Introduction

Located in the Zagros Mountains of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, close to the border with modern day Turkey and in the governorate of Dohuk, the citadel town of Amadiya/Amedi stands perched on a magnificent rocky height, visible in the landscape from a far distance (Fig. 1). At 1985 m above sea level, it is a naturally fortified location. According to the Arabic language historical accounts of the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries A.D., the citadel of Amadiya was built by the Seljuk emir, Imad al Din Zengi (c. 1085–1146 A.D.).Footnote 1 However, contemporaneous Arabic sources and earlier architectural remains within and around the citadel both indicate clearly that it had already been occupied long before. This essay presents an analysis of three rock reliefs that the Columbia University Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments survey (MMM) documented in 2013 and revisited for a second examination on site in 2018. As the nearby city of Mosul fell to the violence and terror of the Islamic State (DAESH) and was occupied by them soon after our work there in the 2013 field season, a joint decision was made, in consultation with Iraqi colleagues, not to publicize any of the work of the MMM project or these reliefs at that time, but instead to wait until a later date so as not to draw attention to the locations of rock reliefs or historical architecture.Footnote 2 Therefore, soon after our first field season in Amadiya/Amedi, the Columbia project provided a report of the reliefs and architecture on a password protected website, which gave historical information, detailed photography and processed immersive panoramas, making them accessible to registered colleagues and students only.Footnote 3 Six years on, we are cautiously beginning to make this work more widely available.

Fig. 1 Amadiya/Amedi in the landscape, view from a distance; arrow points to location of Bahdinan Gate and reliefs. ©The Trustees of Columbia University, Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments, photo: Serdar Yalcin.

The work of the MMM survey project, directed by Zainab Bahrani and initiated in 2012, has aimed to document historical architecture and rock reliefs throughout the region. We have so far documented eighteen rock relief sites, some of which have multiple reliefs, and compiled a large database of images, processed panoramas, and photogrammetric data. We have also documented numerous monuments and historical architectural structures throughout the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and South-eastern Turkey. Each monument or building on the website is mapped and accompanied by visual descriptions and historical information, as well as basic bibliographic resources. Our field methods rely on photogrammetry, perspectival corrective architectural stills and perspective controlled stills, close details, Gigapan imaging and 360° immersive processed panoramas. The latter method, derived from the techniques of architectural historical study of buildings, is one that the MMM project developed and adapted for use in the contextual analysis of rock reliefs, their spatial setting and significance within the landscape.Footnote 4

The MMM project's documentation of the rock reliefs near the Bahdinan/Mosul Gate began in 2013 (Fig. 2). As this work was part of the larger multi-year survey, still in progress today, the larger description of this project, its sites and methodologies, will be published separately. A new Columbia University preservation project in Amadiya/Amedi, also directed by Zainab Bahrani, will begin in August 2019 when the focus will be on the restoration of the Bahdinan Gate and the conservation of the Parthian reliefs and ancient stairway path. However, as it is relevant to the present study, it is important to note that the aim of MMM, as envisioned from the start, was to document historical architecture and monuments without restriction of the area of study by any chronological or dynastic parameters, and without limiting it to a particular medium or form of monument.Footnote 5 Our work insists on the contextualization of monuments diachronically as well as spatially, crossing traditional disciplinary borders of Islamic and pre-Islamic scholarship on historical monuments and sites. We argue also that the citadel of Amadiya/Amedi can therefore be studied as a comprehensive site of the Mesopotamian region's historical integration of the remains of the pre-Islamic past, rather than their rejection.

Fig. 2 Amadiya/Amedi, view of approach to Mosul/Bahdinan Gate. ©The Trustees of Columbia University, Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments, photo: Zainab Bahrani.

Built as an acropolis that utilizes the natural defences of a steep and formidable access, the elliptically shaped citadel is entered by two main monumental portals that remain today. The Zebari gate, first built in the late eleventh or twelfth century A.D., was demolished in the 1930s and has been completely reconstructed in recent years. The second main portal is the Mosul Gate, also called the Bahdinan Gate.Footnote 6 Although it was restored in the second half of the twentieth century with an incorrect positioning of the sculpted spandrel blocks, it retains much of its original structure and reliefs from the twelfth century, albeit haphazardly reinserted into the original portal (Fig. 3). The original arrangement can be seen in earlier twentieth century photographs of the gate, before restoration (Fig. 4). According to Yakut al-Rumi al-Baghdadi al-Hamawi, Amadiya was built in 537 Hijra (1142 A.D.) by Imad al-Din Zengi (1085–1146 A.D.), and the current name Amadiya/Amedi is after his name. However, according to Yakut al-Rumi, the Zengid citadel was not a new construction but was built upon an earlier Kurdish fortification called Ashib.Footnote 7 Inside the city of Amadiya, we documented the remains of a fairly well preserved small early Christian church and other historical architecture that is better known within the citadel, but little archaeological work or architectural surveys have been conducted here in recent years, despite the fact that these remains and the rock reliefs were already noted by European travellers in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. However, it is architecturally clear that the city of Amadiya/Amedi had centuries of existence before the Zengid dynasty made it a centre of its power.Footnote 8

Fig. 3 Mosul/Bahdinan Gate detail, c. 1142 A.D., current condition. ©The Trustees of Columbia University, Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments, photo: Helen Malko.

Fig. 4 Mosul/Bahdinan Gate, c. 1142 A.D., early twentieth century. Photo: Tariq Jawad al-Janabi, 1983, Dirasat fi al imarah al-Iraqiya fi al Usur al Wusta, Baghdad, State Organization of Antiquities and Heritage.

The Reliefs

The three reliefs are visible on the cliff face, as one walks out of the Mosul or Bahdinan Gate and looks to the right (Fig. 5), each one set within a large niche cut into the living rock of the cliff face. Each niche has an arched curve at the upper part, typical of the Mesopotamian stele shape. The largest of the reliefs is 2.81 m in height and 1.54 m wide, making it over life size and imposing in scale. The stele outline of the reliefs was already known in earlier Mesopotamian sculpture and is visible, for example, at nearby sites such as Khennis. It was used as a form of framing in rock reliefs of the Neo-Assyrian era, directly quoting the contours of a stele (narû), as I have pointed out elsewhere.Footnote 9 Dating sometime between the first century B.C. and the late second century A.D. in our assessment, the Amadiya reliefs thus relied upon an existing narû form for monumental sculpture that had been transferred to rock reliefs in earlier centuries, and which could still be seen in the region. The Assyrian stele shape was also used in the Parthian relief stelae erected in Assur, now in the Istanbul Archaeological Museum.Footnote 10 The shape of the relief niches is a good indication that here are a series of Parthian, rather than Sasanian reliefs.

Fig. 5 Stairway path next to Relief 1. ©The Trustees of Columbia University, Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments, photo: Zainab Bahrani.

Starting with the first relief, the one that is closest to the Zengid portal, we numbered the reliefs from 1–3, although the numbering is not meant to indicate dating or the order in which they were carved in antiquity. The reliefs follow the slope of the stairway, outside the citadel. Here, a description is provided of each relief, followed by a section with comparisons. As the reliefs are very worn, we produced a series of images for each one, including photogrammetry, perspectival corrected and perspective controlled stills, and detailed shots that were studied together with on-site observation both at the time of the documentation in 2013 and in a follow up 2018 field trip in which we checked our data and interpretations on site. Each relief description is thus based on an analysis of a range of images and multiple angles. The line drawings indicate the remaining visible traces of carved lines, where we were able to see them. For the contextual recording in space, we used Gigapan imaging and immersive processed panoramas. These interactive panoramas are high resolution and can be zoomed in for closer details in context. Nevertheless, the presentations of the reliefs here must be understood as interpretations of the visual data. Although digital image capture is at times described by archaeologists as a scientifically objective and unmediated form of image making that directly reflects the original, scholars in the fields of critical Visual Studies and in the History of Science and Technology have at the same time cautioned against an unproblematic idea of mechanical objectivity. As much as we aim for accuracy in our work, we remain well aware that readings and reconstructions based on new technologies are not a panacea for the study of ancient remains, but are also mediated and interpretive forms of representation. As such, they are also subject to visual theories of representation and critical historical analyses.

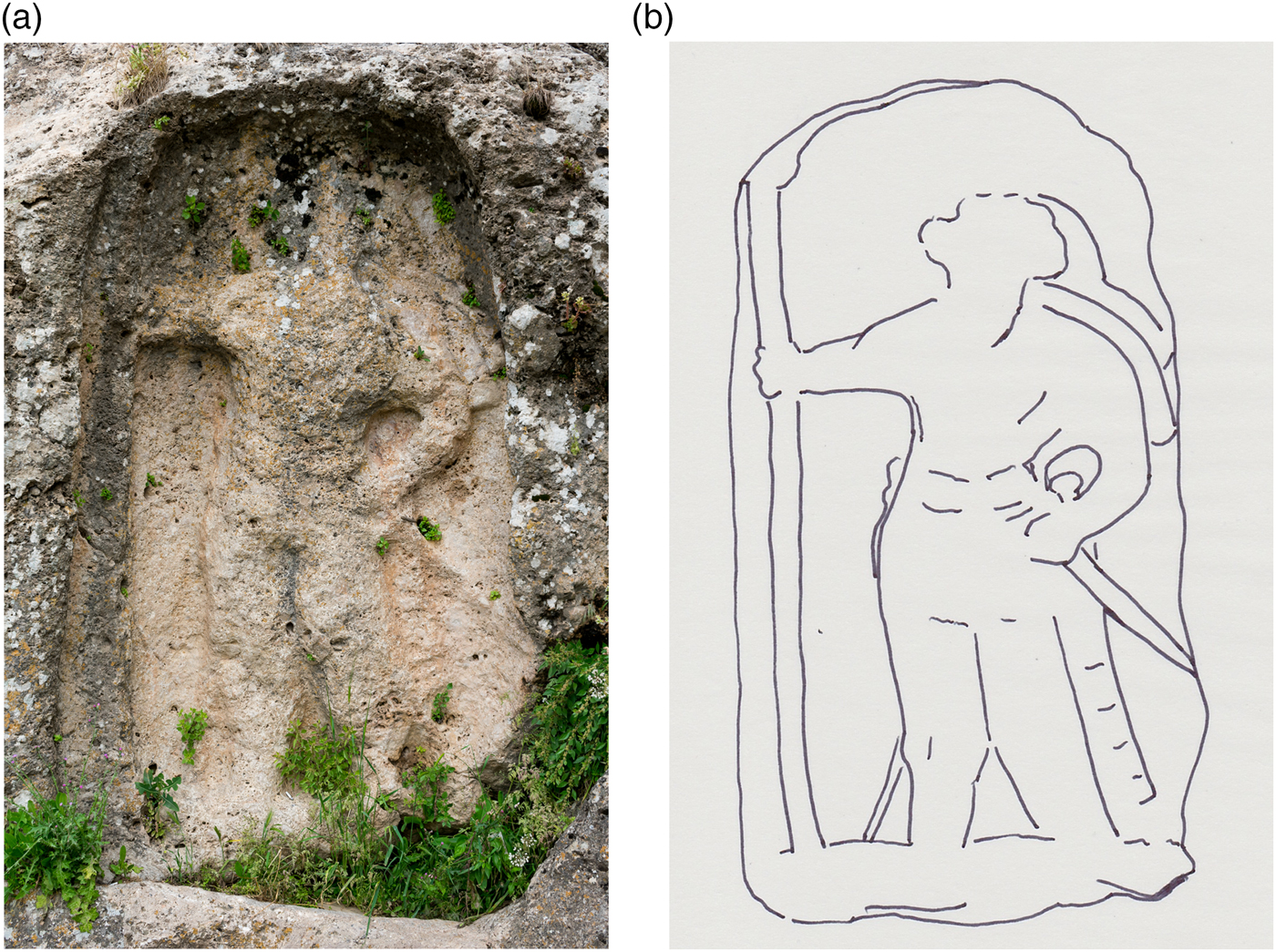

Relief 1:

A full scale frontal male figure in a stele-shaped niche

2.81m x 1.54 m (at widest point).

Description (Figs. 6a, b, 7):

Fig. 6 Relief 1, Standing male figure in frontal position. ©The Trustees of Columbia University, Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments, 6a photo: Gabriel Rodriguez; 6b: line drawing.

Fig. 7 Relief 1, photogrammetry, tilted from the side. ©The Trustees of Columbia University, Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments. Photogrammetry: Gabriel Rodriguez.

An upright, full-scale figure of a man stands in a frontal position. His upper body leans somewhat to his left, giving the figure a slightly curving torso and a jutting out right hip, while his left arm is bent and his hand rests on his left hip. The right arm is stretched out to hold a long spear or staff at his right side, with the hand grasping the spear or staff just above the outstretched elbow level, visible in the tilted photogrammetry image (Fig. 7). It is surmounted by a bell-shaped curving element. This spear/staff fills the entire length of the relief space, creating a framing element at the figure's right. The figure appears to be wearing long trousers that narrow at the ankles. The face and head are worn, but traces of the hairstyle and headdress are visible. He has a thick hairstyle with rounded tufts that reach to a level above the shoulders on either side and are especially clear at the figure's left side. The evidence for a beard is unclear, but an area at the upper chest, in higher relief, can be identified as the trace of one. Emanating from the area at the back of his head, a pair of long flowing ribbons or fillets billow to the left side of the figure, curving along the shoulder and flowing down to just above the left elbow. Another semi-circular element, which does not appear to be part of the fillets, seems to frame the head in a semi-circular form and is visible to the figure's upper left.

At his left side, two weapons can be seen clearly: a long broad sword follows the line of his leg and ends at the foot, while at right angles, from the man's hand out to the edge of the relief space, a long thin sword can be seen. Another clear detail here is the knob of the blade handle or pommel that can be seen in the space between the bent elbow and the curve of his waist. On the right side, along the upper thigh and the waist, is a curving, serpentine line. Below this line are the traces of what may be yet another weapon, discernable just to the side of the lower right leg. Thus both at his left and right, the weapons that he grasps reach the boundaries of the relief space, while the male figure himself takes up most of the pictorial space of the relief. The relief is worn with time and exposure to the elements. However, a close study of the surface does not give any indication that it has been deliberately effaced. The sway in the body that results from the curve of the torso indicates a shift in balance that points to the sculptor's familiarity with the contrapposto stance that is particularly known from the sculptures of Hatra. The modelling of the figure and its proportions and frontal composition, the hairstyle, the clothing and headdress with long ribbons all have parallels in Parthian era art.

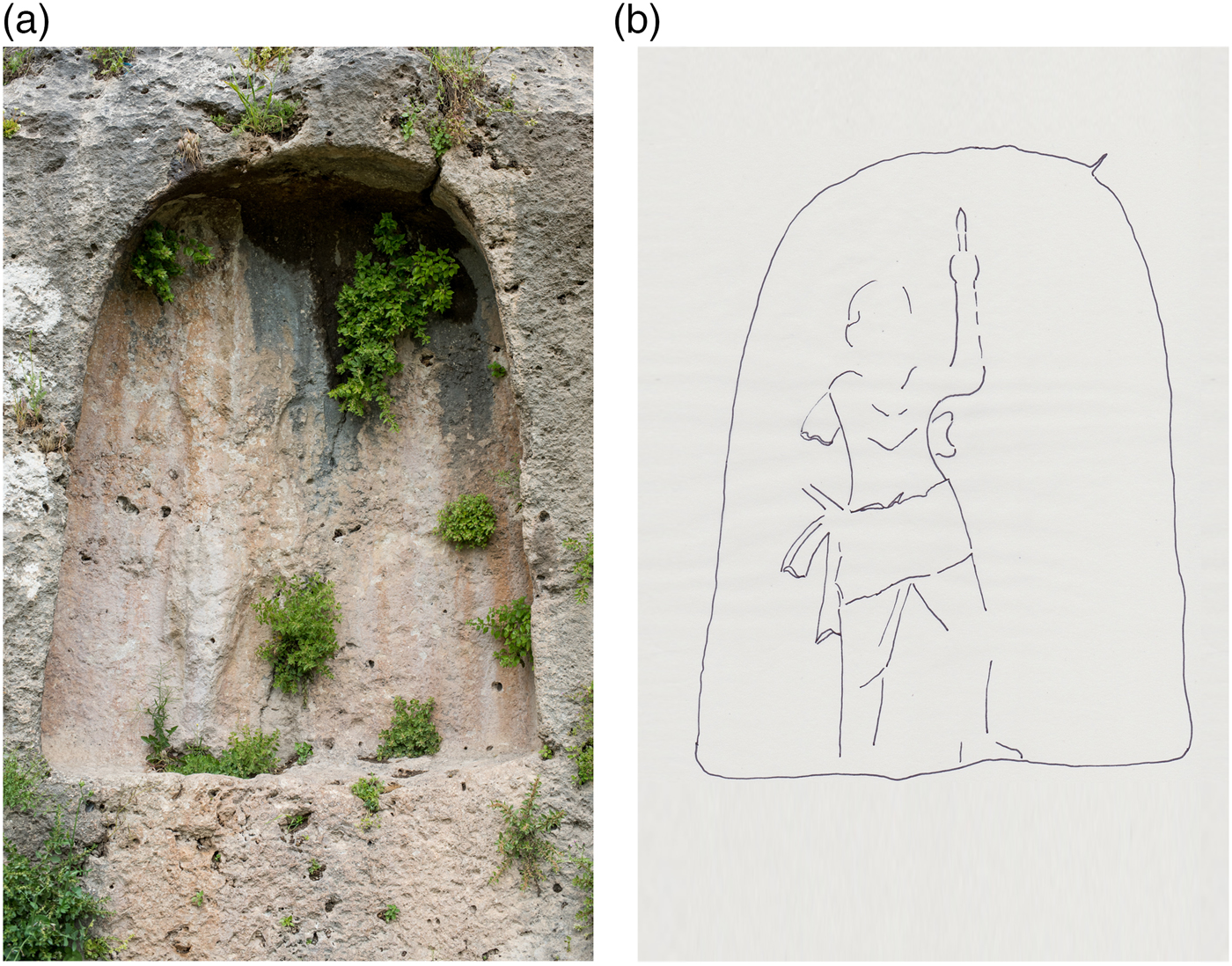

Relief 2

A full scale standing female figure in a relief niche

2.35 m x 1.61 m

Description (Figs. 8a, b, 9)

Fig. 8 Relief 2, Standing female figure. ©The Trustees of Columbia University, Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments, 8a: photo: Serdar Yalcin; 8b: line drawing.

Fig. 9 Relief 2, tilted photogrammetry image to reveal elevation of carved surface. ©The Trustees of Columbia University, Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments, photogrammetry: Gabriel Rodriguez.

This second relief is placed along the downward slope of the external stairway of the citadel. It is the most worn of the three reliefs at Amadiya and appears in the middle between the other two. The contours of the relief space are slightly more rounded at the lower part, and the niche is slightly smaller than those of the other two reliefs. Here, although the relief niche is heavily worn and has been described as empty by earlier European travellers and commentators, the traces of a standing robed figure can be discerned (Figs. 8, 9). Despite earlier descriptions of this niche as empty, Dlshad Marf Zamua recognised a clothed figure here in his Reference Marf Zamua2008 publication of the reliefs.Footnote 11 The relief is in a location that is more exposed than Relief 1, and the surface is extremely weathered. In addition, the rock has a great deal of foliage emerging from behind, as does the third relief. The foliage outgrowth can be removed in a corrected photogrammetry image (ortho-photo), but the area where the foliage has already damaged the rock does not reveal the original surface in that case, only a lacuna or dark spot where it has been damaged. The corrected image would therefore require a certain amount of reconstruction of areas that might be mistakenly read as accurate or intact rock surface on the rectified model or image.

The top area where a head might have been is very worn and damaged by the growth of foliage in the stone, but the slope of the figure's left shoulder can be seen and traces of the body, or rather the garment, are visible. The figure, which may be a female figure, seems to be wearing a Greek style chiton and himation dress. The folds of the overlying himation are diagonally pleated across the body and seem to be pulled to the side and held with her left hand in a typical stance associated with art of the Seleucid and Parthian eras (see comparisons below). As the head area leaves a great deal of space in the niche, proportionately for the composition, we can conjecture that a headdress appeared at the top, and a few traces of short vertical lines may indicate such a headdress. Near the figure's left foot seems to be an object that resembles an oval shield, although this is by no means certain. To the opposite side, at the figure's right, the space of the relief and the expected balance of the composition indicates that the figure held something before her or to her side. There is no visible evidence there, but based on the space and on comparative material we might speculate that something such as a spear or standard, or a palm frond, was depicted there, in a similar way to the representations of goddesses on Parthian coins.

Relief 3

A full scale male figure in profile in a stele shaped niche

2.21 m x 1.79 m (width at base)

Description (Figs. 10a, b, 11, 12):

Fig. 10 Relief 3, Male figure in profile. ©The Trustees of Columbia University, Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments, 10a: photo: Gabriel Rodriguez; 10b: line drawing.

Fig. 11 Relief 3, Profile view of male figure striding upwards, tilted photogrammetry. ©The Trustees of Columbia University, Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments. Photogrammetry: Gabriel Rodriguez.

Fig. 12 Relief 3, photogrammetry model, desaturated and with increased outlining of surface. ©The Trustees of Columbia University, Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments. Photogrammetry: Gabriel Rodriguez.

This stele shaped niche with an arched top has the deepest set relief space of the three, and is placed some way farther down the external stairway of the citadel. The niche narrows towards the top and is wider at the base. The figure set within this space is carved in a different style and with different proportions than those of the first relief. It is a depiction of a male figure in profile view rather than a frontal image, and his upper body is slightly leaning back, conveying upward movement. In terms of modelling and carving, it is a different form of sculpture, with more rounded modelling of the body and elongated proportions. We thus see here a different style from Relief 1. The figure is in a striding position, moving upwards towards the right side of the relief, as if in a climbing posture. We see the right side of his body and traces of his head, his right arm slightly raised, bent at the elbow across his chest. His movement is aligned with the slope of the stairway, climbing up, approaching the citadel entrance, and thus echoes the movement of the visitor on the upward climb. He is larger than life size and fills much of the height of the relief space. Behind the figure, at the left side of the relief, and behind his right leg and hip, we see what appear to be ribbons of cloth, perhaps parts of a cloth belt or a cloak and what may be the traces of a weapon. The figure is wearing a short tunic that ends at the knees with a tight fitting bodice or cuirass. Behind the figure's right shoulder are the traces of the ends of a cloth that may be understood as a part of a fillet streaming down from the head. However, given its location and curve at the figure's back, another possible reading is that it emerges from another article of clothing such as a short cloak or chlamys (Fig. 11). The lower part of this cloth is not straight or pleated, but appears to have a thick, curving pattern at the lower edge. The figure seems to have held a spear raised by the left arm, as traces of something pointed can be seen on the corrected photogrammetry image (Fig. 12). A curving object appears at the right side of the waist.

Identification and date

Relief 1

Although there are no exact parallels for any of the Amadiya reliefs, a frontal male figure appearing on a rock relief can be compared in a very general way to the Parthian reliefs in Iran at Tang-i-Sarwak and the Parthian stones at Bisotun.Footnote 12 The frontality of the figure, the rounded sloping outlines of the body, the tufted hairstyle and the positioning and grasp of the weapons all have similarities with Parthian images. The sway of the torso, however, indicates a familiarity with, and interest in, contrapposto in the representation of the body. This movement of the body is found in many sculptures from Hatra, making this relief more similar to Hatrene sculpture than to the more emphatically linear Parthian reliefs in Iran. There we see the use of contrapposto in Sasanian art, but the depiction of emphatically billowing drapery in Sasanian art differs from the Amadiya reliefs, and as we have stated above, the stele shaped niches are another indication of Parthian date. Compared to the Bisotun frontal figures, the Parthian figure in the Amadiya Relief 1 has slimmer proportions and far more movement in his stance, more similar to the sculptures of Hatra. The figure also bears some other similarities with representations of some sculpted figures from Hatra, where male gods are sometimes shown bearing a large staff or standard and wrapping the right hand around the staff, while placing the left hand on a dagger or sword.Footnote 13

The frontal figure in Relief 1 may represent a prince of the region, but an identification of the figure as a divinity cannot be ruled out and indeed is equally plausible, if we consider that the stylistic parallels at Hatra are with divine warrior images. When Parthian princes are represented on rock reliefs, such as those at Merquly and Rabbana (although they are in profile), or in the numerous statues in the round of royal men from Hatra, they tend to favour a pose with upraised right arm and with an upheld palm of the right hand which is not the case with the figure in Relief 1.Footnote 14 The royal figures on rock reliefs also wear longer clothing with looser cloaks covering the forms of the body, the outlines of which are not visible, as they are here. Relief 1 is different in proportions and has a more rounded carving style than the more linear carving of the reliefs at Merquly and Rabbana. Nor is it similar to the stillness and linearity of the contemporaneous Parthian reliefs in Iran mentioned above. Although the parallels with Hatra sculpture are not exact, Relief 1 most closely resembles works from Hatra, in terms of composition and in terms of the contrapposto S curve of the frontal depiction of the body and its disposition, as well as in the positioning of the body and the grasp of the weapons. At Hatra, these features are to be found particularly in representations of male divinities rather than royal figures. This relief is thus better understood as a divine warrior figure who guards the entrance into the citadel. Divine warrior figures that are guardians of the gate are also known from inscriptions of this period.Footnote 15

Relief 2

In this relief, the standing figure, if our reading is correct, wears similar clothing to Parthian period female figures known both from the south of Mesopotamia and from Hatra. The figure may represent a type of city Tyche, or Fortune, perhaps comparable to images that can be seen on coins of the Parthian period, with parallels among those minted at Seleucia-on-the-Tigris.Footnote 16 This iconography is also well known at Hatra. The figure in Relief 2 may best be identified as an Allat-Athena type, however, because of the diagonal drapery and the possible oval shield at her side.Footnote 17 Such iconography is known in the mid second century. Whatever her identity, the pleats of the clothing drawn to the side in a diagonal are commonly found in Parthian era statues in the round that represent women, and also in images of goddesses on coins.

Relief 3

The figure in this relief may conceivably have represented a living ruler given the profile view, but it is difficult to reach a conclusion with any certainty. There are some significant differences with ruler images of the Parthian era that must be pointed out. The figure appears to wear a Hatrene type dress with tight bodice and perhaps a cloak or chlamys. Ruler images on rock reliefs, such as those at Merquly and Rabbana or the image at the Batas Herir rock relief, wear a different, looser dress and a headdress with thin strips of ribbon, usually streaming outward as two fillets. Those reliefs, all of which have also been studied on site and documented by the MMM team, are carved in a blockier and more linear style than this lighter, modelled figure who leans back slightly and climbs upwards.Footnote 18 They reveal little of the outlines of the physical form. The ruler figures depicted in rock reliefs and in sculpture in the round are generally depicted with their hand up, and palm open. This is not the case with Relief 3, where the right arm is not raised up, even though the position of the right hand against the body is not entirely clear.

The relief has a distinctively different carving style from Relief 1 as we have already stated above, and this may indicate a different, earlier date. The naturalistic modelling of the leg that is still visible, as well as the dynamic movement of the body, suggest an early date in the Parthian period, when Greek Hellenistic influences were stronger in Parthian art, and possibly as early as the first century B.C. The female figure of Relief 2 may well be of the same early date. However, such styles continued to be used in Mesopotamia during the entirety of the Parthian era. Whether or not the frontal male was carved at the same time as the other two reliefs or at a later date is open to question. As Stefan Hauser has rightly pointed out in his work on the Parthians, there is no need to assume that different styles did not co-exist.Footnote 19 Therefore, it is possible to suggest a date sometime between the first century B.C. and the late second century A.D. Although such a major carving project must have been the result of a royal command, and Amedi was surely an important fortress in the Parthian era and probably earlier, it is not possible to identify the name of a particular ruler or historical event in association with these reliefs, as we can for the Seljuk era Zengid citadel that incorporated the reliefs in its reutilisation of the site.

Relief 3 is in a strategic spot on the cliff face, just where the stairs give access to the citadel turn (Fig. 13). One encounters it first when climbing the steep height from the valley to the citadel entranceway. Upon approaching the relief, one makes a 90-degree turn to approach the portal. The position of this relief in particular indicates that the original approach to the citadel utilised by the Zengid dynasty builders followed the earlier path to the entrance, and that the citadel of Amadiya was already an acropolis in the Parthian era. The figure's upward climb and position indicate clearly that it was carved in relation to an incline that was in use. A close analysis of the steps that lead up from the valley revealed original post-holes in several locations, and the relation of the blocks to the cliff face and to the citadel entry, as well as the way that they are hewn, indicates that the stepped path is to be dated to the Parthian era, continuing to be utilised and repaired during the Zengid dynasty. The position of Relief 1, the frontal figure, was also therefore at the entrance of the Parthian era citadel. Relief 3 was placed at a pivotal position, a turning point in the path that leads upwards. It was the first relief that one saw from the original ancient approach, and it faced the direction of the ancient entrance. The image was certainly carved in relation to the original upward climb. Thus, in a similar way to the position of the Merquly and Rabbana reliefs, the reliefs are placed at significant approaches to a settlement or fortress.

Fig. 13 Approach to Relief 3 with ancient stepped path. ©The Trustees of Columbia University, Mapping Mesopotamian Monuments, photo: Zainab Bahrani

A study of the rock surfaces indicates that the reliefs are not fully effaced, although the surfaces are in poor condition. The relief closest to the portal is best preserved because of its physical location, less exposed to the elements than the other two that lie farther down the stepped path. The twelfth century Mosul or Bahdinan Gate, and the Zengid fortifications and settlement, were constructed without an attempt to remove these pre-Islamic reliefs, which remained so highly visible on the main approach up from the valley to the acropolis. These reliefs are the first things one encounters upon the approach from the valley below.Footnote 20 In fact not only did the twelfth century architects leave the reliefs in place, they also seem to have followed the original entrance approach, and the Zengid prince commissioned relief sculptures above the arch of his own great portal to complement the existing ones. The Zengid reliefs on the great portal show bearded heroes on the spandrels with entwined serpents and decorative foliage in between them, while a sunburst with a rounded human face emerges at the centre above the keystone, where the entwined necks of the serpents meet. The frame of this remarkable scene, which is rich with ancient imagery, seems to emerge from a tree, positioned right next to the serpents, sprouts and forks off into two directions, to form the outer frame of the composition (Figs. 2, 3).Footnote 21 We can then conclude that the Parthian reliefs were not simply disregarded in later centuries, but were retained in place at the citadel entry, and also became a source of inspiration for the Zengid Mosul Gate, which played off the imagery and created its own images in dialogue with the past.

Acknowledgements

The MMM team is composed of Columbia University and Iraqi colleagues from the Directorates of Antiquities of Slemani and Dohuk in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq and from the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage, Baghdad. We have also benefited from the support of colleagues at the Iraq Institute for Conservation in Erbil. The work has been funded by a generous multi-year grant from Columbia University President's Global Innovation Fund for faculty. Zainab Bahrani and the team would like to convey sincere thanks to President Lee Bollinger and to Professor Safwan Masri of Columbia, as well as to colleagues at the Columbia Global Centers in Amman and Istanbul, for their staunch support of this project over the past seven years. Thanks also to the staff of the Media Center for Art History of Columbia University and to the MMM team. Versions of this paper were presented by Zainab Bahrani at Columbia University, Yale University, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Koya University. The author would like to convey her thanks to colleagues who provided valuable comments on the iconography and style of the reliefs, including Prudence Oliver Harper, Trudy Kawami, Blair Fowlkes-Childs, Michael Seymour, Vito Messina and Stefan Hauser.