INTRODUCTION

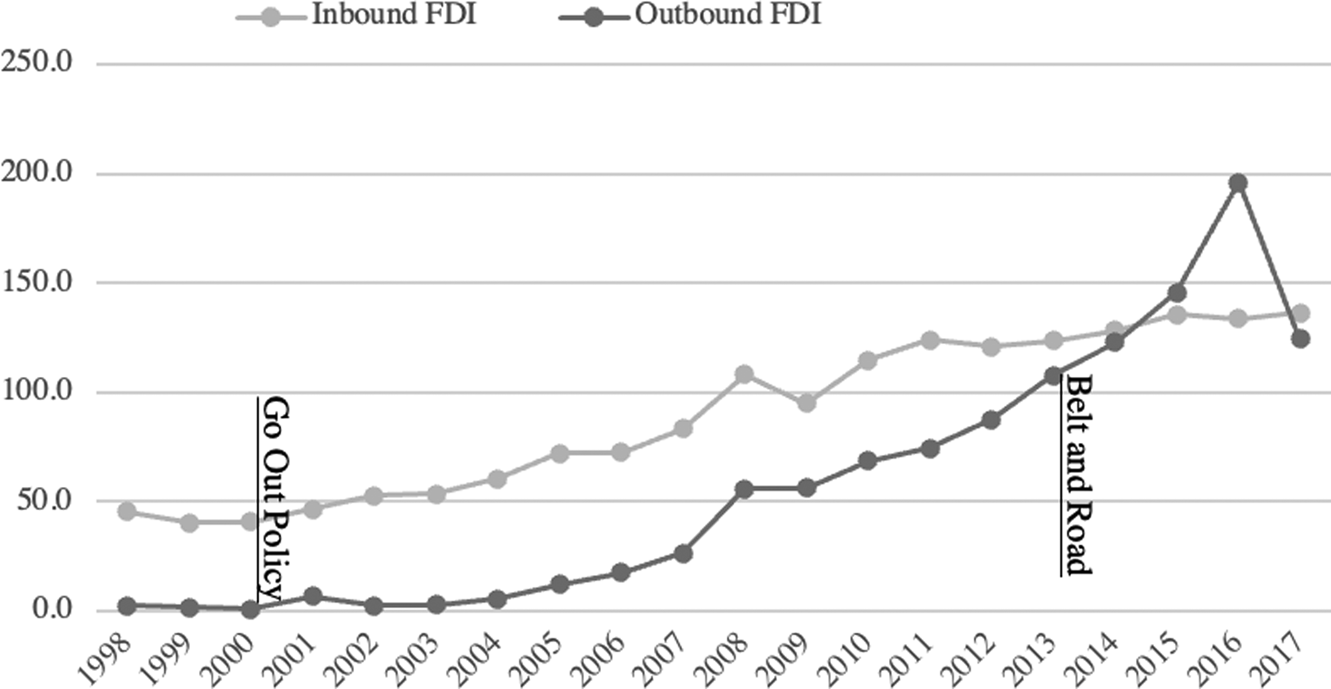

Once one of the largest importers of foreign capital among emerging economies (Prasad and Wei Reference Prasad, Wei and Calomiris2007), China's outbound investment has risen significantly over the last two decades (Figure 1). By 2014 China had become a net capital exporter in terms of direct investment (Veysel Reference Veysel2018).

FIGURE 1 China's Inward and Outward Investments (1998–2017)

Data From: Authors’ computation based on UNCTAD FDI statistics.

China is also now the world's largest development financier: outstanding loans by China's Export and Import Bank and China Development Bank exceeded $500 billion in 2018, more than all Western-dominated development banks’ lending combined (Chin and Gallagher Reference Chin and Gallagher2019). The launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, in particular, marked a new chapter in the global expansion of Chinese investment and lending. More ambitious than the Go Out Strategy of the early 2000s, the BRI features an unprecedented level of investment and financing commitment by China (Jiang and Shi Reference Jiang and Shi2018; Ye Reference Ye2020).

Many regard China's rapidly expanding global economic footprint, epitomized by the BRI, as driven by the Chinese government: First, the government sets overarching policy agendas to direct and mobilize China's capital outflow. The Go Out strategy emphasized energy security, expanding export markets, and diversifying China's excess foreign reserves. With its emphasis on infrastructure, the BRI stands to control important transport arteries and accomplish broad-based foreign policy goals. These objectives call into question the ultimate motivation of China's investment and lending: Is it economic or geopolitical?

The Chinese government intervenes in capital outflow through the ownership of globalizing enterprises and manipulation of financial levers. Although private enterprises are increasingly important actors in China's overseas’ investment, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which are by design both commercial entities and bearers of policy objectives, still account for nearly 50 percent of China's overseas investment flow (MOFCOM 2018). Furthermore, the financing of Chinese investment and lending comes in significant proportions from China's policy banks, largely state-owned commercial banks, and, increasingly, investment funds with ties to China's sovereign wealth funds or SOEs. Even if the investors are ostensibly private in terms of their ownership structure, their incentives and autonomy remain questionable when a state entity bankrolls their projects in part.

Owing in part to the state-directed nature of these capital flows, Chinese investment and lending generate widespread concerns among the recipients, despite China's repeated claims of “win–win cooperation.” The critiques range from “debt entrapment” in the BRI countries (Brahma Reference Brahma2017; Parker and Chefitz Reference Parker and Chefitz2018; Tillerson Reference Tillerson2018) to the harmful environmental and labor practices by Chinese firms and the loss of national sovereignty to China's economic statecraft (Norris Reference Norris2016; Lai Reference Lai2018).

At the heart of these concerns are two central questions: First, when the state leads economic actors, to what extent are their investment decisions driven by commercial considerations, and to what extent do they implement the political agenda of the state? Second, can state-led economic activities win public support among recipient economies, or are they bound to meet resistance and backlash, given the widespread concern that Chinese capital is ultimately directed by the state to accomplish China's strategic objectives?

The existing literature on China's engagement with the international economy offers limited answers to these questions. On the first question, the literature on state-controlled capitalism offers three conceptions of the state separately: 1) the state as a highly cohesive and strategic actor (Bremmer Reference Bremmer2017); 2) the state as a composite of industrial bureaucracies (Huang Reference Huang2008), and 3) the state as a composite of state-owned commercial entities (Naughton and Tsai Reference Naughton and Tsai2015). These different conceptions pay limited attention to the domestic institutions that shape the complex interplay between the leadership, central and local bureaucracies, financial sector, and firms, both public and private. As such, our understanding remains incomplete with respect to the economic and political dynamics driving China's capital outflow. On the second question, a burgeoning literature presents mixed findings on the impact and public reception of Chinese investment and lending on host countries. However, most of these studies are descriptive and do not address why Chinese investment and lending, directed and controlled heavily by the state, might generate positive or negative reactions.

This special issue sheds light on these two central questions and elucidates a more nuanced model for understanding China's economic globalization. This model has two key features: First, in the state system driving China's globalization, there is significant fragmentation of functions and thereby incentives among actors. Different Chinese state actors play differentiated roles in outbound investment and lending. The leadership, whose key function includes objective-setting and mobilization, employs a geopolitical rhetoric as a call to arms among the bureaucracy and economic actors. Economic actors, while responding to this call, follow predominantly commercial considerations in making investment decisions. The second feature of the model is that it is reactive. Domestic drivers and external feedback interact and mutually influence the patterns of China's capital outflow. Domestic institutions contribute to some of the adverse effects and negative perception among recipients. The backlash among recipients, in turn, provides feedback and leads to domestic policy adjustment, though the effects of recent policy adjustments remain to be seen.

In the first article, Min Ye outlines these two features of the model in detail. To illustrate the fragmentation of the political economic system driving China's BRI, Ye utilizes a tri-block structure, consisting of the leadership, bureaucracy, and economic actors, to conceptualize the Chinese state. This structure results in the coexistence of both Beijing's strategic logic and the predominantly economic interests followed by commercial actors during policy implementation. The strategic rhetoric adopted by Beijing, in combination with China's expanding economic footprint, generate political backlash and criticism of China among the recipients, forcing the Chinese bureaucracy to adjust BRI guidelines in Beijing. However, Ye predicts that, in this tri-block system, bureaucratic adjustment can only translate into substantive changes in the behaviors of commercial actors if it changes the commercial incentives facing Chinese investors at home and abroad.

The next two articles then illustrate this tri-block system at work through two cases. The second article, by Bo Kong and Kevin Gallagher, investigates the globalization of China's coal-power industry. Focusing on the nexus of bureaucracy and industries, they find that Chinese coal companies exploited conditions at home and abroad opportunistically, leading to a concentration of China's overseas energy financing in coal-powered plants. The third article, by Haitao Yin, Yunyi Hu, and Xu Tian, uncovers the implementation of one's BRI's key policy objectives, alleviating industrial overcapacity, at the local level. They find that China's localities face contradictory mandates from Beijing: environmental targets and economic growth. The localities increased exports of pollution-intensive goods to BRI countries while keeping the production of the goods and employment local. Together with Kong and Gallagher's article, the authors show that bureaucratic and economic actors have made investment and financing decisions that ultimately serve their own priorities.

In both cases, while actors make decisions in their own interests, their actions generate sometimes unintended consequences at home and abroad. In Kong and Gallagher's case, the coal-powered plants left environmental risks for the recipients and an obstacle for the world to address climate change. In Yin and colleague's case, China's localities have kept pollutants and environmental costs at home, defeating emission control targets from the central environmental agencies. These outcomes suggest that the actors’ actions are more in line with their narrow economic interests than Beijing's overarching geopolitical or environmental strategies.

While these two articles illustrate the tri-block system at work in China, the next two articles in this issue focus on investigating the impact and perceptions of Chinese investment and lending in the recipient countries, which in turn provide feedback for the tri-block system. The fourth article, by Weiyi Shi and Brigitte Seim, evaluates the “reputation deficit” associated with Chinese investment in Zambia, a developing country. Utilizing an original household survey, official statistics, and evidence from stakeholder interviews, they find that Chinese firms, compared to their Western counterparts, do not perform worse in contributing to local employment or in upholding labor or environmental standards. Thanks to the government's financial backstopping, Chinese firms in fact provide a more stable source of capital and employment against global economic downturns. However, their reputation suffers from a lack of localized corporate practices. The final article, by Audrye Wong, probes the question of why China's economic statecraft in a developed democracy, Australia, has had little success and has now spiraled into a full blown crisis in bilateral relations. She explains how non-transparent means adopted by Chinese capital to coopt public voices and influence Australia's foreign policy generate public and political backlash. In the recent diplomatic crisis, Beijing's use of coercive economic tactics undermined the buffering effects of economic interdependence and made China's inducements less attractive, escalating the backlash.

In sum, this special issue aims to enhance our collective understanding of the two central questions surrounding China's capital export under the auspice of the BRI and beyond: Can state-directed investment also follow a market rationale? And to what extent can Chinese capital, directed by the state in service of China's strategic objectives, win public support among the recipients? Our answers to these questions are nuanced. With regard to the first question, we show that with a fragmented tri-block system there is no cohesive and strategic state in China that “controls” capital decisions and movements, in spite of the existence of state-directed strategies like the Go Out policy and BRI. The connection is neither direct nor automatic between the state's policy objectives and economic actors’ behavior (Shi Reference Shi2015); overarching objectives and self-interested economic activities and bureaucratic behaviors co-exist. This co-existence can lead to unintended consequences, where policy objectives from the top are often distorted by actors’ self-interest in implementation. These consequences not only are reflected in Chinese firms’ excessive risk-taking when making decisions about investment (Shi Reference Shi2015), but also translate into departure from the central government's original policy goals such as reducing excess industrial capacity through the BRI (see Yin et al. in this issue).

With regard to the second question, we find that, although Chinese investment and financing have elicited backlash among recipients, the negative perception may not be as widespread as believed in certain localities, and where backlash is present or even intense not all of it can be blamed on the state-directed nature of China's economic expansion. The devils are in the details of on-the-ground implementation. The lack of corporate localization among Chinese firms in Zambia is not an inherent element of a state-led model. Recipients of Chinese capital are ultimately reacting to how economic actors from China behave and what impact they exert, and not to the abstract construct of a strategic Chinese state. China's failed economic statecraft in Australia is not a result of the injection of Chinese capital per se, but of how some of this capital has been injected through non-transparent means to coopt public voices and political actors and threatens the integrity of democratic processes in Australia.

Meanwhile, the external backlash against China has not gone unnoticed by policymakers in Beijing and has facilitated policy adjustments. The working of a feedback loop—explicated by Ye in the first article—was evident for the BRI from 2017 to 2019. At the first BRI Summit in 2017, China promoted BRI as “the Project of the Century,” pledging substantial state investment and infrastructure financing. By mid-2019, the second BRI Summit emphasized “sustainable” and “high-quality” development, reflecting an awareness of and efforts by the Chinese leadership to address China's “reputation deficit” among recipient economies.

As we prepared this special issue, none of us anticipated the eruption of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. The pandemic puts the course of globalization under further strain. Will the BRI survive? Will the Chinese government increase or decrease efforts to expand its global economic footprint? Insights developed in this issue remain relevant for anticipating answers to these questions: In a fragmented system, actors pursue self-interest. Vested interests including the bureaucracy, SOEs, and local governments have developed surrounding the BRI and have persisted during and after the pandemic (Ye Reference Ye2021). In addition to its strategic objectives, the BRI is also a personal legacy project for Xi Jinping (Jiang and Shi Reference Jiang and Shi2018), who could remain in office beyond 2023, since the new constitution has removed leader term limits. The BRI is likely to continue for those reasons alone, not to mention that China is likely to emerge from the pandemic an even more pivotal economic power. Much like the global financial crisis (GFC) a decade ago, the COVID-19 crisis is poised to be another turning point that will shift China's terms of engagement with the rest of the world. However, unlike the GFC, when the world looked to China as an emerging engine of growth and promising leader, China now faces greater challenges in addressing a global backlash against its particular brand of state capitalism and assertive foreign policies. Whether it is in a developing country like Zambia or a developed democracy like Australia, China still has a long way to establish a positive reputation for its economic presence.

STATE CONTROL OVER CAPITAL OUTFLOW: EVOLUTION AND DEBATES

The scholarship on Chinese capitalism tends to conceive the state either as a strategic actor, an aggregation of economic bureaucracies, or as a mix of SOEs and banks. What remains underexplored are the domestic institutions that connect these different parts of the state and how they collectively shape China's capital globalization in the BRI and beyond. In this section, we first provide a brief overview of China's state-led model for economic globalization and its evolution. We then summarize diverse views on this model in the literature. Following that we explain our approach, which considers the roles of the political leadership, industrial bureaucracies, and economic actors in driving China's capital outflow holistically. We then outline how our approach may revise some of the commonly held views of how Chinese outbound capital affects recipient countries.

EVOLUTION OF STATE CONTROL

In the last four decades, China's economic globalization, development planning, and political stability have hinged upon the state control of financial institutions and capital movements (Naughton Reference Naughton2017). The state control over capital has two prongs in China: Firstly, the state exercises capital control overflows across national borders. Secondly, the state owns powerful banks and companies that drive the course of development and globalization. Such a state control system has been the root cause of suspicion about Chinese capital abroad. However, this control system has also undergone significant changes in the past two decades and has become so pluralized that various stakeholders’ preferences often diverge.

Starting in the 1980s, while China aggressively pursued inbound foreign investment and helped create global production networks on the mainland (Ye Reference Ye2014), it was restrictive toward outbound investment due to capital scarcity. Even when the country's capital account balance shifted toward surplus in the early 2000s, and Chinese companies had a strong momentum to invest abroad, the state maintained a variety of restrictions over China's capital outflows.

However, the 2000s saw piecemeal yet significant deregulation of outward financial flows. The economic actors—state banks, SOEs, private companies, and local governments—made increasingly significant investments abroad without changing statutory capital controls (Ye Reference Ye2014). In line with the investors’ interests, state agencies such as the Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Commerce, and State Assets Supervision and Administration Council conducted “fragmented liberalization,” allowing some localities greater opportunity for outbound investment, or companies in specific sectors, such as electronics and natural resources, to access more foreign exchange to invest abroad. The Go Out policy facilitated this fragmented liberalization. As the leadership urged Chinese companies to increase domestic and international markets and access internal and external resources, SOEs and local governments had more flexibility and justification for launching overseas projects.

The combination of capital control, Go Out policy, and fragmented liberalization in the 2000s present a complex picture for China's state-led economic globalization. In particular, when a state company invests abroad in the name of the leadership's strategy while evading capital restriction to seek profits at the same time, should we view such investments as driven by the state's political goals or the investors’ commercial interests? Norris (Reference Norris2016) and Downs (2016) analyzed Chinese national oil companies’ outbound acquisitions in this period and found that the companies’ business interests were predominant. At times, their overseas projects even undermined the leadership's geopolitical goals in the recipients (for example, in Sudan).

Similarly in more recent times, the BRI has been promoted as a centerpiece of Chinese foreign policy, aiming to achieve the Chinese nation's overall rise on the world stage. However, Ye's article in this issue shows that bureaucracies and industries have mainly utilized BRI to serve their priority to expand influence or business abroad, rapidly increasing outbound investment and financing after its launch. Concerns about financial instability peaked in Beijing in 2017, and the government re-imposed restrictions on capital outflows, bringing down the volume of outbound investment sharply (AEI 2018). The Chinese state does exercise control over capital flow, but economic actors reacting rapidly to market conditions often outpace the government's attempts to maintain control.

China's SOEs and banks are important workhorses driving both the Go Out strategy and now the BRI. Over the decades, however, waves of SOE reform have given these entities significantly more commercial autonomy while maintaining their policy functions. As such, China's SOEs have assumed essential roles as commercial actors responsible for the safety of and return on state assets (Kroeber Reference Kroeber2015). However, in implementing strategic objectives of the leadership, SOEs tend to leverage the strategy to promote their own interests and seek economic rents (Shi Reference Shi2015). On the whole, SOEs have shown considerable flexibility in deciding whether and how to implement the BRI (Ye Reference Ye2020).

In sum, China's state-led model for capital export comprises control over foreign exchange (i.e., capital control), banks, and firms. As China becomes increasingly integrated with the global economy and as new venues and instruments burgeoned in recent years, state control over capital movement has become more porous. As SOEs and state-run banks are given greater commercial autonomy and become more marketized, ownership over banks and firms also do not guarantee faithful implementation of the strategic objectives of the state. The ambitious and vague strategies announced by political leaders, like the BRI, have in fact given economic actors expanded opportunities to pursue their commercial incentives.

DIVERSE VIEWS ON STATE CAPITALISM

China's state-capitalist system is like the proverbial elephant: various observers of different parts would arrive at competing characterizations of the system. Furthermore, the system has constantly evolved in recent years, with increasing opacity to outside observers. Focusing on SOEs and the leadership's power over them, Barry Naughton and Kellee Tsai (Reference Naughton and Tsai2015) underscore the state's political penetration into state capital as a defining character of Chinese capitalism. Naughton (Reference Naughton, Fingar and Oi2020) conceptualizes the power of the leadership imposing on state and non-state companies as a form of “grand steerage”—not total control, but broadly determining investment decisions in the economy. Pearson, Rithmire, and Tsai (Reference Pearson, Rithmire and Tsai2020) have recently coined the term “Party-State Capitalism” to describe a more coercive and controlled system than conventional descriptions of “state capitalism.”

Expanding such characterizations abroad, Ian Bremmer (Reference Bremmer2017) has viewed China's state-dominated capitalism as strategically driven, and has concluded that it has “beaten” the American system. Jude Blanchette (Reference Blanchette2021) calls Chinese capitalism the “CCP, Inc.,” possessing “an unrivaled ability” to deliver the complete value package to foreign countries and afford China immense global force.

Different from such an emphasis on the state's political and strategic control, other scholars underscore commercial tendencies and the market rationale in China's state capitalism. For example, Christopher McNally (Reference McNally2012) has offered a complex picture of SOEs and argued that Chinese capital simultaneously embodies top-down policy priority and bottom-up entrepreneurship. Yuen Yuen Ang (Reference Ang2016) illuminates how interactions between top-down and bottom-up mechanisms have contributed to market efficiency and rapid economic growth in China during the reform era. In Nicholas Lardy's formula of “Market, not Mao,” market mechanisms are seen as the driver of China's economic success (Lardy Reference Lardy2014). Although Lardy (Reference Lardy2019) recognizes China's reform has retreated under the current leadership, he is insistent that China's growth and future success will continue to be based on market mechanism and private businesses’ vitality. While the state exercises considerable control and intervention, Chinese capital has mostly followed market rationales and pursued commercial interests (Zheng and Huang Reference Zheng and Huang2018). For Ye (Reference Ye2020), localized implementation of the Western Development Program and China Goes Out reveals market rationales in dictating local governments and companies’ actual investment decisions.

On China's policy banks, scholarly views are similarly divided. Some are worried that the Chinese banks are “malevolent state policy tools” that would not adhere to the high standards of competitive bidding and social and environmental standards preferred by Western-led multilateral banks (Parker, Chassany, and Dyer Reference Parker, Chassany and Dyer2015). Furthermore, the state-owned banks subsidize and support Chinese firms expanding into the global market, which then compete with US and European firms for leadership in cutting-edge technologies (Blanchette Reference Blanchette2021). Other scholars, working on China's financing in developing countries, are less alarmed. Deborah Brautigam and Kevin Gallagher (Reference Brautigam and Gallagher2014) found that Chinese banks have generally operated on “market” terms, similar to other foreign banks operating in similar contexts. Chinese bank leaders such as Jin Liqun repeatedly pledged to be “clean and lean” in making Chinese lending abroad (Saldinger Reference Saldinger2017).

Dichotomous assessments of SOEs and state banks cannot capture the dualist nature of these entities: they are both bearers of the state's policy objectives and commercial actors; and this combination can produce unintended consequences. With the recent surge in the party and state-centered view on Chinese capital (Gertz and Evers Reference Gertz and Evers2020; Blanchette Reference Blanchette2021; Schuman Reference Schuman2021), observers risk magnifying the strategic intention associated with Chinese capital and neglecting the market incentives ultimately driving such capital flow. Overemphasis on state's strategic intent and capacity for control is counterproductive: First, this perspective steers scholarly debates toward the dynamics of interstate competition and political control, while leaving the complex market mechanisms driving China's capital outflow underexplored. Paradoxically, while China's global economic spread is incentivized by the state, this spread—ultimately enabled by market mechanisms—also has an inherent tendency to outpace the government's capacity for control (Shi Reference Shi2015). Second, this state-centric perspective overlooks the considerable, systemic risks generated by ultimately profit-driven economic activities and actors from China. Just as a state-controlled process does not necessarily impart negative impacts on the recipients—a point we illustrate later in this issue—porous and incomplete state control also does not mean the impacts will be inherently benign. In fact, profit-driven investment and financing activities can have a more immediate negative impact on both the recipients (Ang Reference Ang2019) and China (Lampton, Ho, and Kuik Reference Lampton, Ho and Kuik2020).

In this special issue, we unpack the Chinese state and explain the complex interaction between “the state” and “capital” in shaping China's outward investment and financing. Our articles provide a framework that accounts for actors with heterogeneous preferences to govern China's capital outflow and the consequences abroad. Outlining the domestic institutions underlying the Chinese state, we establish that fragmented motives and actors shape the BRI and the globalization of Chinese capital more generally. Operating under such a system, no matter how influential the core leaders are and how strategic industrial planners appear to be at the top, the bottom-level implementers and specific investment behaviors largely conform to a market rationale and commercial calculus.

DOMESTIC INSTITUTIONS SHAPING CHINA'S CAPITAL OUTFLOW

The primary agenda in this special issue is to investigate domestic institutions inside China's state-directed capitalism and explain how they fragment the state's control and regulation of capital. We focus on three levels of analysis of domestic institutions and address: 1) Why the authoritarian party-state has only a partial influence on the behavior of capital, 2) how the bureaucracy-industry complex shapes China's development financing internally and internationally, and 3) to what extent commercially motivated actors determine BRI implementation patterns on the ground and the actual effects on the economy and environment.

THE STATE SYSTEM

China's political economy and the interaction between the ruling CCP and the state are complex. Even more complicated are the questions of how and how much the state system influences Chinese capitalist behavior abroad (Zheng and Huang Reference Zheng and Huang2018). Many observers attribute the country's external activities to the CCP's strategic and political motivations (Gill Reference Gill2020; Blanchett Reference Blanchette2021). More nuanced studies, however, have emphasized that economic actors’ priorities and preferences shape their investment decisions abroad (Downs 2016; Ye Reference Ye2019).

Reconciling the controversy, the first article in this issue, by Min Ye, formulates a general framework for describing the Chinese state. It unpacks the Chinese state into three blocks—the leadership, bureaucracy, and economic arms—and observes that, on major policies, this system is fragmented across the three blocks. The leadership holds political power over the bureaucracy and economic actors, but leaders lack the capacity or incentive to control the day to day functionality of the bureaucracy and economic actors. Bureaucracies thus perform functional roles in implementing state policies, and the capitalists seek to maximize profits while carrying out the state's policy priorities. Due to this fragmentation, capitalists have long exercised a certain degree of autonomy and flexibility in reinterpreting and deviating from national policies set in Beijing.

The tri-block state system results in multi-staged policy processes in China. Ye's article finds that in BRI and other global strategies, the top leadership has intervened the most in the policy's launch phase. Yet, before the leadership can intervene, the need for policy responses is urgent, while bureaucracies are often too divided to act. After the strategy's launch, bureaucracies and industries insert preexisting practices and proposals to (re-)define the BRI's content. Subsequently, during implementation, SOEs and subnational actors have flexibly interpreted and conducted the BRI according to their interests, inline or out of line with Beijing's political rhetoric and industrial policies.

As the BRI emerges as the signature foreign policy in China, it has also met vocal criticism and resistance abroad. External concerns are particularly intense regarding environmental and social disruption, financial risks, and compromising the recipient's sovereignty. Consequently, state-financed BRI has largely failed to expand China's diplomatic space or soft power abroad. Such political backlash has been transmitted back to Beijing in a feedback loop; in response, the bureaucracy has adopted joint statements with multilateral organizations and cooperated with other investor countries to address such concerns. However, for Beijing's adjustment to work, economic actors’ incentives will need to be shifted, too.

Ye's study of the Chinese state and BRI adds insight to our understanding of the state system and how it fragments the control over the outgoing capital. The tri-block state formula, comprising leadership, bureaucracy, and state capital, integrates the earlier literature on central–local fragmentation (Heilmann and Melton Reference Heilmann and Melton2013; Ang Reference Ang2016; Chen Reference Chen2018) and the divergence between the state and state capital (Shi Reference Shi2015, Li and Zeng Reference Li and Zeng2019). The BRI cycle in Ye's article reveals how various state actors play divergent parts in different stages of the strategy: strategic rhetoric by the leadership to mobilize other state actors, industrial capacity cooperation pursued by the bureaucracy, and commercial tendencies dominating local governments and companies. The state structure and the policy process provide a general framework for theory-building and empirical discussion in other articles in the special issue, focusing on the bureaucracy-industry complex, local government and business nexus, and perceptions and realities of Chinese outbound capital, respectively.

THE BUREAUCRACY-INDUSTRY COMPLEX

In the tri-block system, central ministries and agencies are essential players in China, and their primary motivations are associated with industrial interests in the country. Like bureaucracies in high-growth Japan (Johnston Reference Johnson1982), South Korea (Amsden Reference Amsden1989), and Taiwan (Wade Reference Wade1990), China's agencies also undertook industrial planning, incorporating industrial interests while guiding national industrial restructuring. Recently, scholars have increased their study of China's development planning and how plans were implemented and contributed to China's growth (Kennedy and Johnson Reference Kennedy and Johnson2016; Heilmann and Melton Reference Heilmann and Melton2013; Naughton Reference Naughton, Fingar and Oi2020).

In this issue, Kong and Gallagher's article provides a detailed account of agencies and companies in the energy sector and explains how they have affected China's capital outflow. The analysis reveals behavioral patterns at the bureaucratic and industrial levels. Focusing on the process starting in 2008 when China had a large financial surplus and mounting pressure to “green” its energy industry, the article reveals how the pull and push factors propelled China to become one of the most prominent financiers of coal-fired power plants in the world.

The causal story involves dynamic interactions between the bureaucracy, domestic industries, and external market forces. Firstly, Chinese agencies such as NDRC sought to upgrade industrial technology and green China's coal-power sector. Then, other emerging economies, which had rising dependence on coal and declining financing from the West, were compelled to turn to China for funding after the West pulled out. Finally, coordinating the “push” and “pull” factors, China's policy banks promoted overseas coal-powered plant financing to increase external demand and help Chinese companies export, thereby reducing domestic coal consumption and fulfilling the country's green targets.

This process demonstrates a combination of state and market drivers in the context of shifting domestic and external conditions. Kong and Gallagher found that China's economic bureaucracies, when facing pressures to promote green energy, did not just shift coal production abroad. They used state financing and foreign market expansion to promote cleaner and more advanced coal plants abroad, thus creating the demand for “greener” technology in China's coal sector. But, simultaneously, China's coal companies conveniently used the policy direction to expand business in the coal sector, rather than diversifying into cleaner energy sources such as renewables. Globalization as a domestic adjustment strategy may have worked for the bureaucracy and coal companies facing overcapacity and new environmental regulations, but it is a mixed blessing for China's and the worlds’ environmental outcomes, as coal-powered plants have now been sustained and expanded further with the industry's global reach.

Following Ye's article, Kong and Gallagher demonstrate that state financing patterns reflect state agencies’ responsiveness to both market demands and strategic industrial planning. More generally, the article demonstrates that development priorities and industrial agencies inside China have bearings on China's outbound investment and external financing. However, the kind of projects that are realized and their external effects also reflect the demands and institutional contexts of the recipients of Chinese capital. When non-Chinese capital withdraws and leaves investment gaps in the recipients, China's financing has more space to grow; when the institutional environment is lax in the receiving market, China's projects are more likely to present social and environmental risks for recipients.

LOCAL STATE-BUSINESS CONNECTION

In the tri-block state system, the third block—local governments and enterprises—are the most numerous and direct implementers of the BRI. What is the landscape of interests at the local level? How different are they from national policy? Do local decisions follow the top-down, overarching rhetoric or parochial calculations specific to the localities? Answers to these questions shed light on the actual effects of the BRI in China and abroad.

In the third article of this issue, Haitao Yin, Yunyi Hu, and Xu Tian examine the local governments and businesses in pollution-intensive industries and the ways in which they have implemented the top-down BRI strategy. Their framework starts with contradictory regulations that local governments face in China and demonstrates that the BRI allows them to choose suitable and locally driven options. The article counters the pollution haven hypothesis (PHH), which predicts that the BRI would incentivize Chinese polluting enterprises to relocate factories abroad and increase environmental threats in the hosts. Instead, it finds that 1) local governments in China have motivations to keep factories and employment local and 2) relocation to foreign hosts are unfeasible or costly for the companies. As a result, polluting producers and localities have utilized the BRI to export their finished products abroad while keeping production (and pollution) at home.

The article analyzes trade statistics between China and BRI countries to arrive at the following findings: China's imports in pollution-intensive industries have not grown faster from BRI than from non-BRI countries, suggesting that the strategy did not boost outward investment for offshoring production in these industries. The trade data demonstrate that exports of finished pollution-intensive products (such as leather, chemicals, and metal) increased significantly from China to the BRI countries from 2014 to 2016.

Yin, Hu, and Tian calculate the economic and environmental effects of the BRI. On the economic side, the trend of price indices suggests that increased exports of pollution-intensive products from China to BRI countries have helped to expand and stabilize the market demand facing Chinese companies, keeping their production afloat. In terms of impact on the environment, the article calculates pollutants and their amounts generated in China as a result of increased exports to BRI countries. Localized and commercially driven implementation of the BRI may have helped address China's industrial overcapacity issue in the short run, but it has worsened China's environmental challenges.

REACTIONS TO CHINESE CAPITAL FROM RECIPIENT COUNTRIES

The first three articles in this special issue focus on domestic institutions and how they shape China's economic globalization, but they also note the importance of the external environment in shaping China's polices and patterns of capital flow. Reactions from the external environment are inputs into the policy feedback loop described in Ye's article. External “pull” factors outlined in Kong and Gallagher's article and the restrictions on relocation discussed by Yin, Hu, and Tian both highlight the role of the external environment in shaping outcomes in China's capital flow. The final two articles of this issue extend this line of inquiry and shift focus to investigate reactions to the influx of Chinese capital in recipient economies. Through the cases of a developing economy and a developed democracy, they evaluate empirical evidence for Chinese capital's effects on the recipients and probe the causes of the global backlash against China's economic presence.

Recall the two central questions we present at the beginning that drive the intellectual agenda of this special issue. The first question, examined in the first three articles, probes the relationship between the Chinese state's strategic agenda and the actions of economic actors. The second question shifts the focus to the reaction from recipient economies. In particular, when Chinese capital is directed from the top to pursue China's strategic objectives, to what extent can it win public and political support among recipients? What explains the backlash against China's economic presence among host economies?

Our answers to these questions are nuanced. In the case of Zambia, Weiyi Shi and Brigitte Seim find that the public generally express high levels of support for Chinese investment, but Chinese firms do suffer from a “reputation deficit” compared to other multinational firms operating in the country. This deficit is more pronounced in Audrye Wong's account of Australia, where China's economic statecraft has elicited a strong political backlash. Neither article, however, finds a direct connection between the backlash and the state-directed nature of China's model for economic globalization. In Zambia, Shi and Seim trace this reputation deficit to the limited localization of Chinese firms’ corporate practices. In Australia, Wong attributes the backlash to China's lack of transparency in using political donations and academic funding to influence the public discourse. However, Beijing's recent use of coercive economic tactics against Australia, which threatens to reduce the economic interdependence between the two countries, has intensified this backlash.

In the existing literature, concerns about the impact of Chinese investment and lending on host economies fall into three main areas: dubious developmental benefits, debt entrapment, and China's practice of economic statecraft compromising the sovereignty of recipient economies. However, we know little as to: 1) to what extent these perceived impacts are corroborated by empirical evidence, 2) whether these perceived impacts have contributed to the public discontent and backlash facing Chinese actors on the ground, and 3) to what extent such backlash is a direct result of China's state-directed model for globalizing its economic footprint. In the following sections, we review the main lines of arguments and debates in the current literature about the impacts of China's economic presence on host countries and explain how the articles in this issue challenge or add nuance to some of the prevailing conclusions in the literature.

DEVELOPMENTAL BENEFITS

Analysts have debated the extent to which Chinese investment and lending can generate developmental benefits for recipient countries regarding local employment, labor conditions, and environmental protection. Empirical evidence has been mixed. While some studies show that Chinese investment generates jobs (Wang, Mao, and Gou Reference Wang, Mao and Gou2018; Kubny and Voss Reference Kubny and Voss2010), others note that the employment created tends to be lower in quality (Huang and Ren Reference Huang and Peiqiang2013). Chinese overseas companies have poorer labor conditions. For example, Baah and Jauch (Reference Baah and Jauch2009) find that Chinese companies operating in several African countries tend to pay lower wages than local and other foreign firms and often break regulations on contracts. Others are more positive and view Chinese investment and lending as a “boom” to capital-strapped nations (Gallagher Reference Gallagher2016). Chinese investment has improved local residents’ access to basic infrastructure (Schiere and Rugamba Reference Schiere and Rugamba2011; Urban et al. Reference Urban, Nordensvärd, Khatri and Wang2012) and contributed to economic development (Li Reference Li2010; Bräutigam Reference Bräutigam, Alden, Large and de Oliveira2008; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zadek, Yu, Halle, Velasquez, Zhang and Wang2016). For example, in Mauritius, Chinese manufacturers served as “flying geese” and sped up local industrialization (Bräutigam Reference Bräutigam, Alden, Large and de Oliveira2008). China's aid practices in Africa are no worse than those of Japan and the West (Brautigam Reference Deborah2009); Chinese development financing also seems to follow environmental standards equally well as other development banks (Chin and Gallagher Reference Chin and Gallagher2019).

More importantly, the current literature says little about whether there is a link between the actual development impacts of Chinese investment and financing and the level of public support for Chinese projects. Corroborating this link, or the lack thereof, is important: if economic benefits for the populace do not translate into public support, China's capital export becomes “lose–lose” in the long run for the recipients and for China. Shi and Seim highlight the need to distinguish real impacts from the public's expressed level of support. They show through an original household survey of formal sector employees in Zambia's Copper Belt that, while Chinese investors’ treatment of labor is not significantly worse than that of western firms in actuality, the public have a more negative perception of Chinese firms. Further, they identify the source of this “reputation deficit”: a lack of localization and reluctance to engage the local media. That is, the source of this reputation deficit is not a shortfall in developmental benefits, but of Chinese companies’ specific corporate practices on the ground.

A lack of localization is neither a direct result of China's state-directed model for economic globalization or a phenomenon unique to China. In terms of impact that is specific to a state-run model, Shi and Seim illustrate a counterintuitive mechanism in which Chinese capital, with the state's financial backing, can offer developmental benefits to recipient countries where investment from Western economies cannot. Government-backed financing allows Chinese investors to be more resistant to the ups and downs of business cycles and serve as a more stable source of capital for distressed economies. They demonstrate this by comparing Chinese SOEs’ reaction to the global financial crisis with other multinational mining firms in Zambia's copper sector. However, the translation of such benefits to public support is hampered in the case of Chinese companies by a lack of localized corporate practices.

DEBT ENTRAPMENT

The second area of concern is that Chinese lending, particularly loans associated with the BRI, entangle recipient countries in so-called debt traps. These debt burdens can threaten recipients’ growth trajectory and political sovereignty (Hurley, Morris, and Portelance Reference Hurley, Morris and Portelance2018; Ameyaw-Brobbey Reference Ameyaw-Brobbey2018; Were Reference Were2018). It is feared that, unable to service debts to China, recipients will have to yield control over their resources, strategic infrastructure, and policy autonomy to China. An often-cited example is China's takeover of Sri Lanka's Hambantota port in a debt-for-equity swap deal for 99 years after the Sri Lanka government failed to meet a scheduled debt repayment (Abi-Habib Reference Abi-Habib2018).

While the jury is still out on the impact and sustainability of China's overseas lending, the implicit assumption of the “debt trap” hypothesis is that Chinese lending, at its core, is an instrument of China's geopolitical maneuvering. According to this argument, China intends to use its status as a creditor for political leverage and geopolitical gain over-indebted nations and has developed its lending strategies accordingly. A more extreme “debt trap” argument even claims that China deliberately pushed borrowing governments into unsustainable debt to security and resources from the recipient countries (Pence Reference Pence2018).

Kong and Gallagher's article in this issue provides evidence that the driver of China's overseas lending is economic and not political. The main aim of financing overseas coal power was to shift the burden of China's industrial upgrading abroad and to eliminate excess capacity in the domestic coal power sector. To the extent that such lending creates “entrapment,” it would be more appropriately regarded as the negative externality of China's flawed industrial policy than a strategic design to yield geopolitical influence.

Ye also counters the “debt trap” argument, by analyzing policy process and project-level information. Specifically, regarding China's controversial loans to Sri Lanka and Pakistan, it was commercial fallout on the borrowing governments, not Beijing's deliberate “entrapment,” that resulted in the debt-servicing difficulties. And in both cases, China actively renegotiated the loans, at the host government's suggestion (in Sri Lanka's case) and involving the IMF in debt resettlement (in Pakistan). In the feedback and adjustment phase, Ye also finds that Beijing has started to address the debt concern and make policies that would help reduce the financial risks in future BRI projects.

INFLUENCE OF CHINA'S ECONOMIC STATECRAFT

The third concern for recipients is that China's economic statecraft—using financial means to achieve geopolitical objectives—would compromise the recipients’ sovereignty and harm their interests. In the international relations literature, economic statecraft has focused mainly on punitive sanctions (Baldwin Reference Baldwin1971, Reference Baldwin1985; Pape Reference Pape1997; Drezner Reference Drezner1999). Most studies of China's economic statecraft have similarly focused on the potential coercive effects of trade dependence on China (Fuchs and Klann Reference Fuchs and Klann2013; Davis, Fuchs, and Johnson Reference Davis, Fuchs and Johnson2014). Increased dependence, whether in terms of trade, investment, or lending, increases China's political leverage and ability to coerce economic partners into taking certain foreign policy positions, should China choose to do so.

However, another aspect of economic statecraft, arguably describing China's strategy more aptly, is positive inducements, where financial incentives are offered to alter a target state (Nincic Reference Nincic2011; Norris Reference Norris2016). We have little understanding as to what determines the success or failure of such inducements. For example, although Beijing has provided extensive investment and aid to Southeast Asia countries, this capital has not prevented tensions from boiling over into sovereignty disputes in the South China Sea. Some would consider the BRI to be one giant program of economic statecraft. However, it is also meeting resistance in developing and developed economies alike, and, arguably, especially in countries where China has made the most infrastructure investments like Pakistan and Malaysia.

Examining Australia's case, Wong demonstrates the limitations of China's current approach to economic statecraft. When China offers economic inducements in non-transparent ways that undermine political norms and processes, it elicits public backlash. This outcome increases the reputational costs for globalized Chinese capital, already subject to negative perceptions due to China's authoritarian capitalism. In contrast, cultivating domestic stakeholders in recipient countries can help increase support for cooperative relations. As the membership of BRI continues to expand and increasingly includes developed economies and mature democracies, Wong highlights the limits to China's current approach in coopting their support. Beijing's recent use of economic coercion against Canbrella has further undercut the effect of “positive inducement” and results in ever-increasing political backlash in Australia and beyond.

From standpoint of the recipient, Wong also highlights the importance of the quality of domestic institutions in the host economy in mediating the potential threats presented by China's political interventions. In a way, public backlash arose against China's nontransparent practices because Australia is a mature, well governed democracy. Thus, whether China's attempts at economic statecraft compromises the recipients’ interests is likely to be highly conditional on the quality of governance in the host country.

In sum, the articles in this issue collectively advance our understanding of the impact of Chinese capital on recipient countries and the ways recipients react to this capital influx. They provide much needed empirical evidence that qualifies some of the prevailing concerns about Chinese investment and lending: whether investment and lending directed by an authoritarian state generate concrete benefits for the recipients and under what conditions China's economic statecraft can be counterproductive. They paint a highly nuanced picture of China's investment and lending consequences that helps to distinguish reality from perception and attempted statecraft from actual influence. Ultimately, as we trace the mechanisms driving the global backlash against Chinese capital, it would appear that none of the proximate causes we find so far—lack of localization in Zambia or non-transparent funding in Australia—are inherent features of a state-run model. However, when such proximate causes are combined with a strategic rhetoric from Beijing, broad-based political and public backlash can occur, as Wong illustrates in the case of Australia.

CONCLUSIONS

In the last decade, China has become a rapidly rising investor economy globally, and its financial power is likely to grow after the Covid-19 pandemic. It is also the principal investor country with distinct domestic politics and economic institutions that baffle observers in developed and developing countries alike. Internally, the Chinese system rests on a “cohesive” image at the top level but with fragmented motives and actors in the bureaucracy and local governments. Externally, perceptions and reputations often capture one side of the system, particularly the leadership's geopolitical control and strategic motivations. By unpacking the Chinese state, this issue provides a more nuanced and integrated analysis of China's capital globalization. It sets up a general framework to account for different state motives in China and a feedback loop connecting internal and external politics in shaping Chinese capital. Consistent with Chinese outward capital's complexity and significance, the issue integrates domestic political analysis with expertise in energy, environment, and foreign policy. In the coming years, China's outward capital is likely to have impacts and risks beyond the conventional domains of comparative and international political economy.

This special issue takes an essential step in addressing China's perceived threat to global development and the environment. A critical insight is that, although strategic objectives have driven China's expanding economic footprint, China's economic actors, even state-owned enterprises and policy banks, are not compliant state agents. China's challenge to the global economic system is first and foremost commercial: Chinese firms, backed by state financing, can foray into markets deemed too costly and risky for Western firms. China's global economic spread can also become over-leveraged, as firms and banks make investment and lending decisions without fully internalizing the cost of capital and generate systemic risks for the recipient and the global economy. Though commercial in nature, these challenges can also become politicized, eliciting backlash from the BRI countries and creating conflicts with advanced economies like the United States. In this regard, China still has a long way to go to manage the impact of its capital export effectively, where commercial competition can easily convert to geopolitical jousting despite China's proclaimed intentions.

Finally, as the world faces challenges and uncertainties due to the Covid-19 pandemic, findings from this volume shed light on what China might do in the post-COVID world and potential changes in China's outward investment in the future. On the one hand, the articles on domestic drivers have demonstrated broad-based commercial motives underlying China's outbound investment and various actors such as state agencies, the industry, and local business interests implementing the BRI. Hence, even as the pandemic has worsened the external environment facing China and as Xi is pushing to enhance the strength of “internal circulation” in China's economy, the country's commitment to and interest in globalization are likely to continue. On the other hand, the volume shows that China's outbound capital is meeting backlash abroad. In the post-COVID world, Chinese policymakers will likely continue to adjust their policy rhetoric and priorities to reflect these reactions and assure recipients that cooperation is “win–win.” However, it remains uncertain whether such adjustments will be considered credible and whether the Chinese state can prescribe timely policy adjustments as varied as the situations on the ground.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank anonymous reviewers and Stephen Haggard for helpful comments during various stages of the draft.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare none.