Introduction

An attic cholesteatoma is commonly encountered in the otology clinic, attributable to a tympanic membrane retraction pocket in the pars flaccida and thus an inward (abnormal) displacement of the tympanic membrane.Reference Yoon, Schachern, Paparella and Aeppli1 Tos and Poulsen clinically divided Shrapnell-type membrane retractions into types 0–IV based on otoscopic findings. Types I and II are mild attic retractions, and types III and IV are severe retractions with deep pockets and bone erosion.Reference Tos and Poulsen2

An attic cholesteatoma typically presents as a widening of the pars flaccida, usually accompanied by granulation, otorrhoea, or debris accumulation and bone destruction that are evident during the clinical course. Recently, attic cholesteatomas featuring tiny retractions, or closure, of the pars flaccida but lacking any granulation tissue or debris have been reported.Reference Matsuzawa, Iino, Yamamoto, Hasegawa, Hara and Shinnabe3–Reference Kim, Jung, Sung, Kim and Kim5 An attic cholesteatoma may be present even when the retraction is not severe. Matsuzawa et al.Reference Matsuzawa, Iino, Yamamoto, Hasegawa, Hara and Shinnabe3 described three patients with attic cholesteatomas but otoscopically normal pars flaccida lesions immediately before surgery and speculated that pars flaccida closure was attributable to lesion healing after inflammation had resolved. Attic retractions must be closely followed up either endoscopically or microscopically; if a cholesteatoma is suspected, temporal bone computed tomography (CT) is required. Few studies have reported the granulation pathologies of middle ears with pars flaccida retraction pockets. This is the topic of our study here.

Materials and methods

The clinical records of patients who underwent tympanomastoidectomy to treat middle-ear or mastoid granulation pathologies in our tertiary care referral centre between January 2012 and January 2019 were retrospectively reviewed.

The inclusion criteria were: age of 18 years or older; an intact tympanic membrane with no history of perforation, otorrhoea, effusion, trauma or previous ear surgery; retraction of the pars flaccida; CT evidence of locally dense soft tissue lacking bony erosion in the middle ear or mastoid; and intra-operative and histological confirmation of a granulation pathology but no evidence of a cholesteatoma. The exclusion criteria were: age of less than 18 years; endoscopic evidence of a tympanic membrane perforation or otorrhoea; previous ear surgery or paracentesis; middle-ear effusion; and histological evidence of a cholesteatoma.

Medical reports were analysed for demographic data, presenting symptoms, endoscopic features, disease location and extension, surgical technique, and outcomes. Clinical and operative findings and treatment outcomes were analysed. Endoscopy and temporal bone CT were performed 12 months after operation. The average hearing thresholds at 0.5, 1, 2 and 3 kHz pre-operatively and 12 months post-operatively were audiometrically determined.

Surgical procedure

All patients were placed under general anaesthesia. Of the 59 patients, 52 underwent canal wall up mastoidectomy with posterior tympanum to explore the ossicular chain and eliminate granulation tissue; the normal mucosa was preserved. Granulation tissue was removed via endoscopic endaural atticoantrotomy in seven patients. Neither the mastoid cavity nor the external auditory canal were packed. Surgical specimens were sent for histological examination. All patients were followed up for 12 months.

Results

The records of 59 patients (31 males and 28 females; average age: 41.5 ± 3.6 years; range: 29–61 years) were included. The right ear was affected in 36 patients and the left ear was affected in 23 patients. No patient had a history of otorrhoea, tympanic membrane perforation, prior ear surgery, middle-ear effusion or paracentesis.

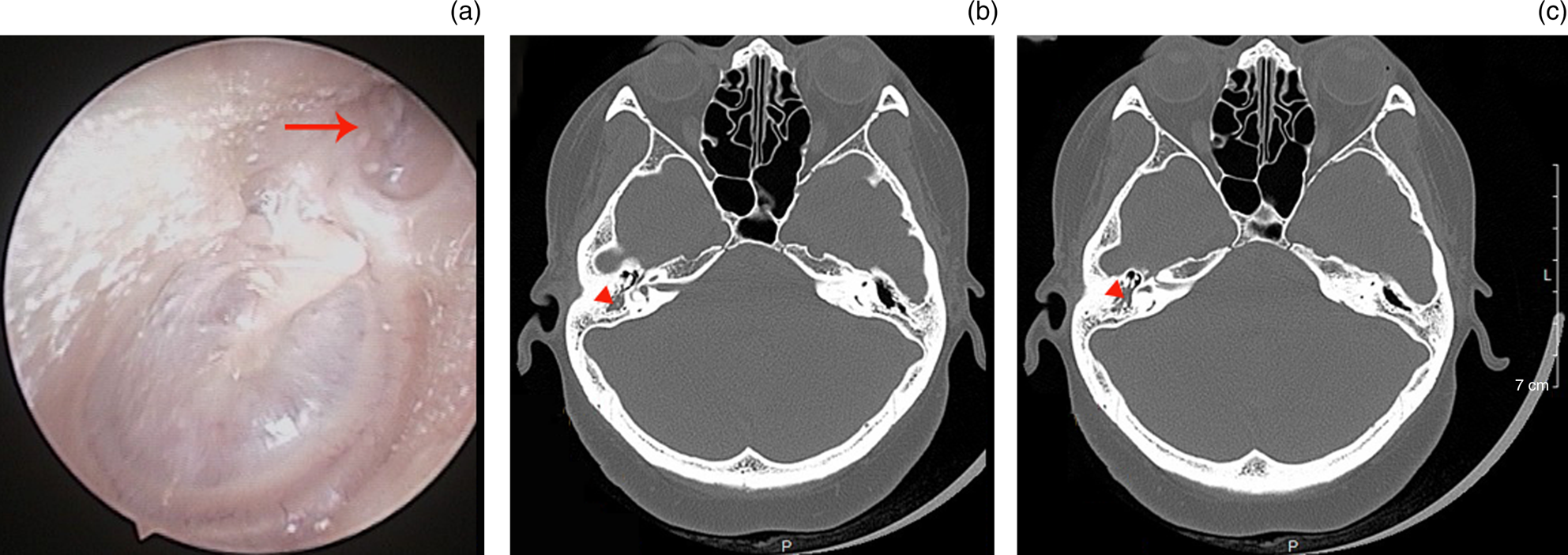

In all patients, endoscopic examination showed a normal pars tensa with retraction of the pars flaccida but no evidence of an atrophic tympanic membrane or myringosclerosis. The pars flaccida retraction pockets lacked granulation tissue and debris. Type II attic retraction was apparent in 44 patients, and type III retraction was apparent in 15 patients, as defined by Tos and Poulsen (Figure 1). Low-pitched tinnitus was the principal complaint of all 59 patients (100 per cent). Fourteen patients (23.7 per cent) also complained of ear fullness, but none complained of hearing loss. The duration of symptoms ranged from four months to six years.

Fig. 1. A 57-year-old female. (a) Endoscopic examination showed a right intact tympanic membrane with type II retraction of the pars flaccida. The red arrow shows pars flaccida retraction. (b and c) Axial plane computed tomography scans showed dense soft tissue in the aditus ad antrum. The red arrowheads show the granulation pathology. L = left; P = posterior

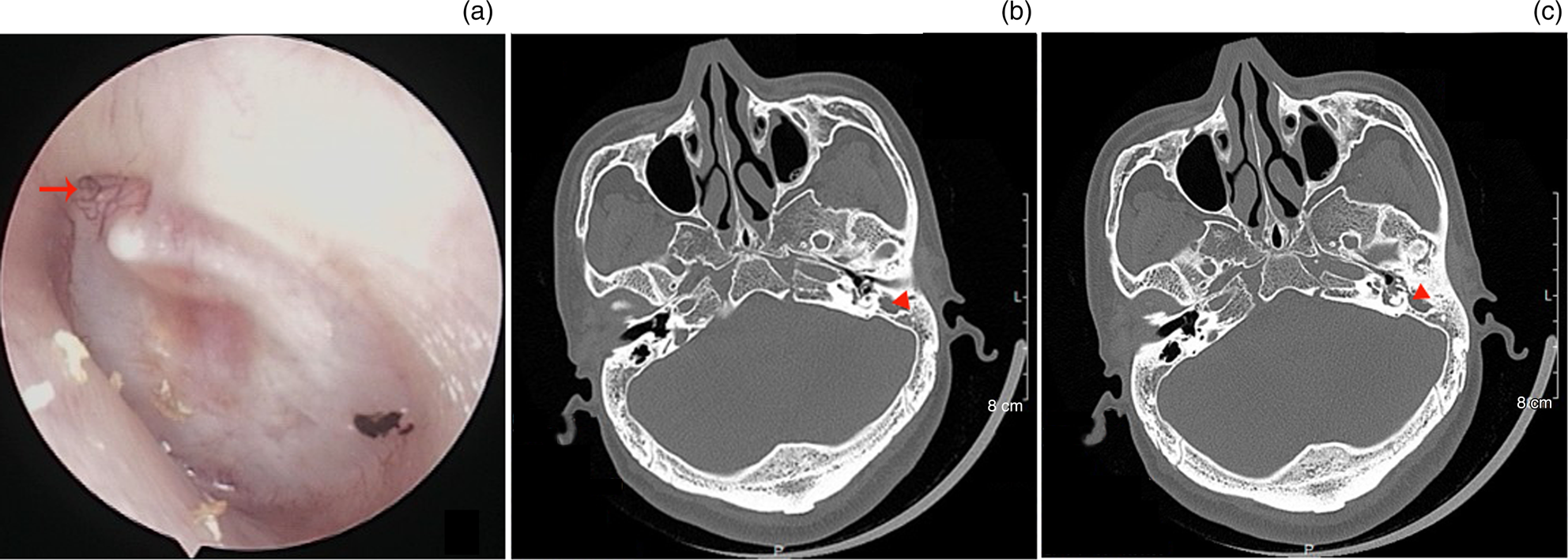

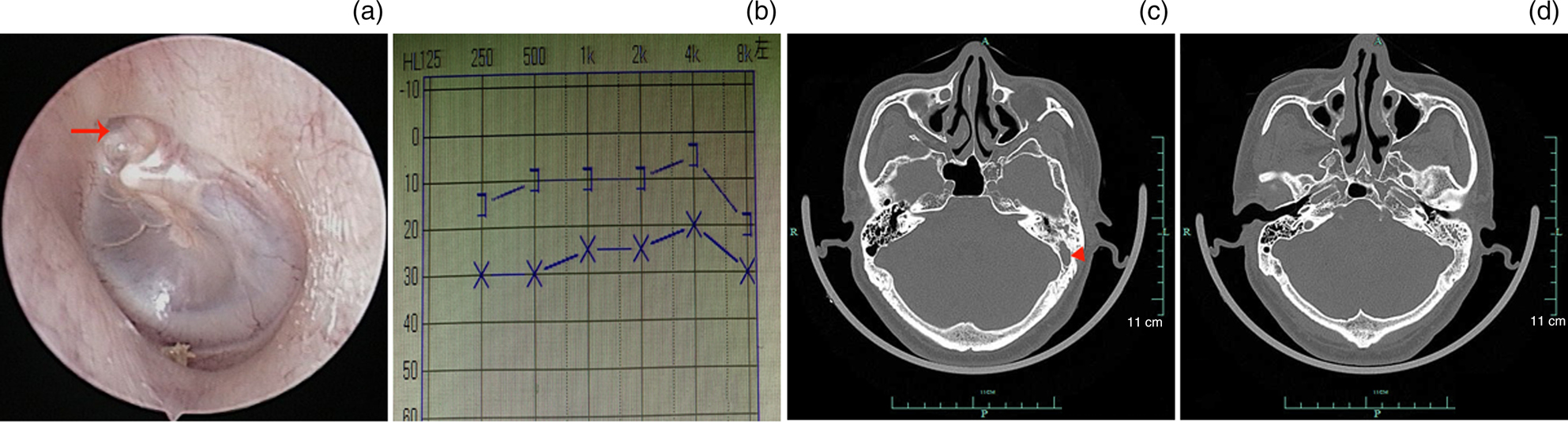

Temporal bone CT showed dense soft tissue lesions lacking bony erosions in the Prussak space of 17 patients (28.8 per cent), in the aditus ad antrum of 27 patients (45.8 per cent; Figure 1), in the attic and antrum of 13 patients (22.0 per cent; Figure 2) and in the mastoid of 2 patients (3.4 per cent; Figure 3). Of the 59 patients, canal wall up mastoidectomy with posterior tympanum was performed in 52 patients (88.1 per cent) and endoscopic endaural atticoantrotomy was performed in 7 patients (11.9 per cent). No ossicular chain destruction was evident. The presence of granulation tissue was confirmed by both exploratory surgery and histological examination; cholesteatomas were excluded in all patients.

Fig. 2. A 31-year-old male. (a) Endoscopic examination showed a left intact tympanic membrane with type II retraction of the pars flaccida. The red arrow shows pars flaccida retraction. (b and c) Axial plane computed tomography scans showed dense soft tissue in the attic, aditus ad antrum and antrum. The red arrowheads show the granulation pathology. L = left; P = posterior

Fig. 3. A 48-year-old male. (a) Endoscopic examination showed a left intact tympanic membrane with type II retraction of the pars flaccida. The red arrow shows pars flaccida retraction. (b) The mean air–bone gap was 15 dB. (c and d) Axial plane computed tomography scans showed dense soft tissue in the mastoid. The red arrows indicate the retraction of the pars flaccida. The red arrowheads show the granulation pathology. R = right; L = left; P = posterior

All patients were followed up for 12 months. The mean air–bone gap was 14.7 ± 2.3 dB peri-operatively and 12.8 ± 5.7 dB post-operatively (p > 0.05, Wilcoxon signed-rank test). Tinnitus disappeared completely in 48 patients (81.4 per cent), improved significantly in 9 patients (15.3 per cent) and improved mildly in 2 patients (3.3 per cent). No complication (iatrogenic sensorineural hearing loss, facial nerve palsy, or vertigo) was observed during the follow-up period.

Discussion

It is well known that irreversible middle-ear or mastoid pathology can develop behind an intact tympanic membrane.Reference da Costa, Paparella, Schachern, Yoon and Kimberley6,Reference Jaisinghani, Paparella, Schachern and Le7 Acquired middle-ear cholesteatomas behind intact tympanic membranes have received increasing attention because the principal complaint is hearing loss.Reference Matsuzawa, Iino, Yamamoto, Hasegawa, Hara and Shinnabe3,Reference Lee, Hong, Kim, Park and Baek4,Reference Di Lella, Bacciu, Pasanisi, Ruberto, D'Angelo and Vincenti8,Reference Mills9

Some studies on human temporal bones have found that granulation tissue is the most common form of middle-ear pathology behind an intact tympanic membrane.Reference da Costa, Paparella, Schachern, Yoon and Kimberley6,Reference Jaisinghani, Paparella, Schachern and Le7 da Costa et al.Reference da Costa, Paparella, Schachern, Yoon and Kimberley6 observed that various extents of granulation tissue were the most prominent pathological features of 96 per cent of temporal bones with tympanic membrane perforations and 97 per cent of bones without such perforations. Paparella et al.Reference Paparella, Schachern and Cureoglu10 found that over 80 per cent of patients lacked tympanic membrane perforations when a total of 155 temporal bones were associated with chronic otitis media. However, most cases may be asymptomatic or exhibit only minor symptoms. A granulation pathology may grow slowly over many years, to be detected only when symptoms appear. Meyerhoff et al.Reference Meyerhoff, Kim and Paparella11 reported that only 24 of 36 ears with granulation tissue and an intact tympanic membrane exhibited otological symptoms.

In the present study, all tympanic membranes exhibited pars flaccida retraction. Granulation and retraction pathologies may be closely associated with Eustachian tube dysfunction and negative pressure within the middle ear. Chronic Eustachian tube dysfunction causes negative pressure within, and ventilation abnormalities of, the middle ear, gradually inducing retraction associated with two pathological changes,Reference Yoon, Schachern, Paparella and Aeppli1 one of which is persistent inflammation of the middle-ear mucosa (which may trigger epithelial invagination) and the other which is acquired cholesteatoma.

Some authors have reported attic cholesteatomas associated with tiny pars flaccida retractions.Reference Matsuzawa, Iino, Yamamoto, Hasegawa, Hara and Shinnabe3–Reference Kim, Jung, Sung, Kim and Kim5 Negative pressure within the middle ear may trigger oedema and granulation tissue proliferation. If the latter tissue is quiescent during the development of the Eustachian tube, no cholesteatoma develops. The granulation pathology may grow silently over many years, becoming very large at the time of detection.Reference Di Lella, Bacciu, Pasanisi, Ruberto, D'Angelo and Vincenti8 Surgical exploration and CT confirmed that the granulation pathologies of our patients were confined principally to the Prussak space and aditus ad antrum. Kim et al.Reference Kim, Jung, Sung, Kim and Kim5 examined temporal bone CT scans of patients with tinnitus and intact tympanic membranes and found dense soft tissue lesions within the Prussak spaces of 12.3 per cent such patients (18 of 146). Another study found that the aditus ad antrum was obstructed by granulation tissue in 75 per cent of patients.Reference Alleva, Paparella, Morris and da Costa12 The granulation pathology was confined to the mastoid in only two patients of our present study. A previous work suggested that out of the protympanum, mesotympanum, isthmus, attic, aditus ad antrum and isolated groups of mastoid air cells, any or all of these may become narrowed or obstructed.Reference Alleva, Paparella, Morris and da Costa12,Reference Schachern, Paparella, Sano, Lamey and Guo13

Low-pitched tinnitus was the chief complaint of our patients (100.0 per cent), followed by ear fullness (23.7 per cent); no patient complained of significant hearing loss. The pre-operative mean air–bone gap was 14.7 ± 2.3 dB. These findings differ from those in patients with cholesteatomas behind intact tympanic membranes; the chief complaint is hearing loss.Reference Matsuzawa, Iino, Yamamoto, Hasegawa, Hara and Shinnabe3–Reference Kim, Jung, Sung, Kim and Kim5 This may reflect the extent of the lesion. Previous studies have suggested that a cholesteatoma behind an intact tympanic membrane may damage the ossicular chain. However, we found no such damage. The tinnitus disappeared completely or improved significantly in 96.7 per cent of our patients after surgery.

We speculate that the presence of middle-ear granulation tissue may correlate with tinnitus. However, the mechanism remains unclear. Ventilation and drainage path obstructions may be important. Obstructions may trigger anatomical malformation of, or variations in, the middle ear or mastoid.Reference Paparella, Schachern and Cureoglu10 Although some such blockages do not affect hearing, persistent obstruction triggers effusion, release of inflammatory mediators, and local pathological changes (scarring and mucosal fibrosis), thereby inducing tinnitus. In addition, local obstructions may change the middle-ear airflow direction or reduce the diameter of the airflow passage, triggering tinnitus. The mechanism is similar to that of snoring caused by upper airway obstruction. Also, certain granulation pathologies may obstruct or stimulate the round window niche. Vambutas and PaparellaReference Vambutas and Paparella14 reported that granulation tissue was most frequently (76 per cent) located in the epitympanum and round window niche, involving the mastoid antrum in only 52 per cent and the mastoid bone in 61 per cent of cases. Hidden inflammation or a bacterial infection damaged the inner ear via the round window. Some authors have suggested that tinnitus reflects inappropriate interactions of the middle and inner ear that are often unrecognised because the symptoms of labyrinthine disease may be non-specific.Reference Vambutas and Paparella14

• Pars flaccida retraction is linked to an attic cholesteatoma in most cases. However, such retraction may also reflect a granulation pathology of the middle ear or mastoid

• Persistent low-pitched tinnitus was the principal complaint of patients with middle-ear granulation pathologies

• Middle-ear granulation pathologies should be considered when examining patients with low-pitched tinnitus

• Computed tomography (CT) and surgical exploration are required. CT usually shows local, dense soft tissue without bony erosion

• Although the tinnitus mechanism remains unclear, ventilation and drainage path obstructions in the middle ear or mastoid may be in play

Although CT often underestimates the extent of disease, CT showed local dense soft tissue without bony erosion in the present study, and a granulation pathology was surgically confirmed in all patients. We performed canal wall up mastoidectomy on 88.1 per cent of our patients and endoscopic endaural atticoantrotomy on 11.9 per cent of patients. The latter procedure is appropriate for patients with attic pathologies, but mastoidectomy remains the principal procedure. No complication (iatrogenic sensorineural hearing loss, facial nerve palsy or vertigo) was observed during the follow-up period.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Science and Technology Agency of Yiwu city, China (grant number: 2018-3-76).

Competing interests

None declared