Introduction

Rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT) (Ellis, Reference Ellis1994, Reference Ellis2003) is a prominent cognitive behavioural approach to psychotherapy, which distinguishes itself from other cognitive behavioural approaches by proposing that psychological illbeing is caused by irrational beliefs. A core aspect of REBT is the ABC model, which suggests that in the face of an adverse or stressful event (A), our emotional and behavioural responses (C) are caused not by A alone, but by our beliefs (B) about A. These beliefs can be either irrational or rational, whereby irrational beliefs are unrealistic, excessive, inflexible and illogical, and rational beliefs are realistic, coherent, flexible and logical. Irrational beliefs can be subsumed into four categories: demandingness, awfulizing, frustration intolerance and global evaluation, whilst rational beliefs can be subsumed into the four categories of: preferences, anti-awfulizing, frustration tolerance and unconditional acceptance (DiGiuseppe et al., Reference DiGiuseppe, Doyle, Dryden and Backx2014). The four irrational beliefs have been arrived at through several iterations of REBT theory. When REBT was conceived by Albert Ellis in the 1950s, 11 irrational beliefs were proposed, but have since been condensed into four core irrational beliefs. In addition, several irrational belief themes have also been proposed, often referred to as ‘contents’ such as achievement, approval, comfort, justice and control (Magoaşe et al., Reference Magoaşe, Stefan and David2013). Aside from the recategorization of irrational beliefs, perhaps more pertinent questions should be asked about irrational beliefs, such as: should we consider irrational beliefs to be general (non-specific), or situation/context-specific? Should we assess irrational beliefs in relation to individuals’ experiences (activating events) in a context-specific manner, or in a general (trait) manner, detached from contextual matters?

Ellis (Reference Ellis1994) pointed out that situation-specific or context-specific beliefs are stronger indicators of emotional and behavioural consequences than general or non-specific ones. Indeed, DiLorenzo et al. (Reference DiLorenzo, David and Montgomery2011) found that specific rational and irrational beliefs were stronger predictors of functional and dysfunctional distress than general irrational beliefs. In a recent meta-analysis (Visla et al., Reference Visla, Fluckiger, Grosse Holtforth and David2016), it was found that irrational beliefs are more strongly related to distress insituations in which a stressor is personally relevant, actually present, and real. Some other research investigated irrational beliefs within specific situations (e.g. using social vignettes; Lohr et al., Reference Lohr, Brandt and Bonge1977) such as in relation to scholarly exams (e.g. Attitude and Beliefs Scale-II; DiGiuseppe et al., Reference DiGiuseppe, Leaf, Exner and Robin1988, DiGiuseppe et al., Reference DiGiuseppe, Leaf, Gorman and Robin2017). In experience and agression of anger (Martin and Dahlen, Reference Martin and Dahlen2004) it is found that certain types of (not general) irrational beliefs were activated by specific situations or emotions. Gitlin (Reference Gitlin1988) suggests that reliable associations should be obtained between various subscale patterns and specific emotional and behavioural problems in order for therapists to reliably predict the troublesome belief patterns of clients based on their symptoms, and viceversa. Therefore, the targeting of context-specific irrational beliefs for intervention is necessary and will strengthen REBT’s practical application.

Given the importance of context-specific irrational beliefs measurement, the goal of the current study is to develop and test a new context-specific psychometric for irrational beliefs, drawing on self-determination theory (SDT; Deci and Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan1985). That is, in the current paper a new psychometric that assesses irrational beliefs concerning the three basic psychological needs (BPNs) formulated within SDT is developed and validity tested. By measuring irrational beliefs in this way, it is possible to understand how irrational beliefs about these important needs might influence psychological health outcomes, rather than examining general irrational beliefs and BPNs separately. In addition, this psychometric is developed for use with adolescents, in whom irrational beliefs, and the BPNs, have been shown to be important factors in determining psychological wellbeing. By measuring irrational beliefs within the context of the three BPNs, specifically in adolescents and in contexts relevant to this population group, we may gain a greater understanding of, and be able to offer effective solutions to, the psychological illbeing of adolescents.

Since the late 1990s there has been an increase in mental illness among children and adolescents (Costello et al., Reference Costello, Mustillo, Keller, Angold, Levin, Petrila and Hennessy2004). With the development of a positive psychology paradigm, problem-oriented psychotherapy schools, such as REBT, have applied their methods to develop prevention programmes. Researchers have successfully applied REBT programmes with school children identified as ‘at-risk’ for depressive symptoms and conduct, poor educational success, and problematic peer relationship issues (Banks and Zionts, Reference Banks and Zionts2009; Jaycox et al., Reference Jaycox, Reivich, Gillham and Seligman1994). However, whilst REBT has been considered a problem-oriented therapy (Corey, Reference Corey2013) driven by cognitive restructuring (Corsini and Wedding, Reference Corsini and Wedding2011), the promotion of rational beliefs in REBT supports the positive pursuit of long-term wellbeing and goal attainment, rather than short-term hedonic happiness (Ellis and Dryden, Reference Ellis and Dryden1997; Szentagotai and David, Reference Szentagotai and David2013). As such, Ellis has been labelled an unsung hero of positive psychology (Bernard et al., Reference Bernard, Froh, Digiuseppe, Joyce and Dryden2010). Much research has shown that SDT and positive psychology programmes can yield advantageous outcomes in adolescents (e.g. Niemic and Ryan, Reference Niemic and Ryan2009; Núñez and León, Reference Núñez and León2015). Indeed, prevention-based positive psychology interventions have been conducted successfully in elementary and secondary schools in the UK (Eades, Reference Eades2005), Australia (Noble and McGrath, Reference Noble and McGrath2008; Williams, Reference Williams2011) and Portugal (Marques et al., Reference Marques, Lopez and Pais-Ribeiro2011). In one study, 352 9th-grade students participated in a positive psychology prevention programme, with results showing enhancements in student pleasure and commitment in school, and social skills such as empathy, collaboration and self-control (Seligman et al., Reference Seligman, Ernst, Gillham, Reivich and Linkins2009).

As programmes based on SDT and REBT may separately provide beneficial outcomes for adolescent psychological health, one might reasonably expect that a combination of SDT and REBT would provide a more economical and effective model for the prevention and treatment of mental illness. Consequently, we suggest that a combination of REBT and SDT could create a framework for adolescent psychological wellbeing by addressing adolescents’ BPNs via REBT through the reduction of irrational beliefs, and the promotion of rational beliefs.

The combination of SDT and REBT is grounded in conceptual similarities (Turner, Reference Turner2016) and past research (e.g. Turner and Davis, Reference Turner and Davis2018). SDT distinguishes between intrinsically motivated self-determined actions and extrinsically motivated controlled actions, positing that the fulfilment of three basic needs – autonomy, competence and relatedness – is necessary for true motivation, psychological development, authenticity, strength, self-congruence and prosperity (Ryan and Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2001). SDT proposes that if youngsters can feel autonomy, competence and belongingness in school, they will feel additional intrinsic enthusiasm to study, will more deeply value and connect school-relevant assignments, and will experience more prominent psychological wellbeing (La Guardia and Ryan, Reference La Guardia and Ryan2002). As Ryan and Deci (Reference Ryan and Deci2001) indicated, intrinsic motivation may help the person facilitate self-awareness, self-direction and self-regulation. REBT has also recognised the importance of intrinsic motivation in the pursuit of self-actualisation. Albert Ellis (Reference Ellis2001; Ellis and Dryden, Reference Ellis and Dryden1997) explains that ‘fully functioning persons tend to enjoy work and sports as ends or pleasures in themselves and not merely as means towards ends (e.g., working for money or playing sports to achieve good health). As REBT puts it, commitment to people, things, and ideas, mainly because people want to be absorbed and committed, is one of the main aspects of emotional health and happiness’ (p. 191). The notion that intrinsically, rather than extrinsically, regulated motivation is more beneficial for wellbeing is echoed in what Ellis writes here. Indeed, recent research (Davis and Turner, Reference Davis and Turner2019; Turner and Davis, Reference Turner and Davis2018) has demonstrated that REBT can be successfully used to promote greater self-determined motivation, intimating a positive relationship between irrational beliefs and less self-determined (more controlling) motivation.

In SDT, the satisfaction of BPNs is a key driver of greater self-determined motivation, but whilst basic needs are recognised as important, REBT deters rigid and extreme beliefs regarding the basic needs. Albert Ellis (Reference Ellis2001) contested the notion that to be mentally healthy one must be in control and competent. An implication of ‘needing’ to be competent and autonomous implies that those who are less competent and have less volition over their pursuits are less likely to be able to be happy. Individuals who dogmatically demand to be competent and autonomous, and who deem their happiness and self-worth as contingent on these needs being fulfilled, are less likely to unconditionally accept themselves, and thus are less likely to remain psychologically healthy. Unconditional self-acceptance (USA; Ellis, Reference Ellis2001) is a cornerstone of REBT, and is negatively related to depression and anxiety (Chamberlain and Haaga, Reference Chamberlain and Haaga2001). Also, low USA can lead to self-blame and self-criticism (Hill et al., Reference Hill, Hall, Appleton and Kozub2008) and self-centeredness (Neff, Reference Neff2003). Rather than hinging mental health on the satisfaction of basic psychological needs such as autonomy, competence and relatedness, Ellis (Reference Ellis2003) maintained a more elegant philosophy: ‘I exist; I appear to have a good possibility of being happy if I continue to exist; therefore I deserve to exist (or think it would be better to preserve my existence) and to live happily’ (p. 229). Ultimately, self-worth is not contingent on need fulfilment.

So, whilst the three BPNs are demonstrably important for mental health, rigidly demanding that these needs are fulfilled, and making oneʼs self-worth dependent on such need fulfilment, could undermine mental health. Take autonomy, for example, which in SDT is considered to be intrinsic to self-governance (Ryan and Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2006). It is clear that some problems may arise when adolescents confer irrational beliefs onto their autonomy needs. For example, an adolescent could make themselves anxious about various pursuits by adopting the irrational autonomy belief that ‘I must always decide and do whatever I want, otherwise things are terrible/I can’t stand it/it makes me totally worthless person/my parents are useless’. The irrational belief of demandingness for autonomy (‘I must’), awfulizing (‘it is awful’), low frustration tolerance (‘I can’t stand it’), and deprecation/condemnation beliefs (‘I am worthless or they are worthless’) about not being autonomous may trigger some problematic incidents between the child and his or her parents, teachers and friends. Irrational beliefs about autonomy may lead adolescents to maladaptive and unhealthy emotions and behaviours, such as anxiety, anger and aggression, or depression and withdrawal. On the other hand, rationally wanting autonomy, evaluating a lack of autonomy non-extremely, and accepting oneself in the event of barriers to autonomy fulfilment are more in keeping with rational beliefs and subsequent adaptive and healthy emotions and behaviours.

The need for competence reflects the feeling of being effective in achieving oneʼs own desired outcomes and practising oneʼs capacities (Ntoumanis et al., Reference Ntoumanis, Thogersen-Ntoumani, Deci, Ryan, Duda and Williams2012). For instance, adolescents adopt and internalize a goal if they understand it and have relevant skills to accomplish it (Ryan and Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2008). SDT postulates that both autonomy and perceived competence are necessary conditions for the enhancement and maintenance of intrinsic motivation (Deci et al., Reference Deci, Koestner and Ryan1999). By demanding competence, and attaching self-worth to competence fulfilment, the risk posed to wellbeing is not that one is not competent per se, but rather that this perceived lack of competence is evaluated in an extreme and rigid way, and that oneʼs self-worth is in some way diminished as a result.

Relatedness in SDT refers to feeling understood and cared for by others, the sense of being close to others (Ryan and Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2001), having satisfactory relationships and social support from significant people (Deci et al., Reference Deci, Eghrari, Patrick and Leone1994; Grolnick et al., Reference Grolnick, Benjet, Kurowski and Apostoleris1997), and getting support from peers (adolescents; Field et al., Reference Field, Hoffman and Posch1997). This notion can clearly be integrated to REBTʼs concept of unconditional other acceptance (UOA; Ellis, Reference Ellis2003), which is one of the major concepts in REBT (DiGiuseppe et al., Reference DiGiuseppe, Robin and Dryden1990). Irrational beliefs about relatedness may be related to being approved of, and being rejected, by others. For example, ‘I must have close and sincere relationships with others, otherwise I am a worthless/unlovable person’. The child may become depressed because being rejected is deemed ‘awful’ or ‘intolerable’, and is ironically less able to form strong relationships with others due these extremely negative self-perceptions. The rational equivalent ‘I wish I have close and sincere relationships with others, and if I don’t, I am still a worthwhile/lovable person’ still expresses a desire for nutriment fulfilment, but also importantly incorporates a flexible belief as well as unconditional self-acceptance.

The three BPNs may not be attainable by an individual alone. People are viewed as dynamic creatures, following up on their inward and outer conditions based on internal structures that are repeatedly elaborated and refined with enhanced understanding (Deci and Ryan, Reference Deci and Ryan1985). Connell and Wellborn (Reference Connell and Wellborn1991) explained in their ‘context, self and action model’ that people need others and the available environmental conditions (e.g. norms, culture, economic and social conditions), as well as patterns of action through cognition, behaviour and emotions, to satisfy their psychological needs (Connell and Wellborn, Reference Connell and Wellborn1991). People may face difficulties and frustrations along the way to achieving these needs. For instance, in a romantic relationship, a person depends partly on another to satisfy their relatedness needs. A stressful event may create a problem between the partners, thus reducing perceptions of relatedness. If they also harbour some irrational beliefs about relatedness, then this will further hinder the relationship in part by having deleterious effects on psychological wellbeing. Similarly, for competence and autonomy needs, others (e.g. teachers, coaches, managers, supervisors) can have an impact on our perceptions of competence and autonomy, and can create a climate for needs fulfilment or needs thwarting. When others thwart our need’s fulfilment, irrational beliefs about needs satisfaction can only serve to worsen the deleterious effects of not having our needs fulfilled.

In sum, whilst the three BPNs should be ideally striven for in the interest of psychological health, holding irrational beliefs about these needs can undermine efforts to fulfil these needs and worsen the illbeing effects of unfulfilled or thwarted needs. In order to understand the effects of irrational beliefs concerning the three BPNs, first we must develop accurate ways of measuring irrational beliefs concerning them. That is, measuring irrational beliefs about autonomy, competence and relatedness needs may provide opportunities to prevent emotional and behavioural problems in the academic, social and family life of adolescents. Therefore, in the current study an irrational beliefs measure is developed that assesses irrational beliefs within the context of the three BPNs proposed in SDT: the Rational Emotive Self Determination Scale for Adolescents (RESD-A; see Supplemental Material). Preliminary evidence (Türkmen, Reference Türkmen2018) suggests that there is a positive correlation between scores on the RESD-A and child depression. Parental support on basic psychological needs was found to be moderately correlated with scores on the RESD-A. In another preliminary study, higher scores on the RESD-A were related to greater perfectionism and exam anxiety in adolescents (Demirci, Reference Demirci2018).

The RESD-A integrates REBT and SDT constructs to offer a more nuanced and contextually specific assessment of irrational beliefs by assessing beliefs about the three BPNs. The extant research literature does not contain a similar psychometric to the RESD-A, but some child and adolescent measures of irrational beliefs have been developed as non-context-specific measures. For example, the Child and Adolescent Scale of Irrationality (CASI; Bernard and Cronan, Reference Bernard and Cronan1999) measures irrational beliefs in children and adolescents, using items referring to general beliefs such as ‘I cannot stand having to behave well and follow rules’ and ‘It’s really awful to have lots of homework to do’. Another scale, the Childrenʼs Survey of Rational Beliefs (Knaus, Reference Knaus1974) for use with 7- to 10-year-olds and 10- to 13-year-olds, measures general beliefs rather than specific beliefs. The CASI was afterward restructured and enhanced by the authors (Bernard and Cronan, Reference Bernard and Cronan1999) to address the four core irrational beliefs across the contents of comfort, achievement and control (DiGiuseppe et al., Reference DiGiuseppe, Doyle, Dryden and Backx2014). However, the study of Terjesen et al. (Reference Terjesen, Kassay and Anderson2017) on the psychometric properties of the Child and Adolescents Scale of Irrationality failed to yield interpretable factors based on the theory of REBT and the reliability of the subscales was low. Therefore, whilst child and adolescent irrational beliefs have been developed, to our knowledge no psychometric has been developed that addresses the three BPNs.

The current paper proposes, and validity tests a new psychometric, the RESD-A, to integrate two prominent theories and offer a new perspective on adolescent behaviour. To achieve this, we conducted four studies. In Study 1, we conduct item development and exploratory factor analyses (EFA) takes place, Study 2 contains confirmatory factor analyses, and in Study 3 we investigate the initial estimates of internal consistency for the RESD-A and examine re-test reliability (Artiran, Reference Artiran2015). In Study 4, we test the construct validity of the RESD-A (Artiran, Reference Artiran2015).

Study 1: scale development and factor structure

Method

The aim of Study 1 was to develop items in accordance with REBT and SDT, and to conduct EFA to assess the factor structure of the RESD-A.

Participants and procedure

Participants were 120 adolescents (female = 51; male = 69) selected conveniently from high schools in Istanbul. All participants took part on a voluntary basis. The sample mean age was 15.20 (SD = 1.90; range 12–18). Data were gathered during class hours by special permission from the admission department of the school. The participants were furnished with the purpose of the research and informed consent was obtained prior to data collection. The psychometric instruments were completed in an empty classroom and lasted no longer than 45 minutes.

Item generation and response format

First, we developed the pool of potential items both coherent with REBT’s ABC model and basic psychological needs theory proposed within SDT, as well as suitable for 12- to 17-year olds. Items were generated by reviewing extant irrational beliefs questionnaires (e.g. Attitude and Beliefs Scale-2; Bernard, Reference Bernard1998; DiGiuseppe et al., Reference DiGiuseppe, Leaf, Exner and Robin1988, Reference DiGiuseppe, Leaf, Gorman and Robin2017) to understand their strengths (e.g. clarity of wording and expression of irrational beliefs), and weaknesses (e.g. measuring behaviours or emotions rather than beliefs such as in the Irrational Beliefs Test; Jones, Reference Jones1968), and the language appropriate for adolescents (e.g. the Child and Adolescent Scale of Irrationality; Bernard and Cronan, Reference Bernard and Cronan1999). Items were developed by the research team which included REBT-trained psychotherapists and psychologist. An expert panel of judges (researcher, REBT supervisor, two psychologists with a doctorate degree, and a school counsellor) were employed to examine content validity of the items in relation to REBT and SDT. In addition, the face validity (Nevo, Reference Nevo1985) of the items was assessed by 15 high school students, and 15 parents. After explaining the purpose of the test, these reviewers were asked whether items were suitable and worded correctly or not, by using a form with three choices: yes, no, no idea. Reviewers indicated that the items had high face validity, and all items were clear and suitably aligned with theory.

To conform with REBT, the stem and instructions for completing the measure followed the REBT ABC model (Ellis, Reference Ellis1994; Ellis and Dryden, Reference Ellis and Dryden1997). That is, participants were asked to respond to a set of three activating events (A; scenarios) related to autonomy, competence and relatedness in order to reveal their irrational beliefs (B) of demandingness, awfulizing, frustration intolerance and global evaluation (Ellis, Reference Ellis2001, Reference Ellis2003) about these activating events. There are three activating events for each of three BPNs. A total of 51 items was developed (see Table 1) with 18 items measuring autonomy irrational beliefs (AIB), 18 items measuring relatedness irrational beliefs (RIB), and 15 items measuring competence irrational beliefs (CIB). Items were measured on a Likert-scale between 1 (strongly disagree) and 5 (strongly agree) in line with prominent irrational beliefs measures (e.g. Turner et al., Reference Turner, Allen, Slater, Barker, Woodcock, Harwood and McFadyen2018). Lower scores indicate lower irrational beliefs, and high scores indicate greater irrational beliefs. The RESD-A has been developed based on a continuum model, rather than a binary model. According to theoretical assumptions, irrational beliefs and rational beliefs are not bipolar constructs (Bernard, Reference Bernard1998). Participants may not naturally make the discrimination between irrational beliefs and rational beliefs (Magoaşe et al., Reference Magoaşe, Stefan and David2013). Therefore, the RESD-A assumes that higher scores represent greater risks of psychological distress in line with past research (Visla et al., Reference Visla, Fluckiger, Grosse Holtforth and David2016) and viceversa.

Table 1. The development of a measure of RESD-A

* Each item measures one activating event in the RESD-A scale.

When developing the items for the RESD-A, items for CIB on other depreciation were not appropriate for the measure construction. To explain, activating events for CIB are about oneʼs own ability, success and skills, not the competence of others (e.g. activation event number 1: ‘My teacher asked me a question during a lecture and I couldn’t provide an answer’). In contrast, considering autonomy and relatedness, one can irrationally believe that: others are worthless due to not having these needs fulfilled. For example, one of the AIB items includes the activating event ‘What you are doing in your free time has been managed by your parents, and they decide what you are going to do in those times’. The questionnaire continues with a question: ‘Imagine the situation as realistically as possible and tell us what you would think or believe about this type of situation’:

(1) I definitely shouldn’t be restricted.

(2) Being restricted is catastrophic/awful.

(3) I cannot stand it when I am restricted.

(4) In such situations, I believe that I am not worthy.

(5) In such situations, I believe that life is not worthy.

(6) In such situations, I believe that who is restricting me is unworthy.

The CIB and RIB items followed a similar structure but referred to activating events relevant to competence (CIB) and relatedness (RIB).

Results

Factor structure of the RESD-A

The results of the EFA analysis indicated a three-factor model. A principal-axis factor analysis with oblique rotation method (Direct Oblimin; Delta = 0) was performed on the 51 items (the table of EFA can is available on request from the first author). The amount of total variance accounted for by the three factors was 45.20%. EFA determines the possible factor structure of a set of variables without imposing a preconceived structure on the result (Child, Reference Child1990). However, we actually targeted the measurement of three structures: AIB, CIB and RIB. Results indicated that the three-factor structure strongly fitted the theoretical expectations of the three BPNs (autonomy, competence and relatedness) as proposed within SDT. Factor loadings are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Second-order exploratory factor analysis

RESD-A’s AIB subscores ranged from 18 to 90, with a mean of 52.04 (SD = 16.36). RIB subscores ranged from 18 to 90, with a mean of 49.33 and an SD of 14.81. RESD-A’s CIB subscores ranged from 15 to 80, with a mean of 40.88 and an SD of 12.76. RESD-A’s total score ranged from 51 to 255, with a mean of 142.25 and an SD of 31.27 (minimum 66, maximum 245). Subscores of RESD-A and total scores of RESD-A are normally distributed based on skewness and kurtosis values (–0.8 to 0.8 for skewness and –3.0 to 3.0 for kurtosis (George and Mallery, Reference George and Mallery2010; Tabachnick and Fidell, Reference Tabachnick and Fidell2013). Cronbach’s alpha values of the subscales were found to be .78 for AIB, .84 for CIB, and .82 for RIB.

Study 2: confirmatory factor analysis of RESD-A

For confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) the maximum likelihood estimation method was used with LISREL 8.5 software (Jöreskog and Sörbom, Reference Jöreskog and Sörbom1993). We used t-indices of goodness-of-fit statistics: root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). Values of 0.90 and above for the GFI and CFI indicate acceptable model fit. Values of SRMR and RMSEA between –0.08 and 0.08 indicate a good model (Hu and Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1999; Kline, Reference Kline2005; Şimşek, Reference Şimşek2007).

Method

Participants

The research sample used for the CFA analysis consisted of 202 high school students (female = 92; male = 110). The sample had a mean age of 15.9 (SD = 1.51; range 13–18). Participants were conveniently selected (on a voluntary basis) from two high schools in Istanbul. Each administration took place in a quiet room and lasted between 45 and 55 minutes. All participants consented to take part.

Procedure

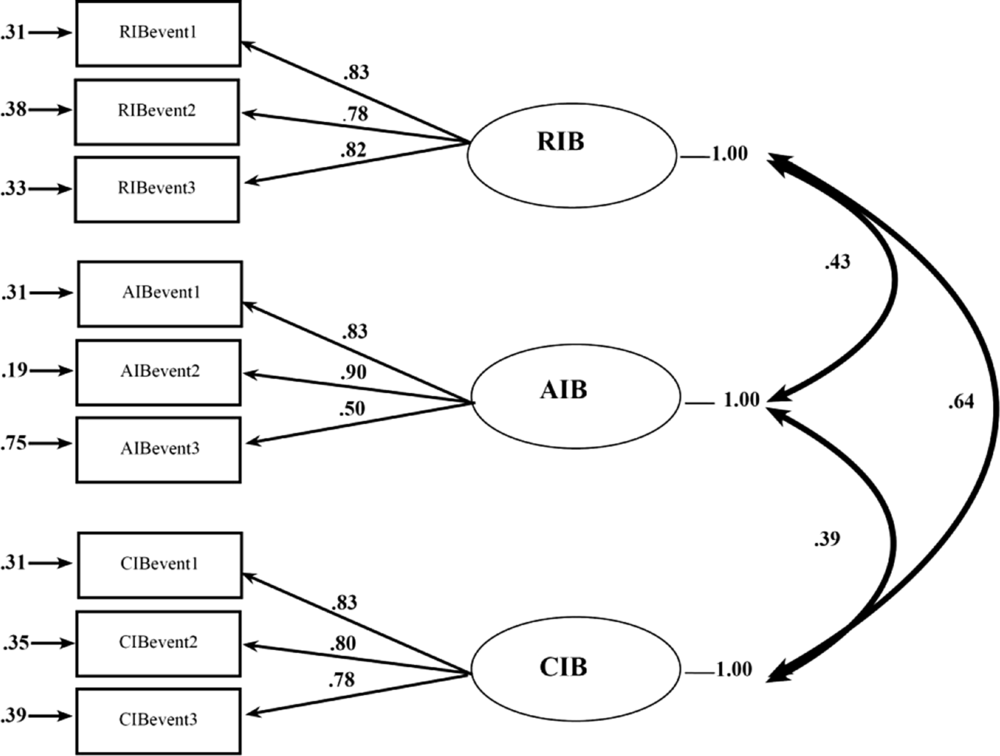

According to the structure of the RESD-A, we conducted explanatory second-order factor analysis that revealed three factors. Using structural equation modelling (SEM), CFA provides the degree of any relationship between observed variables and their latent constructs (Jöreskog and Sörbom, Reference Jöreskog and Sörbom1993). After factor loadings had been determined, CFA was performed on the RESD-A using SEM, using maximum likelihood estimation. Testing the model, goodness-of-fit statistics was taken as fitness criteria such as chi-square statistic (Byrne, Reference Byrne1998). To be clear, the proposed model in Fig. 1 was analysed by maximum likelihood estimation method.

Figure 1. CFA results for three-factor model. RIBevent, activating event on relatedness irrational beliefs; AIBevent, activating event on autonomy irrational beliefs; CIBevent, activating event on competence irrational beliefs.

Results

On 51 items, Bartlettʼs test indicated a chi-square of 781.998 (d.f. = 36, p < .01), further attesting to the factorability (Newcomb, Reference Newcomb1994) of the data set. CFA results are represented in Table 3, and the best goodness-of-fit statistics were produced for the three-factor model, indicating an almost perfect fit for the data. In addition, correlation coefficients for the three RESD-A latent variables were r = .43 (p < .05) between RIB and AIB, r = .64 (p < .05) between RIB and CIB, and r = .39 (p < .05) between AIB and CIB (see Fig. 1). Kline (Reference Kline1998) states that hypotheses are confirmed if the estimated parameter for each path of the structural model is significant, that is, with the t-value >1.96 for p < .05. According to t-test results, all parameters were significant with the t-value of over 1.96 value (p < .05). In the 3-factor model, t-test values in all parameters ranged from 7.07 to 13.43 and were statistically significant.

Table 3. Fit indices for the RESD-A derived from confirmatory factor analyses

N = 202; χ2, chi-square; d.f., degrees of freedom; CFI, comparative fit index; GFI, goodness-of-fit index; AGFI, adjusted goodness-of-fit index; SRMR, standardized root mean square residual; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; Model AIC, the Akaike information criterion (AIC); ECVI, expected cross validation index.

Study 3: test–re-test reliability

Method

Participants and procedures

The sample for Study 3 was a convenience sample selected from high school students in Istanbul. All participants took part on a voluntary basis and provided consent. Sixty-two students (female = 27; male = 35) participated to assess the test–re-test reliability of the RESD-A. The sample had a mean age of 16.5 (SD = .49; range 16–17). The tests were administered by a certified psychologist. We conducted a test–retest reliability study across a 3-week interval, and used Pearson’s product–moment correlation coefficients to examine the associations between the subscales of the RESD-A at the two time points.

Results

The results (see Table 4) indicated moderate to high reliability: r = .85 for AIB (p < .01), r = .87 for CIB (p < .001) and r = .70 (p < .01) for RIB, and total score of RESD-A r = .82 (p < .001).

Table 4. Re-test reliablity for three factors

N = 62, p < .01.

Study 4: construct validity

Study 4 tested the construct validity of the RESD-A by investigating the correlations between the RESD-A and BPN satisfaction, functional, dysfunction and positive emotions, anger, distress, positive self, and anti-social behaviours.

Method

Participants and procedure

Data were collected from two different high schools in Istanbul (n = 158; female = 76; male = 82; mean age = 16.21 years, SD = 1.38; range = 13–18). All participants took part on a voluntary basis. The participants were informed about the aim and scope of the research and consented to take part. The instruments were completed in a class hour with special permission by school administration. Each administration lasted 45 minutes.

Instruments

The Basic Psychological Needs Satisfaction Scale (BPNS) – Relationships Domain

The BPNS in relationships (La Guardia et al., Reference La Guardia, Ryan, Couchman and Deci2000) is widely used in SDT research (Deci et al., Reference Deci, Ryan, Gagné, Leone, Usunov and Kornazheva2001) and consists of nine items assessing the three BPNs concerning relationships on a 5-point Likert-scale (La Guardia et al., Reference La Guardia, Ryan, Couchman and Deci2000).The BPNS in relationships allows the administrator to indicate the relationships in which the BPNs are being measured. In the current study, we had participants complete the scale about their parents. For example, for the item ‘When I am with XXXX I feel free as who I am’, we filled the XXXX part with ‘mother and father’. Kesici et al. (Reference Kesici, Üre, Bozgeyikli and Sünbül2003) translated the BPNS into Turkish language from English. They reported internal consistencies of α = .73 for autonomy, α = .61 for competency, and α = .73 for relatedness. Cronbachʼs alpha reliabilities in the current study were respectively α = .66, α = .63 and α = .63.

Reynolds Adolescent Adjustment Screening Inventory (RAASI)

The RAASI (Reynolds, Reference Reynolds2001) is a self-report measure with 32 items measuring significant adjustment problems for adolescents in the areas of Antisocial Behaviour, Anger Control, Emotional Distress, and Positive Self on a 5-point Likert-scale. For example, ‘I broke the rules in school’, ‘I drank some alcohol’, ‘I didn’t complete my homework’. In the Turkish adaption of the questionnaire, the internal consistency (α) was found to be .81. The Cronbach’s alpha for the current study was α =.88.

The Profile of Affective Distress (PAD)

The PAD (Opriş and Macavei, Reference Opriş and Macavei2005) was developed from McNair, Lorr and Droppleman’s (Reference McNair, Lorr and Droppleman1971) profile of mood states (POMS), but from an REBT perspective. The PAD consists of 39 items divided into three categories (12 items for functional emotions, 14 items for dysfunctional emotions, and 13 items for positive emotions). Using a 5-point Likert-scale participants indicated the extent to which they felt emotions such as worry, tenseness, happiness, cheeriness, and so on. Adaptation of the scale into Turkish had not been undertaken in past research. The Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities were found to be α = .77 in this study.

Results

Means and standard deviations of all study variables are shown in Table 5. The correlations between the BPNS variables and the RESD-A variables were all negative and statistically significant. The RESD-A subscale was positively correlated with RAASI subscales measures anti-social behaviour, anger control problems, emotional disturbance, and negatively correlated with positive self. For subscales of the PAD, the total score of RESD-A was negatively related to positive emotions, and positively related to both functional and dysfunctional negative emotions. The RESD-A total score was more strongly related to dysfunctional negative emotions than functional negative emotions. In the same direction as for the total RESD-A score, associations between RESD-A variables and functional, dysfunctional and positive emotions were all significant. Finally, the RESD-A subscales were significantly and negatively associated with the corresponding parental support subscales.

Table 5. Relationships of RESD-A, and subscales of AIB, CIB and RIB with BSN, RAASI and PAD variables

PARAUT, parental support of autonomy; PARRLT, parental support of relatedness; PARCOM, parental support of competence; FONK, functional emotions; DIS, dysfunctional emotions; POZ, positive emotions; ANTI, anti-social behaviours; ANGER, anger problems; DISTRES, emotional distress; POZTFSELF, positive self.

General discussion

The aim of the present paper is to develop a context-specific irrational beliefs scale for adolescents concerning the three BPNs as proposed in SDT. According to the results, the RESD-A has three components that measure the four core irrational beliefs (demandingness, awfulizing, frustration intolerance and global evaluation) about the three BPNs (autonomy, competence and relatedness): AIB, CIB and RIB. EFA results clearly identified a three-factor solution which was strongly supported by CFA. Although theoretical expectations suggest that the BPNs are three independent components, self-report scales of BPNs have been shown to be so highly correlated that it is hard to advocate their orthogonality (Şimşek, Reference Şimşek2013). Such a psychometric problem also resulted in the corruption of the original three-factor structure of the scales. For instance, Johnston and Finney (Reference Johnston and Finney2010) claimed that the BPNS is a two-factor scale (competence and autonomy), not a three-factor one. In relation to this, the RESD-A scale is consistent with SDTʼs expectations. Three BPNs were clearly identified in our studies and were shown to be orthogonal, most probably as a result of using scenarios concerning the three BPNs.

The psychometric properties of irrational beliefs measures have been criticized in the past. First of all, the definition of irrational beliefs presents some confusion in related literature (DiGiuseppe and Zee, Reference DiGiuseppe and Zee1986; Eschenroeder, Reference Eschenroeder1982). Indeed, some of the most commonly used irrational beliefs questionnaires contain items that measure emotions and behaviours rather than beliefs. Some early psychometrics such as the Irrational Beliefs Tests (IBT; Jones, Reference Jones1968) the Rational Behaviour Inventory (RBI; Shorkey and Whiteman, Reference Shorkey and Whiteman1977) and the Idea Inventory contain many items that do not measure cognitions (e.g. beliefs) but emotions and behaviours (Bridges and Harnish, Reference Bridges and Harnish2010). Early measures such as the RBI and the IBT (Jones, Reference Jones1968) have serious discriminant validity problems. It has been concluded that the IBT, in correlating more highly with an anxiety measure than with an irrationality measure, lacked discriminant validity (Smith et al., Reference Smith, Houston and Zurawski1983). The RESD-A, however, seems to overcome such problems and offers new constructs using REBT and SDT.

Indeed, specialized assessment of irrational beliefs has already been recommended. Psychometrics such as the Irrational Food Beliefs Scale (Osberg et al., Reference Osberg, Poland, Aguayo and MacDougall2008), the Gamblers’ Beliefs Questionnaire (Steenbergh et al., Reference Steenbergh, Meyers, May and Whelan2002), and the irrational Performance Beliefs Inventory (iPBI; Turner et al., Reference Turner, Allen, Slater, Barker, Woodcock, Harwood and McFadyen2018) all demonstrate excellent psychometric properties. As such, for the first time in the literature the RESD-A provides a good context-based scale that can be applied to measure irrational beliefs concerning autonomy, competence and relatedness needs in adolescents.

The correlation of the RESD-A subscales with BSN satisfaction, RAASI and PAD variables indicates that the RESD-A has a potentially close association with mental health. First, according to construct validity analysis, the RESD-A is significantly related to greater anti-social behaviour. Second, the relationships of RESD-A with functional (but negative) and dysfunctional emotions were positive as expected. Positive emotions and RESD-A subscales were also negatively correlated. Consequently, adolescents with higher levels of irrational beliefs about BPNs seem to be vulnerable to mental health complaints, while individuals lower in irrational beliefs about BPNs seem to be more able to effectively deal with activating events.

This paper not only tests the validity and reliability of RESD-A but also suggests a new integrated theoretical approach based on REBT and SDT. Specification of context seems to have been a good solution for construct validation for the integrated REBT and SDT constructs. Such a combined approach may work better than REBT or SDT alone in a therapeutic sense. For example, in addition to challenging irrational beliefs per se, adolescents may benefit from specific challenges to their irrational beliefs about BPNs. For instance, the main goal of therapy is to help the client to autonomously discover, define, instruct and carry on a process of change; yet SDT does not provide a complete treatment plan for clinical cases (Ryan and Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2008). When REBT is aligned with the three BPNs, we may be able to help clients satisfy their autonomy needs through non-absolutistic demands relating others or ourselves; our competence needs through unconditional self-acceptance; and our relatedness needs through unconditional other-acceptance. REBT uses many behavioural techniques to motivate clients to change, such as shame attacking, role-playing and behavioural rehearsal (Ellis and Bernard, Reference Ellis and Bernard2006), stemming from classic behavioural therapy (e.g. Skinner, Reference Skinner1988; Wolpe, Reference Wolpe1958). However, up until now research has not tested the integration of REBT with the motivational framework of SDT. Past research has indicated that irrational beliefs may be related to the motivation regulation types within SDT, chiefly introjected regulation (Turner, Reference Turner2016; Turner and Davis, Reference Turner and Davis2018), but the current study is the first to test an integrated model of irrational beliefs and BPNs. For a more detailed discussion about the integration of REBT and SDT, see Turner (Reference Turner, Bernard and Dryden2019).

According to Ryan and Deci (Reference Ryan and Deci2008) the client internalises responsibility for the process of change, otherwise long-term success may not be maintained. Introjected regulation is evident when a person initiates treatment because of ‘shoulds’, unhealthy guilt, or looking for social approval (Ryan and Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2001). Indeed, there is a lexical similarity between introjected regulation and demandingness in REBT (e.g. Turner, Reference Turner2016). In holding an active-directive approach, REBT practitioners are persuasive teachers (Ellis, Reference Ellis2001) and REBT has always been a direct, active, provocative and confrontational approach (Backx, Reference Backx2011; Mulhauser, Reference Mulhauser2009). According to Ryan and Deci (Reference Ryan and Deci2008) therapy can facilitate autonomy and promote an internal locus for change frequently through self-direction, self-awareness and self-regulation. Through an internal perceived locus of causality for treatment (de Charms, Reference de Charms1968; Ryan and Connell, Reference Ryan and Connell1989), clients will be more likely to engage new knowledge and behavioural change, thus resulting in more promising therapeutic outcomes (Ryan and Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2008). An active-directive counselling style using both Socratic and didactic teaching methods helps clients to become their own therapist and have preferred therapeutic goals (Dryden and Neenan, Reference Dryden and Neenan2004). Autonomy support may play a crucial role in supporting motivation and internalization (Ryan and Deci, Reference Ryan and Deci2008) towards these goals.

According to Ryan and Deci (Reference Ryan and Deci2008), intrinsically motivated individuals are more likely to be psychologically healthy individuals compared with extrinsically motivated individuals. In order to maintain such intrinsic motivations, rational beliefs may help. More importantly, in order to use rational beliefs in mental health, SDT can provide important specific concepts to lead adolescents, and both theories’ assumptions can be used in prevention interventions. For example, some studies bring motivational interviewing and SDT together in order to maintain successful treatment of alcohol- and drug-addicted clients (Markland et al., Reference Markland, Ryan, Tobin and Rollnick2005).

In sum, the RESD-A is a three-dimensional scale that measures irrational beliefs about the three BPNs, assessing irrational beliefs about autonomy, competence and relatedness in adolescents. This paper is notable in terms of its theory integration between REBT and SDT, because not only are the two theories relatable, but one can measure this interaction psychometrically, thus the integration is useful for diagnosis and treatment. Through a new psychometric tool of context-specific (ir)rational beliefs, and expanding the already established themes of irrational beliefs (e.g. achievement, approval, comfort, justice and control; Magoaşe et al., Reference Magoaşe, Stefan and David2013), this paper extends REBT and SDT theory and research. That is, this article might be considered important from theoretical (contribution to more theoretical cohesion within CBT realm), research (construction of a new tool including beliefs only) and practical standpoints (a new tool for screening, assessment and/or evaluation purposes). Finally, in this study we found that greater irrational beliefs concerning autonomy, competence and relatedness was related to markers of poorer mental health. It may be useful for education providers to think more systemically about whether their environment and service delivery offers opportunities for adolescents to challenge irrational beliefs related to the BPNs, alongside general irrational beliefs per se.

Although there are strengths and positive implications of the current study, it also has some limitations. All data are self-reported, and the RESD-A measures only irrational beliefs, not rational beliefs. Because the scale has been constructed according to the ABC model, cross-cultural variations on the RESD-A should be investigated in future research, especially to test A’s (activating events) across different cultures. Even if scenarios are carefully written, cultural norms may reveal different A’s (scenarios) than reflected in the current sample. Future research could use samples from different domains having certain, identifiable (i.e. depression, conduct disorder, etc.) clinical backgrounds.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S135246582000020X

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethics statement

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (American Psychological Association, 2010 including 2010 and 2016 amendments). Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Istanbul Arel University Research Ethics Committee.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.