At least 3 decades of research on callous-unemotional (CU) traits resulted in CU traits becoming a specifier for conduct disorder (CD) in the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) (American Psychiatric Association—APA, 2013). More recently, CU traits also became a specifier for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) in the 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) (World Health Organization, 2018). The characteristics of the limited prosocial emotions (LPE) specifier represent the most valid characteristics of CU traits (Frick & Moffitt, Reference Frick and Moffitt2010). We thus use the label CU for the LPE specifier construct in this study.

The four central features of CU are (a) lack of remorse or guilt; (b) callous, lack of empathy; (c) lack of concern about performance; and (d) shallow or deficient affect (APA, 2013, pp. 470–471). Each of these four central features is defined by more specific behaviors. The lack of remorse or guilt feature, as an example, is further defined by these specific behaviors: (a) “does not feel bad or guilty when he or she does something wrong,” (b) “shows a general lack of concern about the negative consequences of his or her actions,” (c) “is not remorseful about hurting someone,” and (d) “does not care about the consequences of breaking rules” (APA, 2013, p. 2017). CU traits are different from the symptoms of ODD and CD with CU traits predicting antisocial behavior independent of ODD and CD (Frick, Ray, Thornton, & Kahn, Reference Frick, Ray, Thornton and Kahn2014b). Even more important, high levels of CU and conduct problems (CPs) predict more severe impairment and worse prognosis than CPs alone (Frick et al., Reference Frick, Ray, Thornton and Kahn2014b).

Although many studies have examined the role of CU in serious CPs (e.g., children and adolescents with a CD diagnosis, justice system involvement, and severe disruptive behaviors—that is, ODD and CD symptoms combined) (Frick, Ray, Thornton, & Kahn, Reference Frick, Ray, Thornton and Kahn2014a), fewer studies have examined CU behaviors among young children with only ODD or oppositional defiant (OD) behaviors (Brown, Granero, & Ezpeleta, Reference Brown, Granero and Ezpeleta2017; Ezpeleta, Granero, Osa, & Domènech, Reference Ezpeleta, Granero, Osa and Domènech2015; Jezior, McKenzie, & Lee, Reference Jezior, McKenzie and Lee2016; Longman, Hawes, & Kohlhoff, Reference Longman, Hawes and Kohlhoff2016; Seijas, Servera, García-Banda, Barry, & Burns, Reference Seijas, Servera, García-Banda, Barry and Burns2018; Waller et al., Reference Waller, Gardner, Viding, Shaw, Dishion, Wilson and Hyde2014). These studies indicate that higher levels of CU are associated with higher levels of OD behavior, CU behaviors predict problems in adjustment independent of OD behaviors, and high levels of both CU and OD behaviors predict poorer outcomes than high levels of OD behaviors alone. Given the age range of our community sample (first to fourth grades) and that the children in our sample do not have a diagnosis of ODD, we will refer to the two constructs measured in the study as CU behaviors and OD behaviors.

One issue that has received less attention concerns the longitudinal associations of CU and OD behaviors across time for young children (e.g., Do CU behaviors at time one predict an increase in OD behaviors at time two, independent of OD behaviors at time one?). To provide a basis for our study, we first discuss the early development of CU and OD behaviors with a focus on temperament markers for each, along with parent-child interactional patterns that facilitate the development of CU and OD behaviors. Our purpose is to highlight unique and common temperament markers and unique and common parent-child interactions associated with CU and OD behaviors.

Development of CU behaviors in young children

CU behaviors can occur as early as age 3 and are hypothesized to develop from two temperament variables—fearless temperament and low interpersonal emotional sensitivity—in conjunction with high-risk parent-child interactions (Waller & Hyde, Reference Waller and Hyde2018, Figure 1; Waller et al., Reference Waller, Trentacosta, Shaw, Neiderhiser, Ganiban, Reiss and Hyde2016). Fearless temperament involves a low inhibition to social and non-social threat cues. Such a low arousal to threat cues interferes with learning from negative experience (i.e., negative consequences have less likelihood to reduce the additional occurrence of problematic behavior). More specifically, “low fear to threat could lead to high approach, reward dominance, and low sensitivity to punishment, which typically characterize children high on both aggression and CU behaviors” (Waller & Hyde, Reference Waller and Hyde2018, p. 13, emphasis added). Fearless temperament is thus considered a vulnerability factor for CU behaviors and CPs, an issue we revisit in the subsequent section on the vulnerability factors for OD behaviors. See also Fanti, Panayiotou, Lazarou, Michael, and Georgiou (Reference Fanti, Panayiotou, Lazarou, Michael and Georgiou2016) for a similar argument.

Figure 1. Longitudinal Measurement Model for Oppositional Defiant (OD) and Callous-Unemotional (CU) Factors.

A second temperament marker for CU behaviors involves deficits “attending to, recognizing, and responding to interpersonal emotions as early as infancy” (Waller & Hyde, Reference Waller and Hyde2018, p. 12). This second temperament marker for CU behaviors is referred to as low interpersonal emotional sensitivity (e.g., low emotional contagion, fewer verbal and vocal expressions of concern, eye contact deficits, and poor emotion recognition) (Waller & Hyde, Figure 1, p. 13). Low interpersonal emotional sensitivity in the first few years of life is considered to result in deficits in affective empathy. CU behaviors are considered to emerge from deficits in affective empathy in the context of high-risk parent-child environments (Waller & Hyde, Reference Waller and Hyde2017, Reference Waller and Hyde2018).

Parent-child interactions can either slow or promote the development of CU behaviors in vulnerable young children. Low parental warmth and high parental harshness increase the likelihood of CU behaviors, especially for children at risk due to a fearless temperament and low interpersonal emotional sensitivity (Mills-Koonce, Willoughby, Garrett-Peters, Wagner, & Vernon-Feagans, Reference Mills-Koonce, Willoughby, Garrett-Peters, Wagner and Vernon-Feagans2016; Waller & Hyde, Reference Waller and Hyde2018; Willoughby, Mills-Koonce, Propper, & Waschbusch, Reference Willoughby, Mills-Koonce, Propper and Waschbusch2013). Children's CU behaviors also appear to increase the likelihood of low parental warmth and parental harshness (Waller & Hyde, Reference Waller and Hyde2017). Even more important, CU behaviors in young children can be reduced through a change in such parenting behaviors (Bell, Shader, Webster-Stratton, Reid, & Beauchaine, Reference Bell, Shader, Webster-Stratton, Reid and Beauchaine2018; Clark & Frick, Reference Clark and Frick2016; Flom & Saudino, Reference Flom and Saudino2017; Kjøbli, Zachrisson, & Bjørnebekk, Reference Kjøbli, Zachrisson and Bjørnebekk2018; Kyranides, Fanti, Katsimicha, & Georgiou, Reference Kyranides, Fanti, Katsimicha and Georgiou2017; Waller, Gardner, & Hyde, Reference Waller, Gardner and Hyde2013).

We now briefly review the development of OD behaviors in young children. Our purpose is to highlight common and unique developmental processes for OD behaviors relative to CU behaviors.

Development of OD behaviors in young children

In the DSM-5, ODD is characterized by “a pattern of angry/irritable mood, argumentative/defiant behavior, or vindictiveness…” (APA, 2013, p. 462). The separation of irritability/anger from argumentativeness/defiance criteria is new to the DSM-5 and reflects recognition of both temperament-emotional and behavioral symptoms (APA, 2013). An established body of research—including several longitudinal studies that test mediating effects—suggests that OD behaviors often emerge from transactions between (a) heritable vulnerabilities such as trait impulsivity, including a preference for immediate rewards, actions taken without forethought, and deficiencies in self-control (which may be further magnified by low trait anxiety/fearlessness; Corr & McNaughton, Reference Corr, McNaughton, Beauchaine and Hinshaw2016); and (b) adverse family influences, which shape and maintain behavior and emotion dysregulation (Beauchaine, Zisner, & Sauder, Reference Beauchaine, Zisner and Sauder2017; Eme, Reference Eme2017; Martel, Levinson, Lee, & Smith, Reference Martel, Levinson, Lee and Smith2017; Sauder, Beauchaine, Gatzke-Kopp, Shannon, & Aylward, Reference Sauder, Beauchaine, Gatzke-Kopp, Shannon and Aylward2012; Stringaris, Maughan, & Goodman, Reference Stringaris, Maughan and Goodman2010).

Well-documented family influences include coercive parenting, harsh discipline, maltreatment, family conflict, and family stress (Deault, Reference Deault2010; Patterson, DeGarmo, & Knutson, Reference Patterson, DeGarmo and Knutson2000; Snyder, Schrepferman, & St. Peter, Reference Snyder, Schrepferman and Peter1997). Coercive, harsh, and inconsistent discipline amplify OD behaviors, which feedback to compromise parenting in a reciprocal, bidirectional fashion across time (Patterson et al., Reference Patterson, DeGarmo and Knutson2000). Such family dynamics reinforce emotional lability, emotion dysregulation, and behavior dysregulation, which interfere with adaptive socioemotional development (e.g., the development of deficits in affective empathy and inappropriate affective empathy) (Beauchaine & Zalewski, Reference Beauchaine, Zalewski, Dishion and Snyder2016). Environmental risk factors outside of the family are implicated in further progression of impulsivity and OD behaviors to CD and delinquency in later childhood and adolescence (Beauchaine, Hinshaw, & Pang, Reference Beauchaine, Hinshaw and Pang2010; Beauchaine et al., Reference Beauchaine, Zisner and Sauder2017). Children's OD behaviors also elicit reduced warmth from parents and other adults, as well as rejection by socially competent peers (Burke, Loeber, & Birmaher, Reference Burke, Loeber and Birmaher2002). Such reduced warmth from parents could then foster the development of CU behaviors (see previous section). Many studies have also demonstrated that changes in these parent-child interactions reduce OD behaviors (Kjøbli et al., Reference Kjøbli, Zachrisson and Bjørnebekk2018).

Common and unique factors in the development of CU and OD behaviors

Although the low interpersonal emotional sensitivity and subsequent deficits in affective empathy seem more specific to the development of CU than OD behaviors, it could also be possible that affective empathy could become worse in the context of the development of OD behaviors (e.g., OD behaviors result in lower levels of parental warmth with a negative impact on the child's development of appropriate affective empathy). In addition, as noted earlier, the fearless vulnerability variable is considered a risk factor for CU and OD behaviors, especially CP behaviors. To summarize, CU and OD share some overlap in the vulnerability variables and overlap even more in the problematic parenting variables (e.g., a lack of parental warmth, coercive, harsh and inconsistent discipline, lack of parental monitoring).

Given that CU and OD behaviors overlap some on vulnerabilities and share common parent-child problematic interactions, it is important to determine the longitudinal associations between CU and OD behaviors in young children. There are four possible outcomes: (a) higher levels of CU behaviors at time one predict increases in OD behaviors at time two after controlling for OD behaviors at time one (i.e., unidirectional unique effect from CU to OD); (b) higher levels of OD behaviors at time one predict increases in CU behaviors at time two after controlling for CU behaviors at time one (i.e., unidirectional unique effect from OD to CU); (c) higher levels of CU and OD behaviors at time one predict increases in the opposite construct at time two even after controlling for the other construct at time one (i.e., bidirectional unique effects between CU and OD behaviors across time); and (d) neither CU or OD behaviors predict increases in the other construct after controlling for each construct's ability to predict itself across time (i.e., no unique effects across time).

Several studies support a unidirectional effect from CU to OD behaviors in young children. Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Granero and Ezpeleta2017, Figure 1) and Ezpeleta et al. (Reference Ezpeleta, Granero, Osa and Domènech2015) found that CU behaviors at age 3 predicted an increase in OD behaviors at ages 5 and 6, whereas an ODD diagnosis at age 3 did not predict CU behaviors at ages 5 and 6, thus supporting a unidirectional effect from CU to OD behaviors across time (Jezior et al., Reference Jezior, McKenzie and Lee2016). In contrast, Waller et al. (Reference Waller, Gardner, Viding, Shaw, Dishion, Wilson and Hyde2014, Figure 1) found support for a bidirectional effect. Here, CU behaviors at age 2 predicted increases in CPs at age 3, controlling for CPs at age 2, whereas CPs at age 2 predicted increases in CU behaviors at age 3, controlling for CU behaviors at age 2. Fanti, Colins, Andershed, and Sikki (Reference Fanti, Colins, Andershed and Sikki2017) found that CU and externalizing behavior problems covaried together across three assessments during childhood (i.e., high levels of stable CU behaviors covaried with high levels of stable CPs with increasing and decreasing levels of CU behaviors associated with increasing and decreasing levels of CPs, respectively). Covariation of CU and OD behaviors across time would be consistent with no unique effects across time.

Objectives of the study

Given that the previous research with children did not yield a consistent answer to the four possible longitudinal associations between CU and OD behaviors, it is important for theoretical and clinical reasons (e.g., implications for intervention) (Clark & Frick, Reference Clark and Frick2016; Longman et al., Reference Longman, Hawes and Kohlhoff2016) to continue to investigate this question. Given the findings of Brown et al. (2016) and Ezpeleta et al. (Reference Ezpeleta, Granero, Osa and Domènech2015), the most likely outcome is a unique unidirectional effect from CU to OD behaviors. However, given the results from Waller et al. (Reference Waller, Gardner, Viding, Shaw, Dishion, Wilson and Hyde2014), as well as the shared vulnerabilities and negative parent-child interactions for CU and OD behaviors, one could also hypothesize unique bidirectional effects for children (i.e., CU behaviors predict increases in OD behaviors across time, and OD behaviors predict increases in CU behaviors across time—although the CU to OD unidirectional effect may be the most likely outcome).

The objective of our study was to evaluate the four possible longitudinal relationships between CU and OD behaviors in a community sample of Spanish children from the first to the fourth grades. The study used a cross-lagged panel design with latent variable measures of CU and OD behaviors. To date, this type of analysis has not been conducted in community samples with young children, especially with latent variable measures of the constructs. This approach allowed us to establish measurement invariance for the two constructs across time before the evaluation of the four possible outcomes. No previous studies have established measurement invariance or tested longitudinal associations between CU and OD behaviors across multiple informants and settings (home, school). In addition, with different teachers at first and fourth grade assessments, we could assess whether effects were source-independent at school. We include these various methodological features to build on the earlier studies.

Method

Participants and procedures

A total of 43 of 46 elementary schools on the island of Majorca (Spain) volunteered to participate, with 22 of these 43 schools selected randomly for inclusion (available resources allowed for recruitment of 22 schools only). Eight additional elementary schools from Madrid also volunteered to participate (eight were asked, and all eight agreed). Madrid schools were recruited to increase sample size. Potential participants were mothers, fathers, and teachers of 1,045 first grade children from the 30 Majorca and Madrid schools. A cover letter that explained the purpose of the study was given to parents, and a following parental written consent, a similar cover letter was given to teachers, who also provided written consent. The institutional review board at the university, through which data were collected, approved the protocol.

For assessments at the end of the first grade, 723 mothers and 603 fathers returned measures. At the end of the fourth grade, 377 mothers and 351 fathers returned measures (52% and 58% retention, respectively). At the first-grade assessment, 61 teachers rated an average of 11.76 (SD = 5.09, n = 743) children, with 56 teachers rating an average of 8.05 (SD = 4.30, n = 451, 61% retention) students at the fourth-grade assessment. The first and fourth grade assessments involved different teachers. There were 801 (54% boys) first grade children and 469 (53% boys) fourth grade children. Children were approximately 7 years of age at the first assessment with little variation and 10 years of age at the second assessment, also with little variation. Approximately 90% of children were Caucasian with 10% North African (schools provided age and race information at the grade level, not at the individual child level). No information was available on education and income of families.

Measures

Child and Adolescent Disruptive Behavior Inventory

(CADBI; Burns & Lee, Reference Burns and Lee2010) Mothers, fathers, and teachers completed the parent and teacher versions of the CADBI. In this study, we used the CU, OD behavior toward adults (the eight DSM-5 ODD symptoms, e.g., argues with adults, eight items) and OD behavior toward siblings and peers (the eight DSM-5 ODD symptoms, e.g., argues with siblings or peers, eight items) scales. Items were rated on 6-point scales (0 = nearly occurs none of the time; 1 = seldom occurs; 2 = sometimes occurs; 3 = often occurs; 4 = very often occurs; and 5 = nearly occurs all of the time). The four CU items were reverse-keyed, so higher scores represent higher levels of CU behaviors. Instructions asked mothers and fathers to rate symptoms in the home and community (not school) and to make ratings independently. Teachers were instructed to rate symptoms in the school only.

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for the four items on the CU scale. These items were written to match the four central features of the DSM-5 LPEs specifier.Footnote 1DSM-5 examples for each feature were also included in each item. The four items were written so that occurrence of specific behaviors represents prosocial emotions (i.e., absence of CU behaviors), whereas absence of such specific behaviors represents the presence of CU behaviors. Empirical and clinical reasons suggest wording items in an inverse manner (Ray, Frick, Thornton, Steinberg, & Cauffman, Reference Ray, Frick, Thornton, Steinberg and Cauffman2016; Seijas et al., Reference Seijas, Servera, García-Banda, Barry and Burns2018). Reliabilities for scores from the CU scale for mothers, fathers, and teachers at the first assessment were .80, .81, and .86, respectively, with values for the second assessment being .82, .82, and .85, respectively. Earlier studies support the reliability (internal consistency, test-retest, and inter-rater) and validity of scores from the CU scale (Seijas et al., Reference Seijas, Servera, García-Banda, Barry and Burns2018; Seijas et al., Reference Seijas, Servera, Garcia-Banda, Burns, Preszler, Barry and Geiser2019).

Table 1. Callous-unemotional behaviors on the parent rating scale

Note: The items were reverse-keyed so that higher scores represent higher levels of the CU behaviors. The four items on the teacher scale are identical, except that item 3 asks only about performance on school tasks.

All eight OD behavior items on the OD behaviors toward adults and the OD behaviors toward siblings/peers scales were written to match DSM-5 ODD symptoms. To simplify analyses, the OD behavior factor was defined by three parcels with 6 symptoms in the first parcel and 5 symptoms in the second and third parcels (16 OD symptoms—8 toward adults and 8 toward peers—were assigned to the three parcels; see Preszler, Burns, Litson, Geiser, & Servera, Reference Preszler, Burns, Litson, Geiser and Servera2017, Table 2 for the OD symptoms in each parcel). The 16 OD items were combined into a single construct (i.e., OD behaviors toward adults/siblings/peers) to simplify the analyses (i.e., reduce the number of parameters in the models). The correlation between the two OD behavior subscales was approximately .70 for each source.

Table 2. Fit statistics for callous-unemotional and oppositional defiant behaviors invariance analysis

Notes: Correlated residuals were used for the same indicators across time. CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; SRMR = standardized root-mean square residual.

*p < .05.

An earlier study on the 16 OD items established an invariance of like-item loadings and like-item thresholds across sources and occasions, providing justification for the use of parcels (Preszler et al., Reference Preszler, Burns, Litson, Geiser and Servera2017). Assignment of items to parcels used a procedure designed to increase the likelihood of homogeneous parcels (Little, Reference Little2013). This procedure results in the OD behavior factor being defined by 3 indicators rather than 16 indicators, thus reducing the number of parameters in the models (i.e., simplifying the model).

Reliabilities (internal consistency) for scores from the OD behavior scale for mothers, fathers, and teachers at the first assessment were .98, .98, and .99, respectively, with values for the second assessment being .98, .98, and .99, respectively. Earlier studies support reliability (internal consistency, test-retest, and inter-rater) and validity of scores from the OD scale (Bernad, Servera, Becker, & Burns, Reference Bernad, Servera, Becker and Burns2016; Burns, Servera, Bernad, Carrillo, & Cardo, Reference Burns, Servera, Bernad, Carrillo and Cardo2013; Preszler et al., Reference Preszler, Burns, Litson, Geiser and Servera2017; Servera, Bernad, Carrillo, Collado, & Burns, Reference Servera, Bernad, Carrillo, Collado and Burns2016).

Majorca versus Madrid schools

Children from Majorca schools were compared to children from Madrid schools on the OD and CU scales at the first and fourth grade assessments for ratings by mothers, fathers, and teachers. For these 12 comparisons, only one was significant: Children from Madrid had higher scores than children from Majorca on the OD measure in the fourth grade for ratings by teachers, p < .05. Children thus differed little on measures across locations.

Attrition

Missing fourth grade children were compared with present fourth grade children on the OD and CU measures in the first grade across all three sources to determine effects of attrition on the fourth-grade evaluations. Despite the large sample size, none of these eight comparisons were significant, all ps > .05. In addition, there was no differential loss of boys versus girls from the first to fourth grades and no differential loss across sites. Data were thus characterized by minimal systematic attrition.

Analytic strategy

Estimation, model identification, and model fit

We used Mplus with the robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR) for all analyses (version 8.0, Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén1998–2017). The MLR estimator uses direct information maximum likelihood to address missing information (i.e., no cases with missing information at assessment two are deleted from the analyses) and corrects for lack of normality in indicators. All analyses used effects coding to identify the models (Little, Reference Little2013). Global model fit was evaluated with the comparative fit index (CFI, study criterion ≥ .95), standardized root-mean square residual (SRMR; study criterion ≤ .05), and the root-mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; study criterion ≤ .05).

Longitudinal measurement model

Figure 1 shows the longitudinal measurement model. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to evaluate fit of the configural, weak invariance (constraints on like-indicator loadings across the two occasions), and strong invariance (constraints on like-indicator loadings and like-indicator intercepts across the two occasions) models for mothers, fathers, and teachers separately. If the decrease in CFI was less than .01 with introduction of a set of constraints, then parameters constrained equal at the particular step were considered equivalent (Little, Reference Little2013). Invariance of like-indicator loadings and like-indicator intercepts across occasions establishes measurement invariance of the CU and OD behavior factors, a prerequisite for valid longitudinal structural regression models (Little, Reference Little2013). Equality of CU and OD behavior factor means across the 3-year interval was evaluated with statistical tests. The Mplus model constraint procedure was used to perform significance tests on factor means.

Longitudinal structural regression model

Figure 2 shows the longitudinal structural regression model. This model was applied to the ratings by mothers, fathers, and teachers separately. Fit of this model is identical to fit of the strong invariance measurement model. The focus of this analysis was on cross-lagged paths (i.e., paths from OD behaviors in the first grade to CU behaviors in the fourth grade, and from CU behaviors in the first grade to OD behaviors in the fourth grade).

Figure 2. Longitudinal Structural Regression Model for Oppositional Defiant (OD) and Callous-Unemotional (CU) Factors.

Results

Missing information

The direct robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimator in Mplus does not eliminate any ratings with missing information. Covariance coverage (percentage of data present for each variance and covariance in the model with the first and fourth grade ratings) varied from 44% to 94%, 40% to 88%, and 54% to 96% for mothers, fathers, and teachers, respectively.

Longitudinal measurement model

Fit and invariance

Table 2 shows model fit information for the CU and OD behaviors longitudinal measurement model (see Figure 1). The configural model resulted in close fit for each source (all CFIs > .987, all SRMRs < .033, all RMSEAs < .044). Introduction of constraints on like-indicator loadings and like-indicator intercepts across occasions did not reduce CFIs more than .01 (the largest decrease was .003). CU and OD items thus showed measurement invariance across the 3-year interval for mothers, fathers, and teachers.

Standardized loadings

Average indicator-factor loadings for the OD factor across the two occasions for mothers, fathers, and teachers were .94 (SD = .01), .94 (SD = .02), and .97 (SD = .01), respectively. For the CU factor, average indicator-factor loadings for mothers, fathers, and teachers were .75 (SD = .08), .77 (SD = .08), and .85 (SD = .05), respectively.

Factor correlations

Table 3 shows correlations between the OD and CU factors. For interpretation of 3-year test-retest factor correlations for the same factor, it is important to remember that the first and fourth grades involved different teachers. For the OD factor, 3-year test-retest correlations for mothers, fathers, and teachers were .65 (SE = .05, p < .001), .66 (SE = .06, p < .001), and .57 (SE = .05, p < .001), respectively, and 3-year test-retest correlations for the CU factor were .52 (SE = .06, p < .001), .44 (SE = .06, p < .001), and .11 (SE = .05, p = .02), respectively. For mothers, fathers, and teachers, OD first grade to CU fourth grade factor correlations were .25 (SE = .06, p < .001), .27 (SE = .07, p < .001), and .25 (SE = .04, p < .001), respectively, and CU first grade to OD fourth grade factor correlations were .25 (SE = .05, p < .001), .28 (SE = .05, p < .001), and .27 (SE = .04, p < .001), respectively. The OD to CU and CU to OD factor correlations from the first to fourth grades were therefore almost identical within each source. The CU and OD factors also shared only a small amount of true score variance (6% to 10% for mothers and fathers, 7% to 15% for teachers). CU and OD thus represented distinct constructs with minimum overlap. Constructs with a small amount of overlap increase the potential theoretical usefulness and interpretability of longitudinal panel models (Beauchaine & Slep, Reference Beauchaine and Slep2018).

Table 3. Reliabilities (SEs) and factor correlations (SEs) for callous-unemotional and oppositional defiant factors within sources

Notes: Reliabilities are on the diagonal. Three-year test-retest factor correlations for the same factor are in boldface. Different teachers provided the ratings for first and fourth grades. All correlations significant at p < .05. CU = callous-unemotional; OD = oppositional defiant.

Factor means

Table 4 shows CU and OD factor means. For mothers and fathers, OD factor means showed a significant increase across the 3-year interval, ps < .001, latent d = 0.24 for mothers and fathers, whereas CU factor means did not show significant change, ps > .10, d = 0.06, and d = 0.09, respectively. For teachers, OD factor means did not show significant change, p > .10, d = 0.02, whereas CU factor means showed a significant increase across the interval, p < .001, d = 0.20. Again, it is important to remember that different teachers rated the children in the first and fourth grades.

Table 4. Callous-unemotional and oppositional defiant factor means

Notes: The values for the symptom measures could range from 0.00 to 5.00. Higher scores represent higher levels of CU and OD behaviors. Row means with different superscripts (a, b) differ at p < .05. d = Cohen's latent d value. CU = callous-unemotional; OD = oppositional defiant.

Longitudinal structural regression model

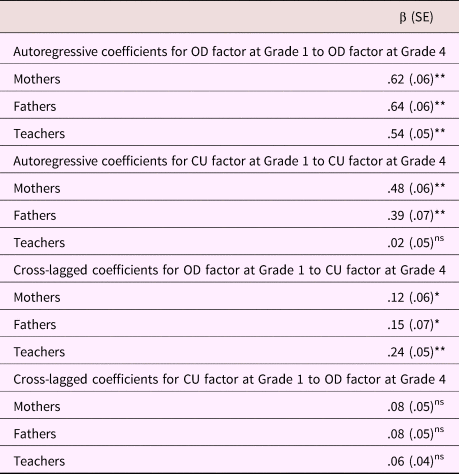

Table 5 shows partial standardized autoregressive coefficients and partial standardized cross-lagged coefficients for the three sources.

Table 5. Autoregressive and cross-lagged partial standardized regression coefficients for oppositional defiant and callous-unemotional factors from the first to fourth grades

Notes: *p < .05; **p < .01. CU = callous-unemotional; ns = nonsignificant; OD = oppositional defiant.

Autoregressive coefficients

All partial standardized autoregressive coefficients for CU and OD factors were significant (all ps < .001) with one exception. The autoregressive coefficient of CU for teachers was not significant (p > .10). With one exception, higher levels of each factor in the first grade predicted higher levels of itself in the fourth grade, controlling for cross-lagged structural paths.

Cross-lagged coefficients

All cross-lagged paths from OD behaviors in the first grade to CU behaviors in the fourth grade were significant (all ps < .05). Higher levels of OD behaviors in the first grade predicted increases in CU behaviors in the fourth grade, controlling for CU behaviors in the first grade, for all three sources. In contrast, cross-lagged paths from CU behaviors in the first grade to OD behaviors in the fourth grade were not significant (all ps > .10). Higher levels of CU behaviors in the first grade therefore did not predict increases in OD behaviors in the fourth grade, controlling for OD behaviors in the first grade for the three sources.Footnote 2

Child gender as a covariate

The longitudinal structural regression model was repeated with child gender as a covariate (i.e., CU and OD behaviors in the first grade and CU and OD behaviors in the fourth grade were regressed on child sex; see Little, Reference Little2013). All significant and nonsignificant effects remained the same (none of the partial regression coefficients changed more than 0.02).

Discussion

Our study appears to be the first to use a longitudinal panel model with multiple sources (mothers, fathers, and teachers) and latent variables to investigate longitudinal associations between CU and OD behaviors in young children. Data were collected over a 3-year interval for young children from a community sample of Spanish children. Strengths of this approach include establishment of measurement invariance of CU and OD constructs across time and establishing the consistency of findings across three informants. In addition, with different teachers for the first and fourth grade assessments, we determined whether the findings were source independent within schools. These various strengths, in conjunction with the 3-year interval, allowed for a strong evaluation of the four possible longitudinal associations between CU and OD behaviors—(a) CU behaviors uniquely predict increases in OD behaviors; (b) OD behaviors uniquely predict increases in CU behaviors; (c) CU behaviors uniquely predict increases in OD behaviors and OD behaviors uniquely predict increases in CU behaviors; or (d) no unique effects across the time interval.

Findings were the same for mothers, fathers, and teachers. Higher levels of OD behaviors in the first grade predicted increases in CU behaviors in the fourth grade after controlling CU behaviors in the first grade, whereas CU behaviors in the first grade did not predict OD behaviors in the fourth grade after controlling for OD behaviors in the first grade. For this community sample and specific time interval, OD behaviors were a statistically significant vulnerability to the development of higher levels of CU behaviors, whereas CU behaviors were not a statistically significant vulnerability to development of higher levels of OD behaviors. This same pattern of results also occurred when the three 1-year (i.e., first to second, second to third, third to fourth) and two 2-year (i.e., first to third, second to fourth) intervals were also used to test the four possible longitudinal associations between CU and OD constructs (see footnote 2).

Given the expectation for the occurrence of the opposite result (i.e., CU behaviors in the first grade predict increases in OD behaviors in the fourth grade) or perhaps the occurrence of bidirectional effects across the interval (i.e., CU behaviors predict subsequent increases in OD behaviors and OD behaviors predict subsequent increases in CU behaviors), what might explain the unexpected outcome in the current study? We turn now to this question.

If OD behaviors develop and stabilize at an earlier age than CU behaviors, then it might be easier from a psychometric standpoint for OD behaviors to predict increases in CU behaviors than for CU behaviors to predict increases in OD behaviors. In this study, OD behaviors were more stable than CU behaviors from the first to fourth grades (i.e., OD test-retest correlations: mothers = .65, fathers = .66, and teachers = .57; CU test-retest correlations: mothers = .52, fathers = .44, and teachers = .11, ps < .05). CU was thus less stable than OD behaviors for young children in this sample, thus making it easier for the OD construct to predict the CU construct across time for young children. The unexpected nature of our findings would also appear to have implications for the study of the development of CU and OD behaviors in young children. We now note these implications.

Given our results that OD behaviors confer a risk for the development of CU behaviors and other results that CU behaviors confer a risk for the development of OD behaviors (Brown et al., 2016; Ezpeleta et al., Reference Ezpeleta, Granero, Osa and Domènech2015), future studies should assess both CU and OD behaviors in young children. The simultaneous measurement of both sets of behaviors in conjunction with environmental risk factors, as well as potential mediators in longitudinal models, would allow a better understanding of the longitudinal associations of these two constructs in early childhood. The formulation of a common model for the development of CU and OD behaviors in young children, especially a model for the transition from vulnerabilities of infancy to CU/OD behaviors to CU traits and ODD diagnosis, should yield a richer understanding of the CU and OD constructs (e.g., identification of common and unique etiological processes, as well as common and unique outcomes).

Our new measure of CU traits (i.e., a measure of the DSM-5 LPE specifier for CD and the ICD-11 LPE specifier for ODD) could be useful for future studies on CU and OD constructs, given its brief nature along with its positive psychometric properties (Seijas et al., Reference Seijas, Servera, García-Banda, Barry and Burns2018, 2019). One important property of this new measure is good discriminant validity vis-à-vis measures of ODD (i.e., factor correlations from .25 to .39 in the current study vs. factor correlations of .73 to .89 between CU and CPs as reported in Kjøbli et al., Reference Kjøbli, Zachrisson and Bjørnebekk2018 and Waller et al., Reference Waller, Gardner, Viding, Shaw, Dishion, Wilson and Hyde2014). Strong discriminant validity between the CU and OD behaviors allows for easier identification of common and unique etiological processes and outcomes for CU and OD dimensions. Finally, treatment studies of disruptive behaviors in young children should measure both CU and OD behaviors given increasing evidence that CU behaviors are influenced by similar parenting variables as OD behaviors in young children (e.g., Kjøbli et al., Reference Kjøbli, Zachrisson and Bjørnebekk2018; Waller & Hyde, Reference Waller and Hyde2018; Willoughby et al., Reference Willoughby, Mills-Koonce, Propper and Waschbusch2013). Such treatment studies could then determine which aspects of treatments most impact which symptom sets within certain developmental periods (Kyranides et al., Reference Kyranides, Fanti, Katsimicha and Georgiou2017). As suggested earlier, the development of a common model for the development of CU and OD behaviors might yield a better understanding of the constructs, with new implications for prevention and treatment (Waller & Hyde, Reference Waller and Hyde2018, Figure 1).

Although our study has several strengths, there are also limitations to note. One involves an inherent feature of the longitudinal panel model. Although this model is considered ideal to evaluate cross-lag associations between different constructs across measurement occasions, the model removes overlap between the two constructs at occasion one in order to determine unique effects of each construct on the other across occasions. This process (removing overlap between constructs A and B at occasion one) may weaken or obscure prospective relations between two constructs—especially when their overlap represents common etiological causes/mechanisms (McDonough-Caplan, Klein, & Beauchaine, Reference McDonough-Caplan, Beauchaine and Martel2018). Fortunately, the overlap between OD and CU behaviors in the current study was small (6% to 15% shared variance), but it is still important to note this issue.

Findings could also be specific to our community sample of young Spanish children. It is not clear whether similar results would be obtained with at-risk or clinical samples along with samples of different ages or children from different countries. For example, Brown et al. (Reference Brown, Granero and Ezpeleta2017) and Ezpeleta et al. (Reference Ezpeleta, Granero, Osa and Domènech2015) found opposite results to our study with their sample of young Spanish children at a different age (i.e., ratings of CU predicted an increase in ODD symptoms after controlling for an ODD diagnosis, whereas the ODD diagnosis did not predict CU ratings after controlling for CU from ages 3 to 6 years). It is thus important to continue to examine relations between CU and OD behaviors with different samples and across different developmental periods to better understand this issue (i.e., CU as a vulnerability to OD vs. OD as a vulnerability to CU vs. a bidirectional effects). Although we obtained the same results controlling for child gender, our sample at time two was not large enough for separate analyses for boys and girls. Final limitations are lack of socioeconomic and educational information on parents.

Our findings and others (Beauchaine et al., Reference Beauchaine, Hinshaw and Pang2010, Reference Beauchaine, Zisner and Sauder2017; Beauchaine & McNulty, Reference Beauchaine and McNulty2013; Eme, Reference Eme2017; Waller et al., Reference Waller, Gardner and Hyde2013) suggest that CU behaviors are distinct from OD behaviors. Integration of models for the development of CU and OD behaviors should offer insights into etiology, assessment, and treatment of CU and OD behaviors and therefore provide a more integrative model of CU and OD behaviors (Hawes, Price, & Dadds, Reference Hawes, Price and Dadds2014; Kjøbli et al., Reference Kjøbli, Zachrisson and Bjørnebekk2018; Waller & Hyde, Reference Waller and Hyde2018). Such models might also help address the unexpected results of the current study.

Acknowldgments

The authors thank Cristina Trias and Cristina Solano for their help in data collection.

Financial support

Two Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness grants, PSI2011-23254 and PSI2014-52605-R (Spanish Government), and a predoctoral fellowship co-financed by the European Social Fund and the Balearic Islands Government (FPI/1451/2012) supported this research.