A cardiac rhabdomyoma can be diagnosed prenatally, as an incidental finding in the fetal cardiology clinic, or may be a finding in the postnatal work-up for tuberous sclerosis. Cardiac tumours are rare, with the incidence of the primary tumours of the heart and pericardium, reported from autopsy studies of patients of all ages, varying from 0.17 to 28 in 10,000.Reference McAllister1 In children, the most frequent histological types are rhabdomyomas, accounting for three-fifths of cases, with teratomas making up one-quarter, and fibromas one-eighth. The course during fetal life depends on the growth and size of the tumours. Large masses can cause haemodynamic obstruction and subsequent cardiac failure, as well as fetal hydrops or tachyarrhythmia.Reference Pipitone, Mongiovi, Grillo, Gagliano and Sperendeo2–Reference Black, Kadletz, Smallhorn and Freedom7 While these life threatening complications in the perinatal period are relatively rare, cardiac complications such as disturbances of rhythm, as well as the association with tuberous sclerosis,Reference Tworetzky, Mc Elhinney and Margossian8 represent the crucial point for the long-term outcome.Reference Fesslova, Villa, Rizzuti, Mastrangelo and Mosca9 Cardiac rhabdomyomas are reported to be associated with tuberous sclerosis in up to seven-eighths of patients,Reference Harding and Pagon10, Reference Groves, Fagg, Cook and Allan11 and up to four-fifths of patients with tuberous sclerosis have cardiac rhabdomyomas.Reference Beghetti, Gow, Haney, Mawson, Williams and Freedom12 The association with tuberous sclerosis, therefore, should form an important issue during the prenatal counselling of parents. Our aim was to analyze the data of patients with cardiac rhabdomyomas, establishing their long-term cardiac and neurological outcomes in order to allow comprehensive prenatal counselling.

Methods

This multi-center retrospective study was performed using the data from all patients with an echocardiographic diagnosis of cardiac rhabdomyoma encountered at our institutions from August, 1982, to September, 2007. The criteria for diagnosis included the demonstration of the presence of multiple intracardiac tumours with characteristic echocardiographic appearances, in the absence of known malignant disease, or the existence of one or more tumours in association with tuberous sclerosis. These criteria were based on the information that fibromas and myxomas are invariably solitary tumours, and on the very strong association between rhabdomyomas and tuberous sclerosis. An additional most important criterion was the evolution of the tumours, which is their tendency to regress and disappear in time.

The patients with a prenatal diagnosis had been referred for fetal echocardiography due to a suspicion of a cardiac anomaly on obstetrical ultrasound. The patients with postnatal diagnosis were referred either for detection of cardiac tumours in the presence of otherwise proven tuberous sclerosis, or were investigated for cardiac symptoms such as a murmur or disturbances of cardiac rhythm in an otherwise healthy child.

The patients were followed up by means of echocardiography over 3 months to 18 years, with a mean period of 4.8 years. The age at detection, and the number and the size of nodules at the time of detection, were documented, together with their evolution on follow-up echocardiography and associated cardiac complications.

We reviewed the medical records of all patients known to have cardiac rhabdomyoma to ascertain the major criteria for the diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis, evaluating findings related to the central nervous system, the skin, renal angiomyofibromas, and retinal harmatomas. We documented the incidence of tuberous sclerosis, establishing any statistical association with the number of tumours and their exact cardiac location. Our hypothesis was that certain locations were more likely to be related to tuberous sclerosis than others. The potential association to the number of tumours was analyzed by using Fisher’s exact test, with results presented as p-value and Odd’s ratio for 95% confidence intervals.

In the subgroup with precise neurological follow-up, we documented neurodevelopmental complications in terms of the presence of epilepsy, its control, the number of anti-epileptic drugs required, the presence of developmental delay, requirement for special school, and any associated behavioral issues. The assessment of the severity of the developmental delay as mild, moderate, or severe was based on the developmental evaluation by paediatric neurologists.

Results

We identified 73 patients with cardiac rhabdomyomas. Of these patients, 20 had been diagnosed during fetal life at a gestational age between 20 and 35 weeks, and 53 postnatally between the ages of 10 days and 11 years.

Number and location of cardiac rhabdomyomas

51 patients (70%) presented with multiple tumours, while the remaining 22 patients had a single tumour. In Table 1, we show the association between the presence of multiple rhabdomyomas and the incidence of tuberous sclerosis. There was no follow up for 4 of the patients, and they are not included in Table 1. Tuberous sclerosis was diagnosed in 42 of the patients (86%) with multiple rhabdomyomas, and in 13 of the patients (65%) with a single tumour ( p value 0.095; Odds Ratio 3.17; confidence interval at 95% of the odds ratio 0.79 to 12.92).

Table 1 Presence of multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas related to the incidence of tuberous sclerosis.

Fisher’s exact test: p value 0.095; Odd’s ratio 3.17; CI at 95% Odd’s ratio 0.79 to 12.92.

The tumours were predominantly located in the left ventricle, with three-quarters of the patients presenting at least one tumour at this site. Almost half of the patients had at least one tumour in the right ventricle, just over two-fifths had a tumour in the ventricular septum, and only a few patients had tumours in the atrial chambers, the atrial septum, or the pericardium.

In Table 2, we show the relation between these different locations and the presence of tuberous sclerosis, in other words the relative risk. The values are given in terms of numbers of patients with and without a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis presenting at least one tumour in the specific locations.

Table 2 Location of the cardiac rhabdomyomas in patients with and without uberous sclerosis.

TS = tuberous sclerosis.

Relative risk = n(TS+)/n(TS−), estimated error for n(TS−) + 1.

Size and evolution of cardiac rhabdomyomas

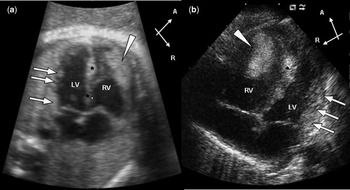

The diameter of the tumours in those diagnosed prenatally ranged from 1 to 37 millimeters, and from 2 to 55 millimeters in those diagnosed after birth. In Figure 1, we show the fetal and postnatal echocardiography of one of the patients. In those diagnosed as positive for tuberous sclerosis, the tumours ranged from 1 to 55 millimeters in size, as opposed to 2 to 30 millimeters for the patients not affected by tuberous sclerosis.

Figure 1 Fetal and postnatal cardiac rhabdomyomas. (a) Fetal echocardiogram at 35 weeks of gestation and (b) transthoracic echocardiogram at 2 weeks of age. The two 4-chamber views show a huge rhabdomyoma in the free wall of the right ventricle (arrowhead) and smaller rhabdomyomas in the ventricular septum (stars) and in the free wall of the left ventricle (arrows). Abbreviations: A: anterior, LV: left ventricle, RV: right ventricle, R: right.

Postnatal regression in both the number and/or size of nodules was observed for 40 of the 54 patients in whom we had follow-up echocardiographic data. Complete resolution of cardiac rhabdomyoma was documented in 28% of the patients, and partial resolution in 46%, with 19% showing no changes in the size of the tumours. In 4 patients, the nodules increased in size, and new masses appeared over 6 to 14 years. Among 15 patients showing complete resolution by 6 months to 10 years of age respectively, 12 had been diagnosed postnatally, and 11 patients had been diagnosed for tuberous sclerosis. In 6 patients, there was partial resolution of big nodules, along with complete resolution of smaller nodules over a time period of 1 to 11 years. In the remaining patients, there was either partial resolution or no changes of the nodules over a time period of 1 to 18 years.

Cardiac complications

Cardiac follow-up by echocardiography performed in 54 patients showed that cardiac complications were encountered in 22%, with 2 patients requiring immediate intervention during the neonatal period. The first patient diagnosed with multiple cardiac rhabdomyoma at 34 weeks of gestational age was delivered by elective Caesarean section at 37 weeks due to significant obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract by one of the nodules, producing a pressure gradient of almost 50 mmHg by Doppler between the aorta and the left ventricle. The nodule was removed surgically in the neonatal period. The second patient diagnosed with multiple cardiac rhabdomyoma at 28 weeks gestational age was delivered uneventfully, but had Wolf-Parkinson-White Syndrome with refractory supraventricular tachycardia for 3 weeks after birth requiring anti-arrhythmic treatment, and is currently stable under therapy. We found evidence of disturbances of rhythm in 7 further patients, 5 in the form of occasional paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia with or without Wolf-Parkinson-White syndrome in infancy. All were stable clinically, and did not warrant any intervention, albeit that one had ventricular arrhythmia. Surgical excision of the tumour was required in 2 patients, one with sub-aortic obstruction and the other with pulmonary obstruction. One patient died at 22 days of age of cardiogenic shock due to obstruction of left ventricular filling caused by a tumour sized at 30 by 30 millimeters. There was no specific dimension or location of the tumours that predicted the disturbances of rhythm.

Neurodevelopmental complications

Tuberous sclerosis was a definite diagnosis in 55 patients (76%), as they fulfilled 2 or more of the major criteria for diagnosis.Reference Roach and Sparagana13 Of these 55 cases, 20% (11) did not have epilepsy whereas 80% (44) did (Fig. 2). Among those with epilepsy, 32 patients had a precise neurological follow up which showed that 2 patients no longer require antiepileptic drugs, having had a long seizure-free interval, 18 patients (56%) are controlled in either good or moderate fashion, having occasional seizures on 1 or 2 antiepileptic drugs, and 12 patients (38%) have refractory epilepsy, still suffering several seizures each week. In 1 patient who had pharmaco-resistent epilepsy in infancy, seizure surgery was performed at 14 months of age, and the patient currently has moderately controlled epilepsy with 2 antiepileptic drugs.

Figure 2 Neurodevelopmental issues in patients with tuberous sclerosis. AED – antiepileptic drugs.

Developmental delay was seen in 36 of the patients (68%) with tuberous sclerosis, the remaining 17 patients developing normally. Findings from follow-up were available for 25 of the patients with developmental delay. Of these, 14 (56%) had mild delay, 8 (32%) had moderate delay, and 3 (12%) had severe delay. In terms of academic performance, 15 (60%) of the developmentally delayed patients are in special schools, 5 (20%) are in regular schools with extra support for academic work, and 5 (20%) are young patients not yet in school. Behavioural problems in the form of reduced attention span, aggressiveness, hyperactivity, impatience and mood fluctuations were encountered in 8 patients (22%) with developmental delay, one of these documented to have autism.

Other findings

A major involvement of other organ systems not in relation to tuberous sclerosis was noted in 2 patients, one having dysmorphism with involvement of multiple organs, and the other having a nephroblastoma requiring removal in infancy.

Discussion

As expected from previous experience,Reference Holley, Martin and Brenner14–Reference Geipel, Krapp, Germer, Becker and Gembruch20 the cardiac rhabdomyomas found in our series of patients were benign. They showed spontaneous regression in most cases, having appeared between 20 and 30 weeks gestational age in any part of the heart. The main growth of the tumours was between the second and the third trimester, as well as during the early postnatal period. During prenatal life, the tumours were, except for one case, clinically silent in our series but intrauterine death has been reported,Reference Takeuchi, Nakayama, Kuwae, Hamana, Inamura and Suehara21, Reference Bader, Chitayat and Kelly22 mostly following fetal arrhythmia and hydrops.

Among the various cardiac complications, arrhythmias were the most often encountered problemsReference Wu, Chen and Hou23–Reference Choi, Jaffe, Maidman and Baxi27 during the neonatal period, with supraventricular tachycardia being the commonest disturbance identified. Bradycardia, heart block, and pre-excitation syndromes have also been reported.Reference Mas, Penny and Menahem28, Reference Van Hare, Phoon, Munkenbeck, Patel, Fink and Silverman29 Arrhythmias were predominantly treatable by vagal maneuver, pharmaco-therapeutic intervention, radio-frequency ablation and/or cardioversion. Only rarely do the arrhythmias cause mortality. Having analyzed the size and location of the tumours in patients with arrhythmia compared to patients without rhythm disturbances, we concluded that there is no specific size or location of the tumour that can predict this particular complication.

Further cardiac complications in our patients included development of obstruction to intracardiac flow, alteration of the function of the atrioventricular valves with consequent regurgitation, cardiac dysfunction, and hydrops. Large left ventricular tumours are known to lead to severe obstruction of the left ventricular outflow tract in some patients, requiring surgical excision.Reference Ikemba, Eidem, Dimas, O’Day and Fraser30, Reference Cabrera Duro, Rodrigo Carbonero and Aramendi Gallardo31 Very rarely, they can produce univentricular physiology in infants, thence posing difficult problems for management.Reference Elderkin and Radford32 The haemodynamic complications encountered in late fetal life can be minimized by well-timed induced delivery or caesarean section. Surgery is only required for severe haemodynamic complications, arrhythmias or other primary cardiac tumours.Reference Sallee, Spector, van Heeckeren and Patel33–Reference Piazza, Chughtai, Toledano, Sampalis, Liao and Morin35

As in our population, the natural history after birth is known to be dominated by the neurological impairment due to tuberous sclerosis.Reference Tworetzky, Mc Elhinney and Margossian8 The importance of the diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis in a patient presenting with cardiac rhabdomyoma is exemplified by our findings concerning neurodevelopmental complications. Of our patients with tuberous sclerosis, four-fifths are affected by epilepsy, and two-thirds suffer developmental delay, findings in accordance with larger demographic series of patients affected by tuberous sclerosis.Reference Aicardi36 Most of the patients with epilepsy, nonetheless, are controlled in good or moderate fashion using antiepileptic drugs, albeit that over one-third have refractory epilepsy. The association with tuberous sclerosis, therefore, is an important issue during the prenatal counselling of parents about the further neurological and psychosocial development of their child.

On the basis of our statistical findings, and in order to enhance the predictions for the parents during the prenatal counseling about the risks of developing tuberous sclerosis, we make several suggestions, well aware that our study, although including a reasonably large number of patients, has all the limitations of a retrospective study.

The presence of multiple cardiac tumours in patients suggests a risk factor of 6 to be affected by tuberous sclerosis. This fact has already been observed in another population,Reference Tworetzky, Mc Elhinney and Margossian8 albeit that these authors found a substantially higher risk factor, of 20. The risk analyses for single cardiac tumours diverge even more. We found a risk factor of 1.9 to be affected by tuberous sclerosis in case of a single tumour, while the other authorsReference Tworetzky, Mc Elhinney and Margossian8 found a factor of 0.33. This divergence could be due to a difference in the two studied populations. We excluded all other primary cardiac tumours than rhabdomyomas, whereas Tworetzky et al.Reference Tworetzky, Mc Elhinney and Margossian8 included other primary tumours in the group of patients presenting with single tumours. It is extremely important, therefore, to differentiate between the primary tumours, such as rhabdomyomas, teratomas, fibromas, and myxomas, during prenatal counseling, since they have a different impact on the neurological outcome related to tuberous sclerosis.

We also observed that the sizes of tumours in patients affected by tuberous sclerosis are slightly bigger. In our population, tumours with a size bigger than 30 millimetres were only observed in patients with tuberous sclerosis. Additional research should be performed to conclude in a more definitive way if the size of the tumours may be a relevant factor in the diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis. By analyzing the incidence of cardiac rhabdomyoma at different location related to the presence of tuberous sclerosis, we can conclude that there is no straightforward relationship between any of the locations and tuberous sclerosis (Table 2). The comparison of the data between our patients diagnosed pre- and postnatally shows in effect no significant difference between the size, the cardiac complications, and the development of tuberous sclerosis.

Tuberous sclerosis is an autosomal dominant Mendelian condition with a large variability of expression and 50% familial occurrence.Reference Chen, Su and Hung37 We only recently embarked on testing our patients genetically, with so far 3 positive outcomes. This should support the opinion that this condition should be suspected in all children with prenatally diagnosed cardiac rhabdomyomas. Genetic testing, therefore, should be used in all patients with these cardiac tumours. Prenatal genetic analysis of the index patient and the parents to exclude polymorphism can also be considered to enable early implementation of further diagnostic evaluation and genetic counselling,Reference Joswiak, Domanska- Pakiela, Kwiatkowski and Kotulska38 although the sensitivity of this technique is not yet elucidated. Recently, prenatal genetic analysis of a fetus with cardiac rhabdomyomas has been performed to confirm the diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis,Reference Milunsky, Shim and Ito39 albeit that precise prenatal molecular diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis has yet to be realized. In the absence of reliable genetic testing, the risk-calculations should be helpful for the prenatal counselling. Genetic testing should particularly be performed for prenatal diagnosis in subsequent pregnancies, if after having had an affected child both parents prove negative for TSC1 and TSC2 mutations on sequencing.

In conclusion, our study approaches a rare problem with a potential cardiac impact perinatally and in early infancy, and long term neurologic sequelae, the importance reflecting the numbers of cases, and not so much in the separation of pre- and postnatal diagnosis. On the basis of this large population, we conclude that cardiac rhabdomyomas generally regress with time, and that surgical and/or pharmacological interventions are rarely required. Arrhythmias exist and may rarely be fatal, but once adequately treated, they play a minor role in the overall outcome. The constant association of cardiac rhabdomyomas with tuberous sclerosis, and the associated neurological impact, in contrast, is the dominating aspect in the long-term outcome and quality of life in these patients. This fact points to the need for prenatal genetic testing, along with comprehensive prenatal counselling of parents whose fetuses are diagnosed with this rare disease.