Background

Polygamy is generally defined as a marital relationship involving multiple spouses. The different types of polygamy include polygyny, ‘the voluntary union of one man to multiple wives’, polyandry, the marriage of one woman to multiple men, and polygynandry, the union of multiple husbands to multiple wives (Al-Krenawi, Reference Al-Krenawi2001; Elbedour et al. Reference Elbedour, Onwuegbuzie, Caridine and Abu-Saad2002). The most common form of polygamy worldwide is polygyny or the plurality of wives (Valsiner, Reference Valsiner and Valsiner1989); as such, it is more commonly referred to as polygamy, including in academic literature and the remainder of this paper. While the worldwide prevalence of polygamy is unknown, its existence has been documented ‘in 80% of societies across the globe, including the United States’ (Hassouneh-Phillips, Reference Hassouneh-Phillips2001). Polygamy is practiced in over 850 societies, mostly in Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, Asia and Oceania, with anywhere from 20% to 50% of all wives participating in polygamous marriages in some cultures (Bergstrom, Reference Bergstrom1994; Elbedour et al. Reference Elbedour, Onwuegbuzie, Caridine and Abu-Saad2002). Indeed, some indeterminate millions of people the world over participate in polygamy though accurate and current statistics of its estimated prevalence are not yet available (Slonim-Nevo & Al-Krenawi, Reference Slonim-Nevo and Al-Krenawi2006).

The reasons for polygamy can be many, varied and multi-faceted across and within cultures. These reasons can extend from some sects of Islamic faith, traditional practices, cultural perceptions of family and agricultural and population needs (Al-Krenawi, Reference Al-Krenawi1998; Al-Krenawi & Graham, Reference Al-Krenawi and Graham1999b; Elbedour et al. Reference Elbedour, Onwuegbuzie, Caridine and Abu-Saad2002; Slonim-Nevo & Al-Krenawi, Reference Slonim-Nevo and Al-Krenawi2006). Still, opinions regarding the practice of polygamy within practicing cultures frequently vary within societies and families, across age groups and gender, even among and within those who practice it (Chaleby, Reference Chaleby1988; Al-Krenawi et al. Reference Al-Krenawi, Graham and Ben-Shimol-Jacobsen2006). Furthermore, perspectives of polygamy have been documented as varying even within respondents themselves (Al-Krenawi et al. Reference Al-Krenawi, Graham and Izzeldin2001; Shepard et al. Reference Shepard, Panos and Thompson2010).

As a consequence of the sheer magnitude of the polygamous population as well as the breadth of the research topic, polygamy has substantially developed as a subject of study over the last three decades. Of course, the criticism uttered by Welch & Glick (Reference Welch and Glick1981) still stands partially true – namely that the study of polygamy is largely ignored by researchers despite the fact that its ongoing practice warrants its further study. Indeed, Al-Krenawi (Reference Al-Krenawi1999) has further argued that, ‘researchers and family practitioners have rarely paid attention to the association between polygamy and mental health’ though some published evidence has suggested that polygamous women and children report higher rates of emotional distress, psychological problems, familial conflict, jealousy and stress than their monogamous counterparts (Al-Krenawi, Reference Al-Krenawi1998; Elbedour et al. Reference Elbedour, Onwuegbuzie, Caridine and Abu-Saad2002).

Considering the possible vulnerability of these sub-populations, the growing body of published evidence investigating the impact of polygamy on women's mental health, and the subsequent need for research synthesis and appraisal, an exhaustive literature search and a systematic review appears requisite. Thus, in compliance with the concepts of evidence-based research to make better use of what evidence already exists (Chalmers, Reference Chalmers2003; Sherman, Reference Sherman2003), this paper adds such a systematic review to the existing discourse on mental-health implications for polygamous women.

Objective

This paper is directed towards the systematic illumination of the following research question: Among women in polygamous marriages, as compared to women in monogamous marriages in the same population, what is the prevalence of mental-health issues?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for review

The selected studies are concerned with identifying the prevalence of mental-health issues in polygamous v. monogamous wives. As the extent of relative or replicated research on polygamy is yet limited and as the current paper constitutes a systematic review without a meta-analysis, all study types, non-western nations, settings, cultures, mental-health outcomes, measurement tools and statistical analyses published and accessible in English are considered. These sensitive inclusion criteria are designed to identify as many studies relevant to the prevalence of mental-health issues among polygamous v. monogamous women as possible. Research conducted among polygamous women in western nations or among specified female populations (e.g., infertile, postpartum, ill, widowed, immigrant, etc.), however, is excluded due to the hypothesized additional confounding legal or mental-health implications. The broad mental-health outcomes are enjoined as a means to identify all currently measured outcomes and potential risk factors. Finally, the requirement for a monogamous comparison group is elected as national statistics and prevalence rates on polygamy and mental health are often unavailable in developing nations; thus, the internal provision of a comparison group ensures more accurate interpretation of the cross-sectional findings.

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group's search phrase was employed and PsycInfo (1967 to November 2011) and Medline (1985 to November 2011) were searched 2 November 2011 and 14 November 2011, respectively (see Table 1). The references and bibliographies of all topical and selected articles were systematically hand-searched to identify other relevant studies. The leading expert in the field, Alean Al-Krenawi, was contacted for an exhaustive listing of his work and information regarding published and unpublished trials. Other literature outside of the main journal literature was searched where possible, using general search engines.

Table 1. Search string for the impact of polygamy on women's mental health

Methods of the review

All titles and potentially relevant abstracts were screened as retrieved by the database searches and personal communication. All topical and selected article bibliographies were subsequently and systematically searched following the same procedure. Further, the bibliographies of those resulting article selections were likewise hand-searched, continuing this process until saturation was reached. The inclusion criteria were then applied to determine which studies were eligible for the review.

The study details and findings were extracted on a case-by-case basis using a simplified extraction form. Information on the study population and comparison, sampling method and size, measurement tools, statistical analyses and findings were recorded. Finally, the included studies were methodologically reviewed in terms of internal validity, study power and external validity.

Results

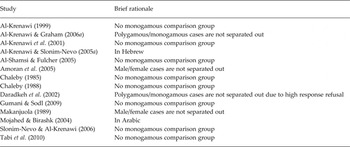

Of the 795 article titles identified by PsycInfo, 17 were identified as potentially relevant. Of the 430 article titles returned by Medline, 10 were selected for further review, with an overlap of 8 relevant titles between the two databases. An approximate 75 potentially relevant titles and abstracts were further identified through bibliographic, personal communication and gray literature searches. Of all noted research articles, 22 met selection criteria. The most common reason for exclusion was the omission of a socio-demographic variable for polygamy. However, 14 studies were excluded from detailed review as their publication language or sample comparison group failed to meet the previously specified inclusion criteria (see Table 2). Five additional studies that potentially met selection criteria were identified, but were inaccessible or unattainable and, therefore, omitted from the present review (Ebigbo et al. Reference Ebigbo, Onyeama, Ihezue and Ahanotu1981; Mojahed & Birashk, Reference Mojahed and Birashk1995; Al-Krenawi & Slonim-Nevo, Reference Al-Krenawi and Slonim-Nevo2003; Al-Krenawi & Graham, Reference Al-Krenawi and Graham2004; Iben-Hammad et al. Reference Iben-Hammad, Galai, Shoham-Vardi and Weitzman2004).

Table 2. Brief rationale for excluded studies

Description of included studies

As previously mentioned, 22 cross-sectional studies were selected for inclusion in this review. These studies address the prevalence of mental-health issues in polygamous v. monogamous women from varying cultures around the world. One study was set in Australia and five other studies were set in Africa, including Uganda, Cameroon, Malawi, Nigeria and Tanzania. The remaining 16 studies were set in the Middle East – in Israel (constituting four of the studies), the United Arab Emirates (three studies), Kuwait (two studies), Jordan (two studies), Iran, Pakistan, Palestine, Syria and Turkey. In total, some 1913 polygamous women and 3326 monogamous women are represented across the study samples, though exact subgroup numbers are not completely known for three of the included studies (Mumford et al. Reference Mumford, Nazir, Jilani and Baig1996; Abou-Saleh et al. Reference Abou-Saleh, Ghubash and Daradkeh2001; Hinks & Davies, Reference Hinks and Davies2008). A variety of mental-health outcome measurement tools are represented across the studies as presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Mental-health outcome measurement tools by study

The results of four studies (set in the United Arab Emirates, Pakistan and Tanzania) suggest no significant difference in the prevalence of psychiatric disorder, depression, somatic symptoms or anxiety in polygamous women as opposed to monogamous women (Mumford et al. Reference Mumford, Nazir, Jilani and Baig1996; Abou-Saleh et al. Reference Abou-Saleh, Ghubash and Daradkeh2001; Hamdan et al. Reference Hamdan, Hawamdeh and Hussein2008; Patil & Hadley, Reference Patil and Hadley2008). Three studies (set in Cameroon, Malawi and Turkey) report mixed findings, including marginal differences in life and marital satisfaction, subjective well-being, and depressive and conversion disorders, but significantly less marital satisfaction in younger senior wives, low well-being for polygamous women following Malawian traditional beliefs and significantly high somatoform dissociation among senior wives (Gwanfogbe et al. Reference Gwanfogbe, Schumm, Smith and Furrow1997; Ozkan et al. Reference Ozkan, Altindag, Oto and Sentunali2006; Hinks & Davies, Reference Hinks and Davies2008). Finally, the remaining 15 studies ultimately conclude significantly higher prevalence of mental-health issues in polygamous women, including a higher prevalence of somatization, anxiety, hostility, psychoticism and psychiatric disorder as well as reduced life satisfaction, problematic family functioning, marital dissatisfaction and low self-esteem (SE). The exploration of the methodological quality, overall findings and implications for practice and future research follows. Due to the wide variation across countries, cultures, beliefs, study populations and research tools, the following analysis does not include a meta-analysis.

Methodological quality of included studies

Ten of the 22 studies are of lower priority as their measurement of prevalence involves correlational analyses of multiple different socio-demographic variables (i.e., the analysis between polygamy and mental health was not the primary objective). The remaining 12 studies, however, afford greater attention and critical appraisal. Tables 4 and 5 contain a brief summary of the methods and findings of each of the included studies.

Table 4. A brief summary of included study characteristics

Table 5. A brief summary of included study findings

Ten included studies comprise correlational studies or socio-demographic analyses, indicating mixed results as to the prevalence of mental-health problems in polygamous women as compared to monogamous women. Of these, Abbo et al. (Reference Abbo, Ekblad, Waako, Muhwezi, Musisi and Okello2008), Daradkeh et al. (Reference Daradkeh, Alawan, Al Ma'aitah and Otoom2006), Ghubash et al. (Reference Ghubash, Hamdi and Bebbington1992), Leighton et al. (Reference Leighton, Lembo, Hughes, Leighton, Murphy and Macklin1963) and Maziak et al. (Reference Maziak, Taghrid, Fawaz, Fouad and Nael2002) report that polygamy is a significant determinant of psychological distress in married women (psychological distress (SRQ-20 score ≥6): OR(95% CI 1.38–10.98) = 3.62, p = 0.012; psychiatric symptoms (Present State Examination (PSE)): t(178) = 2.04, p = 0.04; psychological distress (SRQ-20 score ≥ 8): OR(95% CI 1.1–12.0) = 3.3, p = 0.03). Whereas Abou-Saleh et al. (Reference Abou-Saleh, Ghubash and Daradkeh2001), Gwanfogbe et al. (Reference Gwanfogbe, Schumm, Smith and Furrow1997), Hamdan et al. (Reference Hamdan, Hawamdeh and Hussein2008), Hinks & Davies (Reference Hinks and Davies2008) and Mumford et al. (Reference Mumford, Nazir, Jilani and Baig1996) report mixed results, indicating significantly less marital satisfaction in younger senior wives, low well-being for polygamous women following Malawian traditional beliefs and significantly high somatoform dissociation among senior wives, but non-significant associations between monogamous and polygamous women for lifetime prevalence rates of ICD-10 psychiatric disorders, life and marital satisfaction, Beck Depression Inventory scores and Bradford Somatic Inventory scores. However, the methodological quality of these correlational studies is considerably limited by their general and secondary search for significant associations between mental-health outcomes and a variety of socio-demographic factors, not to mention their frequent reliance on quasi- and non-random sampling techniques and small or unreported polygamous subsamples (N range = 224–2000, with polygamous subsamples reportedly ranging from 11 to 544).

Al-Krenawi (Reference Al-Krenawi2001) is a lower-quality cross-sectional, prevalence study of mental-health issues in polygamous women compared to monogamous women in Israel. The sample is decently sized (N = 92) and controlled in terms of diagnosis and exposure. However, the significant results must also be interpreted and applied with caution as the study sample and outcome measurements are flawed (self-esteem (open-ended questionnaire): χ2(1) = 28.11, p < 0.001; loneliness (open-ended questionnaire): χ2(1) = 26.36, p < 0.001). The sample is a convenience sample comprised only of out-patients referred by general practitioners, the polygamous women are senior wives of two-wife families only (N = 53), and the measurement tools are largely non-validated and subjective. Finally, the incomplete and selective reporting of statistical results and the lack of statistical control are also highlighted as significant limitations.

Al-Krenawi (Reference Al-Krenawi2004) is a high-quality cross-sectional study comparing monogamous and polygamous, Bedouin-Arab women's mental health across a number of reliable and well-validated measures (family functioning (Family Assessment Device (FAD)): F(2, 1364) = 59.58, p < 0.001; marital relationship (ENRICH): F(2, 1364) = 76.68, p < 0.001; mental health (General Severity Index (GSI)): F(2, 1364) = 57.81, p < 0.001; life satisfaction (SWLS): F(2, 1364) = 30.62, p < 0.001). Study characteristics of particular virtue include its relatively strong and representative sample – both in size (N = 376) and random and clustered recruitment methods – its employment of well-validated and replicated measurement tools, and its selection of rigorous statistical analyses and controls. A weakness of the study, however, is that the recruitment strategy for participants may only represent those listed on the municipality registers.

Al-Krenawi (Reference Al-Krenawi2010) is a mediocre quality cross-sectional study. Although the sample is quite large (N = 309), its external validity is flawed by its use of a convenience sample and restriction to polygamous, senior wives. Very little information is provided about the recruitment and selection process and similar limitations in reporting are unfortunately apparent in other sections of the study, including some undefined socio-demographic classifications, an unexplained discrepancy in coding the ENRICH questionnaire, an under-detailed results section, and a discussion that incorrectly references other study findings and draws conclusions beyond the parameters of the present study. Nevertheless, Al-Krenawi (Reference Al-Krenawi2010) represents the first and only research of the impact of polygamy on married women's mental health in Palestine. It also reports findings on a new variable of interest – the disagreeability of polygamous marriages according to polygamous women (80.2%) and monogamous women (97.4%). Finally, the study employs well-validated and replicated measurement tools as well as rigorous statistical analyses and controls (family functioning (FAD): t(308) = 4.56, p < 0.001; marital satisfaction (ENRICH): t(308) = 5.89, p < 0.001; self-esteem: t(308) = 2.89, p < 0.01; life satisfaction (SWLS): t(308) = 3.53, p < 0.01; mental health (GSI), t(308) = 3,79, p < 0.01).

Al-Krenawi & Graham (Reference Al-Krenawi and Graham2006b) represent a strong, well-designed cross-sectional study, including a larger, more representative sample (N = 352). The significant sample size, the proportionate random sampling of women from seven recognized villages, and the cluster sampling of women from nine unrecognized villages, lends additional power to the research findings. Furthermore, the methods of measurement are of high quality with indications that the interviewers were trained and the tools of measurement validated and back-translated for reliability. The primary weaknesses of the study design and research methods are considerably fewer: the selection criteria for participants potentially represents only those listed on the municipality registers, there is an unexplained discrepancy in coding of the ENRICH questionnaire, and the relationship between marital status and mental distress is not statistically controlled for by other potentially contributing factors (family functioning (FAD): F(2, 350) = 41.14, p < 0.001; marital relationship (ENRICH): F(2, 350) = 50.36, p < 0.001; mental health Bradford Somatic Inventory (BSI): F(2, 350) range = 23.2–44.02, p < 0.001; life satisfaction (SWLS): F(2, 350) = 19.89, p < 0.001).

Al-Krenawi et al. (Reference Al-Krenawi, Graham and Gharaibeh2011) is a relatively strong, cross-sectional study comparing the psychological well-being of monogamous and polygamous women. The sample size is decent (N = 199) though similarly limited by convenience recruitment and its selection of senior wives of two-wife families. Strengths of note, however, include its additional consideration of two new variables (consanguinity and agreeability with polygamous unions), its employment of well validated and replicated measurement tools, and its use of rigorous statistical and multivariate analyses. It was found that 66.2% of senior wives and 87.5% of monogamous wives reported disagreeing with polygamous marriages and that first wives experienced significantly more distress (family functioning (FAD): t(198) = 3.95, p < 0.001; self-esteem: t(198) = 2.53, p < 0.01; life satisfaction (SWLS): t(198) = 3.29, p < 0.01; mental health (GSI): t(198) = 3.19, p < 0.01). However, a few study limitations include its failure to report the number of individuals who refused or withdrew participation and its discrepant coding of the ENRICH questionnaire.

Al-Krenawi & Slonim-Nevo (Reference Al-Krenawi and Slonim-Nevo2008) is an example for future replication. Again, the large sample (N = 315) and its attempt for random selection are assets of its design. The study also minimizes bias by specifying criteria for exposure to polygamy and by using strong, validated, back-translated and specific measurement tools (mental health (BSI): t(313) range = 0.77–2.22, p range = less than 0.001 to non-significant; self-esteem (SE): t(313) = −3.6, p < 0.001; family functioning (FAD): t(313) = 6.28, p < 0.001; marital satisfaction (ENRICH): t(313) = 8.55, p < 0.001). Finally, the study employs strong statistical analyses, namely linear regression, to identify other predictive variables of poor mental-health outcomes (family functioning (FAD) and psychological symptoms (BSI): F(2, 313) range = −0.45–0.49, p < 0.001; polygamous/monogamous and obsession–compulsion: F(2, 313) = 0.11, p < 0.05; polygamous/monogamous and psychotism: F(2, 313) = 0.12, p < 0.05). The associated weaknesses, however, are primarily associated with the sample. Although randomized, the sample may not prove representative provided that those included were available by phone, came from two-wife families, and had a child fulfilling the inclusion criteria of a concurrent study.

Al-Sherbiny (Reference Al-Sherbiny2005) is a lower-quality cross-sectional, prevalence study. Although the sample size is decent (N = 100), the weaknesses of the study are considerable: the research methods are vague and non-descriptive, prohibiting replication; the generalizability of the findings is restricted to first wives only; and most importantly, it is uncertain as to whether the participant groups were wholly comparable as they were recruited differently – snowball sampling for polygamous women as referred by social workers and psychologists and random sampling for monogamous women. Consequently, the two groups varied significantly in age, education, family size, etc., making it unsurprising that the control group reported fewer psychiatric, emotional and physical complaints (symptoms (General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) total score ≥8): χ2(1) = 16.32, p < 0.001). Furthermore, the monogamous participants did not receive a psychiatric interview.

Chaleby (Reference Chaleby1987) is a low-quality, cross-sectional retrospective study of the prevalence of psychiatric disorder in monogamous v. polygamous wives as derived from a random sample of out-patient charts. Although the sample is decently sized (N = 126), it is unfortunately flawed; the total population of out-patient charts is not reported, the process of random selection is not described, the number of excluded charts is not provided, and the sample is limited to married, never-hospitalized, out-patient women with complete and comprehensive charts. Furthermore, the results are subjective as no criteria were specified for the classification of psychiatric disorders and as sample proportions of psychiatric disorder by type of marriage were compared to outdated 1975 census and 1980–1981 court marriage records for significance. Finally, while a significant interaction was found among the variables for marriage type and psychiatric disorder (χ2(3) = 13.79, p < 0.01), no further analysis or explanation was provided to describe the relationship, though study conclusions identify senior wives as ‘far more susceptible’ and describe a ‘particularly high incidence of somatoform disorders’.

Eastwell (Reference Eastwell1974) is a low-quality cross-sectional study of the prevalence of psychiatric disorder in monogamous wives v. polygamous wives among the Murngin in North Australia. The sample is small (N = 33) and limited to psychiatric cases, with small monogamous (N = 4) and polygamous (N = 21) subgroups. Furthermore, the methods are under-detailed, the criteria for determining psychiatric cases are not described, and only raw numbers are reported.

Kianpoor et al. (Reference Kianpoor, Bakhshani and Daemi2006) is also a lower-quality cross-sectional study. It bears well on the study design that the participants were screened twice and according to validated DSM-IV standards of panic disorder. However, the moderate sample size (N = 66), panic disorder qualification criteria and convenience recruitment of the sample are significant limitations to its accuracy and generalizability. Furthermore, the singular reporting of percentages does not reflect well on the rigor of the measurement tools or statistical analyses (31 (47.0%) cases were polygamous and 26 (39.0%) were monogamous).

Ozkan et al. (Reference Ozkan, Altindag, Oto and Sentunali2006) provide another example of a strong cross-sectional, prevalence study. The sample is large and appears representative including all polygamous women within the municipality with monogamous women matched for age and selected randomly (N = 138). The employed measurement tools were again validated and reliable. Finally, the data were assessed through rigorous statistical analyses including chi-square, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and a post hoc Bonferroni test (Somatoform Dissociation Questionnaire (SDQ): F(3, 135) = 20.10, p < 0.001). The only limitations to this study include its generalizability to two-wife families and women over 18 years old and its lack of statistical control for other potentially contributing variables to one's mental health.

Finally, Patil & Hadley (2008) is a mediocre quality cross-sectional, prevalence study. The large sample and the sample type (randomly sampling from one village and conducting a census in another) indicate strong representation (N = 408). The inclusion of some third and fourth wives also opens up the generalizability of the findings. The weaknesses of the study, however, are of concern. The study was conducted during the post-harvest, dry season or the period of increased food and decreased labour, possibly biasing the study findings (symptoms of anxiety (HSCL-25): χ2(2) = 0.7, p = ns; symptoms of depression (HSCL-25): χ2(2) = 0.76, p = ns; emotional distress (HSCL-25): χ2(2) = 0.52, p = ns). The employment of only one assessment tool, though a validated measure, may limit the reliability of the findings further. Finally, the statistical analyses and controls are inconsistently reported.

Themes and findings

The selected literature uses many different measures of marital status and mental health, inhibiting the conduct of a meta-analysis; a summary of included study findings, however, is presented in Table 5 and a brief narrative summary of common outcomes is provided here. As aforementioned, three included studies indicated mixed findings and 15 reported significant outcomes. Thus, 18 of the 22 included articles, or 11 of the 12 studies to directly examine prevalence, evidence a significant difference in mental health according to marital status, with the soundest and most rigorous methods espousing. These significant differences are reported to exist in the higher prevalence of somatization, depression, anxiety, hostility, paranoid ideation, psychoticism, general symptom severity (GSI), positive symptoms total (PST) and psychiatric disorder as well as in the lower ratings of life and marital satisfaction, family functioning and SE in polygamous wives.

Of the four studies utilizing the SRQ-20 measurement of psychological distress or neurotic disorder, only two studies clearly report an analysis of marriage type and SRQ-20 score (Abou-Saleh et al. Reference Abou-Saleh, Ghubash and Daradkeh2001; Maziak et al. Reference Maziak, Taghrid, Fawaz, Fouad and Nael2002; Daradkeh et al. Reference Daradkeh, Alawan, Al Ma'aitah and Otoom2006; Abbo et al. Reference Abbo, Ekblad, Waako, Muhwezi, Musisi and Okello2008). Both of these studies found a significant difference in scores between monogamous women and polygamous women (Maziak et al. Reference Maziak, Taghrid, Fawaz, Fouad and Nael2002; Abbo et al. Reference Abbo, Ekblad, Waako, Muhwezi, Musisi and Okello2008). Abbo et al. (Reference Abbo, Ekblad, Waako, Muhwezi, Musisi and Okello2008) employed a score cut-off point of 6 (i.e., respondents answered positively to at least six of the questions) and found that polygamous women were over three times as likely to report psychological distress than monogamous women (OR (95% CI 1.38–10.98) = 3.62, p = 0.012). Maziak et al. (Reference Maziak, Taghrid, Fawaz, Fouad and Nael2002) used a score cut-off point of 8 and also found that polygamous women were more likely to report symptoms of neurotic disorder (OR (95% CI 1.5–13.4) = 4.5, p = 0.003). Furthermore, Maziak et al. (Reference Maziak, Taghrid, Fawaz, Fouad and Nael2002) conducted logistic regression models for cut-off scores of 8 and 12 and found that polygamy was a significant predictor of psychiatric distress in both models, (OR (95% CI 1.1–12.0) = 3.3, p = 0.03) and (OR (95% CI 2.5–33.2) = 9.1, p < 0.001), respectively. Other significant predictors of psychiatric distress in the sample included place of residence, respondent's education, physical abuse, age and age at marriage.

Al-Krenawi (Reference Al-Krenawi2004), Al-Krenawi (Reference Al-Krenawi2010), Al-Krenawi & Graham (Reference Al-Krenawi and Graham2006b), Al-Krenawi et al. (Reference Al-Krenawi, Graham and Gharaibeh2011) and Al-Krenawi & Slonim-Nevo (Reference Al-Krenawi and Slonim-Nevo2008) used a combination of the following measurement tools: the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (H-SCL-90), the McMaster FAD, the ENRICH questionnaire, the Life Satisfaction scale (SWLS), and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem scale. As shown in Table 5, somatization, depression, anxiety, hostility, paranoid ideation, general symptom severity (GSI), decreased marital satisfaction and problematic family functioning appear more prevalent among polygamous respondents in all five studies. Psychoticism, PST, low SE and decreased life satisfaction are also reported across multiple studies (Al-Krenawi, Reference Al-Krenawi2004, Reference Al-Krenawi2010; Al-Krenawi & Graham, Reference Al-Krenawi and Graham2006Reference Al-Krenawi and Grahamb; Al-Krenawi & Slonim-Nevo, Reference Al-Krenawi and Slonim-Nevo2008; Al-Krenawi et al. Reference Al-Krenawi, Graham and Gharaibeh2011). In a regression analysis, however, Al-Krenawi & Slonim-Nevo (Reference Al-Krenawi and Slonim-Nevo2008) found that marital status (i.e., polygamy v. monogamy) combined with economic status only accounts for 5.4% of the variance in SE and 21.1% of the variance in family functioning and that, indeed, polygamy does not account for any of the variance in the previously listed categories of the BSI. Alternatively and more promisingly, a regression analysis revealed family functioning as the best predictor of all noted symptoms, explaining anywhere from 15.1% to 26% of the variance.

Discussion

Strengths and limitations

As previously addressed, the included studies sustain a number of strengths and limitations. First of all, for an often neglected topic and potentially difficult to access population, the multiplicity of identified studies is quite remarkable. Additional strengths of the selected studies include some replication, frequent utilization of validated measures, decent sample sizes, efforts toward representative samples and initial attempts at regression analyses. Unfortunately, however, due to scope of this review and wide variation across countries, cultures, beliefs, study populations and research tools, a meta-analysis was not conducted. Furthermore, the included studies merely relay comparative statistics of significance between monogamous and polygamous women, rather than actual prevalence rates, and may be flawed by publication bias.

As for strengths and limitations of this review, it is again noteworthy that this systematic review fills a gap in the literature. As this review aims to provide a transparent, replicable synthesis and quality assessment of all available quantitative and qualitative research of the impact of polygamy on women's mental health, it would seem valuable for the provision of relevant and timely information for direct practice, program development and research. Unfortunately, a few limitations to this review of note include the exclusion of studies not published in English, the inability to access five potentially relevant papers, and the employment of only two research databases. Furthermore, despite best efforts to search the gray literature, some relevant studies may have been missed.

Implications for practice

Although limited by the mixed methodological quality and considerable diversity across populations, cultures, countries, study designs, measurement tools and outcomes, a few overarching implications for practice can be garnered from the selected studies. First, it can be assumed that polygamous women are at-risk of experiencing psychological and emotional distress. Second, primary healthcare centres may be the most viable access point of treatment for polygamous women. And lastly, the best predictors of mental-health outcomes may not be marital status itself, but other moderating and mediating variables.

Based on the presented evidence, there appears to be a significant relationship between marital status and mental health. Consequently, it is important that practitioners, community leaders and policy-makers working with polygamous populations be aware of their substantive risk for a number of psychological and emotional disturbances. Appropriate care and treatment should accordingly be made available and accessible. Furthermore, special attention may need to be paid to senior wives as some studies distinguish them as particularly vulnerable to psychological distress (Al-Krenawi, Reference Al-Krenawi2001, Reference Al-Krenawi2010; Al-Sherbiny, Reference Al-Sherbiny2005; Ozkan et al. Reference Ozkan, Altindag, Oto and Sentunali2006; Al-Krenawi & Slonim-Nevo, Reference Al-Krenawi and Slonim-Nevo2008; Al-Krenawi et al. Reference Al-Krenawi, Graham and Gharaibeh2011).

In terms of accessibility, primary healthcare services may, for the present, be the best platform for identifying and treating psychological disorders and symptoms in polygamous women. Al-Krenawi & Graham (Reference Al-Krenawi and Graham2006b) found that while only 4% of sampled women were referred to mental-health services, some 84% used their community's primary healthcare centre. In other words, the participants, all of whom sustained mental-health complaints, more readily sought help from their community health clinic than from their local mental-health services. Furthermore, as traditional healing practices have also been found among participants and shown to lessen psychological distress (Al-Krenawi & Graham, Reference Al-Krenawi and Graham1999a; Abbo et al. Reference Abbo, Ekblad, Waako, Muhwezi, Musisi and Okello2008), traditional healers may present another viable conduit through which to offer future interventions.

Finally, some of the included studies point to specific moderating and mediating variables besides marital status itself which may prove helpful in the design and implementation of interventions for polygamous women with psychological distress. Maziak et al. (Reference Maziak, Taghrid, Fawaz, Fouad and Nael2002) point to education as a potential protective factor. Furthermore, and possibly more substantively, the findings of the Al-Krenawi & Slonim-Nevo (Reference Al-Krenawi and Slonim-Nevo2008) study point to family functioning as a potential mediating variable. Assuming this relationship is valid, the address and improvement of family functioning by an intervention could have a substantive impact on a polygamous woman's mental health and symptomatology. However, according to the same regression analysis, economic status may be another mediating variable by which to address psychological distress in polygamous women (Al-Krenawi & Slonim-Nevo, Reference Al-Krenawi and Slonim-Nevo2008).

Directions for future research

Future studies should look to promote larger, more representative and random sampling in various different cultures and societies; a standardization of measuring tools; more rigorous and congruent statistical analyses; and better transparency in reporting. Furthermore, all studies should anticipate and facilitate the conduct of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Finally, in these strides, it is suggested that the Al-Krenawi (Reference Al-Krenawi2004), Al-Krenawi & Graham (Reference Al-Krenawi and Graham2006b), Al-Krenawi et al. (Reference Al-Krenawi, Graham and Gharaibeh2011), Al-Krenawi & Slonim-Nevo (Reference Al-Krenawi and Slonim-Nevo2008) and Ozkan et al. (Reference Ozkan, Altindag, Oto and Sentunali2006) studies are particularly strong models for replication and exploration.

On a more conceptual level, however, future studies also need to move away from a singular focus on the structure of the family and review the intricacies and mediating effects of family dynamics (Elbedour et al. Reference Elbedour, Onwuegbuzie, Caridine and Abu-Saad2002; Al-Krenawi & Slonim-Nevo, Reference Al-Krenawi, Slonim-Nevo and Ungar2005b). The findings of the Al-Krenawi & Slonim-Nevo (Reference Al-Krenawi and Slonim-Nevo2008) study would also seemingly support this objective as family functioning was revealed by regression analysis to be the best predictor of all inventoried symptoms. The value of qualitative work is further suggested to this same end of better understanding the dynamics and intricacies of polygamy from within its own framework.

Finally, continued research of the psychological impact of polygamy on women needs to be directed with the specific intention of informing or designing preventative or intervening approaches. Indeed, according to Slonim-Nevo & Al-Krenawi (Reference Slonim-Nevo and Al-Krenawi2006), future research needs to focus on ‘developing, implementing and evaluating family intervention programs for polygamous families among different communities in the world’.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current state of research reveals with moderate confidence a more significant prevalence of mental-health issues in polygamous women as compared to monogamous women. Of mention are the principally significant levels of somatization, depression, anxiety, hostility, paranoid ideation, psychoticism, psychiatric disorder, general symptom severity (GSI), decreased life and marital satisfaction, problematic family functioning and low SE across the included research study results. Thus, it is important that practitioners, community leaders and policy-makers working with polygamous populations be aware of their substantive risk and make appropriate care and treatment available and accessible.

Declaration of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.