Emotions are important for the survival of animals and human beings, and they participate in a variety of behaviors, including approach and withdrawal or fight-or-flight behaviors, as well as in social communication. From a motivational perspective, emotion is considered as a behavioral tendency to approach or avoid a stimulus or a situation (Lang et al., Reference Lang, Bradley, Cuthbert, Lang, Simons and Balaban1997; Seidel et al., Reference Seidel, Habel, Kirschner, Gur and Derntl2010). This tendency is based on two motivational systems, the appetitive system (related to approach behaviors) and the defensive system (related to fight-or-flight behaviors). Accordingly, two basic bipolar dimensions can describe emotion, the affective valence -ranging from pleasant/appetitive motivation to unpleasant/avoidance motivation- and arousal -ranging from calm to exciting, reflecting the intensity of motivational activation (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Codispoti, Cuthbert and Lang2001; Lang & Bradley, Reference Lang and Bradley2010; Lang et al., Reference Lang, Bradley, Cuthbert, Lang, Simons and Balaban1997). Emotional responses appear in the three response systems, cognitive/subjective, behavioral and physiological (Lang, Reference Lang and Franks1969), and previous research has widely shown that activity in these systems correlates with affective valence and/or arousal (see Lang et al., Reference Lang, Greenwald, Bradley and Hamm1993, for a two-factor solution resulting from the factorization of several subjective, behavioral, and physiological variables).

However, humans are not only emotional, but also social beings. Their behavior depends also on their social environment, and, therefore, their emotions may be influenced by several factors related to the social context (Adolphs, Reference Adolphs2009). A number of studies have shown that the social content of the stimuli influences the emotional responses. For example, Scherer and Tannenbaum (Reference Scherer and Tannenbaum1986) found that most of the emotional events in our lives are connected to relationships with family and friends. A recent study has revealed that aversive social stimuli evoke more subjective negative affect than non-social stimuli; moreover, individuals who are more sensitive to social rejection are less successful in the regulation of emotional responses provoked by aversive social stimuli (Silvers, Reference Silvers2013). In this line, Dan-Glauser and Scherer (Reference Dan-Glauser and Scherer2011) have found that negative pictures related to the violation of social norms are rated with lower affective valence and higher arousal than other non-social, unpleasant pictures (e.g., snake and spider pictures). Social content also exerts an effect on behavioral measurements. For example, social pictures are viewed longer than non-social pictures, as reported by Sakaki et al. (Reference Sakaki, Niki and Mather2012).

Several psychophysiological studies have also shown the influence of the social content on how people process and react to emotional stimuli. For example, skin conductance response has been found to be influenced by the social content of affective film-clips (Britton, Taylor et al., Reference Britton, Phan, Taylor, Welsh, Berridge and Liberzon2006). In the same vein, Kosonogov et al. (Reference Kosonogov, Sánchez-Navarro, Martínez-Selva, Torrente and Carrillo-Verdejo2016) have found that skin conductance response increased as the social content of the pleasant pictures did. Studies using facial electromyographic (EMG) activity measurements have revealed differences in the activity of several facial muscles depending on the social content of the affective stimuli. For example, Fridlund et al. (Reference Fridlund, Sabini, Hedlund, Schaut, Shenker and Knauer1990) found that participants smiled more in a high-sociality than in a low-sociality imagery task, and Philipp et al. (Reference Philipp, Storrs and Vanman2012) showed that pleasant pictures elicited greater zygomaticus major EMG activity in the presence of virtual humans, though the pleasantness ratings of the pictures were unaffected by the presence of the virtual humans. The study of event-related brain potentials (ERPs) also reveals a differential activity depending on the social content of the affective stimuli. Proverbio et al. (Reference Proverbio, Zani and Adorni2008) found a larger left parietal N2 component evoked by social scenes in comparison to landscapes that may be related to the greater automatic attention to pictures depicting social scenes (e.g. human faces and bodies). In this line, Carretié et al. (Reference Carretié, Kessel, Carboni, López-Martín, Albert, Tapia, Mercado, Capilla and Hinojosa2013) demonstrated that high social stimuli (emotional facial expressions) provoke greater exogenous attention than non-facial pictures (scenes). Moreover, positive faces provoke greater attentional capture, as shown by larger amplitudes of the N170 ERP component, than negative faces. Authors note that this positivity offset -a processing bias that facilitates the processing of appetitive stimuli (Cacioppo & Gardner, Reference Cacioppo and Gardner1999)- may be important in social interaction.

This growing interest in the influence of the social components of the affective stimuli on the emotional response has also led to studying the brain regions supporting the processing of these components through functional neuroimaging techniques. These studies have found that affective pictures depicting social content elicit greater activation of several neural structures, including the fusiform gyrus (Geday et al., Reference Geday, Gjedde, Boldsen and Kupers2003) -an extra-striate area related to face processing- the superior temporal sulcus (Norris et al., Reference Norris, Chen, Zhu, Small and Cacioppo2004) -a region related to the perception of social signals (e.g., emotional facial expressions and body images) - and the amygdala (Silvers, Reference Silvers2013) -related to emotional processing. In addition, the data obtained by Frewen et al. (Reference Frewen, Dozois, Neufeld, Densmore, Stevens and Lanius2011) reveal that social emotional processing, regardless of affective valence, recruits brain regions involved in social processing, such as the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate/precuneus, bilateral temporal poles, bilateral temporoparietal junction and right amygdala. Cacioppo and co-workers (2009) showed that lonely individuals are characterized by greater activation of the visual cortex to pictures of people than of objects. Thus, behavioral and physiological studies give support to the relationship between emotion and social content with regard to the reactions of the observers.

A limitation of most previous studies has been the use of the variable social content as a qualitative constant following an “all or nothing” principle, that is, the stimuli or conditions are usually separated into two categories: Social and non-social (e.g., Britton, Phan, et al., Reference Britton, Phan, Taylor, Welsh, Berridge and Liberzon2006; Norris et al., Reference Norris, Chen, Zhu, Small and Cacioppo2004; Proverbio et al., Reference Proverbio, Zani and Adorni2008). These studies have usually employed either faces or pictures depicting, at least, one human being as social stimuli (e.g., Carretié et al., Reference Carretié, Kessel, Carboni, López-Martín, Albert, Tapia, Mercado, Capilla and Hinojosa2013; Harvey et al., 2007; Norris et al., Reference Norris, Chen, Zhu, Small and Cacioppo2004). However, recent research has also found that human reactions to emotional social stimuli (pictures depicting faces and bodies) vary depending on whether these stimuli appear isolated or in a social scene (Kret et al., Reference Kret, Roelofs, Stekelenburg and de Gelder2013). The social versus non-social categorization of the social variable could lead, therefore, to the masking of several physiological changes and subjective responses, resulting in a loss of findings related to the influence of the social content of the affective stimuli on emotional response.

Hence, it is necessary to explore whether variations in the level of social content of the affective stimuli result in differences in the emotional responses they provoke. This question could be answered by incorporating a division of the social stimuli according to the number of persons depicted by the pictures, as proposed by previous research (Wardle & de Wit, Reference Wardle and de Wit2012). This approach would provide more precise data about the effects of social stimuli.

The main goal of this research was, therefore, to study the influence of the social content of the pictures on the affective valence and arousal ratings. For this purpose, we categorized our emotional stimuli according to their social content –i.e., whether they depicted one person, two or more interacting people, or did not display any people. Following previous research (e.g., Carretié et al., Reference Carretié, Kessel, Carboni, López-Martín, Albert, Tapia, Mercado, Capilla and Hinojosa2013; Dan-Glauser & Scherer, Reference Dan-Glauser and Scherer2011; Norris et al., Reference Norris, Chen, Zhu, Small and Cacioppo2004), we expected an effect of social content on the subjective evaluation (affective valence and arousal) of the pictures. Specifically, pictures with greater social content were predicted to strengthen the affective valence ratings, especially for pleasant and unpleasant pictures. We also expected higher arousal ratings for greater social content, independently of the picture category (emotional content) of the pictures.

Following our previous research (Kosonogov et al., Reference Kosonogov, Sánchez-Navarro, Martínez-Selva, Torrente and Carrillo-Verdejo2016; Kosonogov, Martínez-Selva, Carrillo-Verdejo, et al., Reference Kosonogov, Martínez-Selva, Carrillo-Verdejo, Torrente, Carretié and Sánchez-Navarro2019; Kosonogov, Martínez-Selva, Torrente, et al., Reference Kosonogov, Martínez-Selva, Carrillo-Verdejo, Torrente, Carretié and Sánchez-Navarro2019), in order to check whether the selection of the pictures properly reflected their social content, we constructed a perceived social interaction scale ranging from 1 (no interaction) to 9 (high interaction). Consequently, we expected that the greater the social content of the pictures, the higher the social interaction ratings.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 161 Psychology student volunteers (119 females) aged between 18 and 35 years (M = 21.10, SD = 3.04). All participants were selected from University of Murcia and received course credits for participation.

Stimuli

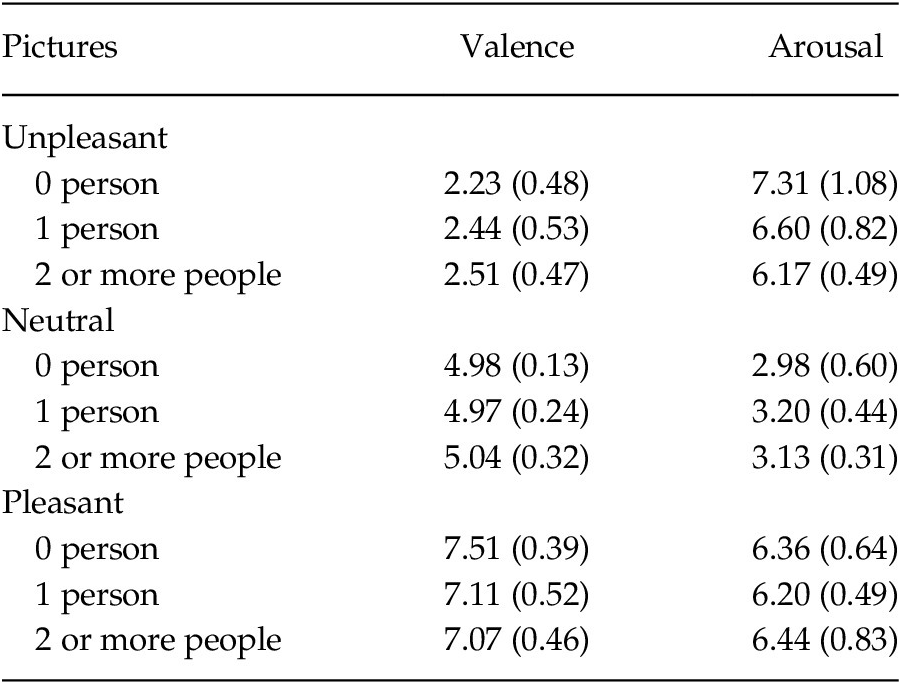

The experimental stimuli consisted of 200Footnote 1 affective pictures: 146 were selected from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang et al., Reference Lang, Bradley and Cuthbert2008), 34 were selected from the EmoMadrid affective picture databaseFootnote 2, and 20 additional neutral pictures depicting social interaction were downloaded from the Internet, since the IAPS and the EmoMadrid do not contain enough pictures with this content (Table 1 shows the mean values and standard deviations of the pictures selected from both databases). Seven university scholars were invited to rate the pictures downloaded from the Internet, and a picture was included in the experimental set only if at least 4 out of 7 subjects agreed that the content was neutral. Pictures were chosen to comprise 9 categories varying in affective valence (unpleasant, neutral, and pleasant) and social content (0 people, 1 person, and 2 or more interacting people). Each of the 9 categories contained 20 to 27 pictures. We also selected 4 additional pictures from the IAPS used at the beginning of the study as training trials.

Table 1. Affective Valence and Arousal of the Selected Pictures according to the IAPS and the EmoMadrid (Means and Standard Deviations)

Procedure

The evaluation of the pictures was carried out in two sessions, and each subject was randomly assigned to one of them. In each session, the pictures were pseudo-randomly distributed along 200 trials such that two consecutive pictures of the same emotional and social category were not allowed. The order of presentation was the same for the two sessions. The pictures were presented on a large projection screen (1.5 × 2 m) via an LCD projector. Eighty subjects in the first session and 81 in the second session were seated in a large room at a distance between 3 and 10 m from the screen. We did not equalize the distance to the screen because picture size does not influence subjective ratings (Sánchez-Navarro et al., Reference Sánchez-Navarro, Martínez-Selva, Román and Torrente2006). Each session lasted approximately 120 min, with a 10 min break in the middle of the session in order to avoid participants’ fatigue. To ensure that subjects performed the task accurately, four training trials were administered at the beginning of the study, and questions regarding the task were answered. Each picture was presented for 6 s. After picture offset, subjects had 20s to rate the picture in a paper-and-pencil questionnaire. For each picture, participants were asked to rate affective valence, arousal and social interaction. Affective valence and arousal were rated on a 9-point Likert scale for each dimension, with 9 representing a high rating (i.e., very pleasant, high arousal), and 1 a low rating (i.e., very unpleasant, and low arousal). Likewise, perceived social interaction was also rated on a 9-point Likert scale, with 9 representing high social interaction, and 1 representing no social interaction. The instruction to the subjects regarding this scale was to rate the interaction depicted in the picture.

Data analysis

All the statistical analyses were conducted with the PASW 19 package (IBM, USA). Each subjective rating was analyzed by a repeated measures ANOVA, 3 (Picture category: Unpleasant, neutral and pleasant) × 3 (Social content: Without people, 1 person, and 2 or more people), with both Picture category (emotional content) and Social content as within-subject variables. When appropriate, a Greenhouse-Geisser adjustment of the degrees of freedom was used to correct any potential inflation of the reported probability values (Bagiella et al., Reference Bagiella, Sloan and Heitjan2000). For the main statistical tests, we obtained a measure of the effect size (partial eta-squared, ηp2). Paired comparisons were performed with a Bonferroni correction (Keselman, Reference Keselman1998). We used a .05 level of significance for all the statistical analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 2 shows a summary of the descriptive statistics for each picture category (the means and standard deviations of each picture can be found in Appendix A for all participants, in Appendix B for females, and in Appendix C for males). As shown in Figure 1, affective valence and arousal ratings of all the pictures used in the study showed a typical U-shaped curve. The subjective ratings of the 180 pictures selected from the IAPS and the EmoMadrid databases were highly and positively correlated with the original IAPS and EmoMadrid ratings for both affective valence (r = .95, p < .001) and arousal (r = .82, p < .001). The t-tests did not reveal any difference between our data and those obtained by Lang et al. (Reference Lang, Bradley and Cuthbert2008) (all ps > .05). Additionally, we did not find gender differences in general values of affective valence, arousal, and social interaction ratings (all ps > .05), although some comparisons yielded significant gender differences in affective valence (Table 2)Footnote 3. We found significant correlations neither between affective valence and social interaction, nor between arousal and social interaction (all ps > .05).

Table 2. Means (and Standard Deviations) of the Subjective Ratings for Each Picture Category

Note. The values indicated with a specific superscript (a, b, c, etc) differed significantly (p < .05). For example, the valence to unpleasant pictures in men differed significantly from the valence to unpleasant pictures in women, as noted with a.

Figure 1. Affective Valence, Arousal and Social Interaction Ratings obtained in Our Study Note. One point represents one picture.

Social interaction

As expected, the evaluation of the Social content of the affective pictures through the perceived social interaction ratings revealed a significant effect of the social content, F(2, 320) = 1,998.8, p < .0001, ηp2= .93. Pictures with two people obtained higher ratings in social interaction than pictures with one person, t(160) = 43.8, p < .001, and than pictures without people, t(160) = 49.3, p < .001); in turn, pictures with one person were rated with higher social interaction than pictures without people, t(160) = 5.8, p < .001).

Table 3. Social Interaction Ratings of the Pictures depending on the Social Content (Means and Standard Deviations)

Note. The values indicated with a specific superscript (a, b, c, etc) differed significantly (p < .05). For example, the social interaction to 1 person pictures in men differed significantly from the social interaction to 1 person pictures in women, as noted with a.

Affective valence

We found a significant main effect of Picture category (emotional content), F(2, 159) = 2,243.1, p < .001, ηp2 = .93. Paired comparisons showed that pleasant pictures were rated with higher affective valence than neutral, t(160) = 37.0, p < .001, and than unpleasant pictures, t(160) = 52.3, p < .001), and, in turn, neutral pictures were rated with higher affective valence than unpleasant pictures, t(160) = 43.7, p < .001.

We also found a significant main effect of Social content on affective valence ratings, F(2, 159) = 43.4, p < .001, ηp2 = .21. However, these effects were qualified by a Picture category (emotional content) × Social content significant interaction, F(4, 157) = 71.7, p < .001, ηp2 = .31. Post-hoc comparisons (with the Bonferroni correction) showed that unpleasant pictures with two or more people were rated as more unpleasant (lower affective valence) than unpleasant pictures with one person, t(160) = 6.8, p < .001, and than pictures without people, t(160) = 12.6, p < .001. In turn, unpleasant pictures with one person were rated as more unpleasant (lower affective valence) than unpleasant pictures without people, t(160) = 8.2, p < .001.

Regarding neutral pictures, pictures with one person were rated with higher affective valence than pictures without people, t(160) = 6.4, p < .001 and also rated with higher affective valence than pictures depicting two or more people, t(160) = 6.5, p < .001. Pleasant pictures with two or more people, t(160) = 9.8, p < .001, as well as pleasant pictures without people, t(160) = 9.1, p < .001, were rated with higher affective valence than pleasant pictures with one person.

Arousal

Statistical analyses revealed a significant main effect of Picture category (emotional content), F(2, 159) = 1009.1, p < .001, ηp2 = .86. Paired comparisons showed that neutral pictures were rated with lower arousal ratings than both pleasant, t(160) = 37.7, p < .001, and unpleasant pictures, t(160) = 36.8, p < .001, whereas pleasant and unpleasant pictures did not differ, t(160) = 1.3, p = .52.

We also found a significant main effect of Social content on arousal ratings, F(2, 159) = 109.2, p < .001, ηp2 = .41. Pictures depicting two people were rated with higher arousal ratings than pictures with one person, t(160) = 7.8, p < .001, and than pictures without people, t(160) = 14.1, p < .001. In turn, pictures with one person were rated with higher arousal ratings than pictures without people, t(160) = 7.4, p < .001.

A Picture category (emotional content) × Social content significant interaction was also found, F(4, 157) = 64.0, p < .001, ηp2 = .29. Post-hoc comparisons (with the Bonferroni correction) found that unpleasant pictures depicting two or more people were rated with higher arousal ratings than both unpleasant pictures with one person, t(160) = 6.8, p < .001, and unpleasant pictures without people, t(160) = 9.8, p < .001; in turn, unpleasant pictures with one person were rated with higher arousal ratings than pictures without people, t(160) = 3.7, p < .001.

For neutral pictures, paired comparisons revealed that neutral pictures depicting one person were rated with higher arousal ratings than both neutral pictures without people, t(160) = 14.2, p < .001, and neutral pictures with two or more people, t(160) = 5.0, p < .001; neutral pictures with two or more people were rated with higher arousal than neutral pictures without people, t(160) = 10.7, p < .001. Pleasant pictures depicting two or more people were rated higher in arousal than both pleasant pictures without people, t(160) = 7.3, p < .001, and pleasant pictures with one person, t(160) = 11.9, p < .001, and pleasant pictures without people were also rated with higher arousal than pleasant pictures with one person, t(160) = 3.1, p = .007.

Discussion

The main aim of this research was to study the effects of the social content on the subjective evaluation of affective pictures. Our data on affective valence and arousal were similar to the findings obtained in previous studies (Lang et al., Reference Lang, Bradley and Cuthbert2008; Moltó et al., Reference Moltó, Montañés, Poy, Segarra, Pastor, Tormo, Ramírez, Hernández, Sánchez, Fernández and Vila1999; Moltó et al., Reference Moltó, Segarra, López, Esteller, Fonfría, Pastor and Poy2013; Vila et al., Reference Vila, Sánchez, Ramírez, Fernández, Cobos, Rodríguez and Moltó2001). Affective valence monotonically varied with picture category (emotional content) -pleasant pictures received the highest ratings whereas the unpleasant pictures received the lowest ratings- and arousal ratings were higher for picture category (emotional content) -pleasant and unpleasant pictures- than for neutral pictures. These data are in agreement with previous research showing a two-dimensional structure of emotion (Lang et al., Reference Lang, Greenwald, Bradley and Hamm1993; Sánchez-Navarro et al., Reference Sánchez-Navarro, Martínez-Selva, Torrente and Román2008). In this model, the affective valence dimension is related to the approach or avoidance motivation, whereas the arousal dimension relates to the power or strength of such motivation (Lang et al., Reference Lang, Bradley, Cuthbert, Lang, Simons and Balaban1997).

As expected, the social content of the pictures influenced both the affective valence and arousal ratings of the pictures. In the case of unpleasant pictures, those depicting one person and two or more people were rated as more unpleasant than unpleasant pictures without people. Moreover, pictures depicting two or more people were rated as the most unpleasant. Accordingly, the greater the social content of negative stimuli, the greater the perceived unpleasantness as reflected by affective valence ratings. Additionally, this result is in agreement with some previous studies reporting that social unpleasant stimuli provoke greater psychophysiological responses than non-social unpleasant ones (Kosonogov et al., Reference Kosonogov, Sánchez-Navarro, Martínez-Selva, Torrente and Carrillo-Verdejo2015; Silvers, Reference Silvers2013), as well as higher unpleasantness and arousal ratings (Dan-Glauser & Scherer, Reference Dan-Glauser and Scherer2011). Similar results were also found regarding pleasant pictures, since those depicting two or more people were judged more pleasant than pictures displaying only one person. These data showed an increase of pleasantness as the social content of the positive pictures augmented, and are in agreement with psychophysiological evidences revealing facial EMG changes related to the social content of the affective pictures. For example, previous research has found greater zygomaticus major activity (a muscle previously related to positive affect; see Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Codispoti, Cuthbert and Lang2001, and Lang et al., Reference Lang, Greenwald, Bradley and Hamm1993) when subjects view happy social scenes -in comparison to unpleasant scenes- whereas it does not differentiate between isolated emotional faces (Kret et al., Reference Kret, Roelofs, Stekelenburg and de Gelder2013). Moreover, the results found by Wardle and de Wit (Reference Wardle and de Wit2012) revealed greater zygomaticus major EMG activity and less corrugator EMG activity provoked by social pleasant pictures (two or more people in the scene) in comparison to non-social pleasant ones. Gros et al. (Reference Gros, Hawk and Moscovitch2009) showed that social content can modulate the psychophysiological reactions of anxious patients. These findings suggest that the social content of the affective stimuli provoke differential facial EMG changes that have been considered tactic responses and might be related, for example, to social functions (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Codispoti, Cuthbert and Lang2001). However, we must be cautious in the interpretation of our results on pleasant pictures because pleasant pictures without people were rated with higher affective valence than pictures depicting one person, and, therefore, further research is required to explain these differences.

Additionally, and according to our hypothesis, arousal was linearly related to social content: The more people in a picture, the higher the arousal rating it received. This pattern was found for emotional, pleasant and unpleasant pictures, but not for neutral pictures. These results support the data obtained by Scherer and Tannenbaum (Reference Scherer and Tannenbaum1986) showing that the most emotional or arousing events in our life are related to relationships with other people. Previous psychophysiological findings (e.g., Cuthbert et al., Reference Cuthbert, Schupp, Bradley, Birbaumer and Lang2000; Lang et al., Reference Lang, Greenwald, Bradley and Hamm1993; Sánchez-Navarro et al., Reference Sánchez-Navarro, Martínez-Selva, Torrente and Román2008) suggest that high arousal pictures -pleasant and unpleasant- provoke higher physiological arousal related to orienting and attention (as measured by skin conductance response), demand greater processing resources (as revealed by the cortical late positive component of the ERPs), are viewed for longer and provoke higher interest in the observer than low arousal, neutral pictures. In the same vein, Proverbio et al. (Reference Proverbio, Zani and Adorni2008) have shown that viewing pictures depicting social scenes (e.g., human interaction) provoke greater automatic attention, as revealed by cortical activity reflected in ERP components. Our results on arousal agree with these findings, revealing that the greater the social content of the affective stimuli, the higher the arousal perceived, and they also support previous research showing larger skin conductance responses provoked by greater social content (Kosonogov et al., Reference Kosonogov, Sánchez-Navarro, Martínez-Selva, Torrente and Carrillo-Verdejo2016).

As expected, perceived social interaction ratings depended on the number of people in the pictures, showing that the more people in a picture, the higher the scores on social interaction. Overall, our data are in agreement with previous neuroimaging findings that suggest that several neural structures involved in emotional processing are also related to the social value of the stimuli (e.g., Britton, Phan, et al., Reference Britton, Phan, Taylor, Welsh, Berridge and Liberzon2006; Norris et al., Reference Norris, Chen, Zhu, Small and Cacioppo2004). In addition, these results are in accordance with hypotheses that have related the development of complex human social interaction to the evolution of some brain structures as a result of evolutionary pressure (Dunbar, Reference Dunbar1998).

It has previously been proposed that emotions depend on two motivational systems of the brain -appetitive and aversive (Lang et al., Reference Lang, Bradley, Cuthbert, Lang, Simons and Balaban1997). In addition, emotions may also be influenced by the social context (Bradley et al., Reference Bradley, Codispoti, Cuthbert and Lang2001). In the process of natural selection, it has been more important for survival to display a faster and stronger reaction to unpleasant signals of the environment than to pleasant stimuli. This negativity bias is a robust psychological phenomenon that has received wide support (Cacioppo & Gardner, Reference Cacioppo and Gardner1999). In addition, according to the positivity offset hypothesis (Cacioppo & Gardner, Reference Cacioppo and Gardner1999) it has been proposed a better processing of positive social stimuli (e.g., Carretié et al., Reference Carretié, Kessel, Carboni, López-Martín, Albert, Tapia, Mercado, Capilla and Hinojosa2013). According to our results, these effects might be modulated by the social content of the stimuli, in such a way that the higher the social content of the stimuli, the stronger the reaction displayed, a hypothesis that needs to be explored by future research.

Our results could have practical implications for the treatment of several affective pathologies. For example, the finding that pleasant pictures with two or more people provoke more arousal than pleasant pictures without people can potentially be used in exposure therapies for the treatment of social anxious patients or depressive patients.

Future research should resolve some limitations of our study. Thus, the number of participants could be enlarged or even a standardization study could be conducted in order to have normative values on social interaction scale. In future studies researchers should also balance the gender ratio and use several presentation orders to avoid the halo effect (Saal et al., Reference Saal, Downey and Lahey1980). Another question to explore would be the selection of the pictures with social content. In our study, we used the majority rule (4 versus 3 experts) to include a picture in the category of social pictures; however, another rule of selection could potentially have led to other results.

Overall, our results reveal that the social content of a picture influences the viewer’s subjective evaluation of affective valence and arousal. Whether social content also influences the subjects’ behavioral response and physiological reactions is beyond the scope of this study and should be addressed by future research, though findings from previous research seem to support this hypothesis (e.g., Kosonogov et al., Reference Kosonogov, Sánchez-Navarro, Martínez-Selva, Torrente and Carrillo-Verdejo2016; Wardle & de Wit, Reference Wardle and de Wit2012). Further studies should also establish the neural structures supporting the processing of social stimuli varying in affective content.

Acknowledgments.

The study was supported by a FPU fellowship of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports of Spain in 2012-2015

Appendix

Appendix A. Subjective Ratings (Mean and Standard Deviation) of the Pictures selected from the IAPS and EmoMadrid Databases in Our Experimental Sample (All Participants)

Appendix B. Subjective Ratings (Mean and standard Deviation) of the Pictures Selected from the IAPS and EmoMadrid Databases in our Experimental Sample (Female Participants)

Appendix C. Subjective Ratings (Mean and Standard Deviation) of the Pictures Selected from the IAPS and EmoMadrid Databases in Our Experimental Sample (Male Participants)