Introduction

Sinonasal inverted papilloma is a benign lesion that occurs in the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. Associated clinical problems include a tendency towards local destruction, recurrence and malignant transformation into squamous cell carcinoma.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1

The medical literature contains numerous publications on sinonasal inverted papilloma, and multiple reviews have been published on different aspects of this condition. The present review comprises an amalgamation of the current literature on all aspects of the disease relevant to clinicians.

Search strategy

The Medline database was searched for published articles on ‘sinonasal inverted papilloma’. Articles on all related aspects (diagnosis, management etc) written in English and published between 1966 and July 2009 were included in the search. The medical subject headings used for the search included ‘inverting papilloma’, ‘inverted papilloma’, ‘Schneiderian papilloma’, ‘nasal’, ‘sinonasal’ and a combination of the above. Priority was given to the most current reviews, in order to reduce the conflict between the results of different reviews on a specific subject. Key articles on inverted papilloma, and papers published subsequent to the most recent reviews, were also separately evaluated.

The initial search revealed 377 articles, the abstracts of which were reviewed. Eighty-one articles were chosen for inclusion in this narrative review.

In this review, ‘inverted papilloma’ refers to the sinonasal type of the disease.

Historical perspective

In 1854, Ward was the first to document the occurrence of papilloma in the sinonasal cavity. Ringertz (1935) noted inversion of the epithelium into the underlying connective tissue, and hence the term “inverted” or “inverting” papilloma. Over the years, these tumours have been referred to by a variety of names: inverted papilloma, inverting papilloma, epithelial papilloma, sinonasal papilloma, Schneiderian papilloma and transitional cell papilloma.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1, Reference Melroy and Senior2 The term ‘inverted Schneiderian papilloma’ is suggested as an appropriate name that best conveys the qualities of inversion, location and distinctiveness of character.Reference Vrabec3

Definition

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines inverted papilloma as a benign epithelial tumour composed of well differentiated columnar or ciliated respiratory epithelium having variable squamous differentiation.Reference Shanmugaratnam and Shanmugaratnam4 The WHO classifies inverted papilloma as a subgroup of Schneiderian papillomas. The term inverted papilloma describes the histological appearance of the epithelium, i.e. inverting into the stroma, with a distinct and intact basement membrane that separates and defines the epithelial component from the underlying connective tissue stroma.Reference Mirza, Bradley, Acharya, Stacey and Jones5

Incidence and demographics

Inverted papillomas comprise 0.5 to 4 per cent of primary nasal tumours.Reference Lane and Bolger6 There is no side predilection, and bilateral cases are seen in 4.9 per cent of patients.Reference Melroy and Senior2 The male to female ratio is between 3:1 and 5:1, and patients' ages range from six to 89 years. The peak age of presentation is in the fifth and the sixth decades (average age, 53 years); however, inverted papilloma has occasionally been reported in the paediatric age group.Reference Melroy and Senior2, Reference Lane and Bolger6, Reference Krouse7 The lesion's behaviour in children appears similar to that in adults.Reference Limaye, Mirani, Kwartler and Raz8

The incidence of inverted papilloma has been reported as 0.2 to 0.7 cases per 100 000 population per year.Reference Melroy and Senior2, Reference Krouse7, Reference Buchwald, Franzmann and Tos9 The lesion's reported incidence is possibly overestimated due to selection bias, as reports are mostly from tertiary referral centres.Reference Karkos, Fyrmpas, Carrie and Swift10 The true incidence of inverted papilloma is therefore difficult to determine. The condition is most probably under-diagnosed, as it may coexist or develop alongside simple inflammatory polyps. It is possible to miss an inverted papilloma coexisting with simple inflammatory polyps, if biopsy samples collect inflammatory polyps only. For this reason, some surgeons collect all polyps for histological diagnosis, to reduce the chance of missing a concurrent inverted papilloma. It is also possible to miss an inverted papilloma developing later in the course of an inflammatory nasal polyp, if the initial histological diagnosis found the polyp to be inflammatory and no histological examination of subsequent polypectomy specimens was performed. Therefore, serial biopsies of recurrent inflammatory polyps may reduce the risk of missing a developing inverted papilloma.

Anatomical sites of presentation

The most common nasal sites involved by inverted papilloma, in order of descending prevalence, are: lateral nasal wall, ethmoid cells, maxillary sinus, and, less often, the frontal and sphenoid sinuses and nasal septum.Reference Krouse7 Inverted papilloma originating medially (i.e. from the septum or turbinates) comprises 34 per cent of reported cases; that originating laterally (i.e. from the sinuses and lateral nasal wall) makes up the rest (66 per cent).Reference Lee, Huang, Chen, Chang, Fu and Chang11 The lateral nasal wall represents the most common site of origin, whereas paranasal sinuses are quite frequently found to be involved by extension.Reference Yiotakis, Psarommatis, Manolopoulos, Ferekidis and Adamopoulos12 However, isolated sphenoid involvement with inverted papilloma has been reported in a few cases.Reference Yiotakis, Psarommatis, Manolopoulos, Ferekidis and Adamopoulos12, Reference Fakhri, Citardi, Wolfe, Batra, Prayson and Lanza13

Controversy exists over whether septal papillomas are true inverted papillomas, or whether they represent the more commonplace squamous papillomas found in the upper respiratory tract.Reference Bacon and Hendrix14

Presentation

Common presentations

Inverted papilloma patients typically present with nonspecific signs and symptoms, including unilateral nasal obstruction, nasal polyps, epistaxis, rhinorrhoea, hyposmia and frontal headache. Symptoms can be present for up to 120 months (average 72 months) before diagnosis.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1, Reference Lane and Bolger6, Reference Krouse7, Reference Kashima, Kessis, Hruban, Wu, Zinreich and Shah15, Reference Salomone, Matsuyama, Giannotti Filho, Alvarenga, Martinez Neto and Chaves16

Rare presentations

Rarely, inverted papilloma can present with diplopia, headache, meningitis, sensorineural hearing loss and tinnitus. Otalgia has been reported as a rare symptom. Tinnitus with or without hearing loss is an unusual presentation of inverted papilloma of the sphenoid sinus. Sphenoid tumours should be considered in the investigation of such symptoms. Improvement in patients' auditory symptoms has been reported after excision of sphenoid inverted papilloma; the authors of that report speculated that the increased vascularity of a sphenoid sinus inverted papilloma contributed to tinnitus.Reference Eisen, Buchmann, Litman and Kennedy17

Rare cases of inverted papilloma of the temporal bone have also been reported, both in isolation and coexisting with sinonasal inverted papilloma. The expression of progesterone receptors in some cases of temporal bone inverted papilloma may imply a certain degree of hormonal dependence.Reference Blandamura, Marioni, de Filippis, Giacomelli, Segato and Staffieri18, Reference Mazlina, Shiraz, Hazim, Amran, Zulkarnaen and Wan Muhaizan19 There are conflicting reports in the literature as to whether sinonasal and middle-ear inverted papilloma involve the same pathology, as middle-ear inverted papilloma has higher rates of recurrence and of association with squamous cell carcinoma, compared with sinonasal inverted papilloma.Reference Pou and Vrabec20, Reference de Filippis, Marioni, Tregnaghi, Marino, Gaio and Staffieri21

Aetiology

The entire Schneiderian membrane (the embryological origin of the mucous membranes of the sinonasal cavity) are at risk of developing inverted papilloma.Reference Melroy and Senior2 Molecular genetics investigations have shown that inverted papilloma is a neoplasm arising from a single progenitor cell.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1

The exact aetiology of inverted papilloma is not fully understood. However, human papilloma virus (HPV) is currently thought to be the leading cofactor in the pathogenesis of papillomas.Reference Batsakis and Suarez22, Reference Kraft, Simmen, Casas and Pfaltz23 Human papilloma virus is associated with both the inverted and exophytic types of Schneiderian papilloma, but the oncocytic type seems not to be related to HPV infection.Reference Gaffey, Frierson, Weiss, Barber, Baber and Stoler24 Human papilloma virus infection occurs in benign inverted papilloma as an early event during the multistep tumourigenesis process. Other genetic insults may be required, creating a cumulative effect, in order for inverted papilloma to progress from benign (i.e. grades I and II) through dysplastic (grade III) to carcinomatous (grade IV).Reference Kim, Yoon, Citardi, Batra and Roh25

Chronic inflammation may be involved in the pathogenesis of inverted papilloma.Reference Orlandi, Rubin, Terrell, Anzai, Bugdaj and Lanza26, Reference Papon, Lechapt-Zalcman, Abina, Abd-al-Sama, Peynègre and Escudier27 Unilateral inverted papilloma is associated with contralateral inflammation, as detected by computed tomography (CT). This degree of contralateral inflammation is greater than that seen for other sinonasal tumours.Reference Orlandi, Rubin, Terrell, Anzai, Bugdaj and Lanza26 Inflammatory cells have been identified as a significant cell population in inverted papilloma, whereas they are less commonly encountered in other types of nasal polyps.Reference Roh, Procop, Batra, Citardi and Lanza28 A histological review even suggested inverted papilloma to be an inflammatory polyp rather than a true papilloma.Reference Orlandi, Rubin, Terrell, Anzai, Bugdaj and Lanza26 Nevertheless, the exact cause–effect relationship between inflammation and inverted papilloma is still unclear.

Tobacco has been associated with inverted papilloma but the causal relationship is unproven. Occupational exposure to different types of smoke, dust and aerosol has also been speculated to have an effect.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1

Epstein–Barr virus is no longer considered to be a significant factor in the development of sinonasal inverted papilloma.Reference Gaffey, Frierson, Weiss, Barber, Baber and Stoler24, Reference Dunn, Clark, Cannon and Min29

Histology

The ectodermally derived Schneiderian mucosa gives rise to an extremely varied collection of benign and malignant neoplasms. Prototypical of these are the Schneiderian papillomas (divided into three subtypes: inverted, fungiform, and columnar or cylindrical cell) and their malignant counterparts.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1, Reference Melroy and Senior2, Reference Batsakis and Suarez22 The WHO classifies Schneiderian papillomas into three histological subtypes: inverted, exophytic and oncocytic.Reference Barnes, Tse, Hunt, Barnes, Eveson and Reichert30 The terms ‘exophytic’ and ‘oncocytic’ have been proposed by the WHO to replace ‘fungiform’ and ‘columnar or cylindrical’, respectively.

Histological examination of inverted papilloma shows epithelium inverting into the stroma, with a distinct and intact basement membrane that separates and defines the epithelial component from the underlying connective tissue stroma.Reference Mirza, Bradley, Acharya, Stacey and Jones5 The characteristic histological feature of inverted papilloma is the increase in thickness of the covering epithelium, with extensive invasion of this hyperplastic epithelium into the underlying stroma.Reference Vrabec3 The epithelium of inverted papilloma is distinct from respiratory mucosa, and lacks mucus-secreting cells and eosinophils.Reference Melroy and Senior2

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of sinonasal inverted papilloma is suspected from the clinical history, physical examination (including endoscopic nasal examination) and imaging (i.e. CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)). Macroscopically, inverted papilloma has a mulberry-like, uneven surface and a livid grey colour.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1, Reference Salomone, Matsuyama, Giannotti Filho, Alvarenga, Martinez Neto and Chaves16 Diagnosis is established through polyp biopsy and histological examination. Thorough removal of all diseased mucosa and a meticulous histological examination of the entire specimen are necessary to ensure correct diagnosis.Reference von Buchwald and Bradley31

Imaging

Computed tomography and MRI are the two main radiological modalities used in the diagnosis of inverted papilloma. The suitability of positron emission tomography (PET) scanning is under investigation.

Computed tomography

The CT findings for inverted papilloma are similar to those for inflammatory polyps.Reference Lane and Bolger6 The hallmark of inverted papilloma on CT is the unilateral opacification of a contiguous nasal cavity and sinus mass. Lobulated margins are another CT indicator.Reference Maroldi, Farina, Palvarini, Lombardi, Tomenzoli and Nicolai32 The inverted papilloma is homogeneous with a soft tissue density and enhances heterogeneously with contrast.Reference Woodruff and Vrabec33

As the tumour enlarges, the adjacent bone may become thinned, bowed, eroded or sclerotic. Bone remodelling is observed most commonly at the medial wall of the maxillary sinus, followed by the lamina papyracea.Reference Melroy and Senior2 The nasal septum is preserved until late in the disease course.Reference Woodruff and Vrabec33 Entrapped or remodelled bone can appear inside the tumour as calcifications.Reference Lane and Bolger6

Computed tomography signs of underlying bone involvement include mixed hyper- or hypodensity and bony thickening.Reference Chiu, Jackman, Antunes, Feldman and Palmer34 When evaluating a CT for focal hyperostosis, two patterns of localised bone thickening are noted: (1) ‘plaque-like bone thickening’, seen mainly when focal hyperostosis involves the lateral wall of the nasal cavity; and (2) ‘cone-shaped bone thickening’, seen only in the walls of the paranasal sinuses or the bony septum.Reference Lee, Chung, Dhong, Kim, Kim and Bok35 There is a high correlation between the origin of the inverted papilloma and the presence of focal hyperostosis on the pre-operative CT; this may facilitate pre-operative prediction of tumour origin.Reference Lee, Chung, Dhong, Kim, Kim and Bok35–Reference Sham, King, van Hasselt and Tong37

Magnetic resonance imaging

There is no signature MRI appearance for benign inverted papilloma. The main utility of MRI is in defining the extent of the lesion and differentiating inverted papilloma from inspissated mucus.Reference Melroy and Senior2, Reference Yousem, Fellows, Kennedy, Bolger, Kashima and Zinreich38 Magnetic resonance imaging is ideal for assessment of intra-cranial and intra-orbital tumour extension.Reference Lane and Bolger6 Early osteitic changes appear hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images.Reference Chiu, Jackman, Antunes, Feldman and Palmer34 Pre-operative staging of inverted papilloma by MRI is useful for planning an appropriate surgical approach.Reference Oikawa, Furuta, Oridate, Nagahashi, Homma and Ryu39

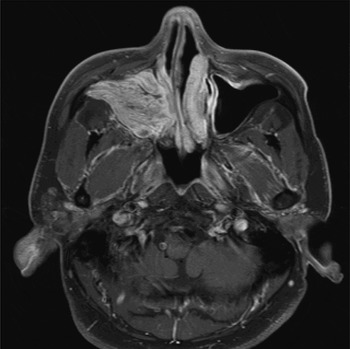

A diagnosis of inverted papilloma is suggested by a sinonasal mass located in the maxillary sinus or middle meatus, with a ‘convoluted cerebriform pattern’ on T2-weighted or enhanced T1-weighted MRI. Other authors have referred to this pattern as ‘septate striated appearance’ or ‘columnar pattern’.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1, Reference Maroldi, Farina, Palvarini, Lombardi, Tomenzoli and Nicolai32, Reference Ojiri, Ujita, Tada and Fukuda40 The convoluted cerebriform pattern is created by a juxtaposition of several epithelial and stromal layers within a regular columnar pattern; these layers appear as alternating hypointense and hyperintense bands on MRI (Figure 1).Reference Maroldi, Farina, Palvarini, Lombardi, Tomenzoli and Nicolai32, Reference Jeon, Kim, Chung, Dhong, Kim and Yim41

Fig. 1 Axial magnetic resonance imaging scan of a patient with a right-sided inverted papilloma, demonstrating a cerebriform convoluted pattern in the maxillary sinus.

Imaging and recurrence

Both primary and recurrent inverted papilloma demonstrate a similar appearance, producing low to intermediate signal on T1- and T2-weighted MRI, with heterogeneous enhancement throughout the tumour post-gadolinium.Reference Roobottom, Jewell and Kabala42

Imaging and malignancy

When bone destruction is evident, associated malignancy must be considered.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1 In MRI scans, inverted papilloma exhibits a hyperintense, heterogeneous enhancement, whereas malignant tumours appear hypointense (except for highly enhancing lesions such as neuroendocrine carcinomas).Reference Maroldi, Farina, Palvarini, Lombardi, Tomenzoli and Nicolai32

The appearance of a convoluted cerebriform pattern in the absence of extended bone erosion on MRI enables confident discrimination of inverted papilloma from malignant tumour.Reference Maroldi, Farina, Palvarini, Lombardi, Tomenzoli and Nicolai32 Although the convoluted cerebriform pattern can be suggestive of inverted papilloma, it is not pathognomonic of this condition. The convoluted cerebriform pattern can also be seen in various malignant sinonasal tumours. Focal loss of the convoluted cerebriform pattern may be caused by necrosis within the mass, and hence supply a clue to the diagnosis of inverted papilloma concomitant with malignancy.Reference Ojiri, Ujita, Tada and Fukuda40, Reference Jeon, Kim, Chung, Dhong, Kim and Yim41

It has been suggested that fluorine-18 fluoro-deoxy-glucose PET could be used to indicate probable malignancy associated with inverted papilloma, as the glycolytic activity of inverted papilloma with squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is increased; however, more recent studies suggest that PET scanning cannot be used reliably to make this distinction.Reference Shojaku, Fujisaka, Yasumura, Ishida, Tsubota and Nishida43, Reference Jeon, Kim, Choi, Lee, Kim and Jeon44

Classification and staging

Staging systems for inverted papilloma were first proposed in the 1960s by Skolnick, Norris, Fechner and Alford, and were based on the tumour–node–metastasis (TNM) staging system. However, Schneider considered the TNM staging system inappropriate for benign inverted papilloma, and proposed the first radiological staging system for inverted papilloma in 1976.Reference Krouse7, Reference Skolnick, Loewy and Friedman45 Krouse also presented a staging system for inverted papilloma, and a logical approach to its treatment (Table I).Reference Krouse7, Reference Krouse46 A year later, Han et al. proposed a similar staging system for inverted papilloma (Table II).Reference Krouse46, Reference Han, Smith, Loehrl, Toohill and Smith47

Table I Krouse staging system for inverted papilloma*Reference Krouse46

*Based on endoscopic and/or computed tomography examination.

Table II Han et al. staging system for inverted papillomaReference Han, Smith, Loehrl, Toohill and Smith47

In 2005, Kamel proposed a staging system based on the extent of the surgery required for complete endoscopic excision. This staging system divided tumours into two groups: (1) inverted papilloma arising from the nasal septum or lateral nasal wall; and (2) inverted papilloma arising from the maxillary sinus.

Kamel et al. suggested the appropriate treatment for the first group to be trans-nasal endoscopic resection, and for the second group trans-nasal endoscopic medial maxillectomy.Reference Kamel, Khaled and Kandil48

Although Krouse's classification is the most popular staging system, it suffers from several problems. Firstly, it was based on a small series and clinical intuition, rather than outcome data. Secondly, there is little difference in recurrence rates between Krouse stages I and II; thus, the prognostic usefulness of distinguishing these two groups is questionable. Thirdly, higher recurrence rate in Krouse stage IV is probably influenced by the inclusion of malignancy in this group, as inverted papilloma with malignancy has a higher recurrence rate.Reference Cannady, Batra, Sautter, Roh and Citardi49

Cannady et al. proposed a prognostic staging system suitable for the era of endoscopic treatment (Table III).Reference Cannady, Batra, Sautter, Roh and Citardi49 From the literature, these authors identified 445 patients with inverted papilloma treated by endoscopic resection, in 14 reports. These patients were then categorised into three groups on the basis of their recurrence rate. The following groups had statistically significant differences in their recurrence rates: group A (n = 234), inverted papilloma confined to the nasal cavity, ethmoid sinus and medial maxillary sinus (3.0 per cent recurrence rate); group B (n = 177), inverted papilloma with lateral maxillary sinus, sphenoid sinus or frontal sinus involvement (19.8 per cent recurrence rate); and group C (n = 34), inverted papilloma with extra-sinus extension (35.3 per cent recurrence rate).

Table III Cannady et al. staging system for inverted papillomaReference Cannady, Batra, Sautter, Roh and Citardi49

Inverted papilloma with malignancy should be staged according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer guidelines.

Treatment

Treatment of sinonasal inverted papilloma aims to remove the disease completely at the first attempt, and also to create post-operative anatomy which allows easy post-operative endoscopic surveillance.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1, Reference von Buchwald and Bradley31 It is very important to identify the site of attachment of the tumour pedicle in order to ensure full resection.Reference Lane and Bolger6

Several surgical options are available. The non-endoscopic, endonasal approach is obsolete nowadays. Current surgical approaches are generally divided into the endoscopic and the external. The method of choice depends on the extent of the disease, the skill of the surgeon and the technology available.Reference Busquets and Hwang50 Options comprise: (1) endoscopic, endonasal approach; (2) limited external approach (e.g. Caldwell–Luc); (3) radical external approach (e.g. medial maxillectomy via lateral rhinotomy or midfacial degloving); and (4) a combination of endoscopic and external approaches.

External approaches are used when complete resection is impossible endoscopically.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1 The intra-operative findings, most importantly the site(s) of tumour attachment, dictate whether an endoscopic procedure is sufficient to resect the inverted papilloma completely, or whether an adjunctive, external procedure is also required.Reference Wolfe, Schlosser, Bolger, Lanza and Kennedy51 Over the years, there has been a slow evolution from aggressive en bloc resection to lateral rhinotomy to endoscopic techniques.Reference Sauter, Matharu, Hörmann and Naim52 En bloc resection is not necessary to achieve oncological cure; in other words, piecemeal endoscopic excision is curative as long as the tumour has been excised fully. Relative limitations to the endoscopic method include extensive tumour, intra-cranial or orbital extension, extensive skull base erosion, extensive frontal or infra-temporal fossa involvement, and extensive scarring and anatomical distortion from previous surgery; however, advances in endoscopic skull base surgery are gradually pushing back these boundaries.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1, Reference Banhiran and Casiano53, Reference Mackle, Chambon, Garrel, Meieff and Crampette54 In inverted papilloma with associated malignancy, the external approach is the recommended method.Reference Krouse7, Reference Lawson and Patel55

Systematic analysis supports the use of endoscopic treatment of inverted papilloma. The endoscopic approach has lower complication rates, compared with the conventional, external approach, and hospital stay is significantly shortened.Reference Kim, Kim, Park, Koo, Park and Rha56 However, when comparing endoscopic and non-endoscopic methods of treatment, one should bear in mind the following issues which may artificially heighten the superiority of the endoscopic method. Firstly, most centres have not generally employed endoscopic methods for more extensive disease. Secondly, comparison of outcomes between studies is difficult due to failure to adopt a common staging system. Finally, studies reporting the results of endoscopic methods have generally had a shorter duration of follow up.

Treatment protocols

The aim of surgical treatment of sinonasal inverted papilloma is to remove the whole disease. The method of surgical treatment that offers the best operative exposure and least morbidity is dictated by the extent of the disease and the surgeon's technical ability. It is therefore advisable that high-stage inverted papilloma and complex cases (including cases associated with malignancy) are treated and managed in specialist centres, in order to reduce morbidity and recurrence rates.

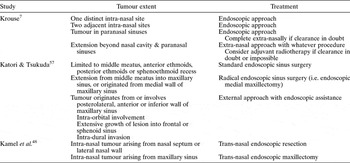

Krouse's proposed treatment protocol was based on the tumour staging described by Skolnick.Reference Krouse7 Katori and Tsukuda proposed another strategy based on categorising the extent of the disease into three groups.Reference Katori and Tsukuda57 There was no significant difference in recurrence rates between their proposed groups. Kamel et al. proposed a strategy for endoscopic surgery in which patients were divided into two groups.Reference Kamel, Khaled and Kandil48 They advocated an endoscopic technique for intra-nasal tumours, and used involvement of the maxillary sinus as the differentiating factor in determining the method of choice (Tables IV and V).

Table IV Skolnick et al. staging system for inverted papilloma*Reference Skolnick, Loewy and Friedman45

*Based on endoscopic assessment and/or computed tomography scan. T = tumour

Table V Published treatment strategies for excision of sinonasal inverted papilloma

Special surgical considerations

Excision of inverted papilloma bony attachments

The irregularity of the bony surface may hinder complete inverted papilloma removal, because microscopic rests of mucosa can be hidden within the bony crevices. Intra-operative removal of the bony surface at the site of tumour attachment may ensure complete removal. Chiu et al. recommend using a diamond burr drill to smooth out the bony surface underlying the tumour pedicle.Reference Chiu, Jackman, Antunes, Feldman and Palmer34 It remains to be seen whether removal of the bony surface underlying an inverted papilloma tumour affects its recurrence rate.

Maxillary sinus

Complete resection of the inverted papilloma bony attachment to the posterior, lateral or anterior maxillary sinus walls requires special endoscopic techniques, such as a trans-septal approach through the opposite nostril, a canine fossa puncture to introduce the debrider or the endoscope, or an endoscopic maxillectomy.Reference Wormald, Ooi, van Hasselt and Nair58 An external approach (e.g. Caldwell–Luc) may provide ideal access if the maxillary sinus is significantly involved.

Frontal sinus

Frontal sinus inverted papilloma with medial or posterior wall involvement can generally be managed by standard endoscopic frontal sinus surgery. However, tumours with multifocal involvement will require an endoscopic modified Lothrop procedure. This approach obviates the need for an osteoplastic flap in most patients with inverted papilloma of the frontal sinus, unless there is significant lateral tumour extension.Reference Zhang, Han, Wang, Ge and Zhou59, Reference Yoon, Batra, Citardi and Roh60 If the tumour attachment cannot be addressed endoscopically, then an osteoplastic flap approach is required.Reference Lane and Bolger6 A modified Lothrop procedure to address inverted papilloma of the frontal sinus is however superior to osteoplastic flap creation, as the latter hinders endoscopic surveillance of the area in the post-operative period.Reference Wormald, Ooi, van Hasselt and Nair58

Skull base

Patients with erosive skull base lesions adjacent to the internal carotid artery are best managed with a staged endoscopic resection utilising intra-operative computer-aided navigation. Pre-operative medical therapy can help normalise inflamed mucosa and minimise intra-operative bleeding.Reference Fakhri, Citardi, Wolfe, Batra, Prayson and Lanza13

Dura and periorbita

The evidence on these aspects is based purely on limited expert opinion and clinical case reports. A multidisciplinary approach is recommended if access is required via orbitotomy or craniotomy. It is advised that any tumour attached to periorbita or dura should be dealt with by bipolar electrocautery rather than by excision of the dura or periorbita, as they provide an effective barrier to tumour spread.Reference Wolfe, Schlosser, Bolger, Lanza and Kennedy51

Radiotherapy

Although some authors have used radiotherapy in cases in which the tumour was inoperable or complete resection impossible, generally this modality is used as an adjunct when inverted papilloma is associated with malignancy.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1, Reference Mendenhall, Hinerman, Malyapa, Werning, Amdur and Villaret61

Treatment of associated malignancy

Inverted papilloma with dysplasia should be treated in the same way as benign disease.Reference Mirza, Bradley, Acharya, Stacey and Jones5 However, treatment of inverted papilloma associated with SCC consists of radical surgery and post-operative radiotherapy.Reference Mirza, Bradley, Acharya, Stacey and Jones5 Krouse advocates lateral rhinotomy and medial maxillectomy as the ideal surgical approach in any malignant case.Reference Krouse7

Recurrence

Most recurrence occurs early within the first two to three years after initial treatment (mean, 30 months; range, 14–48 months), although a small percentage of cases have been seen five to six years post-operatively.Reference Busquets and Hwang50, Reference Mackle, Chambon, Garrel, Meieff and Crampette54 Most recurrence occurs at the site of the original tumour, strongly suggesting incomplete local resection (i.e. residual disease) as the main cause of recurrence.Reference Karkos, Fyrmpas, Carrie and Swift10, Reference Wormald, Ooi, van Hasselt and Nair58

The likelihood of local recurrence after inverted papilloma resection varies. It can be as high as 100 per cent for non-endoscopic, endonasal approaches; however, on average it ranges from 5 to 50 per cent, depending on the extent of the disease and the resection.Reference Busquets and Hwang50, Reference Mendenhall, Hinerman, Malyapa, Werning, Amdur and Villaret61 The average recurrence rate is 13 per cent for endoscopic procedures, as high as 34–58 per cent for limited endonasal procedures, and 14–17 per cent for lateral rhinotomy with medial maxillectomy.Reference Mirza, Bradley, Acharya, Stacey and Jones5, Reference Karkos, Fyrmpas, Carrie and Swift10 In general, recurrence rates are lower for primary resections compared with secondary resections, regardless of the surgical approach.Reference Han, Smith, Loehrl, Toohill and Smith47 Less aggressive approaches to the sinuses, and non-endoscopic intra-nasal procedures (such as the isolated Caldwell–Luc procedure), have unacceptable recurrence rates and should be abandoned.Reference Krouse7

Although some studies found no association between the recurrence rate and the aggressiveness of surgical treatment, some have shown the recurrence rate to be directly linked to the extent of the definitive procedure. Busquets and Hwang undertook a review of endoscopic resection of sinonasal inverted papilloma, and could not establish a relationship between advanced tumour stage and raised incidence of recurrence in some of their reviewed articles. However, this may have been due to their failure to analyse their cohort according to disease stage, owing to lack of staging data in the reviewed literature.Reference Busquets and Hwang50 Another review of the literature, involving studies published from 1985 to 2006 which provided Krouse staging, did find a relationship between inverted papilloma recurrence rate following endoscopic approach and Krouse T stage, as follows: T1 = 0 per cent, T2 = 4 per cent, T3 = 19.2 per cent and T4 = 35.3 per cent.Reference Cannady, Batra, Sautter, Roh and Citardi49 A systematic review of the literature supports endoscopic resection as a favourable treatment option for most cases of sinonasal inverted papilloma, with no significant difference observed between the endoscopic and the external approaches.Reference Han, Smith, Loehrl, Toohill and Smith47, Reference Busquets and Hwang50, Reference Sauter, Matharu, Hörmann and Naim52

As previously noted, review articles on different surgical methods have published a wide range of recurrence rates. To enable reliable comparison between different techniques, certain aspects should be taken into consideration, as follows.

Follow up

When comparing different methods, the follow-up period should be more or less the same. The endoscopic approach is a much newer technique; hence, the reviewed articles reported a shorter follow-up period for this technique compared with more conventional methods.

Surgical technique

The effects of the learning curve required for any new technique (e.g. endoscopic treatment of extensive disease) should be taken into account when considering the higher recurrence rates reported for the endoscopic approach in early papers. The surgeon's technical ability has a great influence on the outcome; some centres clearly produce better results than others.

Tumour staging

The endoscopic approach has generally been employed for less extensive tumours. Despite the inherent advantages of endoscopic resection of inverted papilloma, critics have suggested that confounding case selection bias and ‘stage drift’ have produced misleading results that incorrectly favour the endoscopic approach.Reference Cannady, Batra, Sautter, Roh and Citardi49

Clinical predictors of recurrence

There are no robust clinical prognostic factors determining who is at risk of developing recurrent inverting papilloma.Reference Karkos, Fyrmpas, Carrie and Swift10 However, Jardine et al. found that patients who smoked showed a trend towards multiple recurrences.Reference Jardine, Davies and Birchall62 In addition, patients with a frontal sinus inverted papilloma have been shown to be more prone to multiple recurrences.Reference Katori, Nozawa and Tsukuda63 This might be due to the technical difficulties of undertaking complete endoscopic resection in this anatomical area.

Histological predictors of recurrence

There are no pathognomonic histological features to predict the recurrence of inverted papilloma. However, there are certain histopathological parameters that raise suspicion of recurrence. Multiple recurrences (without malignancy) are related to an increase in hyperkeratosis, the presence of squamous epithelial hyperplasia, an increase in mitotic index (i.e. to more than two mitoses per high power field) and an absence of inflammatory polyps.Reference Batsakis and Suarez22, Reference Wormald, Ooi, van Hasselt and Nair58, Reference Katori, Nozawa and Tsukuda63, Reference Nielson, Buchwald, Nielson and Tos64

Markers for recurrence

There is an ongoing search for markers for inverted papilloma recurrence. Although no definite and reliable marker has yet been found, increased proliferative activity (reflected by Ki67 levels), loss of basal cell keratin 14 expression and high levels of proliferating cell nuclear antigen on immunohistochemical staining of an inverted papilloma specimen can be suggestive of recurrence.Reference Mumbuc, Karakok, Baglam, Karatas, Durucu and Kibar65–Reference Gunia, Liebe and Koch67 Serum SCC antigen levels can be used as a marker for recurrence; the marker level decreases after surgical resection of inverted papilloma.Reference Yasumatsu, Nakashima, Kuratomi, Hirakawa, Azuma and Tomita68, Reference Yasumatsu, Nakashima, Masuda, Kuratomi, Shiratsuchi and Hirakawa69 Fascin is usually expressed at a low level in normal epithelium, but it is significantly increased in benign inverted papilloma. Serial measuring of this protein can be used as a marker for inverted papilloma recurrence.Reference Wang, Liu and Zhang70

Malignancy

The predominant malignancy associated with inverted papilloma is synchronous or metachronous SCC, although verrucous carcinoma and adenocarcinoma have also been reported.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1

Malignancy can either coexist with inverted papilloma at the time of diagnosis (i.e. synchronous) or develop later at the site of previous resection (i.e. metachronous).Reference Karkos, Fyrmpas, Carrie and Swift10 In the literature, associated malignancy is reported to be 7 per cent synchronous and 3.6 per cent metachronous, although rates may be exaggerated due to a referral bias to tertiary centres.Reference Mirza, Bradley, Acharya, Stacey and Jones5 A more recent study found that five out of six malignancies were synchronous.Reference Tanvetyanon, Qin, Padhya, Kapoor, McCaffrey and Trotti71 The difference may be due to better and wider sampling and more thorough histological examination. Some authors advocate using a suction trap and collecting the entire excised or debrided specimen for histological examination.Reference Wormald, Ooi, van Hasselt and Nair58

The considerable variation in the incidence of associated malignancy (from less than 1 per cent to 53 per cent in some reports) results from differing follow-up periods and cohort sizes.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1, Reference Batsakis and Suarez22, Reference Busquets and Hwang50, Reference Mendenhall, Hinerman, Malyapa, Werning, Amdur and Villaret61, Reference Tanvetyanon, Qin, Padhya, Kapoor, McCaffrey and Trotti71 The incidence of malignancy may be lower than reported in the literature, as reported patients have mostly been treated in tertiary referral centres. In fact, inverted papilloma cases diagnosed in a non-tertiary centre were more benign than previously reported.Reference Jardine, Davies and Birchall62 Some authors distinguish between ‘concurrent inverted papilloma and SCC’ and ‘inverted papilloma progressing into SCC’. The actual rate of inverted papilloma malignant transformation (i.e. progression) is very low (1–2 per cent) if cases of concurrence are eliminated.Reference Krouse7, Reference Karkos, Fyrmpas, Carrie and Swift10

The mean time taken to develop a metachronous carcinoma is 52 months (range, six to 180 months). However, such tumours can develop after a prolonged period of time. The median overall patient survival time is 126 months, with a five-year survival rate of 61 per cent. Although the survival outcome of patients with SCC arising from inverted papilloma seems comparable to that for primary sinonasal SCC, some patients with this disease do have highly aggressive malignancy, including haematogenous distant metastasis. Overall, about 40 per cent of patients will die of the disease within the first three years.Reference Tanvetyanon, Qin, Padhya, Kapoor, McCaffrey and Trotti71

Inverted papilloma patients with malignancy are generally older than those without.Reference Katori, Nozawa and Tsukuda72 However, a retrospective study of 197 patients with inverted papilloma, compared with 1583 patients with inflammatory nasal polyps, showed a similar distribution by age and sex. All instances of head and neck carcinoma diagnosed in both cohorts over a 38-year calendar period revealed inverted papilloma to be associated with an increase in non-sinonasal head and neck carcinoma (tobacco may be a causative link).Reference Dictor and Johnson73

Aetiology of malignant transformation

In cases of inverted papilloma, the cause of carcinoma development has not yet been identified. Elevated levels of epithelial growth factor receptor and tumour growth factor α (TGF-α) have been found in precancerous inverted papilloma lesions.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1, Reference Sauter, Matharu, Hörmann and Naim52 Mutation of the p53 tumour suppressor gene has been named as a risk factor for malignant transformation.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1 However, it has been suggested that p53 may not be directly involved in the apoptotic regulatory pathway in inverted papilloma, as it does not show a positive association with the apoptotic rate (inverted papilloma contains a higher mean number of apoptotic bodies compared with normal surrounding sinonasal tissue).Reference Mirza, Nofsinger, Kroger, Sato, Furth and Montone74 Significantly increased staining of p21 and p53 has been observed in ‘inverted papilloma with severe dysplasia’, ‘inverted papilloma with carcinoma’ and ‘inverted papilloma with invasive carcinoma’, compared with healthy nasal mucosa.Reference Katori, Nozawat and Tsukuda75 A possible link to HPV positivity has also been postulated.Reference Katori, Nozawa and Tsukuda72 A significant increase in dysplasia has been observed in inverted papilloma in the HPV 6/11- and 16/18-positive groups.Reference Katori, Nozawat and Tsukuda75

Inverted papillomas are monoclonal proliferations, yet they do not fit the profile of a prototypical precursor lesion. Unlike squamous epithelial dysplasia, inverted papilloma does not routinely harbour several of the key genetic alterations that are associated with malignant transformation of the upper respiratory tract.Reference Califano, Koch, Sidransky and Westra76

Recurrent inverted papilloma does not seem to be related to the development of malignancy.Reference Wormald, Ooi, van Hasselt and Nair58

Histological predictors of malignancy

Certain histopathological parameters raise suspicion of the development of SCC in inverted papilloma. Malignancy is related to the presence of bone invasion, absence of inflammatory polyps, increased ratio of neoplastic epithelium to stroma, increased hyperkeratosis, presence of squamous epithelial hyperplasia, high mitotic index, low number of eosinophils and the presence of plasma cells.Reference Sauter, Matharu, Hörmann and Naim52, Reference Katori, Nozawa and Tsukuda63

Predictor markers for malignancy

There is evidence that the presence of HPV in inverted papilloma could be predictive of malignant transformation.Reference Sauter, Matharu, Hörmann and Naim52, Reference Mendenhall, Hinerman, Malyapa, Werning, Amdur and Villaret61, Reference McKay, Grégoire, Lonardo, Reidy, Mathog and Lancaster77 Over-expression of p53 may serve as a marker for malignant transformation of inverted papilloma.Reference Mendenhall, Hinerman, Malyapa, Werning, Amdur and Villaret61, Reference Bura, Seiwerth, Vladika, Perović, Nagy and Corić66, Reference Gujrathi, Pathak, Freeman and Asa78 Screening inverted papilloma patients for p21 may also identify those at risk of developing dysplasia or SCC.Reference Mendenhall, Hinerman, Malyapa, Werning, Amdur and Villaret61 In inverted papilloma cases associated with malignancy, an inverse relationship has been found between HPV and p53 over-expression (i.e. p53 over-expression was seen in the majority of HPV-negative cases).Reference Buchwald, Lindeberg, Pedersen and Franzmann79

In inverted papilloma cases, a significant correlation is seen between topoisomerase II-α and Ki67 expression, indicating that these could be independent prognostic factors for possible malignant transformation.Reference Bura, Seiwerth, Vladika, Perović, Nagy and Corić66, Reference Hadar, Shvero, Yaniv, Shvili, Leabu and Koren80 Fascin, an actin-binding protein, is usually expressed at a low level in normal epithelium, but its expression is significantly increased in benign inverted papilloma, and greatly increased in associated malignancy. Serial measurement of this marker can be used as a marker for malignancy.Reference Wang, Liu and Zhang70 Increased expression of epithelial growth factor receptor and TGF-α is associated with early events in inverted papilloma carcinogenesis.Reference Sauter, Matharu, Hörmann and Naim52 Positive immunostaining for epithelial growth factor receptor protein is significantly increased in inverted papilloma, ‘synchronous carcinoma with inverted papilloma’ and ‘metachronous carcinoma with inverted papilloma’, compared with inflammatory polyps and normal mucosa. This suggests a role for epithelial growth factor receptor in the malignant transformation of inverted papilloma to SCC of the nasal cavity.Reference Chao and Fang81

Follow up

Recurrent inverted papilloma and metachronous carcinoma can develop after a prolonged period of time. Long-term follow up is recommended to detect recurrence, as disease can become extensive before it becomes symptomatic.Reference Mirza, Bradley, Acharya, Stacey and Jones5 Some authors advocate life-long follow up of inverted papilloma patients.Reference von Buchwald and Bradley31

Hyperkeratosis, squamous epithelial hyperplasia and a high mitotic index are negative prognostic indicators which may be useful in the future follow up of patients with inverted papilloma.Reference Sauter, Matharu, Hörmann and Naim52

If recurrence is suspected, biopsy of the polyps and/or cross-sectional imaging is required. Magnetic resonance imaging with contrast is used to differentiate tumour from post-operative changes and inflammatory polyps; it can also guide the surgeon to the optimum sites for biopsy.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1

Prognosis

A variety of factors have been suggested to have an impact on the prognosis of patients with inverted papilloma.

Tumour size

Larger tumours have been shown to have higher recurrence rates. However, this may in fact be due to incomplete removal of the disease (i.e. to residual disease).Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1

Human papilloma virus

Some findings suggest that HPV types 16 and 18 may be more associated with malignancy in inverted papilloma cases, whereas HPV types 6 and 11 are more related to benign pathology.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1

Histology

There is no reliable prognostic parameter for inverted papilloma recurrence or malignant transformation. However, increased hyperkeratosis, squamous epithelial hyperplasia, increased mitotic index and the absence of inflammatory polyps have all been shown to be related to inverted papilloma recurrence.Reference Eggers, Mühling and Hassfeld1, Reference Batsakis and Suarez22, Reference Katori, Nozawa and Tsukuda63

Conclusion

Sinonasal inverted papilloma is a benign tumour which mostly presents with symptoms owing to unilateral nasal polyposis. It has a tendency to recur, and also carries the risk of malignant transformation. Diagnosis is confirmed by histology but may require CT or MRI to assess accurately the extent of the disease. The treatment of choice is complete surgical removal via an endoscopic approach, assisted with an external approach if complete resection is not possible endoscopically. Currently, no histological or biological markers can accurately and reliably predict the risk of recurrence or malignant transformation. Long-term follow up is indicated, although the majority of recurrent cases present within the first two to three years after initial treatment.