Australian Muslims are not homogeneous group; rather there is considerable diversity in terms of national and regional cultural heritage and denominational affiliations. This diversity has an impact on the multicultural complexity of Australian society and on organizations operating within this society. This paper intends to highlight the complex notion of culture in relation to leadership in the Australian Muslim organizational context.

The macro-culture in which organizations are embedded plays an important role in organizational culture and management. Ajibade, Chima, and Osabutey (Reference Ajibade, Chima and Osabutey2017), while investigating the impact of organizational culture in highly stressful Nigerian work environments, concluded that both organizational culture and national culture strongly influences employees’ use of work–life balance policies. In another organizational study involving 21 countries, Peretz, Fried, and Levi (Reference Peretz, Fried and Levi2018) found that national cultural values influenced absenteeism and turnover in organizations using flexible work arrangements. The broader macro-culture is therefore significant to the organizational culture.

Organizational culture relates to employee commitment. A study (Simosi & Xenikou, Reference Simosi and Xenikou2010) indicates the existence of a moderate but significant association between the content of organizational culture and employees’ commitment. In addition, Dwivedi, Kaushik, and Luxmi (Reference Dwivedi, Kaushik and Luxmi2014) while investigating the impact of organizational culture on commitment of employees in the Indian Business Process Outsourcing industry, concluded that six dimensions of organizational culture namely, proaction, confrontation, trust, authenticity, experimentation and collaboration are positively related to organizational commitment. Employee commitment is necessary for any organization in terms of motivating employees and sustaining productivity.

Empirical research clearly shows that organizational values have a strong influence on managers’ competencies (Gorenak & Ferjan, Reference Gorenak and Ferjan2015) and on organizational culture. One competency of an importance is achieving organizational goals. Den Hartog and Verburg (Reference Den Hartog and Verburg2004) and Huhtala, Feldt, Hyvönen, and Mauno (Reference Huhtala, Feldt, Hyvönen and Mauno2013) found that managers who evaluated their organizational culture as more ethical were more likely to report organizational goals, subsequently leading to high performance work systems and firm performance.

Despite the well-established evidence-based research that shows the impact of leading and managing on organizational culture (Schein, Reference Schein2010; Khilji, Keilson, Shakir, & Shrestha, Reference Khilji, Keilson, Shakir and Shrestha2015; Krapfl & Kruja, Reference Krapfl and Kruja2015), and subsequently its importance to organizational work, there is a lack of evidence on how national or regional macro-cultures and sub-cultures impact leading and managing (Manzoor, Reference Manzoor2015; Vandayani, Reference Vandayani2015; Ünal, Bjerke, & Daudi, Reference Ünal, Bjerke and Daudi2017). Summarizing leadership in different cultures, Munley (Reference Munley2011) argues that ‘The globalization of many organizations and the increasing interdependence of nations make the understanding of culture and its influence on leadership increasingly important’ (p. 16). This paper intends to make a contribution to the field of management and organizations by addressing the under-researched issue of the impact of macro-culture and sub-cultures on Muslim leadership in a Western context.

Literature Review: Leadership and Culture

The notion of leadership in Islam encompasses multiple dimensions including individual and leading characteristics (Fontaine, Ahmad, & Oziev, Reference Fontaine, Ahmad and Oziev2017; Faris & Abdalla, Reference Faris and Abdalla2018). At an individual level, leadership in Islam suggests piety, sincerity, patience, kindness, knowledge, wisdom, sacrifice and forbearance. Islam suggests two primary roles for leaders, as a servant and a guardian who executes leadership obligations with justice, consultation, accountability, transparency, openness and effective communication (Beekun & Badawi, Reference Beekun and Badawi1999; Fontaine, Ahmad, & Oziev, Reference Fontaine, Ahmad and Oziev2017).

The notion of leadership in Australia is not dissimilar to conventional leadership in other Western countries and essentially encompasses servant, authentic, ethical, charismatic and pragmatic type of leadership (Fontaine, Ahmad, & Oziev, Reference Fontaine, Ahmad and Oziev2017).

There is no shortage of research on the impact of leadership on organizational culture and the role of leadership in different macro-cultural settings (Earley, Reference Earley1999; Graen & Hui, Reference Graen, Hui and Mobley1999; Ardichvili, Reference Ardichvili2001; Dastmalchian, Javidan & Alam, Reference Dastmalchian, Javidan and Alam2001; Schein, Reference Schein2010; Khilji et al., Reference Khilji, Keilson, Shakir and Shrestha2015; Krapfl & Kruja, Reference Krapfl and Kruja2015). Leadership has long been viewed as the primary factor in shaping organizational culture. Schein (Reference Schein2010), for example, emphasizes the important role of leadership in identifying, understanding, establishing, modifying and maintaining organizational culture. The characteristics and strengths of a leader can create a supportive and strong organizational culture (Krapfl and Kruja, Reference Krapfl and Kruja2015). Indeed, Krapfl and Kruja (Reference Krapfl and Kruja2015) suggest that organizational cultures are influenced by the leader more than any other single factor. In their recent empirical investigation, Khilji et al. (Reference Khilji, Keilson, Shakir and Shrestha2015) provide evidence for transformational authentic leaders in South Asia who are engaged with followers and are building authentic cultures for positive organizational outcomes.

On the other hand, research that investigates the impact of the national macro-culture on leadership, while still limited, is gaining momentum (Qureshi, Zaman, & Bhatti, Reference Qureshi, Zaman and Bhatti2011; Manzoor, Reference Manzoor2015; Vandayani, Reference Vandayani2015; Ünal, Bjerke, & Daudi, Reference Ünal, Bjerke and Daudi2017). These studies investigated the impact of national culture and indigenous culture on leadership. Available evidence suggests that different macro-cultures have different impacts upon leadership (Theimann, April, & Blass, Reference Theimann, April and Blass2006). A study of Theimann, April, and Blass (Reference Theimann, April and Blass2006) on the African context suggests that, for a management system to operate successfully, it must take account of the cultural milieu in which the organization is seeking to operate. The Australian Muslim context, which is characterized by cultural diversity, could be a fertile ground to improve our understanding of the dynamics of culture and leadership within predominantly Western societies.

As mentioned previously, Islam in Australia encompasses multiple sects, sub-sects and offshoots. Muslims in Australia are divided between two main sects: Sunni and Shiite. Sunnis have four schools of thought (jurisprudence) and different ideologies of moderates and fundamentals. The Shiite sect is also divided between a few schools of thoughts and Taqleed (i.e., the practice of following certain Imams). Although the offshoots are few, they still maintain a notable presence in Australia through the Druze, Baha'i and Ahmadis. Of the total Australian Muslim population, 53% are males and 47% are females (ABS, 2017a).

In addition to religious subdivisions, Australian Muslims differ in their ethnic and cultural background. The latest Australian census shows that more than one-quarter (26%) of all overseas-born Muslims came from Southern, South-eastern and Central Asian countries, with the remainder coming from North and Sub-Saharan Africa, Middle East and Europe (ABS, 2017b).

Australian Muslims do not live in a vacuum separated from the broader Australian society. Active participation within Australian society guided early Muslim leaders in their establishment of their own organizations (Faris & Parry, Reference Faris and Parry2011). Muslim organizations cater for the social, religious, educational and political needs of Australian Muslims. The first Muslim political party in Australia was established in late 2015 giving Australian Muslims a formal mechanism to represent their views and their values (Aston, Reference Aston2015). As with other minority groups, some Australian Muslims feel social isolation, marginalization, discrimination and even vilification. Furthermore, it is widely observed that there is a distorted view of Islam in the language used by some Australian politicians when they address the broader community on issues related to Islam and Muslims (Yasmeen, Reference Yasmeen2010).

In addition to these challenges, Australian Muslims are characterized by great diversity. Within this complex context, the practice of leadership can be problematic. In particular, the variation in perceptions and attributions inherent at this level of diversity mean that sense-making is problematic for anyone attempting to demonstrate leadership. Sense-making is axiomatic to the nature of leadership (Parry, Reference Parry1999; Pye, Reference Pye2005).

Muslims in Australia and in the West in general struggle with integration, inclusion–exclusion, hybrid culture, cultural adaptation, islamophobia and paradoxical identity (Yasmeen, Reference Yasmeen2010; Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2011; Busbridge, Reference Busbridge2013; Collins, Reference Collins2013; Adida, Laitin, & Valfort, Reference Adida, Laitin and Valfort2016). A summary of these cultural definitions is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Cultural concepts and definitions

Diversity among Australian Muslims in a multicultural society adds to the challenges of cultural adaptation and to issues of identity. While some Australian Muslims consider that their culture and identity are incompatible with the Australian national culture and identity, others disagree (Yasmeen, Reference Yasmeen2008; Donelly, Reference Donelly2016). Cultural, sub-cultural and identity differences are important and relevant, and pose challenges to the Australian Muslim community and their leadership. The degree to which these challenges affect Australian Muslim leadership remains to be tested, hence the development of our research question.

Research question

How does leadership operate across cultures within the Australian Muslim context?

This research question explores leadership within a complex-multicultural setting. The comparative minority status of Muslims in Australia, coupled with the heterogeneity of the Muslim population, renders the challenge of leadership potentially problematic. More specifically, leadership appears to be constrained in certain multicultural contexts.

We could also ask how leadership practice might need to vary across such a complex cultural setting. Attempts to answer this question might result in very complex and confusing answers. Therefore, instead, we decided to pose this question in reverse; by asking for the level of similarity of leadership, the level of variety might become apparent.

In the remainder of this paper, we explain the methodology, data gathering and procedures of data analysis employed. The findings are presented, followed by discussion of the ‘iron cage’ of organizational cultural complexity. We respond to the research questions, and offer remarks, suggestions and policy implications before summarizing in the conclusion.

Methodology

This research did not involve theory testing. Rather, a qualitative theory-emergent research methodology and reflexive and subjective auto-ethnographic assessment of the phenomena were conducted. Data were triangulated from three different qualitative sources and analysis was qualitative. Core categories and processes emerged during the concurrent processes of data gathering and analysis.

Participants and sampling approach

The researchers had prior connections with key informants (Bernard, Reference Bernard1995) who identified potential research participants. Participants were, in some cases, affiliated with specific Islamic organizations: the Australian National Imams Council (ANIC) or the Australian Federation of Islamic Councils (AFIC). The researchers contacted the potential participants on an individual basis, explained the research and sought their voluntary participation in research interviews and/or focus groups. Essentially, the participant selection began with purposive sampling before moving to theoretical sampling (Glaser, Reference Glaser1978; Jeon, Reference Jeon2004; Tuckett, Reference Tuckett2004) as the coding and fine tuning of our categories progressed. There was considerable diversity in the demographics of the participants, as indicated in Table 2.

Table 2. Participant demographics

Data gathering

Unstructured interviews and focus groups formed the basis of data gathering. One researcher participated in some of the organizational activities while observing and conducting unstructured casual interviews. One researcher is an immigrant Muslim and the other is a 4th generation Christian. This combination helped maintain impartiality when analyzing and categorizing data. Interviews and focus groups were conducted in English, face-to-face or by phone, and were audio captured. Each interview and the focus group audio-recording was transcribed and anonymized prior to analysis. Data collection occurred over 3 years, from 2013 until the beginning of 2016.

Interviews

Interviews lasted for half an hour to 1 hr on average. Because all were willing and enthusiastic participants in the research, they were able to provide very rich data. The interviews generally followed a pre-prepared schedule with follow-up questions as advocated by Parry (Reference Parry1999). These questions asked about a range of incidents and experiences encountered by respondents.

Focus group

Focus groups facilitate interaction among participants and maximize the collection of high quality information in limited time (Acocella, Reference Acocella2012). A single focus group discussion was conducted with some participants to probe specific research concerns that had not been resolved through the extant theoretical sampling and coding. The focus group meeting also helped to confirm the properties of the emerging categories. The participants were knowledgeable and forthcoming with their insights (see Appendix).

Documents

Documents are considered one of the prime tools of social research (Plummer, Reference Plummer2004). Within this research, document collection and analysis was undertaken in conjunction with other data collection. The documents consisted of newsletters, mission statements, policy implementation memorandums, newspaper articles and other forms of news media that cover Muslim organizations deemed active in Australia, including the organizations under investigation and other relevant organizations such as the Lebanese Muslim Association.

Analysis

Data analysis was conducted concurrently with the gathering of data. Documentary analysis was ongoing, in order to elaborate the contextual setting within which the research takes place. Theoretical sampling progressively enhanced the utility of the data. The data sources assisted the triangulation of data, which helped to improve the validity of the findings, as advocated by Merriam (Reference Merriam2002). Interviews were recorded and transcribed, allowing both researchers to take notes and guide subsequent interviews into areas of interest in more depth. Both researchers reviewed memos and transcripts immediately, to determine the themes that emerged from the narratives and to determine the direction of the next data gathering episode.

The unit of analysis for the coding gradually shifted from words or phrases to thoughts, behaviors and processes, subsequently building themes and categories. Several core elements of grounded theory were employed, although we cannot claim that this is a grounded theory project. Grounded theory coding methods were used to analyze our data. Open coding and axial coding (Strauss & Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1998) helped to identify the most important categories. Theoretical coding (Glaser & Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967; Glaser, Reference Glaser1978) helped us to identify the higher-order categories that emerged. There were several iterations of theoretical coding. Emergent categories were compared constantly with the existing categories. Constant comparison (Glaser & Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967) meant that each collection of data was coded and categorized before the next gathering of data.

Theoretical sampling (Glaser & Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967; Glaser, Reference Glaser1978) helped us to engage in several iterations of data gathering and analysis so that the emerging explanation was as valid and reliable as possible. It also helped us to gather data that were as rich and explanatory as possible, rather than merely accessing a potentially representative sample of a population. Working together, the researchers engaged in reflexive and subjective auto-ethnographic assessment of these phenomena, as advocated by Alvesson (Reference Alvesson1996) for leadership studies. As identified by Parry and Boyle (Reference Parry, Boyle, Buchanan and Bryman2008), the personalized and emotive nature of the reflexive approach to these phenomena made for a richer and more plausible interpretation of the emerging theory. Kempster and Stewart (Reference Kempster and Stewart2010) demonstrate that auto-ethnographic research is gaining greater leverage in business and management research.

All analysis was assisted by the use of NVivo 10 software (Richards, Reference Richards2005). This qualitative analysis software enables data to be tracked with ease and is capable of building robust concept models. We used the NVivo 10 software to establish the validity of our assessment by using auto-coding tools. In the spirit of a critical realistic approach to qualitative research (Kempster & Parry, Reference Kempster and Parry2011), data from the final stages of analysis were returned to participants alongside illustrative quotes and they were asked to comment on whether the results resonated with their experiences to help determine their plausibility and practical adequacy (Creswell, Reference Creswell2007; Doyle, Reference Doyle2007). University ethics protocols were followed throughout.

Findings

Four main themes emerged from our analysis of the interviews and focus group discussion: (1) the role of the Australian macro-culture; (2) the role of Islam; (3) the role of organizational culture and (4) cultural complexity. Cultural complexity included the sub-categories of ethnocentric thinking, negligence and leadership identity struggle.

The role of the Australian macro-culture

Those Muslims who did not have a strong ethnic, national and/or sectarian allegiance reported that mainstream Australian culture played a large role in shaping their understandings of leadership. These second generation Australians and Australian-born Muslims are highly exposed to the norms and values of the wider Australian society. This cross-cultural context provides fertile ground for a new construction of Islam, which influences expectations of leadership. Australian society exposes Muslims to Western values, and it also brings them into contact with Muslims from other ethnic backgrounds. The cross-cultural experience gives the new generation of Australian Muslim leaders’ confidence to be actively involved in organizational work. While Australian-born Muslim leaders are still few in number, they emphasize active participation in the wider Australian society while, maintaining the view that Islam has something distinctive to contribute to traditional understandings of justice, morals and values.

Several contemporary organizational leaders are second and third generation Australian Muslims who have participated fully in Australian life. They have had a deep level of interaction with the wider community, and they clearly think of themselves as Australian Muslims. However, recent Muslim migrants who came from several different countries and cultures are still grappling with Australian society, culture and organizational work. Their understanding of leadership is confusing and, at times, at odds with Australian culture. Therefore, it is not surprising to find considerable variation in these respondents’ understandings of the connection between Australian culture and their previous home culture.

Representative quotes for the theme role of the Australian macro-culture are provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Role of the Australian macro-culture: illustrative quotes

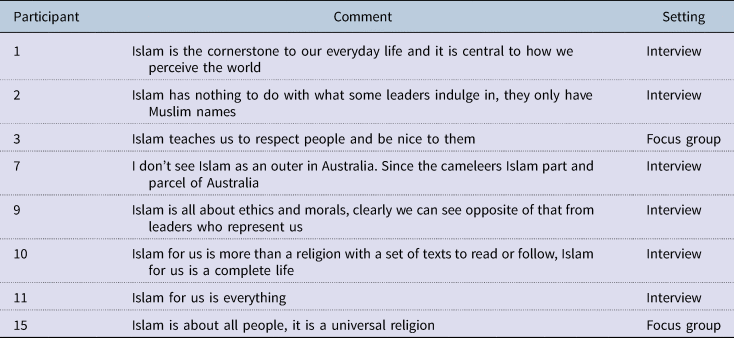

The role of Islam

The strong role of Islam is somewhat unique to this research. For Muslims, Islam is a way of life. This can add a further level of complexity to life in an Australian setting. The findings of this study indicated that Islam was a central theme in the lives of these participants. For them, Islam is more than a religion with a set of texts to read or follow. Islam for them is complete life. Islam encourage Muslims to adhere to the best of values, morals and behaviors, abstain from bad attitudes, treat people with dignity and respect, deal with people in fairness, consult in every capacity, show courage when admitting mistakes and to accept responsibility. While these are prime core of Islamic insights, adherents to these rules are yet to be seen within AMOs.

Imams and intellectual leaders are integral to Islam in the Australian Muslim context. Intellectual leaders include highly educated academics who provide valued guidance for a generation of Australian Muslim youth. Intellectual leaders in general are ‘down-to-earth’ and maintain very close relationships with young Muslims who value their knowledge and experience.

Imams represent the most direct manifestation of leadership for Australian Muslims. These religious leaders offer theological and Islamic cultural guidance on most aspects of Muslim daily life. Imams lead everyday prayers and give advice on a weekly or even daily basis to people whenever that help is sought or needed. Imams are usually appointed by local communities to lead the local Mosques but they have minimal say on how these local communities govern and conduct their affairs. The impact of individual Imams depends on their knowledge and expertise and their say on the affairs of their Mosques. Most of the Imams around Australia studied and trained overseas due to the lack of Australian Muslim institutions who can offer the required theological Islamic knowledge. Overseas training for Imams can provide contradictory messages regarding the expectations of Australian culture vis-à-vis the expectations of Islam. These contradictory messages might be confusing to young Muslims in particular.

In their attempt to soften the public negativity about Islam and Muslims and to engage with the wider Australian community, Imams, in collaboration with the Lebanese Muslim Association and Welcome to Australia,Footnote 1 launched National Unity Week combining both National Mosque Open Day and Walk Together.Footnote 2 The event took full shape in 2015, gathering momentum and was launched by national leaders from across the political spectrum. The aim of this event was to breakdown common misconceptions and stereotypes surrounding Islam (Lebanese Muslim Association, 2017; Welcome to Australia, 2017). The Open Day is a sign of conciliation between the Australian Muslim community and the wider Australian community. It is a gap-bridging exercise whereby the active participation of Imams gives the wider Australian public a glimpse of Islam and helps younger Muslim to reconcile their Muslim identity with their Australian identity. In addition, the majority of Imams are playing a proactive role in generating cross-cultural understanding between Australian Muslims and non-Muslims.

The role of Islam is positive despite some negativity delivered by a few Imams who are the exception and not the norm. Despite the efforts of the vast majority of Australian Imams, data show that their hands are tied in terms of their ability to discuss and talk freely about serious issues. This restriction could inhibit the promulgation of constructive views among Muslims in general and young Muslims in particular. Deep debate about cultural and identity construction appears to be frequently absent from organizational settings, community and Mosques. This absence of debate adds to the dilemma of the young Muslim generation and obviously the broader Muslim setting in Australia. Representative quotes for the theme role of Islam are provided in Table 4.

Table 4. Role of Islam: illustrative quotes

The role of organizational culture

The third major cultural category that emerged in the research was that of organizational culture. Once again, the presence and impact of this category is not surprising. Several competing factors play roles in shaping organizational culture within the Australian Islamic setting. Organizational culture was not detached from the other categories that emerged and organizational leaders also have an effect on how leadership is manifested.

Several contemporary Muslim organizational leaders are well-educated first generation migrants who have not yet participated fully in Australian life. Data show that these first generation migrants still have a deep level of connection with their ethnicity and with their homelands overseas. Moreover, they think of themselves as more capable to lead AMOs than their counterpart Australian-born Muslims. Most of the recent generation migrant leaders remain reliant on their ethnic constituencies. Organizational culture was found to be completely subsumed within different overseas nationalistic cultures. It was also found to be a sub-factor of ethnic cultures. Representative quotes for the theme role of organizational culture are provided in Table 5.

Table 5. Role of organizational culture: illustrative quotes

a Islamic Council of Victoria.

It became apparent that the resolution of our research problem lay within the area of overlap between the two macro-cultural categories: Australian culture and Islam. The true nature of the complexity in this cultural overlap provided insights into how leadership was enacted in Muslim organizations. Cultural complexity was found to be multi-dimensional. These dimensions of cultural complexity are examined below.

Cultural complexity

Ethnocentric thinking

Ethnocentrism is the belief that one's culture is superior to others (Levine, Reference Levine and Wright2015). It might also be accompanied by a feeling of contempt for those considered foreign. This definition reflected the actions and beliefs of many within the Islamic community.

In Australia, immigrant Muslims resides in homogeneous national groups. Cultural identity is formed through locally-based social ethnic groups. Moreover, it became clear that for Muslims in Australia, cultural or ethnic identity is much stronger than Islamic identity. Immigrant Muslims are articulate about preserving their own social life, traditions, politics and language, and identify with ethnic cultural issues rather than a common Islamic platform. It was clear that Australian Muslims also had a considerable amount of cultural complexity within their fragmented ethnic groups superimposed upon the organizational cultural complexity that was more readily apparent.

One outcome of ethnocentric thinking was to inhibit the work of organizations that claim to represent Muslims in Australia. It was found that the resulting uncertainty led to heightened levels of stress and generated negative emotions within people. Illustrative quotes from Table 6 show that, at a more practical level, the negative outcome is represented by power struggles and an inability to get talented men and women from different groups to participate in advancing the cause of the Australian Islamic organizations.

Table 6. Cultural complexity (ethnocentric thinking): illustrative quotes

Representative quotes for the theme cultural complexity (ethnocentric thinking) are provided in Table 6.

Negligence

Some respondents considered that organizations for Muslims in Australia were ‘negligent’, both of modern organizational systems and with regard to basic Islamic work ethics. Participants identified an uncertainty stemming from the clash between Islamic cultural expectations and Australian cultural and procedural expectations on the one hand, and ethnic cultural expectations on the other hand. There is a lack of integration of Islamic principles of transparency, accountability, equality, piety and justice with Western leadership theories in order to manage Muslim organizations in the modern Australian context. Representative quotes for the theme cultural complexity (negligence) are provided in Table 7.

Table 7. Cultural complexity (negligence): illustrative quotes

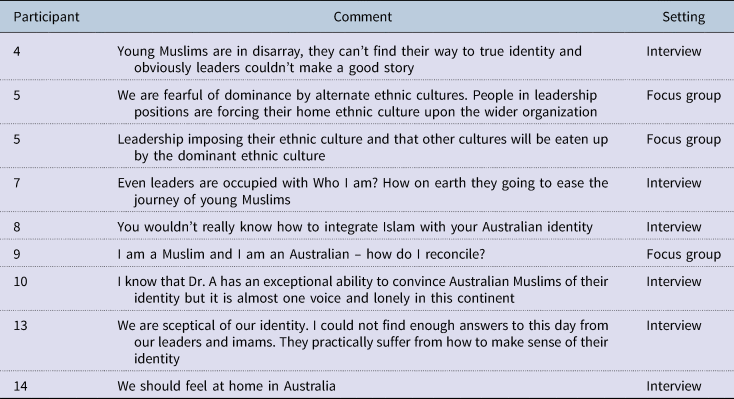

Leadership identity struggle

We found culture and identity to be strongly related, with a strong covariance between identity crisis and culture dominance. It became increasingly obvious as the categories took shape that a problematic outcome of identity crisis and culture dominance revolves around the difficulty Muslims have in finding a leadership identity. Many Australian Muslims, whether as individuals, leaders or members of communities, exemplify the notions of the ‘hoped-for’ and ‘feared’ self (Oyserman & Markus, Reference Oyserman and Markus1990). ‘In 2011, 38% of Muslims in Australia were Australian born and another 39% were born in Lebanon, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Turkey, Bangladesh, Iraq, Iran, Indonesia and India, making them one of the most ethnically and nationally heterogeneous communities in Australia’ (Hassan, Reference Hassan2015: 19). This heterogeneity suggests that different cultures have very different expectations about behavior and identity (Markus & Kitayama, Reference Markus and Kitayama1991).

As Faris and Parry (Reference Faris and Parry2011) have argued, Muslim leaders in Western countries might fear the expectations of others around them. In the Australian context, an individual's leadership style may be a confusing and complex combination of ethnic, Islamic and Australian macro-culture leadership styles. While many Muslims in Australia struggle with identity, there is a lack of guidance from Muslim leaders in bridging this identity rift leadership. Participants’ comments suggest that cultural and identity struggles may have a negative impact on very basic tenants of leading. When leaders lose that sense of strong identity and belonging they may lack impact. On the other hand, Parry (Reference Parry1999) and Kan and Parry (Reference Kan and Parry2004) have found that the resolution of paradox and uncertainty is the essence of leadership.

Toward the later stages of the research, and at a higher level of abstraction, it became clear that Muslims and their leaders were engaged in a larger-scale identity search to resolve what it means to be a Muslim in contemporary Australia, rather than what it means to be a Muslim leader. This identity challenge is one outcome of the complex cross-cultural context faced by Australian Muslims.

Representative quotes for the theme cultural complexity (leadership identity struggle) are provided in Table 8.

Table 8. Cultural complexity (leadership identity struggle): illustrative quotes

Discussion

The iron cage of organizational cultural complexity

With ongoing analysis we soon found that our categories were saturated. No new or innovative insights were forthcoming. We were able to discover little that was unique about how leadership was operationalized in this substantive setting. However, it was clear that the issue at stake was the negative impact upon leadership that came as a result of the interaction of the three cultural settings: Australian macro-culture, Islam and ethnic cultures. The difficulties generated by the intersection of these three cultural settings were very problematic for the effective performance of leadership. Perhaps it is the internal complexity of the ethnic cultures in Australia that makes this context problematic. However, leadership within an organizational culture added a further dimension of cultural complexity. The categories that emerged were all manifested most strongly when the three layers of culture came together.

We call this interaction effect the ‘iron cage’ of cultural complexity (see Figure 1). Here, we use the iron cage as a metaphor for the behavioral control of leaders and followers that is exerted by the complex cultural context in which Islamic organizations operate in contemporary Australia. This notion resonates with Sackmann's (Reference Sackmann1997: 2) explanation that cultural complexity encompasses the simultaneous existence of multiple cultures that may contribute to a homogeneous, differentiated and/or fragmented cultural context.

Figure 1. Cultural complexity

Total institutions

Weber (Reference Weber1958) referred to the iron cage as a metaphor for the constraining and controlling effects of bureaucracy. We posit that the many sub-cultures located at the intersection of this cultural complexity represent a form of total institution that constrains leadership.

Goffman (Reference Goffman1961) coined the term total institutions to refer to those organizations that control almost the totality of the individual member's day-to-day life. The term originally and usually refers to an enclosed, formally-administered life, typified by institutions like mental asylums and prisons. In total institutions there is little opportunity for choice and no possibility of meaningful escape (Grey, Reference Grey2009). However, Clegg, Kornberger, and Pitsis (Reference Clegg, Kornberger and Pitsis2008) suggested that membership of total institutions can be voluntary in nature. Scott (Reference Scott2010) used the term ‘reinventive institutions’ to describe places where people retreat voluntarily for rehabilitation and self-reflection. Examples of reinventive institutions include monasteries, rehabilitation clinics and boarding schools. Scott cited the example of the ‘Big Brother’ house. The notion of voluntary admission suggests that the total institutional concept can be applied without the incarceration originally assumed necessary. Therefore, Burrell (Reference Burrell1988) suggested, and Clegg (Reference Clegg2006) agreed, that the characteristics of the total institution can be applied to normal organizational forms.

Incorporating the notion of the voluntary organization or the normal organization within the scope of the total institution, Clegg (Reference Clegg2006) suggested that obedience is a more fundamental question than resistance. A strong form of socializing takes place in total institutions. Individuals cannot escape the complexity, confusion, the sense that there is no future. Therefore, individuals try to be good ‘inmates’ or members of the institution. In the Australian Muslim context, the different sub-cultures streamline individuals’ identities, hopes, aspirations, belonging and sense of self. The sense of in-group self stems from the privileged ethnic for-granted self (Goffman, Reference Goffman1961). Ethnic identity construction aligns smoothly with the daily life and interaction with one's own group and ethnic entity. The behaviors and attitudes toward others spell out the reality of total institution.

Total institutions are, by definition, closed off from the wider society (Clegg, Reference Clegg2006). Organizational members will have difficulty in maintaining an identity as part of the larger society if they feel like a member of a total institution. Therefore, as Clegg suggested and we claim, there is a bit of every ‘normal’ organization to be found within the total institution, and there is a bit of the total institution to be found within every ‘normal’ organization. This seems to be true for 40 hr per week, at least.

Hence, because this research is not dealing with formally-constructed total institutions, we suggest that the total institution reflected in the iron cage of cultural complexity is socially constructed. People are not physically constrained. However, they feel this level of social constraint, possibly as strongly as in any ‘conventional’ total institution. Participants’ comments showed that people are implicitly constrained to favor their peers from the same national, ethnic and cultural background in terms of socialization, promotion and organizational and community work, whether this work is voluntary or paid. Australian Muslims to a large extent live in a free democracy but they chain themselves with assumptions and presumptions about their fellow Muslims and Australians in general. Their behaviors and attitudes are not confined to personal interactions but transcend to the organization and community. Whether intentional or not, this cements the barriers around each group and separates them from other groups; this is the case for total institution where individuals, ‘cut off from the wider society … together lead an enclosed, formally administered round of life’ (Goffman, Reference Goffman1961: xiii).

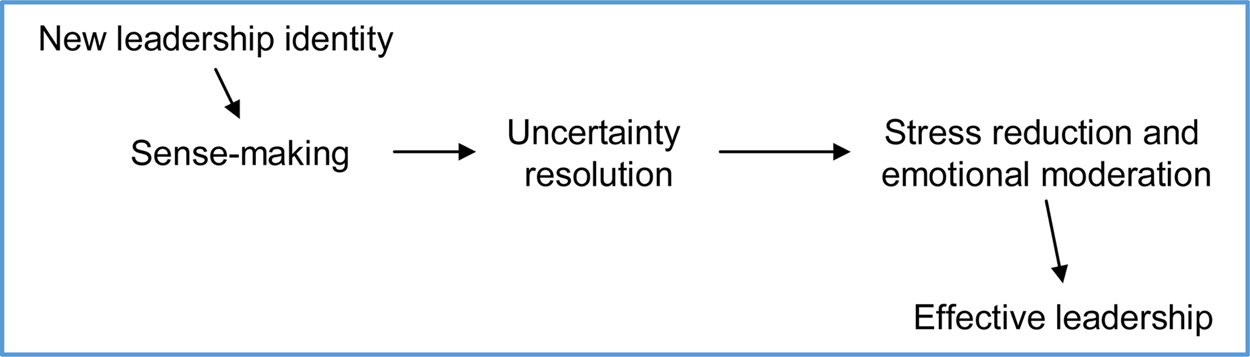

Breaking free from the iron cage of cultural complexity might involve changing the social construction of the reality that people endure as a result of their lived experience. We propose that there is a role here for the generation of a new leadership identity within these organizations. This leadership will assist with the sense-making of all organizational members about the nature of their existence within this complex context. This sense-making will in turn reduce stress and generate more positive affect, leading to better leadership outcomes.

Responses to Research Question

The research question asked how leadership operates across cultures within this substantive setting. The short answer is that leadership is problematic within this setting. Indeed, leadership is the victim of the iron cage of cultural complexity. This problematic result from the complexity of multiple cultures operating concurrently makes it difficult for a leadership identity to develop among the organizational members. This cultural complexity is perhaps unique to the context of Australian Muslims.

Leadership Response to Cultural Complexity

Leadership challenge: accommodating cultural complexity

Clearly, any potential resolutions to this leadership challenge are complex. However, this research suggests some opportunities for removing people from the metaphorical and socially-constructed ‘iron cage’. First, we suggest that effective leadership will come from stress reduction and emotional moderation. Individuals will be able to demonstrate leadership when stress is reduced and emotions – in particular negative emotions – are felt less strongly.

Cultural complexity is confusing and therefore stressful for members. As other researchers have found, uncertainty resolution (Parry, Reference Parry1999) and sense-making (Pye, Reference Pye2005) will reduce stress and moderate emotions. In addition, we propose that a new leadership identity for members of the organization will enhance sense-making. The management of cultural complexity can be represented as an abstract storyline that all members of the organization can become a part of. See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Story-line: toward effective leadership

It is not within the purview of this research to propose solutions to problems. However, we need to expand upon the notion of the ‘new leadership identity’. Ely, Ibarra, and Kolb (Reference Ely, Ibarra and Kolb2011) conceptualized leadership development as identity work. Similarly, we are suggesting that a new or enhanced leadership identity will lead to more effective leadership in practice. This outcome is achieved via the intervening variables of sense-making, uncertainty resolution and emotional moderation, for people in leadership positions as well as for other members of the organization.

Faris and Parry (Reference Faris and Parry2011) provided some suggestions for improving leadership outcomes. However, we propose some general suggestions that have resulted from this research. Any suggestions should ultimately have the aim of ameliorating the dimensions of cultural complexity that emerged from this research. They should revolve around blurring the boundaries of cultural complexity and, in so doing, generate a more efficacious leadership identity for Muslims. It should also reduce stress and extreme emotions for non-Muslims also working in these organizations. The long-term vision of an Australian Islamic identity could bring change across the work spectrum for Muslims in Australia. Any such vision will have to be at once grounded in the roots of Muslim identity and positively engaged with the broader Australian society. At the same time, Muslim leaders must concentrate on the authentic substance of Islamic values including humility, unity, equality, piety and justice, while avoiding antagonism and rhetoric.

Leadership to embrace other cultures – inclusion, not exclusion

A recent example of embracing other cultures with the aim of inclusion involves the organization Islamic educational and learning sessions for secondary schools through mosques and Islamic centers. The researchers attended several sessions and observed a healthy discussion between students and Imams from the Australian Muslim community. During these sessions, students were able to discuss issues of importance to them in an open way. Some of these students heard about Islam and Muslims from Muslim leaders and Imams for the first time in their life. This exchange of visits and discussions is an obvious sign of work toward inclusion. The students are hearing from integrative Islamic role models, rather than from the disintegrating complexity of various national Islamic role models.

The theme of respect is inherent within this issue. The suggestion is that respect will overcome ethnic differences and generate a more inclusive society. In Australia, sporting role models are respected and include Hazim el Masri (Rugby League) and Usman Khawaja (Cricket). These sportspeople are respected by all Australians. Perhaps they are archetypes for the cultural inclusion that will help to generate a new identity for Muslim Australians. In the same way, they are role models for non-Muslim Australians. Perhaps Muslims and non-Muslims must together engage in the learning and sense-making that is needed to generate the required inclusivity.

Practical Implications and Policy Recommendations

There are several practical implications that can be drawn from this research. The focal contribution relates to the accommodation of cultural complexity in AMOs within a context of new ways of leading. AMOs need to understand that culture is central in terms of socioeconomic, management, leadership and organizational work. For Australian Muslims, accommodating cultural complexity could ultimately lead to different consequences and outcomes.

For instance, the socioeconomic position of Australian Muslims is very weak, which may lead to real or perceived disempowerment (Hassan, Reference Hassan2010). Australian Muslims have significantly higher unemployment rates compared with non-Muslim Australians. This economic disadvantage creates barriers to achieving aspirational, social and cultural goals, thus impeding the social inclusion of Australian Muslims and cohesion in Australian society (Hassan, Reference Hassan2010: 584). Research suggests that culture is an important predictor of unemployment (Brügger, Lalive, & Zweimüller, Reference Brügger, Lalive and Zweimüller2009). Reducing unemployment is vital for reducing Australian Muslims’ disadvantage and a factor in enhancing economic performance. Developing strong and effective organizational cultures through accommodating cultural complexity may lead to improved economic outcomes. Research shows that certain organizational cultures correlate positively with economic performance that transcend into organizational strength and improvement (Sorensen, Reference Sorensen2002; Boyne, Reference Boyne2003).

Furthermore, organizational cultures emerge from the dynamic interaction of followers’ choices and leaders decisions (Klein, Wallis, & Cooke, Reference Klein, Wallis and Cooke2013). Followers’ choices include promoting future leaders and managers, and leaders’ decisions include hiring the right personnel (Schein, Reference Schein2010). Leader decisions and follower choices are part of their behaviors and actions which relate to culture and identity (Epitropaki, Kark, Mainemelis, & Lord, Reference Epitropaki, Kark, Mainemelis and Lord2017). Given that macro-culture and identity are multifaceted and inter-related (Leff, Reference Leff, Morgan and Bhurga2010), it could be expected that these intertwined constructs are important for shaping organizational culture and leadership.

This study also highlighted that accommodating cultural complexity and embracing other cultures are effective leadership strategies for softening the negative impacts of cultural complexity. Leaders should, therefore, focus on developing these leadership strategies in multicultural contexts. They should foster and build healthy relationships based on respect and service to members of the organization regardless of their background, ethnicity or profession. In addition, Muslim leaders should seek to develop a healthy mix of the Australian and Islamic culture that emphasizes pluralistic culture and avoids ethnocentrism that can cripple the organizational culture. There is a need to develop a more cohesive organizational culture through cultural awareness initiatives that incorporate a healthy emphasis bringing people together rather than separating them.

Federal and state governments, in collaboration with intellectual leaders, successful Muslim figures and Imams could develop workshops to enhance the understanding, perceptions and capabilities of working through seemingly contradictory cultural world-views and identities. Policy-makers should think seriously about assisting AMOs with repertoires of leadership competencies in order to diagnose, change and lead organizational cultures. The importance of understanding, harnessing and leading such effort cannot be underestimated in terms of creating an environment for change and further achieving the intended outcomes. These endeavors would necessarily require strong governmental support.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our analysis identifies tensions between macro- and micro-cultures in the context of Australian Islamic organizations. The interplay of cultures and sub-cultures impacts the lives of individuals, organizations and communities. Solutions for this challenge are complex and difficult, but the issue needs to be addressed. Although this research focused specifically on the context of AMOs, the research is of relevance to other multicultural contexts. In terms of the future of cultural-leadership research, this investigation has shown gaps in our knowledge and thereby serves as a call for more conceptual and empirical work in this important area.

Author ORCIDs

Nezar Faris, 0000-0002-5391-5058.

Acknowledgment

Ken Parry passed away peacefully on 11 February 2018. He was the inspiration for this piece of work. This article is a dedication to his memory.

Appendix