1. Introduction

The structure of turbulent boundary layers developing over rough surfaces has been the object of numerous studies (e.g. see Jimenez Reference Jimenez2004; Castro Reference Castro2007 for a review). One type of rough-bed boundary layers that are particularly relevant for environmental mechanics applications is when the boundary layer develops over sparse larger-scale roughness elements (e.g. irregular arrays of large boulders in mountain rivers). The focus of the present study is on such a type of boundary layers that develop over a bed containing partially burrowed mussels where the protruding parts of the freshwater mussels correspond to the roughness elements. Such large patches/communities/colonies of partially burrowed mussels are referred to as mussel beds. They play a critical role for ecological processes occurring at the water–sediment interface, and affect river dynamics and habitat (Marion et al. Reference Marion2014). A particular feature of this type of rough-bed boundary layers, which are not limited only to rivers but also encountered in marine environments, is that each mussel exchanges mass with the overflow through their syphons, but the net flow exchange is equal to zero. In particular, the excurrent-syphon jet is a source of momentum for the boundary layer. As mussels align with the mean flow and their shells are close to an ellipsoid, their degree of bluntness is much more reduced compared with the typical shapes of the roughness elements (e.g. rectangular cuboids) considered in previous studies of boundary layers developing over arrays of sparse roughness elements (e.g. Yang et al. Reference Yang, Sadique, Mittal and Meneveau2016). Moreover, this type of boundary layers develops in a depth-limited flow, which means that the flow outside of the boundary layer accelerates in the streamwise direction, which is not the case for most types of rough-bed boundary layers investigated in previous experimental and numerical studies. Though the present research is motivated by the need to understand flow structure in rivers containing mussel beds, the main goal of the study is more general and is related to characterising the spatial development of rough-bed boundary layers in depth-limited environments for cases where sparse roughness elements of streamlined shape are present at the bed. The focus of most of the research reported in the literature was on rough-bed boundary layers containing sparse roughness elements with a high degree of bluntness of the roughness elements and on the case where the boundary layer growth is not limited in the vertical direction.

1.1. Background

Freshwater mussels are invertebrates that live on the riverbed substrate with part of their shell being exposed to the water flow. Each mussel contains an excurrent syphon and an incurrent syphon on their posterior side. The discharges through the two syphons are equal at all times. Mussels can vary the flow through their syphons depending on the surrounding flow conditions (e.g. to reduce drag, Di Maio & Corkum Reference Di Maio and Corkum1997). The relative strength of the active filtering is generally characterised by the value of the syphon momentum ratio or filtration velocity ratio, VR, defined as the ratio between the velocity of the flow in the excurrent syphon, Ue , and the bulk channel velocity, U0 (figure 1 a). Using their muscular foot, they can modify their level of burrowing in the substrate. They are generally oriented parallel to the mean flow to reduce drag forces and the probability to be dislocated from the river bed by the overflow.

Figure 1. Computational domain containing the partially burrowed mussels: (a) protruding part of the shell of one mussel showing main geometrical dimensions and bulk velocities through the incurrent and excurrent syphons; (b) positions of the mussels in the simulations conducted with with

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

55 mussels m−2, h/d

$=$

55 mussels m−2, h/d

![]() $=$

0.5; (c) computational mesh in a vertical plane cutting through some of the mussels. The length of the region containing partially burrowed mussels is Lbd

.

$=$

0.5; (c) computational mesh in a vertical plane cutting through some of the mussels. The length of the region containing partially burrowed mussels is Lbd

.

River regions covered by mussel beds are characterised by increased flow resistance, decreased near-bed velocities and increased turbulence away from the bed compared with regions where mussels are very scarce or absent (Nakato, Christensen & Schonhoff Reference Nakato, Christensen and Schonhoff2007; Allen & Vaughn Reference Allen and Vaughn2009; Sansom et al. Reference Sansom, Bent, Atkinson and Vaughn2020; Lazzarin et al. Reference Lazzarin, Constantinescu, Wu and Viero2024). The population density of mussel beds, or the mussel array density,

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

N/Abed

(N is the total number of mussels forming the mussel bed whose total surface is Abed

) is generally less than 200 mussels per square metre in rivers (Coco et al. Reference Coco, Thrush, Green and Hewitt2006; Sansom et al. Reference Sansom, Bent, Atkinson and Vaughn2020). Habitat suitability is a strong function of hydrodynamic conditions that are controlling the capacity of mussels to resist dislocation from the substrate. Flow structure over the mussel bed also controls turbulent entrainment of nutrients into the benthic boundary layer (Nakato et al. Reference Nakato, Christensen and Schonhoff2007).

$=$

N/Abed

(N is the total number of mussels forming the mussel bed whose total surface is Abed

) is generally less than 200 mussels per square metre in rivers (Coco et al. Reference Coco, Thrush, Green and Hewitt2006; Sansom et al. Reference Sansom, Bent, Atkinson and Vaughn2020). Habitat suitability is a strong function of hydrodynamic conditions that are controlling the capacity of mussels to resist dislocation from the substrate. Flow structure over the mussel bed also controls turbulent entrainment of nutrients into the benthic boundary layer (Nakato et al. Reference Nakato, Christensen and Schonhoff2007).

One of the most important ecological functions of large communities of mussels is to filter water (Polvi & Sarneel Reference Polvi and Sarneel2018). The filtering rate of mussels depends on the species and mussel dimensions (Monismith et al. Reference Monismith, Koseff, Thompson, O’Riordan and Nepf1990; Bunt, Maclsaac & Sprules Reference Bunt, Maclsaac and Sprules1993). Active filtering was shown to influence local mixing patterns around the mussels (Nishizaki & Ackerman Reference Nishizaki and Ackerman2017), as well as turbulent kinetic energy distribution in the wake (Sansom et al. Reference Sansom, Bent, Atkinson and Vaughn2020). By consuming phytoplankton and zooplankton, mussels reduce the concentration of nitrates in many rivers where high nitrogen content is a cause of great concern for water quality. The interest in understanding how the various ecological functions of mussels and their capacity to survive at the river bed are affected by hydrodynamics motivates the present study that tries to characterise the structure and growth of the boundary layer generated over a mussel bed under different conditions (e.g. mussel array density, level of mussel burrowing, filtering rate). For example, mussels have a larger probability to survive high flow events in rivers if the mussel bed is situated in a region of low bed shear stress (Morales et al. Reference Morales, Weber, Mynett and Newton2006; Newton, Woolnough & Strayer Reference Newton, Woolnough and Strayer2008). However, very low bed shear stresses may also be detrimental to mussel habitat due to the deposition of fine particles in large quantities. Entrainment of nutrients inside the benthic boundary layer and the rates of consumption are also strongly dependent on hydrodynamic conditions and the characteristics of the mussel bed. A better understanding of hydrodynamic interactions between mussels and their environment is critical to developing more accurate mussel population dynamics models that can predict the dynamics of mussel beds over long periods of time (Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Kozarek, Hornbach, Hondzo and Hong2019).

1.2. Research on flow and transport over mussels and mussel beds

Boundary layers developing over mussel beds have been investigated in the field and in the laboratory (e.g. Monismith et al. Reference Monismith, Koseff, Thompson, O’Riordan and Nepf1990; O’Riordan et al. Reference O’Riordan, Monismith and Koseff1993; Butman et al. Reference Butman, Frechette, Geyer and Starczak1994; Nikora et al. Reference Nikora, Green, Thrush, Hume and Goring2002; Widdows et al. Reference Widdows, Lucas, Brinsley, Salkeld and Staff2002; Morales et al. Reference Morales, Weber, Mynett and Newton2006; Van Duren et al. Reference Van Duren, Herman, Sandee and Heip2006; Folkard & Gascoigne Reference Folkard and Gascoigne2009). Some flume studies used live mussels collected from natural streams (Butman et al. Reference Butman, Frechette, Geyer and Starczak1994; Widdows et al. Reference Widdows, Lucas, Brinsley, Salkeld and Staff2002; Van Duren et al. Reference Van Duren, Herman, Sandee and Heip2006). Other flume studies used artificial mussel models such that mussel filtration and burrowing were completely controllable. For example, in the experiments of Crimaldi, Koseff & Monismith (Reference Crimaldi, Koseff and Monismith2007), the model mussels consisted only of a syphon pair protruding slightly above the smooth bed of the flume. Other experimental studies used dead mussels, or realistic models of such mussels obtained using a computerised tomography scan of a real mussel, but did not account for the syphonal flow (Crimaldi et al. Reference Crimaldi, Thompson, Rosman, Lowe and Koseff2002; Folkard & Gascoigne Reference Folkard and Gascoigne2009; Sansom et al. Reference Sansom, Bent, Atkinson and Vaughn2020). These flume experiments measured vertical profiles of the velocity and turbulence variables only at a limited number of horizontal locations and/or the two-dimensional flow in the symmetry plane of the flume over a limited area. These studies showed that the vertical velocity, turbulent kinetic energy and Reynolds stress profiles were different from those observed in a classical turbulent boundary layer over a rough surface. The limited data from such flume experiments do not allow characterising the spatial development of the boundary layer originating at the leading edge of the mussel bed.

Quinn & Ackerman (Reference Quinn and Ackerman2014) found that the capability of mussels to affect the near-bed flow pattern increases with

![]() $\rho$

N

. Widdows et al. (Reference Widdows, Lucas, Brinsley, Salkeld and Staff2002) observed that high mussel population densities help mitigate local scour such that mussels are less likely to detach from their anchoring positions with increasing

$\rho$

N

. Widdows et al. (Reference Widdows, Lucas, Brinsley, Salkeld and Staff2002) observed that high mussel population densities help mitigate local scour such that mussels are less likely to detach from their anchoring positions with increasing

![]() $\rho$

N

. Active filtration was found to decrease mussel stability. For isolated mussels, Wu, Constantinescu & Zeng (Reference Wu, Constantinescu and Zeng2020) observed an increase of the streamwise drag force with increasing filtering activity. Several studies found that the filtration velocity ratio, VR, is a primary variable controlling the consumption of nutrients over the mussel bed.

$\rho$

N

. Active filtration was found to decrease mussel stability. For isolated mussels, Wu, Constantinescu & Zeng (Reference Wu, Constantinescu and Zeng2020) observed an increase of the streamwise drag force with increasing filtering activity. Several studies found that the filtration velocity ratio, VR, is a primary variable controlling the consumption of nutrients over the mussel bed.

Only a limited number of experimental studies considered the height of the protruding part of the mussel shell, h, as a key physical parameter. In these experiments, the emerged part of the mussel consisted of only two vertical syphons (Crimaldi et al. Reference Crimaldi, Koseff and Monismith2007; O’Riordan et al. Reference O’Riordan, Monismith and Koseff1993,Reference O’Riordan, Monismith and Koseff1995). A main goal of these studies was to characterise the concentration boundary layer associated with the formation of a phytoplankton-depleted region near the bed due to mussel filtering and consumption (Frechette et al. Reference Fréchette, Butman and Geyer1989). An inverse concentration approach was used to investigate transport and consumption of phytoplankton over mussel-covered beds (Monismith et al. Reference Monismith, Koseff, Thompson, O’Riordan and Nepf1990) in which a neutrally buoyant fluorescent dye of concentration C0 was introduced through the excurrent syphons, while the uniform concentration in the incoming channel flow containing phytoplankton was equal to zero. The coloured dye was assumed to behave as a passive scalar. These studies measured the concentration profiles inside the scalar (phytoplankton depleted) concentration boundary layer and investigated how the phytoplankton distribution is affected by the level of active filtering, mussel burrowing and mussel array density. Characterising the mixing between the filtered water and the incoming flow is important for understanding phytoplankton depletion in natural streams and identifying optimal flow conditions that ensure sufficient food supply to the mussels forming the mussel bed.

Numerical studies using turbulence models that can capture the dynamics of the large-scale coherent structures generated by the protruding part of each mussel were limited to investigating flow past single mussels placed on a smooth bed with and without active filtering (Wu et al. Reference Wu, Constantinescu and Zeng2020; Wu & Constantinescu Reference Wu and Constantinescu2022; Lazzarin et al. Reference Lazzarin, Constantinescu, Di Micco, Wu, Lavignani, Lo Brutto, Termini and Viero2023) and flow past small arrays of semi-burrowed, non-filtering mussels placed on a smooth bed (Constantinescu, Miyawaki & Liao Reference Constantinescu, Miyawaki and Liao2013) in an open channel. Recently, Lazzarin et al. (Reference Lazzarin, Constantinescu, Wu and Viero2024) investigated the simpler case of fully developed flow over arrays of partially burrowed mussels placed on a gravel bed.

1.3. Justification of the approach and research objectives

The main goal of the present study is to characterise the spatial development and structure of the boundary layer forming over a mussel bed consisting of a large array of partially burrowed mussels placed on the smooth bed of a wide open channel (figure 1). The mussels in the array are identical and are oriented with their major axis along the streamwise direction. The freshwater mussels (Lampsilis siliquoidea) in the array are the same as those used by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Constantinescu and Zeng2020). For each test case, h and VR are kept constant for the mussels forming the array. In each simulation, mussels are randomly distributed over the mussel bed, but the mussel array density is fairly constant over subregions that are smaller than the width of the computational domain. Nikora et al. (Reference Nikora, Green, Thrush, Hume and Goring2002) made the important observation that the boundary layer induced by the protruding parts of the mussels develops inside the ‘ambient’ boundary layer present upstream of the mussel bed. The rough-bed boundary layer originating at the leading edge of the mussel bed is an internal boundary layer that is embedded within the ‘ambient’ boundary layer. In the case of rivers and long flumes, the ‘ambient’ boundary layer generally corresponds to fully developed turbulent flow. In the present study, the velocity profile over the smooth channel bed approaching the leading edge of the mussel bed is fully developed. The mussel bed is sufficiently long such that the rough-bed boundary layer reaches the free surface. At this point, the internal boundary layer becomes the new ‘ambient’ boundary layer.

The mean flow and turbulence variables are not two-dimensional (2-D) but rather fairly non-uniform in the spanwise direction up to a certain distance above the top of the mussels. To get an accurate characterisation of the boundary layer and its structure, one needs to be able to estimate width-averaged quantities both above the mussels as well as inside the roughness layer. Trying to characterise the growth of the boundary layer and especially the vertical variation of the mean flow and turbulence variables based only on data collected in a streamwise-vertical plane is not very correct. In the case of flume experiments, estimating width-averaged variables will require performing a series of measurements in many spanwise planes, something that is very time consuming. Moreover, even with particle image velocimetry, it is very difficult to measure the flow field until very close to the deformed surface of the mussel. Given the aforementioned limitations of experimentally based approaches, a numerical approach may be more appropriate. The use of Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) models is not an option given the limited accuracy of such models to predict separated flows and flows with strong adverse pressure gradients. In the case of flow past an isolated mussel, Wu & Constantinescu (Reference Wu and Constantinescu2022) confirmed that RANS predictions of the mean flow, bed shear stresses and drag forces were significantly different compared with those obtained using detached-eddy simulation (DES) even when the RANS and DE simulations were conducted using identical meshes.

The availability of the three-dimensional (3-D), time-averaged (mean) flow fields allows using double-averaging to obtain the equivalent 2-D (width- and time-averaged) boundary layer extending from the channel bed to the free surface. At this point, the mussels are not formally part of the computational domain, but the width-averaged velocity and turbulence variables account for their presence. Though the bottom boundary is flat, the velocity and turbulence profiles are those corresponding to flow over a rough bottom containing sparse toughness elements. The availability of the scalar concentration profiles corresponding to the scalar introduced in the channel through the excurrent syphons allows a full description of the distribution of the phytoplankton concentration inside the boundary layer.

Mussel beds in rivers are generally very long and the flow over the mussel bed eventually becomes fully developed. However, given the large ratio between the average flow depth and the emerged height of the mussels in natural rivers, an understanding of the flow structure in between the leading edge of the mussel bed and the location where the flow becomes fully developed is essential. This is the main goal of the present study that provides, for the first time, a systematic investigation on how the structure of the developing boundary layer is affected by some of the critical flow and geometrical parameters (mussel array density, filtration velocity ratio, height of exposed part of the shell). Some of the main research questions this study tries to answer are as follows.

-

(i) What is the streamwise variation of the boundary layer width and how is the boundary layer growth affected by

$\rho$

N

, VR and h?

$\rho$

N

, VR and h? -

(ii) Are the vertical profiles of the scaled velocity, turbulent kinetic energy and scalar concentration self-similar inside the inertial layer extending in between the top of the mussels and the top of the boundary layer?

-

(iii) Is the mean velocity distribution inside the boundary layer over the mussel bed similar to those observed over other types of boundary layers developing over sparse, large-scale roughness elements? In particular, it will be of interest to check if the model proposed by Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Sadique, Mittal and Meneveau2016) for boundary layers developing over rectangular cuboids also applies for protruding mussels with/without active filtering.

-

(iv) What is the equivalent roughness height inferred from the double-averaged velocity profiles and how is this variable varying with

$\rho$

N

, VR and h? What is the magnitude of the scaling parameter in the law of the wake for boundary layers developing over a mussel bed in an open channel with incoming fully turbulent flow? Is the contribution of the dispersive stresses important to the momentum force balance?

$\rho$

N

, VR and h? What is the magnitude of the scaling parameter in the law of the wake for boundary layers developing over a mussel bed in an open channel with incoming fully turbulent flow? Is the contribution of the dispersive stresses important to the momentum force balance? -

(v) What is the relationship between the mussel bed density and the capacity of the mussels to remove phytoplankton and waste from the water column given the partial re-entrainment of filtered water by the mussels?

The present paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides a brief description of the numerical model and boundary conditions. Also discussed are the series of simulations used to investigate the effects of

![]() $\rho$

N

, VR and h on the development and structure of the 2-D boundary layer. Section 3 discusses the procedure used to calculate the width-averaged variables and then to define the boundary layer thickness. It also discusses how the boundary layer thickness and the maximum values of the width-averaged mean concentration and turbulent kinetic energy vary along the mussel bed. Section 4 proposes a theoretical model based on the model of Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Sadique, Mittal and Meneveau2016) to describe the velocity variation from the bed to the top of the boundary layer and discuss the dispersive and Reynolds shear stresses. The equivalent roughness height is estimated. Sections 5 shows that using proper scaling, the vertical profiles of the streamwise velocity, turbulent kinetic energy and scalar concentration inside the inertial layer become approximately self-similar starting some distance from the origin of the rough-bed boundary layer. Section 6 discusses the effect of the mussel bed density on the average refiltration fraction and the phytoplankton removal efficiency of the mussel bed. The main findings are summarised in § 7 that also provides some conclusions.

$\rho$

N

, VR and h on the development and structure of the 2-D boundary layer. Section 3 discusses the procedure used to calculate the width-averaged variables and then to define the boundary layer thickness. It also discusses how the boundary layer thickness and the maximum values of the width-averaged mean concentration and turbulent kinetic energy vary along the mussel bed. Section 4 proposes a theoretical model based on the model of Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Sadique, Mittal and Meneveau2016) to describe the velocity variation from the bed to the top of the boundary layer and discuss the dispersive and Reynolds shear stresses. The equivalent roughness height is estimated. Sections 5 shows that using proper scaling, the vertical profiles of the streamwise velocity, turbulent kinetic energy and scalar concentration inside the inertial layer become approximately self-similar starting some distance from the origin of the rough-bed boundary layer. Section 6 discusses the effect of the mussel bed density on the average refiltration fraction and the phytoplankton removal efficiency of the mussel bed. The main findings are summarised in § 7 that also provides some conclusions.

2. Numerical model, boundary conditions and matrix of simulations

DES is a hybrid approach that reduces to RANS close to the solid surfaces and to large eddy simulation (LES) over the rest of the computational domain where the eddy viscosity becomes proportional to the square of the local grid spacing. This is done by redefining the turbulence length scale in the production term of the transport equation solved for the modified eddy viscosity. This is the only transport equation solved in the Spalart–Allmaras (S-A) RANS model (Constantinescu et al. Reference Constantinescu, Pasinato, Wang, Forsythe and Squires2002). The viscous sublayer is resolved in the present simulations. No wall functions are used. The IDDES version of the S-A DES is used. The full model equations and coefficients can be found from Spalart (Reference Spalart2000) and Rodi, Constantinescu & Stoesser (Reference Rodi, Constantinescu and Stoesser2013). More details on DES, the basic numerical algorithm and the grid generation methodology are given by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Constantinescu and Zeng2020). Only the main features of the numerical method are reviewed below.

The discretised Navier–Stokes equations are advanced in time using a SIMPLE (Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure Linked Equations) algorithm. The finite-volume solver uses unstructured grids. In addition to the transport equation for the modified eddy viscosity, an advection-diffusion equation is solved for the concentration of the passive scalar, C, introduced through the excurrent syphons (Chang, Constantinescu & Park Reference Chang, Constantinescu and Park2007). The convection terms in the momentum equations are discretised using the third-order MUSCL scheme to keep numerical dissipation low, while those in the transport equations are discretised using the second-order-accurate upwind scheme. The second-order central scheme is used to discretise the diffusive and pressure-gradient terms. The temporal discretisation is implicit and second-order accurate. Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Constantinescu and Zeng2020) discussed validation of the present solver for flow past an isolated semi-buried mussel, same as the mussels used in the present mussel-bed simulations. Their predictions of the mean streamwise velocity and turbulent kinetic energy in the mussel’s wake were close to experimental measurements conducted in a flume at the SUNY University of Buffalo (B. J. Sansom, personal communication 2019). The same study discusses the minimum level of grid refinement needed to achieve grid-independent solutions. The simulations discussed in the present study use the same gridding methodology, mesh quality controls and mesh density around the mussels as the simulations discussed by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Constantinescu and Zeng2020) and Lazzarin et al. (Reference Lazzarin, Constantinescu, Wu and Viero2024).

The mussel geometry (figure 1) in the numerical model was obtained by converting a stereo lithography (STL) file containing the two valves of a dead mussel using AUTOCAD. A short, straight, vertical pipe connecting into the excurrent syphon was then added (figure 1

a). This allows the jet originating in the excurrent syphon to develop without unphysical constraints as it enters the channel. When the active filtering is active, the discharges through the incurrent and excurrent syphons of each mussel are equal. The length and height of the computational domain are L

![]() $=$

6.8 m and D

$=$

6.8 m and D

![]() $=$

0.15 m, respectively. The width of the domain, B, is between 0.25 m and 0.5 m. A smaller value of B is used in the simulations with a high mussel array density. The length of the mussel bed is Lbd

$=$

0.15 m, respectively. The width of the domain, B, is between 0.25 m and 0.5 m. A smaller value of B is used in the simulations with a high mussel array density. The length of the mussel bed is Lbd

![]() $=$

6 m. Up to 150 mussels are placed inside the mussel bed depending on the value of

$=$

6 m. Up to 150 mussels are placed inside the mussel bed depending on the value of

![]() $\rho$

N

. The domain also contains two regions without mussels (figure 1

b).

$\rho$

N

. The domain also contains two regions without mussels (figure 1

b).

Unstructured, Cartesian-like grids containing mostly hexahedral elements are used to mesh the computational domain. Automatic grid refinement is applied in regions containing surfaces of complex shape to provide a conformal mapping of the deformed surface. Trimmed cells are used near the mussels’ surfaces. For the simulations conducted with the largest values of

![]() $\rho_{N}$

, the total number of grid cells approaches 108. Approximately 35 cells are present in between the bed and the free surface. Figure 1(c) shows the mesh near the channel bed in a vertical plane cutting through three mussels. The average cell size increases at larger distances from the emerged part of the shell. Based on the channel Reynolds number and the non-dimensional bed friction velocity over a smooth surface, the average cell size in the directions parallel to the surface of the mussel’s shell is approximately 30 wall units close to the mussel. At most locations, the first grid point in the wall normal direction is situated at less than two wall units from the bed and the mussel’s shell.

$\rho_{N}$

, the total number of grid cells approaches 108. Approximately 35 cells are present in between the bed and the free surface. Figure 1(c) shows the mesh near the channel bed in a vertical plane cutting through three mussels. The average cell size increases at larger distances from the emerged part of the shell. Based on the channel Reynolds number and the non-dimensional bed friction velocity over a smooth surface, the average cell size in the directions parallel to the surface of the mussel’s shell is approximately 30 wall units close to the mussel. At most locations, the first grid point in the wall normal direction is situated at less than two wall units from the bed and the mussel’s shell.

The bulk velocity in the incoming flow is U0

![]() $=$

0.3 ms−1. The total height of the mussel is d

$=$

0.3 ms−1. The total height of the mussel is d

![]() $=$

0.06 m. The flow depth is D

$=$

0.06 m. The flow depth is D

![]() $=$

0.15 m. These conditions mimic those in the flume laboratory experiments of Sansom et al., (Reference Sansom, Bent, Atkinson and Vaughn2020) conducted with the same species of mussels but with a gravel bed. These experiments were based on conditions observed in Tonowanda Creek and French Creek in New York state, USA. Both rivers contain large mussel populations. The channel Reynolds number, ReD

, is close to 45 000 (table 1), same as that in the single-mussel simulations reported by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Constantinescu and Zeng2020) and Wu & Constantinescu (Reference Wu and Constantinescu2022), and close to the Reynolds numbers in the experiments of Sansom et al. (Reference Sansom, Bent, Atkinson and Vaughn2020). The channel Froude number is close to theat in the two aforementioned rivers at baseflow conditions. In each simulation, the mussels are close to evenly distributed over the entire mussel bed region in a random arrangement (e.g. see figure 1

b). This is a better option than to using a regular staggered arrangement because mussels are not distributed regularly on the riverbed. Preliminary simulations have shown that slightly changing the horizontal positions of the mussels while keeping the mean mussel array density constant has little effect on the overall growth characteristics of the 2-D boundary layer and width-averaged velocity and turbulent kinetic energy profiles.

$=$

0.15 m. These conditions mimic those in the flume laboratory experiments of Sansom et al., (Reference Sansom, Bent, Atkinson and Vaughn2020) conducted with the same species of mussels but with a gravel bed. These experiments were based on conditions observed in Tonowanda Creek and French Creek in New York state, USA. Both rivers contain large mussel populations. The channel Reynolds number, ReD

, is close to 45 000 (table 1), same as that in the single-mussel simulations reported by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Constantinescu and Zeng2020) and Wu & Constantinescu (Reference Wu and Constantinescu2022), and close to the Reynolds numbers in the experiments of Sansom et al. (Reference Sansom, Bent, Atkinson and Vaughn2020). The channel Froude number is close to theat in the two aforementioned rivers at baseflow conditions. In each simulation, the mussels are close to evenly distributed over the entire mussel bed region in a random arrangement (e.g. see figure 1

b). This is a better option than to using a regular staggered arrangement because mussels are not distributed regularly on the riverbed. Preliminary simulations have shown that slightly changing the horizontal positions of the mussels while keeping the mean mussel array density constant has little effect on the overall growth characteristics of the 2-D boundary layer and width-averaged velocity and turbulent kinetic energy profiles.

Table 1. Main flow and geometrical parameters in the simulations of flow past a mussel bed (

![]() $\rho$

N

is the mussel array density, VR

$\rho$

N

is the mussel array density, VR

![]() $=$

Ue

/U0

is momentum filtration ratio, h is the height of the exposed part of the mussel, d is the total mussel height, ReD

$=$

Ue

/U0

is momentum filtration ratio, h is the height of the exposed part of the mussel, d is the total mussel height, ReD

![]() $=$

UoD/

$=$

UoD/

![]() $\nu$

, Reh

$\nu$

, Reh

![]() $=$

U0h/

$=$

U0h/

![]() $\nu$

and

$\nu$

and

![]() $\Delta$

S is the average distance between the mussels,

$\Delta$

S is the average distance between the mussels,

![]() $\nu$

is the molecular viscosity).

$\nu$

is the molecular viscosity).

Simulations are performed with various values of the main three physical parameters that describe the mussel bed configuration, i.e. mussel array density (

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

10, 25, 55, 100 mussels m−2), filtration velocity ratio (VR

$=$

10, 25, 55, 100 mussels m−2), filtration velocity ratio (VR

![]() $=$

0.0, 0.013, 0.13, 0.7) and height of the protruding part of the mussel shell (h

$=$

0.0, 0.013, 0.13, 0.7) and height of the protruding part of the mussel shell (h

![]() $=$

0.3d, 0.5d). Table 1 summarises the matrix of simulations. Table 1 also includes the average distance between the mussels,

$=$

0.3d, 0.5d). Table 1 summarises the matrix of simulations. Table 1 also includes the average distance between the mussels,

![]() $\Delta$

S, and the Reynolds number defined with the protruding height of the mussels, Reh

. Given that D/h

$\Delta$

S, and the Reynolds number defined with the protruding height of the mussels, Reh

. Given that D/h

![]() $\gt$

4 in all simulations, the interactions of the mussels with the free surface are negligible (Shamloo, Rajaratnam & Katopodis Reference Shamloo, Rajaratnam and Katopodis2001). The values of

$\gt$

4 in all simulations, the interactions of the mussels with the free surface are negligible (Shamloo, Rajaratnam & Katopodis Reference Shamloo, Rajaratnam and Katopodis2001). The values of

![]() $\rho$

N

in the present set of simulations represent a reasonable range of mussel densities in naturally populated freshwater mussel communities in rivers (Allen & Vaughn Reference Allen and Vaughn2010; Sansom et al. 2018) and are representative of the mussel bed densities in the Tonowanda Creek and French Creek. For an average mussel height of 0.06 m, the average exposure height of Lampsilis siliquoidea mussels in river beds is 0.03–0.04 m (Sansom et al. Reference Sansom, Bent, Atkinson and Vaughn2020). This is why most of the present simulations are conducted with h

$\rho$

N

in the present set of simulations represent a reasonable range of mussel densities in naturally populated freshwater mussel communities in rivers (Allen & Vaughn Reference Allen and Vaughn2010; Sansom et al. 2018) and are representative of the mussel bed densities in the Tonowanda Creek and French Creek. For an average mussel height of 0.06 m, the average exposure height of Lampsilis siliquoidea mussels in river beds is 0.03–0.04 m (Sansom et al. Reference Sansom, Bent, Atkinson and Vaughn2020). This is why most of the present simulations are conducted with h

![]() $=$

0.5d, corresponding to 50 % exposure level, which is also typical for other species of freshwater mussels (Termini et al. Reference Termini2023). To avoid dislocation due to changing conditions, mussels decrease their exposure level. To characterise such cases, some simulations are conducted with a higher level of mussel burrowing (h

$=$

0.5d, corresponding to 50 % exposure level, which is also typical for other species of freshwater mussels (Termini et al. Reference Termini2023). To avoid dislocation due to changing conditions, mussels decrease their exposure level. To characterise such cases, some simulations are conducted with a higher level of mussel burrowing (h

![]() $=$

0.3d).

$=$

0.3d).

For VR

![]() $=$

0.13, the volumetric filtration flow rate through the two syphons is Qs

$=$

0.13, the volumetric filtration flow rate through the two syphons is Qs

![]() $=$

1.6 × 10−6 m3s−1, which is within the average range for the mussel species (Lampsilis siliquoidea) considered in the study. The volumetric filtration flow rate in the VR

$=$

1.6 × 10−6 m3s−1, which is within the average range for the mussel species (Lampsilis siliquoidea) considered in the study. The volumetric filtration flow rate in the VR

![]() $=$

0.7 simulations is close to the maximum value for unionids (Price & Schiebe Reference Price and Schiebe1978). The aspect ratio h/b is equal to 0.75 in the h/d

$=$

0.7 simulations is close to the maximum value for unionids (Price & Schiebe Reference Price and Schiebe1978). The aspect ratio h/b is equal to 0.75 in the h/d

![]() $=$

0.5 cases and 0.5 in the h/d

$=$

0.5 cases and 0.5 in the h/d

![]() $=$

0.25 cases, where b is the maximum width of the protruding part of the mussel (figure 1

a). The influence of active filtering on the mean flow can be considered to be negligible in the simulations performed with VR ≤ 0.13. This was confirmed by comparing results obtained from

$=$

0.25 cases, where b is the maximum width of the protruding part of the mussel (figure 1

a). The influence of active filtering on the mean flow can be considered to be negligible in the simulations performed with VR ≤ 0.13. This was confirmed by comparing results obtained from

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

25 and 55 simulations conducted with VR

$=$

25 and 55 simulations conducted with VR

![]() $=$

0 and

VR

$=$

0 and

VR

![]() $=$

0.13 (see also § 4). In a good approximation, simulations conducted with VR

$=$

0.13 (see also § 4). In a good approximation, simulations conducted with VR

![]() $=$

0.013 can be considered to be equivalent to cases with no active filtering in terms of the spatial development of the internal, rough-bed boundary layer and its mean velocity field. All simulations listed in table 1 were conducted with a molecular Schmidt number, Sc

$=$

0.013 can be considered to be equivalent to cases with no active filtering in terms of the spatial development of the internal, rough-bed boundary layer and its mean velocity field. All simulations listed in table 1 were conducted with a molecular Schmidt number, Sc

![]() $=$

1 and assuming mussels filter all the phytoplankton entering through their incurrent syphon (filtration rate, F

$=$

1 and assuming mussels filter all the phytoplankton entering through their incurrent syphon (filtration rate, F

![]() $=$

100 %). An additional simulation was conducted with Sc

$=$

100 %). An additional simulation was conducted with Sc

![]() $=$

1000 to understand the effect of varying the molecular Schmidt number on the concentration profiles and the thickness of the concentration boundary layer given that the Schmidt number of the coloured dye (e.g. Rhodamine WT) used in experiments performed with mussel beds (O’Riordan et al. Reference O’Riordan, Monismith and Koseff1993) and of the solutes in the mussel system is O(1000). Finally, a simulation was conducted without using the inverse concentration approach to confirm the use of this approach is fully equivalent to that in which the passive scalar tracks the phytoplankton concentration rather that the phytoplankton deficit.

$=$

1000 to understand the effect of varying the molecular Schmidt number on the concentration profiles and the thickness of the concentration boundary layer given that the Schmidt number of the coloured dye (e.g. Rhodamine WT) used in experiments performed with mussel beds (O’Riordan et al. Reference O’Riordan, Monismith and Koseff1993) and of the solutes in the mussel system is O(1000). Finally, a simulation was conducted without using the inverse concentration approach to confirm the use of this approach is fully equivalent to that in which the passive scalar tracks the phytoplankton concentration rather that the phytoplankton deficit.

The boundary conditions are basically the same as those used by Wu et al. (Reference Wu, Constantinescu and Zeng2020) except for the lateral boundaries which are treated as periodic boundaries. The channel bed and the protruding part of each mussel are treated as no-slip, smooth walls on which the modified eddy viscosity is set to zero. The pressure at all boundaries is extrapolated from the interior of the domain. The free surface is treated as a slip (shear-free) rigid lid boundary which is justified given that the channel Froude number is less than 0.3 and D/h

![]() $\gt$

4. As in simulations where the free surface is not deformable, the pressure field is defined up to a constant and a zero pressure is assigned to a point in the inlet section. Given that an unsteady, non-uniform pressure distribution is predicted on the free surface, the treatment of the top boundary accounts in an approximate way for the effects of the roughness elements and turbulent flow eddies on the free surface. A zero-gradient condition is imposed at the outlet section for all variables. The mean velocity, Ue

, is specified at the excurrent-syphon pipe inlet. The discharge Qs

is specified on the surface corresponding to the incurrent syphon. The velocity flow fields specified at the inlet section are obtained from a precursor simulation of fully developed flow in a straight channel of depth D and width B with mean flow velocity U0

. In all but one simulation, the concentration of the passive scalar at the inlet section of the excurrent-syphon pipe of each mussel was Ce

$\gt$

4. As in simulations where the free surface is not deformable, the pressure field is defined up to a constant and a zero pressure is assigned to a point in the inlet section. Given that an unsteady, non-uniform pressure distribution is predicted on the free surface, the treatment of the top boundary accounts in an approximate way for the effects of the roughness elements and turbulent flow eddies on the free surface. A zero-gradient condition is imposed at the outlet section for all variables. The mean velocity, Ue

, is specified at the excurrent-syphon pipe inlet. The discharge Qs

is specified on the surface corresponding to the incurrent syphon. The velocity flow fields specified at the inlet section are obtained from a precursor simulation of fully developed flow in a straight channel of depth D and width B with mean flow velocity U0

. In all but one simulation, the concentration of the passive scalar at the inlet section of the excurrent-syphon pipe of each mussel was Ce

![]() $=$

C0

(no phytoplankton present, phytoplankton filtration rate, F

$=$

C0

(no phytoplankton present, phytoplankton filtration rate, F

![]() $=$

100 %). Additionally, one simulation was performed by assuming that only 80 % of the phytoplankton entering the mussel through the incurrent syphon is filtered (F

$=$

100 %). Additionally, one simulation was performed by assuming that only 80 % of the phytoplankton entering the mussel through the incurrent syphon is filtered (F

![]() $=$

80 %), such that Ce

is a function of the concentration of the flow entering the incurrent syphon, Ci

. The concentration C is set equal to zero at the inlet boundary of the computational domain (e.g. open channel inlet). The gradient of C in the direction perpendicular to the surface is set equal to zero at the free surface, at the other smooth-wall surfaces and at the incurrent syphons. The water entering the incurrent syphon is generally characterised by a non-zero value of the scalar concentration because some of the filtered water by the upstream mussels is advected through the incurrent-syphon flow. So, the concentration of the flow entering the incurrent syphon, Ci

, of each mussel is determined by the numerical solution and is a function of time and the rank of the mussel in the array. As such, the numerical model accounts for partial re-entrainment of excurrent-syphon flows by the incurrent syphons of downstream mussels. This allows studying in a realistic way phytoplankton removal over the mussel bed (see § 6). Finally, in the simulation conducted without using the inverse concentration approach, the boundary conditions was formulated in terms of the concentration of phytoplankton, C’, with C’

$=$

80 %), such that Ce

is a function of the concentration of the flow entering the incurrent syphon, Ci

. The concentration C is set equal to zero at the inlet boundary of the computational domain (e.g. open channel inlet). The gradient of C in the direction perpendicular to the surface is set equal to zero at the free surface, at the other smooth-wall surfaces and at the incurrent syphons. The water entering the incurrent syphon is generally characterised by a non-zero value of the scalar concentration because some of the filtered water by the upstream mussels is advected through the incurrent-syphon flow. So, the concentration of the flow entering the incurrent syphon, Ci

, of each mussel is determined by the numerical solution and is a function of time and the rank of the mussel in the array. As such, the numerical model accounts for partial re-entrainment of excurrent-syphon flows by the incurrent syphons of downstream mussels. This allows studying in a realistic way phytoplankton removal over the mussel bed (see § 6). Finally, in the simulation conducted without using the inverse concentration approach, the boundary conditions was formulated in terms of the concentration of phytoplankton, C’, with C’

![]() $=$

C0

at the inlet section of the computational domain and C’

$=$

C0

at the inlet section of the computational domain and C’

![]() $=$

0 (100 % filtration of the phytoplankton entering the incurrent syphon) at the excurrent syphon of each mussel. The value of C’ at the incurrent syphons was determined by the numerical solution based on the phytoplankton concentration of the fluid entrained into each syphon.

$=$

0 (100 % filtration of the phytoplankton entering the incurrent syphon) at the excurrent syphon of each mussel. The value of C’ at the incurrent syphons was determined by the numerical solution based on the phytoplankton concentration of the fluid entrained into each syphon.

3. Two-dimensional boundary layer over the mussel bed

3.1. General features of the distributions of the double-averaged variables over the mussel bed

Downstream of the location (x/d

![]() $=$

x/h

$=$

x/h

![]() $=$

0) where the mussel bed starts, most of the drag is due to form drag associated with the pressure force imbalance on the upstream and downstream faces of the protruding part of the shell. The pressure increase is the largest on the frontal part of the shells where strong adverse pressure gradients are generated as the approaching flow is diverted along the two sides and top of the shell (e.g. see mean pressure distribution Pmean

in figure 2(b) for the

$=$

0) where the mussel bed starts, most of the drag is due to form drag associated with the pressure force imbalance on the upstream and downstream faces of the protruding part of the shell. The pressure increase is the largest on the frontal part of the shells where strong adverse pressure gradients are generated as the approaching flow is diverted along the two sides and top of the shell (e.g. see mean pressure distribution Pmean

in figure 2(b) for the

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

100 mussels m−2, VR

$=$

100 mussels m−2, VR

![]() $=$

0.13, h/d

$=$

0.13, h/d

![]() $=$

0.5 case). These large local variations of the pressure acting on the protruding part of each shell are accompanied by a large rate of streamwise decay of the mean pressure in the open channel (figure 2

a), which is much larger than the rate of decay recorded in the case of a fully developed open channel over a smooth bed where friction drag is the only contributor to the total drag at the bed, assuming the discharge is the same. Due to the additional drag acting on the lower layer of fluid, the mean streamwise velocity reduces in between the bed and the top of the mussels (z

$=$

0.5 case). These large local variations of the pressure acting on the protruding part of each shell are accompanied by a large rate of streamwise decay of the mean pressure in the open channel (figure 2

a), which is much larger than the rate of decay recorded in the case of a fully developed open channel over a smooth bed where friction drag is the only contributor to the total drag at the bed, assuming the discharge is the same. Due to the additional drag acting on the lower layer of fluid, the mean streamwise velocity reduces in between the bed and the top of the mussels (z

![]() $=$

h) with respect to the velocity distribution in the corresponding fully developed open channel flow over a smooth bed. The interactions of the incoming flow with the protruding parts of the shells and with the excurrent-syphon jets generate large-scale turbulence and shedding behind the shells which amplifies the turbulent kinetic energy away from the channel bed. This is why, for sufficiently high

$=$

h) with respect to the velocity distribution in the corresponding fully developed open channel flow over a smooth bed. The interactions of the incoming flow with the protruding parts of the shells and with the excurrent-syphon jets generate large-scale turbulence and shedding behind the shells which amplifies the turbulent kinetic energy away from the channel bed. This is why, for sufficiently high

![]() $\rho$

N

, the maximum turbulent kinetic energy is not recorded in the immediate vicinity of the bed surface, as occurs in the corresponding case of fully developed flow over a smooth bed, but rather close to z

$\rho$

N

, the maximum turbulent kinetic energy is not recorded in the immediate vicinity of the bed surface, as occurs in the corresponding case of fully developed flow over a smooth bed, but rather close to z

![]() $=$

h (see double averaged profiles in figure 3

c).

$=$

h (see double averaged profiles in figure 3

c).

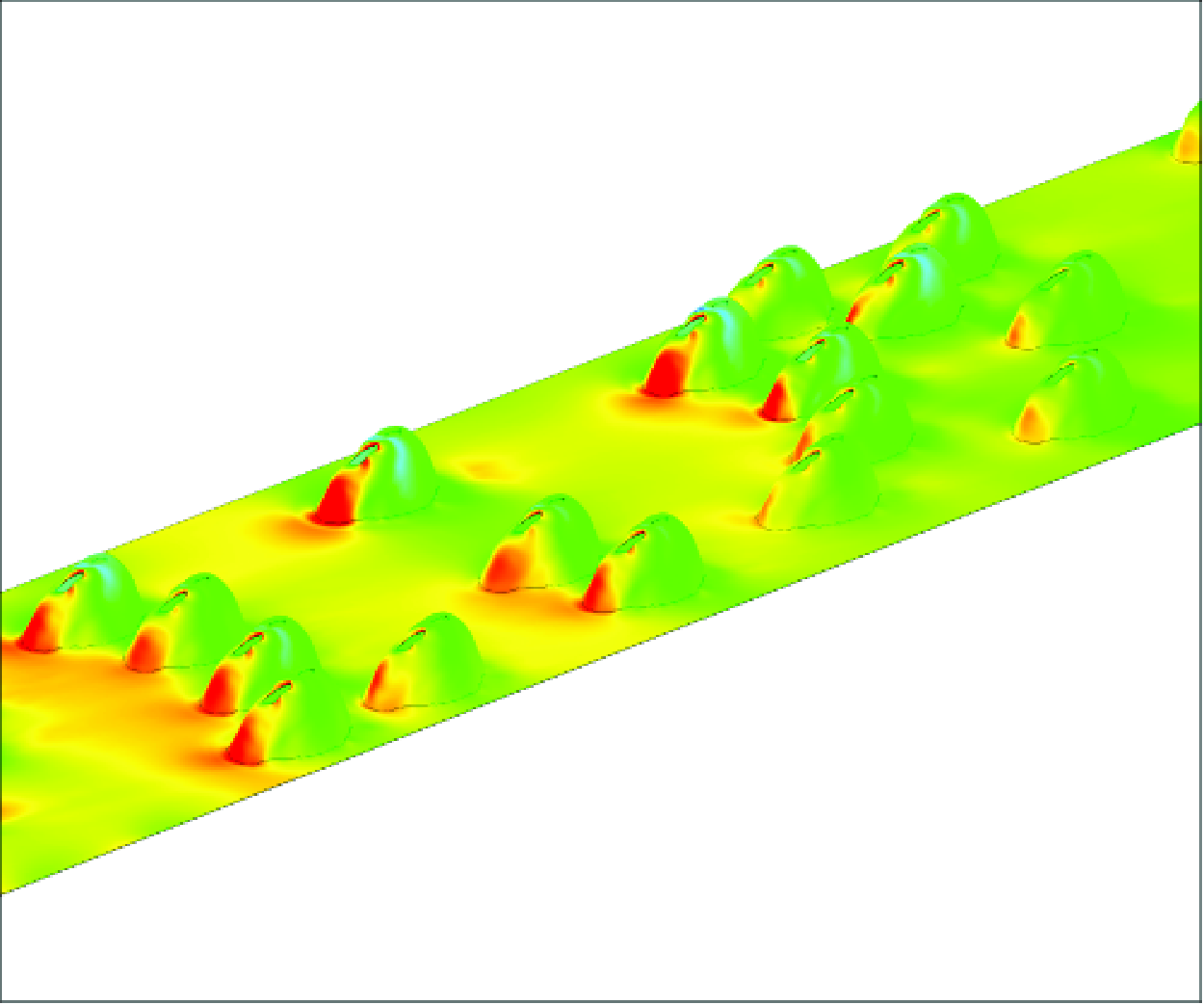

Figure 2. General features of the mean flow fields in the numerical solutions with

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

100 mussels m−2 and h/d

$=$

100 mussels m−2 and h/d

![]() $=$

0.5 case: (a) general view showing overall streamwise decay of the mean pressure Pmean

/(

$=$

0.5 case: (a) general view showing overall streamwise decay of the mean pressure Pmean

/(

![]() $\rho$

U0

2) over the channel bed due to the added drag by the mussels (VR

$\rho$

U0

2) over the channel bed due to the added drag by the mussels (VR

![]() $=$

0.13); (b) detail view showing mean pressure distributions on the protruding parts of the partially burrowed mussels situated near the leading edge of the mussel bed (VR

$=$

0.13); (b) detail view showing mean pressure distributions on the protruding parts of the partially burrowed mussels situated near the leading edge of the mussel bed (VR

![]() $=$

0.13); (c) detail view showing the mean scalar concentration, C/C0

, in a vertical-streamwise plane (y/d

$=$

0.13); (c) detail view showing the mean scalar concentration, C/C0

, in a vertical-streamwise plane (y/d

![]() $=$

3.3) cutting through several mussels (VR

$=$

3.3) cutting through several mussels (VR

![]() $=$

0.7) and 2-D streamlines visualising the curving of the excurrent-syphon jet; (d) detail view showing the mean spanwise vorticity,

$=$

0.7) and 2-D streamlines visualising the curving of the excurrent-syphon jet; (d) detail view showing the mean spanwise vorticity,

![]() $\omega$

yd/U0

, in a vertical-streamwise plane (y/d

$\omega$

yd/U0

, in a vertical-streamwise plane (y/d

![]() $=$

3.3) cutting through several mussels (VR

$=$

3.3) cutting through several mussels (VR

![]() $=$

0.7) and 2-D streamlines.

$=$

0.7) and 2-D streamlines.

Figure 3. Spatial evolution of the streamwise velocity, scalar concentration and turbulent kinetic energy inside the 2-D boundary layer in the

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

100 mussel m−2, VR

$=$

100 mussel m−2, VR

![]() $=$

0.13, h/d

$=$

0.13, h/d

![]() $=$

0.5 case: (a) vertical profiles of streamwise velocity, Uxz

/U0

; (b) vertical profiles of scalar concentration, Cxz

/C0

for Sc

$=$

0.5 case: (a) vertical profiles of streamwise velocity, Uxz

/U0

; (b) vertical profiles of scalar concentration, Cxz

/C0

for Sc

![]() $=$

1; (c) vertical profiles of turbulent kinetic energy, Kxz

/U0

2. The vertical arrow denotes the leading edge of the mussel bed (x/h

$=$

1; (c) vertical profiles of turbulent kinetic energy, Kxz

/U0

2. The vertical arrow denotes the leading edge of the mussel bed (x/h

![]() $=$

0). The horizontal dashed lines show the locations where z

$=$

0). The horizontal dashed lines show the locations where z

![]() $= \delta(x)$

. Panel (d) shows the effect of Schmidt number on the Cxz

/C0

profiles at x/h

$= \delta(x)$

. Panel (d) shows the effect of Schmidt number on the Cxz

/C0

profiles at x/h

![]() $=$

90, 130 and 190 based on simulations conducted with Sc

$=$

90, 130 and 190 based on simulations conducted with Sc

![]() $=$

1 and Sc

$=$

1 and Sc

![]() $=$

1000. Panel (e) compares the non-dimensional concentration profiles at x/h

$=$

1000. Panel (e) compares the non-dimensional concentration profiles at x/h

![]() $=$

100 and x/h

$=$

100 and x/h

![]() $=$

130 for Sc

$=$

130 for Sc

![]() $=$

1. The profiles are calculated using the inverse concentration approach and using the physical boundary conditions where the phytoplankton concentration of the incoming flow in the open channel is C’

$=$

1. The profiles are calculated using the inverse concentration approach and using the physical boundary conditions where the phytoplankton concentration of the incoming flow in the open channel is C’

![]() $=$

C0

and the concentration of the fluid entering the channel through the excurrent syphon is Ce’

$=$

C0

and the concentration of the fluid entering the channel through the excurrent syphon is Ce’

![]() $=$

0 (filtration rate, F

$=$

0 (filtration rate, F

![]() $=$

100 %). Results are also included for a simulation where mussels filter only 80 % of the amount of phytoplankton entering each mussel through the incurrent syphon (F

$=$

100 %). Results are also included for a simulation where mussels filter only 80 % of the amount of phytoplankton entering each mussel through the incurrent syphon (F

![]() $=$

80 %).

$=$

80 %).

Figure 2(c) shows the distribution of the time-averaged scalar concentration in a vertical-streamwise plane cutting through the excurrent syphons of two of the mussels in the array. They show how the jets of filtered water mix with the surrounding fluid. Most of the dilution occurs within 2–3h downstream of the incurrent syphon. The region shown in figure 2(c) is situated in the downstream part of the array where the concentration boundary layer already reached the top boundary. The mean concentration increases monotonically with the distance from the top boundary within most of the inertial layer except for the region of high concentration associated with the excurrent-syphon jets. The mean spanwise vorticity contours in figure 2(d) show that even for the highest filtering discharge (e.g. for VR

![]() $=$

0.7), the vertical penetration of the excurrent jet is less than 0.3d before the jet becomes more or less aligned with the streamwise direction. This is followed by a regime where the centreline of the diluted jet moves slightly away from the bottom surface as it is advected downstream.

$=$

0.7), the vertical penetration of the excurrent jet is less than 0.3d before the jet becomes more or less aligned with the streamwise direction. This is followed by a regime where the centreline of the diluted jet moves slightly away from the bottom surface as it is advected downstream.

Given the strong three-dimensional characteristics of the flow around the protruding shells, these effects are more easily studied and quantified using double-averaging, which is a technique widely employed to study flow past rough surfaces, including flow past large-scale bed roughness elements and flow over porous layers (e.g. see Nikora et al. Reference Nikora, McEwan, McLean, Coleman, Pokrajac and Walters2007; Coleman et al. Reference Coleman, Nikora, McLean and Schlicke2007). The averaging is performed along the spanwise direction in addition to averaging over time the instantaneous flow variables. The following formula is used to compute the width-averaged, mean streamwise velocity, Uxz :

where B’(x,z) is the total width of the region occupied by the fluid (e.g. the interior of the protruding part of each shell is excluded). For z

![]() $\gt$

h, B’(x,z)

$\gt$

h, B’(x,z)

![]() $=$

B and (3.1) reduces to calculating the standard width-averaged value of the time-averaged 3-D velocity U(x,y,z). The

$=$

B and (3.1) reduces to calculating the standard width-averaged value of the time-averaged 3-D velocity U(x,y,z). The

![]() $\lt$

$\lt$

![]() $\gt$

operator denotes width-averaging of a time-averaged variable. A similar procedure is used to calculate the width-averaged mean scalar concentration, Cxz

, the width-averaged turbulent kinetic energy, Kxz

, and the width-averaged turbulent and dispersive stresses. Before discussing the profiles of Uxz

, Cxz

and Kxz

, we compared the double-averaged profiles of the velocity, concentration and TKE obtained using the 3-D mean flow fields over the full domain width and over half of the domain width for the

$\gt$

operator denotes width-averaging of a time-averaged variable. A similar procedure is used to calculate the width-averaged mean scalar concentration, Cxz

, the width-averaged turbulent kinetic energy, Kxz

, and the width-averaged turbulent and dispersive stresses. Before discussing the profiles of Uxz

, Cxz

and Kxz

, we compared the double-averaged profiles of the velocity, concentration and TKE obtained using the 3-D mean flow fields over the full domain width and over half of the domain width for the

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

100 mussel m−2, VR

$=$

100 mussel m−2, VR

![]() $=$

0.13, h/d

$=$

0.13, h/d

![]() $=$

0.5 case. The two sets of double-averaged profiles were found to be very close, which means that the domain width was large enough such that the characteristics of the double-averaged rough-bed boundary layer are basically independent of the domain width.

$=$

0.5 case. The two sets of double-averaged profiles were found to be very close, which means that the domain width was large enough such that the characteristics of the double-averaged rough-bed boundary layer are basically independent of the domain width.

The vertical profiles of Uxz

, Cxz

and Kxz

are shown in figures 3(a)–3(c) for the

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

100 mussel m−2, VR

$=$

100 mussel m−2, VR

![]() $=$

0.13, h/d

$=$

0.13, h/d

![]() $=$

0.5 case. The shape of the velocity profile changes quickly as the incoming (smooth-bed) fully developed flow (e.g. see profile at x/h

$=$

0.5 case. The shape of the velocity profile changes quickly as the incoming (smooth-bed) fully developed flow (e.g. see profile at x/h

![]() $=$

-10 in figure 3

a) moves over the region (x/h

$=$

-10 in figure 3

a) moves over the region (x/h

![]() $\gt$

0) containing mussels. A sudden decrease in the rate of increase of the streamwise velocity is observed in the velocity profiles between x/h

$\gt$

0) containing mussels. A sudden decrease in the rate of increase of the streamwise velocity is observed in the velocity profiles between x/h

![]() $=$

0 and x/h

$=$

0 and x/h

![]() $=$

120. As will be discussed later, the vertical location at which the sudden decrease starts corresponds to the top of the rough-bed boundary layer. The peak value of the scalar concentration profiles over the mussel bed is observed around the vertical location of the excurrent syphons (z/h ≈ 1, figure 3

b). Above this location, Cxz

decays monotonically towards zero, a value reached at the top of the concentration boundary layer. Past the location of the leading edge of the mussel bed, the vertical profiles and mean levels of the turbulent kinetic energy (figure 3

c) are very different from that in the incoming flow. A sharp amplification of more than five times with respect to the peak values in the approaching flow is observed for Kxz

starting a short distance downstream of the leading edge of the mussel bed (e.g. compare profile at x/h

$=$

120. As will be discussed later, the vertical location at which the sudden decrease starts corresponds to the top of the rough-bed boundary layer. The peak value of the scalar concentration profiles over the mussel bed is observed around the vertical location of the excurrent syphons (z/h ≈ 1, figure 3

b). Above this location, Cxz

decays monotonically towards zero, a value reached at the top of the concentration boundary layer. Past the location of the leading edge of the mussel bed, the vertical profiles and mean levels of the turbulent kinetic energy (figure 3

c) are very different from that in the incoming flow. A sharp amplification of more than five times with respect to the peak values in the approaching flow is observed for Kxz

starting a short distance downstream of the leading edge of the mussel bed (e.g. compare profile at x/h

![]() $=$

-10 with profiles at x/h

$=$

-10 with profiles at x/h

![]() $\gt$

10 in figure 3

c). These large values are induced by the eddies (e.g. vortex tubes) shed in the separated shear layers generated by the mussels situated close to the leading edge of the mussel bed. The region of high Kxz

occupies the entire roughness layer (0 ≤ z ≤ h) and its height over the top of the mussels increases monotonically in the streamwise direction. The Kxz

profiles in figure 3(c) suggest that the rough-bed boundary layer reaches the free surface before the trailing edge of the mussel bed (x/h

$\gt$

10 in figure 3

c). These large values are induced by the eddies (e.g. vortex tubes) shed in the separated shear layers generated by the mussels situated close to the leading edge of the mussel bed. The region of high Kxz

occupies the entire roughness layer (0 ≤ z ≤ h) and its height over the top of the mussels increases monotonically in the streamwise direction. The Kxz

profiles in figure 3(c) suggest that the rough-bed boundary layer reaches the free surface before the trailing edge of the mussel bed (x/h

![]() $=$

200). Non-zero values of the scalar concentration at the free surface are also observed for Cxz

starting around x/h

$=$

200). Non-zero values of the scalar concentration at the free surface are also observed for Cxz

starting around x/h

![]() $=$

120 (figure 3

b). Given that the incoming flow contains no scalar, the rough-bed boundary layer reaches the free surface before the end of the mussel bed.

$=$

120 (figure 3

b). Given that the incoming flow contains no scalar, the rough-bed boundary layer reaches the free surface before the end of the mussel bed.

Figure 3(d) investigates the Schmidt number effect on the concentration boundary layer for a mussel bed with

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

100 mussel m−2, VR

$=$

100 mussel m−2, VR

![]() $=$

0.13 and h/d

$=$

0.13 and h/d

![]() $=$

0.5 by comparing the double-averaged concentration profiles obtained from two simulations conducted with Sc

$=$

0.5 by comparing the double-averaged concentration profiles obtained from two simulations conducted with Sc

![]() $=$

1 and Sc

$=$

1 and Sc

![]() $=$

1000. As the dynamics of the phytoplankton concentration is simulated using a passive scalar equation, the velocity fields and the double-averaged profiles of the velocity and turbulent kinetic energy are not affected by the value of the Schmidt number. The same is true for the thickness of the boundary layer based on the vertical profiles of Kxz

. As opposed to a concentration boundary layer developing over a smooth bed, where the value of the Schmidt number can significantly affect the growth rate of the boundary layer, results in figure 3(d) show this is not the case for the boundary layer developing over the mussel bed. In particular, the effect of increasing the Schmidt number from 1 to 1000 is negligible inside the inertial layer, so

$=$

1000. As the dynamics of the phytoplankton concentration is simulated using a passive scalar equation, the velocity fields and the double-averaged profiles of the velocity and turbulent kinetic energy are not affected by the value of the Schmidt number. The same is true for the thickness of the boundary layer based on the vertical profiles of Kxz

. As opposed to a concentration boundary layer developing over a smooth bed, where the value of the Schmidt number can significantly affect the growth rate of the boundary layer, results in figure 3(d) show this is not the case for the boundary layer developing over the mussel bed. In particular, the effect of increasing the Schmidt number from 1 to 1000 is negligible inside the inertial layer, so

![]() $\delta$

C

is basically independent of the Schmidt number over this interval. Some mild Schmidt number effects are present inside the inner layer. The main reason is that mixing between the filtered water and the phytoplankton-rich water is driven, to a large extent, by the larger-scale turbulent eddies generated by the emerged parts of the mussel shells (e.g. see Wu et al. Reference Wu, Constantinescu and Zeng2020 for a detailed discussion of the coherent structures generated by individual partially burrowed mussels). The main eddies are the vortex tubes generated in the separated shear layers and large-scale hairpins that scale with the height of the protruding part of the mussels. The size and dynamics of these eddies are independent of the value of the Schmidt number. This is the main reason why analysis performed based on simulations conducted with Sc

$\delta$

C

is basically independent of the Schmidt number over this interval. Some mild Schmidt number effects are present inside the inner layer. The main reason is that mixing between the filtered water and the phytoplankton-rich water is driven, to a large extent, by the larger-scale turbulent eddies generated by the emerged parts of the mussel shells (e.g. see Wu et al. Reference Wu, Constantinescu and Zeng2020 for a detailed discussion of the coherent structures generated by individual partially burrowed mussels). The main eddies are the vortex tubes generated in the separated shear layers and large-scale hairpins that scale with the height of the protruding part of the mussels. The size and dynamics of these eddies are independent of the value of the Schmidt number. This is the main reason why analysis performed based on simulations conducted with Sc

![]() $=$

1 is also fairly representative of a much larger range of Schmidt numbers for the concentration boundary layer generated by the partially burrowed mussels.

$=$

1 is also fairly representative of a much larger range of Schmidt numbers for the concentration boundary layer generated by the partially burrowed mussels.

Given that the velocity fields are not affected by the use of the inverse concentration approach and that the relationship between the phytoplankton concentration, C’, and the concentration C used in the inverse concentration approach is linear (i.e. C

![]() $=$

C0

- C’), the predicted distributions of C’ and C’xz

(or, equivalently, of C

0

- C’ and C

0

- C’xz

) should be fully equivalent to those obtained using the inverse concentration approach. This is confirmed by results of two simulations (Sc

$=$

C0

- C’), the predicted distributions of C’ and C’xz

(or, equivalently, of C

0

- C’ and C

0

- C’xz

) should be fully equivalent to those obtained using the inverse concentration approach. This is confirmed by results of two simulations (Sc

![]() $=$

1, F

$=$

1, F

![]() $=$

100 %) of the

$=$

100 %) of the

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

100 mussel m−2, VR

$=$

100 mussel m−2, VR

![]() $=$

0.13, h/d

$=$

0.13, h/d

![]() $=$

0.5 case conducted with and without the inverse concentration approach. For example, figure 3(e) shows that the profiles of 1 - C’xz

/C0

and Cxz

/C0

from two simulations in which the scalar transport equation is solved for C’ and respectively for C are identical at x/h

$=$

0.5 case conducted with and without the inverse concentration approach. For example, figure 3(e) shows that the profiles of 1 - C’xz

/C0

and Cxz

/C0

from two simulations in which the scalar transport equation is solved for C’ and respectively for C are identical at x/h

![]() $=$

100 and x/h

$=$

100 and x/h

![]() $=$

130.

$=$

130.

Even though in most models it is generally assumed that mussels filter all the phytoplankton entering through their incurrent syphon (F

![]() $=$

100 %), it is possible that not all plankton is filtered by these organisms (F

$=$

100 %), it is possible that not all plankton is filtered by these organisms (F

![]() $\lt$

100 %). Figure 3(e) compares the profiles of Cxz

/C0

from two simulations of the

$\lt$

100 %). Figure 3(e) compares the profiles of Cxz

/C0

from two simulations of the

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

100 mussel m−2, VR

$=$

100 mussel m−2, VR

![]() $=$

0.13, h/d

$=$

0.13, h/d

![]() $=$

0.5 case performed with F

$=$

0.5 case performed with F

![]() $=$

100 % and F

$=$

100 % and F

![]() $=$

80 %. As expected, the values of Cxz

/C0

predicted in the F

$=$

80 %. As expected, the values of Cxz

/C0

predicted in the F

![]() $=$

80 % simulation are smaller. However, if the profiles in the F

$=$

80 % simulation are smaller. However, if the profiles in the F

![]() $=$

80 % simulation are rescaled using the maximum concentration, which is very close to the excurrent syphon concentration, the profiles in the F

$=$

80 % simulation are rescaled using the maximum concentration, which is very close to the excurrent syphon concentration, the profiles in the F

![]() $=$

80 % simulation become close to identical to those predicted in the F

$=$

80 % simulation become close to identical to those predicted in the F

![]() $=$

100 % simulation. This shows that results from the present study can also be used to make predictions for cases where the mussel filtration rate is less than 100 %.

$=$

100 % simulation. This shows that results from the present study can also be used to make predictions for cases where the mussel filtration rate is less than 100 %.

Figure 4 compares the streamwise distributions of the peak values of the vertical profiles of Cxz

and Kxz

in the simulations performed with Sc

![]() $=$

1 and F

$=$

1 and F

![]() $=$

100 %. These peak values are denoted Cmax

and Kmax

, respectively. While the streamwise growth of Cmax

is a direct consequence of the increase in the number of jets entering the domain with increasing x/h, the streamwise increase of Kmax

is because energetic coherent structures passing through a certain cross-section are generated by all the mussels situated in between the leading edge of the mussel bed and that section. For constant VR and h/d, Cmax

and Kmax

increase monotonically with

$=$

100 %. These peak values are denoted Cmax

and Kmax

, respectively. While the streamwise growth of Cmax

is a direct consequence of the increase in the number of jets entering the domain with increasing x/h, the streamwise increase of Kmax

is because energetic coherent structures passing through a certain cross-section are generated by all the mussels situated in between the leading edge of the mussel bed and that section. For constant VR and h/d, Cmax

and Kmax

increase monotonically with

![]() $\rho$

N

, which is expected given that the bed contains more mussels per unit streamwise length (figure 4

a). Moreover, the average streamwise rate of growth of Cmax

also increases with

$\rho$

N

, which is expected given that the bed contains more mussels per unit streamwise length (figure 4

a). Moreover, the average streamwise rate of growth of Cmax

also increases with

![]() $\rho$

N. Given that most of the large-scale coherent structures generated by mussels scale with the height of their protruding part, it is not surprising to see a decrease of 30 %–45 % for Kmax

as h/d decreases from 0.5 to 0.3 in the simulations with

$\rho$

N. Given that most of the large-scale coherent structures generated by mussels scale with the height of their protruding part, it is not surprising to see a decrease of 30 %–45 % for Kmax

as h/d decreases from 0.5 to 0.3 in the simulations with

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

100 mussels m−2 and VR

$=$

100 mussels m−2 and VR

![]() $=$

0.13 (figure 4

b). However, the effect of decreasing h/d on Cmax

is negligible. For constant

$=$

0.13 (figure 4

b). However, the effect of decreasing h/d on Cmax

is negligible. For constant

![]() $\rho$

N

and h/d, Kmax

increases with increasing the filtering discharge due to the increased momentum of the excurrent jets (figure 4

c). The rate of increase of Kmax

with VR decreases above medium values (e.g. VR ≥ 0.13) of the filtering discharge.

$\rho$

N

and h/d, Kmax

increases with increasing the filtering discharge due to the increased momentum of the excurrent jets (figure 4

c). The rate of increase of Kmax

with VR decreases above medium values (e.g. VR ≥ 0.13) of the filtering discharge.

Figure 4. Streamwise variation of the peak scalar concentration and turbulent kinetic energy inside the rough-bed turbulent boundary layer: (a) Cmax

/C0

and Kmax

/U0

2 versus

![]() $\rho$

N

for VR

$\rho$

N

for VR

![]() $=$

0.13, h/d

$=$

0.13, h/d

![]() $=$

0.5; (b) Cmax

/C0

and Kmax

/U0

2 versus h/d for

$=$

0.5; (b) Cmax

/C0

and Kmax

/U0

2 versus h/d for

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

100 mussels m−2, VR

$=$

100 mussels m−2, VR

![]() $=$

0.13; (c) Kmax

/U0

2 versus VR for

$=$

0.13; (c) Kmax

/U0

2 versus VR for

![]() $\rho$

N

$\rho$

N

![]() $=$

100 mussels m−2, h/d

$=$

100 mussels m−2, h/d

![]() $=$

0.5.

$=$

0.5.

The vertical positions corresponding to the peak values in the vertical profiles of Cxz

and Kxz

are denoted zC

and zK