Protean Power Footnote 1 is a critically important book of the kind that comes along once in a generation, and which therefore must be read and reread by all students of world politics and domestic politics. This is both because of what it says and what it does not say (explicitly). By the latter, I mean the ‘unspoken’ meta-theoretical assumptions about social reality and our knowledge of it, as well as their implications to our understanding of political power broadly conceived. By choosing to mostly sidestep the meta-theoretical assumptions underlying protean power, Peter Katzenstein and Lucia Seybert (Katzenstein's untimely deceased co-author) appeal to a much larger audience; it was the right move. The question is, however, where do we go from here? This is because the ‘unspoken’ assumptions also apply to how we should understand international systems, international order, global governance, international institutions and practices, war and peace, social change, normative change, and much more. Do we redefine each of these concepts separately until the overall gestalt becomes apparent? Or do we say, let us not beat around the bush and be clear: except for under narrow and temporary conditions, humans cannot control events, even though they may believe they can. This makes control power a special case of protean power. The reason for this is not only that our knowledge of the world is usually partial – if only because, unlike amoebas, human beings can always surprise us – but primarily because uncertainty is a property of the world. Thus, if political science is mature enough to reconsider its disciplinary practicesFootnote 2 we should waste no time and begin to rethink our ‘unspoken’ assumptions.

This is what I will attempt to do in the following text by asking how we should conceive power and politics in a radically uncertain worldFootnote 3 – again, not only because of our partial knowledge of the world, but primarily because of its emergent nature. More specifically, I will make the following arguments (not necessarily in this order):

(1) Political agents' experience of control is an illusion. Even at those rare occasions when agents use ‘control power’ and get close to fully controlling events, control power remains a special case of protean power.

(2) Because the world is physically and socially indeterminate regardless of our (lack of) knowledge,Footnote 4 I agree with Reus-Smit that all ‘operational uncertainty’ is really ‘radical uncertainty’.Footnote 5

(3) All agents are ‘agile’. Innovation is a property of agency; in other words, even ‘rigid’ agents can be creative.Footnote 6 As Colapietro notes, ‘the very terms of identification and description … cannot be defined either in advance of the process …or apart from the process of ongoing activity’.Footnote 7

(4) Agents act driven not only by dispositions based on experience but also by expectations of the future. Although in their concluding chapter Katzenstein and Seybert discuss expectations and imagination, in their key Figure 1.1 on p. 13 expectations play second fiddle to dispositions.

(5) Because agents and structures congeal or collapse, namely, they become entities via social practices,Footnote 8 we cannot easily distinguish between power and practices, as Katzenstein and Seybert do. Protean power operates through practices and practices require protean power.

(6) The litmus test for making protean power and consequently revised ontological and epistemological assumptions a guide for our explanations and research is whether they can help us explain world politics more accurately, albeit less predictably, than the alternatives. By politics, I mean processes by which agents actualize or ‘freeze’ real propensities through political action and practices. By knowledge of politics, I mean explaining these processes.

(7) The above arguments do not mean having to stop searching for factual knowledge via empirical research and experiments. We should bear in mind, however, that although empirical research and experiments aimed at predicting events may produce successful stable statistical findings, this is because we base our experiments on static ontologies, mostly closed systems, and on equilibrium and rationality assumptions. Taking an evolutionary epistemological approach instead and tracing the flow of events through which processes unfold,Footnote 9 may help us guide our research on a protean power world.

(8) Following from the above, I will suggest a revision to Katzenstein and Seybert's Figure 1.1 and illustrate very briefly the revised parameters and practices by discussing Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Bio Engineering's challenges to humanity.Footnote 10

Illusion of control and radical uncertainty

The crucial difference between Katzenstein and Seybert's approach in Protean Power and mine is that to them ‘the distinction between control power and protean power rests on the underlying assumptions about knowledgeability of the world’,Footnote 11 namely that the problem of uncertainty is mainly epistemological. In a protean power world epistemological uncertainty reigns and risk becomes very difficult if not impossible to discern because probabilities are incalculable. Building on Karl Popper, I argue, however, that the problem of uncertainty is not merely epistemological but primarily ontological, owing to the indeterminate condition of the natural and social worlds. According to the received view of quantum theory (the so-called ‘Copenhagen Interpretation’), probabilities have to do with our state of mind, a subjectivist theory of probabilities. But Popper argued that the world would be just as indeterminate even if there were no observing subjects to experiment or interfere with it.Footnote 12 Quite apart from the fact that ‘we do not know the future’, according to Popper, ‘the future is objectively not fixed. The future is open: objectively open’.Footnote 13 In accordance with his indeterminism assumption, Popper suggested a theory of objective indeterminacies or propensity theory, where there ‘exist weighted possibilities which are more than mere possibilities, but tendencies or propensities … to realize themselves which are inherent in all possibilities’.Footnote 14

Propensities, as with Aristotle's ‘potentials’, are about the dispositional processes of turning potential into actuality.Footnote 15 Unlike Aristotle, however, Popper argued that potential is inherent not in physical objects, including humans, but in the relational nature of unfolding situations, or becoming, in what people practice and do, or not do, choose or not choose to do.Footnote 16 The realization of propensities then depends on the contestation of complementary or opposing tendencies which ‘resemble forces, or fields of forces … Force, like propensity, is a relational concept’.Footnote 17 Protean power, thus, is about ‘propensities for setting bodies in motion’.Footnote 18 The fall of the Berlin Wall, which Katzenstein and Seybert use to illustrate uncertainty, shows that the event was not only unpredictable due to epistemological uncertainty, but also that it may not have happened at all. If potential is grounded not only in subjective knowledge but also in performativity and how a relational situation unfolds, protean power should be considered not only as affecting practices, but also as being inherent in practices, in action and transactions.

Popper theorizes that propensities can be described as ranging from 0 (no propensity for something happening) to 1 (the special case according to which a cause produces an effect).Footnote 19 Causation, therefore, is a special case of propensity.Footnote 20 Popper adds, however, that in ‘our real changing world … propensities[,] change all the time. They certainly may change if we, or any other organisms, prefer one possibility to another; or if we discover a possibility where we have not seen one before. Our very understanding of the world changes the conditions of the changing world; and so do our wishes, our preferences, our motivations, our hopes, our dreams, our phantasies, our hypotheses, our theories. Even our erroneous theories change the world …’.Footnote 21

Popper's propensity theory is grounded in challenges to an ontologically deterministic view of nature and the social world. These challenges follow Charles Darwin's evolutionary theory, the formulation of quantum theory by Max Planck, and the theory of relativity by Albert Einstein.Footnote 22 Quantum theory, for instance, brought about ‘the dematerialization of physical matter’. ‘Instead of very small things (atoms) combining to produce standard processes (avalanches, snowstorms) physics seemed to suggest that very small processes (quantum phenomena) combine to produce standard things (ordinary macro-objects) …’.Footnote 23 Time and irreversibility, in turn, acquired new urgency because of relativity theory.Footnote 24

Unlike Alexander Wendt, who most prominently among IR scholars is increasingly explaining social action as resulting from quantum phenomena,Footnote 25 I believe that social relational and process ontologies (they are not the same, but for the sake of this essay we can say that they complement each other) best capture the indeterminate nature of our social world, without the need to naturalize social processes. Process ontology, whose origins can be traced to pre-Socratic times, and relational ontology benefitted from evolutionary theory and the new physics.Footnote 26 American pragmatists such as Charles S. Peirce, John Dewey, William James, and G.H. Mead came to terms with their implications for social theory. Dewey, for example, laid the foundations for understanding social reality as relational by arguing that meaning is an aspect of cooperative behavior that arises in people's ‘transactions’. Although ‘interaction’ assumes internal essences and a separate existence of physical entities, ‘transaction’ means that as people come into contact ‘the components themselves are subject to change. Their character affects and is affected by the transaction’.Footnote 27 A relational and processual ontological perspective, therefore, does not reject the existence of substances; it rather takes them as instantiations of relations and processes.Footnote 28

Affected by the development of quantum physics, in turn, Whitehead abandoned the notion that ‘matter and hence causal mechanisms are assumed to be simply locatable at specific coordinate points in space-time’.Footnote 29 Instead, he described the world as dynamic processes in which in ‘the becoming of an actual entity, the potential unity of many entities in disjunctive diversity – actual and non-actual – acquires the real unity of the one actual entity’.Footnote 30

More recently, complexity theory's concepts, such as ‘self-organization’, ‘emergence’, and ‘order through fluctuations’,Footnote 31 support the notion of a socially emergent or ‘becoming’ ontology.Footnote 32 Most striking are Nobel Prize winner Ilya Prigogine's theories of non-equilibrium thermodynamics, which highlight time irreversibility and the self-organization of evolving systems in the face of permanent instabilities and fluctuations under a threshold. When a system in a state of disequilibrium approaches a threshold, it may either tip, change into a new order, or remain meta-stable, albeit highly volatile. Whether a system tips or not, however, is not only unpredictable but also indeterminate.Footnote 33 The fall of the Berlin Wall is an excellent case of a social system that, upon approaching a threshold, might as well have not tipped and evolved, although it did, prompting the end of the Cold War.

It follows, thus, that people take risks under the illusion of control. One of the fallacies leading to the illusion of control lies in understanding subjective experiences as being ‘pushed’ (determined) primarily by past-lived occurrences. Rather, due to the relational, processual, and contingent nature of social reality, past experiences only ‘determine changing propensities that influence future situations without determining them in a unique way’.Footnote 34 Thus, the past is seldom a good guide for the future. Moreover, subjective experiences are also pulled toward the future by expectations, namely theories of the future that need to be constantly revised. Katzenstein and Seybert are aware of the importance of expectations for protean power, but they focus primarily on their failure due to partial knowledge. Expectations can, however, yield indeterminacy and uncertainty regardless of whether individuals possess or lack complete knowledge. This may happen, for example, via self-fulfilling prophecies and self-defeating prophecies, which are due not only to partial knowledge, but also to socially relational and collective actions. Because individuals collectively construct social reality with their expectations, they make actions uncertain and unpredictable.

Radical uncertainty also rests on agents' capacity to persuade audiences, on what Jeffrey Alexander called ‘performative power’.Footnote 35 Turning propensities into realization depends on the way agents ‘act’ (as in a theater) in the world and whether and how they are able to persuade (or not) their audiences, which can be as small as a press conference (as in the afternoon of 9 November 1989) or as large as world public opinion. US President Trump, for example, possesses a great deal of performative power with his own base. Yet, although Trump's may control his base, albeit temporarily, he cannot control events. Because of his actions and lies, Trump generates opposition forces, contestation, and learning processes, which together generate more uncertainty and protean power aimed at ending his presidency.

Following the arguments above, how do we then explain that throughout history agents using superior coercive material power and social power, such as legitimate authority, were able to control other agents' actions, thus causally affecting events? First, as Popper argued, control takes place only when competing forces are absent or were eliminated and propensities for something happening become equal to 1.Footnote 36 Second, even when propensities become equal to 1, due to the emerging and changing nature of the social world, they are likely to generate new and future propensities that may bring about the weakening and eventual demise of control forces. Political, military, and economic control, therefore, is a temporaryFootnote 37 and passing phase of an ever-emerging world where consciousness, practices, and transactions combine to constitute new propensities for change. Even in the worst cases of domination in history, control was contingent, partial, and transient. As Hitler and Mussolini extended their totalitarian control over most of Europe and aimed at doing the same over the rest of the world, they released the opposing forces that brought about their destruction. Thus, if we were to look at an apparent stable condition of domination with a magnifying glass, we would be able to see the pushbacks and learning processes that make domination only relative, vulnerable, and transient. Unlike Katzenstein and Seybert, therefore, we should not take control power and protean power as possessing equal ontological status. The social world is a world of physical and social propensities and thus a world of different degrees, grades, and intensities of protean power.

Agile agentsFootnote 38

As I mentioned in the Introduction, all agents are ‘agile’, even those who appear to be rigid or slow are creative.Footnote 39 According to Joas, human beings' most basic form of action – which all other forms of action, such as rational choice and intentionality, are related to – is creativity. Creativity is not just an occasional, exceptional occurrence. It involves all cases of social action and therefore agency. Creativity arises as the most basic form of action in situations calling for solutions to problems – when certainties are shattered and ‘when new forms of acting take on the form of changed routine’,Footnote 40 namely innovation. Creativity increases instability but, as Katzenstein and Seybert observe, it is a practice to reduce uncertainty. In my view, it also reduces entropy (disorder) by creating propensities for the establishment of new social orders.Footnote 41

Joas's view of creative social actionFootnote 42 rests on the argument that goals emerge from shifting situational contexts that improvising practitioners face and from reflection, aspirations, and dispositions.Footnote 43 As Joas says, ‘our perception is directed … towards our being able to use in practice in the context of our action that which we perceive’.Footnote 44 The argument that situations constitute action accords with Popper's propensity assumption.Footnote 45 Situations thus generate indeterminate propensities that creative action is based on.

Power and practices

Katzenstein and Seybert open only a small window for examining how practices and protean power interact. They examine how the interaction of the phenomenological and structural dimensions characterized by risk and uncertainty constitute political practices of innovation, improvisation, affirmation, and refusal. These practices then ‘feed back on uncertainty and risk depicted along the two dimensions’ and produce both control and protean power.Footnote 46 Katzenstein and Seybert thus distinguish between power and practices in a way that positivists would find familiar. Power and practices are, however, not so easily distinguishable; they are neither independent variables nor dependent variables. Rather, protean power operates through practices: for example, innovation and experimentation do not produce protean power, rather they, including their skillful performance, are protean power. They are propensities for affecting the construction of social reality in a certain direction. Practices, in turn, require material power and social power.Footnote 47 With performative powerFootnote 48 and deontic powerFootnote 49 agents, either as individual practitioners or as part of communities of practice,Footnote 50 can overcome competing practitioners and communities of practice in their struggle for constructing social reality.

It follows, therefore, that protean power rests not only on innovation, improvisation, and other such political and agile practices, but also on the selection of practices among various propensities. By selection of practices, I do not mean a choice, let alone a rational choice that people make, but processes through which practices spread and become institutionalized. At the same time, these processes rest on additional political practices, such as building institutions, using new media technologies, creating political coalitions within and across states, and discursively mobilizing public opinion.

The selection of practices involves both learning and contestation; the two processes are not mutually exclusive. Even though some practitioners may have more material and organizational resources (as well as deontic and performative power) at their disposal than others to promote the selection of their practices, selection processes are fundamentally indeterminate and exhibit both contextual and experiential uncertainty. To be sure, political practitioners usually believe that they live in a world which they can causally affect and they thus habitually (if not always) take risks.

Politics as actualization of propensities

I agree with Hannah Arendt, as referred to by Katzenstein and Seybert, that power emerges as the actualization of a reality when people act in concert.Footnote 51 But I have two qualifications. First, as I have shown above, power does not rest on potential inherent in physical objects, but on propensities inherent in the relational nature of unfolding situations. Second, based on this notion of power, we should think of politics as processes by which agents actualize or ‘freeze’ propensities through political action and practices, and of our knowledge of politics as explaining these processes. Aristotle thought of power to be inherent in things, and thus to be a potential capacity that waits to be realized.Footnote 52 I argue, however, that power does not exist until propensities are realized; it does not ‘wait’ around, because it is inherent in emergent processes and relations. Power, thus, lies not only in agents' potential to dominate each other, but also in acting in concert to turn propensities into reality.Footnote 53 Politics, therefore, amount to a constellation of practices, such as binding, promising, combining, covenanting,Footnote 54 contesting, and learning, through which agents collectively govern societies; manage and resolve conflict; organize, and guide interconnectedness and dissociation processes; and strive to keep social orders meta-stable or to bring about their evolution.Footnote 55

Epistemological uncertainty and protean power

As Katzenstein and Seybert argue, uncertainty is due to epistemological reasons, namely our partial knowledge of the world. Among other reasons, unforeseen events take place because of the indeterminate conditions generated by human interpretation; the changing and dynamic nature of intersubjectivityFootnote 56; creative ideas that acquire epistemic authority through political processes; and the construction of social reality by deontic power.

Another important source of partial knowledge of reality, however, is the complex interaction between political practitioners' and political observers' partial knowledge. Harlan Wilson caught this complex interaction by referring to two kinds of complexities.Footnote 57 ‘Situational complexity’ is the understanding of interdependent facts by the actors themselves. By contrast, ‘analytical complexity’ refers to the collective perception of a set of interrelated elements, as perceived by the observer of action.Footnote 58 When situational complexity and analytical complexity combine to create a circular type of understanding between political agents and political analysts, radical uncertainty and indeterminism results. In the face of this kind of social complexity – let us call it ‘compound social complexity’ – combined with a world that by nature is indeterminate, only protean power is possible. This is another reason why we are so often surprised by events: the fact that we do not perceive the indeterminate effects of protean power practices does not mean that they are not there.

For the above-mentioned reasons, and also because of ontological indeterminacy, an evolutionary epistemology and methodologies that trace practices and the flow of events are more realistic than epistemologies and methodologies attempting to explain and predict outcomes as produced by ‘independent variables’.

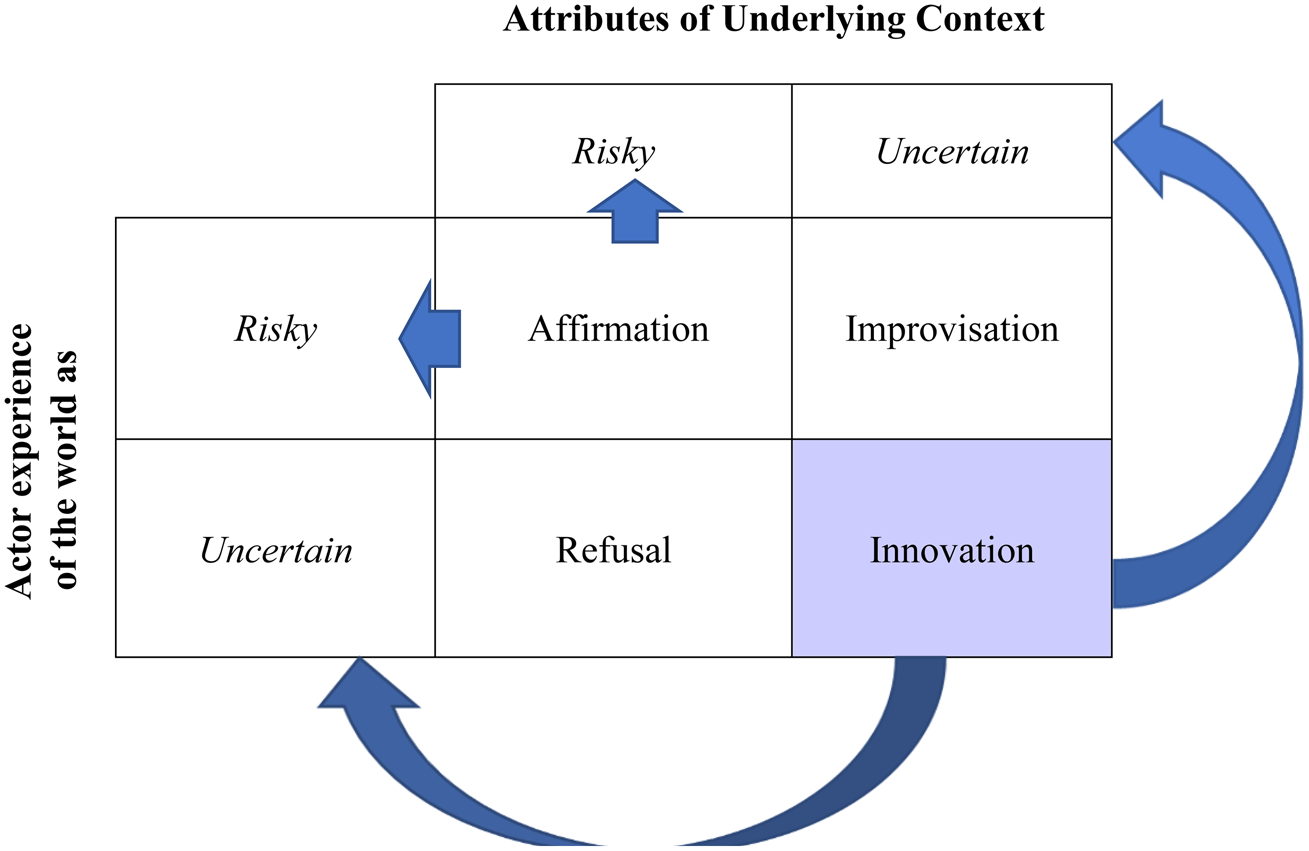

Finally, I return to Katzenstein and Seybert's Figure 1.1 (recapitulated as Figure 1).Footnote 59 The figure juxtaposes the same two attributes – risk and uncertainty – of the context and of the agents' experience. The juxtaposition yields four kinds of practices: (1) affirmation (control power can be applied), which results from combining the two risky scenarios; (2) innovation, which results from combining the two uncertain scenarios; (3) improvisation, which results from the combination of an uncertain context and risky experience; and (4) refusal to control, which results from the combination of uncertain experience and risky context.

Figure 1. Context, experience, and power according to Seybert and Katzenstein (Figure 1.1 from ch. 1, p. 13).

Following this paper's arguments, I suggest revising Figure 1 as follows: on the context side, I suggest two attributes: meta-stability (small fluctuations) and volatility (large fluctuations). On the actors' experience side, I suggest two attributes: illusion of control and no illusion of control. This figure yields six kinds of practices: (1 and 2) intervention and social engineering, as the combination of meta-stability and illusion of control; (3 and 4) experimentation and improvisation, which result from the combination of meta-stability and no illusion of control; (5) innovation, which results from the combination of volatility and illusion of control; and (6) collective (both structural and subjective) learning, which results from the combination of volatility and no illusion of control (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Adler's revised version of Figure 1.

To illustrate the six resulting practices in just a few sentences, take the threats to humanity posed by the combination of advances in AI and Bio-Engineering.Footnote 60 The combination of meta-stability and illusion of control yields a pattern of actions consistent with corporate regulations, state management, and technical fixes. The combination of meta-stability and no illusion of control yields experimentation and improvisation of state policies aimed at regulating corporations and overcoming adversaries, whereas engaging the latter with international ‘AI-control agreements’. The combination of volatility with illusion of control mobilizes scientists who create communities of practice, such as the Asilomar conferences, where hundreds of scientists, technologists, and ethicists aim to find ways to curb, both technologically and socially, AI's negative effects. AI possible negative effects are, for example, unmanned war, the ‘hacking of minds’ as in the 2016 US presidential election, and the loss of hundreds of millions of jobs around the world. Finally, the combination of volatility and no illusion of control should yield (though I doubt that it will any time soon) collective learning involving structural change and cognitive evolution.Footnote 61 Preventing learning algorithms from replacing humanity will require global cooperation, which in turn will involve major identity changes and the creation of an AI global governance system of rule.

Conclusion

My paper takes Katzenstein's and Seybert's main thesis on protean power to its irresistible yet radical conclusion. Political, military, and economic control is a temporary and passing phase of a constantly emerging reality. Human experience of control is, therefore, an illusion; all forms of power are a special, transient, and unstable case of protean power. One of the most important reasons, albeit not the only one, of why taking risks is governed by critical uncertainty is that the latter derives not only from our lack of perfect knowledge but also from the indeterminate condition of the natural and social worlds. In a constantly emerging world, creativity, the unintended consequences of our control attempts, and the self-defeating consequences of agency because of the responses it may provoke create not only new alternatives for action, but primarily propensities for the evolution of reality.

World politics' protean power should therefore caution us about how to approach the current world order's unsettling condition. To loosely paraphrase Karl Marx, humans create world order not as they please (or find it less risky), but as the propensities they set in motion end up becoming what they are. Although our current transitional and radically uncertain world order will end up becoming somewhat different from our attempts to control it, protean power may not be bad news after all, particularly for those who cherish, as I do, a liberal democratic world order. The reason of this is that if people can find the courage and determination to inject common humanity values to the dynamic processes that govern world order, they may end up affecting reality itself. Defeating populist authoritarianism, and preventing environmental catastrophe and human vulnerability due to AI and nuclear weapons may depend less on brute power and risk taking under the illusion of controlling events, technology, and human passions. Rather it may depend largely on creative human agency directed at mobilizing peoples to embrace and practice common humanity values.

Dedication

I dedicate this paper to the memory of Lucia Seybert and express gratitude to Jacques Hymans for organizing this Forum and to Peter Katzenstein for inviting me to participate in this inspiring intellectual endeavor.