INTRODUCTION

Schistosomiasis is a water-based disease caused by trematode parasites belonging to the genus Schistosoma. These worm-like invertebrates dwell in the blood stream of vertebrate hosts including human (World Health Organization, 1985; Steinmann et al. Reference Steinmann, Keiser, Bos, Tanner and Utzinger2006). Current estimates suggest that schistosomiasis affects 207 million people worldwide with 201·5 million of them living in Africa (Steinmann et al. Reference Steinmann, Keiser, Bos, Tanner and Utzinger2006; Utzinger et al. Reference Utzinger, Raso, Brooker, de Savigny, Tanner, Ørnbjerg, Singer and N'Goran2009). Poor water resources, sanitation, ignorance and poverty promote continued transmission of the disease in many rural and urban communities (World Health Organization, 1985, 1993, 2002; Gryseels et al. Reference Gryseels, Polman, Clerinx and Kestens2006; Mathers et al. Reference Mathers, Ezzati and Lopez2007; Hotez and Kamath, Reference Hotez and Kamath2009; Stothard et al. Reference Stothard, Chitsulo, Kristensen and Utzinger2009).

The World Health Organization considers schistosomiasis to be a neglected tropical disease (NTD) with an estimated 779 million people at risk of infection worldwide (Steinmann et al. Reference Steinmann, Keiser, Bos, Tanner and Utzinger2006; Hotez et al. Reference Hotez, Molyneux, Fenwick, Kumaresan, Sachs, Sachs and Savioli2007a; Utzinger et al. Reference Utzinger, Raso, Brooker, de Savigny, Tanner, Ørnbjerg, Singer and N'Goran2009). In several sub-Saharan African countries, the control of schistosomiasis has received support through global alliances and partnerships with United Nations (UN) agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and national governments based on preventive chemotherapy with praziquantel (World Health Organization, 2006; Hotez et al. Reference Hotez, Raff, Fenwick, Richards and Molyneux2007b). However, these control programmes do not include infants and pre-school-aged children (Stothard and Gabrielli, Reference Stothard and Gabrielli2007a; Sousa-Figueiredo et al. Reference Sousa-Figueiredo, Pleasant, Day, Betson, Rollinson, Montresor, Kazibwe, Kabatereine and Stothard2010a; Ekpo et al. Reference Ekpo, Alabi, Oluwole and Sam-Wobo2011; Stothard et al. Reference Stothard, Sousa-Figueiredo, Betson, Green, Seto, Garba, Sacko, Mutapi, Vaz Nery, Amin, Mutumba-Nakalembe, Navaratnam, Fenwick, Kabatereine, Gabrielli and Montresor2011a). With current global progress and commitment to the control of NTDs (Moran, Reference Moran2005; Moran et al. Reference Moran, Guzman, Ropars, McDonald, Jameson, Omune, Ryan and Wu2009; Initiative on Public-Private Partnerships for Health, 2009; Gates Foundation, 2010), many African nations are likely to receive support to implement national control programmes. It is necessary to bring to the fore, issues surrounding diagnosis and the treatment of infant and pre-school-aged children for these programmes to succeed (Keiser et al. Reference Keiser, Ingram and Utzinger2011; Stothard et al. Reference Stothard, Sousa-Figueiredo, Betson, Green, Seto, Garba, Sacko, Mutapi, Vaz Nery, Amin, Mutumba-Nakalembe, Navaratnam, Fenwick, Kabatereine, Gabrielli and Montresor2011a).

Here, we summarize the available information and progress made to date to deepen the understanding of the epidemiology and control of schistosomiasis in infants and pre-school-aged children (⩽6 years) in sub-Saharan Africa, placing particular emphasis on (i) morbidity in pre-school-aged children, (ii) factors associated with risk of infection and (iii) current efforts to include pre-school-aged children in preventive chemotherapy control programmes. This review highlights the current gaps in our knowledge of the interplay of factors associated with exposure of infants to contaminated water and efforts to consider this age group in control programmes (Montressor, Reference Montresor, Stoltzfus and Albonico2002; Stothard and Gabrielli, Reference Stothard and Gabrielli2007a). Finally, it discusses the implication for current control programmes and highlights the need for better diagnostic tools, pharmacokinetic studies of praziquantel use in pre-schoolers, drug formulation, and health education messages for mothers, caregivers and pre-school-aged children.

LIFE CYCLE AND MORBIDITY

Adult schistosome worms live together (male carrying the female) within the human blood stream. Schistosoma haematobium, which causes urinary schistosomiasis, is found in the venous plexus draining the urinary bladder of humans (World Health Organization, 1985). Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma japonicum, which cause intestinal schistosomiasis, are found in superior mesenteric veins draining the large intestine and the superior mesenteric veins draining the small intestine, respectively (World Health Organization, 1985). The females (size 7–20 mm; males slightly smaller) deposit eggs in the small venules of the portal and perivesical systems. The eggs are equipped with spines, moved progressively towards the lumen of the intestine (S. mansoni and S. japonicum) and the bladder and ureters (S. haematobium) and are eliminated with feces or urine, respectively (World Health Organization, 1985). The deposition of eggs clogs the venules, impeding blood flow. This bursts the veins, allowing blood and eggs to enter the intestine or urinary bladder, resulting in the characteristic symptom of blood in urine or feces (World health Organization, 1985).

The eggs eventually reach freshwater bodies, hatched into a miracidium, which penetrate a suitable freshwater snail intermediate host. Snails from the genus Bulinus, which comprises several species (Bu. globosus, Bu. truncatus, Bu. tropicus, Bu. forskalli and Bu. africanus) serve as intermediate hosts of S. haematobium. Snails from the genus Biomphalaria, comprised of several species (Bi. pfeifferi, Bi. alexandrina, Bi. hoanomphala, and Bi. sudanica), serve as intermediate hosts of S. mansoni. Within the snail intermediate host, the parasites multiply to produce infective cercariae. The cercariae burrow out of the snail body into the water system. Man acquires infection when exposed to water containing active cercariae (World Health Organization, 1985).

Pathology due to chronic infection with S. mansoni and S. japonicum include hepatic perisinusoidal egg granulomas, Symmers’ pipe-stem periportal fibrosis, portal hypertension, and occasional embolic egg granulomas in the brain or spinal cord. Pathology due to S. haematobium includes haematuria, scarring, calcification, squamous cell carcinoma and, occasional, embolic egg granulomas in the brain or spinal cord (World Health Organization, 1985).

In sub-Saharan Africa, statistics show that 70 million individuals are experiencing haematuria, 32 million with difficulty in urinating (dysuria), 18 million with bladder wall pathology, and 10 million with major hydronephrosis from infection caused by S. haematobium. Infection with S. mansoni is estimated to cause diarrhoea in 0·78 million individuals, blood in stools in 4·4 million and hepatomeagaly in 8·5 million. The mortality rate due to non-functioning kidney (from S. haematobium) and haematemesis (from S. mansoni) is 150 000 and 130 000 per year, respectively (van der Werf et al. Reference van der Werf, de Vlas, Brooker, Looman, Nagelkerke, Habbema and Engels2003).

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF SCHISTOSOMIASIS

Schistosomiasis is primarily a rural disease, affecting communities that depend on surface water sources. In such communities, their sources of water supply are polluted rivers, dams, streams, pools and ditches that are contaminated with human feces and urine, capable of supporting the growth and proliferation of snail intermediate hosts, where the parasite develops. The lack of safer methods of waste disposal and lack of understanding of the mode of transmission of the disease in many communities helps sustain contamination of the water system with urine and fecal waste. This ensures access of excreted eggs to the community water supply system (World Health Organization, 1985). People are at risk of contacting schistosomiasis because of ignorance, poverty, unhygienic practices, coupled with an unsafe water supply, which is still pervasive, in the least developed tropical countries of the world. The focal transmission of schistosomiasis makes the disease of less importance to the local authority.

Prevalence of schistosomiasis in infants and pre-school-aged children

Several studies of urinary schistosomiasis have tended to focus mainly on school-aged children, with little or no emphasis on pre-school-aged children, and where pre-school-aged children were part of the study, information about them was often subsumed (Akogun and Akogun, Reference Akogun and Akogun1996; Ofoezie et al. Reference Ofoezie, Christensen and Madsen1998). Table 1 summarizes the available studies of schistosomiasis in infant and pre-school-aged children in sub-Saharan Africa. Mafiana et al. (Reference Mafiana, Ekpo and Ojo2003) first reported infection among pre-school-aged children in settlements near Oyan dam, southwestern Nigeria. Out of the 209 pre-school children examined, 150 (71·8%) had an infection with 42·9% of them before their first birthday and 17·7% of the pre-school children had visible haematuria. Over the years, other studies from sub-Saharan Africa have been published. Within Nigeria alone, infections of infants or pre-school-aged children have been reported in several schistosomiasis endemic communities. The following studies are here included: in Adim, Cross River State, 25 of 126 pre-school-aged children examined, 19·8% were infected (Opara et al. Reference Opara, Udoidung and Ukpong2007). In Ilewo-Orile, Ogun State, 97 infections were reported out of 167 pre-chool-aged children (58·1%) examined (Ekpo et al. Reference Ekpo, Akintunde, Oluwole, Sam-Wobo and Mafiana2010) and in Obada/Korede, Ijebu East, Ogun State, 14 infections were reported from 83 pre-school-aged children (16·9%) examined (Ekpo et al. Reference Ekpo, Alabi, Oluwole and Sam-Wobo2011).

Table 1. Summary of prevalence report of schistosomiasis in infants and pre-school-aged children in sub-Saharan Africa

In Awutu-Efutu Senya district, in the Central region of Ghana, a monoclonal antibody dipstick test detected 33·0% infection from 97 children aged 2 months to 5 years, compared with 11·2% that was detected using urine microscopy (Bosompem et al. Reference Bosompem, Bentum, Otchere, Anyan, Brown, Osada, Takeo, Kojima and Ohta2004). In Falmado and Diambala communities of Niger, the prevalence of S. haematobium infection among pre-school-aged children was 50·5% and 60·5%, respectively (Garba et al. Reference Garba, Barkiré, Djibo, Lamine, Sofo, Gouvras, Bosqué-Oliva, Webster, Stothard, Utzinger and Fenwick2010). Infection with S. mansoni was 43·8% in Diambala. Mixed infection of both S. haematobium and S. mansoni among pre-school-aged children was 28·6% (Garba et al. Reference Garba, Barkiré, Djibo, Lamine, Sofo, Gouvras, Bosqué-Oliva, Webster, Stothard, Utzinger and Fenwick2010). In Sahelian rural communities of Mali, of 338 pre-school-aged children examined, 173 (51·2%) were infected with S. haematobium (Dabo et al. Reference Dabo, Badawi, Bary and Doumbo2011).

In East Africa, prevalence of 86·0% and 25·0% of S. mansoni infection in infants less than 3 years of age were observed in the villages of Bugoto and Bwondha, along the Ugandan shoreline of Lake Victoria (Odogwu et al. Reference Odogwu, Ramamurthy, Kabatereine, Kazibwe, Tukahebwa, Webster, Fenwick and Stothard2006). Similarly, 62·3% prevalence for intestinal schistosomiasis was reported along shore villages of Lakes Albert and Victoria in Uganda (Sousa-Figueiredo et al. Reference Sousa-Figueiredo, Pleasant, Day, Betson, Rollinson, Montresor, Kazibwe, Kabatereine and Stothard2010a). In Kenya, a prevalence of 14·0% was reported among 1-year-old infants out of 216 screened in Usoma community (Verani et al. Reference Verani, Abudho, Montgomery, Mwinzi, Shane, Butler, Karanja and Secor2011). However, on Zanzibar Island, Tanzania, infection with urinary schistosomiasis in infants and pre-school-aged children was rare because of lack of contact with water bodies (Sousa-Figueiredo et al. Reference Sousa-Figueiredo, Basáñez, Mgeni, Khamis, Rollinson and Stothard2008). In Zimbabwe, a prevalence of 21% was recorded from 100 pre-school children during a safety and efficacy study using praziquantel (Mutapi et al. Reference Mutapi, Rujeni, Bourke, Mitchell, Appleby, Nausch, Midzi and Mduluza2011).

These studies point to a growing body of evidence that in many endemic communities, schistosomiasis infection – contrary to previous beliefs – starts in early childhood. The presence of infection, points to the fact that infants and pre-schoolers are also at risk of infection like their older school-aged counterparts. The growing concern here is that infection in infants and pre-school-aged children may persist until the child starts school if left untreated. In preventive chemotherapy control programmes infants and pre-school-aged children are not eligible for treatment until school-aged (Stothard and Gabrielli, Reference Stothard and Gabrielli2007a; Sousa-Figueiredo et al. Reference Sousa-Figueiredo, Pleasant, Day, Betson, Rollinson, Montresor, Kazibwe, Kabatereine and Stothard2010a; Ekpo et al. Reference Ekpo, Alabi, Oluwole and Sam-Wobo2011). In some sub-Saharan African countries endemic for schistosomiasis and where treatment rates are still low or non-existent, early development of childhood morbidity can contribute to the long-term impact of clinical features and severity of infection such as in female genital schistosomiasis (Kjetland et al. Reference Kjetland, Poggensee, Helling-Giese, Richter, Sjaastad, Chitsulo, Kumwenda, Gundersen, Krantz and Feldmeier1996, Reference Kjetland, Ndholovu, Mduluza, Gomo, Gwanzura, Mason, Kurewa, Midzi, Friis and Gundersen2005). Since treatment is restricted to school-aged children, infants and pre-schoolers suffer health inequity (Montresor et al. Reference Montresor, Engels, Chitsulo, Bundy, Brooker and Savioli2001; Stothard and Gabrielli, Reference Stothard and Gabrielli2007a,b; Johansen et al. Reference Johansen, Sacko, Vennervald and Kabatereine2007; Stothard et al. Reference Stothard, Sousa-Figueiredo, Betson, Green, Seto, Garba, Sacko, Mutapi, Vaz Nery, Amin, Mutumba-Nakalembe, Navaratnam, Fenwick, Kabatereine, Gabrielli and Montresor2011a).

Factors associated with exposure of infant and pre-school-aged children to infection

Schistosoma infections are intimately linked to occupational activities in adults and recreational activities among school-aged children. For infants and pre-school-aged children, it becomes difficult to comprehend how children in this age group acquire infection, when they are supposed to stay at home or under strict observation by their mothers and caregivers. Studies on water-contact activities and risk factors for infants and pre-school-aged children are scanty. In many of the studies reported thus far, water-contact activities were investigated through questionnaires and focus discussion groups (FDGs) with guardians and caregivers and with older pre-school-aged children. These studies have pointed to the fact that mothers and caregiver expose their infants to infested water in the absence of other safer sources (Mafiana et al. Reference Mafiana, Ekpo and Ojo2003; Bosompem et al. Reference Bosompem, Bentum, Otchere, Anyan, Brown, Osada, Takeo, Kojima and Ohta2004). Mothers and caregivers have admitted taking their infants and pre-school children to bathe in the stream, while older pre-school children visit the water bodies for washing, fetching of water, bathing and swimming (Ekpo et al. Reference Ekpo, Akintunde, Oluwole, Sam-Wobo and Mafiana2010). In Niger, observation showed that 69·8% of the children accompanied their mothers to schistosomiasis transmission sites before their first birthday and that three-quarters of the mothers used water directly drawn from the schistosome-infested irrigation canals to wash their children (Garba et al. Reference Garba, Barkiré, Djibo, Lamine, Sofo, Gouvras, Bosqué-Oliva, Webster, Stothard, Utzinger and Fenwick2010). In Ghana, 29·2% of infants had direct contact with water bodies used by their mothers for domestic purposes (Bosompem et al. Reference Bosompem, Bentum, Otchere, Anyan, Brown, Osada, Takeo, Kojima and Ohta2004). The general agreement from these studies is that infants are exposed to infection by their mothers and caregivers who take them to water sources, or use infested water to bathe them, while the older pre-school children will visit the water bodies for swimming, washing, bathing and other activities. We are yet to better understand the interaction between paediatric schistosomiasis and other childhood diseases such as malaria and intestinal helminithiasis on the immune system. Little is known about childhood morbidity due to schistosomiasis (Betson et al. 2010). Clearly, more investigations are needed to provide information on these risk factors, co-infection with other pathogens and morbidity of childhood schistosomiasis, in order to develop intervention measures targeted at mothers and their pre-school-aged children.

IMPLICATION FOR CONTROL PROGRAMMES

The control of schistosomiasis is receiving growing international attention and political commitment since 2000, when the United Nations member states and 23 international organizations agreed on the 8 Millennium development goals (MDGs). The World Health Organization subsequently advocated that control of schistosomiasis contributes to the achievement of the MDGs and, in May 2001, the World Health Assembly endorsed resolution 54·19 that recommends regular de-worming of school-aged children at risk of infection (World Health Organization, 2001, 2005a, b). However, this recommendation only targets schoolchildren (6–15 year-olds) and/or adults (⩾15 years) in high-risk occupational groups such as fishermen (Sousa-Figueiredo et al. Reference Sousa-Figueiredo, Pleasant, Day, Betson, Rollinson, Montresor, Kazibwe, Kabatereine and Stothard2010a).

Inclusive dose pole for treatment of schistosomiasis in infants and pre-school-aged children

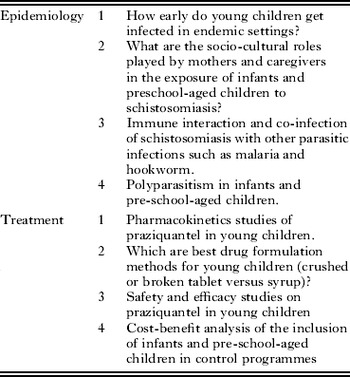

The current strategy of controlling schistosomiasis focuses on preventive chemotherapy focussing mainly on school-aged children with a single dose of praziquantel at 40 mg/kg (Hotez et al. Reference Hotez, Raff, Fenwick, Richards and Molyneux2007b). The World Health Organization considers that praziquantel is safe for humans 4 years of age and above even though the manufacturer has not explicitly stated the minimum age. Indeed, the safety of praziquantel and other anti-helmintic drugs in infants and pre-school-aged children remains to be fully characterized (Keiser et al. Reference Keiser, Ingram and Utzinger2011). The correct dosage for treatment can be determined using a dose pole (height) as against body weight in preventive chemotherapy and mass drug administration (Hall et al. Reference Hall, Nokes, Wen, Adjei, Kihamia, Mwanri, Bobrow, de Graft-Johnson and Bundy1999). The dose pole measurement has been validated to provide simple and accurate dosage between 20 and 60 mg/kg (Montresor et al. Reference Montresor, Engels, Chitsulo, Bundy, Brooker and Savioli2001, Reference Montresor, Odermatt, Muth, Iwata, Raja'a, Assis, Zulkifli, Kabatereine, Fenwick, Al-Awaidy, Allen, Engels and Savioli2005). The validity of using height for dosing in the field has been confirmed from a study in a Nigerian community (Idowu et al. Reference Idowu, Mafe, Appelt, Adewale, Adeneye, Akinwale, Manafa and Akande2007). However, the pole precludes infants and pre-school-aged children (<94 cm) from treatment. Recently, a study of the safety of praziquantel treatment in infants and pre-school-aged children in Uganda, recorded various mild reactions such as headaches (3·6%) vomiting (9·4%) diarrhoea (10·9%) and urticaria/rash (8·9%) after the first day of treatment, which ameliorated afterwards with a parasitological cure rate of 100% (Sousa-Figueiredo et al. Reference Sousa-Figueiredo, Pleasant, Day, Betson, Rollinson, Montresor, Kazibwe, Kabatereine and Stothard2010a). The study proposed a dose pole that includes infant and pre-schoolers under the height of 94 cm (Sousa-Figueiredo et al. Reference Sousa-Figueiredo, Pleasant, Day, Betson, Rollinson, Montresor, Kazibwe, Kabatereine and Stothard2010a). The assessment and approval of this modified pole will permit dosing of infants and pre-school-aged children for preventive chemotherapy (Sousa-Figueiredo et al. Reference Sousa-Figueiredo, Day, Betson, Kabatereine and Stothard2010b). Other safety and efficacy studies on infants and pre-school-aged children showed that praziquantel is safe (Mutapi et al. 2001). Nevertheless, the degree of adverse events reported by Sousa-Figueiredo et al. (Reference Sousa-Figueiredo, Pleasant, Day, Betson, Rollinson, Montresor, Kazibwe, Kabatereine and Stothard2010a) needs to be addressed through clinical trials on the safety of praziquantel in infants and pre-school-aged children. Fortunately, a recent trial conducted in Uganda among children aged 1–4 years, showed no serious adverse events for praziquantel treatment alone or in combination with mebendazole (Namwanje et al. Reference Namwanje, Kabatereine and Olsen2011). Clearly, there is a need for more in-depth studies (see Table 2) not only on safety and reduced dosage for infant and pre-school-aged children but, most importantly, pharmacokinetic (PK) studies to determine proper drug formulations, dosages and presentations to infants and pre-school-aged children in the frame of preventive chemotherapy, which we do not know (Keiser et al. Reference Keiser, Ingram and Utzinger2011).

Table 2. Research needs pertaining to schistosomiasis among infants and pre-school-aged children

Screening to include infants and pre-school-aged children for preventive chemotherapy

For infants and pre-school-aged children in sub-Saharan Africa to benefit from preventive chemotherapy, improved diagnostic methods for the screening of this age group is desirable. Several diagnostic methods to detect early childhood infection have been investigated for S. mansoni in Uganda. These include fecal occult blood and fecal calprotectin (Betson et al. Reference Betson, Sousa-Figueiredo, Rowell, Kabatereine and Stothard2010); circulating cathodic antigen (CCA), urine dipstick and stool microscopy (Midzi et al. Reference Midzi, Butterworth, Mduluza, Munyati, Deelder and van Dam2009; Stothard et al. Reference Stothard, Sousa-Figuereido, Betson, Adriko, Arinaitwe, Rowell, Besiyge and Kabatereine2011b). It has been shown that, reliance on egg detection in feces for S. mansoni diagnosis in childhood would exclude infants and pre-school-aged children receiving treatment early enough until 3–4 years later (Stothard et al. Reference Stothard, Sousa-Figuereido, Betson, Adriko, Arinaitwe, Rowell, Besiyge and Kabatereine2011b). For S. haematobium, diagnosis in childhood may require the use of the following methods: presence of microhaematuria detected by reagent strips (Mafe, Reference Mafe1997), macrohaematuria investigated by questionnaires (Red Urine Study Group, 1995; Lengeler et al. Reference Lengeler, Utzinger and Tanner2002), proteinuria detected by reagent strips (Mott et al. Reference Mott, Dixon, Osei-Tutu and England1983) or a combination of both microhaematuria and urine microscopy (Lengeler et al. Reference Lengeler, Mshinda, Morona and de Savigny1993; Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Picon, Sturrock, Sabasio, Lado, Kolaczinski and Brooker2009; Ugbomoiko et al. Reference Ugbomoiko, Dalumo, Ariza, Bezerra and Heukelbach2009a, Reference Ugbomoiko, Obiezue, Ogunniyi and Ofoezieb; Ekpo et al. Reference Ekpo, Alabi, Oluwole and Sam-Wobo2011).

Health education for mothers and caregivers

It is clear that mothers and caregivers contribute substantially to exposing their young children to Schistosoma infection. Control programmes should not rely only on preventive chemotherapy, but should also include development and utilization of health education messages targeted at mothers and caregivers (Stothard et al. Reference Stothard, Sousa-Figueiredo, Betson, Green, Seto, Garba, Sacko, Mutapi, Vaz Nery, Amin, Mutumba-Nakalembe, Navaratnam, Fenwick, Kabatereine, Gabrielli and Montresor2011a). This should be part of current control programme planning. The health education programme must be participatory to include roles for mothers and caregivers on how to avoid taking their infants and pre-school-aged children to infective water bodies (Ekpo et al. Reference Ekpo, Akintunde, Oluwole, Sam-Wobo and Mafiana2010). The usage of infective water bodies for bathing of infants and pre-school-aged children should be discouraged. The boiling of water to kill cercariae before using it to bath infants should be promoted. In addition, erection of health messages on signposts near water bodies to warn pre-school children of the dangers of schistosomiasis infection is recommended. Finally, it is noteworthy that schistosomiasis control programmes be revised to include strategies for treatment and prevention of infection in infants and pre-school-aged children. This may reduce continuous transmission of the disease in communities alongside treating school-aged and adult members of the population.

CONCLUSION

This review pertaining to schistosomiasis among infants and pre-school-aged children (⩽6 years) in sub-Saharan Africa and its implication for control has helped establish the existence of infection in children in this age group who are vulnerable, yet largely neglected in many schistosomiasis control programmes currently implemented. Where nothing is being done, infants and pre-school-aged children become a significant source of transmission in communities where schistosomiasis is endemic or re-infection in ongoing control programmes. The high prevalence (>50%) reported in most of the studies reviewed puts this age group at risk. It is also now evident that schistosome infection starts early in childhood in highly endemic areas. There is, therefore, a need for more research into the epidemiology and control of infants and pre-schoolers with schistosomiasis (see Table 2). The lack of focus on infant and pre-school-aged children in endemic communities as it currently stands ensures that transmission of infection continues in spite of treatment of the school-aged and adult populations.

Finally, we hope that this review will generate new interest in paediatric schistosomiasis, and that investigations in these areas will deepen our understanding of the problem and provide the best evidence-based approach to issues of inclusion of this age group in preventive chemotherapy.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

U.F.E. is supported by a junior Post-doctoral Fellowship from the European Foundation Initiative for African Research into Neglected Tropical Diseases (EFINTD), grant no: AZ:I/84003. We thank Professor Eka Braide for her critical comments on the manuscript.