1. Introduction

It is a sad fact that physical violence and, as a subtype, the corporal punishment of children and juveniles, practised by parents and other guardians, schools and clergy in both Europe and North America, have been part of our ‘Western’, i.e. Christian, cultural heritage, not to mention other world-cultures. I myself am old enough to remember the various common practices of physical violence used on children in the 1950s. At school in Germany, caning and face-slapping were officially tolerated and quite common, applied as a kind of educational instrument, sometimes even to 17-year-olds. In state-run schools of the United Kingdom, corporal punishment was politically banned only in 1986. Private schools followed suit from 1998 (England and Wales) to 2003 (Northern Ireland) (Country report for UK, 2015). In the United States, corporal punishment is still lawful in 19 states, in both public and private schools (Country report for USA, 2016).

Corporal punishment has been the subject of a large number of sociological and educational studies (e.g. the historical survey by Geltner, Reference Geltner2015). The internet abounds in mostly sensationalist and voyeuristic videos of (historical) caning, whipping and spanking, taken mainly from movies. The issue of beating children has recently been discussed in Western countries within the more general context of child abuse, both in the form of physical violence and sexual abuse – cf., e.g. in Germany, the ill-treatment of the Regensburger Domspatzen, the renowned choir boys, by their teachers in the secondary school run by the Catholic Church in Regensburg (Bavaria). Certainly the two types, corporal punishment and sexual abuse, have often been connected in practice, but they have to be kept apart in principle. Sexual abuse, particularly of children, has always been considered a crime by most people. But physical violence, though unacceptable from a present standpoint, was, up to recently, not only excused, but even defended as a means of education. In a wider and political context, it was a tool of the more powerful to dominate the weaker members of society, thus maintaining the ‘God-given’ social order. This general attitude affected children as much as women, slaves and domestic animals.

This paper is, however, not concerned with the political, cultural and historical dimensions of physical violence. Instead, it suggests focusing on the linguistic expression of violence in dialect as used by ordinary people, at a time when regional dialect was still normal (1700 to 1904). This period of selection results from the textual basis of this paper, the English Dialect Dictionary (EDD; Wright 1898-1905), compiled by Joseph Wright, in its newly available shape of EDD Online (published by Manfred Markus within an Innsbruck project in 2016: eddonline-proj@uibk.ac.at). Linguistic violence, for example, colloquialisms of the type ‘shut your face, or I'll knock your head off’, were, of course, not limited to the treatment of children, but this paper will focus on them as a typical group of victims and investigate the different expressions of corporal punishment, here for short referred to as the semantic field [BEATING] – other forms of verbal violence, such as swearing, are excluded. My attitude in tracing a sub-section of formerly tolerated forms of violence is neither nostalgic nor apologetic, but descriptive, one of the questions being whether rude language announcing violence was simply the correlative of violence in deeds within the 18th and 19th centuries or also a relic of the perennial ‘game’ of threats, so-called fliting, known from Germanic heroic poetry (cf. Clover Reference Clover1980: 453; on Old English poetry and Chaucer, cf. Jucker & Taavitsainen, Reference Jucker and Taavitsainen2000), and also from historical play fighting of puppies and children/adolescents (cf. Pellis & Pellis, Reference Pellis and Pellis2009: ch. 2). In any case, linguistic violence in English dialects is ubiquitous, as will be shown in the following analysis. It is, thus, a phenomenon that, unlike corporal punishment as a sociological topic, has remained largely unnoticed.

2. Towards a quantitative survey of the use of terms for [BEATING]

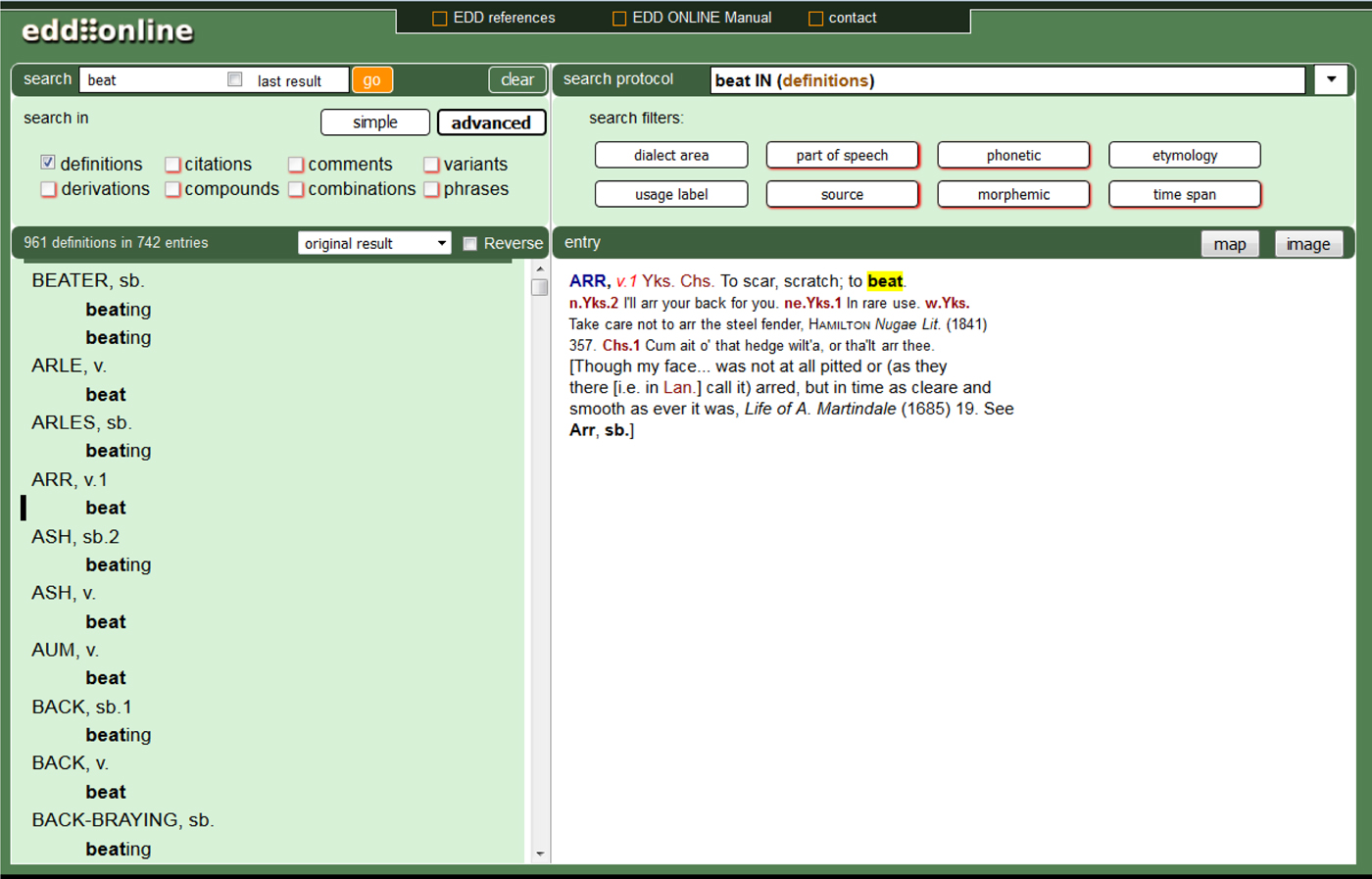

For finding dialectal terms within the lexical field [BEATING] (in its wider sense of physical ill-treatment), EDD Online provides a number of options (see the Manual by Markus, Reference Markus2017, provided on the website: eddonline-proj.uibk.ac.at). The option closest at hand is the parameter definitions. A search, for example, for the (implicitly truncated) string beat as a term of definition provides 961 matches. By the same token, dozens of other synonymous or hyponymous verbs, found by serendipity, testify to the wealth of dialectal vocabulary pivoting on [BEATING]. They range from to blow, strike and push to to knock, scratch and whip, with the first 33 most frequent verbs providing access to more than 5,000 passages. In answer to this quantitative challenge, Figure 1 focuses on the retrieval list of the keyword beat alone and suggests a manual close-up look at the 961 findings – or, rather, at the first ten samples incidentally leading the list.

Figure 1. Beginning of retrieval list for beat as a string of definitions

The very first of the 961 findings, BEATER, already turns out to be invalid in that it refers to various tools for beating objects rather than to humans practising physical violence. So this is a warning right away for users not to expect all the findings to be matches. However, the words then following are mostly valid hits. ARLE, in one of its senses, is defined as ‘to beat severely’ and attributed to Banffshire. ARLES, etymologically explained to be a cognate of Lat. argentum (in the sense of a silver tip [arles penny]), was used in parts of Scotland within the phrase to give any one his arles, meaning ‘to give any one his deserts’ and ‘applied to a beating’. Wright adds two quotations:

Inv. To gie ane his arles (H.E.F.). Bnff.1 A'll gee ye yir arles, my boy, gehn ye dinna haud yir tung.

[in standard English: Inv. To give sb. his ‘arles’ (H.E.F.). Bnff.1 I'll give you your ‘arles’, my boy, if you do not hold your tongue.]

While this example of the reference to beating formally shows the role of phrases in our context and, semantically, some strategy of camouflage and ironical euphemism, the next one (ASH) reveals metonymical use of the esh/ash rod or cane ‘being the instrument used by the castigator’, as Wright quotes from one of his sources. An equally metonymical transfer from the beating itself to the tool used for that purpose is also at the root of the verb AUM, which literally means ‘To dress or prepare skins or paper with alum’. A derivation AUMAN (for Auming) is likewise concerned. The figurative meaning of aum, via ‘tan a person's hide’, is ‘to thrash, beat soundly’. The metonymical transfer presupposes the knowledge of how the tanning of deer skin was practised, namely by strong beating movements. This historical context was probably still transparent to 19th century people, but the next sample in our list of Figure 1, BACK, both as a noun and a verb, suggests that the former transparency of the figurative transfer may have been lost: back as a noun is included in the form of the compounds back - slamming and back - sweat. For the former, Wright lengthily quotes his source:

Lan. In back-slamming the offender is swung against a door, or wall, by two or more persons, who hold him, face upwards, by the arms and legs, and thus turn him into a sort of battering ram, Harland & Wilkinson Leg. (1873) 175.

Back - sweat is defined as ‘the warmth caused by beating the back’. And the verb to back is simply defined – in allusion to the back of the beaten person – as ‘to beat, thrash’. BACK-BRAYING, the last sample in Figure 1, goes in the same direction, with bray literally meaning (in Ireland and all northern English counties to Lancashire) ‘to beat; to bruise or grind to powder’.

These few eclectic examples, selected simply by the alphabetic principle, may suffice to draw some intermediary methodological conclusions:

(1) Notwithstanding occasional invalid findings, the quantity of valid samples is overwhelming, and would be even more so if we had included the quotations in each case of our analysis. To bray, for example, is illustrated by a large number of text samples, most of which target a human object. For lack of space they have not been quoted here, but they generally encourage an analysis of Wright's quotations in addition to his definitions.

(2) The threatening pattern (of the type do so and so, or I'll beat you) is one of the most striking formal markers that we can trace. This paper will focus on this pattern in the following section.

(3) The style of many expressions is marked by a metaphorical and/or metonymical indirectness, often resulting in a euphemistic non-transparency. To throw some light on the idiomatic imagery of the expressions, we will discuss their main circumstantial factors: typical victims and protagonists of violent treatment, targets and tools of castigation, and typical grades of beating.

(4) The ubiquity and, in many cases, brutality of obviously common beating practices cannot be overlooked. However, clauses such as Aa'll bray the sowl oot o’ ye could also be due to verbal hyperbole used as part of the perennial threatening ‘game’, in other words, of the ritualistic demonstration of (physical) power.

3. The threatening pattern

One can find dozens of examples of the threatening pattern from the dictionary's blocks of ‘citations’ (= quotations). Here are three of them (emphasis mine, MM):

n.Lin.1 s.Lin. Now behaäve yersen , or I'll give ye a clink about y'r head (T.H.R.)

Cor.1 Stop thy grizzling [giggling], or I'll gi’ ‘ee a clout shall make ‘ee laugh the wrong side of thy mouth

Oxf. You stop that, or I'll lump you (G.O.)

As the three highlighted dialect words of violence, with their specific meaning and connotations, are unpredictable, a search for them has to focus on the string ‘or I'll’. This search mode in the citations, admittedly, implies a few problems. One of them is that one must reckon with spelling variation, for example, or A'll instead of or I'll, or with lexical variation generally. For example, the strings else I and afore/avore I also provide some matches.

Irrespective of such formal barriers of retrieval, the list of clauses of the or I'll-pattern, with an output of 74 samples altogether, is sufficiently long to allow conclusions about the favourite verbs in this context

Formally, the pattern do so and so, or I'll do so and so with you is, in the great majority of cases, represented by or I'll. There are, however, three cases which start the warning I'll/Ah'll directly, with the imperative to be found in a previous sentence. In another three cases, the pattern is slightly changed: do so and so, before I beat you. Moreover, the list has five samples of warnings introduced by else, and one with the conditioning subordinate clause if.

In addition to this syntactic variation there is a clear tendency towards stylistic modification. The act of corporal violence is often not addressed directly, but with an obvious pleasure taken in circumscription, sometimes with metaphorical implications. Thus, the first sample is an allusion to the tailor's taking his customer's measures with the measuring stick. Four samples equally allude (by euphemisms) to a tailor's activity (trim your laced jacket/measure you for a new jacket). Other examples are based on non-transparent or – from a present point of view – far-fetched metaphors. Or I'll pin a dish -cloot to thy̆ tail [said to men and boys in the kitchen] obviously roots in the idea that men and boys should not be in the kitchen and would otherwise be driven out with a dish-cloth fixed to their ‘tails’ (slang word for ‘penis’). Another sample (or I'll rundown an yes, in the context of Wright's full quotation, makes use of an equally brutal method of getting rid of somebody. The string yes, on closer inspection, turns out to be a variant of easse, which stands for a ‘large earthworm’ as used as a bait for fishing (see EDD entry EASSE). In a freely modernised translation the full sentence behind the quoted clause, then, is: ‘Piss off, or I'll run my fish-hook down your throat.’ There is another example of this bizarre concept of daily brutality, borrowed from the language of anglers: or I'll maybe ding [knock] the neb [tip] o' my heuk [hook] into them.

Such are examples of verbal violence which certainly cannot fully be taken literally, but simply reveal the joy of drastic exaggeration. This stylistic feature also applies for many other samples of a list too long to be quoted here, be it the idea of breaking somebody's head (3 passages), ‘pulverising’ somebody (1x), breaking somebody's neck (2x), knocking out somebody's brains (3x), cutting off somebody's tongue (1x), gouging out somebody's eyes (1x), cutting somebody to pieces (1x) or beating someone's head off (1x).

In other samples, the hyperbole of expression consists in the exaggerated temporal extension of the ill-treatment in the form of a subordinate clause of time: for example, or I'll leather you as long as I can stan' oher you (entry OBBUT). Another common case is that of the verb itself being hyperbolic: shift (2x); shot (Stand, or I'll shot ye (entry SHOOT); bray [‘beat to powder’]; mun [‘skin’], kill, etc.

Metaphorical or not, hyperbolic or not – the common feature of the quotations as a whole is the obvious joy of variation, which the different verbs of definition used by Wright, discussed above, already testified to. [BEATING] was – sadly to say – part of the common practice or ‘game’ of violence, taken as a God-given principle particularly in the 19th century. While the character of a game would imply that words were not always meant completely seriously, the victim could never be sure. The kill example just mentioned may illustrate this ambivalence. On closer inspection, it does not refer to human beings at all, nor is it intended as a metaphor for more moderate ill-treatment, but, addressed to bugs or beetles by children, has probably to be interpreted literally. The addressee is a black -bob (=‘black-beetle’), and children, if they announce to ‘kill’ a beetle, probably mean it.

Notwithstanding such exceptional examples, the general conclusion for this section is that verbal threats of the pattern do so and so, or I'll beat/punish you were part of LModE everyday popular culture. The used expressions are full of hyperbole, as well as metaphorical and metonymical indirectness, and they abound in brutality. But the brutality is a verbal one and is, like death and murder in present-day TV thrillers, also part of the game. In order to judge to what extent the brutality is simply a reflection of everyday life or a verbal game, as suggested by the hyper-rudeness and indirectness of the expressions and by the general pleasure in variation, one has to find out the degree of idiomaticity involved, focusing on some of the circumstantial factors of the ‘beating scenario’.

4. Circumstantial factors of the ‘beating scenario’

The ‘beating scenario’ in dialects has conventional victims and characteristic protagonists. Boys are clearly the most typical victims – boy occurs 638 times as a collocate of beat, to be found via the ‘last-result’ mode of EDD Online. Some retrievals suggest that boys are both victims and offenders. Thus, the verb to buff means ‘a blow given by a boy to provoke another to fight’ (BUFF, v.2). This role of boys would be in line with their stereotypically reckless or rowdy character (‘boys will be boys’).

There are no references to girls or to women in this context. However, wife provides quite a few matches (ASH; BAMMEL; BANG, BRAY, etc.) – wife-beating was not uncommon with Victorian working classes (cf. Keating, Reference Keating1971: 174–5). Some of the EDD matches, however, reveal that beating one's wife was – at least by some - considered unacceptable, as is suggested by the following habit. The verb to ran -dan was used in parts of Yorkshire and in neighbouring counties in the sense of making noise ‘with rough singing, and the beating of pots and pans, at the house of the man who has beaten his wife’. The compound rantipole riding is used similarly, expressing ‘a method of punishment inflicted upon a man who beats his wife’. Interestingly enough, there are passages testifying to the opposite roles of husband and wife. In Scotland, the phrase it's a sour reek was used for a wife beating her husband, in allusion to the husband's evasive answer outside the house when asked by people for the reason of his tears. Sour reek refers to the acidic odour, e.g. of onions, that makes your eyes water with tears. Another example of beaten husbands is, among several quotations, BANG, v.: Ayr. And aft my wife she bang'd me.

Not surprisingly, the string child* also sometimes co-occurs with beat* in EDD definitions. FLUX, HONE, PAT, RATTLE, SCALE and SCOUR turn out to be valid findings. For the rest, there are occasional references to youngster (COLT) and person (DING), and there is a special term for somebody ‘beaten by a person younger than oneself’ (see boy -beat in BOY) – but these are exceptional cases, with boys being the default victims.

Who or what are the most typical people and institutions practising corporal punishment? Not surprisingly (at least to readers who remember Thomas Hughes’ Tom Brown's School-Days), a frequent collocate or at least connotation of beat is school, with twenty entries of co-occurrence. An example is the verb to bombaste:

BUMBASTE, v. e.An.1 Nrf.1 Suf.1 Dev.1 To beat soundly, severly, esp. to inflict school discipline.

Synonyms of this word are to bumbrush (Norfolk and Suffolk), to cob(b (Sc., Irel.), to cog, as well as the noun cogging (Northumbria and Yorkshire), to cosh (‘a caning at school’, Norfolk, Suffolk, Warwickshire), and to cut into, which was used ‘at Winchester School to hit with a ground ash’.

Apart from school, no other typical collocates referring to educational institutions can be found. Neither teachers nor parents nor clergy are hardly ever mentioned as ‘beaters’. In none of the definitions or quotations is there a tone of blaming somebody for practising castigation – it was obviously commonly accepted, so much so that the reference to a public whipping post (braying steeak [variant of steek ‘stake or pole’]) should not take us by surprise.

As regards the targets and tools of beating, some of the terms for the victim's body parts concerned are particularly favoured to be verbalised. The posteriors are the main candidate, as in Doup -skelper, which, in some areas of Scotland, was the term of a schoolmaster ‘who strikes or beats on the buttocks’. Also in Scotland, to horse was used metaphorically for ‘striking [sb.’s … ] buttocks on a stone’ (see HORSE, sb. and v.). COB(B was generally used for beating or striking ‘on the posteriors with anything flat or with the knee’ (COBB, 1.). Skin, hide and fingers are also occasional collocates of beating (cf. DERSE, AUM, EDDER; PAY, 3.), as are the victim's bones (see RADDLE sb.1, v.1; BANG). In general, bones are more often threatened to be ‘broken’ than ‘beaten’ (cf. COME: ‘Ere I come at ye … An’ brak’ yer lazy banes’). The bones/banes passages, however, also reveal that a fuzzily allusive and metaphorical style is more typical than referential denotative precision. Instead of being ‘beaten’, the victims, or the victim's bones or skin or ‘back and side’ are often ‘paid’ – in view of the castigator's self-righteous belief that the victim deserved the penalty. Here is a typical example of this metaphorical use of to pay: ‘There I paid her baith back and side Till a’ her banes play'd clatter’ (PAY, v., sb.). 20-odd further examples of this type confirm the common usage of to pay in the sense of beating, as does the formation of a derivation payment (in dialect: pemmint ‘a thrashing’).

Some other terms imply the ‘head or face’ (DOUSE, v.1 and n.1) or the ears (lugs; cf. BAZZ, BUFF, CLINK, CLOUT, etc.) to be the object of castigation. COBNOBBLE was a term in Cheshire and Derbyshire for a ‘knock on the head’, to be found in Gloucestershire in the form of CORNOBBLE. DUNCH was widely used for a ‘push against or butt with the head’, also with a foot or elbow (also cf. HIKE).

As in this latter case, many other terms imply the instrument of ill-treatment applied to the victim, for example, in the very specific case of the verb MOB, v.1 (East Yorkshire), which, as a tool for a delinquent schoolboy, connotes either caps or ‘eggs, not always fresh-laid’. The eggs, however, were only used on a special day, the 29th of May (called Mobbing Day). Teachers more commonly used a leather strap (cf. THONG) and a cane/stick (see ASH, COSH, LOWDER, PATTER, HAMMER), or, most frequently, simply the hand or fist (see CLATTER, DAD, SCUD; FIST, BANG, KNEVELL, MUMP, NEVEL, NISSLE, PELK, PLUG, PUNCE, SCRUFT, SCRAM, THUD and THUMP), but sometimes also a flail (cf. FLACK, BUMP, FLACK, SWIPPLE) or even a spade (BAT) or cudgel (CRUNT, NAUP).

As mentioned above, the cane or rod of castigation is often referred to metonymically, by the term for the wood that these instruments of ‘education’ were usually made of. Ash/esh, hazel and birch obviously provided the best material. One can, therefore, find quite a number of characteristic quotations around these three types of wood suggesting their castigating function. Among the 20 citations with ash (plus three for esh), the following from Warwickshire may stand for the rest: ‘An ash-plant [plant = metonymy for ‘stick’] is an article that no well-furnished farm-house and few schoolmasters would be without.’ (ASH, sb.2). Birch- and hazel-rods or -sticks, while also used in various other senses, served the same purpose: ‘the birch was doing duty’, one of the quotations unambiguously tells us, and in the entry LINE (in the sense of ‘to thrash’) a warning is quoted: ‘I'll line thy birches vor thee when I catch thee’. Hazel is the most common of the three wood-specific expressions, with 23 matches in a search for this word within the context of beat. One of the (quoted) definitions given in the entry HAZEL itself is revealing enough: ‘To beat with a stick, not necessarily a “hazel” one.’ Obviously, hazel-sticks were so common a tool for beating that the material was eponymically transferred to all kinds of beating sticks.

Hazel -broth (‘a flogging with a hazel-stick’) is particularly typical, in three ways: (1) it refers to the type of wood most frequently used for a beating stick; (2) it is one of many compounds that imply the meaning of beating and that have widely been disregarded in this paper in order to keep the lists of examples moderately short (the same holds true for derivations and phrases, such as oil of hazel ‘thrashing’); and (3) it is implicitly metonymical and clearly metaphorical: hazel stands for hazel -stick (metonymy) and broth, literally the well-known soup (with meat etc. in it), is a metaphor of the substantial ‘contents’ of the castigation with a hazel stick or rod.

The circumstantial factors of beating also include its gradability. Combining beat as a term of definition with the truncated string *ly within the quotations, the list of words, mostly adverbs, then found can optionally be arranged alphabetically (Figure 2). The user can then easily select the findings that collocate with the verb to beat.

Figure 2. ‘Last-result’ search for –ly-adverbs in citations (after search for beat in definitions), presented alphabetically in the ‘column-2’ mode

Figure 2 may suffice to show the enormous amount of adverbs available in the cotext of beating. We can, thus, trace heartily (I'll leather you heartily), neatly (4), severely (3), sharply (5), soundly/soondly (8), violently (4), and various others. Neatly (e.g. in LOWDER), nicely (in FETTLE), purely (collocating with BENSIL) and soundly (‘his wife clours him soundly enough’, in CLOUR) enhance the impression that positive adverbs predominate, as is confirmed by the frequent occurrence of the adjective good and the adverb well in phrases of beating. For example, a good leathering was a common idiom (see LEATHER; also cf. AUM: he aalum'd me reet weel for it). Wright himself, in his own definitions of the passages at issue, regularly uses equally positive adjectives, such as good, and adverbs, such as soundly, thus giving evidence of the general attitude of his time. From a present point of view, the positive adverbs in combination with verbs of beating are typical 19th-century euphemistic misnomers.

5. Metaphors and metonymies

The assumption that dialect speakers would generally ‘call a spade a spade’, cannot be confirmed in the face of the ubiquitous metaphors and metonymies in the semantic field [BEATING]. We have had many examples of metaphorical and metonymical indirectness in previous quotations, from those of the tools of beating and beating as payment to those of the thrashing (= treshing, cf. Concise Oxford Dictionary, Reference Fowler and Fowler1951) of corn standing for the beating itself, and from tailoring to the hiding and tanning crafts as metaphorical ‘vehicles’. The indirectness is sometimes carried so far that the expressions are chiffre-like idioms, transparent only for the initiated.

Hazel, a most prominent metonymy (for hazel - stick), may serve as an example. Surprisingly, beating and thrashing were often associated or connoted with oil. Expressions such as oil of hazel, also oil of birch, oil of oak and oil of strap, enhance the general validity of this notion (see HAZEL, OIL). Two quotations may stand for more than a dozen:

Gie their hides a noble curry Wi’ oil of aik (OIL, 9.) (‘oil of oak’)

‘The oil of hazel’ has been famous in all ages as an approved application to the backs of obstinate dames, and mischievous, ill-contrived boys. (HAZEL, sb., v. 6.)

The motivation behind this remarkable concept of OIL, as a chiffre for beating, can hardly be derived from the ‘oil … contained in a green hazel rod … to be the efficacious element in a sound drubbing’ (OED on oil of hazel). This seems too simple an explanation in the face of the different other types of wood mentioned above, which are less ‘oily’, and above all in view of the ‘oil of strap’. Why should a (leather) strap used for a ‘sound drubbing’ be oily, and if so, efficacious? Oils, it is true, have always been used for body treatments. But an additional, if not the main motivation of the concept of oil as a chiffre of beating, in my view, comes from religion and may be clearer in the following quotations, which direct our attention to anoint rather than its collocate oil:

I will oint thy back with hazel oil if I catch thee (OINT, v.)

he is said to be ointit (OINT, v.)

Maister's nointed me to-day for talkin in class (ANOINT, 1.)

Oint is, of course, an aphaeretic form of anoint. The EDD has lemmatised, in addition to this verb ANOINT, three derivations: ANOINTED, ANOINTER, and ANOINTING (also cf. the OED). All these words have very negative meanings – as opposed to the core meaning of the verb to anoint: ‘apply ointment, oil, to (esp. as religious ceremony at baptism or on consecration as priest or king)’ (Concise Oxford Dictionary, Reference Fowler and Fowler1951; cf. ‘the Lord's anointed’ in a well-known 17th-century folk-song, ‘The Vicar of Bray’, in The New National Song Book, 19). Anoint (or oint, or preferably the aphetic form in between, noint) was, thus, surrounded by other members of the word family, with religious connotations in all cases. Given this background, it seems fair to assume that both anoint and oil, as a collocational pair, developed their metaphorical meaning of beating due to a deeply-rooted motivation of sacrilege and blasphemy – the same motivation that is common in swearing. We of the 21st century may have to be reminded that the four evangelists alike describe Jesus to have been anointed with oil. In the face of the still fundamentally religious attitude of the 19th century, the reference to beating as ‘oiling’ or ‘anointing’ is partly a euphemism and partly a sacrilege, but hardly botanically motivated. The OED's over-subtle citation of the ‘oil … contained in a green hazel rod’ seems far-fetched.

Sacrilege and disrespect for what is sacrosanct to others, to the extent of bizarre concepts, also seem the motivation of some other metaphors expressing corporal castigation. For example, the body of a beaten person is called ‘bone-cart’, especially in the phrases to rattle, bang, or sharpen the bone - cart. Bone does not need any explanation. But cart? It seems fair to assume a vague allusion to the hearse here. Sentences such as ‘Ah'll sharpen thy beean-cart for thee, if thou doesn't be off’ are, then, one of these big-mouthed threats of ‘killing’ the victim that we have found earlier. Sharpen is translated in another entry of the EDD as ‘to stir up to greater speed’ (see SHARPEN).

As against such sophisticated examples of blasphemy and disrespect, some other metaphors for castigation have less a semantic motivation or only a rudimentary one, but seem to be superficially based on sound effect (alliteration) and are, thus, a stylistic means of emphasis. To beat to bun - bread is an example of this type. Bun - bread was, according to the EDD, not otherwise used in Late Modern English, though BUN alone (sb.4) is defined as ‘a small loaf of bread’. While it does not make too much semantic sense to ‘beat a person to a small loaf of bread’, the triple alliteration in the expression is certainly apt to highlight the phrase formally.

In between these extremes – sophisticated metaphorisation and mere jingling of sounds – a large number of more or less transparent metaphors and metonymies can be found. Here is a small collection of examples from the lexical field of whipping, with whip used as a defining search string:

I thrashed the boy and sent him to the cooling stone [‘a stone in or near the school, on which the boy, who has been whipped, is sent to cool himself’] [COOLING-STONE]

Much better than knocking him down, or even co-hiding him. [to cow-hide = ‘to flog with a heavy whip’] [COW, sb.1]

to edder ‘to lash with a whip’ [edder = ‘a long, pliant stick or rod made of hazel, ozier, & c.’] [EDDER, sb., v.]

to fan ‘To whip, beat, punish’ [FAN, sb., v.]

To fan – to stay with the last example – was probably motivated metonymically by the fact that the term was primarily used for winnowing (fanning) corn, with the chaff blown off from the corn. This work was closely connected with threshing corn, so that the metaphorical meaning of threshing/thrashing could metonymically pass over to fanning [FAN, sb., v.].

This last example also illustrates the general tendency of some terms of beating to be not only obscure, but at the same time also euphemistic. In the entry WHY-I the primary meaning is given: ‘To cry out like a whipped dog’. The ‘why-me’ sense was obviously not understood by everybody, so that the folk-etymological spelling why - eye was also used. It is thus that the phrase to give one/sb. why - eye ‘to give sb. a good beating’ is both non-transparent and euphemistic.

6. Playful beating

This paper has so far disregarded playful beating practices, as I myself experienced them at the age of 8 and 9 in a country school around 1950. I was, for example, confronted with the common practice of a playful heavy slapping on each other's behind. This was one of the ‘sports’ in winter breaks, practised mainly by the pubescent 12 to 14-year-olds.

Combining beat with the catchwords game and play leads to 132 and 63 definitions respectively. One could further shrink these figures to be more reliable by adding boy as an additional search term. On checking the findings of beat + game + boy in combination, with 23 matches, one finds, for example, the following expressions:

Buck i't'neuks, phr. a rude game among boys (basic meaning of BUCK: a smart blow on the head)

Cobbing-match, sb. a school game in which two boys are held by the legs and arms and bumped against a tree (basic meaning of cobbin: beating, thrashing, schoolboy's punishment)

Coggings: a boys game (basic meaning of coggin: a thrashing)

Mothers also beat their children ‘in playful reproof’ (see BAT, v.1.), but, as the quotations suggest, above all boys beat each other non-seriously (also cf. HUM, 7.; INCH, sb.1, v. 4.). Tentative searches with blow instead of beat as a semantic marker, with the other parameters unchanged, provide Slap - of - the - ear (‘a rough game’), and a few other examples of playful beating. It must be admitted that many ‘games’, even where some beating is involved, on closer inspection turn out to be harmless ones (e.g. SCAT, 8.).

Familiar games, however, are certainly only part of the playfulness of beating. The entertainment works on a deeper level. The excessive verbosity and enormous stylistic variation concerning beating, the hyperboles, the inventiveness of metaphors, the semantic elusiveness of the idioms – all testify to a basic semi-seriousness in matters of physical violence. The role of this attitude in Victorian Britain is enhanced by the fact that violence was not only a considerable part of domestic life (see Keating, Reference Keating1971: 177–84, 194–5), but also of popular entertainment (cf. Dodenhoff, Reference Dodenhoff2008; Crone, Reference Crone2012). This ambivalence also affects the verbal manifestations of beating practices. While they reflect the ‘unparalleled brutality’ in Victorian society, particularly of lower-class men (Dodenhoff, Reference Dodenhoff2008: 2, quoting Cobbe, Reference Cobbe and Jump1999), the juggling with words of that lexical field testifies to the all-pervasive let's-pretend attitude motivating the threats and big-mouthed announcements of Late Modern English dialect speakers.

7. Summary and Outlook

EDD Online allows for an empirically (corpus-linguistically) based analysis of the lexical field of corporal punishment. The topic traces a well-known common practice of our Western culture in the past. Exerted on the weaker members of society and preferably practised by its stronger ones, particularly in the working classes, physical violence, hand in hand with the verbal expression of it, was no exception in social behaviour, but the rule. The linguistic aspect of this, like dialect semantics in general, has been grossly neglected by research.

Trying to help fill this gap, this paper is an attempt to take the language of ‘the people’ seriously. In the dialect speech of the 18th and 19th centuries, physical violence was expressed in many ways. No matter which keyword of definition we choose, the number of matches is overwhelming, over 5,000 altogether on the basis of only the 33 most frequent semantic keywords. Hoping to encourage future in-depth investigations, this paper could only selectively refer to some of the aspects involved. Syntactically and in terms of word formation, the expressions are often phrases, derivations or compounds rather than headwords, so that they have to be retrieved from the entries in most cases, with EDD Online being very helpful for this task. Semantically, we could only see the ‘tip of the iceberg’, for example, concerning the use of hazel, birch etc., i.e. of the types of ‘tools’ instead of the beating itself. It seems fair to interpret these examples as evidence of the often euphemistic and camouflaging nature of many expressions. In line with this implicit intention involved in some of the words and phrases, many of them have turned out to be based on metaphorical and/or metonymical transfer, visible, for example, in to tan sb.’s hide, one of many expressions borrowed from a common craft (and one which has made it into present-day standard English as well).

A glimpse at a block of quotations, as they are listed in large numbers in the EDD, has also revealed the brutality of many expressions of corporal violence (such as Aa'll bray the sowl oot o’ ye), but also the tendency towards occasional, and then only partly serious, hyperbole. One of the formal correlatives of hyperbole is the formulaic expression of the type ‘do so and so, or I'll beat you’. The radical manifestations of this formula are obviously frequent.

Trying to define typical patterns within the lexical field of [BEATING], this paper has discovered boys to be the most typical victims and schools to be the most common setting of corporal violence, with certain (positive) adverbs, such as soundly, as typical modifiers, and hand and cane as typical tools of beating. The main characteristic, however, is the enormous joy of – often hyperbolically playful – stylistic variation. The paper's analysis concludes with the confirmation that rude non-serious beating or fighting and its verbalisation had a more important role than people of today, used to rules of politeness and political correctness, are ready to assume.

A ‘by-product’ of this paper has been to throw light on the enormous potential of EDD Online. With the sophisticated parameters of its interface, it will encourage in-depth studies of many issues, among these of specific forms of violent behaviour, and of the specific dialectal areas to which these forms can be attributed.

MANFRED MARKUS is a Full Professor Emeritus of English linguistics and mediaeval English literature at the University of Innsbruck. He has over a hundred publications on his record. With a background in English and American literature, he has, for the last thirty years, focussed on contrastive linguistics, historical English, corpus linguistics and English dialectology. He has compiled several corpora, among these the Innsbruck Corpus of Middle English Prose and the Innsbruck Letter Corpus 1386 to 1699. In 2016, he launched a digitised version (2.0) of Joseph Wright's English Dialect Dictionary, EDD Online. At present, Markus is voluntarily working within a new project supported by the Austrian Science Fund on a revision of EDD Online and a complementation by its Supplement. The new version 3.0 will come out in 2018.

MANFRED MARKUS is a Full Professor Emeritus of English linguistics and mediaeval English literature at the University of Innsbruck. He has over a hundred publications on his record. With a background in English and American literature, he has, for the last thirty years, focussed on contrastive linguistics, historical English, corpus linguistics and English dialectology. He has compiled several corpora, among these the Innsbruck Corpus of Middle English Prose and the Innsbruck Letter Corpus 1386 to 1699. In 2016, he launched a digitised version (2.0) of Joseph Wright's English Dialect Dictionary, EDD Online. At present, Markus is voluntarily working within a new project supported by the Austrian Science Fund on a revision of EDD Online and a complementation by its Supplement. The new version 3.0 will come out in 2018.