In anticipation of Nigerian independence in October 1960, Northern Nigerian political leaders, officials from the Ministry of Trade and Industry and the Northern Region Development Corporation as well as local businessmen sought to replace imported manufactured textiles – mainly from the UK – with Nigerian-made cloth. By partnering with foreign textile-manufacturing firms that could provide textile technology and expertise, they hoped to produce locally manufactured cloth for the Nigerian market. In April 1955, the premier of the Northern Regional Government, Ahmadu Bello, along with Northern Nigerian government officials, met with managers of the British textile firm David Whitehead & Sons (Maiwada and Renne Reference Maiwada and Renne2013: 174). Together, they successfully negotiated arrangements to build Kaduna Textiles Limited (KTL), the first large textile-manufacturing mill in Kaduna, Northern Nigeria, which began production in 1957. In the following decade, arrangements were negotiated for the establishment of several other textile mills in Kaduna – which included Nortex, Arewa Textiles and United Nigerian Textiles Limited (UNTL), among others.

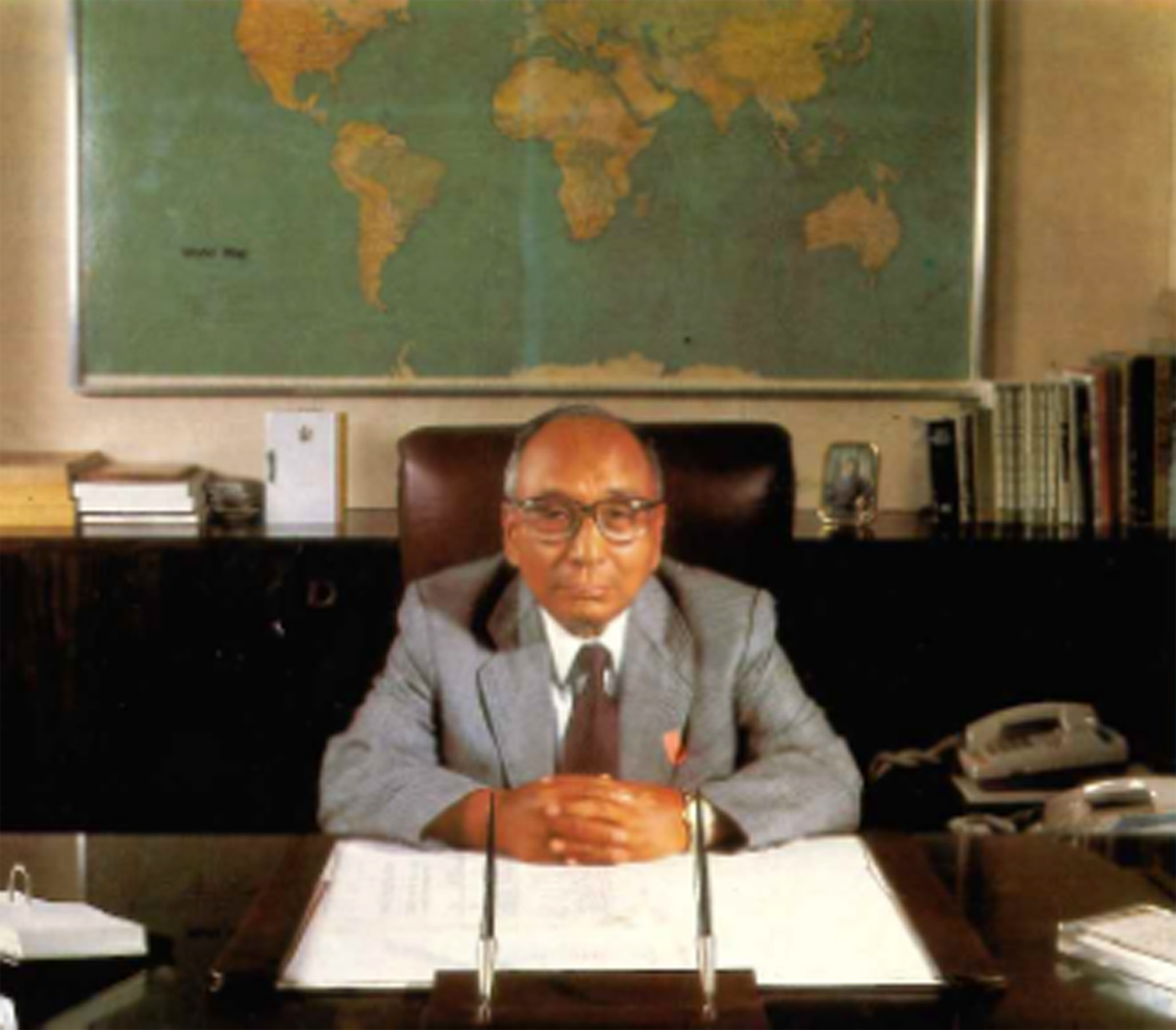

The opening of the UNTL mill in Kaduna in 1964 represented the first business collaboration between a Chinese textile manufacturer and the Northern Nigerian Regional Development Corporation (Andrae and Beckman Reference Andrae and Beckman1999). This mill – the largest in Northern Nigeria – was the first overseas operation for the newly established Hong Kong-based Cha Group, headed by Cha Chi Ming (Figure 1).Footnote 1 In the following years, the Cha Group established several other mills in Nigeria, including one of the largest textile mills in Nigeria, Nichemtex Industries Ltd (in Ikorodu-Lagos in 1971), and the vertically integrated textile mill Funtua Textiles Ltd (in Funtua, Katsina State, in 1978). Both Chinese and Nigerian managers and workers were engaged at these mills, which by 1980 provided plain and printed cotton textiles to the Nigerian market as well as to markets elsewhere in West Africa (Axelsson Reference Axelsson2012: 41). While the Funtua mill has since ceased operation, the UNTL (Kaduna) and Nichemtex (Ikorodu-Lagos) mills merged in 2001 to form the company United Nigerian Textiles Plc. These two large mills have continued to manufacture textiles, although after UNT Plc was delisted from the Nigerian Stock Exchange in August 2011 (Eboh Reference Eboh2011), its administrative staff moved to the company's Marina Street offices in Lagos. Nonetheless, the Cha Group has maintained its commitment to textile manufacturing in Nigeria through its Kaduna and Lagos UNT Plc mills.

Figure 1 Mr Cha Chi Ming in a photograph included in the 1989 UNTL annual report.

Cha Chi Ming, who was born in Haining City, Zhejiang Province, left mainland China after the Communist Revolution in 1949, joining those opposed to the socialist state and its control of private business. His success with the founding and growth of China Dyeing Works Ltd, a small textile-dyeing factory in Hong Kong, formed the basis of the Cha Group, which has since become a major international conglomerate based in Hong Kong and the UK. Cha Chi Ming's position as a private citizen and member of the Hong Kong business elite distinguished him from government officials of the People's Republic of China who sought to support industrial development in socialist African states such as newly independent Tanzania. Thus, the Tanzania–China Friendship Textile Company Ltd (URAFIKI) mill in Dar es Salaam was built with Chinese financial and technical assistance and began production in 1968 (Brautigam Reference Brautigam2009; Xiaoyang Reference Xiaoyang2014). Yet while Cha Chi Ming may not have approved of Mao's government and used private capital to establish the UNTL mill in Kaduna, he nonetheless shared a sense of social idealism. He was convinced that Cha Group's management skills could both improve Nigerian workers’ knowledge of industrial textile production and support beneficial labour relations. For him, good business practice was also a social good (Andrae and Beckman Reference Andrae and Beckman1999: 113–14).

Subsequent events in China have blurred this distinction between government- and privately-funded textile-manufacturing ventures, as well as between national identities associated with the People's Republic of China and Hong Kong. In December 1984, an agreement was signed by UK and Chinese officials which led to the incorporation of Hong Kong as the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China in 1997 (Leung Reference Leung2018). In addition, the successful establishment of four special economic zones (SEZs) in south-eastern China in 1979 (Brautigam et al. Reference Brautigam, Farole and Xiaoyang2010: 3), which fostered foreign investment in a range of industries, led to the expansion of industrial zones for private textile manufacturing in several Chinese cities, including those in Zhejiang Province. Not surprisingly, the Cha Group has since set up three textile mills in Zhejiang Province,Footnote 2 two of which are located in Haining City, Cha Chi Ming's birthplace. The government's shift towards promoting private business initiatives in China may also be seen in subsequent textile-manufacturing interventions in sub-Saharan Africa, where private Chinese textile firms have entered into business arrangements with African mills. For example, in 1995, Zhu Rongji, then the Vice Prime Minister of China, assigned a private Chinese partner, the Changzhou Textile Group, which received a US$100,000 loan from the Export-Import Bank of China (Xiaoyang Reference Xiaoyang2014: 121–2), to renovate and manage the Tanzania–China Friendship Textile Company Ltd (URAFIKI). Such arrangements may be seen in other more recent Chinese projects in Africa associated with the Chinese Belt and Road initiative announced by President Xi Jinping in 2013 (Salau Reference Salau2017).

The viability of the continued collaboration between the Cha Group and Northern Nigerian government officials in the operation of the UNTL mill in Kaduna as well as subsequent textile-manufacturing interventions associated with the Chinese Belt and Road initiative surely reflected the particular political and economic situation in African countries such as Nigeria (Brautigam Reference Brautigam2009: 21). Yet, as has been the case in the past, changes concerning textile manufacturing within the People's Republic of China and the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region are likely to have an impact on textile production in Africa.

This article examines these changing but continuing African–Chinese textile-manufacturing collaborations by focusing on an early example from Northern Nigeria. Specifically, it considers the relationships between the Nigerian government and a Chinese multinational corporation – the Cha Group; between the UNTL mill managers and Nigerian government officials; and between Chinese and Nigerian textile workers. It begins with a discussion of the company's history in Kaduna and the business model of the company's chairman, Cha Chi Ming, which is based on twenty years of published UNTL annual reports, Nigerian archival documents, Ahmadu Bello University files, government reports and secondary literature (particularly Andrae and Beckman Reference Andrae and Beckman1999). The article then considers two aspects of UNTL production in Kaduna, namely UNTL managers’ attempts to access raw cotton grown in Nigeria and relations between UNTL management and Nigerian workers. Despite the company's efforts at encouraging local cotton production and its support for workers’ training and union demands, the UNTL mill in Kaduna (along with its affiliated mills in Funtua and Gusau) closed in 2007. Yet the subsequent reopening of the UNTL Kaduna mill with a loan from the Nigerian government's 100 billion naira Cotton, Textile and Garment Development Fund in 2010 has been affected by the upsurge in textile manufacturing in China and Chinese textile exports since the mid-1980s. The article concludes with a discussion of aspects of the possibilities and constraints facing African–Chinese textile-manufacturing collaboration in Northern Nigeria.

UNTL: a Chinese–Nigerian textile-manufacturing collaboration

Chinese–Nigerian textile-manufacturing collaboration began in 1962, when Cha Chi Ming, chairman of the Cha Group, and members of the Northern Nigerian Development Corporation met in Kaduna. The UNTL mill, which opened in 1964, grew out of this collaboration (Figure 2). The initial growth of UNTL and the economic benefits of Nigerian investments led to further collaboration. UNTL officials later acquired the spinning company Norspin (which was renamed Unitex Ltd) in 1980 and the Supertex Ltd mill with printing facilities in 1983, both in Kaduna. By acquiring Norspin, the Cha Group used a strategy of backward integration in order to avoid the expense of imported yarn and also to take advantage of the local production of cotton. However, as the number of textile-manufacturing mills grew, local cotton producers could not supply sufficient raw cotton for textile production needs in the country. A cotton-growing and marketing company, the Nigerian Cotton Company Ltd, which was organized by the Nigerian Textile Manufacturers’ Association in 1986 and which the Cha Group supported, was not successful (Andrae and Beckman Reference Andrae and Beckman1987: 52–3). Nonetheless, the Cha Group was able to draw on multinational companies for cotton, yarn and dyeing supplies (Andrae and Beckman Reference Andrae and Beckman1999: 109–10). During this period of growth for the textile industry, which reflected the larger Nigerian economy – namely the ‘oil boom’ years of the 1970s – there was an increased demand for manufactured textiles. Other Nigerian textile mills without such international connections were unable to access sufficient imported cotton, thread and dyes.

Figure 2 Photograph taken of textile mill worker at the UNTL Kaduna plant, 26 February 1971, by the Czech photographer Francis Uher. Courtesy of the Ministry of Information, Kaduna.

Following the drop in oil prices in the early 1980s and the accumulation of an enormous foreign debt, the naira was devalued as part of the implementation of a structural adjustment programme in 1985. Unlike other textile manufacturers in Kaduna, which relied on laying off workers and shutting down mills, UNTL management used various measures to reduce its workforce, mainly by a method of ‘natural wastage’ based on retirement and dismissals reflecting stricter workplace discipline, although at times work hours were limited (Andrae and Beckman Reference Andrae and Beckman1999). However, long-service awards were also implemented to retain older, experienced workers. These aspects of worker–management relations, which were supported by the Cha Group, contributed to good working interactions between Nigerian and Chinese mill officials and workers. In addition, Chinese workers’ active participation in the everyday functioning of UNTL generated a sense of mutual concern in the company's success among workers. UNTL also changed production and marketing strategies to adapt to structural adjustment and the decline in consumers’ purchasing power. In the mid-1980s, it developed a line of higher-quality textile prints that were attractive to Nigerian consumers as well as to foreign buyers. By 1990, it was reported to be exporting up to 25 per cent of its products.

Cha Group chairman Cha Chi Ming also made a point of contributing to the education of workers, both by sending them for overseas training and by working with local universities, polytechnics and colleges for student training. According to materials amassed to support his nomination for an honorary degree, Cha Chi Ming was respected for his contributions to the textile industry, health delivery system and education in Nigeria. Aside from establishing UNT Plc textile mills in Kaduna, Zamfara and Lagos, he also introduced modern textile technology for weaving, spinning, dyeing and pollution control, installing the UNT Plc's ‘own Effluent Treatment Plant to ensure an effective protection of the environment’.Footnote 3 In addition, he awarded ‘postgraduate scholarships, training employment, reagents and fluid cash to institutions of higher learning’ such as Ahmadu Bello University and Kaduna Polytechnic.Footnote 4 At Kaduna Polytechnic, UNTL also participated in the Student Industrial Work Experience Scheme, which provided training to 160 students annually. In recognition of his contribution to Nigerian educational institutions and to the development of the textile industry in Northern Nigeria, Cha Chi Ming was awarded an honorary doctorate (DSc honoris causa) from Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, in 2006.

The UNTL business model

Cha Chi Ming's business model for the UNT Plc textile mills was based on his successful management of China Dyeing Works Ltd in Hong Kong. His business strategies for manufactured textile production in Nigeria focused on three factors: (1) his astute application of innovations in textile manufacture as well as flexibility in textile production and marketing; (2) his understanding that post-independence Africa was poised for local textile manufacture with new governments eager to support such interventions; and (3) his conviction that Cha Group textile mill management should improve Nigerian workers’ knowledge and maintain good labour relations, as well as provide other culturally relevant work incentives. This model, with some adjustments over the years, was quite successful – despite recurrent obstacles to the success of textile manufacturing in Nigeria (Taylor Reference Taylor2007). However, this business model for Chinese–Nigerian collaboration in textile manufacturing could not overcome factors external to the industry, such as a declining infrastructure, particularly electricity, and frequent changes in political leadership at the federal level. Also, Andrae and Beckman (Reference Andrae and Beckman1999: 34) note that the ‘smuggling [of textiles from the UK and the Netherlands] was rampant during the oil boom years due to the increased value of the naira’, while the subsequent decline in value led to the smuggling of less costly imported textiles – often from China, as Cha Chi Ming pointed out in his chairman's annual statement for 1987 – which undermined local textile manufacturing (Akinrinade and Ogen Reference Akinrinade and Ogen2008). In addition, the inflationary pressures associated with the national oil industry undermined agricultural production, specifically Nigerian cotton production.

In UNT Plc's 2007 annual report and accounts,Footnote 5 the Kaduna mill's closure in October of that year was attributed to the many problems facing the industry. The acting director of UNT Plc, Muhammadu Dikko Yusufu, noted that:

The future of the textile industry is in very serious doubt. The Government must finally take effective measures and also urgently take decisive action that would help the industry to survive. Some of these measures must include combating smuggling, fighting against counterfeits to protect Nigerian brands, restoration of the power sector as well as substantial improvement in other infra-structural facilities.

The Nigerian government initially did attempt to resuscitate the textile industry, beginning in late 2007, when the former President Obasanjo initiated the 70 billion naira Textile Revival Fund (Ahmed Reference Ahmed2008). This fund was expanded and renamed in 2009. The 100 billion naira Cotton, Textile and Garment Development Fund (CTGDF) was then organized through a bond issued by the Debt Management Office. The Bank of Industry distributed CTGDF loans to three companies in Kaduna State: Zaria Industries Ltd-Zaria, UNTL-Kaduna and Chellco Industry-Kaduna (Agbese et al. Reference Agbese, Alabi, Ahmadu-Suka and Iloani2016). On 3 December 2010, Vice President Namadi Sambo officiated over the reopening of UNT Plc-Kaduna (Mudashir and Alabi Reference Mudashir and Alabi2011; Williams Reference Williams2011a). Since reopening, UNT Plc-Kaduna's production has focused on cotton thread and cotton baft (grey cloth), manufactured with newly purchased computerized looms, made possible with a CTGDF loan.

This situation also led the Cha Group to make major changes in its textile-manufacturing practices in Nigeria in the twenty-first century. As the company has continued production in some mills and has amalgamated its operations, it has also developed a new business model for some of its marketing operations in the country. While the UNTL mill in Kaduna could not economically produce quality printed textiles under the infrastructural constraints and increasing competition with Chinese textile imports, the mill at Ikorodu-Lagos has continued to produce cotton print textiles under the UNT Plc brand names of Classic Wax, Diamond Wax, Rainbow Wax, UNTL Wax and Nichemwax. However, with their knowledge of the Nigerian textile market, Cha Group officials used their experience in Nigeria as the basis for a new business model: namely, the marketing of branded high-quality manufactured textiles, known as Da Viva®, at company franchise shops in major Nigerian cities (Abah Reference Abah2011; Renne Reference Renne, Gott, Loughran, Quick and Rabine2017). More than nine shops selling the Da Viva® line of printed cotton textiles have opened in Lagos, with another four in Ibadan, three in Abuja, and one in Kaduna (Figure 3) (Renne Reference Renne, Gott, Loughran, Quick and Rabine2017).Footnote 6 Referred to as ‘modern’ ankara (Yoruba) or atamfa (Hausa) wax prints in the Nigerian press, these textiles update earlier wax print designs. UK-based designers associated with the A. Brunnschweiler & Company Ltd (ABC), which the Cha Group acquired in 1992 (Axelsson Reference Axelsson2012: 41, note 24), use digital designing to depict freer pattern forms in new colour arrangements. These patterns are transferred electronically to the Cha Group textile mill, Akosombo Textiles Ltd, in Akosombo, Ghana, for producing Da Viva® cotton print textiles (Elanda Reference Elanda, Gott, Loughran, Quick and Rabine2017: 66; Miescher Reference Miescher, Gott, Loughran, Quick and Rabine2017: 88).Footnote 7 The Cha Group also took advantage of digital innovations, not only in the printing of these popular textiles,Footnote 8 but also in their marketing on an attractive new website. These Da Viva® brand textiles also have their own unique trademark and names (Elanda Reference Elanda, Gott, Loughran, Quick and Rabine2017: 66).

Figure 3 Da Viva® store manager, wearing a shirt made with Da Viva® cotton textile print material, with shelves of yardage for sale behind him, in Cocoa Mall, Dugbe, Ibadan, 13 June 2015.

UNTL annual reports: some major themes

The chairman's statements in the UNTL/UNT Plc annual reports were written by Cha Chi Ming until his death on 28 March 2007 (Figure 4). These statements provide a detailed picture of the various aspects of the Kaduna UNTL mill (and its affiliates), including company accomplishments and setbacks; the integration of cotton buying and ginneries within mill premises; worker benefits (training, subsidies, housing and medical treatment); retirement plans to retain workers; and background details of the previous year. The following discussion focuses on two aspects of these reports: (1) the procurement of cotton and its impact on textile manufacturing; and (2) the implications of worker benefits for management–worker relations.

Figure 4 Cover design of UNTL's annual report and accounts for 1989.

Cotton production, ginneries and spinning

The company's difficulties in obtaining raw cotton were noted by Cha Chi Ming in the 1974 chairman's statement:

At the beginning of 1974, the textile industry in general was still in recession due to the previous year's drought in the Northern States which adversely affected the economy of the whole area. Manufacturers faced poor market demand coupled with inflation in prices of raw materials and a severe shortage in supplies of local raw cotton. The Government showed appreciation of the manufacturers’ difficulties by permitting them to import raw cotton supplies free of import duty to make up for the shortfall in local supplies.

He also described how this problem of accessing cotton was addressed:

Shortage of raw materials continued to be a problem, due to increasing port congestion at Lagos, and imported cotton supplies were held up for some considerable time. We overcame this by purchasing cotton from Dahomey [Benin] and Chad and transporting it by road to our factory, thus enabling normal production to be maintained.Footnote 9

The problem of raw cotton availability was also compounded by inflation (associated with the oil boom years), which meant that the prices paid for Nigerian raw cotton put Nigerian-manufactured textiles in an uncompetitive position:

The present price of locally-produced raw cotton, 44 kobo per lb. is higher than the world market price and the Nigerian Produce Marketing Company has announced that the final 5% of last season's cotton crop will be sold to manufacturers at 56 kobo per lb., which is 70% higher than the current world market price on a c.i.f. basis.Footnote 10

It is possible that this price increase had a beneficial effect on cotton production: the amount of cotton sold in 1974 increased 69 per cent from the previous year. Cotton production increased until 1978, when government fiscal and monetary efforts to curb inflation reduced business activities and demand for raw cotton. According to Cha Chi Ming's statement in the 1980 annual report, ‘insufficient supply of local raw cotton’ was a major problem for UNTL mills:

The shortfall was about 63,800 bales which had to be imported. The total requirements for raw cotton as submitted to the Nigerian Cotton Board by the millers were 330,500 bales but the Nigerian Cotton Board had only 266,700 bales. What was even more frustrating was the delay in deciding on who should import cotton as between the millers and the Nigerian Cotton Board. This delay had the effect of slowing down our procurement overseas and in the meantime world prices of cotton had risen considerably.Footnote 11

In addition, textile manufacturers had increasingly imported cotton thread, contributing to cotton production decline until the mid-1980s, when major changes in the government's involvement in cotton production and marketing took place. Since it was one of the largest consumers of Nigerian raw cotton, UNTL took part in these discussions.

As imports of raw cotton and cotton thread became untenable with the devaluation of the naira in 1985, some companies sought to establish cotton plantations that would guarantee sufficient cotton for their mills.Footnote 12 Officials at UNTL argued for an expanded model of the one used by the Nigerian tobacco industry:

The NTC [Nigerian Tobacco Company] model was taken up and elaborated by the United Nigerian Textiles Ltd., UNTL … in a concrete proposal backed by a consultancy report presented in March 1985. The main suggestion was for the formation of a company, where all textile mills would be required to purchase shares. Ginners, (seed crushing) oil mills and also the Cotton Board would be asked to join … The new company would operate by a hierarchically organised input distribution and marketing organisation with spraying, tractor hiring, and demonstration services to offer … The base of the hierarchical organisation would be groups of farmers led by ‘contract farmers’ of which 4–5 would connect with one of some 400 extension agents from the organisation. (Andrae and Beckman Reference Andrae and Beckman1987: 45)

When this proposal was not accepted by the Nigerian Textile Manufacturers’ Association, UNTL management opted for ‘separate buying arrangements’ (Andrae and Beckman Reference Andrae and Beckman1987: 53). In his 1986 chairman's statement, Cha Chi Ming noted:

In an effort to minimize the problem of scarcity of the most essential raw material, your company has mounted a vigorous campaign to boost cotton production in the country. In conjunction with all our subsidiaries, we took the initiative to mobilize farmers in the cotton growing states, and particularly in Kaduna, Sokoto, Bauchi and Gongola states by rendering various forms of assistance.

Sani Ismaila, a manager at UNTL in 1987, explained that ‘their deals with local chief farmers and other “contractors”, mostly former Licensed Buying Agents for the Cotton [Marketing] Board’, enabled the company to access local raw cotton (Andrae and Beckman Reference Andrae and Beckman1987: 53). Additionally, in 1986, UNTL officials decided to encourage cotton production by installing ginneries in two of their Northern Nigerian mills; this was reported by Cha Chi Ming in his chairman's statement in the 1987 annual report:

As part of our continuing effort to backward integrate our operations and assist the national economic development efforts, we have already installed ginning machines in two of our subsidiary companies, namely, Funtua Textiles Limited and Zamfara Textile Industries Limited, situated in some large cotton growing areas in Katsina and Sokoto States.Footnote 13 We hope this gesture will stimulate cotton production and give farmers greater encouragement and confidence by reassuring them of good cotton seeds for planting.

In the same annual report, he noted that: ‘Funtua Textiles Limited, Zamfara Textile Industries Limited, and Unitex Limited, performed better than in the previous year due mainly to the fact that more cotton was harvested in the country during the year which has in turn enabled these subsidiaries to increase their production.’ UNTL also realized a profit in 1987, despite an unprecedented rise in the price of cotton.

Worker–management and Nigerian–Chinese relations

Aside from attempting to increase Nigerian cotton production, Cha Chi Ming underscored the importance of maintaining good relations with Nigerian mill staff and workers through his support for a Nigerianization programme. This programme, associated with the Nigerian Enterprises Promotion Decrees of 1972 and 1977 (Andrae and Beckman Reference Andrae and Beckman1999: 34), promoted the integration of Nigerian shareholders and managers, along with a reduction of expatriate staff, and was adhered to at UNTL mills. While several textile mills in Kaduna supported overseas training of Nigerian workers as part of their development agenda, UNTL management facilitated both workers’ training and the growth of local university textile departments. Thus, in his 1974 chairman's report, Cha Chi Ming wrote:

The Company continued to sponsor 156 employees on training courses both in Nigeria and overseas, as well as providing increased in-service-training facilities, and as a result our Nigerianisation programme is progressing steadily. Every effort is still being made to recruit qualified Nigerian staff from all known sources in Nigeria and overseas. Five senior Nigerian staff have been promoted to managerial status and twenty Nigerian employees were promoted to supervisory grade staff in both the technical and administrative sections. Steps are now being taken to assign Nigerian supervisors to supervise completely the production of one shift in furtherance of the implementation of the Nigerianisation programme.

In the following year, Cha Chi Ming observed that the number of UNTL employees had grown from 4,775 to 5,474 by the end of 1975, with ‘the expatriate quota … gradually reduced in spite of ambitious expansion projects envisaged and carried out’. He also noted that, from 1972, they had ‘been able to recruit graduates from Polytechnic [sic], Colleges and Universities to help create a solid foundation of highly educated personnel both in the technical and administrative fields … In 1975, the company recruited 16 graduates from institutes of higher learning and sponsored 144 employees for training courses both in Nigeria and overseas.’

This particular year, 1975, was one of the most profitable for UNTL, according to Cha Chi Ming's chairman's statement:

I am pleased to announce that your company, including its subsidiary, has been very profitable in 1975 … The company's increased profit was the result of a continuous increase in production capacity over the previous years, an increase in the productivity of our employees and increased management efficiency, as well as strict control of manufacturing costs and general expenses, and a reasonable increase in the average selling price in line with the industry and in line with production costs. External advantages were derived from the abolition of excise duty and the generally buoyant market.

However, the buoyancy reflected in the 1975 annual report began to decline as inflation related to the oil boom continued apace. Also, in the 1977 UNTL annual report the problem of power supply was first mentioned, along with a remedy: the ‘purchase and installation of a generating plant with a capacity to satisfy all our needs. When the standby generating plants are installed, full production will be restored.’ The installation of this generating plant was completed in October 1978.

Nigerian–Chinese worker relations

One aspect of production that strengthened working relations between Nigerians and Chinese at UNTL was the presence of Chinese textile specialists who instructed Nigerian workers in textile design techniques and in the use of engraved rollers to print textiles (Figure 5). One man from Hong Kong, Mr Tung, worked in the engraving department in the early 1980s and instructed Nigerian Youth Corps workers in the processes necessary ‘before designs were transferred to rollers, which included color separation, photography, film processing, and the transfer of designs from film to copper rollers, after which designs were engraved on the rollers’ (Maiwada and Renne Reference Maiwada and Renne2013: 181). Salihu Maiwada, a Youth Corps volunteer at the time, noted Mr Tung's attentiveness to his work at UNTL and his helpfulness to others. Mr Tung appreciated the Nigerian environment and painted several landscapes, which were displayed in an exhibition held at the Ahmadu Bello University library in Zaria.

Figure 5 Chinese and Nigerian designers working at the Supertex Printing Mill, Kaduna.Footnote 14

The close collaboration between Nigerian and Chinese workers and management contributed to the success of UNTL, which continued to operate at a profit through the early 1990s, as Cha Chi Ming indicated in his chairman's statement in the 1991 UNT Plc annual report:

The Company has now become the first textile manufacturer in Nigeria to record a turnover of over N1b [1 billion naira] during the past year … The impressive record of your Subsidiary Companies at Gusau, Funtua, and Kaduna had also contributed immensely to this high performance of the Group during the year 1991.

Aside from good Chinese–Nigerian worker–management interactions at the UNTL mill in Kaduna, good relations were facilitated through a range of culturally appropriate actions:

Industrial peace and harmony within the Group had remained a characteristic of Union/Management relation[s] throughout the year 1991. The three tier long service award for those veterans who had attained a record of fifteen, twenty and twenty-five years with the company was marked with the usual ceremony. Sallah, Christmas and Annual leave were all enjoyed with a 15% sale discount to employees who needed some cloth for those occasions. Agreements reached with Unions on medical facilities, leave and transport allowances, Out-of-Station and Night Duty Allowances, Housing and Food subsidy were faithfully implemented to the satisfaction of staff and workers.Footnote 15

Nonetheless, company profits became increasingly difficult to maintain in the face of the high price of black oil for the company's power-generating plants and the increasing presence of imported Chinese textiles.Footnote 16 By the late 1990s, Chinese textile companies had set up offices in Lagos and Kano, while Nigerian traders and businessmen set up offices in Guangzhou, China (Bodomo Reference Bodomo2012; Haugen Reference Haugen2012; Lyons et al. Reference Lyons, Brown and Li2008; Renne Reference Renne2015). While UNT Plc mills were forced to stop production in October 2007, the company managed to pay entitlements to all their laid-off workers, as was noted in the 2007 annual report: ‘The year 2007 witnessed effective handling of industrial relations matters. It was toward the end of the year that operations of the Kaduna mill were temporarily suspended and workers were paid redundancy benefits as agreed between management and union.’ At that time, all parties involved were hoping for a government programme to resuscitate the Nigerian textile-manufacturing industry, which had – and continues to have – broad political support (Adama Reference Adama2015; Ahmadu-Suka Reference Ahmadu-Suka2018; Aremu Reference Aremu2015; Williams Reference Williams2011a).

Consequences of the Cotton, Textile and Garment Development Fund for UNT Plc

This political support led to the Nigerian government's ongoing attempts to revive the industry, most notably through the 100 billion naira Cotton, Textile and Garment Development Fund. The reopening of the UNTL mill in Kaduna in December 2010 raised the hopes of former UNTL mill workersFootnote 17 and the fund enabled UNTL managers in Kaduna to hire over 900 workers – involved in ‘Production, Administration, Accounts, Engineering, Computer, Spinning, and Weaving’ – as well as to buy new spinning and weaving equipment (Ahmadu-Suka Reference Ahmadu-Suka2011). This number reflects approximately a quarter of the mill's former workforce. Yet, by April 2013, some workers had been laid off due to poor market conditions, irregular electricity and a shortage of cotton:

A textile worker in Kaduna, Ibrahim Ezekiel, while speaking on the plight of textile workers, said:

Our company [UNT Plc] has sent us away. We are now on a three-week compulsory leave. Our company was reopened for business in 2010 by Vice President Namadi Sambo. Since that time, the company has not operated at optimal capacity. What we are doing here are spinning and weaving while the final printing is done in Lagos. There has been shortage of cotton and the situation in the country is so bad that the only option left for our management was to send us on a three-week compulsory holiday. We are on holiday because the company can't produce anything for now in spite of the intervention fund … Unlike countries like China where government moderates importation of finished goods, Nigeria's borders are porous …Footnote 18 Another reason our companies can't compete with companies in other countries is the foreign companies have access to frequent electric supply with low bills. We don't have constant electricity in Nigeria and the bills are also high which makes our company, owned by Chinese, to run the business at a loss. (Isuwa Reference Isuwa2013)

Two years later, while revival funds had continued to be released, the problems facing the industry in Kaduna undermined the reopening of other textile mills there, which have remained closed (Ahmadu-Suka Reference Ahmadu-Suka2011; Aremu Reference Aremu2015). The UNTL mill in Kaduna has continued to manufacture cotton thread and plain cotton cloth, albeit on an intermittent and reduced scale (Figure 6), while the cotton used for its manufacturing in 2017 was obtained from Niger and Cameroon. Similarly, the associated UNTL Supertex Limited mill, which specialized in higher-quality textile prints, closed in 2007 but reopened after some of the 2010 textile revival funds were distributed to UNTL. However, in 2017 the mill was limited to the manufacture of polyester woven materials used in mattress covers.Footnote 19

Figure 6 Production of baft cotton fabric at the UNT Plc textile mill in Kaduna in 2017. Photograph courtesy of Bénédicte Kurzen.

Thus, despite the government's efforts at providing funds, the textile-manufacturing industry has not recovered (Olakitan Reference Olakitan2015). In July 2016, the distribution of the remaining 40 billion naira from the Cotton, Textile and Garment Development Fund was suspended. Hadiza Olaosebikan, a Bank of Industry spokesperson, remarked that the government ‘realized that the challenges facing the sector [are] more than finance’ (Agbese et al. Reference Agbese, Alabi, Ahmadu-Suka and Iloani2016). In addition to the problems of irregular electricity, outdated machinery and smuggled textile imports (Burgis Reference Burgis2015), the difficulty in acquiring raw cotton has continued, as the director of the Kaduna Chamber of Commerce, Industry, Mines and Agriculture, Usman Saulawa, observed:

We seem to be much more concerned about textile industries and not giving emphasis to cotton production. If you observe, the cotton production has drastically gone down, a number of cotton farmers are either trying to survive or have directed their efforts towards doing other things. The cotton belt from Gusau in Zamfara State to Funtua in Katsina State, part of Kano, Bauchi, Gombe up to Maiduguri in Borno State is now a thing of the past. (Agbese et al. Reference Agbese, Alabi, Ahmadu-Suka and Iloani2016)

Indeed, the difficulty of obtaining raw cotton was noted in 2011 by Madeline Wong, the Cha Group chair, and she ‘appealed to the Federal Government to intervene and facilitate the availability of quality cotton in the country to enable the company [which included UNT Plc] to reach its target output and take advantage of the export market’ (Williams Reference Williams2011b). While the Raw Materials Research and Development Council, in collaboration with the Institute of Agricultural Research at Ahmadu Bello University in Samaru, distributed improved SAMCOT varieties of cotton seeds to cotton farmers in nine states in 2015 and 2016 (Agbo Reference Agbo2016), the better prices paid for soya beans, sorghum and maize have led some to abandon cotton farming. Indeed, farmers in Zamfara and Katsina states cited low cotton prices and difficulties with obtaining improved seeds in 2016 as the main factors undermining government efforts to increase cotton production (Mahmud Reference Mahmud2016; Umar Reference Umar2016). However, in 2017, this situation began to change as prices paid for cotton increased. As one large-scale cotton farmer and dealer in Katsina State, Alhaji Kamilu Kankara, observed: ‘Many are of the belief that it is more profitable to cultivate maize than cotton but not this year’ (Mahmud Reference Mahmud2017). Consequently, government agencies increased their support for cotton farming in 2018, facilitated by the Anchor Borrowing Programme, a federal programme established in 2015 and funded by the Central Bank of Nigeria. It provides ‘smallholder farmers … [with] loans ranging from N150,000 to N250,000 to assist them in procuring necessary agricultural inputs such as seedlings, fertilizers and pesticides, to help boost agricultural outputs and productivity’ (Onuba Reference Onuba2018). This programme has enabled farmers in Katsina to access improved cotton seed as well as fertilizers and pesticides (Mahmud Reference Mahmud2018).

Yet two problems have affected the prices that cotton farmers are paid. Many use polyethylene bags for holding picked cotton. However, polyethylene fibres from these bags contaminate the cotton lint so that when yarn or fabric made with it are dyed, the colour is not uniform. ‘Nigeria's cotton is known internationally as poly contaminated’ (RMRDC 2004: 4), and consequently Nigerian farmers receive lower prices for their cotton. According to Alhaji Sa'idu Adhama, the owner of Adhama Textiles & Garments Industry Ltd in Kano, using jute or kenaf rather than polyethylene bags to hold seed cotton would solve this problem.Footnote 20 While the Ministry of Agriculture has plans to promote growing kenaf as a substitute for jute, nothing has been done to date despite the expense of importing jute bags.Footnote 21

The other problem, mentioned by several farmers, is their reliance on foreign markets for cotton sales. ‘This improved price we are enjoying is largely controlled by the international market and if we do not improve our local consumption of the produce, I bet you [that] in no distant time, the price will crash again’ (Mahmud Reference Mahmud2018). In other words, farmers believe that the textile-manufacturing industry in Kaduna and Kano should be revived if high prices for cotton are to be maintained.

Conclusion

The Cha Group's attempts to establish and maintain textile manufacturing exemplify a business model for productive Chinese–Nigerian relations that has been characterized by efficiencies of manufacture and marketing, astute adjustments to changing economic circumstances, and respect for Nigerian government programmes and worker needs. Yet as a multinational conglomerate, the Cha Group also has respect for the bottom line. When, despite various innovations and renovations, it could not operate profitably, the company expanded its textile business in Nigeria to the marketing of its Da Viva® brand through authorized dealerships, which sell high-quality digitally printed cotton textiles in Nigeria. This situation puts the Cha Group officials in Nigeria in the awkward position of attempting to maintain UNT Plc textile mills in Kaduna and Ikorodu-Lagos while also marketing Da Viva® textiles that compete with UNT Plc products.

Furthermore, the combination of a twenty-first-century decline in Nigerian textile manufacturing and the increasing presence of imported Chinese-manufactured textiles in Nigeria has also contributed to Nigerian textile traders’ and workers’ concerns about the dominance of Chinese companies’ textiles and traders in the Nigerian market. Yet there is some common ground based on shared interests for joint Chinese–Nigerian efforts in re-establishing textile manufacturing in Nigeria, with considerable political support on the Nigerian side for Chinese–Nigeria textile-manufacturing collaboration. President Muhammadu Buhari, speaking to a delegation of foreign investors at the State House in Abuja on 8 July 2015, noted the need for his government's resuscitation of the textile industry and agricultural sector (Wakili Reference Wakili2015; see also Adama Reference Adama2015).

Indeed, the reopening of textile mills would support Nigeria's agricultural capacity for cotton production through increased demand. It might also be possible, with Chinese collaboration, to develop kenaf production for the manufacture of bags for harvesting seed cotton, which would reduce the problem of polyethylene-contaminated cotton lint.

However, considering the difficult experience of the Cha Group in Nigeria, it seems unlikely that the Chinese government will directly take on the renovation of state-owned textile mills in Kaduna and Kano. Indeed, there is an apparent contradiction in China providing expertise for improving textile manufacturing and cotton production while exporting quantities of manufactured textiles from China to Nigeria. It seems more likely that Chinese support for infrastructural improvements could help revive textile manufacturing in Nigeria, something that the UNTL director Cha Chi Ming often mentioned in his annual reports. Such infrastructural improvements could facilitate textile production by UNT Plc and its affiliated mills in Nigeria in the twenty-first century and would enable textile mill workers and traders, as well as Nigerian cotton farmers, to take fuller advantage of the enormous consumer demand for manufactured textiles in Nigeria and in West Africa more generally.

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this article was presented at the Africa–China Conference on Infrastructure, Resource Extraction and Environmental Sustainability, held at the University of Michigan in April 2017. I would like to thank Omolade Adunbi and Bilal Butt for their organization of the conference and its manuscripts as well as the staff of the Ministry of Information, Kaduna, and Bénédicte Kurzen for permission to use her photograph. At Ahmadu Bello University (ABU) in Zaria, Salihu Maiwada and the staff of the Department of Industrial Design and the librarians of Kashim Ibrahim Library helped with archival resources, while Salihu Dadari, Department of Agronomy at ABU, Sa'idu Adhama, Adhama Textiles Industry in Kano and staff at UNT Plc in Kaduna provided informative interviews. Thanks also go to Hassana Yusuf for her excellent research assistance.