The ever-present threats of terrorist attack and natural disaster have forced communities to constantly evaluate and improve their preparedness efforts. Recent national meetings and published documents have drawn attention to the importance of public health agencies and the emergency care community’s working together to effectively achieve a state of community preparedness.Reference O’Connor, Lerner and Allswede1, Reference Lerner, Billittier and O’Connor2 Historically, in many communities these agencies have functioned independently from one another and working together is a relatively new concept.

Traditional disaster response partners have included law enforcement agencies, fire departments, and emergency medical services (EMS) agencies. These traditional first responders have had long standing relationships with each other that have forced them to develop some degree of interoperability. Public health’s participation in these relationships has not been common, but without interoperability among public health and these first-responder agencies, optimal response to a major incident is unlikely.

Improved coordination between the emergency care community and public health agencies requires communities to address interjurisdictional, legal, governmental, and interdisciplinary concerns. Forging new relationships is difficult in any setting; however, successful integration in other communities may serve as a model for communities that are attempting to integrate public health and the emergency care community. The objective of this article is to describe 7 model communities that have functionally integrated public health and the emergency care community, and to provide a list of common features found in all of these communities.

METHODS

Constructed around the interrelated activities of partnership building, learning lessons from previous terrorist events, and disseminating information, the Terrorism Injuries: Information, Dissemination, and Exchange (TIIDE) Project was established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to address the need to develop and exchange information about injuries from terrorism. An important component of TIIDE is to identify highly functioning, interactive “model communities” that have established linkages between public health and emergency care.

To this end a competitive call for model communities was put out in the spring of 2005. The goal of this call was to identify “model communities” in which the relationship between the emergency care community and public health is well established and operationally functional in terms of its capacity to respond to events that may produce large numbers of injuries.

Twenty communities from across the nation submitted applications. These applications consisted of a 4-page written response to the 8 questions shown in Figure 1. Applications were reviewed by a panel of representatives from the national associations that participated in TIIDE and CDC staff. The applications were judged based on the following criteria:

FIGURE 1 Application questions answered by the model communities

• Illustrates a linkage between the emergency care community and public health

• A unique or novel system

• A system that is actually in use rather than theoretical

• Demonstrates that the system works

• Members of both public health and the emergency care community are involved

The review panel members read each application. They then discussed each application on a conference call and came to consensus on which represented model communities.

RESULTS

Seven communities were selected. Each community had successfully integrated public health and the emergency care community to improve routine operations and preparedness in their communities. A description of each of the 7 model communities can be found in Table 1. A description of the specific programs in each model community can be found online (see Appendix, Supplemental Digital Content1, which provides specific examples in the 7 selected model communities, http://links.lww.com/A214).

TABLE 1 Physical Description of the 7 Selected Model Communities

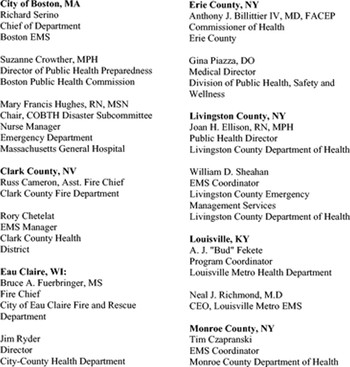

Representatives from each community were asked to attend a meeting in November 2005 at which they presented information on their communities and participated in a discussion on what was common between all of the communities. The representatives who participated in the meeting are shown in Figure 2. The objective of the meeting was to develop a list of commonalities that could be replicated across the country to improve partnerships between public health and the emergency care community. Seven elements were found to be common in each of the model communities. These elements are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 2 List of model communities and their representatives

FIGURE 3 Seven elements found to be common to all 7 model communities

DISCUSSION

All of the participants agreed that relationships were the most important factor in maintaining strong linkages between the emergency care community and public health. These relationships need to foster respect between the organizations and the people within them. To build good working relationships there is a need for both organizations to know who the players are and to have the ability to network and bring groups together. There must be a commitment to a common mission and participants need to have enough respect for each other to see each other’s strengths and enough humility to see their own weaknesses. Recognizing organizational culture and other issues, which may hinder efforts, and openly discussing them allowed the model communities to better deal with them and develop high-functioning relationships. In other words, they created a culture of cooperation between public health and the emergency care community.

A key means of accomplishing this goal was to hold face-to-face meetings on a regular basis, monthly or bimonthly. It was commonly stated that public health and emergency care community personnel should not meet for the first time at the scene of an emergency. Relationships and communication lines must have a venue in which to form and develop. Many key members of the model communities have had long-standing relationships with each other that had been in place for more than a decade. Regular meetings facilitate these existing relationships and foster new ones within the community. It was stressed that an agenda should be set for these meetings using input from all of the participants, but the planning must be flexible enough to allow groups to address the next issue that may arise. Furthermore, nontraditional participants should be considered to ensure that all of the skills that may be needed in a disaster response are represented.

Public health and the emergency care community also need to educate each other on what they do and how they function. Included in this is the establishment of everyone’s role in a disaster through disaster plans. Plans need to develop locally, accounting for unique facets of the community; it would be difficult to generalize 1 set of plans to several different communities. These plans must be fully endorsed by the group and all of the participants in the plan. The plans must be drilled on a regular basis and joint drills will help to foster linkages and better responses to actual incidents. Frequent exercises and drills strengthen and reinforce the importance of the relationships of the community leaders. Each drill and actual event should be followed with a after-action report to all of the participants that evaluates how well the plans worked and identifies any plan weaknesses. Decisions should be driven by actual data wherever possible.

Traditionally, EMS and public health have functioned independently of each another on a day-to-day basis with minimal interaction. This was not the case with our model communities. The majority of the communities have a direct line of accountability between public health and EMS. Several of the communities had an EMS office located within the public health department. In all of the communities there was either a formal reporting process between EMS and public health or a well-established communication system in which EMS and public health share information and planning. Although not a traditional structural alignment, this seems to be one of the leading factors contributing to strong linkages.

Having a crusader from the emergency care community or public health who can lead the effort and has the appropriate authority and a good leadership style will ensure that this process is successful. Furthermore, strong EMS medical direction was felt to be a contributing factor to successful linkages. Making EMS and public health part of the active medical community facilitates the information and knowledge sharing that makes strong linkages possible.

Many of the communities have educational programs that provide cross-training. The emergency care community providers are given specific public health training and likewise the public health providers are given incident command and other EMS education.

Nationally, both the emergency care community and public health are feeling financial pressure. As funding streams become more scarce, concern has been expressed that competition for funding may potentially isolate agencies. It was suggested that funding organizations take this into consideration and require cooperation between agencies. This way, linking the communities would be facilitated, rather than building individual silos due to funding constraints. All of the participants agreed that funding drives action.

CONCLUSIONS

Collaboration within communities, particularly between the emergency care community and public health, is essential for an appropriate response to a mass casualty event. The model communities described here show that this type of collaboration is possible and has resulted in a higher level of community cooperation and interaction between public health and emergency care, and has improved their planning and preparedness activities. Other communities can learn from the experiences of these model communities and strengthen their own collaborations. Specifically, communities should foster respectful working relationships between agency leaders, hold regular face-to-face meetings of those leaders, educate one another on their expertise and roles during a disaster, develop response plans together, work together on a day-to-day basis, identify and encourage a leader to facilitate these relationships, and share resources.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text; simply type the URL address into any Web browser to access this content.