At the beginning of the nineteenth century, several large private collections of music were donated to, or acquired by, the recently created Sing-Akademie zu Berlin.Footnote 1 Of these, one of the largest was that of amateur musician and latterly co-director of the Berlin Royal Porcelain Factory, Carl Jacob Christian Klipfel (1727–1802).Footnote 2 Unknown prior to the restoration of the Sing-Akademie materials to Berlin in 2000, this remarkable collection of over 520 items (amounting to over 10% of the entire Sing-Akademie collection) is significant for a variety of reasons: the relative completeness of the surviving portion of Klipfel's collection provides an unusually detailed, and possibly quite unique, representation of the repertoire of an eighteenth-century collegium musicum and of an organization in Meissen that, hitherto, has not been recognised or researched; the Klipfel collection preserves unica copies of works by a large number of Dresden and other Saxon composers, and in particular, the music of Johann Christian Roellig (b.1716); it provides a great deal of light on the principally instrumental repertoire performed by provincial and amateur musical bodies in the mid-eighteenth century, as well as indicating how the music of Dresden Kapellmeister Hasse was disseminated outside the court. It also demonstrates the importance of city-to-city distribution of musical works in contrast to the more familiar court-to-court transmission in the eighteenth century. Finally, a study of the handwriting of the principal copyist (Klipfel himself) makes it possible to date works within the collection more accurately.

Klipfel's materials were amalgamated and mixed with items from other collections that were acquired by the Sing-Akademie during the early nineteenth century. Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758–1832) created the first catalogue of the holdings (the ‘Zelter’ numbers), but although a more systematic catalogue was contemplated in the early twentieth century, it was not completed prior to World War II. For its protection during the hostilities, the collection was moved to Silesia. Here, it was discovered by advancing Soviet Army forces and transported to Kiev as war trophy, its existence kept secret not only from the West but, due to enmity between Kiev and Moscow, also from the authorities in Moscow. It was kept initially at the P.I. Tchaikovsky Kiev State Conservatoire until 1973, when it was transferred to a secret location.Footnote 3 At some point after 1945 every item in the collection was assigned a new shelf number by the Kiev librarians (the ‘SA’ numbers that are now used) further splitting up items that had previously been listed together. Scores of some works have been separated from sets of parts for the same piece and stored on different shelves, often by genre and in alphabetical order within a sequence of shelfmarks. The survival of the Sing-Akademie collection was only formally acknowledged by the Ukrainian authorities in the late 1990s and the collection was returned by the Ukrainian Government to Berlin in the year 2000.Footnote 4 Almost immediately the first modern catalogue of the holdings was commenced under the direction of Matthias Kornemann and Axel Fischer, completed only in 2008.

Unlike most large collections that survive from eighteenth-century Germany, the Klipfel collection was not created by a professional musician or member of the aristocracy. Neither does it represent the holdings of an institution, but was assembled by an amateur musician. Perhaps only the collections of Johann Heinrich Grave (c.1750–1810),Footnote 5 and of Sara Levy (née Itzig) (1761–1854),Footnote 6 are comparable in Germany, though Klipfel's collection pre-dates these by 30 to 60 years. In the same way that J.S. Bach's personal collection must have provided repertoire for the Leipzig Collegium Musicum, the greater part of Klipfel's collection was assembled to furnish the performing material for the Collegium Musicum in Meissen, a provincial cathedral town on the River Elbe some 30 miles north-east of Dresden. Meissen was also the location of the famed Porcelain Factory owned by the Elector of Saxony that had been established at the beginning of the eighteenth century. Other than the artistic creations of the factory itself, little has been known of the general cultural life of the town and, until this study, nothing of the music-making there.

The ‘Meissen Porcelain Factory Collegium Musicum’ conforms to the model common in the German-speaking areas of an amateur or semi-professional society that met regularly for usually informal music making, as described by Johann Heinrich Zedler (1739) as ‘a gathering of certain musical connoisseurs who, for the benefit of their own exercise in both vocal and instrumental music and under the guidance of a certain director, get together on particular days and in particular locations and perform musical pieces’.Footnote 7 While there are similarities between the function and activity of the Meissen group and its more eminent counterparts in Frankfurt, Hamburg and Leipzig, which were controlled by some of the most important composers of the eighteenth century, there were also quite marked differences, particularly so with the groups in Leipzig, which are the best documented. The discussion that follows is included to provide a context for the Meissen group, highlighting the contrasts between a major university city and a provincial town.

The two collegia musica in Leipzig were founded by Telemann (in 1701) and J.F. Fasch (in 1710). From 1705 Telemann's group had been run in turn by Melchior Hofmann (until 1715), Johann Gottfried Vogler (until c.1718, when he took charge of the group founded by Fasch) and by the organist of the Neukirche, Georg Balthasar Schott, until his appointment as Cantor in Gotha in 1729. From this point the ‘Schottische’ Collegium Musicum was taken over by J.S. Bach and immediately renamed the ‘Bachsische’ Collegium Musicum. Bach relinquished control of the group to C.G. Gerlach after 1741. However, the situation in Leipzig changed after 1743 following the institution of the Grosse Concert (Grand Concerts) by 16 leading merchants, which gave regular concerts to audiences of several hundred. Not only did the new organisation attract the best players from both the academic collegia musica, but Gerlach himself was also involved with its activities. As a result, the two collegia musica ceased to function in the 1750s, just when the Meissen group was getting into its stride.

Both Leipzig collegia could assemble between 40 and 60 members for the twice-weekly performances and were manned by students and former students, including latterly many of Bach's own, who subsequently gained major positions in courts and churches around Germany.Footnote 8 While it can be surmised that repertoire performed by the Bachsische Collegium Musicum featured vocal and instrumental music in the weekly series of ‘ordinary’ concerts, the dispersal of scores and performing materials makes it difficult now to assess fully the repertoire that was performed. As Christoph Wolff comments: ‘It is impossible to reconstruct, even in the broadest outlines, any of the more than five hundred two-hour programmes for which Bach was responsible. Pertinent performing materials from the 1730s are extremely sparse.’Footnote 9 However, the importance of the group in stimulating the production of much of Bach's finest orchestral music, such as the solo concerti for violin and oboe, and the orchestral suites cannot be denied. It also brought Bach and his players in contact with the ‘newest kind of music’ and they frequently performed with guests, some of whom were leading musicians, including the Dresden Kapellmeister Johann Adolph Hasse.Footnote 10 It can be surmised that repertoire performed in Leipzig included concerti grossi by Handel, Locatelli and others, solo Italian cantatas by Porpora and Scarlatti, as well as German secular cantatas by Bach and others, and chamber music such as Telemann's Nouveaux Quatours (flute quartets, Paris, 1738). In these mixed programmes there would have been much chamber music by Bach, possibly including performances (presumably given by Bach himself) of solo keyboard music from the Clavier-Übung series and Das Wohltemperierte Klavier.Footnote 11 Sadly lost are a number of works performed to celebrate the ‘name days’ of the Saxon royal family, such as BWV Anh.9 and BWV 193a, or the Funeral Ode to the Queen in 1727 (BWV 198) and various congratulatory pieces for university professors (BWV 36c, 205 and 207).

The collegia musica also provided Bach with many fine instrumentalists for the performance of concerted music in services in the Nicolaikirche and the Thomaskirche on solemn feast days and during trade fairs. In Dresden there was also a connection between the collegium musicum and church music. Theodor Christlieb Reinhold(t) (1682–1755) had earlier been concerned with a collegium musicum connected with the Kreuzkirche, but following his promotion to Fourth Teacher at the Kreuzschule in 1725, he took charge of sacred music at the Frauenkirche (under construction from 1726 to 1746), and in 1741 he took over the direction of a newly founded Collegium Musicum there.

No contemporary reports, other than Klipfel's obituary, have surfaced that comment upon the activities of the Meissen Collegium Musicum, so it is uncertain how frequently or where the group met.Footnote 12 However, like the Bachsiches Collegium Musicum and the Hamburg group, regular formal concerts were mounted in Meissen and there also appears to have been involvement in concerted music in church on major feast days, and in the performance of homage cantatas to celebrate royal birthdays. Whereas the instrumental repertoire of the Leipzig groups featured in particular Italian concerti and Ouverturen (in addition to works referred to above), in Meissen the staple diet consisted of opera sinfonias, chamber symphonies and lighter concerted and chamber music (partitas, divertimenti and sonatas), as well as operatic music by Hasse. Music in the style favoured in Dresden predominated and the Meissen players were strongly interested in up-to-date repertoire, whether vocal (Hasse) or instrumental (Graun, Roellig and Wagenseil).

This first survey of the Klipfel collection aims to provide an overview of the materials, provenance and its context within Meissen. Virtually no previous scholarship has considered the Klipfel collection or its contents, or indeed, any part of the Sing-Akademie collection prior to 1940. This state of affairs was created by both a lack of access to the collection by researchers (the collection had never been curated by professional librarians or archivists), married to the general misconception in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century that the collection was largely worthless after all the original J.S. Bach manuscripts were transferred from the Sing-Akademie to the Prussian State Library in 1853. Up to World War II, Sing-Akademie items had been seen only by a handful of Bach scholars and a single Telemann scholar;Footnote 13 both Curt Sachs in his writings of 1908 and 1910 and his immediate predecessor Georg Thouret, librarian of the Königliche Bibliothek, make no mention of these materials.Footnote 14 By the time E. Eugene Helm wrote his important study, Music at the Court of Frederick the Great (1960), basing much of his observations on Sachs and Thouret, the collection had disappeared, believed to have been destroyed in 1945. While the catalogue of the entire Sing-Akademie collection has been available via RISM since 2008, interpretive research building upon this process of cataloguing so far has tended to concentrate upon the works of the major composers, such as Telemann and C.P.E. Bach, in areas of the Sing-Akademie library other than the Klipfel collection.Footnote 15 Since 1999, scholarship on the materials in the Klipfel collection has been restricted to a few mainly biographical comments made by Tobias Schwinger in the introductory section to the new Sing-Akademie catalogueFootnote 16 and some observations made by Christoph Henzel as part of a commentary on each of the collectors who contributed symphonies to the Sing-Akademie holdings. Henzel also maps out (incompletely) Klipfel's list of library numbers on the symphonies.Footnote 17 Thus, the following discussion of the structure, contents and cultural context of the repertoire, including aspects of handwriting and the dating of much of the material in the Klipfel collection, casts light on hitherto completely uncharted territory.

Part 1. Klipfel and the Meissen Porcelain Factory Collegium Musicum

Biography, personnel and activity in Meissen

Much of the following biographical information about Carl Jacob Christian Klipfel comes from the obituary published in the Berlinische Monatsschrift.Footnote 18 This biographical sketch was compiled by a writer who clearly had contact with Klipfel ante mortem and it is possible, judging by the manner and style of some of the observations, that Klipfel's memoires were incorporated into the text. The obituary gives only a partial account of Klipfel's life and career and, perhaps with the bias of an autobiography, tends to concentrate upon his relationship with Frederick the Great. Thus, some caution has to be exercised with regard to the reported exchanges between Klipfel and the king.

Carl Jacob Christian Klipfel was born in Königstein to a family of relatively modest means; his father, Wilhelm Christian Klipfel, was a garrison surgeon, who removed limbs and such like. As a five-year-old boy the young Klipfel was knocked over by a dog, which severely injured his pelvis, leaving him with a noticeable limp that required a cane for the rest of his life. School did not interest him but he was noted for his beautiful handwriting and so it was a logical step that he should become apprenticed as an artist to the Meissen Porcelain Factory at the age of 14 (in 1741). By the age of 17 he was the best of the apprentices as a painter of insects and by 1761 was considered the leading painter in the Meissen factory and was a mosaic specialist.Footnote 19 At the same time, he took some lessons on the keyboard and violin, although the obituary suggests he was largely self-taught. However, Klipfel's passion for music was aroused and, at some point c.1747–50 (the date is unknown), together with a number of friends and members of the Meissen Stadtpfeiffer, he mounted what was to be the inaugural concert of the Meissen Porcelain Factory Collegium Musicum.Footnote 20 It must be assumed that Klipfel probably did not commence copying and collecting works much before the age of 20 so the inaugural concert was probably not before 1745–6 (the earliest that a manuscript can be positively dated is c.1747).Footnote 21 The concerts caused ‘quite a stir’Footnote 22 and appear to have been frequented by the leading families of Meissen, who then opened their doors to Klipfel as the ‘founder’ of the organisation.Footnote 23 In the early stages, funding was so restricted that Klipfel became the copyist and set to work on a nightly basis to create performing materials, an activity that was to dominate his free time for the next decade or so. Principally a viola player in the group, he also sang and played timpani.Footnote 24

Apart from Klipfel, the members of the Meissen Collegium Musicum are unknown, though it appears that Johann Christian Roellig may well have performed on occasion.Footnote 25 It is very likely that some of the identified Meissen copyists – Heinrich Oehm, J.F.E. Otto and J.F Stübner – as well as the unidentified copyists – ‘Anon. Sing-Akademie 96’, ‘105’, ‘520’, ‘521’, ‘522’ and ‘599’, ‘Anon Meissen 1’ and ‘NRS Meissen 1’ – may also have been performers in the Collegium Musicum.Footnote 26 In addition to a string orchestra there were also available at various times pairs of flutes, oboes, bassoons, horns and trumpets. There can be no doubt from the evidence provided by the music performed that a violone/double bass was required.Footnote 27 If Klipfel was principally the violist in the group, the need for a keyboardist as a continuo player and the need for a choir (see comments below) indicates that one of the town cantors or organists may well have been involved. In the middle of the eighteenth century there was a cantor of St Afra Church, who doubled as Fourth Teacher at the Furstenschule St Afra; this would have been Sigismund Heinrich Kauderbach (1680–1757), or his successors Carl Christoph Bilitz (d. 1760) or Johann Liebrecht Shreger (1725–1881; in post 1758–1802).Footnote 28 The organist at St Afra, Gottlob Heinrich Günther (d.1787, in post 1748–87), was also a teacher at the school. There was also a separate Stadtcantor, Johann Christoph Möbius (d.1774; in post from 1730 to his death), who was responsible for music at both the Frauenkirche and the Dom and who was also a teacher at the Stadtschule. The Stadtorganist, who similarly covered services at both the Frauenkirche and the Dom, was Johann Gottfried Stübner (d.1770, organist 1734–70) who is likely to have been a relative of the Meissen copyist J.F. Stübner.Footnote 29 While there are single violin parts for many works, there are two copies of each violin part for many symphonies and partitas and as many as four for one partita, suggesting that a large number of string players could be assembled on occasion.Footnote 30 It would appear that the group was fairly small to start, requiring in the main single strings parts, but grew after 1754; doubling parts are present in scores created after 1755, and have frequently been added in the period after 1754 to sets of parts that predate 1754.

In time, the support of the Burghers of Meissen clearly provided financial stability for the group, enabling it to commission works from Dresden-based composers, in particular Johann Christian Roellig (b.1716). In addition to symphonies, partitas and extracts from Hasse and Graun operas that appear to have been the staple diet of programmes,Footnote 31 occasional choral works were also performed, indicating that a choir, either an ad hoc group or possibly that of the Meissen Dom, Frauenkirche or St Afra, was available to the Collegium Musicum for special events. It is more likely that these special performances took place in the Dom, since not only is the Frauenkirche very cramped for the performance of concerted works, but also the organ of the Dom had been recently repaired in 1752–3 by Johann Ernst Hähnel, a date that appears to chime with the known performance dates of the liturgical and homage cantatas, all of which can be dated between 1753 and 1759. Organ parts to the Roellig vocal works have been transposed down a tone to compensate for the high chorton pitch typically used for church organs in eighteenth-century Germany.Footnote 32

Printed wordbooks for two occasional cantatas, with texts by Gottfried Schrenkendorf, survive in Halle:Footnote 33 the birthday cantata Wie glücklich ist ein Land (SA 1177/4)Footnote 34 by J.C. Roellig, performed on 7 October 1753, in honour of Elector Friedrich August, and the J.C. Roellig cantata Tage die vor langen Jahren (SA 792/2).Footnote 35 This Singegedichte, a large-scale three-part oratorio, was performed (later in the year, possibly in November) as part of the Jubelfest observed across Northern Germany in celebration of the Treaty of Augsburg (1555) and the religious freedom it brought. The bicentenary was celebrated on the anniversary itself (Michaelis, 25 September 1755) by the performance of another cantata by Roellig, Lobe den Herrn meine seele (SA 1431).Footnote 36 Unfortunately, even though the librettist, composer and the Meissen Collegium Musicum are identified in these libretti, the location of the performance is not. The performance of two cantatas in the same programme was not unusual, for it appears that on 7 October 1753, the birthday cantata Die Lust von jenem Schreckenbilde (SA 1177(4)) was also presented. This was just one of three royal birthdays celebrated by the Collegium Musicum that summer. In July, Prince Karl [Caroli] Christian Joseph Ignaz Eugen Franz Xaver (13 July 1733–16 June 1796),Footnote 37 was honoured by the performance of the Roellig birthday cantata Die Lust von jenem Schreckenbilde (SA 1441),Footnote 38 and a month later a similar honour was bestowed on Prince Xaver when the Roellig birthday cantata Wie könnt ihr so verdrießlich sein (SA 1440)Footnote 39 was performed on 25 August 1753. Such homage cantatas were also known in Leipzig, where Bach presented a ‘loose sequence’ of special concerts dedicated almost exclusively to the electoral-royal house in Dresden, commemorating royal birthdays, name days and important political events, sometimes in the presence of royal family members.Footnote 40

It may also have been no coincidence that in 1753, in what appears not only to have been the busiest season for the Meissen Porcelain Factory Collegium Musicum, but one in which it repeatedly expressed its loyalty to the Saxon royal family, the factory (which was owned by the Elector) produced its famed ‘monkey orchestra’ (Figure 1).Footnote 41 Perhaps not totally with the Meissen group in mind, the musical figurines were designed by Johann Joachim Kaendler, based on the satirical illustrations of the French artist Christophe Huet, working in the ‘singerie’ style of elegant monkeys that was hugely popular with the French aristocracy during the eighteenth century. The set consists of 22 figures including a conductor, a music stand and 20 other figurines that fall into three categories: firstly, performers associated with a collegium musicum or court orchestra (a violinist, gamba player, flautist, oboe [or chalumueau] player, bassoonist, clavier player, French horn player, trumpeter, timpani player, two female singers and a boy treble); secondly, instruments of the home (guitarist and harpist); and thirdly, instruments associated more with peasant and ‘pastoral’ music making (fife and drum player, bagpiper, hurdy-gurdy [Leier] player and triangle player). The pastoral style was prized by courts such as Würtenburg and Dresden at the time, hence such pseudo-peasant figurines would have appealed to the Elector of Saxony.Footnote 42 About the same time (c.1753–4), Meyer and Kaendler worked on the ‘Galante Kapelle’, a fictional orchestra of 16 members with a similar set of characters to the Monkey Orchestra including a conductor, flautist, oboist, bassoonist, two violinists, cellist, trumpeter and lutenist (all male); a female hurdy-gurdy (Leier) player and harpist; plus four female and one male singer.Footnote 43 The figures represent ‘courtiers’, again in less formal ‘pastoral’ dress, rather than depicting professional musicians in livery.

Figure 1. Meissen monkey orchestra figures.

Even though it exists in score format only and no performance date is known, the dramatis personae: ‘Meissen’, ‘Music’, ‘Neid’ and ‘Glück’ of the J.C. Roellig cantata Nachhall schall auf unsre Lieder (SA 1177/3)Footnote 44 indicate that this work was very likely another performed by the Meissen Collegium Musicum. This is one of a series of secular cantatas by Roellig, with allegorical characters, often not requiring a chorus. Others include Wie glücklich is ein edles Herz (SA 797/1); Herr Schulze hört nur einmal an (SA797/3); Die Bauer und der Weinschenke (SA 7967/4); Wilkommen vom Himmel erbetene Stunden (SA797/5) and Der durch Musik überwundene Neid (SA1177/1).

Two wedding cantatas by Roellig can be found in the Klipfel collection: Ihr Himmel jauchzet Gott entgegen (SA 1426), dated 1754, and Herr hebe an zu segnen (SA 444) (c. 1758–9).Footnote 45 It is tempting to believe that the latter might have been the music that celebrated Klipfel's own wedding to Christiane Catharine, the daughter of co-worker Christian Gottlieb Liebscher, which took place in the Frauenkirche in Meissen on 22 May 1759.Footnote 46 The union was to produce a daughter, ‘Eleanora Sophia Catherina’ (b. 20 September 1761–1836)Footnote 47 and a son, Carl Wilhelm Klipfel (16 February 1764–13 September 1827), who was also a good amateur musician, a member of the Sing-Akademie from 1810, and a modest composer in his own right.Footnote 48

In addition to homage works, cantatas for the principal feasts of the liturgical year were also performed by the Meissen Collegium Musicum, suggesting that it provided the musicians, in the tradition of Adjuvantenmusikanten (lay or amateur supporting instrumentalists), for feast-tide services in the Dom. Klipfel's close association with Roellig is once again highlighted by the repertoire; 39 of the 42 choral works in the Klipfel collection are by J.C. Roellig (Table I). Over two thirds of these are autograph scores while there are sets of parts for half of the cantatas. In all cases, the parts (where they exist) have been copied by Klipfel and in three cases, both the score and parts are by Klipfel. There are works for Christmas, Easter and various Sundays in Trinity.

Table I. Sacred cantatas by J.C. Roellig, arranged in order of the liturgical year

| Title of cantata | Sing-Akademie shelf no. | Liturgical association | Format and copyists (K= Klipfel, R= Roellig) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bringt, ihr bewegten Engels Zungen | SA 441 | Christmas | Score(K) & parts(K) |

| Uns ist ein Kind gebohren (1755) | SA 1435Footnote 1 | Christmas | Score(R) & parts(K) |

| Wilkommen ihr fröhlichen Zeiten (1756) | SA 1434 | Christmas | Score(K) & parts(K) |

| Der Siegesfürst kommet | SA 795 | Easter | Score(R) |

| Jauchzet ihr Himmel freue dich Erde | SA 1425 | Easter | Score 1(R) Score 2(K) & parts(K) |

| Man singet mit freuden vom siege (Geistliche Posien, Rambach) | SA 1427 SA 1428 | Easter | Score(R) Score(K) |

| Der Siegesfürst kommet (different work) (Geistliche Posien, Rambach) | SA 1437 | Easter | Score(K) |

| Kommt gläubige Sellen betrachtet des Leiden | SA 1430 | Easter | Score(K) |

| Der Herr hat gesagt | SA 796 | Johannistag | Score(K) & parts(K) |

| Leben und Wohltat hast du an mir geben | SA 445 | Johannistag | Score(R) & parts(K) |

| Welt dein purpur stinkt mich | SA 1424 | Trinity 1 | Score(R) |

| Was ist doch das vor eine Gnadenkrone | SA 442Footnote 2 | Trinity 8 | Score(K) & parts(K) |

| Der Herr hat gesagt (different work) | SA 1436 | Trinity 15 | Score(R) |

| Ihr werdet nur vergebens | SA 1438 | Trinity 20 | Score 1(R) Score 2(K) & parts(K) |

| Jesu Blut komm über mich | SA 1429 | Communion | Score(R) & parts(K&R) |

| Ach wo kommt doch das böse Ding her | SA 443 | unknown | Score(R) & parts(K) |

| Willkommen ihr flammenden Triebe (1757) | SA 1423 | unknown | Score(R) |

| Singt Singens ungewohnte Zungen | SA 1432 | unknown | Score(K&R) |

| Wer Ohren hat der höre | SA 1433 | unknown | Score(R) & parts(K) |

1 Published by Ortus Verlag.

2 An autograph score can also be found in the main collection of the Berlin State Library D-B Mus.ms.18636/8

Two choral works are by composers from further afield: an Easter cantata Seele geh in tiefstem Leide (SA178/3) by Johann Gotthardt Abt (1700–99)Footnote 49 and the cantata Herr Gott dich loben wir by C.H. Graun. There is also the birthday cantata Spielet und lachet ihr munteren Saiten (SA 1422) for solo soprano, oboe, violin and cembalo by another local Dresden-based composer, ‘Hof organist Richter’, presumably Johann Christoph Richter (15 July 1700–19 February 1785).Footnote 50 The remaining items are secular cantatas for soprano and bass voices and strings by another composer local to the Meissen-Dresden area, Christoph Ludwig Fehre (1718–72),Footnote 51 or works for solo voice and keyboard (by Hiller and C. W. Klipfel), the copies of which are both post-1763.

Accompanist of Frederick the Great: 1760–1

Towards the end of 1760, in the period from around 8 November to 8 December,Footnote 52 Frederick the GreatFootnote 53 quartered in the palace of Meissen, with his troops nearby.Footnote 54 Without his Kapelle, which remained in Berlin, Frederick sought local musicians to enable him to continue his daily musical soirées, and in particular he sought someone to accompany his flute playing on the clavier.Footnote 55 Klipfel was recommended and was immediately found to be an extremely proficient harpsichordist who (according to the obituary) soon earned cheers of encouragement from the king.Footnote 56 The experience of playing to such a refined and able player encouraged Klipfel to a much higher level of attainment in his own performance, though he must have had mixed feelings about meeting the man who had caused such destruction during the bombardment of Dresden only five months earlier and the destruction of the bridge over the Elbe at Meissen in 1759. Despite the differences in their social standing, and the fact that Klipfel appears to have received informal monetary payments for his services,Footnote 57 Klipfel and the king were musical equals, gifted amateurs brought together by their mutual love for music, a common interest that was to colour their subsequent interaction (and one that undoubtedly would not have occurred between the king and his professional accompanists, C.P.E Bach and Carl Friedrich Christian Fasch). Lengthy conversations were also part of the proceedings and while music, particularly the music of Graun and Hasse, remained central to these exchanges, the king also enquired after more local topics and was particularly interested in the workings of the Meissen Porcelain Factory. According to the obituary, Klipfel gained the king's trust by his ‘humble openness from which his character shone forth’Footnote 58 and for his ‘frank responses’.Footnote 59 While such language suggests a rather idealised picture of the relationship, most probably as it was remembered by Klipfel towards the end of his life, there is evidence to indicate that a friendship grew between the two men that was to last until Frederick's death.

Frederick moved to Leipzig on 8 December 1760, where he stayed at the Apel House until 17 March 1761.Footnote 60 Here he continued his daily evening concerts, along with Quantz, Benda (senior), and the singers Porporino, Paulino and Tossoni. He also sent for his second harpsichordist, C.F.C. Fasch, from Berlin to be present.Footnote 61 However, Frederick himself may no longer have been a participant; Carlyle reports that ‘from himself [the king] there is no fluting’.Footnote 62 Frederick left Leipzig on 17 March 1761 to return to Meissen, where he remained until 3 May 1761. Notified of the concerts by his generals and aides, the king honoured the Meissen Collegium Musicum by attending several performances.Footnote 63 Once, Frederick expressed a wish to hear the programme again, so Klipfel devised a special surprise for the king. In ‘early spring’ (March–April 1761), with the help of court officials, Klipfel set up the orchestra in the garden under the window to the king's rooms and commenced the concert with a symphony by Graun. The surprise complete, the king came to the window and remained there to listen for the entire duration of the 90-minute performance in which Klipfel sang an aria, and he was most gracious in his applause, requiring a Chamber-hussar to express his pleasure and thanks.Footnote 64 MacDonogh confirms that the ‘Meissen manufacturers went so far as to serenade the king’ who himself reported that ‘they have a band which plays prettily.’ Footnote 65

Klipfel in Berlin: 1763–1804

In his questioning of Klipfel about porcelain manufacture, Frederick II clearly had an ulterior motive. The Prussian monarch had taken control of the Meissen factory in 1756. Not only did he commandeer existing stocks of porcelain (described as ‘white gold’) to sell in order to raise badly needed funds for the war effort,Footnote 66 but he was also in the process of commissioning a great amount of material to be taken back to Berlin, including the celebrated ‘Mollendorf’ service, the design of which Frederick collaborated on with Klipfel. This activity is illuminated by a letter he wrote in March 1761:

TO MADAM CAMAS (at Magdeburg, with the Queen).

MEISSEN, 20th March, 1761.

I send you, my dear Mamma, a little trifle, by way of keepsake and memento [snuffbox of Meissen Porcelain, with the figure of a dog on the lid]. You may use the box for your rouge, for your patches, or you may put snuff in it, or BONBONS or pills: but whatever use you turn it to, think always, when you see this dog, the symbol of fidelity, that he who sends it outstrips, in respect of fidelity and attachment to MAMAN, all the dogs in the world; and that his devotion to you has nothing whatever in common with the fragility of the material which is manufactured hereabouts.

I have ordered Porcelain here for all the world, for Schönhausen [for your Mistress, my poor uncomplaining Wife], for my Sisters-in-law; in fact, I am rich in this brittle material only. And I hope the receivers will accept it as current money: for, the truth is, we are poor as can be, good Mamma; I have nothing left but honour, my coat, my sword, and porcelain … Footnote 67

At the same time Frederick II was also attempting to resurrect the Berlin Porcelain Factory, which had been founded with his financial support in 1751, but had since foundered under Wilhelm Caspar Wegele's control and finally closed in 1757, mainly due to the poor quality of the product. The result of Frederick II's stay in Meissen was to engage Klipfel to travel to Berlin in early 1761 (escorted by armed hussars riding fore and aft to ensure Klipfel's safety) where he remained for eight days to inspect the factory before travelling on to Leipzig to report to the king. At the same time Frederick negotiated with his protégé, the leading Berlin financier Johann Ernst Gotzkowsky (1710–75), to invest funds in the factory, which he did. The factory was re-commissioned on 11 January 1761, with 146 workers under the management of Johann Georg Grieninger (1716–98) who was a professional administrator.

The obituary is vague about the chronology. There is the implication, following his report to the king in Leipzig in 1761, in which Klipfel suggested that it would be possible to make a going concern of the Berlin factory if certain recommended courses of action were followed, that it was at this point that Klipfel was offered the post of Royal Inspector of [Porcelain] Manufacture. However, it appears that it was only following the signing of the Treaty of Hubertusburg (15 February 1763) that concluded the Seven Years War that the king offered Klipfel the post of second in seniority in the department of painting in Berlin, with a salary of 1,100 Thalers, making him the fifth most highly paid employee at the factory.Footnote 68 This was an offer not to be refused since, from 1757, the Meissen workers had had to endure the lowering of their wages by a third in order to keep the porcelain factory operational during the war period.Footnote 69 It was from March 1763 that the factory first produced mosaic-decorated ware, indicating Klipfel had only shortly arrived at the factory, the last artist to transfer from Meissen to Berlin.Footnote 70 (Frederick was particularly fond of a particular type of decoration around the edge of the tableware in which Klipfel excelled.)Footnote 71 He joined another Meissen modeller, Friedrich Elias Meyer,Footnote 72 and the painters Karl Wilhelm Böhme and Johann Balthasar Borrmann, who had previously moved to Berlin in 1761. Copies of works by Hiller in the Klipfel collection dated 1762 on paper with Saxon watermarks, confirm this later date to be correct.Footnote 73 What is clear is that the performing materials that Klipfel had so painstakingly assembled were transported with him to Berlin, with the implication that the Collegium Musicum in Meissen was dissolved. In the same year (1763) Roellig relocated to Hamburg. ‘As was common with provincial collegia musica, the private character of such societies is evident from the fact they depend upon the initiative of individuals and cease their activities when these individuals move elsewhere or die.’Footnote 74

1n 1763 Gotzkowsky went bankrupt and Frederick stepped in and bought out the Porcelain Factory himself on 19 September (for 225,000 Thaler), renaming it the Königliche Porzellan–Manufaktur Berlin (KPM). Klipfel very soon found himself in charge of administrative aspects of the running of the factory as a result of his deep understanding and knowledge of the financial aspects of porcelain manufacture.Footnote 75 From 1763–86 he held the post of Debitsbeamte, and from 1783 to 1786 he was also Malereibuchhalter, in charge of production and pricing. By 1770 Klipfel is mentioned as ‘Inspektor der Berliner Manufaktur’.Footnote 76 Frederick, who involved himself in the decision-making process, received monthly reports on production, sales and artistic designs from Klipfel in person.Footnote 77 Klipfel reports how, on ‘repeated trips to Sansouci on affairs of work’, he was ‘delivered in a carriage of the Royal Marshal pulled by six horses’.Footnote 78 In 1770 it was Klipfel, rather than Grieninger, that the king approached to discuss design and production of a dessert service to be sent to Catherine II, Empress of Russia.Footnote 79 To Frederick's great pleasure, the factory thrived, even if in the early days the principal customer was the king himself!

According to Grieninger, Klipfel remained a favourite of the king and continued to have access to the royal music making at court; Frederick ‘granted him admittance to his concerts in perpetuity at which he himself played the flute’ and, according to the rather idealised account in the obituary, he was allowed the unprecedented privilege, normally only accorded to Quantz, of standing next to the royal performer, praising him on his performance.Footnote 80 Frederick also continued to seek Klipfel out in order to discuss visiting virtuosi and performance at the Berlin opera. Klipfel was honoured for his distinguished service by the appointments as Hofkammerat (1782) and Geheimer Hofkammerat (privy councillor) in 1786. Six weeks before the king's death in 1786, Klipfel was summoned to Potsdam for a final audience with the ailing monarch. After some preliminary discussion of matters about the factory, the king then expressed his desire to have seen Klipfel one last time in order to wish his friend goodbye.Footnote 81 Klipfel was to live another 20 years. In September 1786, Frederick the Great's successor, Friedrich Wilhelm II, appointed Klipfel co-director of KPM alongside Johann George Grieninger, a post that provided privileges such as a fine carriage. A year later the factory was placed under the control of Friedrich Anton von Heinitz, State Minister of Mining at the Department of Mining and Metallurgy in the Commission Directorate (MK) who also oversaw brass and steel manufacture and coinage. As a result, the directors of KPM lost direct access to the king.Footnote 82 In 1787, the now aged Grieninger and Klipfel appointed their sons as Directinassisten, with the title Hofrath, to assist and eventually succeed their respective parent. ‘Grieninger II’ (also named Johann George Grieninger, 1757/8–1826) served to 1814, at which time he retired. Between 1804 and 1807, ‘Klipfel II’ (Carl Wilhelm Klipfel) was ‘Hofrath und mitgleid der Commission Königliche Porzellan Manufactur’ and served to 1827.Footnote 83 In 1797, on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, Klipfel senior was honoured by the production of a special plaque (Portätplakette) in the form of a medallion created by the factory which features a profile of his bust and bears the inscription: ‘C.J.C. KLIPFEL KOEN. PREUS. GEH. CAMMERRATH AND PORC. MANUF. DIRECT.’ A year later, Grieninger was commemorated by the production of a similar Porcellanmedaillon. Footnote 84

The demands of the factory meant that Klipfel had less time to devote to his music than he had done in Meissen, but he did manage to involve himself as a viola player with musicians who would ultimately be connected to the founding of the Sing-Akademie Berlin in 1799. He also played the piano (clavier) privately at home. To what extent Klipfel organised performances in Berlin is unclear, though some works collected prior to 1763 received performances in Berlin, possibly in a sacred context, as exemplified by the libretti printed in Berlin of two Roellig cantatas SA 445, Leben und Wohltat hast du an mir geben, and SA 1436, Der Herr hat gesagt. Footnote 85 Indeed, the material that Klipfel brought to Berlin would have been attractive in a city where, ‘from the postwar era until Frederick's death in 1786, the official musical repertory was almost exclusively made up of music composed before the mid-century (1756) that got repeated, both in the opera house and in the king's private chamber music.’Footnote 86 It was via Klipfel's son, who was a member of the Sing-Akademie from 1810, that this large collection was acquired by the library. The material, donated c.1810, would have particularly attracted the music director, Carl Friedrich Zelter (1758–1832), who stated: ‘I have been to the Konigliche Bibliothek three times. It is very strong and contains rare musical codices and manuscripts from the sixteenth century that are magnificently endowed and well preserved. I myself am interested in the things from the second half of the eighteenth century, for the further enrichment of my Sing-Akademie.’Footnote 87

Part 2. The repertory and structure of the Klipfel collection

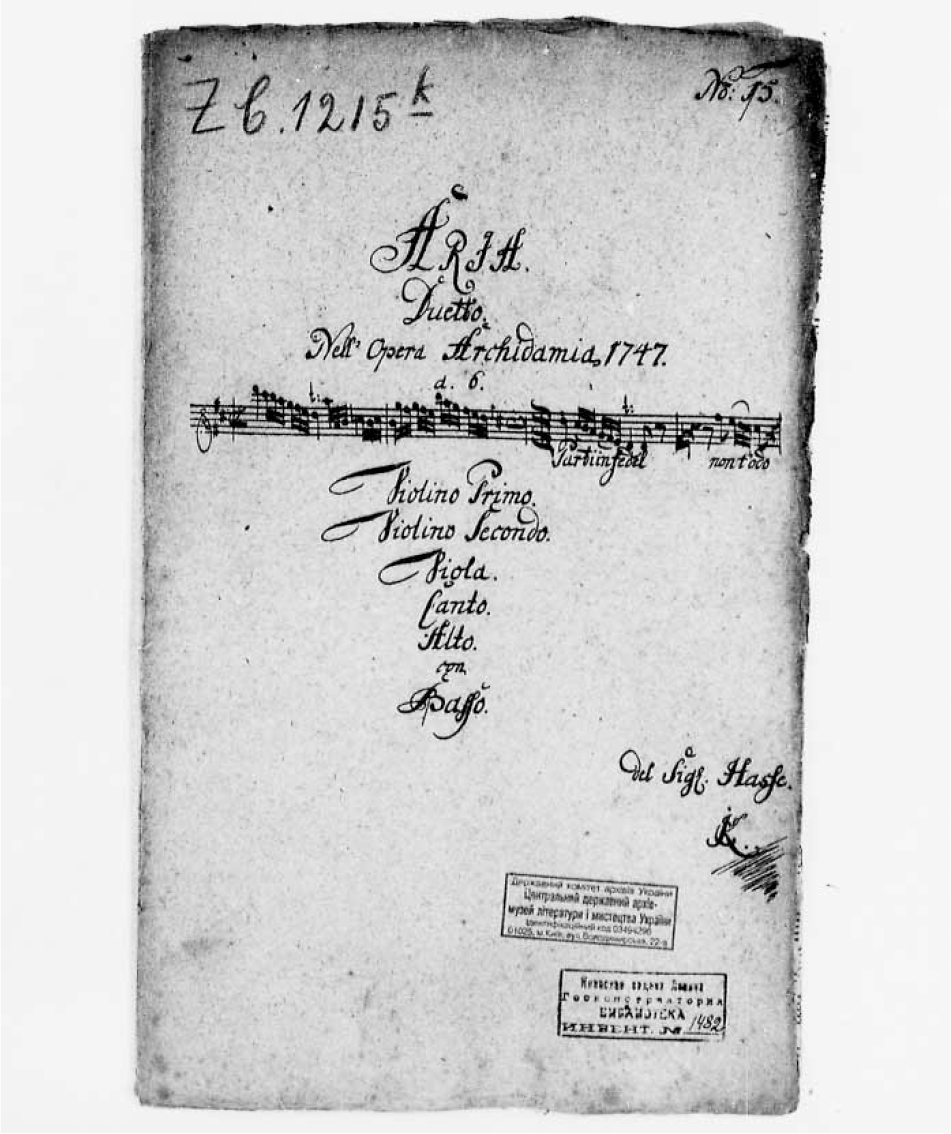

Most of the material in the collection was copied out by Klipfel himself and is identifiable by his own very distinct and extremely neat hand on the scores and parts, or by the library covers he created for the sets of parts on which he generally added his monogram in the bottom right-hand corner (Figure 2). These covers make it possible to identify works that he acquired which had been copied by other hands. However, the full extent of Klipfel's collection may never be known since there has been some dispersal of material (see discussion below about Klipfel's catalogue numbers); sets of performing parts to works known to have been performed in Meissen are missing,Footnote 88 and some sets of parts are incomplete. In addition, there are some works in the Sing-Akademie holdings that are now not directly associated with Klipfel (since his hand is not in the music, nor is there an identifying library cover which may have been lost/separated from the source) but which were undoubtedly originally part of the collection. Examples of such works would be the Roellig autograph scores and parts, which clearly found their way into the Sing-Akademie Library via Klipfel, rather than by another other route.Footnote 89 In total, there would appear to be in excess of 520 manuscripts in the collection.

Figure 2. Cover sheet for the parts to Hasse's aria from to Archidamia, 1747.

While most composers are represented by between one and six manuscripts, only five composers are represented by more than ten, they are: C.F. Abel (20), Wagenseil (31), ‘Graun’ (composer unspecified, 56), Hasse (60) and J.C. Roellig (180+). The greater part of the collection was amassed in Meissen, but copyists and paper types confirm that there were some additions after 1763. As might be expected, the Klipfel collection features composers who worked and lived in the Dresden area, with operatic music of Hasse and the instrumental and choral music of Roellig being of particular interest. Very few Italian composers are represented and, significantly, this music was collected prior to 1763. While the Italian style was extremely popular in the court of Dresden (the court provided one of the principal conduits by which the music of Vivaldi came to be known and accepted by German musicians and composers),Footnote 90 it was either not one that was performed extensively in post-1763 Berlin, or it was not of great interest to Klipfel. The works of the Graun brothers were also readily available to Klipfel prior to 1763 and, as indicated by the discussion above, greatly interested him.

The move to Berlin brought Klipfel in touch with new repertoire and he continued to expand his collection after 1763. Indicating that this was more a process of getting to know new music than preparing for planned performances, nearly all of the acquisitions in Klipfel's hand were scores rather than set of parts. As might be expected, some is repertoire by composers based in Berlin, Schwerin and Mannheim, which was new to Klipfel. These included five symphonies and two piano concertos by C.P.E. Bach;Footnote 91 a symphony each by J.W. Hertel (SA 2290) and J.P. Kirnberger (SA 2299); three symphonies by F.X. Richter,Footnote 92 six by J. Stamitz (SA 2374), a symphony (SA 2294) and two trio sonatas (SA 2373) by Leopold Hoffman; a partita by Wiedner (SA 3189) and the sinfonia to La Didone abbandonata by J.G. Schwanenburg (SA 2283). Perhaps based on these few scores, Christoph Henzel talks of a ‘realignment’ in the collection,Footnote 93 but the evidence provided by the majority of scores acquired after 1763 suggest that Klipfel continued to favour the styles with which he was familiar; the greater number of works added to the collection after 1763 were additions to the holdings of music by composers which he had previously collected and performed in Meissen. Significantly, the music of composers who arrived in Dresden after 1763 appear in the collection, such as Johann Gottlieb Naumann, who only returned to Dresden in 1764 as Court Kirchenkomponist after travel in Italy. Clearly, Klipfel was attempting to keep abreast of the most recent developments in the Dresden area (Table II).

In the list below, composers represented in the collection are grouped geographically by their area of activity. The number in brackets indicates the quantity of manuscripts in the collection while the suffix indicates whether the works of that composer were collected entirely before 1763(D), entirely after 1763(B) or whether Klipfel continued to acquire music of this composer both in Dresden and Berlin(*):

(1) Composers working in the sphere of Dresden / Meissen: Abel, Carl Friedrich (20*); Adam, Johann (5D); Binder, Christlieb Siegmund (2B); Drobisch, Johann Friedrich (2D); Fehre, Christoph Ludwig (2D); Förster, Christoph (1D); Gebel, Georg (2D); Götzel, Franz Joseph (1D); Harrer, Johan. Gottlieb (7*); Hiller, Johan Adam (31*); Hasse, (60*); Horn, [Christian Friedrich] (1D); Naumann, Joh, Gottlieb (2B); Neruda, Johann Baptist Georg (5D); Quantz, Johann Joachim (1D); Richter, [Johann Christoph] (1D); Roellig, Johann Christian (180+*); Schaffrath, Christoph (2D); Schürer, Johann Georg (6D); Steinmetz, Johann Erhard (5D)

(2) Other Saxon composers:Footnote 94 Abt, Johann Gotthardt (3D); Hartwig, Carl (2D); Schwägrichen, Gottfried Siegmund (7D); Schwanenberg, Johann Gottfried (1B); Wiedner, Johann Gottlieb (1B)

(3) Composers associated with Berlin and other northern German centres: Agricola, Johann Friedrich (1D); Bach, C.P.E. (9B); Benda, Franz (8D); Benda, Georg (2D); Graun [?] (10*); Graun, Carl Heinrich (46*); Hertel, J.Wn. (1B); Kirnberger, Johann Philip (1B); Klipfel, Carl Wilhelm (1B); Krause, Christian Gottfried (6D)

(4) Composers from the German centres of Stuttgart, Mannheim and Munich: Camerloher, Placidus von (2*); Holzbauer, Ignaz Jacob (4D); Kleinknecht, Johann Friedrich (5*); Richter Franz Xaver (2B); Stamitz, Johann (6B)

(5) Vienna- and Prague-based composers: Hofmann, Leopold (4*); Ordonez, Carlos D (1D); Orschler, Johann Georg (2D); Wagenseil, Georg Christoph (31*)

(6) Italian composers: Pergolesi, Govanni Battista (2D); Platti, Giovanni Benedetto (1D); Reluzzi, Giovanni Ambrogio (2D); G.B. Sammartini (4D)

Table II. Works added to the collection by composers who had already been collected prior to 1763: a comparison of formats between pre- and post-1763 copies

| Composer | Genre | Works on Saxon paper | Works on Berlin paper | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | Parts | Score | Parts | ||

| Abel | Symphonies | 0 | y | y | 0 |

| Camerloher | 0 | y | y | 0 | |

| Graun | y | y | y | y (two in both score and parts) | |

| Wagenseil | y | y | y | y | |

| Graun | Opera sinfonias | y | y | y | y |

| Hasee | y | y | y | 0 | |

| Hiller | 0 | 0 | 0 | y | |

| Abel | Concertos | y | 0 | y | 0 |

| Graun | y | y | y | 0 | |

| Roellig | Partitas/divertimenti | y | y | y | 0 |

| Harrer | y | y | y | 0 | |

| Hiller | y | y | y | 0 | |

| Kleinknecht | y | y | y | 0 | |

| Steinmetz | y | y | y | 0 | |

| Wagenseil | y | y | y | 0 | |

The collection divides into four broad areas:Footnote 95

(1) Concerted works: symphonies, ‘ouvertures’, partitas and suites, extracts from operas, sacred and occasional choral works

(2) Works for a small chamber groups: works for two, three, four, and five or more players such as quadro and trio sonatas, divertimenti and partitas

(3) Works for solo keyboard presumably for Klipfel's own use

(4) Songs and other works for solo voice and instruments/keyboard

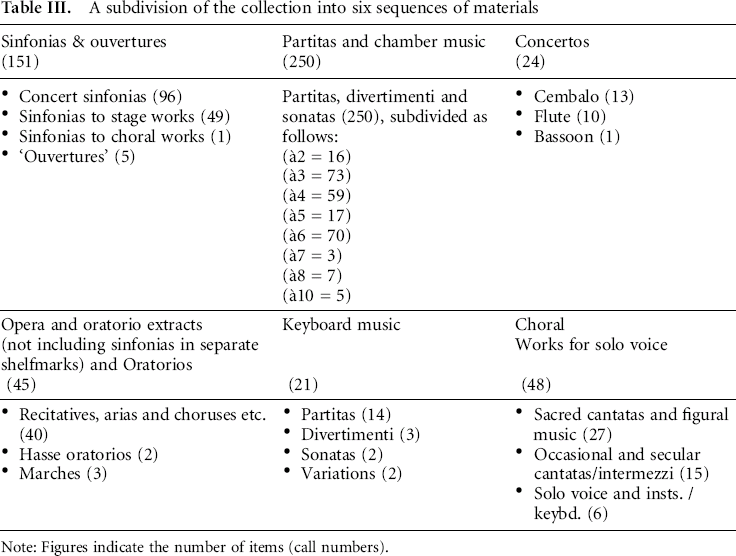

The collection can be further divided into six sequences of materials. The number of items within each group in Table III provides an indicator to the scale of the collection. The table illuminates the large number of partitas and symphonies and sinfonias, compared to the very few concertos.

From the earliest acquisitions Klipfel added library covers to many of the sets of performing parts. Many, though not all, of these are numbered. (For an example see the top right-hand corner of the cover sheet in Figure 2.) There appear to be three independent sequences of numbering of the sets of performing parts in the collection:

(1) Concert symphonies and sinfonias/overtures to stage works: listed in Appendix, Catalogue Sequence 1

(2) Partitas and divertimenti: listed in Appendix, Catalogue Sequence 2

(3) Excerpts from stage works: listed in Appendix, Catalogue Sequence 3

It is clear that while many covers were created contemporaneously with the set of parts, some post-date the parts to which they belong by a number of years. It would be extremely convenient to find that the numbering system indicates a chronology, but the sets of the parts in the library sequence are not in date order; some of the covers date from as early as 1747, but it appears the library numbers were added after 1755, and possibly as late as 1758–60. This implies that the creation of a catalogue of the contents of the collection was intended, if not completed at this time.Footnote 96 The ordering of the library sequences appears to be haphazard, though in the sequence of partitas, suites and divertimenti, one finds that the majority of the works by Roellig are in batches of three or six items, reflecting the eighteenth-century practice of publishing works in groups of six. Thus, it is possible to infer that some of the missing items (nos 31, 41–2 and 76–8) are by Roellig, and are possibly some of the many works in the Klipfel collection now lacking a library cover.Footnote 97 Appendix 2 also highlights how the items that constitute Raccolta V (Breitkopf, 1761) appear as six consecutive numbers, whilst items that belong to other collections listed in Breitkopf catalogues are all separated in the Klipfel collection.

What is perhaps surprising is the high proportion of scores in the collection, which are not included in the library numbering. Klipfel indicated in the biography that when he acquired new music, he would first write out the music in score format,Footnote 98 a way of working that enabled Klipfel to increase his understanding of the theoretical aspects of music.Footnote 99 While this assertion holds true for works acquired after 1763, and for some works collected before 1763 where scores and parts in Klipfel's hand are clearly contemporaneous (as in Roellig's Partita in A),Footnote 100 paradoxically, in the majority of cases the score post-dates the parts by several years.Footnote 101

This raises several questions: what were Klipfel's sources? Were they scores or parts? From the thematic catalogues published from 1761, it can be determined that much of the instrumental music in his collection was available via Breitkopf. Was the ultimate source therefore Breitkopf (which sold music as manuscripts in both score format and in parts)? Did Klipfel have an arrangement to copy scores from musicians who had purchased copies directly from Breitkopf, possibly paying a partial fee to help defray the capital cost of the original purchaser? Barbara Wiermann also suggests another model, whereby works could be hired for short periods from commercial lending organisations.Footnote 102 Though no evidence of such an activity has yet been recognised in Dresden in the 1750s, this appears to have been the means by which Klipfel acquired much of the instrumental material directly from Roellig. It cannot be ruled out that Klipfel was a source of materials acquired by Breitkopf.

Orchestral music

In the largest identifiable sequence of catalogue numbers, numbering some 111 sets of parts (see Appendix 1 for full list), Klipfel included concert symphonies and sinfonias to stage works, the latter played as independent works by the Meissen Collegium Musicum. About half of the items in the sequence are unaccounted for, but some of these ‘missing’ works may be the eight items listed at the foot of Appendix 1 that have a number missing, or are awaiting an allocation; upon these Klipfel wrote ‘No…’ on the cover and then did not add a figure. There are some apparent repetitions of library number. In the case of the Abel symphony numbered No. 1 in Klipfel's library sequence, Klipfel possessed in score all six symphonies of Abel's Op. 4., two of which (Op. 4 No. 1 and Op. 4 No. 2) also appear in the collection in sets of parts corresponding to Nos 1 and 2 in Klipfel's catalogue sequence. This suggests that the Klipfel ‘library’ number here appears to relate to the subdivision of the opus rather than to his collection. There are three other repetitions (No. 5, No. 11 and No. 64). In two cases, it is between a symphony and a sinfonia to a stage work.

With the caveat that the Klipfel catalogue numbers indicate that material is missing, the balance between scores and sets of parts in the collection does provide a strong indication of the repertoire performed by the Meissen Collegium Musicum; opera sinfonias were favoured over concert symphonies; there is an almost total absence of music by Italian composers, and there are few French ‘ouvertures’ (only two of the five works exist in parts). Unlike in Leipzig, where solo concertos were a feature of the programmes, few solo concertos appear to have been performed in Meissen; there are only sets of parts for five of the 24 concertos in the Klipfel collection (two each for cembalo and flute, and the only bassoon concerto). This is probably because the Leipzig collegia musica could draw on more virtuosic players, including Bach himself. It is tempting to suggest that the parts to the Quantz Flute Concerto in C (SA 2937–QV5.5)Footnote 103 might have been prepared in order that Frederick II might have the opportunity to play some concerted music during his sojourn in Meissen.

While Klipfel collected a large number of symphonies, fewer than half of the surviving works appear to have been performed; of the free-standing concert symphonies, there are more works in score format (63) than in sets of parts (41).Footnote 104 Of these sources, only 12 works exist in both formats and, highlighting the way Zelter dispersed sources within the collection at the beginning of the nineteenth century, there are only two instrumental works where the score and parts share the same shelf number. Symphonies by C.P.E. Bach, Fehre, Hertel, Hoffman, Kirnberger, Ordonez, Richter and Stamitz exist as scores only. The performed repertoire included: one each by F. Benda, P. Camerloher, Hiller, Holzbauer, Neruda and Schürer; two each by Abel and Adam; three by Wagenseil; and five by Graun. It might appear that, with 19 sets of parts, Roellig was the most often performed symphonist by the Meissen musicians. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that the longest intact sequence of items in the Klipfel catalogue (items 67–74), consists mainly of Roellig symphonies. Indicating the popularity of opera sinfonias, a greater proportion of these works (39 of the 49 shelfmarks) survive as sets of parts, with works by Graun (12) and Hasse (23) dominating the repertoire. Only one work by an Italian can be found in the collection of orchestral works, the Sinfonia to L'Olimpiade by Pergolesi (SA 2468).

Music for ensemble: partitas, suites, divertimenti and sonatas

The largest segment of the collection consists of the partitas, divertimenti and sonatas for varying combinations of instruments. Divertimenti were multi-movement works for a small chamber ensemble, generally in three movements, fast-slow-fast. The partita (in the main multi-movement works for three or more instruments), was particularly popular in the Dresden area in the mid-eighteenth century and by far the most popular genre in the collection. Partitas consisted of four or five movements but, reflecting the links with the Polish court, the majority in the collection belong to the distinct subgenre that has been identified as the ‘Dresden Partita’, where the last two movements are almost invariably a minuet (and trio) followed by a polonaise or, occasionally, a polacca, with the trio section occasionally cast as a ‘massur’ (mazurka).Footnote 105 Partitas in the Klipfel collection were composed principally by musicians with a link to Dresden or further afield in Saxony: Johann Adam (2); Johann Friedrich Drobisch (2); Georg Gebel (2); Johann Gottlieb Harrer (6); Johann Adam Hiller (12); Johann Ludwig Horn (1); Johann Georg Schürer (2); Johan Erhard Steinmetz (4) from Dresden and Schwägrichen (7); and Wiedner (1) from greater Saxony. Dresden-style works by Christian Gottfried Krause (4), a Berlin composer, were available to Klipfel prior to 1763. Those by Wagenseil (2), which originate from furthest afield, are in a three-movement fast-slow-fast format associated with the Viennese version of the partita and emergent divertimento. However, again, Johann Christian Roellig dominates the collection of partitas with over 90 items, several in one or more arrangements for differing instrumental combinations.

The instrumentation of the Dresden partita was particularly variable; the most numerous in the collection being ‘à3’ (of which there were 53 for the trio sonatas combination of two violins and bass and seven for two flutes and bass), ‘à4’ (40 are for a string quartet combination, one for three violins and bass, seven for flute, two violins and bass) and ‘à6’ (of which the majority are for two flutes and strings (27), or two oboes and strings (16), or two horns and strings (16), and two trumpets and strings (5)). While the divertimenti and sonatas can be viewed exclusively as chamber works, requiring just one player per part, the performing group for the partita as a genre was much more flexible. Again, it is tempting to suggest that the eight works for solo flute and cembalo (all by Roellig)Footnote 106 was repertoire that Klipfel provided for the king to play, perhaps quickly commissioned from Roellig, particularly since two divertimenti are arrangements of works which elsewhere in the collection are for four-part strings.Footnote 107 In contrast, others are designed to be performed in a larger space or even out of doors, such as Partitas 1, 2 and 3 of the set of six by Roellig that comprise SA 2415; these are written ‘à10’ for pairs of trumpets, oboes, bassoons and strings, while two partitas in Eb (SA 2415/5 and SA 2415/6) are scored ‘à7’ for pairs of horns, oboes, bassoons and bass (with no upper strings). In addition, whole sets of six partitas might be arranged for a completely different performing group. For example, the second suite from Roellig's Raccolta V,Footnote 108 which is scored ‘à7’ for a pair of trumpets, oboes, bassoon and four-part strings, also exists in two other arrangements: ‘à6’ for two trumpets, and strings,Footnote 109 and ‘à2’ for violin and cembalo.Footnote 110 It also comes as no surprise to find that many partitas were performed orchestrally, particularly those with obligato wind instruments. About half of the set of parts have two sets of violin and bass parts, some have three copies of each violin and bass part,Footnote 111 and one, a partita in D scored for two trumpets and strings (SA 2334) has four of each violin part and three bass parts, nearly all in the hand of Klipfel (‘Sing-Akademie 522’ copied only three folios, all the parts were otherwise copied by Klipfel), perhaps suggesting an outdoor performance was envisaged, such as the one mentioned above, organised for Frederick the Great in Spring 1761, also indicating that a sizeable number of musicians could be assembled.

Extracts of stage works and oratoriosFootnote 112

According to the obituary, Klipfel made frequent trips to Dresden at carnival time in order to see the latest operas, returning to Meissen with scores of the ones he had just heard.Footnote 113 Klipfel's collection bears witness to this activity and there are extracts, ranging from single arias and instrumental marches, to quite complete scores. If Klipfel did indeed collect most of these works soon after their performance for the Hoftheatre, they provide one of the clearest indications of chronology within the collection. Some are dated (see cover sheet for the Hasse opera above), while in other sources, the name of the singers who performed the aria is given in the score, thereby confirming the date of performance with which the score is associated. There appears to be a further attempt to add library numbers to performing parts of the opera materials (see Appendix 3), but the chronology of the works is again not reflected in the library sequence.

While the repertoire reflects that which was performed in the Hoftheatre, it appears that Klipfel has generally eschewed stage works by Italian-born composers. Thus, apart from some arias from the chamber cantata Segreto tormento by Pergolesi (Naples, 1731), all other music for the stage he collected was by German-born composers writing in an Italian style, indicating that, in general, the Italophilia displayed within the court did not automatically transfer to music lovers outside. Klipfel's collection contains extracts from La Galatea (Dresden 1746) by Johann George Schürer (c.1720–86), and extracts of three operas by C.H. Graun: Catone in Utica (premiered in Berlin in the 1743–44 season, the Klipfel copy is dated 1748); Demofoonte (1745–6 in Berlin) and Ifigenia in Aulide (1748–9). Significantly, the other 43 items are of music by Hasse, taken from operas that were given premieres as early as 1730 and as late as 1760. It is highly illuminating that Klipfel was able to acquire copies of music by Hasse so soon after its first performances in Dresden. Not only does it serve to underline the changing ‘buon gusto’ (good taste) apparent in the musicians in the environs of Dresden, particularly those without direct access to courtly life, but also the speed of transmission suggests that there was a well-oiled system for disseminating Hasse's music, presumably as a commercial enterprise. It is not certain whether this was an official courtly business or an informal, even surreptitious, activity by the court copyists.

It is in the stage works that there is the highest proportion of manuscripts in hands other than Klipfel's. To enable him to return to Meissen with copies of music of the latest opera after each carnival season, Klipfel had to count not only on professional copyists to provide such large amounts of material in a short amount of time, but he also had to purchase copies directly from the court copyists. Thus, we see that Johann Georg Kremmler (employed by the court 1733–59) is the copyist of one of the scores containing extracts from Solimano (1753) (SA 1571) and both he and Johann Gottfried Grundig (employed by the court 1733–73) are the copyists of the score containing arias from Ezio (1755) (SA 1901). Not only must it have been an expensive proposition to purchase a score of an opera, the scale of the work meant that more than one copyist might be engaged to complete the order.Footnote 114Solimano proved to be a popular work with more than one set of items. Another ‘supplier’ was Holstein,Footnote 115 who copied the (?complete) score of work (SA 1038) from which Klipfel copied out parts.

The earliest date Klipfel commenced collecting music is not apparent, but there is evidence to suggest that three of the earliest in Table IV – Demetrio (1740), Lucio Papirio (1742) and Antigone (1744) – were very likely copied c.1760, since they are all copied on the same Saxon paper in the hand of the Dresden-based copyist described as ‘Berlin 61’, who is also the copyist of Artaserse (1760).Footnote 116 Like a stamp collector trying to complete his set by purchasing missing items, it appears that Klipfel has commissioned copies of the highlights of works he would not have otherwise been able to collect. It would appear that Klipfel started collecting music circa 1747 when he was 20 years old, giving a possible inauguration of the Meissen Collegium Musicum to around that time.

Table IV. Sources of Hasse opera music in the Klipfel collection

| Hasse operas | Date of 1st performance in Dresden | Sing-Akademie call no. and format | Copyist |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dalisa | 17 May 1730 | SA 1348 (parts) (parts - 1 aria only) | Klipfel |

| Demetrio | 2nd version 8 Feb. 1740 | SA1474 (parts - 1 aria only) | Berlin 61 |

| Lucio Papirio | 18 January 1742 | SA 1476 (parts - 1 aria only) | Klipfel, extra vn an vlne parts / Berlin 61 all others |

| Antigono | 20 January 1744 | SA1479 (parts) | Klipfel, extra vn parts / Berlin 61 all others |

| La spartana generosa (Archidamia) | 14 June 1747 | SA 1482 (parts - 1 aria only) | Klipfel |

| Demofoonte | 2nd version 1748 | SA 1473 (parts – 1 aria) | Klipfel |

| Il natal di Giove | 7 October 1749 | SA 1079 (score - excerpts) | Dresden court copyists 1& 2 |

| Attilio Regolo | 12 January 1750 | SA 1078 (score - excerpts) | Klipfel |

| Ciro riconosciuto | 20 January 1750 | SA 1480 (parts - 1 aria only) | Klipfel |

| Ipermestra | 2nd version 7 Oct 1751 | SA 1481 (parts - 1 aria only) SA 1561 (score- 5 arias) | Klipfel Dresden copyists (f1-6) / Klipfel (f5-27) |

| Adriano in Siria | 17 January 1752 | SA 1573 (score - 2 arias only) | Dresden copyist |

| Arminio | 7 Oct 1745 / 2nd version 8 Jan 1753 | SA 1075 (parts - sinfonia and 1st aria only) | Klipfel |

| L' Eroe cinese | 7 October 1753 | SA 1483 (parts - 1 aria only) | Klipfel |

| Solimano | 5 February 1753 | SA 1577(2) (score - 1 aria only) SA 1362 (score - 13 arias) SA 1368(2) (parts - 1 aria only) SA 1570(1) (score- 2 arias only) SA 1571 (score x2 & parts- excerpts) ” SA 1038 (score- complete?) | Dresden copyist / Roellig Klipfel Stübner/Klipfel/court copyist Klipfel / Roellig Klipfel (score 1 & parts) / Kremmler (score 2) Klipfel (score), Holstein (score) |

| Artemisia | 6 February 1754 | SA 1367(1) (score- 1 aria) SA 1581 (parts – 1 aria) | Klipfel Klipfel |

| Ezio | 2nd version 1755 | SA 1568 (score- 9 arias) SA 1901 (score- arias) SA 2206 (parts- march) SA 1368(1) (score- 1 recit & aria only) | Dresden copyist Kremler/Grundig Klipfel Dresden court copyists (1&2) |

| Il re pastore | 7 October 1755 | SA 1117 (parts- 5 arias) SA 1578 (parts- 1 aria only) SA 1577(1) (score- 17 arias, 4tet chorus) | Klipfel Klipfel Dresden copyist |

| L'Olimpiade | 16 February 1756 | SA 1109 (score – incomplete 114 folios) ”(parts) SA 1572 (score - 3 arias) ”(parts) | Dresden copyist Klipfel Unknown (Berlin?) Klipfel (1756) |

| Artaserse | 1760? | SA 1475 (parts - 1 aria only) | Berlin 61 |

Part 3. Copyists in the Klipfel collection and the dating of Klipfel's handwritten copies

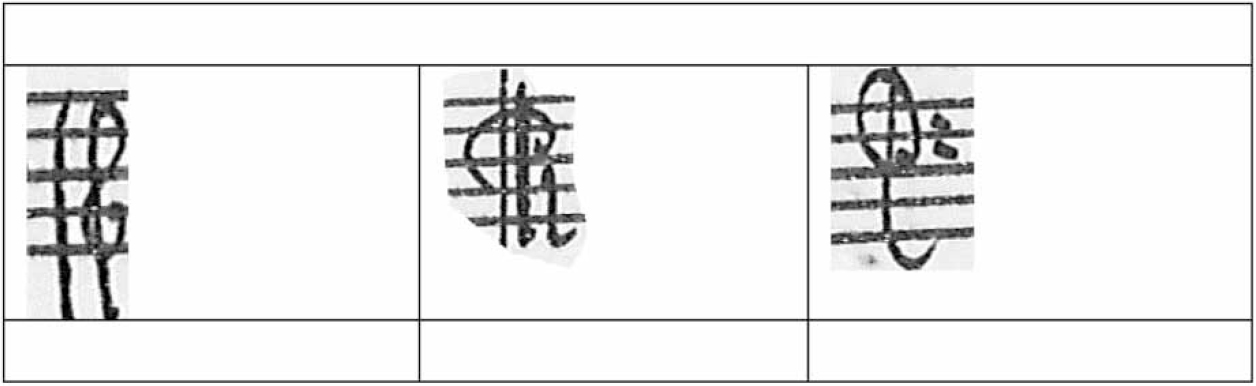

The Sing-Akademie cataloguers have given approximate dates for most items in Klipfel's former collection, but in the main have only indicated whether they believe the manuscripts pre- or post-date his move to Berlin. In this regard they have not been entirely consistent, giving both a pre- and post-1763 indication for works with the same watermark. What can be presented for the first time in this article is the discovery that Klipfel's handwriting can be used to date scores and that, from this, it is possible to make a correlation with the paper stock Klipfel used in distinct periods. Klipfel was very consistent in his drawing of clefs within certain periods of time and, by cross-checking dated works by Roellig and the copies of Hasse operas listed above, it can be determined that Klipfel adopted two distinctly different forms of the treble ‘G’ clef, changing from the ‘baroque’ clef to the modern style around 1754–5 (there was some alternation between the two types in 1754–5) (Table V). The earlier baroque style of ‘G’ clef was developed from a ‘closed’ version in c.1746–7, to an ‘open’ version in 1748–54 which, c.1748, was placed across the two lowest spaces of the stave. In addition, the bass ‘F’ clef gradually evolved c.1740–c.1760 with minor variants in the period to 1748. The pair of vertical double lines was abandoned in 1756, and it was developed into a large rounded shape that extended above the stave c.1758 before returning to a version similar to that of 1756. The ‘C’ clef remained more or less constant in style until c.1758 when it, too, was modified to a form that was consistently used from 1759 onwards.

Table V. Klipfel's clef types

| Treble | C clef | Bass | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before 1747 |  |  |  |

| 1748 |  |  |  |

| c.1748 |  |  |  |

| 1748–55 |  |  |  |

| 1754–5 |  |  |  |

| 1756– |  |  |  |

| ?1758 |  |  |  |

| ?1758–9 |  |  |  |

| 1759 |  |  |  |

| c.1760? |  |  |  |

| After 1763 |  |  |  |

From this it is then possible to ascertain that while Klipfel used certain paper types consistently between c.1747 and 1763, such as ‘ES im Falz’ (which Klipfel used only up to c.1758) and the generic ‘Saxon arms’ which covers a variety of marks,Footnote 117 some watermarks only appear on works copied within a short time-frame, sometimes as short as a year or so (such as ‘ES im Kreis’ and the ‘W’ watermarks used only in the period 1753–5) and so a number of watermarks only appear on works that can be dated 1748–54. The right-hand column of Table VI lists those watermarks which are restricted to certain time periods. A variety of different papers were used, but from 1755, fewer paper types were purchased by Klipfel, possibly since fewer were available to him as a result of privations imposed by the Seven Years’ War. The occupation by Prussian troops might also explain the use of the ‘crowned FR’ paper c.1761–2, which appears to be Prussian rather than Saxon. (Perhaps Klipfel acquired this on his trip to Berlin in 1761?). The ‘crowned eagle’ paper was used for a few scores after 1756, but is also associated with doubling parts added to works composed earlier. The ’P’ and ‘K’ watermark is used exclusively after 1763 following Klipfel's relocation to Berlin. Table VI, based upon a sample of 100 sources, including all the Roellig sources, indicates the correlation of Klipfel's clef-types and watermarks.Footnote 118

Table VI. Watermarks found on sources in Klipfel's hand

| Generic, or common to most periods | Specific to particular time periods | |

|---|---|---|

| 1747–8 | ES im Falz Saxon arms | ‘Springende Einhorn im Kreis’ Crossed swords ‘ES in circle’ |

| 1748–53 | ES im Falz Saxon arms (various, with countermarks: GHS/CHS; ‘Dresden’) | ‘Springende Einhorn im Kreis’ Anchor Crossed hammers (with countermark ‘CFS’) ‘SW in Falz’ |

| 1753–5 | ES im Falz Saxon arms (with upright lion, 1754) | ‘ES in circle’ (in 1753/54 only) Crowned ‘W’ Double-stroked ‘W’ |

| 1756–8 | ES im Falz Saxon arms (with countermark: ICF) | ‘ES doppelstrichig’, with and without circle (1756) Crossed swords Crossed swords, crowned between two branches Crowned (double) eagle with sceptre and sword |

| 1759–63 | Saxon arms | Crowned lily-shield Crowned ‘FR’ |

| 1763– | - | ‘P’ & ‘K’ |

With the change from the older form of treble clef to the modern style, the changes to the form of the F clef found in sources c.1758–9, and the C clef from 1759, it appears that Klipfel adopts forms of clef that are more similar to those used by Roellig (Figure 3). A further change in style can be observed in the production of scores; in the last year or so in Meissen, Klipfel changed from a portrait format to a landscape format, one he then used exclusively in Berlin.

Figure 3. Rollig's autograph clef types in 1754 (from SA 1426).

The significant breakthrough in dating Klipfel's pre-1763 scores to within a few years makes it possible to date more firmly works by a number of other composers, for whom no other means of dating is possible, particularly composers of the Dresden circle such as J.C. Roellig (b.1716); G. Gebel (1709–53); J.G. Harrer (1703–55); C.J. Fehre (1718–72) and J.A. Hiller (1728–1804), and to refine the dating of works by other composers such as C.F. Abel (1723–87) and the Graun brothers. The dating of Klipfel's handwriting also highlights how extra string parts have been added to sets of parts at a later date, indicating changes to the size of the performing group (see comments below). It is also clear that library covers occasionally post-date the sets of parts; there is a batch of works (SA 2334, 3225, 3230, 3231 and 3233) on ‘ES im Falz’ paper where the handwriting on the cover is post-1754 while the clefs in music are all of the older style from 1748–54.

While Klipfel took on the role of copyist for the Collegium Musicum in its early phase to save on costs, as time went on, and funding for the group perhaps became more secure, Klipfel increasingly relied on other copyists (Table VII). There are a number of scribes in the Meissen-Dresden area with whom Klipfel appears to have interacted.Footnote 119 It is not always clear whether these were independent collectors or merely copyists engaged by Klipfel, though the presence of names in the title page tends to suggest the former, while the anonymous copyists tend be the latter. Some of these copyists may have been members of the Collegium Musicum, while others were freelance musicians in Dresden.

Table VII. A summary of the copyists in the Klipfel collection, their location and the genre in which they worked

| Location | Symphony | Concerto | Partitas | Opera extracts | Choral/vocal | Keyboard |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berlin | Itzig 9 (/Itzig 8) | ?Holstein | ‘Berlin copyist’ | |||

| Berlin 38 | ‘Berlin copyist’ | SA 15 | ||||

| Berlin 46 | Thamm | |||||

| Berlin copyist | ||||||

| Thulemeier III | ||||||

| Patzig, J. A. | ||||||

| Baumann, F. | ||||||

| Zelter | ||||||

| Dresden | Roellig | Roellig | Roellig | Roellig | Roellig | Roellig |

| Oehm, H. | ||||||

| Berlin 61 | Berlin 61 | |||||

| ‘copyist of dresden’ | ‘copyist of Dresden’ | ‘copyist of Dresden’ | ‘Dresden court copyists 1 & 2’ | ‘copyist of Dresden’ | ||

| Kremler/Grundig | ||||||

| Meissen | Klipfel | Klipfel | Klipfel | Klipfel | Klipfel | Klipfel |

| Stubner, J.F. | Stubner, J.F. | Stubner, J.F. | Stubner, J.F. | |||

| Otto, J.F.E. | Otto, J.F.E. | |||||

| SA 519 | SA 521 | |||||

| SA 522 | SA 522 | SA 522 | SA 105 | |||

| SA 550 | SA 574 | SA 96 | ||||

| Other | ‘(monogram CFH?)’ | Bach, J.C. |

Meissen copyists

The score of a Graun symphony (SA 2168)Footnote 120 dated 1752 is presumed to have come into Klipfel's possession from the collection of Heinrich Oehm; Klipfel later created a set of parts from the score (SA 2167). J.F.E. Otto is another copyist from the Meissen-Dresden area, identified by his written signature on SA 2394. Otto provided scores of three partitas by Dresden composers, one each by Georg Gebel, J.C. Roellig and Harrer,Footnote 121 and he also provided the violone parts to the set otherwise copied by Klipfel for Graun's Sinfonia to Demofoonte. Footnote 122