In the winter of 1714 a violent incident disrupted the routine of the Royal Chapel in Madrid. Armed with two pistols and a guadixeño (a large Andalusian knife made in Guadix), Francisco Díaz de Guitián, second trumpet of the chapel, tried to kill the first organist José de Torres just outside the palace. Fortunately, the royal trumpeter missed his target and was immediately taken into custody in the Cárcel de Corte, the modern-day Palacio de Santa Cruz, near the Plaza Mayor. The reason for such a dramatic disturbance has long been an enigma.Footnote 1

The discovery of new documents and music prints now places Díaz de Guitián's crime in surprising relation to the development of the musical press in the early eighteenth century. Among the files belonging to the Consejo de Castilla, which among other important duties had to grant legal permission for the printing of a book, a modest application made in 1743 has been preserved. This document, asking the king to grant a new privilege to engrave music, reveals itself as a key source in the modern history of Spanish music printing.Footnote 2 The relevance of this source is not only based on the fact that it contains two complete and hitherto unknown organ scores (one by José de Torres and the other by Manuel Marín), but, even more importantly, because it includes as a legal precedent a complex lawsuit concerning the printing privilege for a new book entitled Arte de cantar. This dispute over the publication of a musical treatise took place about three decades earlier and involved the same Díaz de Guitián, as its author, and José de Torres, who defended his privilege against Díaz's wish to create a new music press. The legal proceedings of this first lawsuit (also accompanied by an unknown print, in this case a recitative and aria from a serenata by the court composer Antonio Literes) open new perspectives onto crucial aspects of the history of music printing in Spain.

In spite of the growing number of documentary contributions, the Spanish eighteenth century continues to be a blind spot in current print research, especially if compared with the interpretative efforts devoted to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote 3 Moreover, this same pattern applies to the specific area of music printing studiesFootnote 4 and especially to the early eighteenth century and the press of José de Torres.Footnote 5 But beyond the ritual laments about the paucity of Spanish eighteenth-century editions, some recent contributions show how detailed bibliographical work on prints can successfully integrate philological source studies that are traditionally centred on manuscripts.Footnote 6

The scarcity of musical prints in Spain until the late eighteenth century has usually been considered the result of the backwardness of a country unable to develop a market comparable with that of other European nations such as France, Germany or Italy. Consequently, the development of the musical press in Spain was interpreted under the banner of a struggle against adversity in which the enlightened figure of the music publisher is identified as epic subject of the historical narrative. José de Torres could be considered a case in point, a heroic figure of what has been called ‘the typographical ancien régime’, a period prior to the extraordinary expansion of music publishing from 1800 onwards.

Torres was indeed a central figure in Spanish music in the first half of the eighteenth century. Educated at the choir school of the Royal Chapel in Madrid in the 1680s, he began his musical career as an organist there, officially taking over as head of the chapel in 1720. His influence and prestige were linked not only to his musical talent and position at court, but also to his musical press, which enjoyed a virtual and powerful monopoly until his death in 1738. The received image of Torres has been that of a progressive modernizer, fostering music precisely through such initiatives as the launching of a musical press. The biographical article on Torres in the influential Spanish version of Riemann's music dictionary remains a classic example of this view: ‘Torres worked with enthusiasm to safeguard the Spanish tradition in sacred music, for the sake of which he even founded the ‘Music Press’ [Imprenta de Música]. Torres was not like other contemporary Spanish composers who turned their backs on the Italian musical art that was renewing all European music of the time. On the contrary, he appeared to be an admirer of the new paths of art, protecting young students so that they could travel to Italy and subsequently transmit these ideas to Spain.’Footnote 7 But, as I suggest in the present article, the story to be told about Torres's press is different: in a way it is a darker one, mixing shadows and lights. Going beyond the biography of Torres, I will deal with issues such as patronage and promotion at the Royal Chapel (a key institution in these years) and the emergence of a public sphere in music visible in such aspects as the new relationship between professional and amateur musicians in early eighteenth-century Madrid. Taking a broader view, my interest is focused on the impact of print culture on music in Spain through the methods of cultural and material history such as those developed by historians of the book.Footnote 8 In the context of this rich historiography, I shall pay special attention to the complex relationship between scribal and printed representation and transmission so important in the Spanish Golden Age, and to the tensions aroused between established traditions and the eruption of a new music press around 1700. Finally, I shall address crucial questions such as the shaping and control of the Spanish musical discourse of the time. The article, which aims to cover the main activities of the music press in Spain during the first half of the eighteenth century, is divided into three parts: first, a summary of the first lawsuit and a preliminary assessment of its main implications for the music-publishing business in Spain; second, a general study of all known music prints by José de Torres between 1699 and 1736 in their broader editorial context; and third, as epilogue, the discussion of the 1743 application for a new music press in Madrid from the perspective of the final replacement of music typography by engraving.Footnote 9

Conflict of Privileges: The Lawsuit concerning Díaz de Guitián's Tablature

Together with two other members of the Royal Chapel (the soprano Pedro París y Royo and the singer Miguel Martín), José de Torres (at the time organista principal of the chapel) started the Imprenta de Música in 1699 with the luxurious print of Destinos vencen finezas, a theatre piece by the Peruvian Lorenzo de las Llamosas with music by Juan de Navas, the first harpist of the chapel. Nothing is known about the precise relationship between the three musicians named (who appear only in this first print) and how the new music press started, but it is clear that the enterprise has to be related in some way to the patronage of Queen Marianne von Neuburg, the wife of King Charles II, the last Spanish Habsburg ruler, to whom the edition was dedicated. The main arguments given in the Introduction for establishing music typography in Madrid were the emulation of ‘the first courts of Europe’, the idea that the medium of print was a particularly suitable way of immortalizing writing and the practical need to satisfy the demands of aficionados.Footnote 10 From a European perspective it is striking that this new music press should start by using typography, since by 1699 it was an outdated technology. The fact that Germany was the only exception in the general move from musical typography to engraving around 1700 could be another argument for linking the patronage of Marianne von Neuburg to the Imprenta de Música.Footnote 11

Through the Memorias políticas y económicas published in 1787 by Eugenio Larruga it is known that Torres received a special exemption in 1719 which authorized him to import a quantity of paper free of import taxes for his printing business. Torres's argument for this franchise was technological: he claimed to have invented a new printing device called entablatura that enabled him to print chords with compound types on a single musical staff. It was argued that this new technique needed special fine paper that had to be imported.Footnote 12

Until now, little has been known about the general legal situation in which Torres's print shop operated, nor about the exact nature of the lawsuit that Torres brought against Díaz de Guitián.Footnote 13 A legal copy of the original privilege, used at the proceedings for the lawsuit, confirms that it was the Habsburg King Charles II who had on 25 January 1700 conceded a printing privilege to José de Torres, assuring him exclusive rights for the printing of music for ten years. The privilege was renewed by the new king, Philip V, in 1710 for another ten years, establishing a fine for the illegal printing of music of fifty thousand maravedís in addition to the confiscation of the music types. It remained in force until Torres's death in 1738.Footnote 14

Music printing had been weak in seventeenth-century Spain: promising initiatives such as the establishment of the Madrid-based Typographia Regia in 1598 (which published some well-known music editions by Victoria, Lobo and Rogier), the music typography designed in Saragossa by Sebastián Aguilera de Heredia or the print shop founded by Artus Taberniel in Salamanca did not have a lasting influence.Footnote 15 With the help of its special privilege, the Imprenta de Música had, on the contrary, a sustained impact for several decades, and it is not difficult to understand that his monopoly on every practical and theoretical music edition must have given Torres an extraordinary position.Footnote 16 It should be noted that contrary to other print privileges that stated precisely the nature of the protected work, in the case of Torres the royal patent granted him a ‘licence and privilege for the period of ten years to print at [his] expenses all things pertaining to music’.Footnote 17 As we shall see, the effective commercial monopoly that resulted from this general privilege resembles similar situations in other European courts such as the publishing activities of English musicians like William Byrd or Thomas Morley (both members of the Chapel Royal), who worked with different printers using their privilege to print any kind of music, or the French case of the Parisian Ballard family, who effectively transformed their general privilege into a virtual monopoly, bringing lawsuits against any other initiatives that involved music printing.Footnote 18

Five years before his attempted crime Díaz de Guitián had published a curious Memorial Sacro-Político y Legal in which he invoked royal protection with the argument that ‘with great labour and study he had discovered a new and very easy music method for singing, accompanying and composing’.Footnote 19 In his ponderous apologia, full of classical and theological references, nothing is said about the precise nature of this new musical system besides that ‘it has been proven that this new method is the most legitimate for music, and for the same reason the easiest, as has been shown by the experience of many students who were and are presently taught by the supplicant at his home’.Footnote 20 This publication was in fact the first legal move by Díaz de Guitián to try to circumvent Torres's privilege. He presented his printed Memorial to each member of the Consejo de Castilla, which was the supreme authority in printing matters, arguing that from his newly invented method there derived ‘great public benefit and usefulness, both in the political and in the sacred spheres, which is more extensively proven in the printed report that I have put in the hands of every minister of Your Council’.Footnote 21

The treatise Arte de cantar was probably finished in 1707 or early 1708, according to the autograph of Juan (Bonet García) de Paredes, chapel master of Toledo Cathedral, who on 16 April 1708 signed a certificate of approval for the treatise, which was added as support for the legal proceedings. Juan de Paredes defends the new treatise ‘for the use and education of music lovers who … will not be musicians by profession’.Footnote 22 A second approbation – also preserved in the trial file and signed in Madrid on 9 May 1710 by Juan Pérez de los Cobos, chapel master in the southern town of Lorca – shows how Díaz de Guitián tried to broaden support for publication of his music method.

The legal process concerning Arte de cantar lasted around a year. On 24 March 1710 Díaz de Guitián presented his first request, and a few weeks later Torres started legal proceedings against it. From the beginning Díaz de Guitián not only wanted to publish his Arte de cantar, but – and this was crucial, as the method implied a new script or tablature – he also requested permission to establish a new music press in his own house. This would allow him to supply his music students with pieces of music properly produced according to his method. Consequently, he also claimed a privilege to protect his business and his allegedly revolutionary invention. A legitimate claim, he argued, taking into account ‘the numerous gatherings of students who come to my home with the aim of acquiring [musical proficiency]’, and ‘once this has been met, they need to have secular and sacred works, put in the order and rules of the said method, to their greater advancement and exercise, as well as to be able to teach others. To this end, the most convenient way is to allow me to have a press at my home.’Footnote 23

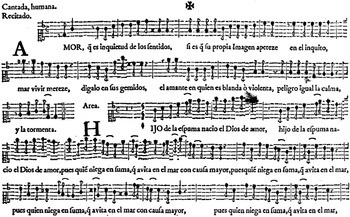

As part of the legal proceedings, Díaz de Guitián handed in a practical example of his tablature: the printed vocal and accompanimental parts for the hitherto unknown serenata ‘Hijo de la espuma’ by Antonio Literes, together with its manuscript transcription into the new notation for each individual part. In the absence of any explanation, it affords at least an approximate idea of his system, which is clear from a comparison of the vocal part with its transcription presented in fair manuscript copy (see Figures 1a and 1b):

• Pitch is represented by numbers that correspond to a chromatic scale on C starting on 0 and reaching 9 (=A). B♭ is represented by roman numeral X (to avoid the impractical use of two numbers), and B♮ by H.Footnote 24

• Ascending or descending intervals are indicated by similar ascending or descending slashes between the numbers.

• The two octaves of the vocal range are distinguished by two horizontal staff lines (traced in red ink in the original) into which barlines are regularly inserted.

• Rhythmic indications are generally written above small dots in the case of a pause or above the ciphers denoting a given sound. The rhythmic signs used are: a full or half black dot for a semibreves and minims respectively, a cross for crotchets, a double dot for quavers and a sign similar to K for semiquavers; prolongation dots are also used.

• Tonality appears to be indicated by a combination of ciphers: thus the Dorian G minor of the opening recitative and aria is represented by 7 (=G) below an X (=B♭), the whole between brackets.

• Other signs are related to phrasing, such as slurs and the simple or double vertical strokes placed to indicate articulation inside the bar, which offer interesting insights into the performing practice of the time.

Figure 1a Antonio Literes, vocal part of the secular cantata ‘Hijo de la espuma’ (Madrid: Imprenta de Música, 1708). Madrid, Archivo Histórico Nacional, Consejos 26565-12. Used by permission

Figure 1b Francisco Díaz de Guitián, manuscript tablature transcription of Figure 1a, using red ink for the horizontal lines. Madrid, Archivo Histórico Nacional, Consejos 26565-12. Used by permission

Unfortunately, the tablature does not give information about continuo performance: the accompaniment has just the bass line, indicating the intervals of the figured bass by adding the continuo ciphers which are distinguished from the tablature numbers by a small dot on top. Guitián's didactic method merely transcribes in a simplified abstract form the standard staff notation of each part of the piece separately, thus excluding score representation or finger notation, the two main advantages of tablature. In this sense, Díaz de Guitián's proposal belongs to the type of reform tablature which wants to simplify the ordinary notational system for the benefit of beginners – a kind of tablature that also includes, some thirty years later, the example of Rousseau's ‘nouveaux signes pour la musique’.Footnote 25 It is interesting to consider that the views that developed in France for and against this project are basically the same as in the Spanish case. On the one hand, Rousseau wants to serve the two or three thousand Parisians ‘avec disposition’ who are excluded from music-making by the complexity of the ordinary notational system.Footnote 26 On the other hand, the question of compatibility of the reformed and traditional systems and the problems raised by existing pieces of music edited in the old way are presented as a strong practical argument against any reform.

The lawyer Francisco Castro, on José de Torres's behalf, opposed the attempt to found a new music press in Madrid, arguing that the alleged system of notation could not be new since the basic rules of music were not subject to any progress. Therefore the art of music ‘cannot be advanced nor be innovative in relation to which has been received and practised from the time of its first inventors. What [Díaz de Guitián] has done is only to change the forms in which the consonances and rules are understood …, which commonly are called solfas, and to replace them with numbers which explain the same concepts, without any progress being made.’Footnote 27

Torres's defence was twofold: on the one hand, he argued that the alleged new system was not an invention, but just a peculiar kind of transcription that was already covered by his printing privilege. On the other hand, Torres's party also argued against allowing Díaz de Guitián's ‘invention’ to be introduced; it was a dangerous innovation that had the potential to put traditional music notation in danger. Inconsistent as this position was from a logical point of view, it was a shrewd move to try to overcome Díaz de Guitián's arguments: at best, it would involve the project as a whole being rejected; at worst, if the proposal was accepted, any resulting material would have to be printed at the Imprenta de Música. The case made against Díaz de Guitián's innovation reveals aspects of Spanish musical discourse involving its tight systems of control which are worth considering in some detail.

Díaz de Guitián's main consideration concerns the existence of the music lover (‘aficionado’), a kind of musician about whom very little is known in Spain before the end of the century.Footnote 28 ‘Aficionado’ appears in the legal arguments of the lawsuit in opposition to ‘profesor’, the educated professional musician who was archetypically represented in Spain by the figure of the maestro de capilla, the chapel master. From the point of view of Torres's defence, if music-lovers are to be taught through a completely new system, then they will cease to use the written and printed books notated in solfa, and so it should be prohibited:

El nuevo méthodo de que la otra parte se dice autor es una novedad de mucho perjuicio a los profesores de música que no se debe permitir porque los que la aprendieren por él no podrán en ninguna forma entender los libros que con tanto acierto sean escripto y de que usan las Santas Iglesias de estos Reynos ni las obras que sean impreso e imprimen en todos los comercios por explicarse todos con unos mismos caracteres y figuras de que se aparta la otra parte inventando dicha cifra particular queriendo persuadir que puede ser de útil alguno contra la practica universal observada inconcusadamente por tantos siglos.

The new method of which the other party claims to be the author is a novelty of great nuisance to the professional musician, which should not be permitted because all those who will learn music through it will not in any way be able to understand the books which have been written with so much wisdom and which are used in the Holy Churches of these Kingdoms, nor the works which have been printed in all shops, as they are all presented using the same characters and figures from which the other party departs, inventing this particular tablature and trying to convince us that it can be of some use against the universal practice which has been observed without discussion for many centuries.

In order to be printed, Díaz de Guitián's Arte de cantar needed to pass the censor with an aprobación or censura signed by an expert who testified that the book was of use and value (and, of course, did not offend the Christian faith). In addition to the legal text issued by the official censor from the Royal Council and published as a part of the front matter in every book, authors looked for more approbations as a sign of prestige.Footnote 29 In defence of his book, Díaz de Guitián argued that besides the already mentioned aprobaciones by Paredes and Pérez de los Cobos, he had also obtained certificates of approval from Juan de Navas, the above-mentioned harpist of the Royal Chapel, and from José de Torres himself. But both were withdrawn under unclear circumstances.

The legal proceedings around these withdrawn approbations afford unexpected insights into how these texts were used to promote or to block a book (and a professional career). Guitián's attorney asked both Torres and Navas to make declarations under oath concerning their alleged approbations and the reasons for their withdrawal. Navas declared that the author visited him at his home and showed him the approbation by Juan de Paredes. At Guitián's request he gave his consent without looking properly at the document, given his many commitments. Later on, ‘having examined carefully some drafts and papers of the said music written by the aforementioned Don Francisco [Guitián], he found that he did wrong in giving him his aforesaid approbation, so that he asked to recall it, which in effect he did’.Footnote 30 In Torres's affidavit, he admitted that the corrections to a draft approbation presented by Guitián were in his own hand, but that he did not recall having signed it. Torres made some changes to expressions that were unacceptable to him and as a friendly favour to his colleague:

Es verdad que Don Francisco Diaz de Guitian, músico instrumentista de dicha Real Capilla le hizo grandes instancias asi pasados para que le aprobase un método que él decía ser de música para lo cual trajo un borrador aprobación hecha a su modo, que es el que está presentado en estos autos y en el había algunas cosas que repugnaban a la razón, por cuyo motivo el declarante no lo firmó y sólo en ella por la amistad y consuelo de dicho Guitian enmendó algunas entrerenglonaduras que le parecieron más conformes a la razón y no se acuerda que le haya firmado.

It is true that Don Francisco Díaz de Guitián, intrumentalist of the said Royal Chapel, had often asked in the past that [Torres] approve his method, which he said was a musical one and for which he brought an approbation he had drafted himself, which is the draft presented at this summons and which contained some things that contradicted reason, so that the deponent did not sign it, and only out of friendship for the aforementioned Guitián, as well as to console him, did he make some corrections between the lines which seemed to him more akin to reason, and he does not recall having signed it.

The dispute surrounding Guitián's work demonstrates very clearly that the major disciplining function assumed by the Spanish system of censure also applied in the field of music. It was the highly conservative hierarchy of chapel masters that finally – and very effectively – controlled what could or could not be published about music.Footnote 31 Generally speaking, the rhetorical and conventional content of approvals tell us little except for the way in which authority is imposed. Who signs is essential: as we shall see, a series of approbations in a given time and place form a reconstructable network. The arguments against Díaz de Guitián, a contentious intruder in a stable existing structure of interests,Footnote 32 shrewdly evoke his eccentric position, and he was unable in the end to achieve an approval from any reputable Madrilenian chapel master:

Sin que hasta ahora haya exhibido ninguna [aprobación] como se ha referido de los maestros conocidos de las capillas de esta corte, por saber que ninguno se la ha querido dar, porque no sólo no se adelanta en dicho método la enseñanza y aprovechamiento de este arte, si no es que se siguieran repetidos perjuicios de que no han querido ser causa ni motivo.

So that until now he has been unable to show any [approbation] as has been reported from the reputed chapel masters of this city, as we know that no one wanted to give him one, not only because teaching and improvement of this art are not advanced by this method, but also because they did not want to be the cause or instigators of the repeated nuisances that may follow from it.

As a legal argument for his own printing privilege, Díaz de Guitián defended change and improvement as social virtues that should be protected by political power: ‘because it is against any political and public advantage to constrain the liberal professions to narrow precepts when in matters of decent or similar pastimes progress is not obstructed but rewarded and even encouraged for the greater profit of teachers’.Footnote 33

Finally, on 7 March 1711, the Royal Council resolved against the establishment of a new music press. A legal report by a member of the council issued a few weeks before the ruling shows the legal reasoning (which excludes any mention of the printing privilege) and reveals a great deal about the hegemony of the institutional system of ecclesiastical chapels and the notions of order, use and public interest that were applied to music. On the one hand, Guitián's proposal is praised as a new didactic music method that actually could be of use to people who want to learn music as entertainment without investing too much time. On the other hand, the method would be useless for professional singers and instrumentalists. The judge's fear that this novelty would render the old notation and all prints using it redundant makes him decide against Guitián's proposal under the general argument of its lack of utility and its serious potential disruption to the music profession.Footnote 34 Given this precedent, it is not surprising that the Arte de cantar was never published and that no other music editions by Díaz de Guitián are known to have been printed. Moreover, it was no doubt an effective warning to any other possible challenger.

The Imprenta de Música: Books, Scores, Sheet-Music

Torres's privilege and his lawsuit against Díaz de Guitián place his publishing activities under a new light. If I restrict my research here to the music productions of his press, it is important to bear in mind that it produced many other books which had nothing to do with music, such as sermons, medical treatises (next to music one of the main published subjects), historical and legal monographs, and so forth.Footnote 35 The Imprenta de Música also played an institutional role at the court of Philip V, as is shown by the 1707 edition of the two-volume index of books forbidden by the Inquisition, among other political prints.Footnote 36 It is difficult to know to what extent and under what circumstances Torres was involved in these non-musical prints. Printers who operated as independent publishers, such as Bernardo Peralta, occasionally used the types from Torres's print shop, as can be deduced from the title pages of several editions and the use of typographical ornaments belonging to the press.Footnote 37 Other names that appear in connection with the Imprenta de Música are those of Miguel de Rézola and Juan Sáez Ocañuela. Unlike these men, Torres was not a professional publisher, but a court musician who owned a musical press, which he directed simultaneously with his numerous duties in the chapel.Footnote 38

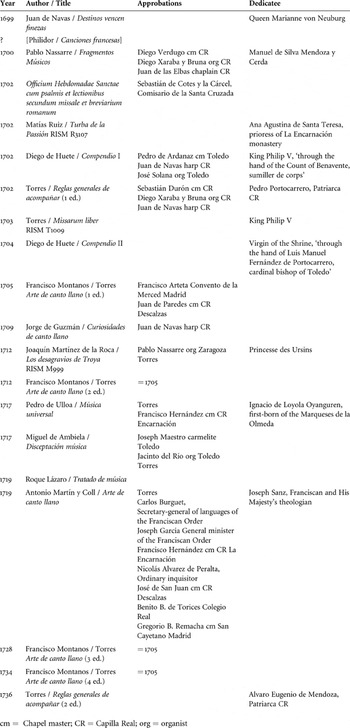

A consideration of the music production of the Imprenta de Música as a whole must make a formal distinction between books and scores, on one side, and small individual pieces of sheet music, which will be treated separately. The production of the first category falls into three distinct groups: (1) music tutors; (2) liturgical music prints; and (3) theatrical prints (see Table 1).

Table 1 Books and major music publications by the Imprenta de Música

cm= Chapel master; CR=Capilla Real; org=organist

The largest class is that of music tutors and includes Nassarre's Fragmentos (a basic introduction to plainchant and counterpoint), the two parts of Huete's harp tutor, Torres's two editions of his own thoroughbass treatise, four editions of Montanos's book on plainchant (which includes in all the editions a substantial introduction to modern solfeggio by Torres) and both Guzmán's and Martin y Coll's treatises on plainchant (the last of these also having a detailed introduction to solfeggio and polyphony). Ulloa's treatise on music remains somewhat apart in this group because his speculative discourse clearly separates it from the didactic function of the practical tutor.

Liturgical polyphonic music prints in mensural notation include Torres's Missarum liber and the polyphonic turba setting by Matías Ruiz (referred to in the print as chapel master of the Royal Chapel of La Encarnación in Madrid). A special case is the 1702 print of the Holy Week Officium, the only known chant print by the Imprenta de Música. As the approbation for the book states, in this case Torres had obtained special permission in order to avoid infringing El Escorial's privilege concerning all liturgical books pertaining to the Tridentine New Prayer (Nuevo Rezado).Footnote 39

Finally, the third group includes two prints of theatre music: Destinos vencen finezas and Los desagravios de Troya. Both folio luxury prints have a distinct political and commemorative function, in connection with two birthday celebrations: in 1699 that of King Charles II at court and in 1712 that of the Infante Felipe de Borbón in Zaragoza.Footnote 40 The 1699 print (which combines the full text of the theatre piece with its forty-seven musical sections in score) was dedicated to Marianne von Neuburg, the last Habsburg queen in Spain. Thirteen years later, the situation had changed dramatically. The score of Los desagravios (which eliminated the spoken text of the piece, but included all the stage music for the interludes) was dedicated to the French party in the figure of the powerful first lady-in-waiting of the Spanish queen, Marie-Anne de La Trémoille, Princesse des Ursins, by the Count of Montemar, a general of the Bourbon army during the War of Succession (1701–1714).Footnote 41 This war, which brought the European powers into conflict on the question of the successor to the Spanish crown in 1700, had a profound effect in Spain, where it assumed the traits of a complex civil conflict between Castile and the Crown of Aragon. The international dimension of the war also deeply affected the court and nobility: long-held family strategies, as well as established loyalties and patronage systems between the Spanish and Italian nobility throughout the seventeenth century, had suddenly to shift between Austrian and French sides of the war, accommodating themselves to the changing military fortunes and the conflict's lasting strategic consequences.Footnote 42 The dedications published by the Imprenta de Música illustrate the public dimension of the print dedication and the complexity of the political shift which Torres had to make from his at first strong Habsburg connections to the need to display political loyalty to the new Bourbon king.

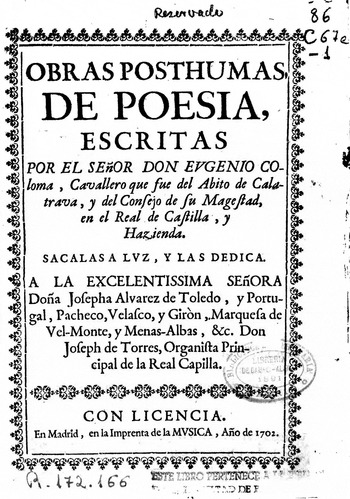

A work that falls outside the musical production of the press is Eugenio Coloma's Obras posthumas de poesía, an anthology published by the Imprenta de Música in 1702 (see Figure 2). However, this edition merits special attention because of Torres's extraordinary personal involvement; as is stated on the title-page, he acted as literary editor (an unusual role for an organist).Footnote 43 As the dedication usually required the authorization of the dedicatees, it is worth exploring their cultural and political profiles. In the case of Coloma's edition, it was Josefa Álvarez de Toledo (1681–1754), the daughter of a key political figure at Charles II's court: the Count of Oropesa, Manuel Joaquín Álvarez Toledo y Portugal, royal favourite, prime minister and notorious supporter of the anti-French party at court. In 1697 she had married Manuel Gómez de Sandoval (the future Fifth Duke of Uceda), who also ended up on the Austrian archduke's side as a result of the sudden change to Habsburg support by his father, Juan Francisco Pacheco, ambassador to Philip V in Rome (1701–1709) and a great patron of arts and music.Footnote 44 Eugenio Martín Coloma y Escolano (1649–1697) also engineered a political career under the Habsburg administration. His father had been secretary of state under Charles II, and Eugenio rose to the position of minister of the Consejo Real de Hacienda, whereas his brother Manuel Coloma, Marquis of Canales, carved out a diplomatic career under Charles II (he was appointed ambassador to London and The Hague) and ended up a powerful minister of war under Philip V.Footnote 45

Figure 2 Eugenio Coloma, Obras posthumas de poesía (Madrid: Imprenta de Música, 1702). Madrid, Universidad Complutense, Biblioteca Histórica. Used by permission

Equally significant in terms of political connections is Torres's dedication in his 1700 edition of Nassarre's Fragmentos Músicos. As the dedication states, Torres was teaching music to Manuel de Silva Mendoza y Cerda (1677–1728), Count of Galve and husband of the Eleventh Duchess of Alba, María Teresa Álvarez de Toledo. Torres writes about his student with the accustomed hyperbole: ‘to see him accompany a part at the harpsichord causes admiration, and it seems less an acquired skill than a God-given knowledge. And so I live in trepidation, for being justly proud of having Your Excellency as my pupil, your knowledge gives me cause to doubt that I could have been your teacher.’Footnote 46 The same Silva Mendoza also supported the Habsburg cause and was among the nobles who in the spring of 1706 moved over to the Austrian pretender's side.Footnote 47 As is well known, Torres, together with other members of the Royal Chapel, was temporarily suspended from duties between 1706 and 1708 under the accusation of high treason on the basis of alleged Habsburg sympathies.Footnote 48

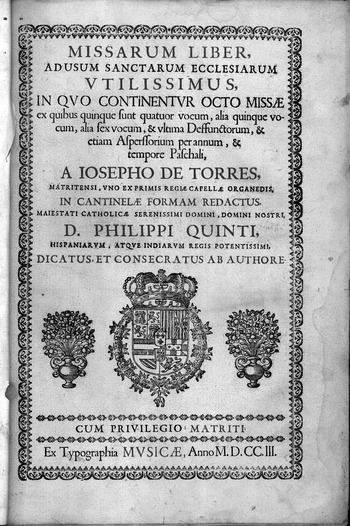

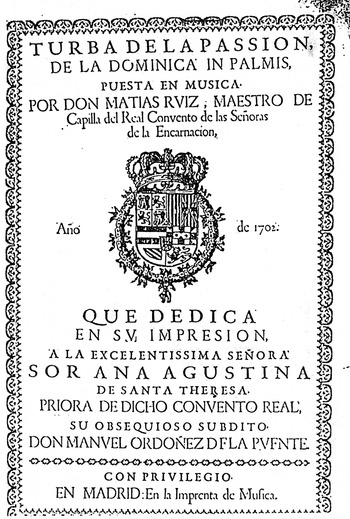

The dedication to Philip V of Torres's Missarum liber strongly emphasized the authorial status of the composer on the title page (‘dicatus et consecratus ab authore’), with special accent on his profile as a composer of sacred music of which he was ‘semper … studiosissimus’. With political opportunism, the Latin text evokes the images of Mars and Apollo to represent the king, ‘magnanimum in praeliis Martem, suavissimum quoque imitatur Apollinem’.Footnote 49 One year earlier, the first edition of Torres's Reglas was dedicated to Pedro Portocarrero y Guzmán, political head of the Royal Chapel between 1691 and 1706.Footnote 50 In the case of the dedication of the passion choirbook from 1702, specific mention is made of the act of printing on the front page: ‘Turba de la Passión … que dedica en su impresión, a la excelentíssima señora Sor Ana Agustina de Santa Teresa … su obsequioso súbdito Don Manuel Ordóñez de la Puente’. Ordóñez was also the author of one of the encomiastic sonnets in the editions of the Reglas de acompañar by Torres, where he appears as ‘amigo y compañero’ of the author.Footnote 51 Both the Missarum liber and the Turba print on the front page the royal arms of Philip V, underlining the institutional status of the editions (see Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3 José de Torres, Missarum Liber (Madrid: Imprenta de Música, 1703). Madrid, Real Biblioteca de Palacio, Cantoral 103. Used by permission

Figure 4 Matías Ruiz, Turba de la Passión (Madrid: Imprenta de Música, 1702). Cordoba, Archivo catedralicio. Used by permission

Almost all the music books include the relevant printing privilege on the title page, while some, such as Nassarre's Fragmentos, mention the privilege for the single book ‘and for everything pertaining to music for the time of ten years’.Footnote 52 In Huete's Compendio the privilege from 25 February 1698 was granted to the author for that specific work. The exceptions that do not include a privilege are Destinos vencen finezas (published with licencia around November 1699, some months before the concession of the music printing privilege), Guzmán's Curiosidades (a treatise limited to plainchant) and Los desagravios de Troya (as already discussed, a highly political score).

In terms of classification as cultural objects, the division of the music books from Torres's press that I have suggested above is fundamentally pragmatic and may seem somewhat arbitrary. Indeed, the category book is materially unambiguous in legal terms, being a print identified by a whole set of formal paratexts such as dedications or approvals, and these also apply to substantial scores such as Destinos vencen finezas, Los desagravios de Troya and the Missarum liber of 1703. But problems arise with titles like Ambiela's Disceptacion or Roque Lázaro's Tratado; these are texts produced as booklets and do not fulfil all the formal requirements of a book. Ambiela does not identify the press nor its publisher (but the typography of its music examples is undoubtedly that of the Imprenta); Lázaro gives Madrid and the Imprenta de Música as his publisher, but does not present approbations or meet any of the necessary legal requirements. Both prints are texts relating to a famous polemic about the use of an unprepared dissonance in a polychoral mass by the Catalan composer Francisco Valls: as pamphlets they are adapted to the sort of flexible and rapid exchange of texts that often escaped administrative control. Scores such as the Turba settings by Matías Ruiz or the enigmatic collection of Canciones francesas de todos los ayres, a reprint of André Danican Philidor's 1699 Suite de dances pour les violons et hautbois, fall midway between the standard music edition and sheet music. It is still not known for whom and for which use the work was reprinted, as it did not pass the censor. However, a direct connection with the court can be excluded since the distinctive marks of the original edition are erased: no dedication or prologue was included in the Spanish edition, nor is reference made to original publisher Philidor.Footnote 53

Very little is known about the actual production of books and scores by the Imprenta de Música. Interestingly, some of the statements made in Díaz de Guitián's lawsuit confirm the general assumption that the production of music prints was more or less the same as for the literary editions. It is assumed that the author will pay the press and afterwards will take care of arranging the distribution of the edition:

Cuando quiera que se le concediese licencia para que use de él, debe ser haciendo la impresión en la imprenta de mi parte manteniéndole y conservándole su privilegio, pues pagándole los derechos de la impresión tendrá la otra parte [Díaz de Guitián] la utilidad de la venta de sus obras como la tienen los autores de los libros que pagado el impresor los recogen para venderlos como les conviene y tiene mejor cuenta, y con especialidad cuando mi parte tiene los números y caracteres de que la contraria quiere usar y ha de correr por él la impresión y corrección de sus obras para que salgan a la luz como desea.

Whenever a licence is granted to him for his use it should be for printing at my [Torres's] press, maintaining and conserving his privilege, for in paying the rights of print, the other party [Díaz de Guitián] will have the utility of the sale of his works in the same way as do the authors of books, who collect them once the printer has been paid to sell at their convenience, and they benefit from this, especially since my party has the figures and characters which the other party wishes to use, and he will be responsible for the print and correction of his works so that they see the light as he wishes.

The last statement about the disposal of the desired ‘figures and characters’ seems to be bluff on the part of Torres's defence, since in all its known editions the Imprenta de Música used only three kinds of music type: plainchant square notation, stile antico polyphonic types or, in most cases, standard modern notation. Special emphasis is given by Torres to the fact that correction of proofs is the responsibility of the composer, who is expected to fulfil his duty at the press: ‘it would be not fair that the other party could own a press, for in my press he will be able the make the print, correcting the misprints before the final print run, and take it home afterwards, and enjoy the benefit that he would get from its sale, as frequently happens with the authors of books’.Footnote 54

Marketing, distribution and sales had been a problem for the Spanish book trade throughout the modern era. Little is as yet known about sales of the editions produced by the Imprenta de Música. There is interesting evidence for Torres having sent, with special permission of the Royal Council, four chests of the Reglas and the Missarum liber to Cartagena (probably Cartagena de Indias, today Colombia) and New Spain (Mexico) in 1704, about a year or two after the printing of both books.Footnote 55 With the exception of Ulloa's Música universal, no music book was advertised in the Gaceta de Madrid. Booksellers (mercaderes de libros) are named in some of the editions: Manuel Balaguer, for instance, appears as a book merchant in Madrid in Huete's Compendio (only in the second part). The four editions of Montanos/Torres were also distributed by Madrilenian merchants: Diego Lucas Ximenez (1705), Juan Estevan Bravo (1712), Francisco Laso (1728) and Juan Antonio López (1734).Footnote 56 In contrast, both editions of Torres's Reglas seem to have been sold by the author himself: a post-mortem inventory of his possessions lists ‘507 libros de Reglas Generales de Acompañar, cuarto de marca mayor cada uno a 6 reales’, which surely refers to a substantial part of the 1736 edition. Another item in the same document details ‘111 libros Pasionarios, Oficios de Semana Santa papel de marquilla a 24 reales cada uno’, which corresponds to the Officium printed in 1702; it represents the remainder of the agreed print run of 550 copies.Footnote 57

Almost nothing is known about the financial aspects of Torres's music editions. In the case of the Missarum liber, the composer asked in August 1703 for a payment of four hundred ducats ‘because of having contracted other debts for the printing of the book of masses which he has dedicated to His Majesty’.Footnote 58 For the printing of Nassarre's Fragmentos, on 6 February 1700, Torres contracted Fray Martín García de Olague, ‘religioso de la Santísima Trinidad y organista principal’ in Cuenca Cathedral, to buy in that town or district about five hundred reams of paper.Footnote 59 But this quantity seems to cover more than a single title, as it would have resulted in the astronomical amount of more than six thousand copies.Footnote 60 Three months later, Nassarre's Fragmentos was already in print, as is proved by the Fe de erratas dated 21 April.

Huete's harp tutor offers a special case, as it did not use movable type but engravings for its tablature pieces. As a harpist at Toledo Cathedral, Huete asked for financial help from the cathedral chapter to support the printing expenses.Footnote 61 But the most interesting information comes from Huete's will, which shows that he preserved at home around one hundred engraving plates of both parts of his Compendio. He also states that the book merchant Manuel Balaguer has ‘about one hundred books of the second part’, mentioning another ten copies ‘in possession of Don Joseph de Torres, organist of the Royal Chapel in Madrid’ and a ‘little box with twenty-four of the books mentioned’ which was the property of Juan Bezerrol from Toledo.Footnote 62

Sheet Music: Script and Print

While the powerful symbolic function of the Missarum liber or the theatrical scores from 1699 and 1712 that were dedicated to politically important people should not be overlooked, these music books were but a minor part of the production of the Imprenta de Música. Ultimately the main impact of the press derived from best-sellers like Montanos and Torres's Arte de canto llano, with its four editions in less than thirty years.Footnote 63 But any view of the secondary importance of music editions has to be further reconsidered when we take into account a product peculiar to the press: sheet editions of single vocal works in separate parts in oblong format. Many of these were for reduced ensembles of one or two voices, with an accompaniment suited to domestic use or for academies. But bigger ensembles can also be found in sacred pieces such as the double-choir Christmas villancico ‘Ya empieza el rumor’ in ten parts, which includes, in addition to the choir, two different figured-bass accompaniments (one of them for the organ). In any case, the use of these sheets is likely to have been flexible, given that the use of secular music in sacred contexts, and sacred in secular, was a well-established practice in the Iberian world.Footnote 64

The ephemeral modesty of this loose sheet format has made it almost invisible to research, which has taken little notice of its existence. Information about the extant sheet music prints (often incomplete and sometime anonymous) is scattered and difficult to locate in catalogues. No previous comprehensive list has been made of these prints, which are presented here as an open list, to which one hopes additions will be made in the near future. As the evidence gathered here shows, these forty-two pieces form a highly significant part of the press's musical activities and should therefore not be neglected (see Tables 2 and 3).Footnote 65 Interestingly, most of the surviving sheets (which are all unica, with the sole exception of a repeated printed copy in Guatemala) are dated at the corners of the decorative filigree of the first single page, which serves as a front page once the parts are folded. This peculiar type of single-page music edition seems to have begun in 1703, the year of the first known dated filigree.Footnote 66 All surviving title pages (dated or not) state that the given edition appears ‘con privilegio’, and many indicate the total number of sheets (hojas) of the piece, to which sometimes a publisher's number is added (see Figure 5).

Table 2 Dated sheets

[I]=Incomplete; Incipit refers to the text of the piece on the cover, if preserved; if not, the first words of the opening section are given. RISM numbers refer to the A I Series (Einzeldrucke vor 1800).

Table 3 Undated sheets

[I]=Incomplete; Incipit refers to the text of the piece on the cover, if preserved; if not, the first words of the opening section are given. RISM numbers refer to the A I Series (Einzeldrucke vor 1800).

Figure 5 (Left) Juan de Lima Serqueira, front print sheet of the secular cantata ‘En la ribera verde’ (Madrid: Imprenta de Música, 1715). Madrid, Biblioteca del Real Conservatorio. Used by permission. (Right) Attributed to José de Torres, song from the zarzuela El imposible mayor (Madrid: Imprenta de Música, 1711). Madrid, Archivo de los Duques de Alba, Caja 174/22. Used by permission

Produced over a span of roughly three decades, these sheet-music editions present many complementary aspects of continuity with extant scribal practices. Even if the uses of music copying and the mechanisms of circulation of musical manuscripts in seventeenth-century Spain remain to be explored in more detail, there is already enough evidence to give us an idea of the cultural context in which the Imprenta de Música emerged. For instance, several preserved collections of letters from different chapel masters of the second half of the seventeenth century afford a vivid picture of the active exchange of manuscripts of vocal sacred music and poetic texts for villancico and cantata settings between different urban centres.Footnote 67 The cases of the letters of Miguel Gómez Camargo or of Miguel de Irízar, chapel masters from the second half of the seventeenth century, are indicative: their circulation of musical manuscripts suggests a similar scribal community to those described for England in the Restoration period, which were concerned with the scribal publication of political discourse, poetry or music.Footnote 68 In fact, this kind of evidence points to a general pattern also found in other parts of Europe, characterized by the circulation and exchange of manuscripts in a close network of professional musicians. Chapel masters, singers and nun musicians wrote letters which – along with the communication of professional gossip and requests for poetical texts needed for the great quantity of new devotional pieces performed in different ceremonies – also included music. The material continuity between epistolary text and music, often inextricably intermingled in such collected manuscripts (preserved by users as folded sheets or pliegos),Footnote 69 corresponds to an economy of exchange in which basically one writes to perform and performs to write.

In a letter to Camargo dated January 1665, the organist Diego de Guevara y Andrada made this collegial network explicit when he introduced his petition of some devotional songs to help the sick Baezan chapel master with the following words:

Parece que sólo en ser todos de la misma facultad contraemos algún parentesco y por esta causa debemos valernos unos de otros en lo que tocare ser materia de ella misma. Dígolo porque aun no habiendo servido a Vmd. en nada ni conociéndole si no es por noticias, hoy me resuelvo a molestarle con mi carta, de que desde luego pido perdón y le suplico que atienda, que no puedo hacer otra cosa, que esta diligencia es una de las anexas a mi obligación y oficio.

It seems to me that merely by the fact of belonging to the same faculty [music] we gain a kind of kinship by which we are obliged to assist each other in matters related to the same. I say this because, not having served you in any way nor being acquainted with you except by reputation, I have decided to inconvenience you with this letter, for which I ask your forgiveness, and I beg you to consider it, because I cannot do otherwise, this mission being one that is proper to my duties and office.Footnote 70

As fascinating and informative as some of these letters may be, it is important to keep in mind that such sources afford only a limited glimpse into the practices of copying and sending manuscripts. In fact, these letters survived in cathedral musical archives like Segovia or Valladolid only by chance, as they were written on the back of the musical scores. Some hints in these letters, corroborated by the palaeographical evidence of musical scores and parts, point to the regular exchange of originales to be copied by the receiver and then returned, but also to the supply of music through professional copyists working on a commercial basis. An indicative case is that of Francisco Lizondo, a former choir boy of Segovia Cathedral, active in the 1670s in Madrid and nephew of the master of the Royal Chapel, Carlos Patiño. Lizondo supplied diverse Madrilenian monasteries with music, exported his copies to the New World to places such as Puebla Cathedral in Mexico and worked as ‘escritor de la Real Capilla’.Footnote 71 A different case is that of José Guerra, an important court copyist without musical training who also occasionally copied music.Footnote 72

Torres's profile as a major figure in Spain's musical scene around 1700 presents some striking traits in this context, which may reflect some of his personal characteristics as well as specific aspects of Spanish musical culture at the time. In a trade such as printing, where the majority of the publishers were printers connected in different ways with the musical world, Torres is an example of the reverse situation. As one of the main composers of his time, from the 1720s he officially held one of the most influential musical positions of the kingdom as Maestro de la Capilla Real. He was not only promoting his own work (twenty-one pieces are attributed to him) but also publishing the work of a significant group of composers active in Madrid such as Cabezudo, Durón, Facco, Literes, Navas and Serqueira. The local nature of these loose sheet-music editions is amplified by a piece by Porpora (dated 1733), an Italian cantata with a newly adapted Spanish sacred text.Footnote 73 As might be expected, the transfer from theatre to print of tunes or arias from plays and zarzuelas occurred in a relatively short space of time, exploiting the popularity of a given production. For example, the tonada from Literes's successful Acis y Galatea (first performed at court in December 1708 to mark a royal birthday and later performed as a commercial production) appeared as soon as 1710.

The dissemination of the extant sheet-music prints allows some general observations. First, excluding two locations (Madrid and London) that clearly correspond to the presence of collectors in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the rest may suggest a significant topography of early modern circulation. Spanish cathedrals such as Salamanca and aristocratic households such as that of the Duke of Alba are represented. Manuscript copies of unknown printed sheets from the press which appear in a miscellany of cantatas and songs compiled around 1725 (and related to the Madrilenian monastery of San Martín) hint again at a fluid continuity between manuscript publication and print.Footnote 74 Second, the presence of music sheets in Latin America (Guatemala and Peru, and in the Sánchez Garza Collection in Mexico) needs to be studied separately and is too complex to be developed here. The striking number of sheet prints in Guatemala is clearly related to the existence there of a wider manuscript repertory of cantatas and other sacred music from the Spanish Royal Chapel of the early eighteenth century.

The genres printed as sheet music by Torres are all vocal music in Spanish (the Lamentation of 1704 seems to be an experiment with no further consequences). The pieces are almost all for solo voice and accompaniment, with the addition in some cases of two violins. Following the designation on the front page of each sheet, the known production of the press comprises sixteen cantatas, eight solos or tonadas (strophic songs), four duos for solo voices and four choral pieces for four or eight voices. Fourteen pieces are explicitly labelled as secular (humano): this increases to eighteen (roughly the half of the known output) if one adds the four pieces related to theatre music (plays and zarzuelas). However, these figures can only be indicative, as the fragmentary pieces often do not allow a clear identification and the reconstructed series is obviously incomplete.

As suggested above, the production of printed sheet music shows clear connections to the established networks and transmission patterns of scribal publication. On the other hand, the technological transfer from manuscript to printed sheet did involve some noteworthy differences, as it brought about multiple identical copies of a piece destined for an imagined market of possible buyers. As we have seen, the exchange of manuscript copies as implied by surviving sources such as letters and scores clearly points to a prevalent closed circuit of user exchange and circulation in opposition to open commercial copying. More than one example can be found in these letters where the recipient of a borrador or pliego is requested not to allow the copying in any way of the music that had been sent. The fact that even a scribe known for his commercial disposition such as Lizondo (who nevertheless worked mainly for the Royal Chapel) was frequently paid in kind with live geese and turkeys by a customer like Miguel de Irízar hints at an economy based mainly on close contacts, which is quite different from the entrepreneurial model.Footnote 75 Surely it was on this mode of scribal publication, together with the prospects provided by an amateur market, that the idea of printing sheet music by the Imprenta de Música was at least in part based. On the other hand, surviving Spanish cantata anthologies – like the Mackworth manuscript, made up by an Italian copyist for a Welsh music collector, or a lost manuscript listed in the legacy of Michel-Charles Le Cène in Amsterdam, besides other anthologies found in Portugal and Spain – suggest a wider interest which may have stimulated the idea of printing precisely this genre of music.Footnote 76

The presence of modern genres such as the cantata in the production of sheet music shows clearly that the Imprenta de Música fulfilled the function of making available new music produced by musicians related to the court and the theatres of Madrid. Eloquent testimony to this is found in an observation made in 1726 by Benito Feijoo, one of the most influential intellectuals of the time. In his well-known Discurso sobre la música en los templos (translated into English in London 1778 as Discourse on Church Music) he passes a critical remark on the function of print in relation to musical practice. Speaking about the difficulty of melodic embellishments and vocal coloratura in Italian music and of finding adequate singers in the cathedrals of the different provinces in Spain, he wishes to restrict this style to the select circles of professionals. ‘If you compose in this style’, he says, ‘it should be only for an exceptional performer of one court or another, but it should not be given to the printing press so that it may be scattered around the provinces.’Footnote 77 This remark is very telling: first, because it is clear that it is not aimed at the music press in general, but at Torres's Imprenta de Música and specifically at the modest sheets which were regularly published by the press and which could reach the ‘provinces’; second, because Feijoo, whose Teatro crítico was very influential in Spain, makes clear that this new mode of production was disrupting old patterns of transmission. Three years later, the Diálogo Harmónico sobre el Theatro Crítico – a polemical answer to Feijoo in the form of an enlightened discussion between several fictional characters, and signed by Eustaquio Cerbellón de la Vera (‘músico de la Real Capilla de su Majestad’) – opposed this restrictive view, defending the public musical sphere and the free market. Comments made by the character of Niciato, an ‘hombre maduro y prudente’ (wise older man) who served as organist in the Royal Chapel, and a figure with some notable traits in common with the reputed organist José de Torres, are enlightening. The following passage appears in a discussion in which ancient ecclesiastical music is pitted against modern Italian style, which has inevitably seduced the old Spanish gravity (gravedad española). Print is seen here as an essential aspect of the public sphere where ‘everyone buys at his convenience’ and where the category of the listener embodies the modern enlightened subject, free to communicate and use the diverse commodities offered to him by the market. Niciato is here responding explicitly to the remarks of Feijoo:

Niciato: Lo que más me agrada es aquello de que las tales obras se pongan en la imprenta donde qualquiera las pueda comprar y remitir donde gustase. Lo cual me parece una objeción ridícula porque a ninguno se le precisa que las compre, y además que si eso es delito, prívese al librero el que tenga libros en diversos idiomas y facultades, porque no sirven igualmente a todos. Pero si el proferir semejante proposición se tendría generalmente por disparate, pues cada uno compra lo que le conviene, ¿por dónde será delito en la música (habiendo la misma libertad en el que compra), el que se impriman y vendan de todo género de composiciones? Y lo mismo digo a la objeción de que muchos cantores e instrumentistas que en cosas fáciles parecen bien, descalabran a los oyentes con las difíciles, ¿pues quién le mete en querer volar al que escasamente sabe correr? Cada uno se vista según su estatura, que el vestido no parece mal por ser grande o pequeño, sino por quererse poner el vestido que se hizo para un gigante el que sólo nació para pigmeo.Footnote 78

Niciato: What delights me more is that all these works are printed so that anyone may buy them and send them where he pleases. All this seems to me a ridiculous objection, because nobody is forced to buy them; furthermore, if this is a crime, then the bookseller should be forbidden from having books in different languages and subjects, since they will not be equally useful to everyone. If suggesting such a thing would generally be held as foolish, for everyone buys at his convenience, then how can it be a crime in music (given the same freedom on the part of the purchaser) to print and sell every kind of composition? And I would say the same to the objection that many singers and instrumentalists, who in easy pieces seem good, will give listeners a headache when executing more difficult works, for who forces one to fly when he is barely able to run? Everyone should dress according to his size, for the dress does not look bad because it is big or small, but because one who was born as a pygmy wants to put on a dress made for a giant.

Conclusion: Effects of the Printing Privilege

Torres's defence of his privilege seems to have been very effective during his lifetime. Most of the music prints known to have been produced outside his press involve plainchant tutors that do not use modern music typography and therefore were not protected by the privilege. Martín y Coll's Arte de canto llano is a good example. The first edition was printed in 1714 in Madrid by the widow of Juan García Infanzón. Five years later, the second expanded edition, with a new section on polyphony (canto de órgano), was produced by Bernardo Peralta at the Imprenta de Música, using the modern music types to illustrate this new section. Another example of music print from these years, Nassarre's Escuela música (Zaragoza, 1723–1724), uses only very simple woodcuts for the short music examples. An interesting exception seems to be Santiago de Murcia's Resumen de acompañar la parte con la guitarra, probably published in 1714 in Madrid. At first sight, it could be considered an infringement of Torres's privilege given its guitar tablature engravings. Several aspects of this book are striking. First, we find a short approval signed by Antonio Literes dated 1 August 1717. This may be an error, as the dedication to Jacome Francisco Andriani (Extraordinary Envoy of the Swiss Catholic cantons) is signed 20 August 1714 in accordance with the frontispiece date of 1714.Footnote 79 Secondly, the book may not have passed the censor, since none of the usual legal texts appear, nor is there any reference to a press or a printer. The passing remark in Literes's approval that the engravings were made in Antwerp appears to suggest that the edition was made in such a way as to circumvent Torres's privilege.

Besides this already known evidence, new information related to the Royal Chapel in these highly political years may well point in the same direction. As a result of the disruptions caused by the War of Succession, Torres and Literes were responsible for most of the new music needed in the Royal Chapel between 1709 and 1712 for the main ceremonies such as Christmas, Holy Week or the Forty Hours. As an active supporter of the Habsburg cause, the chapel master Sebastián Durón, formerly responsible for these new compositions (which included sacred songs and cantatas for different forces), was exiled in 1706. During these years Torres and Literes shared the four hundred ducats set aside for this specific service. But suddenly in the spring of 1713 Torres began to claim the whole amount, arguing that he had done all the work the previous year. In an exceptional move, Literes presented a document signed by twelve musicians of the Royal Chapel who certified that during Holy Week in 1712 the Lamentations and the music for the Forty Hours had been composed by Literes himself.Footnote 80 Tensions between the two composers increased as Torres claimed, a few months later, the complete amount for 1712 for providing the music for Christmas, Epiphany, Corpus Christi and Holy Week. This conflict puts the approval signed by Literes for a book which was possibly breaking Torres's privilege in a new light. Even if the fragmentary evidence provided by the chronological series of loose sheets may be invalidated by further findings, it is still striking that the sequence of the known dated sheets shows a regular publication of music by Literes between 1708 and 1710, which appears to be interrupted around the time of the dispute between the two composers until 1717.

The eruption of music printing on the early eighteenth-century Madrid musical scene altered in subtle ways the established modes of composing, performing and hearing. It slowly introduced the new social and material economics produced by printing. On opposing sides, authors like Feijoo or Cerbellón de la Vera were acutely aware of the loss of control which public access in the form of print could offer. As I have observed, print also emphasized public display and gave a new dimension to dedication and patronage. In this sense, the editions of the Imprenta de Música are also representative of a promotional strategy that afforded Torres an exceptional social and professional profile. Torres was not born into a family of musicians, as was often the case in the ancien régime, but came from a literary background. His father was a modest court sheriff (alguacil de corte) and his brother Diego climbed the social ladder to reach the post of judge of the nunciature court and honorary chaplain (capellán de honor) at the Royal Chapel. His elder son, José de Torres Eguiluz, was a lawyer, and appears as translator of a legal text by the Sicilian Giovanni Battista Palermo published by the Imprenta de Música and dedicated by Torres to Queen Isabella de Farnesio.Footnote 81 Dedications such as that for the Missarum liber (possibly emphasizing continuity with former polyphonic mass prints like those of Philippe Rogier or Alonso Lobo)Footnote 82 or Nassarre's Fragmentos created a personal profile constructed through the public exposure made possible by print. The same can be said of Torres's published theoretical writings and his activity as translator. In 1736 he claimed to have translated Brossard's Dictionaire de Musique into Spanish.Footnote 83 Torres's connections with the literary intelligentsia, as displayed in the Introduction to his edition of Coloma's poems, may be crucial for understanding his keen interest in the printing trade, and the transference of the symbolic value of the literary print to music.

It is interesting to compare Torres with the Catalan composer, instrumentalist and poet Jaime de la Tê y Sagau (1684–1736), who settled in Lisbon around 1707. His earlier stay in Madrid for a few years makes it possible that he could have worked at Torres's press. In any case, he was certainly aware of the existence of this press and its exclusive privilege. In Lisbon, de la Tê also founded an ‘Imprenta de Música’ and obtained a printing privilege for ten years in 1715 ‘para poder fazer impremir, e vender muzica como se fazia a la Corte de Madrid e em todas as mais partes da Europa, e que ninguem senao elle podesse ter a da impreçao’.Footnote 84 Contrary to the Spanish press, which did not produce collected editions, Tê published 253 sacred and secular cantatas in a number of volumes, apparently ending his printing activities in 1726 with Emanuele d'Astorga's Cantatas humanas a solo. Unfortunately, no trace seems to remain of the single prints of cantatas that he lists in a printed catalogue.Footnote 85 A different mode of authorial attribution operates in this case: only a proportion of the cantatas are ascribed to de la Tê, the rest appearing anonymously. This contrasts with Torres's approach, in which each sheet edition carefully exhibits the name of the composer.Footnote 86

Epilogue: The end of Typography

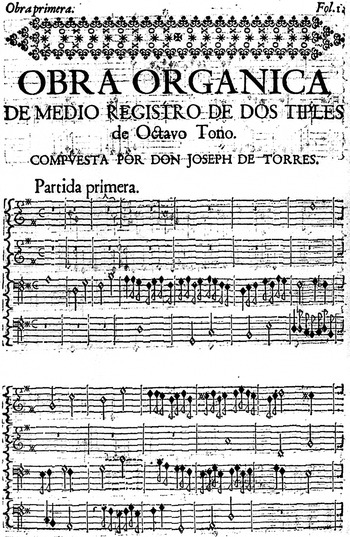

In 1743, five years after Torres's death, José Vicente Hernández Illana asked for a new privilege to found a music press in Madrid. This time it was an engraving shop that was planned: ‘establecer una estampa, a imitación de las de Italia, Francia, Olanda y otros Payses extrangeros’. As proof of his craftsmanship, he supplied two Madrilenian examples: one is an organ piece by José de Torres printed at the old Imprenta de Música using typography and score notation for the four parts of the piece, appearing on eleven vertically oriented pages. The print is undated, and since it is labelled Obra Primera, it was probably conceived as the first of a series (see Figure 6).Footnote 87 The composition is divided into four parts (partidas) in polyphonic style, the last section changing from C to C 6/4 and being labelled Canción.

Figure 6 José de Torres, organ print (Madrid: Imprenta de Música, no date). Madrid, Archivo Histórico Nacional, Consejos 26565-12. Used by permission

The other sample was an elegant new engraving by Hernández Illana of two short pieces by Manuel José Marín, organist at Burgos Cathedral.Footnote 88 The two liturgical pieces elaborate three parts in imitative style on a cantus firmus based on a Vespers hymn: the first piece on Veni creator spiritus and the second on Ave maris stella (see Figure 7).Footnote 89 The earlier print by Torres and the Hernández Illana edition from 1743 are two scores which establish a new chronology for Spanish keyboard prints, filling the chronological gap between Correa de Araujo's Facultad Orgánica (1626) and Sessé's Six Fugues (1773).Footnote 90 Hernández Illana presented this precious organ print by Torres to show the painstaking notation on four independent staves that had to be used in order to print with movable types a complex imitative piece such as this Medio registro para dos tiples.

Figure 7 Manuel José Marín, organ print (Madrid, c1743). Madrid, Archivo Histórico Nacional, Consejos 26565-12. Used by permission

The new privilege was apparently conceded, even if no other prints by him are known. Some time later a Frenchman called Pierre Caillaux, a musician of the Valon Guards of the Spanish Royal Infantry, claimed to the king that he had been working on a similar project for years in Seville; he asked for compensation since the privilege that had been granted to Hernández Illana would not allow him to use his printing tools. He also criticized Illana's punch technique as opposed to his own finer chisel work.Footnote 91 Such initiatives, previously unknown, imply a demand for such prints in eighteenth-century Spain. On the other hand, the scarcity of known production argues against an optimistic view of the market of the time – a market which suffered, as we have seen, under the severe control of censorship and printing privilege.Footnote 92

As mentioned above, Torres had already exaggerated the typographical innovation of combining two or more notes per staff in his 1719 application for a tax exemption for his paper purchases. In the second edition of his Reglas de acompañar (1736) he modestly specifies that this new version appears ‘with the novelty of being printed in the method called intavolatura (as difficult for the press as it is easy for the stamp, or burin) [and] at the cost of my sleep, I have succeeded in executing [this work] in Spain, if not with the greatest beauty, then with sufficient clarity for understanding’.Footnote 93 In a way his melancholic statement about the difficulties of typography in the face of etching and engraving represents a final recognition that the old typographical regime had finally to give way to more flexible technologies. In a telling remark contained in his petition for a new printing privilege signed at the Buen Retiro Palace in Madrid on 25 July 1743, Hernández Illana pointed to the corruption and lack of clarity of print that even forced readers to copy out typographical scores by hand, thus underlining the complementary functions of print and script:

En consideración de [la] perfección que el Maestro Joseph de Torres dió a este establecimiento, se sirvió Vuestra Majestad de concederle demás del mencionado privilegio privativo, la facultad de entrar en esta corte treinta balones de papel de la calidad que eligiere libre de todo impuesto o derecho. Y teniendo observado el suplicante que esta imprenta esta sin … desde la muerte de dicho Don Joseph de Torres, y que los Professores, aficionados a la música desean se restableciese, y si fuesse posible, se llevasse a tal prefección, que no les fuesse necesario hacer copias aun del mismo impreso a lo que se veían precisados por la mucha confusión que ocasionaba la transcripción de las líneas, la separación de las notas, obscura disposición de caracteres, y otros defectos considerables, que no se pueden evitar en una imprenta.

In consideration of the perfection that maestro Joseph de Torres accorded this establishment, Your Majesty decided to grant him, in addition to the exclusive privilege already mentioned, a licence to import into the court thirty balones of quality paper of his choice exempt from any taxes or rights. And the supplicant observes that this press [no longer functions] since the death of the said Don Joseph de Torres and that the experts who are knowledgeable on music wish to re-establish it, and, if possible, to increase this perfection, so that they do not have to copy out the very same print, this made necessary by the great confusion created by the transcription of the staves, separation of the notes, unclear layout of the characters, and other major defects that cannot be avoided in a press.