Introduction

For high-producing dairy cows, energy intake capacity in early lactation is limited, and cannot meet the requirements for milk yield and maintenance (Sundrum, Reference Sundrum2015). Therefore, dairy cows in early lactation usually experience an energy deficit, or negative energy balance (NEB). Cows compensate for this energy deficit by mobilising reserves, which consist mainly of body fat. During intense body fat mobilisation, a large portion of serum non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) is directed to ketone body synthesis in the liver. Thus, the pathophysiological characterisation of ketosis includes high serum concentrations of NEFA and ketone bodies and low concentrations of glucose. The serum ketone bodies are acetone, acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate (BHBA). The ‘gold standard’ test for ketosis is measurement of blood BHBA (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wu, Xu, Xia, Sun and Shu2013).

Milk is a complex mixture of proteins, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, and minerals. Milk fat globule membrane (MFGM) protein is membrane protein packaged around fat globules during the apocrine secretory process. MFGM proteins have been shown to have special value. In addition to reflecting the physiological state of the cows, they act as a source of nutrition and immunity for calves, thus affecting growth, and may regulate immunity and physical fitness in both humans and calves consuming the milk. Interest in the identification and molecular composition of milk proteins has increased in recent years. Using filter-aided sample dimethyl labelling, 169 MFGM proteins have thus far been identified and quantified (Lu et al. Reference Lu, Boeren, de Vries, van Valenberg, Vervoort and Hettinga2011). In the present study, 13 inflammatory proteins were detected by GO analysis.

It has been reported that high concentrations of NEFA, acetoacetate and BHBA in blood are associated with inflammatory states (Esposito et al. Reference Esposito, Irons, Webb and Chapwanya2014; Shi et al. Reference Shi, Li, Deng, Peng, Zhao, Li, Wang, Li and Liu2016; Du et al. Reference Du, Shi, Peng, Zhao, Zhang, Wang, Li, Liu and Li2017), and ketosis has been proven to influence the composition and function of milk (Chatterton et al. Reference Chatterton, Nguyen, Bering and Sangild2013). It is hypothesised that ketosis in postparturient dairy cows may result in changes in MFGM inflammation-related proteins in milk. The specific objective was to determine whether high concentrations of NEFA during ketosis were associated with a reduced likelihood of inflammatory responses in the mammary gland.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the farm owner and all animal experiments were conducted according to the International Guiding Principles for Biomedical Research. The protocol was approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments of the Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University.

Animal grouping and sampling collection

Holstein cows were selected from an intensive cattle farm with 2000 dairy cows in Heilongjiang, China. Our study was conducted during the housing period in January 2016. Cows were housed in stalls, bedded on rubber mattresses, and had free access to drinking water throughout the trial. They were fed a total mixed ration (TMR) at 07:00 and 14:00 daily during the transition period. The 305-d milk yield averaged 9520 kg. Milk and blood samples were collected before feeding at 06:00 on days 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, 23, 26, 29, 32, 35, and 38 after calving. All blood samples were centrifuged to obtain serum at 1000 g for 10 min, then frozen at −20 °C.

A total of 30 Holstein dairy cows, with parity 2 and a mean age of 3·68 years, were selected on the day of calving. The cows were selected based on plasma BHBA concentrations. Cows with a plasma BHBA level of ≥1·40 mol/l were assigned to the ketosis group, and cows with BHBA < 1·40 mol/l and without clinical signs of ketosis were assigned to the control group. These groupings were confirmed using ketone body powder. Initial control samples (C1) were collected from the control group on days 7–14 d after delivery. Later, control samples (C2) were collected on days 14–28. Samples (K1) were gathered on days 7–14 after delivery, before the onset of ketosis in the ketosis group, during ketosis on days 14–28 (K2), and after recovery (K3), when BHBA levels were <1·40 mol/l more than 28 d post-partum.

Fifteen cows were allocated to the ketosis group and twelve to the control group. No inflammatory diseases, such as mastitis, endometritis, displaced abomasum, lameness, or ovarian dysfunction occurred in the cows during the experiment.

Analysis of blood and milk samples

All blood samples were analysed for glucose (GLU), triglyceride (TG), NEFA, and BHBA levels using a fully automatic biochemical analyser, while tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα), blood complement 3 (BC3), and blood complement 9 (BC9) levels were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits from Lengton Bioscience Co. (Shanghai, China).

Milk samples from the Holstein cows were centrifuged for 10 min at 4000 rpm at 4 °C to obtain cream and skimmed milk. The cream (1 ml) was separated, washed with 10 ml 0·9% icy NaCl by vortex mixer, and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C. This washing step was repeated three times (Le et al. Reference Le, Van Camp, Rombaut, van Leeckwyck and Dewettinck2009). The washing solution was removed after centrifugation and frozen at −20 °C. Finally, the washed milk cream was sonicated with PBS (pH 7·2) for 1 min on ice and the protein concentration of the washed cream was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit from Beyotime Biotechnology (Jiangsu, China). The protein concentration was then adjusted to 0·5 g/l for use with the ELISA kits, which were used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Prothrombin (F2), fibronectin (FN1), 5-nucleotidase (NT5E), c4b-binding protein alpha chain (C4BPA), complement C3 (C3), complement C9 (C9), monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 (CD14), and toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) were analysed using ELISA kits from BlueGene Biotech Co. (Shanghai, China), serum amyloid A protein (SAA), alpha-1-acid glycoprotein (ORM1), and alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein (AHSG) were analysed using ELISA kits from Cusabio Biotech Co. (Wuhan, China), inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4 (ITIH4), and complement regulatory protein variant 4(CD46) were analysed using and ELISA kit from EIAab Science Co. (Wuhan, China).

Data analysis

Statistical tests were performed using SPSS 22 computer software (SPSS Statistical Software Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Independent samples t-test and Pearson's correlation coefficient analysis were conducted. The level of significance was established as P < 0·05 and P < 0·01. An enriched network was generated with PCViz (http://PCViz.com) and edited by Cytoscape 3.5.1 (http://www.cytoscape.org/).

Results

Blood biochemical parameters

Table 1 displays the results of biochemical markers, and shows that indicators of energy balance and inflammation in plasma were significantly different between the groups and in line with the literature. In comparisons between the various groups, BHBA was found to be significantly higher (P < 0·05) in K2 than in K1; GLU was significantly higher (P < 0·05) in K3 than in K1; NEFA and BHBA were significantly lower (P < 0·05) in K3 than in K2; NEFA and BHBA were significantly higher (P < 0·05), and C9 significantly lower (P < 0·05), in K1 than in C1; NEFA and BHBA were significantly higher (P < 0·05), and C3 and TNFα significantly lower (P < 0·05), in K2 than in C2; BHBA was significantly higher (P < 0·05) in K2 than in K1.

Table 1. Blood biochemical markers in control and ketotic cows

TG, triglyceride; NEFA, non-esterified fatty acid; BHBA, β hydroxybutyric acid; GLU, glucose; BC3, blood complement C3; BC9, blood complement C9.

Values are means ± se. Within rows, values sharing the same superscript are significantly different at P < 0·01 (A:F) or P < 0·05 (a:f). 2 tailed analysis.

Changes in inflammation-related MFGM proteins in ketotic cows

Table 2 shows the results for inflammation-related proteins in MFGM proteins, changes in which were associated with the onset of ketosis. Comparisons between groups revealed the following: C4BPA, F2, C3, and ORM1 were significantly higher (P < 0·05), and CD14 significantly lower (P < 0·05) in C2 than in K2; ITIH4, C9, F2, AHSG, and CD46 were significantly higher (P < 0·05), and CD14 and CD46 significantly lower (P < 0·05) in K2 than in K1; ITIH4, F2, and ORM1 were significantly higher (P < 0·05), and CD14 significantly lower (P < 0·05) in K3 than in K1; ITIH4, C4BPA, C3, and CD46 were significantly higher (P < 0·05), and F2, AHSG, and ORM1 significantly lower (P < 0·05) in K1 than in C1; CD14 and ORM1 were significantly lower (P < 0·05) in K2 than in C2; SAA and ORM1 were significantly lower (P < 0·05) in K3 than in K2.

Table 2. Inflammation-related proteins in milk fat globule membrane protein from control and ketotic cows.

F2, prothrombin; FN1, fibronectin; NT5E, 5-nucleotidase; C4BPA, C4b-binding protein alpha chain; C3, complement C3; C9, complement C9; CD14, monocyte differentiation antigen CD14; TLR2, toll-like receptor 2; SAA, serum amyloid A protein; ORM1, alpha-1-acid glycoprotein; AHSG, alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein; ITIH4, inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4; CD46, complement regulatory protein variant 4.

Values are means ± se. Within rows, values sharing the same superscript are significantly different at P < 0·01 (A:F) or P < 0·05 (a:f). 2 tailed analysis.

Pearson correlation analysis of inflammation-related MFGM proteins and haematological indexes

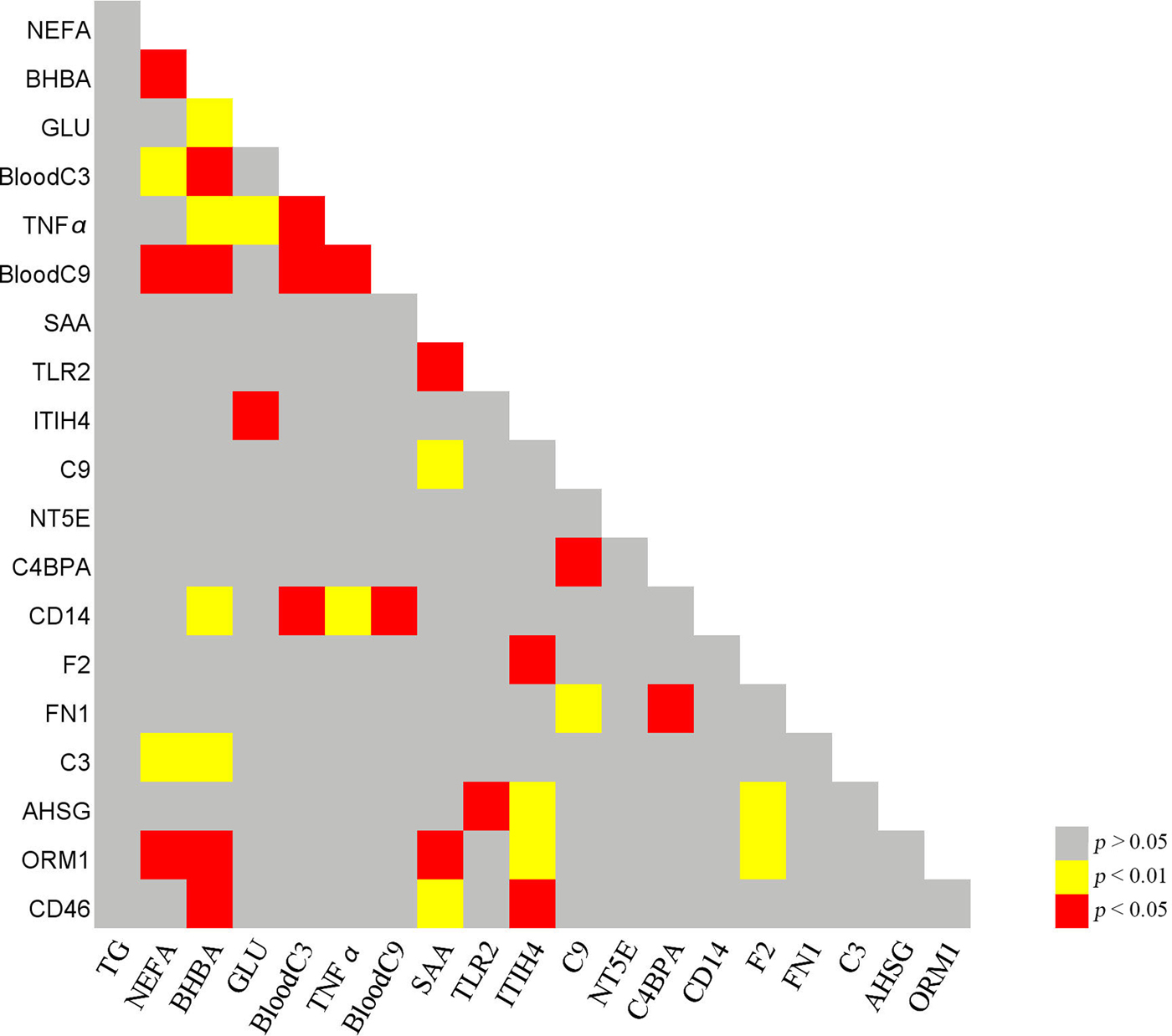

Figure 1 shows the results of correlation analysis of inflammation-related proteins and haematological indexes. It is worth noting that the concentration of NEFA was significantly correlated with BHBA, BC3, BC9, C3, and ORM1 levels. The concentration of BHBA was significantly correlated with BC3, TNFα, BC9, CD14, C3, and ORM1 levels, while GLU concentration was significantly correlated with TNFα and ITIH4 levels.

Fig. 1. Correlative analysis of inflammation-related proteins and haematological indexes. TG, triglyceride; NEFA, non-esterified fatty Acid; BHBA, β hydroxybutyric acid; GLU, glucose; BC3, blood complement C3; BC9, blood complement C9; F2, prothrombin; FN1, fibronectin; NT5E, 5-nucleotidase; C4BPA, C4b-binding protein alpha chain; C3, complement C3; C9, complement C9; CD14, monocyte differentiation antigen CD14; TLR2, toll-like receptor 2; SAA, serum amyloid A protein; ORM1, alpha-1-acid glycoprotein; AHSG, alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein; ITIH4, inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H4; CD46, complement regulatory protein variant 4. P < 0·01 red; P < 0·05, yellow; P > 0·05, grey.

Discussion

The systemic immune response stimulated by non-esterified fatty acids

Serum concentrations of NEFA and BHBA are well accepted as indicators of energy balance in dairy cows. In this experiment, we found BHBA and NEFA levels to correlate with those of inflammatory biomarkers in blood. During NEB, serum levels of NEFA and BHBA increase, a change that has been associated with a high incidence of disease or impaired reproductive performance (Ospina et al. Reference Ospina, Nydam, Stokol and Overton2010) .

Previous studies have shown that high yielding, clinically healthy cows also have inflammatory responses in the liver and uterus during the transition period and early lactation, although the exact mechanisms behind these effects are not completely understood. There are several hypotheses regarding this inflammatory response, including the elevated levels of circulating NEFA (Lu et al. Reference Lu, Antunes Fernandes, Paez Cano, Vinitwatanakhun, Boeren, van Hooijdonk, van Knegsel, Vervoort and Hettinga2013). The first hypothesis concerns a change in the fatty acid (FA) composition of milk and blood in the periparturient cow. The increased energy requirement at the onset of lactation in cows is associated with mobilisation of body reserves. As a result of extended lipolysis of adipose tissue, there is a partitioning of NEFA into the bloodstream. In cows, the presence of unesterified FA has been related to inflammatory diseases such as mastitis and metritis (Sordillo et al. Reference Sordillo, Contreras and Aitken2009). In humans, an increased level of circulating NEFA in blood is also associated with increased systemic inflammatory conditions (Wood et al. Reference Wood, Scott, Garg and Gibson2009). Furthermore, high concentrations of NEFA and acetoacetate can induce an inflammatory response in bovine hepatocytes through activation of the oxidative stress-mediated NF-kB signalling pathway (Shi et al. Reference Shi, Li, Deng, Li, Sun, Yuan, Song, Wang, Li and Li2015; Li et al. Reference Li, Ding, Wang, Liu, Huang, Zhang, Guo, Wang, Li, Liu, Wu and Li2016; Song et al. Reference Song, Li, Gu, Fu, Peng, Zhao, Zhang, Li, Wang, Li and Liu2016).

It has been shown that NEFA utilise TLR4 receptors to induce a proinflammatory response in adipocytes, macrophages, and the liver (Wood et al. Reference Wood, Scott, Garg and Gibson2009). Some NEFA are direct precursors of various bioactive eicosanoids, such as prostaglandin (PG) E2, which possess immunomodulatory functions. NEFA are also being recognised for their role as second messengers or regulators of signal transduction or transcription factors. Exposure of various cell types to saturated free fatty acids has been shown to activate the inflammatory regulator NFκB, resulting in the release of various proinflammatory mediators, such as TNFα, IL-6, IL-8, and IP-10 (Wood et al. Reference Wood, Scott, Garg and Gibson2009; Sun et al. Reference Sun, Yuan, Chen, Wang, Wang, Sun, Li, Li and Liu2017). Based on the theory above, and the results of this experiment, a possible mechanism by which NEFA may trigger an inflammatory response and induce cytokine production in mammary epithelial cells is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Modes by which NEFA trigger inflammatory responses and induce cytokine production in mammary epithelial cells. NEFA utilise TLR4 receptors to activate the inflammatory regulator NFκB, resulting in changes to the cytokines and acute-phase proteins on milk fat globules. The symbols + and − indicate an increase (+) or decrease (−) in biomolecule levels. NEFA, non-esterified fatty acid; TNFα, tumour necrosis factor α; MFG, milk fat globule; nAPP and pAPP, negative and positive acute-phase proteins.

Acute-phase response during negative energy balance

The periparturient period of dairy cows is associated with a compromised immune system (Mallard et al. Reference Mallard, Dekkers, Ireland, Leslie, Sharif, Vankampen, Wagter and Wilkie1998). This can be related to major metabolic demands imposed by the start of lactation, which results in NEB and an increased risk of metabolic disorders. Several studies have shown that NEB and associated metabolic disorders, such as fatty liver and ketosis, are accompanied by decreased lymphocyte function (Suriyasathaporn et al. Reference Suriyasathaporn, Daemen, Noordhuizen-Stassen, Dieleman, Nielen and Schukken1999), phagocytosis (Zerbe et al. Reference Zerbe, Schneider, Leibold, Wensing, Kruip and Schuberth2000), plasma concentration of antibodies (Van Knegsel et al. Reference Van Knegsel, de Vries Reilingh, Meulenberg, Van den Brand, Dijkstra, Kemp and Parmentier2007) and antibody responses (Wentink et al. Reference Wentink, Rutten, Van den Ingh, Hoek, Müller and Wensing1997). Inflammation-related proteins may play an important role in these phenomena. In order to assess the possible roles of inflammation-related MFGM proteins, we employed the PCViz network visualisation tool (http://www.pathwaycommons.org) to construct a gene interaction network based on information mined from published literature. This network was used to analyse the possible gene interactions for F2, FN1, AHSG, SAA, NT5E, C4BPA, C3, C9, ITIH4, CD46, CD14, TLR2, and ORM1 (Fig. 3). We found that there were no identified gene interactions for ORM1, while FN1, AHSG, SAA, NT5E, C4BPA, C3, C9, ITIH4, CD46, CD14, and TLR2 play critical roles in the acute-phase response.

Fig. 3. The gene interaction network of F2, FN1, AHSG, SAA, NT5E, C4BPA, C3, C9, ITIH4, CD46, CD14, TLR2, and ORM1. We identified no gene interactions for ORM1 because of lack of research, while F2, FN1, AHSG, SAA, NT5E, C4BPA, C3, C9, ITIH4, CD46, CD14, and TLR2 play critical roles in the acute-phase response. Those increasing in ketotic cows are drawn within the positive triangle frame, and those reducing were drawn within the v-type frame. The enriched network was constructed using the Pathway Commons Network Visualizer (PCViz) web tool http://www.pathwaycommons.org and edited with Cytoscape 3.5.1 (http://www.cytoscape.org/).

A second hypothesis concerns the stress associated with the rapid increase in milk production in periparturient dairy cows, and suggests that this may explain the acute-phase response in NEB. In mammary epithelial cells, the onset of milk production requires the highly efficient transport, synthesis, and secretion of milk components, challenging the homeostasis of the mammary gland. This can result in an acute stress response that stimulates transient adaptation when other homeostatic mechanisms (e.g. mammary gland epithelial cell proliferation and differentiation) cannot cope with this high demand for milk production (Medzhitov, Reference Medzhitov2008). It is also known that physiological stress and damage or malfunction of tissue can induce an inflammatory response. Thus, these physiological processes taking place in periparturient cows may explain why acute-phase proteins are present at higher concentrations in early-lactation cows in ketosis. Both hypotheses identify the secretion of a number of acute-phase proteins (APPs) in response to inflammation at the onset of ketosis.

ITIH4 is a type II APP involved in inflammatory responses to trauma, and may also play a role in the development or regeneration of the liver (Pineiro et al. Reference Pineiro, Andres, Iturralde, Carmona, Hirvonen, Pyörälä, Heegaard, Tjørnehøj, Lampreave and Pineiro2004). CD14 is a coreceptor for bacterial lipopolysaccharide, and acts via MyD88, TIRAP, and TRAF6, leading to NFκB activation, cytokine secretion, and an inflammatory response (Wright et al. Reference Wright, Ramos, Tobias, Ulevitch and Mathison1990). ORM1 is a lipocalin (Lögdberg & Wester, Reference Lögdberg and Wester2000) with immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory activity, and plays an important role in the regulation of local inflammatory reactions (Tilg et al. Reference Tilg, Vannier, Vachino, Dinarello and Mier1993), including those due to excessive apoptosis (Van Molle et al. Reference Van Molle, Libert, Fiers and Brouckaert1997). Identical orosomucoid 1 somatic cell isoforms can be found in both milk and blood PMN cells (Ceciliani et al. Reference Ceciliani, Pocacqua, Lecchi, Fortin, Rebucci, Avallone, Bronzo, Cheli and Sartorelli2007). Mammary gland epithelium expresses ORM1 (Ceciliani et al. Reference Ceciliani, Pocacqua, Provasi, Comunian, Bertolini, Bronzo, Moroni and Sartorelli2005) and other acute-phase proteins, including haptoglobin, M-SAA3, and albumin (Rainard & Riollet, Reference Rainard and Riollet2006). In addition, SAA is a major acute-phase reactant and has been demonstrated to mediate proinflammatory cellular responses (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Yoo, Cho, Suh, Kim and Ryu2006).

The APPs are characterised by a nonspecific rapid response to stimuli such as inflammation (infections, autoimmune diseases, etc.) or tissue damage (trauma, surgery, myocardial infarction, or tumors). The acute-phase response is considered to be a dynamic process, involving systemic and metabolic changes, which may provide an early nonspecific defence mechanism against an insult before specific immunity is achieved (Petersen et al. Reference Petersen, Nielsen and Heegaard2004). Some proteins (e.g., C3 and FN1) increase during an acute-phase reaction and are known as positive APPs, while others (e.g., ORM1 and AHSG) decrease and are known as negative APPs.

Conclusions

The hypothesis that ketosis in postparturient dairy cows results in changes in MFGM inflammation-related proteins in milk was clearly confirmed by our study. This study shows that the MFGM proteins related to acute inflammatory and immune responses (C3, F2, ORM1, ITIH4, AHSG, C9, and CD46) are drastically different in healthy and ketotic cows. Due to the specific origin of MFGM, this could imply that these acute-phase proteins are present in higher concentrations in or on mammary epithelial cells of cows in NEB during early lactation. The concentrations of C3, C9, and TNFα in blood, and of C3, CD14, and ORM1 in MFGM proteins are correlated to energy balance. Increases in ITIH4 and CD46, and decreases in AHSG and ORM1 observed before the onset of ketosis may be useful indicators to identify and monitor cows at risk of ketosis. Further studies with larger cohorts of animals are warranted to validate the identified biomarkers.

The authors are grateful for financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No. 31672622) and National Program on Key Research Project of China (2016YFD0501206).