Introduction

Because of their generally poor preservation, relatively little is known about early textiles and cordage, or the materials from which they were made. The identification of fibres recovered from the Neolithic settlement of Çatalhöyük in southern Anatolia, for example, has long been a matter of contention, with the same material identified by different specialists as either flax or as wool. The possibility of other fibres, however, has been neglected. Recently, awareness of the use of tree bast fibres for making string, netting and textiles has increased; such fibres are now well documented from a number of prehistoric contexts in Europe (Rast-Eicher Reference Rast-Eicher, Bichler, Grömer, Hofmann-de Keijzer, Kern and Reschreiter2005, Reference Rast-Eicher and Sofaer2018). Cordage and string were usually made of tree bast, mostly of willow, oak or lime, but lime bast was also used for woven textiles (Rast-Eicher & Dietrich Reference Rast-Eicher and Dietrich2015). Depending on the location of the bast layers within the bark, tree bast fibres farthest from the bark can be very fine and their morphology can resemble that of flax fibres, with, for example, similar diameters. This new knowledge has made it important to (re)investigate the textiles and fibres recovered from Çatalhöyük. Recent discussions about these fibres and others from early sites in the Near East, such as Wadi Murabba’at and Nahal Hemar in Israel, have focused on flax, and specifically on whether it was domesticated or traded (Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Bogaard, Charles and Filipović2014; Bar-Yosef Reference Bar-Yosef, Schier and Pollock2020; Shamir & Rast-Eicher Reference Shamir, Rast-Eicher, Schier and Pollock2020). The use of tree basts, which involves a chaîne opératoire that is somewhat different from that of flax, has not previously been considered as tree bast is not reliant on cultivation or animal husbandry.

Çatalhöyük

The archaeological site of Çatalhöyük consists of two mounds: Çatalhöyük East, which is Neolithic, and Çatalhöyük West, which dates largely to the Chalcolithic period. During the Neolithic a tributary of the Çarşamba River ran between the two mounds and created a system of channels and islands with different landscape types (Ayala & Wainwright Reference Ayala and Wainwright2020). The site as a whole is very large (about 13ha); there are nearly 21m of deposits representing some 1150 years of continuous occupation by a complex society with a rich material culture (including wall paintings, figurines, graves with skeletal remains, stratified occupation in houses, and early ceramics).

The first excavations were undertaken between 1961 and 1965 (Mellaart Reference Mellaart1967). In 1993 excavations were resumed, first at the eastern mound by the Çatalhöyük Research Project, directed by Ian Hodder, and later at the western mound (Hodder Reference Filipović2014; Hodder & Kutlu Reference Hodder, Kutlu and Hodder2021; www.catalhoyuk.com). During both excavation campaigns, numerous objects fashioned from perishable materials were discovered, including cordage, basketry, matting and textiles. These textiles and cords were used in burials to wrap the deceased in a flexed position; baskets were also used in burials, particularly to contain babies, but also in other contexts; mats were used as floor coverings (Helbæk Reference Helbæk1963).

The age of the Çatalhöyük textiles

The textiles found during the Mellaart excavations derive from Level E VI A/B, originally dated to between 6200 and 5800 BC (Mellaart Reference Mellaart1964: 116). With advances in radiocarbon-dating methods, Bayesian modelling now dates the start of the Çatalhöyük East site to c. 7100 cal BC (Bayliss et al. Reference Bayliss, Brock, Farid, Hodder, Southron and Taylor2015; Hodder & Kutlu Reference Hodder, Kutlu and Hodder2021). Four habitation phases can now be defined: early (7100–6700 cal BC), middle (6700–6500 cal BC), late (6500–6300 cal BC) and a final phase (6300–5950 cal BC). This represents both a correction and a refinement of previously published dates (Cessford et al. Reference Cessford and Hodder2005; Hodder Reference Hodder and Hodder2014). The textile finds from the Mellaart and Hodder excavations all derive from the middle phase (Hodder & Kutlu Reference Hodder, Kutlu and Hodder2021: tab. 1.2) between 6700 and 6500 cal BC, a narrower time span than previously suggested (6700–6300 cal BC; Bayliss & Tung Reference Bayliss and Tung2017; Rast-Eicher & Bender Jørgensen Reference Rast-Eicher and Jørgensen2018).

Textile fibres at Çatalhöyük

The first textiles at Çatalhöyük were discovered in 1962 and excavated by palaeoethnobotanist Hans Helbæk (Helbæk Reference Helbæk1963). Helbæk emphasised that he was not a textile expert and refrained from describing the textiles in detail except for the fibres. He stated that all the textiles, apart from one piece of a string, were made from animal fibres, probably wool (Helbæk Reference Helbæk1963: 43–44). In 1963, the textile historian Harold Burnham examined the textiles and accepted Helbæk’s fibre identifications (Burnham Reference Burnham1965), but wool specialist Michael Ryder did not and concluded that some of the textiles were made of flax (Ryder Reference Ryder1965). Textile specialist Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood later confirmed Ryder's identification of plant-based fibres, probably flax (Vogelsang-Eastwood Reference Vogelsang-Eastwood1988). In 2013 textile remains were discovered in Building 52 and determined to have been made from domesticated flax (Hodder Reference Hodder2013; Fuller et al. Reference Fuller, Bogaard, Charles and Filipović2014).

Mellaart remained convinced that the textile fibres from Çatalhöyük were wool (Mellaart Reference Mellaart1967: 219). The arguments in favour of his position included the presence of nitrogen in the fibres, the absence of flax seeds at the site and the finds of sheep bones and rams’ skulls (Burnham Reference Burnham1965: 170, quoting Mellaart Reference Mellaart1962: 56, Reference Mellaart1964: 57, 66, 73). Recent excavations (Bogaard et al. Reference Bogaard, Charles, Livarda, Ergum, Filipovíc, Jones and Hodder2013: 98 & 128, Reference Bogaard, Filipovíc, Fairbairn, Grenn, Stroud, Fuller and Charles2017: 3, tab. 3; Filipović Reference Filipović2014: 57 & 59) have recovered only a very small quantity of flax seeds, confirming their scarcity. According to Bogaard et al. (Reference Bogaard, Charles, Livarda, Ergum, Filipovíc, Jones and Hodder2013), linseeds are absent from the mid- to later Neolithic layers, but are present in small quantities in the earlier Neolithic sequence. Filipović (Reference Filipović2014: tab. 4.5) lists 13 seeds of Linum species in total.

The basketry and matting recovered during the Hodder excavations have been examined by Willeke Wendrich and Philippa Ryan (Wendrich Reference Wendrich and Hodder2005; Wendrich & Ryan Reference Wendrich and Ryan2012), and Antoinette Rast-Eicher and Lise Bender Jørgensen have analysed the textiles and cordage (Bender Jørgensen & Rast-Eicher Reference Bender Jørgensen and Rast-Eicher2017; Rast-Eicher & Bender Jørgensen Reference Rast-Eicher and Jørgensen2018; Bender Jørgensen et al. Reference Bender Jørgensen, Rast-Eicher, Wendrich and Hodder2021).

Textile production in the Neolithic

Plant fibres were used for a multitude of purposes in the Neolithic period, including the production of thin, flexible fabrics using techniques such as twining and weaving. Threads for such fabrics were made by splicing (Leuzinger & Rast-Eicher Reference Leuzinger and Rast-Eicher2011; Gleba & Harris Reference Gleba and Harris2018), rather than by retting and spinning as in later periods. Instead, strips of fibres were joined end to end, with the ends overlapping; these strips were then rolled together by hand to produce a yarn, and two such yarns were plied together. Fine threads from the Neolithic period in Europe and the Near East are always plied. The technique probably derives from early string-production methods using tree bast. Twining is a very important technique in the Neolithic period, and is used to produce flexible fabrics (Schick Reference Schick1988; Alfaro Reference Alfaro2012); weaving marks a further development of this earlier technique (Bender Jørgensen et al. Reference Bender Jørgensen, Rast-Eicher, Wendrich and Hodder2021). All woven textiles from the Neolithic are made in simple tabby or plain weave.

Fibre analysis: materials and methods

Seventeen textiles (woven and twined) and 14 threads/strings made of plant fibres were recorded from the Neolithic layers in the East Mound of Çatalhöyük (Bender Jørgensen et al. Reference Bender Jørgensen, Rast-Eicher, Wendrich and Hodder2021). A small number of samples was selected for fibre analysis on site (export restrictions limited the number; Table 1). One sample was taken from a coiled basket (no. 20465) to analyse the stitching; the coils are mineralised and material identification was based on their siliceous remains (Table 1, sample 2; Wendrich & Ryan Reference Wendrich and Ryan2012). Four samples were taken from cordage or textiles (Table 1, samples 4, 9, 15 and 11). In addition, a sample was taken from a textile fragment from the Mellaart excavations, now stored at the Textile Research Centre in Leiden (Table 1, last line); the box containing this fragment was labelled ‘Textile from skull, lower layer VI’. As this sample is dated ‘summer 1963’ it may derive from the textile found in Room E VI,1 (Mellaart Reference Mellaart1964: 93; pl. XXIVa–b, Reference Mellaart1967: pl. 94). The samples were mostly charred; when a house burnt down, the plant material in the graves beneath the floors was ‘baked’, preserving the textiles.

Table 1. Catalhöyük textile samples dated to the Neolithic period (6700–6500 cal BC).

In the laboratory, the samples were mounted on aluminium stubs, which were then sputtered with gold (about 20νm). They were analysed with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Zeiss EVO 50, 15KV; SEM of the University of Bern, Switzerland, Institute of Geography, Oeschger Centre, analyses by A. Rast-Eicher). The results were compared with previous findings of plant bast fibres (Rast-Eicher & Dietrich Reference Rast-Eicher and Dietrich2015; Rast-Eicher Reference Rast-Eicher2016a & Reference Rast-Eicher, Harb and Bleicherb).

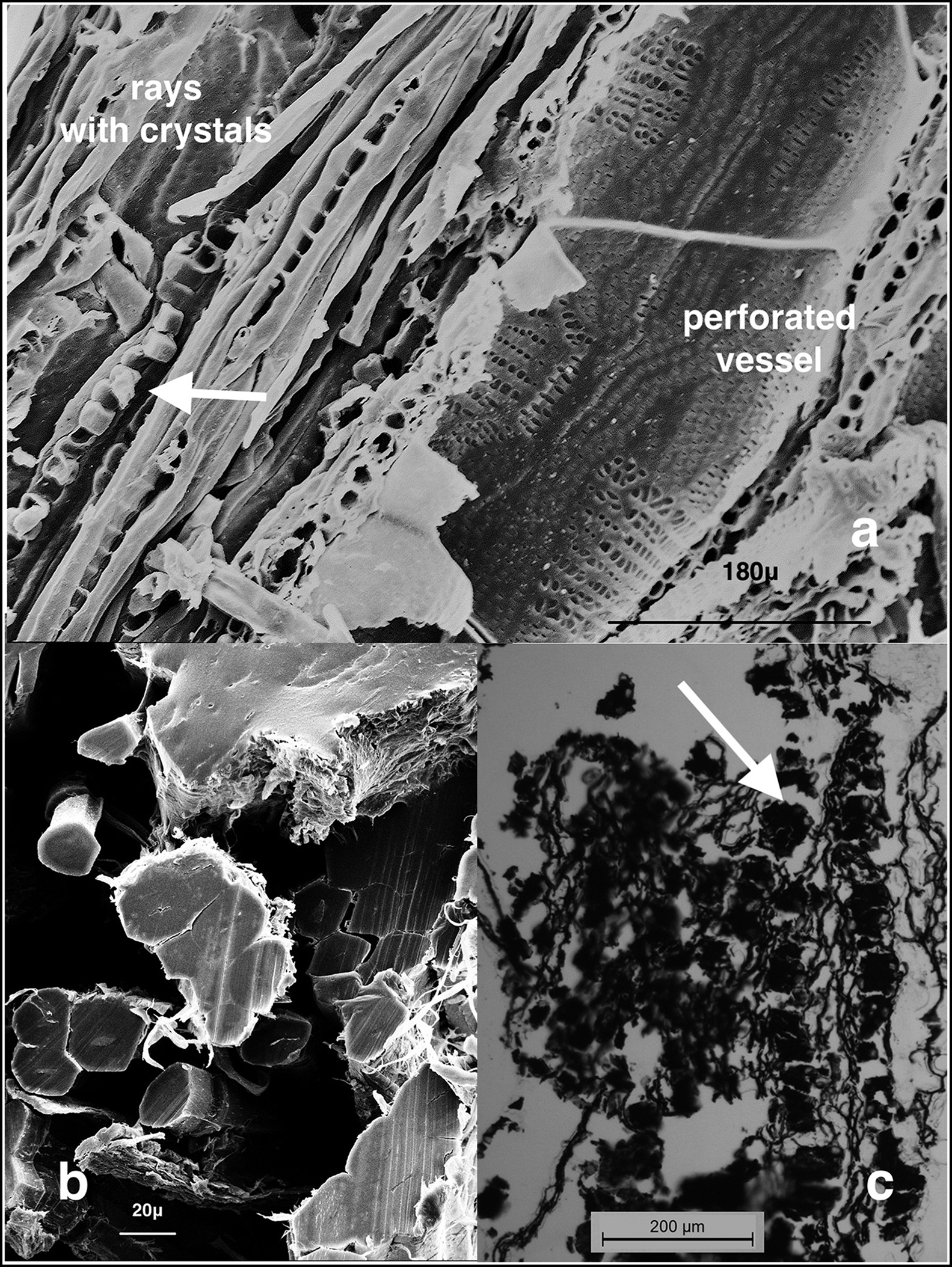

The identification of archaeological plant fibres is challenging. The main diagnostic feature shared by bast fibres (both flax and tree) is the presence of nodes, but there are important differences between the families. A range of characteristics must be checked: fibre diameter, the presence or absence of epidermis or rays with a clear morphology, the presence and form of crystals and stomata cells, the form of the fibres in cross-section, the form and diameter of the lumen (inner canal of fibre) and the twist of the cuticula. Flax has no rays and no large, perforated vessels. To enhance comparisons, modern reference material (both fresh and experimentally charred) was also prepared. Cross-sections were made with a microtome (HM 355S Thermo Fisher Scientific) and photographed with a Leica DM 5000B photo-microscope (Botanical Institute of the University Potsdam, Germany; preparations and photographs by Barbara Schmitz and Sabine Karg).

Results

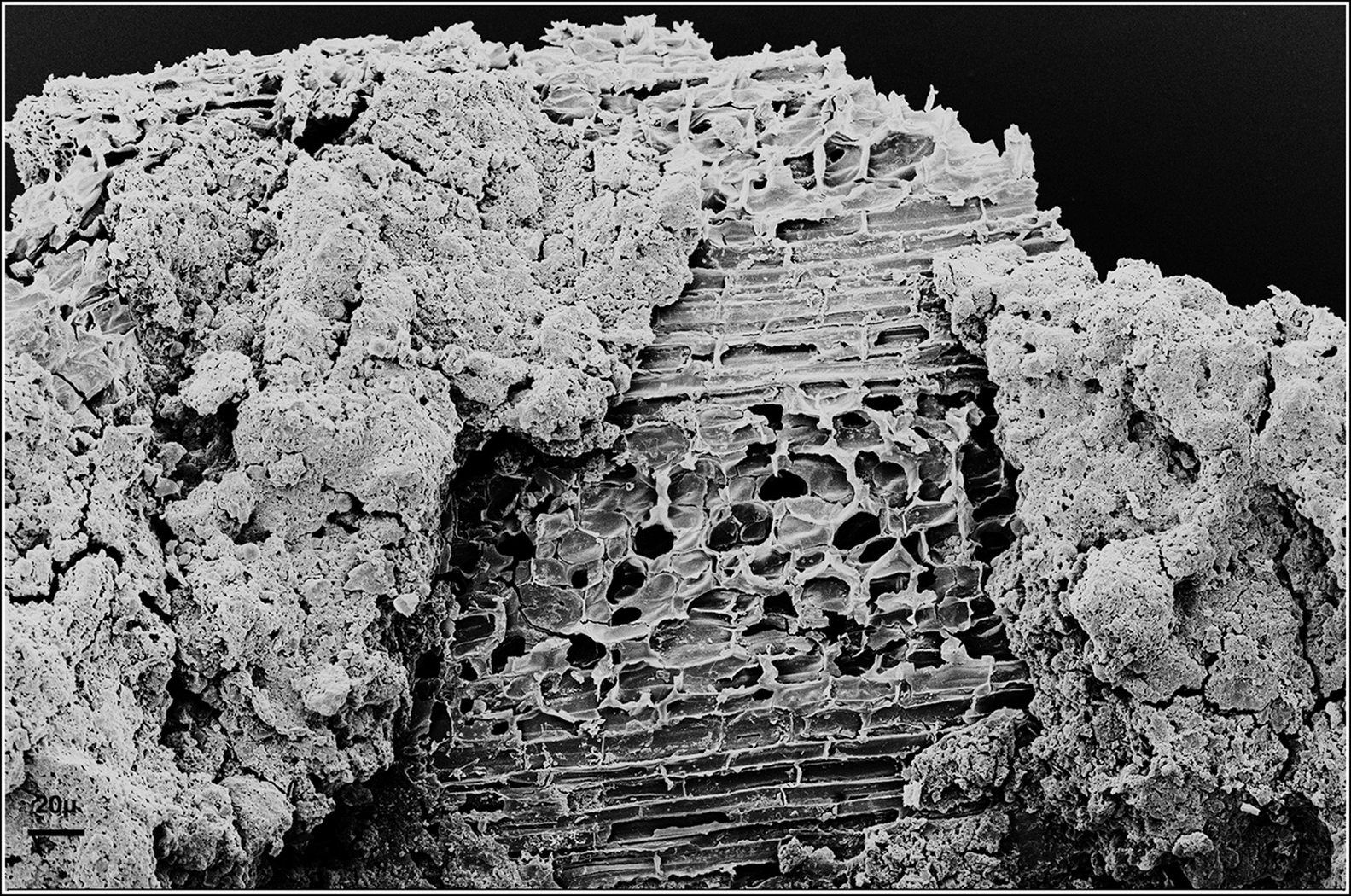

The sample taken from the stitching of a basket (sample 2) is made of grass blades (Gramineae sp.; Figure 1). The cordage (sample 4) from Building 52 (30511-s4), found wrapped around the legs of infant 30511-s6 (the same infant that yielded textile sample 11, see below), is oak tree bast (Quercus sp.) (Figure 2a). A large vessel with partly perforated cell walls, characteristic of oak, is visible on the right of the image; fibres and single-row rays can be seen on the left (crystals missing; empty cells visible). The fibres seen in cross-section are hollow (5–7μm diameter) (Figure 2b).

Figure 1. Çatalhöyük 20465: grass fibres used in the stitching of coiled basketry. Photograph: A. Rast-Eicher.

Figure 2. Çatalhöyük 30511-s4. Cordage: a) remains of oak bast with fibres and a large perforated vessel; b) cross-section with thick cell walls. Photographs: A. Rast-Eicher.

Oak bast was also identified in sample 11 (30503 s6-9), taken from a tabby-woven textile recovered with an infant in the same building (Building 52) as sample 4 (Figure 3). Twined and woven textiles are flexible objects and need well-prepared fibres. Threads from the Çatalhöyük textiles were spliced, with the fibres used as strips. This is why the remains of epidermis, or, as in sample 11, the remains of a large vessel, are still visible (Figure 4a).

Figure 3. Çatalhöyük 30503: tabby-woven fragment. Photograph: A. Rast-Eicher.

Figure 4. Çatalhöyük 30503-s8 (s6-9). Woven textile: a) fibres of oak bast with the remains of a perforated vessel (white arrows); b) cross-section with thick fibre walls and large lumen. Photographs: A. Rast-Eicher.

The textile (30503 s6-9; sample 11) was found in the thorax region of infant 30511-s6 (which had also yielded sample 4, the cordage 30511-s4 wrapped around the legs). The perforated vessel seen on the right side of the image of sample 11 (Figure 4a) appears as a small, crunched-up fragment. Both this sample and sample 4 show a large lumen in the cross-section (Figure 4b). Sample 11 is the same textile that Fuller et al. (Reference Fuller, Bogaard, Charles and Filipović2014) identified as made from domesticated flax. In order to confirm our identification, the morphological characteristics were compared with those of modern material (Figure 5). The perforation of the vessels seen in the fibres from Çatalhöyük are consistent with oak bast (Figure 5a); the cross section of wild flax shows a small lumen (as also seen in domesticated flax; see the dot in the centre of Figure 5b); the oak bast has a large lumen (large black space on Figure 5c)—an important diagnostic indicator for distinguishing flax from oak bast.

Figure 5. Comparative material: a) oak bast; b) cross-section of Linum bienne, charred; c) cross-section of oak bast, charred, with large lumen of fibres (arrow). Photographs a–b: A. Rast-Eicher; photograph c: B. Schmitz & S. Karg.

The woven textile from Building 49 (sample 9, 17457 X10) was made of spliced fibre bundles, which were not easily visible and probably covered by conservation products. No further details could be discerned, so that ‘plant fibres’ remains the appropriate identification. Samples 15 and 16 were obtained from a net or tassels of a textile found in Building 131. The threads are three-ply and made with large fibre strips. The cross-section shows substantial differences in the fibre diameters, thick-walled fibres with a very large lumen, but not as large as those seen with the oak bast fibres (Figure 6). The large bast strip shows an unusually large lumen for flax. The Leiden sample shows thick cell walls and a sizeable lumen—not as large as those from the samples identified as oak bast (samples 4 and 11), but larger than is usual in flax (Figure 7). No other morphological details, such as epidermis or rays, are visible: the determination is therefore unclear.

Figure 6. Çatalhöyük 22661-s5 from Building 131: thick-walled plant fibres with relatively large lumen. Photograph: A. Rast-Eicher.

Figure 7. Çatalhöyük sample from Leiden (Mellaart excavation): plant fibre with very large lumen. Photograph: A. Rast-Eicher.

Discussion

Early textiles made of plant fibres are rarely preserved in archaeological layers. In the Southern Levant, strings made of grasses (monocotyledons) have been identified at Ohalo II, a hunter-gatherer camp dated to 19 300 BP (Nadel et al. Reference Nadel, Danin, Werker, Schick, Kislev and Stewart1994). From the Early Neolithic period onwards, preserved twined textiles are reported from sites dated to the ninth and/or eighth millennium cal BC, such as Tell Aswad and Tell Halula in Syria, Nahal Hemar in Israel and Çayönü in Turkey. These are all reported as certainly or possibly made of flax (Schick Reference Schick1988; Vogelsang-Eastwood Reference Vogelsang-Eastwood1993; Stordeur et al. Reference Stordeur, Helmer, Jamous, Khawam, Molist, Wilcox, al-Maqdissi, Braemer and Dentzer2010; Alfaro Reference Alfaro2012).

Imprints of woven textiles have been found at Jarmo in Iraq (7000–6000 cal BC) and El Kown 2 in Syria (7100–6000 cal BC); further imprints from Tell Kashkashok in Syria and Telul eth Thalathat and Tell es-Sawwan in Iraq are all dated to the second half or the end of the seventh millennium cal BC (Bender Jørgensen et al. Reference Bender Jørgensen, Rast-Eicher, Wendrich and Hodder2021 with further references). The textile remains from Çatalhöyük, which belong to its middle phase (6700–6500 cal BC), therefore represent the earliest preserved woven textiles; together with the imprints from Jarmo and El Kown 2, they currently constitute the earliest-known evidence of weaving (Bender Jørgensen et al. Reference Bender Jørgensen, Rast-Eicher, Wendrich and Hodder2021). The only other preserved woven textile from the seventh millennium BC is from Ulucak Höyük, and dates to 6500–6000 cal BC (Çilingiroğlu Reference Çilingiroğlu2009). As for the imprints, fibre identification is not possible, and none have been reported at Ulucak Höyük.

Tree bast is often overlooked as the earliest processed plant material; in the search for early fibres, flax has dominated the discussion. A find from Georgia is claimed to represent the earliest use of wild flax for fibre production (Kvavadze et al. Reference Kvavadze, Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen2009), but this has been refuted because the fibre diameters are far too large (Bergfjord et al. Reference Bergfjord, Karg, Rast-Eicher, Nosch, Mannering, Allaby, Murphy and Holst2010). Another find, also initially thought to be flax, was a fine, S-plied thread used as binding to fix a wooden comb found in Wadi Mubarra'at (Israel, Jordan Valley) and dated to 9500 cal BC (Schick Reference Schick1995). New analyses of the string clearly show that it was made from fibres of tree bast with the remains of rays visible (Shamir & Rast-Eicher Reference Shamir, Rast-Eicher, Schier and Pollock2020: 34–35). A woven textile from phase X at Ilıpınar (Turkey), dated to 6000 cal BC (Roodenberg & Roodenberg Reference Roodenberg and Roodenberg2008: 6, fig. 14b), can also be added to the list. The fibres display structures untypical of flax, such as the remains of a perforated vessel (perforations and side wall of the vessel), indicating that the textile was made of tree bast (Rast-Eicher Reference Rast-Eicher2019).

In Europe wood bast has been identified at several sites. For example, a spindle found in Arbon (Switzerland) wound with lime bast yarn is dated to c. 3400 BC (De Capitani et al. Reference De Capitani, Deschler-Erb, Leuzinger, Marti-Grädel and Schibler2002). The substantial corpus of Neolithic textiles from European ‘lake dwellings’ includes a large textile with knotted pile, woven from lime bast, found in Zürich (Zürich-Mythenschloss; Rast-Eicher & Dietrich Reference Rast-Eicher and Dietrich2015: cat. no. 1001, pls. 106–107) and dated to the Corded Ware period (2750 BC, dendrochronological date). The fibre strips are quite large and fine rays are still visible (Figure 8), although the dimensions of the fibres are similar to those of flax fibres.

Figure 8. Zürich-Mythenschloss (Switzerland) 1375. Thread of tabby-woven textile made of lime bast (Tilia sp.). Photograph: A. Rast-Eicher.

The early history of flax domestication is the subject of ongoing research. The progenitor of domesticated flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) is Linum bienne Mill. (Linum angustifolium Huds.; Diederichsen & Hammer Reference Diederichsen and Hammer1995). This plant occurs widely in the Near East and Mediterranean area (Zohary et al. Reference Zohary, Hopf and Weiss2012), where it prefers moist habitats, as in the vicinity of Çatalhöyük (Ayala & Wainwright Reference Ayala and Wainwright2020). Only very few flax seeds have been recovered from the Neolithic layers of the site. In view of their small size, they were identified as most probably deriving from wild flax (Fairbairn et al. Reference Fairbairn, Near, Martinoli and Hodder2005: 174; Filipović Reference Filipović2014: 35, and personal information from Filipović 18.09.2019). Systematic seed measurements of modern flax varieties and of wild flax point to a clear difference in size (Karg et al. Reference Karg, Diederichsen, Jeppson, Siennicka, Rahmstorf and Ulanowska2018). As there is no evidence of domesticated flax at Çatalhöyük, we can advance the hypothesis that wild flax was collected close to the settlement.

Making woven textiles was probably a small-scale activity, following the hunter-gatherer tradition of exploiting wild plants for their fibres. The raw material was locally available. Tree bast was harvested in spring when the sap was rising within the tree trunks, which facilitates the removal of the bark with the attached bast. This would also be the case with wild flax: the bast strips would have still contained water and are easy to splice when taken from green stems (Leuzinger & Rast-Eicher Reference Leuzinger and Rast-Eicher2011). Based on the analyses of the phytoliths from the baskets from Çatalhöyük, the grasses (e.g. reed) were also collected in spring (Wolfhagen et al. Reference Wolfhagen, Veropoulidou, Ayala, Filipović, Kabukcu, Lancelotti, Madella, Pawłowska, Satiago-Marrero and Wainwright2020: 101). Analyses of charcoal and worked wood from the site show that oak was the most common wood species used for timber and fuel. Asouti (Reference Asouti and Hodder2005: 240–43 & 248–54) argues that oak grew within 10km of Çatalhöyük and that timbers were floated down the Çarşamba River following woodcutting trips during the spring.

Conclusions

Our analysis shows that tree bast, in this case from oak, was used to produce the earliest cordage and woven textiles recovered at Çatalhöyük and, indeed, the earliest known in the Neolithic period of the Near East. The textiles excavated in 2013, originally identified and published as ‘flax’, are in fact made from oak bast fibres, and this may well apply to several of the others.

The discovery that several Çatalhöyük textiles, the string from Wadi Murabba’at and the Ilıpınar textile were all made of tree bast fibres demonstrates that this resource played an important role in the early history of textiles and raises new questions regarding the apparent identification of flax fibres at other early sites. The results show a similar development in the Near East as previously documented for Neolithic Europe, where the use of tree bast fibres was common, even for woven textiles. We may conclude that the inhabitants of Çatalhöyük had a profound knowledge of the fibre properties of bast from oak, and probably other tree species, as well as wild flax. The environmental conditions around the settlement were suitable for harvesting different raw materials close by and there was no need to import textile fibres. Collecting raw material for baskets and textiles would have been part of the inhabitants’ activities during the spring, perhaps combined with the procurement of timber. Beyond their significance for Çatalhöyük itself, our results show that the precise identification of the raw materials used to produce fibres for textiles and cordage can throw light on the interpretation of plant domestication and plant use in prehistoric contexts.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to Ian Hodder for inviting us to the site in 2017 and to members of the team who shared their knowledge. We also thank Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood of the Textile Research Centre in Leiden for allowing us to investigate the 1963 sample, Jacob Roodenberg of the Netherlands Institute for the Near East for sending us the sample of the Ilıpınar textile and Werner Schoch for discussing the oak bast fibres. We thank the two anonymous reviewers for useful comments and John Peter Wild (Manchester, UK) for polishing our English.

Funding statement

A grant from the Stiftelsen Agnes Geijer's Fond för Nordisk Textilforskning made it possible for ArcheoTex to undertake the SEM analyses and write the text. The cross-sections for light microscopy were prepared within the framework of the research project FLAX (289510075), financed by the German Research Council.