The best men are not consistent in good—why should the worst men be consistent in evil?

―Wilkie Collins, The Woman in White Footnote 1Over decades, research has shown that supervisors who mistreat their employees cause significant harm to organizations and organizational members (Bamberger & Bacharach, Reference Bamberger and Bacharach2006; Mitchell & Ambrose, Reference Mitchell and Ambrose2012; Tepper, Simon, & Park, Reference Tepper, Simon and Park2017). Because of this impact, managers who enact abusive behavior have generally been termed malevolent, destructive, and overall unethical leaders (e.g., Brown & Mitchell, Reference Brown and Mitchell2010; Oh & Farh, Reference Oh and Farh2017). However, there is reason to believe that this description of the inherently “bad boss” might be inaccurate and too unidimensional in its form. Specifically, recent empirical evidence points to a larger complexity behind abusive supervision and those who perpetrate it. For example, meta-analytic mean ratings of the construct (M = 1.8; SD = 0.46) show that the raters of abusive supervision only seldomly Footnote 2 witness and/or experience acts of abuse in the workplace (Mackey, Frieder, Brees, & Martinko, Reference Mackey, Frieder, Brees and Martinko2017). Furthermore, research has shown that seemingly good and moral leaders can also become abusive in many situations (Lin, Ma, & Johnson, Reference Lin, Ma and Johnson2016). As such, it appears that abusive supervisors might not be wholly “bad.” Instead, managers might portray both bad and good behaviors, thereby presenting an amalgam of supervisory actions with which employees are confronted on the job.

Delving deeper into the complexity behind abusive bosses, the purpose of this article is to explore how employees view and react to managers who present both positive and negative characteristics at work. In particular, we aim to understand how employees make sense of and respond to abusive supervisors whose work efforts also make a positive difference in the lives of others—a concept referred to as prosocial impact (Grant, Reference Grant2007).Footnote 3 Drawing on two theories from the organizational justice literature—deonance theory (Folger, Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001) and fairness theory (Folger & Cropanzano, Reference Folger, Cropanzano and Greenberg2001)—we propose two competing ways in which subordinates process the interplay between “good” and “bad,” thus eliciting different behavioral reactions to abusive supervision: one that could preserve employee performance and another that could further harm employee performance.

In accordance with deonance theory, we first suggest that prosocial impact has a weakening effect on employee reactions to abuse. Subordinates might perceive prosocial impact as an instrumental factor that can minimize the potential wrong of abusive actions (Folger, Ganegoda, Rice, Taylor, & Wo, Reference Folger, Ganegoda, Rice, Taylor and Wo2013; Folger & Glerum, Reference Folger, Glerum, Cropanzano and Ambrose2015), thereby leading to more lenient retributive reactions in employees and leaving many performance outcomes (e.g., task performance, organizational citizenship behavior [OCB]) intact. Alternatively, fairness theory posits that employees might actually experience heightened thoughts of injustice when abusive bosses also positively affect the lives of others. As subordinates go through counterfactual thinking to evaluate unjust events, fairness theory states that a supervisor’s prosocial impact would make it more evident to subordinates that they should (and otherwise would) not be treated in an abusive fashion (Folger & Cropanzano, Reference Folger, Cropanzano and Greenberg2001). As a result, stronger injustice reactions emerge, which prompt employees to withdraw important performance efforts and increase their engagement in deviant acts.

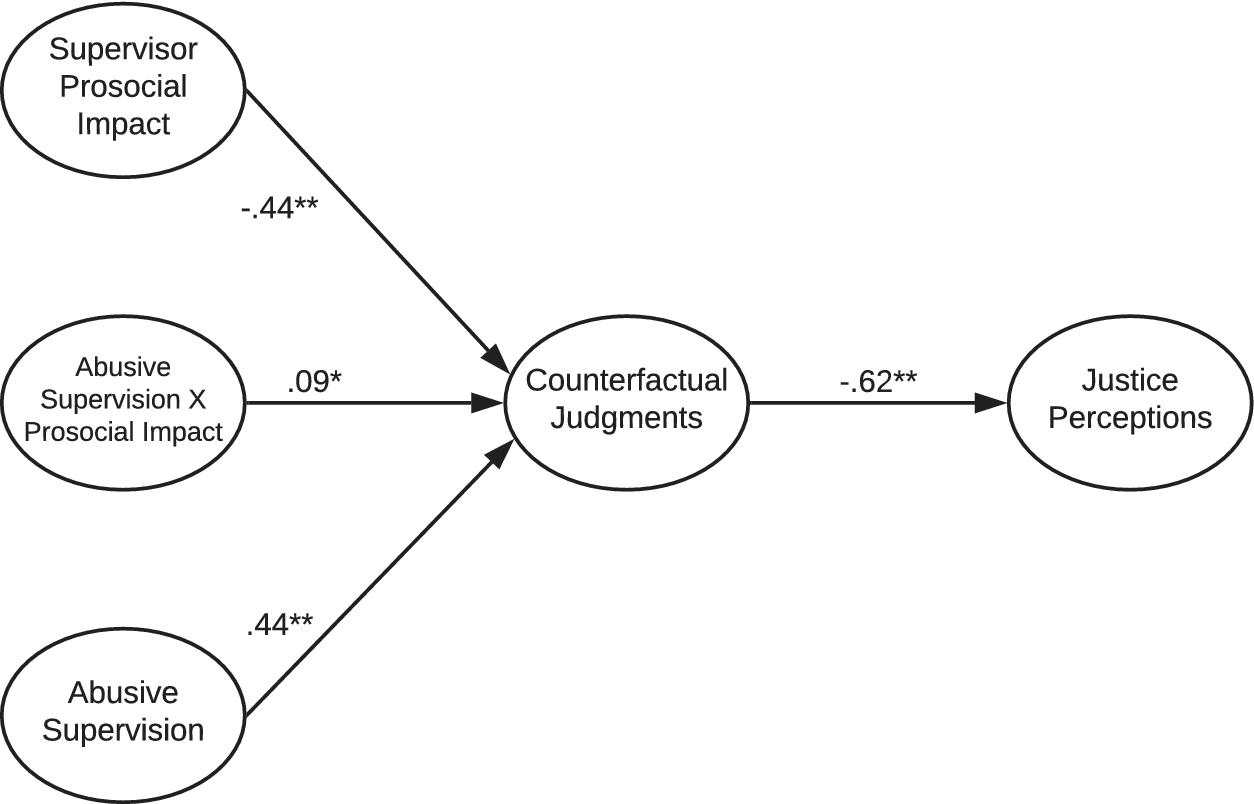

On the basis of these rationales, we propose a moderated-mediation model (Figure 1) that deciphers how employees process and react to abusive supervision when that very same manager also enacts positive change in the workplace. We test our model and these competing theories across three studies. The first two studies aim to determine which type of justice reasoning (the deontic or fairness approach) is dominantly used by employees when faced with an abusive supervisor who also has a prosocial impact. Furthermore, study 1 and study 2 are intended to shed light on the corresponding behavioral reactions subordinates display after making sense of the ethical conundrum. Upon finding consistent support for fairness theory (i.e., that prosocial impact strengthens negative reactions to the abusive supervisor), we conduct a third and final study to further investigate the specific cognitive process that fosters negative justice judgments and drives behavioral reactions on the part of abuse victims.

Figure 1: Study 1 and Study 2 Theoretical Model

In all, this article aims to contribute to research on abusive supervision and organizational justice in multiple ways. First, we hope to evolve the thinking around abusive supervision by challenging the previous portrayal of unidimensional perpetrators. In particular, we intend to show that abusers can simultaneously act in good and bad ways and that the positive behaviors they display will influence how employees ultimately process and respond to abusive supervision. Thus we join a growing literature stream that considers how employees make sense of and respond to abusive supervisors as a complex process (Li, McAllister, Ilies, & Gloor, Reference Li, McAllister, Ilies and Gloor2019).

In a similar vein, we consider a supervisor’s prosocial impact as an important boundary condition that might 1) make amends for abusive actions and thereby help maintain work behaviors or 2) lead to worse employee judgments, yielding many harmful performance responses. Finally, we contribute to theory within organizational justice and business ethics by building (and testing) a competing theoretical model using aspects of deonance (Folger, Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001) and fairness theory (Folger & Cropanzano, Reference Folger, Cropanzano and Greenberg2001). In doing so, we hope to gain insights into specific cognitive mechanisms that employees utilize to process fairness/ethical dilemmas involving their immediate managers and how those judgments influence work behaviors that are crucial for both the supervisor and the entire organization.

A DEONANCE AND FAIRNESS THEORY APPROACH TO ABUSIVE SUPERVISION

Abusive supervision has been described as a hostile leadership behavior that encompasses actions such as belittling and ridiculing employees as well as telling them that their thoughts and feelings are stupid (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000). As stated in the literature, these offenses deny just treatment to individuals in such a way that they are no longer treated with dignity and respect. Accordingly, research has considered abusive supervision to be unethical in nature (Brown & Mitchell, Reference Brown and Mitchell2010), and it has been theorized that employees use a moral lens to process supervisor abusive behavior (Oh & Farh, Reference Oh and Farh2017). As a result, tenets of both deonance (Folger, Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001) and fairnessFootnote 4 theory (Folger & Cropanzano, Reference Folger, Cropanzano and Greenberg2001) have been used to understand employee reactions to abusive supervision because these theories are evolutions in the justice literature that explore the ethical nature of justice. For example, in his seminal piece, Tepper (Reference Tepper2000) found that acts of abuse elicit many justice perceptions in employees, such that they feel unjustly treated on an interpersonal level by their supervisor as well as by their organization. Similarly, scholars draw on deontic principles to argue that witnesses of abuse think that imperative moral standards have been violated, which triggers adverse performance reactions in subordinates (e.g., Mitchell, Vogel, & Folger, Reference Mitchell, Vogel and Folger2015; Priesemuth & Schminke, Reference Priesemuth and Schminke2019).

Though these immediate reactions to abuse are valuable to understand, our interest in this article goes further, in that we seek to discern how employees view and react to supervisors who are abusive at work, yet simultaneously engage in many positive actions. To examine the interplay between “good” and “bad,” we delve deeper into the aforementioned theories.

Abusive Supervision, Deonance Theory, and Fairness Theory

At its core, deonance theory postulates that moral standards depict how individuals ought to behave and treat others (Folger, Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001). Unlike earlier justice research,Footnote 5 deonance theory argues that individuals view morality or justice as an end in and of itself, meaning that people care about justice because it is the right/moral thing to do and not because of self-interested reasons. As such, the theory emphasizes that employees believe supervisors (especially) should abide by and uphold ethical norms in all interactions (Folger, Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001). Naturally, when managers violate principles of ethical conduct (as is the case with abusive supervision), employees judge their leaders and actions to be unjust in nature (Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Vogel and Folger2015; Priesemuth & Schminke, Reference Priesemuth and Schminke2019).

Similar to deonance theory, fairness theory considers behaviors to be unjust when principles of proper treatment have been infringed (Folger & Cropanzano, Reference Folger, Cropanzano and Greenberg2001). Specifically, to make sense of justice violations, individuals are said to employ counterfactual thinking, which is fairness theory’s central underlying premise. In this counterfactual process, individuals who are faced with injustice imagine alternative scenarios of what appropriate treatment should, would, and could look like in other instances. For example, if a person is discriminated against in the hiring process, the person will view the discrimination as unfair if he or she can envision alternative realities where such discrimination couldn’t, wouldn’t, or shouldn’t occur. These different narratives then create a new frame of reference that helps people determine whether a current situation is just or unjust. That is, when employees are able to picture scenarios in which they would be better off (e.g., subordinates realize that abusive treatment should not be occurring and that this very same behavior would and could not be tolerated in other settings), they view their current abusive situation as unjust. A last component of these theories is that they are agnostic to content. That is, people are not focused on specific aspects of justice (e.g., distributive or procedural justice) but instead are interested in the way people think about and respond to (in)justice as a whole.

After deeming abusive supervision to be an act of injustice, both fairness (Folger, Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001) and deonance theory (Folger & Cropanzano, Reference Folger, Cropanzano and Greenberg2001) suggest that individuals subsequently have a strong desire to restore justice and punish the transgressor. Hence employees have been shown to display retributive actions that will harm the abusive supervisor, even if it comes at a personal cost to the employee (Folger, Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001; Turillo, Folger, Lavelle, Umphress, & Gee, Reference Turillo, Folger, Lavelle, Umphress and Gee2002).

The justice literature points to two specific types of workplace retaliation: one that is overt and direct and another that is covert and more subtle (Skarlicki & Folger, Reference Skarlicki and Folger1997). Overt retaliatory acts are those where individuals aim to directly harm and punish the wrongdoer because of the justice violation (Greenberg, Reference Greenberg1990, Reference Greenberg1993). Thus employees engage in aggressive and sabotaging behaviors that are explicitly directed at the abusive boss (Mitchell & Ambrose, Reference Mitchell and Ambrose2007; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Vogel and Folger2015). To capture this type of overt retribution, we look to supervisor-directed deviance, which includes behaviors like acting rudely toward the supervisor or saying hurtful things to him or her (Mitchell & Ambrose, Reference Mitchell and Ambrose2007; Rotundo & Sackett, Reference Rotundo and Sackett2002).

Employees also retaliate against the perpetrator by engaging in covert counterproductive work behaviors. This type of aggression is especially relevant when abused individuals are less powerful than the source of injustice (i.e., the supervisor; Skarlicki & Folger, Reference Skarlicki and Folger1997). In these covert undertakings, subordinates are prone to punish an abusive boss by purposefully withholding important work efforts that could benefit the transgressor. Two behaviors that have been shown to significantly aid managers’ daily work life, as well as their overall success in the organization, are supervisor-directed OCB and task performance (Hogan & Hogan, Reference Hogan and Hogan2001). OCB is a voluntary performance behavior in which employees, for instance, dedicate extra time to assist the supervisor with his or her workload (MacKenzie, Podsakoff, & Fetter, Reference McClelland and Judd1993). Similarly, task performance entails actions that contribute to the overall work environment and its goals (Organ, Reference Organ1988; Rotundo & Sackett, Reference Rotundo and Sackett2002; Williams & Anderson, Reference Williams and Anderson1991), both of which are central elements and measures of supervisor effectiveness (Hogan & Hogan, Reference Hogan and Hogan2001). Hence a withdrawal in employee citizenship and task performance could harm an abusive superior and this person’s standing in the organization. Supporting this logic, research confirms a negative relationship between abusive supervision and these performance behaviors (e.g., Harris, Kacmar, & Zivnuska, Reference Harris, Kacmar and Zivnuska2007; Zellars, Tepper, & Duffy, Reference Zellars, Tepper and Duffy2002).

In sum, we draw on deonance and fairness theory to suggest that abusive supervision invokes judgments of injustice in employees, which in turn spark retaliatory motives in subordinates. To consider this retaliation, we take a holistic view of the employee’s performance by considering that employees are inclined to punish the abusive supervisor by turning to 1) employee deviance, 2) reduced citizenship behaviors, and 3) reduced task performance. Accordingly, we argue that justice perceptions mediate the relationship between abusive supervision and 1) supervisor-directed deviance, 2) supervisor-directed OCB, and 3) task performance. Formally, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1a: Justice perceptions mediate the positive relationship between abusive supervision and supervisor-directed deviance.

Hypothesis 1b: Justice perceptions mediate the negative relationship between abusive supervision and supervisor-directed OCB.

Hypothesis 1c: Justice perceptions mediate the negative relationship between abusive supervision and employee task performance.

After describing how employees generally react to abusive acts, we now explain how employees might respond to abusive supervision when the perpetrating manager also has a prosocial impact at work. As we continue to draw on deonance and fairness theory, we craft opposing arguments where the deontic perspective depicts how the supervisor’s prosocial impact could help abused individuals and their destructive responses. In turn, we utilize the fairness perspective to postulate that prosocial impact could make the current situation significantly worse for employees. In the following pages, we first focus on the mitigating effect of prosocial impact before explaining how “doing good for others” may further harm victims in mistreatment situations.

The Beneficial Effect of Prosocial Impact: A Deonance Theory Perspective

As deonance research has largely examined moral transgressions in isolation (e.g., it explores how employees react to specific immoral conduct), scholars have recently broadened this assumption and suggested that individuals also consider alternative information before making final judgments about the wrongdoing. In particular, Folger and colleagues proposed that individuals focus on two factors, an inherent and an instrumental classification, when assessing the severity of unethical conduct (Folger et al., Reference Folger, Ganegoda, Rice, Taylor and Wo2013; Folger & Glerum, Reference Folger, Glerum, Cropanzano and Ambrose2015).

To elaborate, individuals first reflect upon an inherent factor, by which they assess whether the transgression itself violates universal moral principles (Folger, Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001). Though this inherent factor is consistent with the traditional conceptualizations of deonance theory, the instrumental factor goes further. This factor suggests that victims of unethical actions also consider the overall impact the transgressor might have on others and if the transgressor is creating positive consequences for others (Folger et al., Reference Folger, Ganegoda, Rice, Taylor and Wo2013). In other words, people also evaluate the instrumentality of the perpetrator and the influence he or she might have through work activities (e.g., Harris et al., Reference Harris, Kacmar and Zivnuska2007).

Beyond assessing unethical practices more holistically, deonance theory further states that positive instrumental factors (like prosocial impact) might be particularly powerful in shaping final justice judgments and reactions. Specifically, the theory holds that the instrumental factor redraws the equilibrium of what is perceived as justifiable and acceptable behavior from the individual. Because the manager creates a high level of good through the prosocial impact, the employee will view that he or she deserves some concessions and leeway on violations of inherent values (Folger & Glerum, Reference Folger, Glerum, Cropanzano and Ambrose2015). As such, the positive instrumental factor presents the transgressor and his or her actions in a much more positive light, which likely elicits more favorable reactions to the enacted misconduct (e.g., Folger et al., Reference Folger, Ganegoda, Rice, Taylor and Wo2013). In essence, a supervisor’s prosocial impact can make amends (to some extent) for his or her abusive behaviors, which then mitigates thoughts of unfairness. Thus we also expect fewer retaliatory behaviors, such that employees are less inclined to respond to abusive supervision by reducing performance output and increasing deviant acts.

Together, we follow the inherent and instrumental characteristics of deonance theory to propose that employees will be less likely to judge abusive supervision as a justice violation when the supervisor also has a prosocial impact with his or her work. Supervisor prosocial impact should thereby weaken the indirect effect between abusive supervision and employee reactions through justice perceptions. We predict a first-stage, moderated-mediation model as shown in Figure 1. Formally, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: A supervisor’s prosocial impact will moderate the indirect relationship between abusive supervision and employee outcomes such that the positive relationship between abusive supervision and 1) supervisor-directed deviance and the negative relationship between abusive supervision and 2) supervisor-directed OCB and 3) task performance through justice perceptions will be weaker at high levels of prosocial impact.

The Harmful Effect of Prosocial Impact: A Fairness Theory Perspective

Although deonance theory depicts a mitigating or beneficial effect of prosocial impact on supervisor abuse perceptions and responses, other work in the organizational justice literature suggests the opposite, indicating that individuals might perceive even stronger justice violations when the abusive boss also appears to be a good person. Recall that fairness theory posits that justice judgments and subsequent reactions depend on the victim’s counterfactual thinking, in which he or she creates alternative scenarios to determine whether the current situation is just or unjust (Folger & Cropanzano, Reference Folger, Cropanzano and Greenberg2001). When these alternative realities are worse than the current situation, the person is likely to view the current state as just. In contrast, when these narratives are better than the current reality, the person perceives the current situation as unjust.

Considering the nature of abusive acts, a subordinate likely imagines an improved alternative reality in which he or she is not mistreated by the supervisor, which, subsequently, triggers feelings of injustice (Folger, Reference Folger and Kessler2014). However, we believe that these perceptions of injustice are even further amplified when the abuser also has a prosocial impact on others. This is because the positive factor of prosocial impact further accentuates a potential reality in which the supervisor should not and would not be treating a subordinate this way (Duffy, Ganster, Shaw, Johnson, & Pagon, Reference Duffy, Ganster, Shaw, Johnson and Pagon2006). Furthermore, it becomes even more evident that the perpetrator could act differently if he or she chooses to. It is even plausible that the superior could make a positive difference in the life of this employee instead of harming this person. As such, the employee feels even more betrayed and unjustly treated, eliciting stronger injustice perceptions and greater retaliatory behaviors (Folger & Skarlicki, Reference Folger and Skarlicki1998).

In all, we draw on fairness theory to argue that a supervisor’s prosocial impact could strengthen the relationship between abusive supervision and subordinate reactions, which yields the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: A supervisor’s prosocial impact will moderate the indirect relationship between abusive supervision and employee outcomes such that the positive relationship between abusive supervision and 1) supervisor-directed deviance and the negative relationship between abusive supervision and 2) supervisor-directed OCB and 3) task performance through justice perceptions will be stronger at high levels of prosocial impact.

OVERVIEW OF STUDIES

We conducted three studies to test our predictions. Given the importance of replication to science (Köhler & Cortina, Reference Köhler and Cortina2019) as well as the competing format of our hypotheses, studies 1 and 2 are intended to explore whether a supervisor’s prosocial impact positively or negatively influences the indirect relationship between abusive supervision and employee retaliatory reactions through justice perceptions (hypotheses 1–3). After consistent and robust findings from these first two studies, we employ a third study to further extend our knowledge regarding key processes employees use to make sense of abusive and prosocial characteristics of supervisors. To do so, we build two final hypotheses, which we test in study 3. Taken together, these studies provide a strong test of key theoretical developments and their components to help better understand how employees view unjust managers.

STUDY 1

Method

Sample and Procedure

Following previous work in ethics and mistreatment (e.g., Greenbaum, Mawritz, Mayer, & Priesemuth, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz, Mayer and Priesemuth2013; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Vogel and Folger2015), we utilized a snowball technique to recruit employed individuals to participate in this study. To collect these data, we offered business students extra course credit in exchange for identifying a working adult who could serve as a contact and potential respondent. If the employee agreed to participate, the individual received a secure online survey link. This sampling strategy has been shown to produce comparable correlations, effect sizes, and population representativeness to other techniques (e.g., Wheeler, Shanine, Leon, & Whitman, Reference Wheeler, Shanine, Leon and Whitman2014).

Because traditional survey methods make it difficult to assess specific responses to mistreatment events (Hershcovis, Reference Hershcovis2011), we followed scholars’ recommendations to embed a critical incident technique (CIT) into our survey. CITs have been shown to be valid and effective ways to examine employees’ direct perceptions of and responses to abuse by a supervisor (e.g., Bobocel, Reference Bobocel2013; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Vogel and Folger2015; Priesemuth & Schminke, Reference Priesemuth and Schminke2019). As such, we asked employees to recall and write about a specific event during the past year in which they experienced abusive supervision, such as being yelled at or being put down by their supervisors. Participants were asked to write about the incident with as much detail as possible. After writing about the incident, participants rated their supervisors’ abusive supervision and described how they thought and behaved after the critical event. That is, they assessed the mediating mechanisms (i.e., justice perceptions) as well as the dependent variables (i.e., task performance, supervisor-directed OCB, and supervisor-directed deviance). Finally, employees reflected on the supervisors’ prosocial impact and rated those items as well.

Five hundred fifty-five individuals completed our survey (60 percent response rate). We first coded the qualitative responses and dropped those who could not write about an incident involving abusive supervision (N = 47). Because of the importance of attentive responses (Clark, Gironda, & Young, Reference Clark, Gironda and Young2003), we took several steps to ensure the validity of responses, including 1) emphasizing the integrity of the scientific process, 2) comparing email addresses for each participant, 3) filtering out those who completed the survey too rapidly, and 4) embedding instructed response items (e.g., Meade & Craig, Reference Meade and Craig2012). Those who did not meet these criteria were removed from the analyses, resulting in a usable sample of four hundred employees. Approximately half of our sample was employed in the finance, food service, and retail industries. Fifty percent of participants were male, and 59 percent were Caucasian. On average, they were twenty-two years old (SD = 4.6), had two years (SD = 2.3) of organization tenure, and worked twenty-five hours per week (SD = 10.9).

Measurement

Abusive supervision. Employees rated the level of abuse by the immediate supervisor about whom they wrote using Mitchell and Ambrose’s (Reference Mitchell and Ambrose2007) shortened five-item version of Tepper’s (Reference Tepper2000) scale. Participants were prompted to rate the supervisor about whom they wrote in the critical incident and to respond to items such as “My supervisor ridicules me” on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (I cannot remember him/her ever using this behavior with me) to 5 (He/she uses this behavior very often with me).

Prosocial impact. Employees indicated the degree to which they believed that actions of the supervisor (identified in the critical incident) had positive consequences on people’s lives. Respondents indicated their agreement with Grant’s (Reference Grant2008) three-item scale using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample item is “I feel that my supervisor’s work makes a positive difference in other people’s lives.”

Justice perceptions. In response to the described incident, employees rated their level of justice perceptions using three items from Ambrose and Schminke’s (Reference Ambrose and Schminke2009) overall justice scale. These items capture an individual’s personal justice experiences. Respondents indicated their agreement on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample item is “In general, the treatment that I receive around here is fair.”

Job performance. Employees rated their level of job performance after the abusive incident using Johnson and O’Leary-Kelly’s (Reference Johnson and O’Leary-Kelly2003) shortened version of Van Dyne and LePine’s (Reference Van Dyne and LePine1998) task performance scale. Because job performance is considered a socially desirable outcome that can be biased when self-reported, we employed a modified indirect questioning method to counter this potential shortcoming (Dalal & Hakel, Reference Dalal and Hakel2016). Hence we instructed employees to think about how their superiors would see and rate their job performance with items including “Meets the formal requirements of the job” on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree).

Supervisor-directed OCB. Employees also assessed the extent of their supervisor-directed OCB following the incident using the five-item scale by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman, and Fetter (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Moorman and Fetter1990). Employees indicated how often they engaged in behaviors such as “helping their supervisor when he/she has a heavy workload” using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (daily).

Supervisor-directed deviance. Employees indicated the extent of any supervisor-directed deviance after the abuse experiences utilizing Tepper, Carr, Breaux, Geider, Hu, and Hua’s (Reference Tepper, Carr, Breaux, Geider, Hu and Hua2009) shortened version of Skarlicki and Folger’s (Reference Skarlicki and Folger1997) scale. Respondents indicated their agreement with three items using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree). Sample items are “I disobeyed my supervisor’s instructions” and “I talked back to my boss.”

Control variables. We controlled for employee age because research has shown that younger individuals tend to respond more strongly to mistreatment (Specht, Egloff, & Schmukle, Reference Specht, Egloff and Schmukle2011). Additionally, we controlled for education, which has been a strong predictor of performance in the past (Ng & Feldman, Reference Ng and Feldman2009). Lastly, we included company tenure in our analyses, because a longer tenure offered employees greater chances of seeing abuse and prosocial impact simultaneously (Mitchell & Ambrose, Reference Mitchell and Ambrose2007). We note that our structural model remains consistent with or without these controls and therefore present all analyses, as recommended, without these variables (Becker, Reference Becker2005).

Results

The means, standard deviations, correlations, and internal consistency for all study variables appear in Table 1. Before proceeding with our analyses, we tested the acceptability of our measurement model with confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). As shown in Table 2, the six-factor measurement model demonstrates an acceptable fit to the data. Comparing this six-factor model to alternative models, the six-factor model yields a significantly better fit than other models. Demonstrating discriminant validity, Table 3 shows that each variable’s average variance extracted (AVE) estimate is larger than its squared correlation with any other variable (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981).

Table 1: Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations

Note: Study 1 correlations appear above the diagonal. Study 2 correlations appear below the diagonal. For study 3, alpha reliabilities appear in parentheses. Study 1, N = 400; study 2, N = 206; study 3, N = 159. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Table 2: Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Studies 1–3

Note. Models were tested using maximum-likelihood estimation in Mplus 8. DV = dependent variable. IV = independent variable.

Table 3: Average Variance Extracted, Composite Reliabilities, and Squared Latent Correlations among Variables

Note. AVE = average variance extracted. CR = composite reliability. OCB = organizational citizenship behavior. Squared latent correlations for study 1 appear below the diagonal; squared latent correlations for study 2 appear above the diagonal. All average variance extracted estimates are above the 0.5 acceptable level cutoff; all composite reliabilities were above the 0.7 acceptable level cutoff.

Because structural equation modeling (SEM) is one of the best ways of correcting for the biased estimates within moderation and mediation testing (Aguinis, Edwards, & Bradley, Reference Aguinis, Edwards and Bradley2016), we utilized SEM to test our mediation and moderated-mediation hypotheses. Prior to analyzing all hypotheses, we tested the fit of our structural model. Owing to the fit of maximum-likelihood estimation being robust to withholding latent interaction terms, we followed steps from Muthen and Muthen (Reference Muthen and Muthen2012) to first estimate the fit of a nonlatent interaction model. This structural model has an acceptable fit to the data (χ²[200, N = 400] = 362.73, CFI = 0.97, SRMR = 0.08, RMSEA = 0.05). Next, we estimated the latent interaction model utilizing latent moderated structural (LMS) maximum-likelihood estimation in Mplus 8 (Klein & Moosbrugger, Reference Klein and Moosbrugger2000). LMS maximum-likelihood does not return fit statistics; thus we compared this model to the nonlatent interaction model utilizing the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayes information criterion (BIC). The latent interaction model (AIC = 24,243, BIC = 24,805) shows a reduction in both AIC and BIC numbers (noninteraction model, AIC = 24,739, BIC = 24,808), indicating better fit. Figure 2 displays the results of the structural model.

Figure 2: Study 1 and Study 2 Structural Equation Model

Note. Study 1 results appear outside parentheses; study 2 results appear in parentheses. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Following evidence of acceptable fit, we proceeded to test our hypotheses. Because mediation testing, even within SEM, suffers from additional bias due to nonnormality (e.g., Hayes, Reference Hayes2013; Preacher & Hayes, Reference Preacher and Hayes2008), we utilized a bootstrap procedure in Mplus 8 using five hundred bootstrap samples to create bias-corrected confidence intervals.

Hypothesis 1 suggested that abusive supervision would be positively related to 1) supervisor-directed deviance and negatively related to 2) supervisor-directed OCB and 3) task performance through justice perceptions. As shown in Table 4, the indirect relationship between abusive supervision and 1) supervisor-directed deviance through justice is significant (ab = 0.02, CI95 [0.005, 0.057]) because the confidence interval did not include zero (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013). Similarly, the indirect relationships between abusive supervision and 2) supervisor-directed OCB (ab = −0.03, CI95 [−0.081, −0.012]) as well as 3) task performance (ab = −0.03, CI95 [−0.067, −0.010]) through justice are significant. In all, hypothesis 1 is fully supported.

Table 4: Mediation and Moderated-Mediation Results

Note. All significance levels correspond to a 95 percent confidence interval level. PSI = prosocial impact. Those marked with † are significant at a 90 percent confidence interval level. LLCI = lower-level confidence interval. ULCI = upper-level confidence interval.

*p < 0.05.

Hypotheses 2 and 3 concerned the competitive tests of the conditional indirect effect of prosocial impact. Hypothesis 2 took a deonance theory lens to state that prosocial impact would moderate the indirect relationship between abusive supervision and 1) supervisor-directed deviance, 2) supervisor-directed OCB, and 3) task performance through justice perceptions such that the relationship is weaker at high levels of prosocial impact. Conversely, hypothesis 3 followed the fairness theory perspective to suggest that these relationships would be stronger at high levels of prosocial impact. To assess the conditional indirect effects, statisticians have pointed to the index of moderated mediation as a reliable indicator because this index (when significant) shows that the indirect effect is significantly different at all levels of the moderator (Hayes, Reference Hayes2015). As shown in Table 4, the conditional indirect effects between abusive supervision and 1) supervisor-directed deviance (index of moderated mediation = 0.01, CI95 [0.001, 0.029]), 2) supervisor-directed OCB (index of moderated mediation = −0.02, CI95 [−0.042, −0.002]), and 3) task performance through justice are all significant (index of moderated mediation = −0.01, CI95 [−0.034, −0.002]). Consistent with these findings, Figure 2 also reveals a significant interaction between abusive supervision and prosocial impact on justice perceptions (B = −0.15, p ≤ 0.05). These results support moderation and moderated mediation in our sample.

In support of fairness theory and hypothesis 3, Figure 3 shows the direction of the moderation in that the relationship between abusive supervision and justice perceptions is stronger at higher levels of prosocial impact. Furthermore, the indirect relationship between abusive supervision and 1) supervisor-directed deviance through justice is significant at high (+1 SD, b = 0.03, CI95 [0.007, 0.082]) but not low levels of prosocial impact (−1 SD, b = 0.01, CI95 [−0.002, 0.036]). Likewise, the indirect effects on 2) supervisor-directed OCB (+1 SD, b = −0.05, CI95 [−0.105, −0.017]) and 3) task performance (+1 SD, b = −0.04, CI95 [−0.090, −0.016]) are significant at high levels of prosocial impact but not at low levels (OCB [−1 SD], b = −0.02, CI95[−0.056, 0.005]; performance [−1 SD], b = −0.01, CI95[−0.045, 0.004]). In all, hypothesis 3 (but not hypothesis 2) is supported.

Figure 3: Study 1 Latent Interaction Plots of the Relationship between Abusive Supervision and Justice Perceptions

Note. Latent conditional plot at high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) prosocial impact. Plotted with recommendations from Muthen and Muthen (Reference Muthen and Muthen2012).

Discussion

The goal of study 1 was to understand how the prosocial impact of a manager influences an employee’s thoughts about and reactions to the manager’s abusive supervision. We tested two competing theoretical perspectives to suggest that prosocial impact can either weaken (via deonance theory) or strengthen (via fairness theory) the negative relationship between abusive supervision and employee justice perceptions and retributive outcomes. The results of this first study support the fairness perspective, indicating that prosocial impact exacerbates the indirect effect of abusive supervision on employee work behaviors. In other words, findings show that the prosocial impact of a supervisor significantly worsens the negative effect of abusive supervision such that employees form stronger injustice perceptions about the abuse and engage in more destructive and harmful work behaviors.

Considering the complex nature of competing hypotheses as well as our moderated-mediation model overall, we sought to conduct a second study with the aim to replicate these findings while using a different research design (e.g., Ferris, Hochwarter, & Buckley, Reference Ferris, Hochwarter and Buckley2012; Köhler & Cortina, Reference Köhler and Cortina2019; McClelland & Judd, Reference McClelland and Judd1993). With a time-lagged study, we again test whether the interplay between prosocial impact and supervisor abuse leads to more destructive employee behaviors or whether “doing good for others” somehow reduces the responses of abuse victims.

STUDY 2

Method

To further understand the effect of prosocial impact on the relationship between abuse and employee perceptions and outcomes, we collected multiwave survey responses from working employees utilizing Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk). MTurk is a platform that many management scholars have used to collect high-quality and reliable data from working employees across the United States (Berinsky, Huber, & Lenz, Reference Berinsky, Huber and Lenz2012; Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, Reference Buhrmester, Kwang and Gosling2011; Schaumberg & Flynn, Reference Schaumberg and Flynn2017; Wang, Restubog, Shao, Lu, & Van Kleef, Reference Wang, Restubog, Shao, Lu and Van Kleef2018; Wee, Liao, Liu, & Liu, Reference Wee, Liao, Liu and Liu2017). All employees were paid $2.60 to complete the surveys and were assured the confidentiality of their responses and that their participation was completely voluntary. The final sample of subordinates was 53 percent male and 77 percent Caucasian; 89 percent had some form of postsecondary education. The most represented industries were retail, education, and finance. On average, employees worked 40.3 hours (SD = 7.1), were 35.6 years old (SD = 9.9), and had 6.2 years (SD = 5.0) of company tenure.

Consistent with study 1, we utilized a CIT to adequately capture employees’ direct thoughts and reactions to mistreatment (e.g., Hershcovis, Reference Hershcovis2011). However, this time, we employed a time-lagged CIT to further improve the rigor and validity of our findings (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2012). Moreover, we attempted to constructively replicate results from study 1 by allowing respondents to write about any workplace incident that they had experienced and not just one from the past twelve months. As follows, at time 1, we asked participants to recall and write about an incident in which they experienced abusive behaviors from their managers (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000). Six hundred employees participated in this CIT and subsequently responded to items measuring abusive supervision, prosocial impact, and justice at time 1. Approximately two weeks later (at time 2), 283 (47.2 percent response rate) of those participants completed follow-up surveys assessing the levels of task performance, supervisor-directed OCB, and supervisor-directed deviance in the time after the abusive incident. Following study 1 and previous research using MTurk (e.g., Wang et al., Reference Wang, Restubog, Shao, Lu and Van Kleef2018; Wee et al., Reference Wee, Liao, Liu and Liu2017), we used attention-check questions to assess the attentiveness of participants (sixty-eight respondents were dropped due to failing these attention-check questions). Additionally, similar to study 1, we dropped those participants who could not write about an incident of abusive supervision (nine respondents), resulting in a final sample size of 206 participants.

Measurement

In an effort to constructively replicate our prior results, we again used an indirect questioning method to counter social desirability of self-reported performance (Dalal & Hakel, Reference Dalal and Hakel2016). Yet, this time, we instructed employees to rate how their coworkers would describe their job performance following the abusive incident. Recall that in study 1, we asked employees to consider how their supervisors would rate their job performance. All other measures and controls were identical to those presented in study 1.

Results

The means, standard deviations, correlations, and internal consistency for all study variables appear in Table 1. As in study 1, we tested the acceptability of our measurement model with CFA. Table 2 shows that our six-factor measurement model fits our data significantly better than alternative models. Furthermore, Table 3 shows adequate discriminant validity as each variable’s AVE estimate was larger than its squared correlation with other variables (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). We again tested our hypotheses with SEM in Mplus 8.

Similar to study 1, we first tested the fit of our structural model without the interaction term. This model has an acceptable fit to the data (χ²[200, N = 206] = 403.67, CFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.10, RMSEA = 0.07). We then estimated the latent interaction model using LMS estimation (Klein & Moosbrugger, Reference Klein and Moosbrugger2000). Consistent with study 1, this current model shows a better fit to the data over the nonlatent interaction with reductions in the AIC and BIC estimators (interaction model, AIC = 11,025, BIC = 11,037; noninteraction model, AIC = 11,028, BIC = 11,040). Furthermore, we utilized a bootstrapping procedure to test our indirect and conditional indirect hypotheses with confidence intervals from five hundred bias-corrected bootstrap samples.

After demonstrating acceptable fit, we proceeded to test hypothesis 1, which described the indirect effect of abusive supervision on 1) supervisor-directed deviance, 2) supervisor-directed OCB, and 3) task performance through justice perceptions. As displayed in Table 4, abusive supervision is significantly related to OCB (ab = −0.07, CI [−0.149, −0.033]) and task performance (ab = −0.05, CI [−0.099, −0.012]) through justice perceptions, fully supporting hypotheses 1b and 1c. However, abusive supervision is not significantly related to deviance through justice perceptions at the 95 percent confidence level (ab = 0.04, CI [−0.001, 0.078]). Instead, it only reaches levels of significance at a 90 percent confidence level (ab = 0.04, CI [0.004, 0.074]). Thus hypothesis 1a receives support at the 90 percent confidence interval level.

We then proceeded to our competitive test of fairness and deonance theory on the role of prosocial impact for the indirect effect between abusive supervision and employee outcomes through justice perceptions (hypotheses 2–3). As theorized previously, the deonance perspective suggested that this relationship would be weaker at high levels of prosocial impact, whereas the fairness perspective suggested that this effect would be stronger at high levels. Demonstrating that there is a moderating effect, Figure 2 shows that the interaction between abusive supervision and prosocial impact on justice perceptions is again significant (B = −0.12, p ≤ 0.05). Furthermore, Figure 4 shows that the direction of the conditional direct effect is the same as in study 1.

Figure 4: Study 2 Latent Interaction Plots of the Relationship between Abusive Supervision and Justice Perceptions

Note. Latent conditional plot at high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) prosocial impact. Plotted with recommendations from Muthen and Muthen (Reference Muthen and Muthen2012).

The results in Table 4 for this study largely replicate those of study 1 and show support for a fairness theory perspective. Specifically, the indirect relationship between abusive supervision and 2) SOCB and 3) task performance through justice perceptions is significantly stronger at high ([SOCB] +1 SD, b = −0.09, CI95 [−0.190, −0.037]; [task performance] +1 SD, b = −0.06, CI95 [−0.138, −0.018]) rather than low ([SOCB] −1 SD, b = −0.04, CI95 [−0.132, −0.008]; [task performance] −1 SD, b = −0.03, CI95 [−0.084, −0.002]) levels of prosocial impact ([OCB], index of moderated mediation = −0.03, CI95 [−0.074, −0.003]; [task performance] index of moderated mediation = −0.02, CI95 [−0.051, −0.001]). Testing 1) supervisor-directed deviance, Table 4 shows that prosocial impact does not moderate the indirect relationship between abusive supervision and supervisor-directed deviance through justice at the 95 percent level (index of moderated mediation = 0.01, CI95 [0.000, 0.041]) because zero is in the confidence interval. However, it does moderate the indirect relationship at the 90 percent level (index of moderated mediation = 0.01, CI90 [0.001, 0.040]). Specifically, this relationship is significant and stronger at high (+1 SD, b = 0.05, CI95 [0.002, 0.109]) compared to low (−1 SD, b = 0.02, CI95 [0.000, 0.059]) levels of prosocial impact. In all, hypothesis 3b and hypothesis 3c are supported at the 95 percent CI level, and hypothesis 3a receives support at the 90 percent CI level. This result largely replicates the results of study 1, where hypothesis 3 but not hypothesis 2 receives support.

Discussion

The goal of study 2 was to once more examine if “doing good for others” helps or harms abusive victims and their organizations. More specifically, we wanted to see if the indirect effect of abusive supervision on employee retaliatory behaviors (through justice perceptions) would be strengthened (as in study 1) or weakened in the presence of supervisor prosocial impact.

Using a different sample and research design (i.e., time-lagged CIT), findings from study 2 replicate those of study 1, reemphasizing that the prosocial impact of an abusive boss creates even greater outrage in employees as illustrated by stronger perceptions of injustice. In turn, these enhanced injustice perceptions foster stronger retributive behaviors such that employees engage in higher levels of supervisor-directed deviance as well as lower levels of beneficial performance behaviors.

Together, these results again confirm the fairness perspective over the deontic approach, showing that the prosocial effects of an abusive supervisor further highlight the inappropriateness of the misconduct via counterfactual comparisons. This, in turn, elicits even stronger retribution in employees. That is, when subordinates see that this very same abusive manager also has the ability to positively impact the lives of others, it becomes even more salient that they should not be treated this way, and they can easily imagine a scenario where the supervisor shows more alignment between various actions (Folger, Reference Folger and Kessler2014; Folger & Cropanzano, Reference Folger, Cropanzano and Greenberg2001). As a consequence, employees perceive strong injustice and seek revenge for what has been done to them.

Considering the support for fairness theory, it becomes increasingly evident that the counterfactual approach, with its alternative scenarios of what appropriate treatment should look like, is critical in generating injustice perceptions and enhancing retribution among employees. However, although we replicated the fairness theory effect across two studies, we did not directly assess the counterfactual thinking that seems to be responsible for driving employee reactions. Therefore we conducted a third and final study to assess the specific thought process that sheds light on why and how the amalgam of positive (i.e., prosocial impact) and negative supervisor (abusive supervision) characteristics elicits revengeful thoughts in victims.

As a reminder, we believe that employees who are faced with mistreatment and prosocial impact by a supervisor are more likely to ponder alternative scenarios that indicate they should be treated differently (Folger, Reference Folger and Kessler2014). As a result, strong injustice judgments occur. Because counterfactual judgments are situation specific (Folger & Cropanzano, Reference Folger, Cropanzano and Greenberg2001), in our context, we argue that these strong negative justice judgments will be driven by the supervisor and the inconsistency between positive and negative behaviors. In contrast, employees who do not face the discrepancy between managers’ abuse and prosocial impact will be less likely to imagine these kinds of better alternatives, where the supervisor has more consistently positive behaviors. In sum, we continue to draw on fairness theory to propose a final moderated-mediation model (Figure 5), in which this specific cognitive mechanism links the interaction of abusive supervision and prosocial impact to employee justice judgments:

Hypothesis 4: Prosocial impact will moderate the direct relationship between abusive supervision and counterfactual judgments such that this relationship will be stronger at high levels of prosocial impact than at low levels of prosocial impact.

Hypothesis 5: Prosocial impact will moderate the indirect relationship between abusive supervision and justice perceptions through counterfactual thinking such that the relationship will be more negative and stronger at high levels of prosocial impact than at low levels of prosocial impact.

Figure 5: Study 3 Theoretical Model

STUDY 3

Method

Given the evidence for fairness theory in studies 1 and 2, we attempted to extend our theoretical model and prior results by depicting the specific cognitive process that ultimately strengthens the retributive work reactions to abusive supervision and prosocial impact. Additionally, we attempted to constructively replicate our results by avoiding the CIT and using a more common correlational recruitment technique employed by ethics scholars (e.g., Dang, Umphress, & Mitchell, Reference Dang, Umphress and Mitchell2017) that entails recruiting working adults through an online classified advertisement across eight US cities. The advertisement directed respondents to an initial prescreen survey with which we verified employment status and eligibility (e.g., at least eighteen years of age, reporting to a supervisor/manager). Following this, respondents were emailed our survey and received four dollars in compensation for participating.

Two hundred nine people completed our survey. We followed similar steps to studies 1 and 2 to ensure the quality of our data. These quality procedures resulted in a sample of 159 employees. Approximately half of these participants were employed in finance, health care, retail, and education. Sixty-six percent of participants were female, and 54 percent were Caucasian. On average, respondents were thirty-five years old (SD = 12.4), had five years of organizational tenure (SD = 6.4), and worked thirty-eight hours per week (SD = 10.7).

Measurement

We utilized the same measures and controls as found in studies 1 and 2, unless otherwise indicated. All measures were rated by the employee. Employees rated abusive supervision, the prosocial impact of the supervisor, their respective justice perceptions, and counterfactual judgments.

Counterfactual Judgments

To measure employees’ counterfactual thinking in regard to their supervisors’ actions, we used Dineen, Lewicki, and Tomlinson’s (Reference Dineen, Lewicki and Tomlinson2006) four-item behavioral integrity scale because it represents the pattern of supervisory actions reflecting the adherence to positive workplace behaviors and avoidance of negative workplace behaviors (Dineen et al., Reference Dineen, Lewicki and Tomlinson2006: 623). This measure allowed us to assess whether respondents imagined possibilities where their supervisors utilized more consistent positive behavior overall. Furthermore, we chose this measure based on the specificity to supervisor behaviors, as counterfactual judgments are situation specific (Folger & Cropanzano, Reference Folger, Cropanzano and Greenberg2001). A sample item is “I wish my supervisor would practice what he/she preaches more often,” and items were measured on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Results

The means, standard deviations, correlations, and internal consistency for all study variables appear in Table 1. Similar to study 1 and study 2, we first tested the fit of our measurement model with CFA and then tested our hypotheses with SEM in Mplus 8. As shown in Table 2, the four-factor measurement model for the items subject to measurement error (i.e., abusive supervision, prosocial impact, counterfactual judgments, justice) demonstrates an acceptable fit to the data. Comparing this model to alternative models (Table 2), this model yields a significantly better fit than other models, and each variable’s AVE estimate (Table 3) is larger than its squared correlation with other variables, demonstrating discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981).

As in the previous studies, our structural model without the interaction term has an acceptable fit to the data (χ²[134, N = 159] = 280, CFI = 0.94, SRMR = 0.07, RMSEA = 0.08). We then estimated the latent interaction model using LMS estimation in Mplus 8. Consistent with study 1 and study 2, this model (AIC = 5,763, BIC = 5,757) shows a reduction in the AIC and BIC information criteria (noninteraction model, AIC= 5,764, BIC = 5,759). Lastly, similar to the previous two studies, we created bias-corrected confidence intervals with five hundred bootstrap samples to test our hypotheses.

Hypothesis 4 suggested that prosocial impact would moderate the positive relationship between abusive supervision and counterfactual judgments such that employees would be more likely to form stronger counterfactual judgments when they also engaged in high levels of prosocial impact. As shown in Figure 6, this interaction is significant (B = 0.09, p ≤ 0.05), indicating that the direct effect was significantly different at various levels of the moderating variable (Dawson, Reference Dawson2014). Furthermore, as Figure 7 demonstrates, the slope for the relationship between abusive supervision and counterfactual judgments is steeper for high levels of prosocial impact. Simple slope analyses further confirm the influence of prosocial impact by showing that the relationship at high levels of the construct is positive and significantly different from zero (+1 SD, b = 1.03, p ≤ 0.001, CI95bcbootstrap [0.609, 1.572]; −1 SD, b = 0.67, p ≤ 0.001, CI95bcbootstrap [0.405, 1.036]). With the relationship being positive and significantly stronger at higher levels of prosocial impact than at low levels, we infer full support for hypothesis 4.

Figure 6: Study 3 Structural Equation Model

Note. Controls are not included to help interpretability. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

Figure 7: Study 3 Latent Interaction Plot of the Relationship between Abusive Supervision and Counterfactual Judgment

Note. Latent conditional plot at high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) prosocial impact. Plotted with recommendations from Muthen and Muthen (Reference Muthen and Muthen2012).

Hypothesis 5 stated that prosocial impact would moderate the negative indirect relationship of abusive supervision on perceptions of justice through counterfactual judgments. As shown in Table 4, the conditional indirect effect is significant (index of moderated mediation = −0.37, CI [−0.298, −0.010]) (Hayes, Reference Hayes2015). Moreover, Table 4 shows that this relationship is negative and significantly stronger at high levels (SD +1, ab = −0.70, CI [−1.10, −0.39]) than at low levels (SD −1, ab = −0.45, CI [−0.70, −0.26]) of prosocial impact. Therefore hypothesis 5 is supported.

Discussion

The aim of study 3 was to understand the specific cognitive process that employees use to make sense of the fact that their abusive supervisor might also be a good person (i.e., has a positive impact overall). In particular, we hoped to identify whether counterfactual judgments are 1) increasingly triggered by the interplay between good and bad supervisor characteristics and 2) responsible for generating strong injustice judgments in employees. Consistent with fairness theory, results show that counterfactual judgments are indeed more likely to occur in this instance and are a key driver of injustice perceptions in victims of abusive supervision.

By extending our model also to depict the cognitive process through which supervisor abuse and prosocial impact influence employee revenge cognitions and motivations, our work continues to extend research on supervisor mistreatment, prosocial impact, and deonance and fairness theory on many fronts. All contributions are discussed in detail in the following section.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Within the vast supervisor mistreatment literature, abusive managers have generally been described as “bad actors,” as they are responsible for many harmful outcomes for employees and organizations alike (Mackey et al., Reference Mackey, Frieder, Brees and Martinko2017; Tepper et al., Reference Tepper, Simon and Park2017). With this current article, we sought to challenge somewhat this unidimensional view by examining how abusive supervisors who also have a positive impact at work influence employees’ perceptions and reactions in the workplace. Looking to theories from the organizational justice literature, we built a competing model that pitted explanations from deonance theory (Folger, Reference Folger, Gilliland, Steiner and Skarlicki2001) against alternative explanations from fairness theory (Folger & Cropanzano, Reference Folger, Cropanzano and Greenberg2001). More specifically, we looked to deonance theory to suggest that employees weigh “doing good for others” as an instrumental factor that would mitigate the negative impact of an inherent, negative violation like abusive supervision. Opposing this view, we drew on fairness theory to posit that a supervisor’s prosocial impact would exacerbate negative judgments and reactions to abusive supervision.

Results across three studies support the latter rationale, demonstrating that the prosocial impact of an abusive boss significantly strengthens injustice judgments in employees, which subsequently fosters many revenge behaviors, including supervisor-directed deviance, reduced OCB, and reduced task performance. As such, these results support fairness theory and its counterfactual assessments as a dominant framework that explains how employees make sense of and respond to bad supervisors who also impact the greater good.

Understanding how employees process and react to managers who concurrently embody good and bad characteristics contributes to the literatures of abusive supervision, prosocial impact, organizational justice, and behavioral ethics in many novel ways. First and foremost, we broaden the scope of abusive supervision research by considering the possible multidimensionality of abusive bosses. That is, we are among the first to consider and show that abusive bosses might not be wholly “bad” people, as they possess and exhibit positive characteristics (i.e., prosocial impact) as well. Furthermore, we found that it is this specific interplay between “good” and “bad” that will ultimately influence how employees experience and react to abusive supervision at work. Indeed, abusive behaviors enacted by managers who also have a positive impact on others elicit even stronger injustice perceptions in employees (via counterfactual comparisons), which further exacerbates retributive acts on the part of subordinates.

By considering supervisor characteristics as a boundary condition, we further extend the mistreatment literature. Given the devastating consequences of abusive behaviors in organizations, scholars have repeatedly turned their attention to exploring the conditions under which these destructive responses are mitigated or exacerbated (e.g., Mawritz, Greenbaum, Butts, & Graham, Reference Mawritz, Greenbaum, Butts and Graham2017). In doing so, however, most work has mainly emphasized victim characteristics (e.g., conscientiousness; Mawritz, Dust, & Resick, Reference Mawritz, Dust and Resick2014) and contextual situations (e.g., deviance of others; Tepper, Henle, Lambert, Giacalone, & Duffy, Reference Tepper, Henle, Lambert, Giacalone and Duffy2008), with little attention put on the transgressing supervisor himself or herself. Here we integrate deonance and fairness theory to suggest (and show) that supervisor characteristics are equally important in driving revenge motivations and behaviors in employees because subordinates interpret and use all supervisor cues to make sense of abusive events. As such, it seems important to broaden the search for moderating variables and increasingly explore supervisory components to more fully comprehend how victims react to abusive acts.

Given the importance of perpetrator characteristics in the study of abusive supervision, our work especially highlights positive factors, such as prosocial impact, as key in helping employees interpret workplace mistreatment and also determine how strongly they might seek retribution afterward. Interestingly, our studies show that “doing good for other people” makes matters worse for victims, as they realize that the abuse is completely out of line. As a result, employees experience even stronger thoughts of injustice, which prompt much stronger retributive behaviors. Taken together, our research introduces prosocial impact as a potent moderator and theory extension in the study of abusive supervision because it directly influences abused employees’ cognitions and, indirectly, their work behaviors.

Because our current findings point to prosocial impact as a critical factor in the abuse model, we also extend research on the concept of prosocial impact. In essence, we show that something so positive as “doing good for others” can, in the wrong circumstance (i.e., when enacted by an abusive supervisor), lead to even more destructive behaviors by the target of abuse. This finding is relevant in a field where past research consistently emphasized the positive outcomes of prosocial impact for employees (e.g., Bellé, Reference Bellé2014; Grant, Reference Grant2007). More so, research even shows that employees attempt to work harder for supervisors who display acts of prosocial impact (e.g., Bellé, Reference Bellé2014). Here we challenge this assumption and demonstrate that good supervisory behaviors do not universally trigger positive work efforts in subordinates. Instead, the presence of prosocial impact in conjunction with abusive treatment can trouble employees and thereby exacerbate many negative reactions.

By the same token, our research also stresses that making a positive difference is not necessarily enough to overpower the effects of abusive supervision or make amends for this bad behavior (as was expected with the deontic perspective). Instead, the interplay between “good” and “bad” behaviors seems to worsen the lives of abuse victims (e.g., Greenbaum, Mawritz, & Piccolo, Reference Greenbaum, Mawritz and Piccolo2015) and further provoke dysfunctional workplace behaviors. As such, these results suggest that prosocial impact (when combined with dark side behaviors) might even act as a catalyst for destructive spirals and lost productivity in organizations (e.g., Porath & Erez, Reference Porath and Erez2009).

The role of prosocial impact is also interesting and enlightening to the deonance literature where scholars predict that positive instrumental factors mitigate the effects of (inherent) transgressions (Folger et al., Reference Folger, Ganegoda, Rice, Taylor and Wo2013; Folger & Stein, Reference Folger, Stein, Cropanzano and Moliner2017). As we are the first to test these deontic tenets in an organizational setting, we indeed found that instrumental factors (i.e., doing good for others) influence how employees view and react to moral transgressions (Folger et al., Reference Folger, Ganegoda, Rice, Taylor and Wo2013; Folger & Glerum, Reference Folger, Glerum, Cropanzano and Ambrose2015). However, the direction of the relationships is counter to what deonance theory predicts, indicating that the instrumental component further harmed employees and their organizations. These findings challenge deontic assertions, offer new insights to scholars within this field, and call for future research to delve more deeply into these premises.

Finally, our work conjointly contributes to the abusive supervision, organizational justice, and behavioral ethics literature by using deonance and fairness theory as competing rationales to understand how employees view and react to abusive supervision.Footnote 6 In his review, Tepper (Reference Tepper2007) called for a stronger theoretical rationale beyond social exchange or interpersonal justice frameworks. Recent reviews have also echoed this call (e.g., Mackey et al., Reference Mackey, Frieder, Brees and Martinko2017). In this current article, we employed a competitive perspective to carefully unfold each link and mechanism that explains subordinates’ reactions to multidimensional supervisors in the workplace. In support of fairness theory (Folger & Cropanzano, Reference Folger, Cropanzano and Greenberg2001), we find that victims of mistreatment increasingly turn to counterfactual thinking when they are confronted with good and bad managerial characteristics. In turn, this cognitive process triggers stronger injustice perception and retributive behaviors, both of which harm the employee, the supervisor, and the organization.

Practical Implications

Beyond its theoretical implications, our research is relevant to organizations and practitioners for a variety of reasons. First, organizations should recognize that prosocial behaviors do not atone for harmful supervisory actions like abusive supervision. Thus companies might want to consider termination as one possible recourse even for those abusive supervisors who engage in prosocial behaviors. However, there are other contingencies that companies should take into account before making termination decisions. For example, organizations can first try to limit the occurrence of negative behaviors altogether (thereby also mitigating negative outcomes). Companies should maintain clear guidelines of what is appropriate and expected behavior (e.g., Miner-Rubino & Cortina, Reference Miner-Rubino and Cortina2007). Finally, we emphasize the importance of promoting and maintaining an overall ethical workplace. Positive workplace climates (including ethical work environments) can help reduce deviant or negative behaviors (Martin & Cullen, Reference Martin and Cullen2006), such as abusive supervision. By creating a broader climate focused on ethical actions, organizations can reduce abusive acts by supervisors. However, if supervisors still remain unreceptive to changing their behaviors after all these undertakings, the organization may consider ending the employment relationship at that point.

Second, our results indicate that organizations and those in management should be cognizant of how subordinates respond to supervisory behaviors. That is, supervisors are not unidimensional and are neither wholly good nor bad (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Ma and Johnson2016), and organizations should remain aware of how multiple behaviors impact employees when training supervisors or evaluating their performances. Furthermore, as the specific interplay between abusive actions and prosocial impact seems to particularly harm employees and departments via continued revenge behaviors and destructive spirals, organizations should stress the need for behavioral integrity and the necessity of consistency in exhibiting positive, and not negative, behaviors, as those have been found to create positive work outcomes (e.g., Simons, Reference Simons2002).

However, given the complex nature of organizations, it might be that misalignment of supervisory actions (i.e., displaying both positive and negative behaviors) can still occur in organizations (Effron, O’Connor, Leroy, & Lucas, Reference Effron, O’Connor, Leroy and Lucas2018). If that is the case, research has suggested that practitioners increase their focus on minimizing the negative outcomes of this inevitable misalignment (e.g., Effron et al., Reference Effron, O’Connor, Leroy and Lucas2018). We believe that organizations should take care to educate leaders on how their employees perceive them when their workplace behaviors provide mixed signals. With this, companies should anticipate misaligned behaviors and prompt supervisors to engage in authentic reparative actions when they do occur. That is, they should not try to minimize negative actions by engaging in prosocial behaviors but rather should actively pursue reparative actions. For example, managers who respectfully apologize to subordinates after engaging in bad behaviors might be able to restore justice perceptions in employees and thus minimize any negative fallout (De Cremer & Schouten, Reference De Cremer and Schouten2008). In addition to apologizing privately to a victim, managers could also use a more public approach and admit their wrongdoing in front of other employees. Lastly, managers may consider a restorative justice approach where they give victims and other stakeholders a voice in proposing actions for the offender to take in making amends for the transgression (Goodstein & Butterfield, Reference Goodstein and Butterfield2010).

Limitations

Despite the strengths of our study, we acknowledge certain limitations that should be considered when interpreting our findings. First, our results might have suffered from various forms of response bias. The cross-sectional nature of the data in study 1 is susceptible to common method variance (CMV). To combat this, we incorporated several recommended techniques (e.g., assuring respondents that there were no right or wrong answers and reminding respondents of the value of the scientific process; Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003). Furthermore, interactions are immune to CMV (Siemsen, Roth, & Oliveira, Reference Siemsen, Roth and Oliveira2010), and these are at the heart of our analyses across each study. Scholars (Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie and Podsakoff2012; Siemsen et al., Reference Siemsen, Roth and Oliveira2010) have concluded that if an interaction effect is found, it shows convincing evidence that CMV did not present a bias. Furthermore, we took more robust steps in other studies (i.e., using a time-separated design; Podsakoff et al., Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003).Footnote 7

A second weakness concerns the use of critical incident techniques. Some scholars have noted problems of recalling events in the past (Thomas & Diener, Reference Thomas and Diener1990), which might lead to imprecise representations of the underlying relationships. However, many scholars have successfully utilized this survey technique (e.g., Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Vogel and Folger2015) and noted that it is effective in studying perceptions of and responses to mistreatment (e.g., Bobocel, Reference Bobocel2013). Additionally, we utilized an alternative survey design for our study 3.

A third weakness of this article is that we were unable to test our full serial moderated-mediation model in study 3. Together, studies 1 and 2 and study 3 show evidence that supports our full model, but this was not explicitly tested. We note that the effects of our last (serial) link between justice and retributive outcomes are well supported in past research (e.g., Colquitt, Reference Colquitt2001). Thus we can likely infer this relationship in our study 3 as well.

Finally, we acknowledge that there could be potential alternative explanations for our findings that prosocial impact worsens the relationships between abusive supervision and supervisor outcomes. For example, the combination of abusive supervision and prosocial impact could create role confusion and stress for the employee such that the employee does not know what is expected from him or her in the employee’s own role or how he or she will be treated (e.g., Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, & Rosenthal, Reference Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek and Rosenthal1964). Our model offers advantages over these other explanations, though, as we competitively test tenets from two justice theories, replicate findings across studies, and assess the predicted mediating mechanism in the third study. Additionally, we note that our theoretical model fits with prior explanations and is complementary to the literature (e.g., Mackey et al., Reference Mackey, Frieder, Brees and Martinko2017; Tepper, Reference Tepper2007; Treviño, Weaver, & Reynolds, Reference Treviño, Weaver and Reynolds2006). However, future research might focus on further ruling out alternative explanations.

CONCLUSION

This article examined how employees respond to abusive bosses who also have a positive impact on others at work. Drawing on deonance and fairness theory, we proposed competing hypotheses that suggest a supervisor’s prosocial impact could either further harm or help victims of abuse. Across three field studies, we found support for fairness theory, indicating that employees are much more revengeful when the abusive supervisor also makes a positive difference at work. By uncovering the effect of a supervisor’s prosocial impact on employee reactions to abusive supervision, this article contributes to the research on supervisor abuse, prosocial impact, organizational justice, and behavioral ethics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Folger and acknowledge his helpful comments in the preparation of this article.

Michael A. Johnson is the Olinde Professor of Management and an assistant professor of management in the E. J. Ourso College of Business at Louisiana State University. His research concerns business ethics, diversity, and job search. His work has been published in management journals including the Journal of Applied Psychology and the Journal of Business Venturing.

Manuela Priesemuth is an associate professor of management in the Villanova School of Business at Villanova University. Her research interests include destructive leadership, workplace aggression, behavioral ethics, and organizational justice. Her work has been published in management journals including the Academy of Management Journal, the Journal of Applied Psychology, and the Journal of Management.

Bailey Bigelow is a PhD candidate in the Department of Management at the University of Central Florida. Her primary areas of research are employee unethical behavior and workplace mistreatment. More specifically, her research projects take an actor-centric or third-party observer approach to understanding the full effect of workplace mistreatment on members of the organization. She has published her work in journals such as the Journal of Applied Psychology.