Introduction

Territorial integrity is a central element of the Westphalian state system of sovereign states, of modern states’ self-understanding and international law documents such as the UN Charter. It is also pivotal to preserving peace among clearly bordered states. Most contemporary states in Europe, but also elsewhere, understand themselves as nation states. This includes the strive for homogeneity of the ethnoculturally defined titular nation. Usually, these processes end with this nation being defined exclusively as essence of the state’s history, culture, language, values, norms, and even natural environment. Obvious disturbances of this perception of national-cultural homogeneity, especially in peripheral areas of the state, have led to the development of the concept of national minority. This concept containerizes ethnic diversity into different, but internally ethno-cultural homogeneous sub-groups, the national minorities. While aiming to solve the dilemma of ethno-cultural diversity in most, if not all European states, the existence and acceptance of national minorities continues to challenge the idea of nation states’ national homogeneity and territorial integrity.

Defining the nation as the fundamental element of a state creates an incitement for national minorities to perceive themselves as sub-state nations striving to achieve a state of their own. In consequence, national minorities become an implicit threat to territorial integrity – especially if sponsored by a kin-state with historic or contemporary territorial expansionism. This complicates the territorial notion of minorities, not the least because many contemporary national minorities, as understood by the European Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (FCPNM), are the result of controversial post-imperial border drawings after World War I and, more recently, after the end of the Cold War, when new states were established and Europe’s borders were rearranged.

Non-territorial autonomy (NTA) is a concept to ensure political and cultural participation of national minorities in society and thus a tool to manage diversity without challenging territorial integrity. I will argue here that the concept of autochthonous national minorities, a result of the triumphal procession of the nation state in nineteenth and twentieth-century Europe, poses different challenges to manage diversity in contemporary Europe and requires a rethinking of non-territorial autonomy. The concept of national minorities as well as NTA suggest a primordialist nationalism studies’ approach of an ethnonational stability; a historical and territorial continuity of nations from ancient times (Smith Reference Smith1987; and, more recently, Gat Reference Gat2013). They neglect social constructivist approaches to nationalism and other categories of analysis of borderland populations as national and transnational borderlanders (Martinez Reference Martinez1994) or regionauts (O’Dell Reference O’Dell2003; Löfgren Reference Löfgren2008). Therefore, this article is asking the research question of whether NTA really can operate in a societal system, disconnected from territory.

It will add a border studies viewpoint on NTA by including the continuous impact of historic processes of bordering and de-bordering on the management of diversity. Bordering is here understood not only as a territorial demarcation of two states but also as a process of social demarcation of people inhabiting space (Houtum, Kramsch, and Zierhofer Reference Houtum, Kramsch and Zierhofer2005) into distinguishable communities – here understood as ethnoculturally defined nations and national minorities, alongside binary, exclusive forms of either-or identities. How important are images of ethnoterritorial and ethnocultural stability for NTA, and how do they influence the negotiation of the management of national and cultural diversity? Focus point is cultural autonomy in a bordered societal system, understood as a state uniting different ethnocultural groups but clearly demarcating them from each other – e.g., in the institutionalizing of NTA, requiring exclusive identification and neglecting forms of multiple ethnocultural identification and/or ethnonational indifference (Zahra Reference Zahra2010; Judson and Rozenblit Reference Judson and Rozenblit2005).

Choice of Case, Theoretical Framework, and Method

I will use the explanatory case study of the Danish minority in South Schleswig to demonstrate the inherent territoriality of the concept of national minority as well as the dilemmas inherent in applying this concept. The former duchy of Schleswig is an interesting case of a border region, where historic processes have led to a division of an economically and socially integrated region. This division incurred after a long nineteenth century of national awakening, national conflict, and power politics, combined with elements of national assimilation policies and eventually national self-determination. After the division of the region in 1920, the dissenters were offered national minority status based on self-identification, along with cultural self-administration. This has resulted in the institutionalization of a German minority in Danish North Schleswig and a Danish minority in German South Schleswig, with separate schools, church congregations, and cultural associations, effectively making it possible to live as a Dane in South Schleswig and as a German in North Schleswig from cradle to grave.

NTA is deeply imbedded into the study of nationalism and nationalization processes. The historiography of nationalism usually differentiates between the primordialist approach on the ethnic origin of nations (Smith Reference Smith1987; Gat Reference Gat2013), social constructivist approaches on imagined communities (Anderson Reference Anderson1983), and especially constructed or even invented nations (Hobsbawm and Ranger Reference Hobsbawm and Ranger1983). In the latter, elites mobilize populations with some joined ethnocultural characteristics, especially language, into eventually, ideally, forming homogeneous nations (Hroch Reference Hroch2005). The process of nationalization often aligned with democratization – democracy craving the formation of a demos as universally accepted group of people to rule with clear demarcation of who belongs to the demos and who does not. It also coincided with the disintegration of European empires. While predominant for the self-understanding of contemporary European states, nationalization was never complete: national indifference has existed widely (Zahra Reference Zahra2010), but also what we understand as national minorities reflect the ambivalence of aligning ethnicity, nationality, and state in nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first-century Europe.

The concepts of national minority and NTA are in-built in the concept of the nation as a homogeneous, primordial, stable community. The dilemma of imperfect geographical borders, cultural border zones, and ethnic diversity within set geographical spaces, on the one hand, and the aim to delineate homogeneous nation states, on the other hand, should be solved by consolidating diversity into national minorities and NTA. The reality of multicultural societies and conglomerate empires of the nineteenth century consisting of territories accumulated mostly by dynastic processes was confronted with a new form of b/ordering space (Houtum, Kramsch, and Zierhofer Reference Houtum, Kramsch and Zierhofer2005). Democratization and nationalization resulted in more or less successful alignments of the map of Europe to civil, ethnic, and democratic nation states. Here, the concept of national minority as a clearly bounded, stable, endemically reproduced community was invented and paternalistically applied in twentieth-century re-borderings of the map of Europe, most prominently in the post-World War I peace order.

Non-territorial autonomy (NTA) covers arrangements where members of ethno-cultural minorities have been granted national cultural autonomy, functional cultural autonomy, or simply cultural autonomy as individuals – functional autonomy as a cluster of regulations and deregulations ensuring self-governance of minority institutions being the most common (Malloy Reference Malloy, Malloy and Salat2021, 3). NTA thus could be characterized as a form of political decentralization, with minority institutions coexisting with state institutions with similar functions (Malloy Reference Malloy, Malloy and Salat2021, 5). It has been hailed as a good model for accommodation of ethnonational groups that cannot claim rights to a territorial homeland (Malloy Reference Malloy, Malloy and Salat2021, 3). Central to NTA is the focus on individuals enjoying cultural rights – not on groups or territories (ibid.). Nevertheless, these rights are administered by institutions of the group (ibid.), which does not eliminate the notion of minorities as stable, institutionalized groups with a defined membership. NTA is, as such, a static concept: it shall guarantee cultural, linguist, and sometimes religious autonomy of a historic ethnocultural group diverging from the titular nation of the state and thereby preserving this group and its apparent difference.

Despite its origins as a non-territorial concept attempting to manage diversity within the conglomerate Habsburg empire, I argue that it has become inherently territorial in its actual application and implementation. This is mainly because of the concept of autochthonous national minorities being territorial: autochthony refers to the minority’s ties to a territory, and the concept refers to ethnocultural groups residing within a territorially demarcated state. It becomes a dilemma that NTA, rightly evading the establishment of territorial autonomy by guaranteeing cultural autonomy, nevertheless is supposed to institutionalize an autochthonous minority culture, which, with the possible exception of dispersed and historically nomadic minorities such as the European Sinti and Roma, has references to a territory of residence.

The Strukturdebat (debate on the structure of minority self-governance) within the Danish minority in South Schleswig is here used as an example to demonstrate the challenges of a socially integrated minority, as it demands societal bordering, a clear narrative of “us” and “them” to define political rights, and, finally, a notion of territory based on the minority’s historical self-understanding. The case study is based on my own and others’ research on the Schleswig case and observation of recent developments within the triad of minority self-understanding, kin-state policies, and the relations between the minority and its state of residence and citizenship. I will use the discourses within the Danish minority of South Schleswig, as reflected in the minority’s daily newspaper Flensborg Avis as a source for the strukturdebat on the perceived democratic deficits, the lack of efficiency of the current structure of minority self-governance, and the models discussed to overcome these issues. This article will critically reflect on the implementation of NTA in Schleswig and the underlying concept of a national minority as an identifiable, bordered parallel society and the complications this concept implies for implementation of NTA.

The Schleswig-Case: A European Model?

The Schleswig region (geographically understood as the former duchy of Schleswig) is widely perceived as a model of successful border-delineation based on national self-determination and subsequent reconciliation and accommodation of national, linguistic, and cultural binarity in a majority-minority framework with wide-ranging cultural autonomy and respect for active kin-state involvement in culture and education (Klatt Reference Klatt2015; Kühl and Weller Reference Kühl and Weller2005; Kühl Reference Kühl2005b; Kühl and Bohn Reference Kühl and Bohn2005); but also acknowledging deficits in the deep implementation of the model and its susceptibility to crisis (Klatt Reference Klatt2014; Kühl Reference Kühl2012; Hughes, Megoran, and Benwell Reference Hughes, Megoran and Benwell2020). The region was divided between Denmark and Germany in 1920 after national mobilization and conflict, two wars, and national assimilation policies in the long nineteenth century. A plebiscite was implemented to confirm a nationally optimal border drawn along a line previously decided upon by Danish experts and politicians (Fink Reference Fink1979, Reference Fink1995). The dissenters of the plebiscite (the 25 percent who had voted for Germany in North Schleswig and the 20 percent who had voted for Denmark in South Schleswig) were accommodated as – or rather mobilized and assimilated into – national minorities, based on subjective self-identification. Both minorities have since provided their members a parallel institutional framework governing their cultural, religious, and linguistic affairs, as supported by the respective kin-state (Kühl Reference Kühl, Kühl, Bohn, Danker, Pohl and Ruck2005a).

History: from Conglomerate to Nation State

The Schleswig settlement of minority accommodation reflects a historic conflict on the duchy’s belonging, when competing Danish and German national movements arose in the nineteenth century (among others, Henningsen Reference Henningsen2011; Klatt Reference Klatt, de Boer, Petersen, Spierings and van der Velde2020; Thaler Reference Thaler2009; Berdichevsky Reference Berdichevsky1999). Administratively, it had been tied to Holstein since the fourteenth century, despite being a royal Danish fief, while Holstein was a fief of the Holy Roman Empire. A Schleswig-Holstein movement, representing the German-speaking elites, was challenged by a national Danish movement attempting to strengthen the role of the Danish language and later also integration into a Danish nation state. While language was a major issue, loyalty to the monarchy was felt strongly by most inhabitants. Economic reasons also played a role in identification, but national indifference (Zahra Reference Zahra2010) was widespread, too. In a typical Hrochian way (Hroch Reference Hroch2005), nationalist elites mostly from the Copenhagen bourgeoisie and German universities mobilized at least the property-owning part of the population from the 1840s. Two wars were fought on Schleswig (1848–1851 and 1864), the latter ending with the duchies’ integration into the Prussian state and, from the 1880s, harsh policies of national and cultural assimilation of the Danish-oriented population.

With Germany’s defeat in World War I, Schleswig came onto the agenda of the Paris Peace Conference. Denmark proposed a decision based on the Right of National Self-Determination. Two plebiscites were held in February (zone 1, North Schleswig) and March 1920 (zone 2, Central Schleswig including Flensburg), resulting in today’s border (Fink Reference Fink1979). In fact, 75 percent in the northern plebiscite zone had voted for Denmark and 80 percent in zone 2 had voted for Germany. These results were rather clear decisions, but they also demonstrated the difficulty to find the perfect national border. Both Denmark and Germany pledged to accommodate the dissenters of the plebiscites by guaranteeing national minority rights and cultural autonomy. This was basically implemented in the early 1920s, following three principles, which still are considered the foundation of the Schleswig minority model today (Noack Reference Noack1989; Becker-Christensen Reference Becker-Christensen1990):

-

1. Subjective, personal decision on minority membership

-

2. Self-administered cultural institutions, including schools

-

3. State of residence tolerates co-financing of these institutions by the kin-state

Territoriality was implied in this autonomy, as minority institutions were limited to the territory of the former duchy of Schleswig.

The principle of subjective decision on minority membership has been the most challenging with regard to NTA, but also daily practice of minority living. The idea of national identity as a core element of individual identification and self-perception has become deeply ingrained in at least Western concepts of identity and state building. Neither in 1848 nor in 1920 or today has nationality been a stable, continuous characteristic of the inhabitants of Schleswig. Often crisis resulted in partly dramatic changes of identification (Klatt Reference Klatt2019). This became very explicit when the national balance turned around after the surrender of Nazi-Germany in 1945. While the German minority in North Schleswig suffered decline, a majority of the native population of South Schleswig agitated for a “reunification” with Denmark (Noack Reference Noack1991). This movement mobilized considerable political and civil society support in Denmark but failed to change the different Danish governments’ reluctant approach to this sensitive issue (Noack Reference Noack1991). Eventually, not the least because of the outbreak of the Cold War and the foundation of the West-German federal republic, the situation was pacified by the Bonn-Copenhagen minority declarations in 1955 – parallel government declarations acknowledging the existence of minorities and confirming the principles of subjective self-identification, cultural autonomy, and the entitlement to kin-state support (Noack Reference Noack1997; Kühl and Weller Reference Kühl and Weller2005).

The Schleswig Model – Non-Territorial Autonomy?

It can be argued that NTA is not the concept most suitable to describe the Schleswig minority regime, as the minorities in Schleswig do not have genuinely separate political, juridical, or administrative institutions that would live up to the original expectations developed by Karl Renner and other early proponents of NTA. The Schleswig minorities have organized their minority life through private associations with specific cultural and social purposes. While private schools with a distinctive pedagogical or cultural-linguistic concept exist in most Western societies, the self-understanding of the private Danish and German minority schools in Schleswig is that they do not provide an alternative to the public school system but are inherently tailored for the minority members’ children. The minorities themselves reiterate that they consider the schools to be the minorities’ public schools. This status has been confirmed in the school law of the German state of Schleswig-Holstein. I will therefore argue that the Schleswig minority regime was constructed and has been lived in the spirit of NTA by guaranteeing the minorities cultural, linguistic, and educational self-administration, no matter the organizational form.

The Danish minority of South Schleswig operates within such a framework of functional cultural autonomy. It is one of the four minorities Germany has recognized under the FCPNM. Furthermore, the constitution of the federal state of Schleswig-Holstein of 1990 (article 5) confirms the minority’s cultural autonomy (kulturelle Eigenständigkeit) under the state’s and its municipalities’ protection. It also confirms the principle of subjective self-identification, clearly repudiating objective criteria as linguistic abilities (Harck Reference Harck2005). In practice, cultural autonomy is performed through several functional, member-based private associations following German law for charitable, non-profit associations (Vereinsrecht). Its daily newspaper Flensborg Avis and its bank Union Bank are public stock companies though. The only coordinating institution is Det sydslesvigske samråd, a South Schleswig Joint Council, to coordinate and also to function as a sort of minority presidency in relations with Danish and German politicians. Chairmanship in the Samråd is rotating. Decisions can only be made unanimously.

Members of the Joint Council are

-

• The Danish library (Dansk Centralbibliotek for Sydslesvig), with a main library in Flensburg and branches in Husum and Schleswig. Independent, but sharing resources with Denmark’s system of public libraries

-

• The Danish Lutheran Church (Dansk Kirke i Sydslesvig), organizationally a part of the Danish People’s Church Abroad ( Dansk kirke i udlandet). Eighteen parishes in South Schleswig. No religious organization for the negligible number of minority members belonging to other faiths

-

• Danish School Association (Dansk Skoleforening for Sydslesvig), the largest association in budget and membership, responsible for schools and kindergartens. Obligatory membership for all parents of school and kindergarten children

-

• Danish Health Services (Dansk Sundhedstjeneste for Sydslesvig). Supplementary to the German public health services, operates nursing homes, homecare, health support for children and families

-

• The Frisian Association (Friisk Forening). This association represents the Frisians who perceive themselves as a national minority.Footnote 1 Supports cultural activities

-

• South Schleswig Youth Associations (Sydslesvigs danske Ungdomsforeninger), operates after school childcare, youth activities, summer camps, umbrella organization for minority sports clubs

-

• South Schleswig Association (Sydslesvigsk Forening, SSF), the cultural association of the minority. Membership in SSF is considered a must if you identify with the minority. Local districts all over South Schleswig, bearer of cultural identity, organizes cultural events and cultural exchange with Denmark, usually representing the minority in issues related to the Council of Europe and its conventions

-

• “The affiliated associations” (“De Tilsluttede Foreninger”), representing other small minority associations covering different aspects of minority life (e.g., an agricultural association, a historical association, a business association)

-

• South Schleswig Voters’ Association (Südschleswigscher Wählerverband, SSW). The minority’s political party is represented in the German national parliament, Bundestag, in the Schleswig-Holstein State Parliament, in the four county councils of South Schleswig and in 68 municipal councils (March 2022). At EU-level, it is a member of the European Free Alliance, a group of regional and minority parties

-

• The Danish Border Association(Grænseforeningen) has observer status. This NGO is channeling Danish funds to the minority institutions and provides people-to-people kin-state support

These associations operate minority institutions, parallel to public institutions. Enrollment is voluntary except for the school association, where parents become members when enrolling their child in a minority daycare, kindergarten, or school. The minority daycares, kindergartens, and schools operate as private institutions and follow the respective laws of the state of Schleswig-Holstein. Staff is recruited from within the minority and from Denmark, with a clear policy to have Danish majority teaching staff to ensure cultural transfer from the kin-state.

This construction of minority self-governance facilitates clear accountability and democratic involvement of the association members but does not establish a joint membership of the Danish minority of South Schleswig by itself, as a demos to base a democratically legitimate minority self-government – and it is this issue that focuses strongly in debates on how to improve and restructure the minority’s self-government. All associations are in principle autonomous within their field of work, and they have independent budgets funded by Danish and German public means as well as (low) membership fees. Institutions and associations restrict their activities to the territory of the former duchy of South Schleswig with an imaginative borderline (it does not follow contemporary administrative boundaries) following the Kiel Canal from Kiel to Rendsburg, hereafter the Eider river to its mouth south of Tönning.

Thus, in principle, minority identification and placement of institutions is territorially restricted to South Schleswig. This leads to the rather absurd situation where the northwestern boroughs of the city of Kiel are legitimate places to operate Danish institutions, while most of the city is not. In practice, school attendance is not restricted to South Schleswig though, as children residing south of this line are accepted, including the organization of school busing within the whole city of Kiel. The minorities’ political party SSW has loosened its strict adherence to limit activities to geographical South Schleswig too. In 2000, a new voting law made it possible to casts ballots on the SSW everywhere in Schleswig-Holstein, even though the party only nominated candidates in South Schleswig. There is now a party group (though not formalized as official party district) for SSW members residing in Holstein and Hamburg. In 2012, the party explicitly redesigned its regional approach from South Schleswig to cover all of Schleswig-Holstein (Klatt and Kühl Reference Klatt and Kühl2015). Since 2000, the SSW has received about half of their nominal votes outside South Schleswig. There is little evidence though of whether these voters were minority members or what their motivation was in voting for the Danish minority party (Klatt and Kühl Reference Klatt and Kühl2015).

Mobile Minorities

The minority’s institution’s territorial restriction to South Schleswig was challenged by breaking news on March 26, 2015, when the Danish minority newspaper Flensborg Avis, together with other Danish newspapers, reported that the Danish minority had doubled in size. Instead of the commonly accepted assessment of 50,000 minority members (for the methods of assessment, see Kühl Reference Kühl, Kühl, Bohn, Danker, Pohl and Ruck2005c), a study based on a representative telephone survey had assessed the minority to number 104,000, with a 95 percent confidence interval ranging from 75,000 to 134,000 (Schaefer-Rolffs and Knapp Reference Schaefer-Rolffs and Knapp2015, 5). The immediate surprise was clarified easily: Schaefer-Rolffs’ and Knapp’s telephone survey covered not just historic South Schleswig but the full federal state of Schleswig-Holstein and the city of Hamburg, which has federal state status in Germany. The study has a methodological weakness, as only 95 of the 2,500 interviewed identified with the minority (ibid., 7). Nevertheless, the study estimates about 42,000 minority members residing in South Schleswig, about 37,000 in Holstein (predominantly in the state capital Kiel and counties belonging to the Hamburg metropolitan region), and about 25,000 in Hamburg.

Furthermore, the study provides interesting facts about the geographic and intercommunity mobility of minority members. The first is not surprising regarding the fact that South Schleswig is a peripheral region of Germany with few opportunities for higher education and a rather narrow labor market. Historically, out-migration had played a role in the late nineteenth century (Nielsen Reference Nielsen1994); it had been a threat to a stable Danish minority in the interwar years when many young minority members migrated to Denmark after graduating from school to find work (Thomsen Reference Thomsen2020) as well as from the German economic recovery in the 1950s (Henningsen, Klatt, and Kühl Reference Henningsen, Klatt and Kühl1998; Henningsen Reference Henningsen2009). For the latter, intercommunity mobility is demonstrated by two-thirds of the interviewed residing in Schleswig-Holstein and all residing in Hamburg claiming to be the only minority member in their household (Schaefer-Rolffs and Knapp Reference Schaefer-Rolffs and Knapp2015, 7).

A more controversial aspect of intercommunity mobility is the issue of “recruitment” of apparently German families into the minority. This discourse has often focused on perceived material reasons for people to join the minority associations and institutions, as minority affiliation is a subjective decision not based on any objective, measurable criteria. It was especially outspoken in times of German crisis such as the loss of World War I (Jebsen and Klatt Reference Jebsen and Klatt2014; Fink Reference Fink1979) and World War II (Noack Reference Noack1991) but has resurfaced during the latest crisis in the Schleswig minority NTA in 2010–2012 when the Schleswig-Holstein government unilaterally reduced its funding of the minority schools (Kühl Reference Kühl2012; Klatt Reference Klatt2014; Hughes, Megoran, and Benwell Reference Hughes, Megoran and Benwell2020). This phenomenon of apparent nationality change still puzzles observers; and material reasons are still perceived as a driving factor especially in the southern parts of South Schleswig (Bittlinger Reference Bittlinger, Bendix, Ege, Hess, Lipp and Näser2020).

Nationalization processes, not only in borderlands, have been multifaceted and national indifference has remained an important category (Zahra Reference Zahra2010; Judson and Rozenblit Reference Judson and Rozenblit2005). It has also become academic standard to analyze identity not as a stable phenomenon but as a series of historical, individual, but also collective processes (among others, De Boer et al. Reference De Boer, Petersen, Spierings, Van der Velde, De Boer, Petersen, Spierings and Van der Velde2020). Spatial identities in Schleswig have remained far from clear during history (Klatt Reference Klatt, Andersen, Klatt and Sandberg2012). Waves of national mobilization could be tied to different social crises (Klatt Reference Klatt2019, Reference Klatt, de Boer, Petersen, Spierings and van der Velde2020). In the Kaiserreich, but also in the interwar years, social mobilization superseded national mobilization of Danish working-class members (Klatt Reference Klatt, Duhamelle, Kossert and Struck2007; Schartl Reference Schartl1999). Today, the high degree of mixed marriages and intercommunity mobility is also confirmed in a survey implemented in 2018 among high school students at the AP Møller School in Schleswig city: here, only 3 percent of the students came from families where both parents had attended a minority school, while another 30 percent came from families where one parent had attended a minority school. The remaining two-thirds came from parents who had not attended a minority school, which induced the author of the study, the school’s headmaster prof. Jørgen Kühl, to introduce the term post-national minority into minority studies to differentiate between a core group of minority members with multi-generational ties to the minority and a clear self-perception of being a part of the Danish nation and minority members with a looser connection to Danish nationality and a more bicultural self-perception (Kühl Reference Kühl and Kühl2018).

The following case study will illustrate how social and geographical mobility challenge the socially and, in my opinion, also geographically static concept of NTA.

A More Democratic Structure for the Danish Minority

Key focus of the following considerations is the question of implementation of NTA as a form of democratic minority self-governance in a setting with deeply felt reluctance to register minority membership and with high social mobility. Such a setting is not exclusive to South Schleswig, so this study can be classified as an instrumental case study demonstrating a general issue. Ultimately, minority membership is always subject to subjective self-identification, even though government regimes have attempted to introduce instruments of minority membership control. The most rigid cases are the public office quota-systems of South Tyrol and rigid systems of ethnically or religiously based power-sharing as in Bosnia-Hercegovina, Lebanon, and Iraq. NTA, in principle, does not imply such rigid quota-systems, but the dilemma of how to practically organize democratically legitimate NTA has already occupied its founding fathers (Goemans Reference Goemans, Nimni, Osippov and Smith2013).

It is not just a moral requirement but also self-constitutional that minority self-government should be based on democratic principles. Minority institutions such as minority schools are quasi-public institutions. They may be organized as associations or other forms of private institution, but they operate along similar public institutions and usually receive or aspire public funding on the same level as those public institutions. So how to organize democratic, legitimate minority self-governance? Concepts of territorial autonomy easily solve this issue by applying territorial criteria and institutions based on the political will of the citizens residing within this territory. With national minorities, this becomes more complicated, as they very often, for fear of discrimination, are reluctant to register their members. This reluctance increases when public authorities pursue the establishment of minority registers. Even identification in public censuses can be considered problematic and can be perceived as an instrument of state control and containment of minority groups. Furthermore, public registries demand clear-cut, either-or identifications, which may be challenging for socially integrated minorities.

In the following, I will illustrate this dilemma on the example of the debate within the Danish minority of South Schleswig to design a more effective, accountable, and democratic structure of the minority and its self-government – a discourse having gone on and off since the 2000s, with no clear outcome and so far no agreed nor implemented structural changes. In 2015, two employees of the Youth Organization initiated a more serious structural debate by threatening to leave the Samråd, demanding a professional analysis of the minority’s structural framework. The key point was the perceived ineffectiveness of the Samråd, accompanied by resource conflicts among its members and the lack of a joint minority leadership. In the following debate two core issues substantiated: the lack of a joint, democratically legitimate minority leadership and a competition between the cultural association SSF and the school association on defining the minority. Besides issues of democratic governance, the debate revolved around minority self-understanding and (re)bordering from majority society. A key focus point mobilizing the debate and the apparent necessity for change was the threat of closure of some rural minority schools. Here, many criticized that this decision would be taken by the School Association alone under the present structure. As the minority schools function as cultural centers and strongholds of the minority too, many argued for such decisions to be taken by the whole minority, not just the School Association.

My analysis of the debate and its impact on the NTA model in South Schleswig is based on a media analysis of the Danish minority daily newspaper Flensborg Avis’ coverage from June 1, 2017, to July 31, 2021, aggregated by a search on the Danish newspaper database Infomedia using the keywords mindretal (minority), struktur, and debat.

I have chosen four categories of analysis to structure the discourse reflected in the newspaper:

-

1. Democratic deficit: how the minority’s self-governing structure can improve democratic inclusion of its members

-

2. Efficiency and leadership: how the competition on financial resources can be overcome by a more wholesome governance representing and unifying the minority

-

3. Participation: how can users be transformed into members? Self-understanding of the minority

-

4. Resilience: there is no need to change the existing structure

On the base of these categories, 39 of the 179 hits could be selected as relevant for the analysis. Of these 39 articles, 8 directly represent personal opinions of stakeholders (e.g., letters to the editor, features).

1 Democratic deficit

Democratic deficit focused on the lack of a legitimate leadership of the minority, the undetermined decision procedures when more than one minority institution or association is involved and the lack of members’ influence in decision-making procedures (January 20, 2018, May 9, 2018, June 5, 2018, July 23, 2020, September 7, 2020, September 19, 2020). It was expressed in the wish to have a thorough structural reform, rebuilding the minority in a bottom-up process (March 22, 2018, November 9, 2018, March 28, 2019, August 12, 2020, June 5, 2021) – and more explicitly, forms of direct democracy with the possibility to have plebiscites where all minority members could vote on important issues as school closures were requested (March 22, 2018). Another important issue was the composition of the Samråd, where it was argued that not all members represented membership-based associations (April 27, 2019). This referred to institutional membership (e.g., of the library, of the newspaper) and, in consequence, the Samråd would not reflect the minority’s entirety democratically.

2 Efficiency and leadership

The arguments here are tightly connected to the issue of democratic deficit. They ask for a more stringent minority self-governance with a clear, democratically legitimate, and effective structure and leadership so the minority can speak with one voice. It concedes that the Samråd does not represent an institutional leadership but just a coordinating organ. This institutional leadership is deemed important for relations to kin-state and state of residence politicians and government, who often ask for a contact person or contact institution representing the minority as a whole (January 20, 2018, March 29, 2018, May 9, 2018, May 19, 2018, March 28, 2020, July 20, 2020, August 8, 2020, September 2, 2020, September 7, 2020, September 19, 2020, February 13, 2021, June 15, 2021, June 17/19, 2021).

It seems apparent that the powerful position of the School Association attained by its financial resources, large membership, and institutional strength is envied and challenged by the cultural association SSF, where many members would prefer an umbrella-structure headed by the SSF instead of the present system of principally autonomous associations operating alongside of each other (see also the “resilience” section below). This became apparent in the conflict on electing a new chairman for the Samråd in January 2021, where the School Association did not want to support SSF-chairman Gitte Hougaard Werner but motioned for the election of the provost of the Danish church as a perceived more neutral chairman to guide the minority through its structural reform process (January 20, 2021). The School Association, having the largest (obligatory) membership of all minority associations, defends its autonomy by arguing for its model of parental decision-power, whereas others prefer to extend ownership of the schools to the whole minority, not just those having children attending schools or kindergarten (April 27, 2019).

3 Participation

The discussion on participation focuses around two challenges: how to increase active participation in the minorities’ associations, especially the willingness to get elected to board positions, and on how to transform people characterized as users into what is understood to be minority members by the advocates of this discussion (June 11, 2017, May 17, 2018, August 23, 2018, April 27, 2019, June 5, 2020, August 5, 2020, October 17, 2020, February 13, 2021, June 17/19, 2021). The first issue is considered not to be minority-specific but reflecting a general societal trend of less commitment to volunteer work in civil society associations (June 5, 2020). The second, though, reflects a broader issue: what does it mean to be part of a national minority? How is minority membership identified? Are there other reasons to use minority institutions than a full national commitment and identification? This refers to what I have above described as social mobility also within the minority as well as the recruitment of families who send their children to attend a minority kindergarten and school without necessarily having had any social connection or relation with the minority associations before. As mentioned above, the principle of subjective self-identification opens for selecting the minority without fulfilling any objective criteria as Danish heritage or linguistic competencies. The discussion around minority self-governance and structure here focuses on a narrative of a need to (re)develop a “true” minority community (June 11, 2017, May 17, 2018, August 23, 2018, April 27, 2019, Oct 17, 2020). This implies a distinction between real members and people characterized as users or shoppers not choosing the full package. The minority perceives pressure from some Danish politicians to attend to this issue to secure kin-state funding in the future (August 23, 2018).

In effect, this perceived shopping or using instead of full membership is exemplified by the following practices:

-

1. Lack of political solidarity by not voting for the minority party or even being a member of (or a local candidate for) a mainstream political party

-

2. Not speaking or learning the Danish language

-

3. Removing a child (for whatever reason) from the minority schools

-

4. Attending something other than the minority church congregations

-

5. Choosing a German sports club or, alternatively, joining a Danish sports club for material reasons

Proponents for the need to ensure structural reform to more actively engage users as members argue that minority self-understanding – as a clear, lifelong decision of full commitment – is decisive. Minor issues were measures to increase board membership of young members (December 13, 2018, July 16, 2020, September 7, 2020, April 24, 2021).

4 Resilience to changes

Arguments of resilience focused on the advantage of having strong, member-driven associations responsible for the minority’s institutions and ensuring a colorful, wide-ranging, all-encompassing minority life (May 4, 2018, January 10, 2019). Here, the School Association stands in the forefront, defending its model of parent influence and ownership of their children’s kindergartens and schools. Core conflict is the challenge to this argument – namely that the educational facilities are pivotal instruments to develop and disseminate Danish language, culture, and identity in South Schleswig and thus belong to the whole minority, not just the parents. There is an undertone and concerning point regarding participation in that proponents of the all-minority ownership of the schools suspect School Association members to not be full minority members, but users only. Later in 2020, identification was deemed a precondition for structural changes; the argument was that the minority needed to know who they are and who they want to be in the future before it could design a structure to implement this vision (October 17, 2020).

Possible New Structures

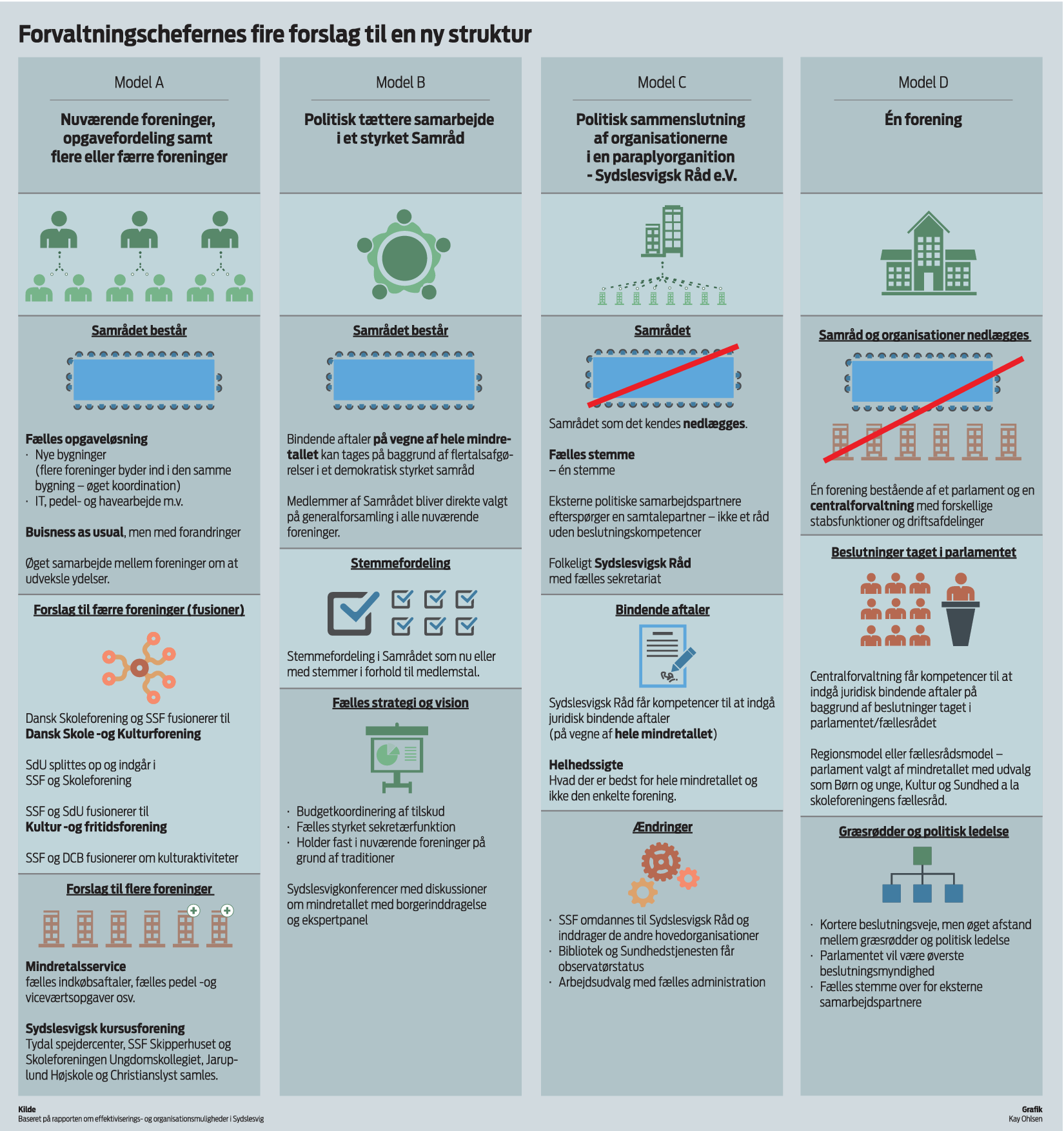

The nine administrative directors of all the minority’s institutions collaborated on a study on the minority’s administrative structure to have a basis for negotiation, which was presented in June 2020. It suggested four models for the minority’s future self-governance:

Figure 1 illustrates the models discussed. Model A is based on the present structure but envisages a merger of the three largest associations within the minority, the school association Dansk Skoleforening for Sydslesvig, the cultural association Sydslesvigsk Forening, SSF (South-Schleswigian Association), and the youth associations’ umbrella association Sydslesvigs danske ungdomsforeninger, into two new associations: a School- and Culture Association and a Culture- and Leisure Association. This would put an end to the rivalry between the SSF, which often is perceived (and maintains to be) the core minority’s association, and the School Association, which by offering education and by attracting new families to the minority plays a key role to maintain it. Model B transforms the present Samråd from a coordination forum to a decision-making assembly of delegates elected by the different associations on their annual business meetings. This would create a members-based minority parliament to make all key decisions, based on majority voting. Model C intends to unite the different minority association into an umbrella organization Sydslesvigsk Råd (South Schleswigian Council) that would be membership based. This Council should have a secretariat and competence to sign binding legal agreements for the whole minority. It should also function as contact point for external cooperation with majority civil society as well as majority and kin-state politicians. The key argument provided for model C is that it will strengthen the minority politically, as the council will have full decision-making competence and be the minority’s spokesperson (Flensborg Avis, June 4, 2020). In effect, it would empower the minority’s general secretary and the joint chairman to represent a minority government. Model D will merge all minority associations to form one association, with a parliament, including parliamentary committees, elected by minority members, and a single administration. Although not directly outspoken in the draft, this would imply a form of registration of minority membership in a cadaster, a breach with the tradition of non-registration. According to the authors, every aspect was on the table, and there were no taboos (Flensborg Avis, June 5, 2020). The authors’ perception of major challenges were digitalization and individualization (e.g., fewer people committed themselves to voluntary work, fewer people attended events), globalization (e.g., being national becoming out of fashion, minority institutions as a form of globalized education, which is in conflict with the self-understanding of the School Association). For the authors, this implied that the minority needed to be more conscious about itself and what it means to be a national minority (ibid.).

Figure 1. Flensborg Avis, June 4, 2020, p. 8.

The different models were discussed informally over the summer of 2020, facilitated by the minority’s newspaper Flensborg Avis (July 16, 20, 23, 27, 31, August 5, 8, 12). In different “structural picknicks” around South Schleswig, different stakeholders in the minority were asked to discuss structure based on the models proposed. These picknicks, as presented in the newspaper, were carried through in a friendly atmosphere. Lego bricks were available to visualize different models of how to organize the minority. While thus being very open and diverse, there was consensus on the present structure being problematic with regard to democracy and inclusion of minority members. Surprisingly, the democratic element had a spatial dimension, with complaints about the dominance of Flensburg over the remainder of South Schleswig. Many criticized that power was concentrated in Flensburg, where the minority institutions have their headquarters. Another issue was lack of commitment to voluntary work from members as well as institutional staff and a hope that this could improve with a more democratic, inclusive organizational structure. Concretely, this did not materialize, and neither was there much open approval of one of the four models. Just one district chair clearly approved model D and argued explicitly that the Danish minority in South Schleswig should be organized as Denmark’s 99th municipality (Flensborg Avis, August 8, 2020). The chairman of the South Schleswig Association announced in September 2020 that the formal debate on the future structure of the minority would be postponed to 2021, “when the members will be included in depth into the debate” (my translation, Flensborg Avis, September 15, 2020).

On June 12, 2021, the Samråd reopened the debate at a closed meeting with input from kin-state stakeholders (Flensborg Avis, June 9, 2021). This was a new turn, as kin-state representatives had hitherto been rather reluctant on advising the minority about its internal structure. In the meeting, former Danish minister of culture and former chairman of Grænseforeningen, Mette Bock, encouraged starting a discussion about replacing the Samråd, an institution without a democratic mandate, with an elected body (Flensborg Avis, June 15, 2021). Henrik Becker-Christensen, a historian and Danish Consul General in Flensburg from 1998 to 2017, suggested strengthening the Samråd by introducing majority voting and supplementing it with a broader South Schleswig Council (Flensborg Avis, June 17/19).

Conclusion

The structural debate documents the difficulties of designing acceptable, effective, and viable models of NTA. The dilemmas outlined may be characteristic for the Danish minority of South Schleswig with only limited transferability; South Schleswig is considered a best-practice case of minority accommodation and social integration where minority institutions are chosen for their quality. This may not be the case in other minority regions, although empirical evidence is often incomplete. Transferability can be expected with regard to the dilemma of minority registration to derive democratic legitimacy of NTA institutions, as the reluctance to use public registries of minority membership is not exclusive to Schleswig. The appeasement of a minority conflict is not exclusive to Schleswig either, nor is social and geographic mobility out of and into the minority or its historic space of residence. It must be expected that many minorities in Europe face issues of out-migration and voluntary assimilation. For the specific case of Schleswig, the difficulty of how to establish a democratically legitimate NTA structure is apparent, especially when the SSF chairman claimed the need for a vision of what the Danish minority should be before debating its organizational structure (Flensborg Avis, October 17, 2020), followed by a restart of a debate of who is minority and who is (just) a user or shopper. The bordering of a minority, which is perceived as a best practice of social integration, apparently challenges daily living practices in South Schleswig. Is the minority killed by its success? Or, more blatantly, should we rethink the concept of national minority in light of European integration and globalization? This challenges the Schleswig-narrative of “Vom Gegeneinander zum Füreinander” (literally, “from against one another to for one another,” meaning a transformation of the conflict from adversarial communities to separate, but socially and economically integrated, cooperative communities).

The non-definition of “minority” based on objective, measurable criteria is rooted in the region’s – but also European – history and the attempt to containerize nations into homogeneous territories. Social practices make it impossible to define the minorities as core, stable communities – which complicates the governing of NTA as well as its institutional legitimacy and the legitimacy of kin-state funding. The latter is pivotal for the continuation of the impressive institutional framework, especially the minority schools. Above it has been demonstrated that high social and geographical mobility make it difficult to apply a geographically based national minority concept in Schleswig. Minority mobility in Schleswig has been crossing two geographical borders: the German-Danish national border (as minority-kin state mobility) and the border between South Schleswig and the rest of Germany. It has also been crossing sociocultural borders in an ongoing process of nationalization and denationalization. As demonstrated, both mobilities have been perceived as threatening to the existence of a stable national minority as a distinguishable group in Schleswig. Border-crossing social practices do not harmonize with imaginaries of a stable, containerized national minority. Border Studies has developed the concepts of transnational borderlanders and regionauts to describe these processes outside the containerizing terminology of national belonging as the supreme and only form of identity. Transnational borderlanders are residents of a borderland who move between cultures, cross borders regularly, are bilingual, and appreciate living in a borderland in between two nation states (Martinez Reference Martinez1994). Regionauts are borderland residents who fully exploit the duality of a borderland, developing social and cultural competencies to use the entire borderland as a living space (Löfgren Reference Löfgren2008; O’Dell Reference O’Dell2003).

These concepts could describe what is perceived deprecatingly as users and shoppers by core minority members. It could also be perceived as the result of the key Schleswig-narrative of the European model of reconciliation. For NTA, this implies a rethinking of accommodating cultural diversity in a more flexible and inclusive setting, acknowledging the borderland reality and regional history of a common space – a common space that has been divided by forceful national movements but nonetheless has resilience with regard to national homogenization and the capacity to revive diversity without challenging territorial integrity. For Schleswig, as for other border and minority regions, this would mean acknowledging the multiple complexities of Danish, German, and regional sociocultural aspects of borderland life. An NTA structure should therefore ensure the acceptance of diverse approaches to borderland life but also guarantee the opportunity to live as a Dane in Germany, which, in effect, means solid, sustainable models to finance this special cultural and linguist borderland diversity. This, I would argue, is best achieved by strong, functional, membership-based associations operating within state of residence-laws and institutions that are committed to ensuring borderland diversity.

Disclosures

This research was produced within the COST Action European Non-Territorial Autonomy Network.