Introduction

A disproportionately large number of seabirds are threatened due to the diverse range of threats that affect them both at sea and on their breeding sites (Croxall et al. Reference Croxall, Butchart, Lascelles, Stattersfield, Sullivan, Symes and Taylor2012). The spectacled petrel Procellaria conspicillata Gould only breeds at Inaccessible Island (37°18′S, 12°41′W) in the Tristan da Cunha group, central South Atlantic Ocean, although historically a population may have bred on Amsterdam Island and/or St Paul Island in the southern Indian Ocean (Ryan Reference Ryan1998). Substantial numbers were killed by longline fishing gear mainly off the east coast of South America during the 1990s, resulting in the species being listed as Critically Endangered (Ryan Reference Ryan1998, BirdLife International 2004). However, subsequent surveys indicate that the breeding population has increased over the last decade (Ryan & Moloney Reference Ryan and Moloney2000, Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Dorse and Hilton2006, Ryan & Ronconi Reference Ryan and Ronconi2011), resulting in their conservation status being changed to Vulnerable (BirdLife International 2010). The population growth of spectacled petrels is thought to be due to their ongoing recovery following the disappearance of feral pigs Sus scrofa L., an introduced predator of seabirds, from Inaccessible Island sometime around the turn of the 20th century (Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Dorse and Hilton2006). Despite this positive trend, modelling of spectacled petrel demographics shows that they are susceptible to even small changes in their mortality rate (Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Dorse and Hilton2006), and they continue to be killed in a range of fisheries off eastern South America (Bugoni et al. Reference Bugoni, Mancini, Monteiro, Nascimento and Neves2008a, Reference Bugoni, Neves, Leite, Carvalho, Sales, Furness, Stein, Peppes, Giffoni and Monteiro2008b, Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Abreu, Pons, Ortiz and Domingo2010). It is thus important to understand the species’ foraging range, and especially their overlap with fisheries that impact seabirds. Changing of target species and fishing areas can affect the mortality of seabird species (Reid et al. Reference Reid, Hindell and Wilcox2012).

There is limited information about the at-sea distribution of spectacled petrels. Enticott & O'Connell (Reference Enticott and O'Connell1985) compiled sightings data for South Atlantic waters between 30 and 55°S. During the summer breeding season, most sightings were in the central South Atlantic Ocean, close to Inaccessible Island, with others observed from the South American to the South African coasts (Enticott & O'Connell Reference Enticott and O'Connell1985). Winter records were mainly to the west of Inaccessible Island as far as the coast of South America (Enticott & O'Connell Reference Enticott and O'Connell1985). Thirty were observed over the Walvis Ridge during February 2000, but none was observed along the southern African shelf edge (Camphuysen & Van der Meer Reference Camphuysen and van der Meer2000), where they are a regular but scarce visitor, mainly in summer (Hockey et al. Reference Hockey, Dean and Ryan2005). In the western South Atlantic, flocks of up to 200 have been recorded attending longline fishing vessels (Bugoni et al. Reference Bugoni, Mancini, Monteiro, Nascimento and Neves2008a; Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Domingo, Abreu and Braziero2011). Breeding birds return to Inaccessible Island in September, lay in late October, and the chicks fledge in March (Ryan Reference Ryan2007). However, unlike the closely-related white-chinned petrel Procellaria aequinoctialis L., at least some adults return to the island after moulting to clean out their burrows in May–June (Rowan et al. Reference Rowan, Elliott and Rowan1951).

Prior to our study, the only tracking data for spectacled petrels were of five individuals of unknown age captured during fishing operations off Brazil in winter (Bugoni et al. Reference Bugoni, D'Alba and Furness2009). Four birds tracked for 17–20 days during August 2007 remained within the Brazilian exclusive economic zone (EEZ), while one bird caught on 17 August 2006 moved to waters near Inaccessible Island in late September before returning almost to Brazil when its transmitter failed on 4 October (Bugoni et al. Reference Bugoni, D'Alba and Furness2009). In this paper we report the foraging ranges of eight adult spectacled petrels caught at Inaccessible Island in early summer during their incubation period, with some individuals tracked throughout the breeding period. We also assess their exposure to longline fishing effort in the region.

Methods

Spectacled petrels were caught in the afternoon as they returned to a breeding colony in lower Ringeye valley (unofficial name) (37°17.5′S, 12°40.8′W) on the summit of Inaccessible Island. Four were caught on 29 October 2009 at the peak of egg laying (Ryan Reference Ryan1998) and a further four on 22 November 2009, roughly midway through the incubation period (Table S1, which will be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954102013000266). The breeding status of the birds was not confirmed, and they probably included a mix of breeding and non-breeding adults. All birds were tracked using Argos satellite transmitters (PTTs, 32 g, Sirtrack, Havelock North, New Zealand) which were attached to the centre of the bird's back using Tesa tape and superglue to secure them to a group of back feathers as well as four sub-dermal sutures (MacLeod et al. Reference MacLeod, Adams and Lyver2008).

After leaving Inaccessible Island, a bird was inferred to return to the island if a fix was obtained within 0.2° of the island's position, or within 2° of the island's position followed by no positional record for over 24 hours. Birds returning to the island were assumed to be still breeding (or loafing), and their foraging trips ascribed to different stages of the breeding season (Table S2, which will be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954102013000266). Given limited data on spectacled petrel breeding phenology (Rowan et al. Reference Rowan, Elliott and Rowan1951, Ryan Reference Ryan2007), we based these periods on the approximate time of laying (late October, Ryan Reference Ryan1998) and assumed similar incubation and chick-rearing periods as the closely-related white-chinned petrel (from Marchant & Higgins Reference Marchant and Higgins1990). Trips during November–December were classified as incubation trips, January to their final visit to the island as chick provisioning, and from then onwards as post-breeding. When a trip began during incubation and returned during the chick-rearing period it was classified based on whichever period was longer (mainly December = incubation, mainly January = chick-rearing). Birds were classified as non-breeders if they made a few short trips early in the breeding season before permanently leaving when they were defined as post-breeders.

Data collected by biotagging have inherent difficulties due either to the unevenness of data collection, or the inaccuracy of some data (Jonsen et al. Reference Jonsen, Mills, Flemming and Myers2005, Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Thomas, Wilcox, Ovaskainen and Mathiopoulos2008). This can cause complications for analysing the data. For example, having positions equally spaced in time makes it easier to determine how animals structure foraging trips. Therefore, each trip was analysed with a state-space model (SSM) using the bsam package (version 0.21; Jonsen et al. Reference Jonsen, Basson, Bestley, Bravington, Patterson, Pedersen, Thomson, Thygeson and Wotherspoon2012) in R (version 2.15.0, http://cran.r-project.org). This assumes that animals engage in a random walk, frequently changing behaviour. State-space models are time-series models that allow future states of a system to be predicted from previous positions using a process model (Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Thomas, Wilcox, Ovaskainen and Mathiopoulos2008). State-space models such as bsam combine a hypothetical mechanistic model of animal movements (called a process model) with an observation model, which give a probability of obtaining a particular observation, conditional on the animal's true position. This is termed the animal's state (Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Thomas, Wilcox, Ovaskainen and Mathiopoulos2008), and can include its mode of movement (foraging or migrating) as well as its position (Patterson et al. Reference Patterson, Thomas, Wilcox, Ovaskainen and Mathiopoulos2008). By formulating a non-linear SSM it is possible to infer animal positions for times when there are no observations (Jonsen et al. Reference Jonsen, Mills, Flemming and Myers2005), which is important for allowing an even spread of position estimates. Bsam uses a Bayesian approach with a Markov chain Monte Carlo method (MCMC) to identify foraging areas. The model estimates the probability that any position is in one of two states: transiting (1) or foraging (2) (Jonsen et al. Reference Jonsen, Myers and James2007). Each iteration of the model identifies a position as one of these states. The probability of which state each position is in is determined by the mean of all iterations. We defined positions with state greater than 1.7 as foraging. The MCMC used 20 000 iterations after a burn-in of 10 000 iterations to eliminate the effects of initial values. The chain was thinned by keeping every tenth record, to eliminate any auto-correlation, and to deal with memory issues.

Trips needed to have at least 20 PTT positions to identify foraging areas in the SSM, because the model relies on a time series of data and requires sufficient data to converge on a reliable result (I. Jonsen, personal communication 2012). Trips with fewer than 20 positions were short (1–10 days). Ignoring foraging areas during these trips biased against the Mid-Atlantic Ridge area, as most short trips were made to this area. Although no foraging areas were inferred for these trips, they were used to calculate trip length and distance from Inaccessible Island. Total trip length and distance from Inaccessible Island were calculated using great circle routes. Differences in trip speed and length between breeding seasons, and between night and day were tested using the glm function in R (version 2.15.0, http://cran.r-project.org). Kernel smoothing was used on the positions using the kde function from the package ks (version 1.8.11) in R using a multivariate normal density. Bins were set at their ideal dimensions using the Hpi function in the ks package. Kernel contours were set at 50, 75 and 90%.

Modelling the effect of environmental conditions

Ocean depth data (two minute gridded global relief data) were downloaded from the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration's National Geophysical Data Center (http://www.ngdc.noaa.gov/mgg/fliers/01mgg04.html, accessed February 2007). Sea surface temperature (SST) and Aqua Modis chlorophyll a were downloaded from SeaWifs (http://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/, accessed June 2012) using monthly data per 4 x 4 km grid cell. Mean sea level anomaly (MSLA) data were obtained from Aviso at http://www.aviso.oceanobs.com (accessed June 2012). Environmental variables chosen were readily available and frequently used as descriptors of oceanic conditions in studies of this type (e.g. Wakefield et al. Reference Wakefield, Phillips, Trathan, Arata, Gales, Huin, Robertson, Waugh, Weimerskirch and Mathiopoulus2011).

The distribution of foraging spectacled petrels in relation to environmental conditions was modelled following the approach of Aarts et al. (Reference Aarts, MacKenzie, McConnell, Fedak and Mathiopoulus2008) and Wakefield et al. (Reference Wakefield, Phillips, Trathan, Arata, Gales, Huin, Robertson, Waugh, Weimerskirch and Mathiopoulus2011). This creates pseudo-absence data to control for areas where the tracked animal could have gone, but did not (Aarts et al. Reference Aarts, MacKenzie, McConnell, Fedak and Mathiopoulus2008, Wisz & Guisan Reference Wisz and Guisan2009, Wakefield et al. Reference Wakefield, Phillips, Trathan, Arata, Gales, Huin, Robertson, Waugh, Weimerskirch and Mathiopoulus2011). Pseudo-absences allow tracks to be analysed using logistic regression methods, scoring data from tracked birds as 1 and pseudo-absences as 0. Choice of area for pseudo-absences is important, as they need to be realistic. Spectacled petrels have different restrictions depending on their breeding activities. Breeding birds are restricted by having to return to their breeding colony, and hence are central place foragers. For breeding birds, habitat availability decreases with distance from the colony. Tracking location distances from the colony by breeding spectacled petrels approximated a log-normal distribution. We chose pseudo-absences by generating three random positions using a normal distribution for latitude and longitude with Inaccessible Island as the mean, and standard deviations based on the observed movements of tracked birds (12° of longitude throughout the breeding period, and 4° latitude during incubation and 3° during chick-rearing). Loafers/pre-breeders making short trips and returning to the colony during November were treated in the same model with incubating birds. Non-breeding spectacled petrels, while not restricted to their colonies, were not observed to leave the Atlantic Ocean. Therefore, pseudo-absences were randomly chosen from within the South Atlantic Ocean between 20 and 45°S. For each observed position, three pseudo-absences were chosen using a distribution dependent on the bird's activity at the time of that observation (Wakefield et al. Reference Wakefield, Phillips, Trathan, Arata, Gales, Huin, Robertson, Waugh, Weimerskirch and Mathiopoulus2011).

We modelled the tracking data using a Generalized Additive Mixed Model (GAMM) using the mgcv (version 1.7-13) package in R. Individual birds were treated as random effects. Fixed effects used in the model were latitude and longitude as interacting terms, SST, chlorophyll a, water depth and MSLA. Distance from the breeding island was tested for breeding birds. This could not be combined with latitude and longitude as they were correlated. We took a Bayesian view that all variables chosen for fixed effects were components of the world, and therefore should be presented, rather than using any form of model selection to narrow down variables (Bolker Reference Bolker2008). This is appropriate as the model is descriptive rather than predictive.

Overlap with fisheries

Longline fishing effort data are presented at the finest spatial resolution possible. Data for the Atlantic Ocean were obtained from the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT; http://www.iccat.es/en/accesingdb.htm, June 2012), with effort averaged annually over five years (2006–10) at a 5 x 5° resolution.

Results

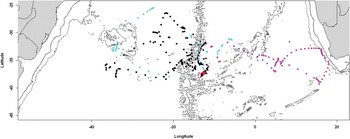

Transmission data were received up to 1 May 2010, more than six months after deployment (average duration 130 ± 53 days). The number of positions recorded averaged 523 ± 332 per bird (range 118–991, Table S1, which will be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954102013000266). One bird tagged on 29 October either was a non-breeder or it deserted after handling, because it departed the island and did not return, despite being tracked until May 2010 (Table S2, which will be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954102013000266). It spent the summer and autumn in oceanic waters almost exclusively east of Inaccessible Island, foraging mainly over the Walvis Ridge but also visiting the shelf break off South Africa and down to 41°S south-west of the Agulhas Bank (red symbols in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Positions of seven post-breeding spectacled petrels (four positions per day derived from a state-space model). Different colours denote different birds. Inaccessible Island is the red diamond at 37°S, east of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Depth contours: 1000 m continuous line, 3000 m dotted line.

All other birds returned to the island at least once. Four of these birds departed the island 9–20 days after deployment, making only 2–4 (mean 3.0 ± 0.8 SD) short foraging trips away from the island in this time (Table I, Fig. 2). They may have been breeders that failed during incubation, but it is more likely that they were non-breeding or pre-breeding adults, given their short foraging trips compared to the three other presumed breeding birds that continued to visit the island throughout the incubation period (Fig. 3, Table I). While based at Inaccessible Island, the presumed non-breeders concentrated their foraging activity along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, with 50% of locations within 500 km of the island (Fig. 2). After leaving Inaccessible Island during November–December, all four travelled west towards the east coast of South America, where they remained for the rest of the time they were tracked. They spent most time on the shelf and along the shelf break (mean 45%, range 28–50% of time over water < 1000 m deep and mean 20% (range 16–25%) over water 1000–3000 m deep), but two birds also spent 13% of their time over the Rio Grande Rise and adjacent oceanic waters (dark blue and tan symbols in Fig. 1). Along the shelf break, each favoured slightly different areas, with one centred at 36–47°S off Argentina (yellow symbols), one at 32–38°S off Uruguay and Argentina (green symbols), one at 29–35°S off Brazil and Uruguay (dark blue symbols) and one at 24–31°S off Brazil (tan symbols).

Table I Parameters of spectacled petrel foraging trips (mean and range) during each stage of the breeding season, reporting trip duration, minimum path length and maximum distance from the colony.

Fig. 2 Positions of spectacled petrels inferred to be non-breeding during the incubation period (conventions as Fig. 1). One bird (tan track) travelled almost 1000 km north-west of Inaccessible Island, then failed to transmit for four days, whereupon it was back at the island.

Fig. 3 Positions of spectacled petrels inferred to be breeding during the incubation period (November–December; conventions as Fig. 1).

The remaining three adults returned to the island multiple times throughout the breeding season and were assumed to be breeding. The transmitter of one of these failed in early January, and thus only provided data during the incubation period, whereas the other two continued transmitting until the second half of April 2010 (Table S1, which will be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954102013000266). However, one failed to return to the island after late February, presumably because its breeding attempt failed. The three breeding birds made longer trips during incubation than the four non-breeders/pre-breeders (Table I), but their trips became shorter towards the end of December when the eggs hatch. Two foraged predominantly west of Inaccessible Island (black and light blue symbols) whereas one travelled east to South Africa (pink symbols, Fig. 3). They exploited quite a wide latitudinal range, executing long, looping tracks. After the chicks hatched, the two remaining tagged breeding birds foraged almost exclusively in oceanic waters, although one bird reached coastal waters off southern Brazil. Most time was spent in the central South Atlantic, concentrated over the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, with fairly well-marked latitudinal segregation between the two birds (Fig. 4). After breeding, one of them (black symbols) went to the Rio Grande Rise before its battery failed. The other bird (light blue symbols) also initially went to the Rio Grande Rise, but then moved east as far as the Walvis Ridge (Fig. 1). During both incubation and chick-rearing, 40% of locations were recorded between 10–20°W, and a further 23% were recorded between 20–30°W.

Fig. 4 Positions of breeding spectacled petrels during the chick-rearing period (conventions as Fig. 1).

There was no evidence that spectacled petrels were less active at night than during the day (Table II and Table S3, which will be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954102013000266). However, birds travelled further and faster during chick-rearing than during other breeding stages (Table II and Table S3, which will be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954102013000266).

Table II Mean (± SD) distance travelled by spectacled petrels and their speed during day and night at each stage of the annual cycle.

Characterizing foraging areas

During the breeding season (both incubation and chick provisioning) spectacled petrels were more likely to be north and north-west of Inaccessible Island than south or east of the island (comparisons with available habitat based on a normal distribution; incubation: effective degrees of freedom (edf) = 18.7, χ2 = 50.2, P < 0.01; chick provisioning: edf = 8.3, χ2 = 22.6, P < 0.01). When compared to a model of distance from the island, they showed flat partial residuals, indicating that the assumptions of the model were reasonable. During incubation, spectacled petrels were distributed in water with oceanographic and bathymetric features that were similar to what would be expected if they were using the area randomly (SST: edf = 1.0, χ2 = 0.9, P = 0.34; chlorophyll: edf = 1.0, χ2 = 2.5, P = 0.11; water depth: edf = 1.0, χ2 = 1.0, P = 0.31; mean sea level anomaly: edf = 4.0, χ2 = 6.7, P = 0.15; adjusted r 2 = 0.37). During the chick-rearing period they used habitats that were no different from random locations (SST: edf = 3.2, χ2 = 2.6, P = 0.51; chlorophyll: edf = 1.0, χ2 = 0.7, P = 0.40; water depth: edf = 1.0, χ2 = 0.7, P = 0.39; mean sea level anomaly: edf = 1.0, χ2 = 0.9, P = 0.35; adjusted r 2 = 0.53).

Non-breeding birds were modelled as having water in the South Atlantic being equally available (Fig. 5; adjusted r 2 = 0.55). Spectacled petrels were most likely to occur off the coast of South America, with other peaks over the Walvis Ridge and east of the Rio Grande Rise near 30°S (edf = 27.4, F = 20.4, P < 0.01). They also preferred waters >12°C (edf = 6.3, F = 6.8, P < 0.01; Fig. 5a) with low chlorophyll concentrations (edf = 1.0, F = 10.6, P < 0.01; Fig. 5b), concentrating over shelf/slope waters c. 1000 m deep (edf = 8.4, F = 19.0, P < 0.01; Fig. 5c) in areas with no sea level anomaly (edf = 3.1, F = 3.4, P = 0.02; Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5 Plots of selected fixed effects models of non-breeding spectacled petrels. Y-axes show the partial residuals once the effects of other variables have been removed. a. Sea surface temperature (°C), b. chlorophyll a (mg m-3), c. water depth (m), and d. mean sea level anomaly (cm).

Overlap with fisheries

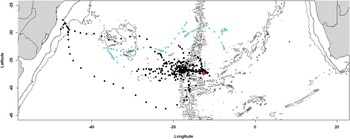

South of 10°S, most pelagic longline fishing effort occurred near the coasts of either South America, or South Africa, or north of 15°S (Fig. 6). Out of 112 5 x 5° blocks, 25 (22%) had an average of over one million hooks set in them each year. All tracked birds visited at least one of these blocks with large fishing effort. Out of 3906 positions for tracked birds, 643 were within blocks with high fishing effort, indicating that tracked birds spent 16% of their time in these areas (range 1–33% per bird). Overlap with high risk blocks was lowest for pre-breeders/loafers (1%), intermediate for breeding adults (6% during incubation and 1% during chick-rearing; 3% overall) and highest for non-breeding adults (22%).

Fig. 6 Mean annual pelagic longline fishing effort in South Atlantic Ocean taken from International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT) data for the period 2006–10. Kernel densities of spectacled petrels overlayed (yellow = 90%, orange = 75%, red = 50%).

Discussion

All eight spectacled petrels remained within the South Atlantic Ocean, which sightings at sea suggest is the species’ main range (Enticott & O'Connell Reference Enticott and O'Connell1985). Spectacled petrels have not been recorded in the south-east Pacific, and are rare off the east coast of South Africa (Hockey et al. Reference Hockey, Dean and Ryan2005). Small numbers have been seen in recent sight records from the vicinity of Amsterdam and St Paul islands in the south-central Indian Ocean (Shirihai Reference Shirihai2007).

While breeding, spectacled petrels are constrained to return to their breeding colonies regularly, limiting their commuting range. In comparison, the closely-related white-chinned petrels regularly travel > 2000 km from their breeding islands while breeding (Weimerskirch et al. Reference Weimerskirch, Catard, Prince, Cherel and Croxall1999, Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Silk, Croxall and Afanasyev2006), while great shearwaters Puffinus gravis O'Reilly breeding on Inaccessible Island travel up to 4000 km (Ronconi et al. Reference Ronconi, Ryan and Ropert-Coudert2010). However, areas of high productivity linked to strong oceanographic features, such as the Brazil-Malvinas confluence or the South American continental shelf edge are > 3000 km from Inaccessible Island (Stramma & Peterson Reference Stramma and Peterson1990, Stramma & England Reference Stramma and England1999, Wainer et al. Reference Wainer, Gent and Goni2000), and thus may be too far for regular commuting by breeding spectacled petrels. None of the incubating birds (n = 3) and only one of the two birds tracked during the chick-rearing period visited the South American continental shelf (Fig. 4). The African continental shelf edge is closer at around 2500 km, yet only one incubating bird visited these waters (Fig. 3). Spectacled petrels generally dispersed farther from the colony during chick-rearing than incubation. However, sample sizes were small (especially during chick-rearing) and this result might have been influenced by uncertainty when the eggs hatch. Trips were very short in late December and early January, around the inferred time of hatching, as is typical of procellariiforms (Warham Reference Warham1990). The bird tracked during the late chick-rearing stage made a few long trips (11–25 days), which inflated the average trip length during chick-rearing.

Non-breeding spectacled petrels off Brazil exhibited similar movements during the day and night (Bugoni et al. Reference Bugoni, D'Alba and Furness2009). Breeding birds studied here showed similar patterns.

Apart from occasional long-distance trips, breeding spectacled petrels spent most of their time over the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Models of their movements suggest that the strongest determinant of their distribution was to move north-west of the island. Other environmental parameters had relatively little effect on their distribution, with only a weak suggestion that they preferred warmer and shallower waters, which is consistent with their movements north of the island and over the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Although relatively weakly developed in the central South Atlantic, the Subtropical Convergence (c. 35–40°S) passes close to Inaccessible Island (Stramma & Peterson Reference Stramma and Peterson1990). The area where breeding spectacled petrels mainly foraged is in the area where the Subtropical Convergence interacts with the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, possibly enhancing local productivity. However, there was only a weak preference for waters with increased chlorophyll concentrations during one of the two breeding periods (incubation). Thus, either spectacled petrels are not using any increased productivity from the Subtropical Convergence, or not at scales measured in this study. Other frontal systems in the region associated with enhanced productivity, such as the sub-Antarctic and Antarctic Polar Front, are situated farther south (Stramma & Peterson Reference Stramma and Peterson1990) in latitudes seldom, if ever, visited by breeding birds.

Following the completion of breeding or breeding attempts, spectacled petrels moved away from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, primarily to the north-west or north-east (Fig. 1). Non-breeding birds often disperse away from areas exploited by breeding birds either to reduce competition or to allow access to more productive areas unavailable to breeding birds (Alerstam Reference Alerstam1991). Non-breeding spectacled petrels typically foraged along the edges of continental shelves or over mid-ocean ridges, concentrating in waters around 1000 m deep. These were the only areas where they spent much time south of the latitude of Inaccessible Island (although this varied between individuals). Of the seven non-breeding birds tracked, four moved to the shelf break off the coast of South America, one remained in oceanic waters of the central South Atlantic, and one moved east of Inaccessible Island, foraging mainly over the Walvis Ridge but also visiting the southern African shelf edge. The transmitter on the other bird failed over the Rio Grande Rise before it was certain where it was going. Three of the four birds that went to South America also visited this area, which was also visited by birds tracked in winter from southern Brazil (Bugoni et al. Reference Bugoni, D'Alba and Furness2009).

Modelling of non-breeding birds indicated they were more likely to use warm and shelf/slope water with relatively low chlorophyll concentrations than would be expected by chance. The most productive water within the area they could potentially forage was predominantly in the south associated with oceanographic features such as the Brazil-Malvinas Confluence and the Antarctic Polar Front, or along the edges of continental shelves. However, spectacled petrels remained largely in subtropical and tropical water north of 35°S, except where they were observed on the shelf break of South America or south-west of South Africa. Subtropical and tropical waters generally are less productive than sub-Antarctic waters (Tomczak & Godfrey Reference Tomczak and Godfrey2003).

Off the east coast of South America, spectacled petrels predominantly forage in areas to the north of those used by white-chinned petrels (Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Silk, Croxall and Afanasyev2006). Off south-eastern Brazil, where both species occur in large numbers in winter, Bugoni et al. (Reference Bugoni, D'Alba and Furness2009) found that spectacled petrels chiefly occur in subtropical and tropical waters, while white-chinned petrels occur in cooler, shallower waters closer to the coast. They found that the two species were segregated by water depth, with spectacled petrels mainly over the continental slope and offshore water (86% of locations > 1000 m water depth), whereas white-chinned petrels mainly occurred on the continental shelf in water around 500 m deep (Phillips et al. Reference Phillips, Silk, Croxall and Afanasyev2006). Our results confirm this preference for relatively warm, oligotrophic waters by spectacled petrels. However, non-breeding birds tended to occur in shallower waters in summer than winter, with 45% of foraging locations over water less than 1000 m deep. Our results thus suggest that spectacled petrels move to shallower waters in summer when fewer white-chinned petrels are present. Our tracking data thus augment the data collected in winter by Bugoni et al. (Reference Bugoni, D'Alba and Furness2009), and confirm the importance of the shelf edge off the east coast of South America between 20 and 40°S for this species. However, Bugoni & Furness (Reference Bugoni and Furness2009) reported that juvenile birds were largely absent from these waters, and it would be interesting to know whether this age class disperses to other areas.

Substantial numbers of spectacled petrels have been killed on longlines off the coast of South America (Bugoni et al. Reference Bugoni, Mancini, Monteiro, Nascimento and Neves2008a, Reference Bugoni, Neves, Leite, Carvalho, Sales, Furness, Stein, Peppes, Giffoni and Monteiro2008b, Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Abreu, Pons, Ortiz and Domingo2010), while only a few have been reported killed off southern Africa (Ryan & Ronconi Reference Ryan and Ronconi2011). Spectacled petrels were among the more commonly caught species in pelagic longline fisheries off Brazil, with a bycatch rate of 0.008 birds per 1000 hooks (Bugoni et al. Reference Bugoni, Mancini, Monteiro, Nascimento and Neves2008a). Much less is known about bycatch in international waters, but fishing effort is reported to be appreciably lower in these waters (Fig. 6). Fisheries data here is averaged over five years and 5 x 5° blocks, while the petrels were tracked for only a single year. Hence there is substantial spatial and temporal mismatch in the datasets, and so they should be interpreted with caution (Torres et al. Reference Torres, Sagar, Thompson and Phillips2013). By spectacled petrels spending most of their time over the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between c. 25 and 40°S, breeding birds had little exposure to longline fishing effort. Nevertheless, they did make some longer trips, ranging as far as South American and southern African waters, where they were more likely to encounter longliners. Post-breeding adults had a significantly greater risk of exposure to longline fisheries, especially off the coast of South America. All tracked birds visited areas with on average heavy longline fishing effort over the last five years. Bugoni et al. (Reference Bugoni, D'Alba and Furness2009) and Jiménez et al. (Reference Jiménez, Abreu, Pons, Ortiz and Domingo2010) showed that pelagic longline fishing effort by Brazilian and Uruguayan domestic fisheries is concentrated in shelf break waters and near the Rio Grande Rise, areas frequently visited by tracked spectacled petrels. A number of other hook and line fisheries known to catch spectacled petrels operate in this area, including hand lining and slow trolling targeting tuna and other species (Bugoni et al. Reference Bugoni, D'Alba and Furness2009). As a result it is important to continue monitoring the population size of spectacled petrels and their interactions with fisheries as their demographic show that they are susceptible to even small changes in their mortality rate (Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Dorse and Hilton2006).

Acknowledgements

We thank Trevor Glass, Tristan Conservation Department, and the Tristan Administrator and Island Council for permission to work on Inaccessible Island. Funds for the satellite transmitters were provided by the David and Lucille Packard Foundation in collaboration with BirdLife International. TAR was funded in part by a grant from the Plastics Federation of South Africa. Logistical support was supplied by the South African National Antarctic Programme (SANAP) and Tristan's Conservation Department. We especially thank Captain Clarence October and the crew of the Edinburgh and Norman Glass. Ross Wanless helped with longline fishing data. We gratefully acknowledge the constructive comments of the reviewers.

Supplemental material

Three supplemental tables will be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954102013000266.