INTRODUCTION

In the final years of Zimbabwe's liberation war, Cuban and Soviet instructors stationed in Angola trained over six thousand ZIPRA (Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army) soldiers. According to Jorge Valdes Risquet, head of the Cuban civilian mission in Angola, this was “possibly the largest school of this kind in the world.”Footnote 1 By the end of the war, the Angolan-trained groups constituted close to a third of ZIPRA's forces,Footnote 2 and would prove vital to the introduction of conventional tactics in the guerrilla war fought by the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) against Rhodesia's settler government. Forty years later, these Angolan-trained men retained a strong sense of their military identity. They held that their training had made them a formidably fierce, technically advanced fighting force with a particular idea of revolutionary warfare summed up in the Cuban cry “Adelante!” (Forward!). This military vision had set them apart, they said, from other ZIPRA cadres, and sometimes brought them into conflict with them. Despite its significance in the past and in the present lives of veterans, the experience of these men is little more than a footnote in studies of the Cold War in the region and barely features in Zimbabwe's liberation war history, which has been dominated by ZAPU's counterpart, the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU), the eventual victor in the country's postwar elections.Footnote 3

International military training powerfully shaped every southern African liberation movement, but the nature of these military exchanges, even for the victors, has rarely been subjected to close scrutiny. We explore the genesis and effects of Adelante! in ZIPRA's war in order to begin to write the complex histories of such Cold War-era military exchanges. In doing so, we adapt the concept of “military imaginaries” developed by Andrew Bickford in his study of soldiers in the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and their experience of German reunification. In Bickford's account, the military imaginary is produced by the state: it encompasses “the ways in which the necessity, implementation, and desired outcomes of (compulsory) military service and training are imagined and envisioned by the state, and the ways in which these tropes are linked to normative ideas of the “proper” soldier and man, legitimate violence, morality and military tradition.”Footnote 4 The role of the state is overweening: as he puts it, “the soldier is the state,” even if the memories and histories of the state and soldier are rendered contentious by political change.Footnote 5 In identifying the soldier with a state project, Bickford carries forward a major theme in the study of conventional militaries across the globe.Footnote 6 But what happens when there is no state to anchor the military imaginary?

The liberation movement armies that fought Southern Africa's intransigent settler states were based in military camps in exile and were loyal to nationalist political movements that certainly dreamed of a state but did not have one. In the 1960s and 1970s, these movements depended on political relationships with “hosts” among the newly independent African states to their north, mediated by the nascent regional organizations of the Frontline States and the Organization of African Unity. More distant powers, notably Eastern Bloc states but also Cuba, India, China, and others, offered military training and other kinds of support under the rubric of international solidarity. In the case of ZAPU, cadres were trained in Ghana, China, Egypt, Algeria, Cuba, North Korea, the USSR, GDR, Bulgaria, Romania, Yugoslavia, Ethiopia, Somalia, Libya, and even Lebanon (where a small group of ZIPRA men trained and fought with the Palestinian Liberation Organization [PLO]), in addition to the major military camps in Tanzania, Zambia and Angola. In these latter, instructors came from within ZIPRA, the Zambian army, Cuba, the USSR, and elsewhere.Footnote 7 Within such liberation movement armies, a multitude of military imaginaries were thus constructed, tested, discarded, or allowed to co-exist over time.Footnote 8

The regimes under which the Cold War-era training of liberation movements took place was thus a far cry from the disciplinary oversight provided by a single state. This complexity helps to explain the deep tensions that bedeviled all liberation movement armies, as well as the nature of the wars they fought and soldiers’ memories thereof. Exploring their military imaginaries allows us to make several broader arguments. First, we bring to light a crucial aspect of Cold War-era exchange that scholars have neglected—military training—and thus add a new dimension to the burgeoning work on both the “global” Cold War and the transnational character of southern African liberation movements.Footnote 9 Within the latter literature, we add a new element to the rich debates over the role in the making of liberation movements of “the camp.” Scholars have focused on everyday life and political and social relations within camps located largely in Angola, Zambia, and Tanzania, and often cast them as spaces in which repressive authority was made and contested.Footnote 10 Few studies examine the making of soldiers per se, however, thus obscuring enduring military identities.Footnote 11 Second, highlighting liberation armies’ plural and political military imaginaries adds a new dimension to scholarship on military training itself. Liberation movement armies clearly differed from the conventional state militaries that have dominated debates over training and its effects. They also differed from the armies discussed under the rubric of “new wars” and other forms of post-Cold War insurgency. These rebel movements, which also produced military imaginaries beyond the reach of a state, developed modes of training that were usually far more dispersed, localized, and informal.Footnote 12 While backing from external states often mattered in “new wars,” the scale and duration of military assistance received by Cold War-era liberation movements and the politics of internationalist solidarities were distinctive. Liberation armies’ experiences of training thus tell us about the making of highly unusual militaries at a particular historical moment.

Before turning to ZIPRA's story, we consider how the study of military training has been approached in recent scholarship and set out our own methodology.

MILITARY TRAINING AND SOLDIERS’ ORAL HISTORIES

Training occupies a central place in scholarship on militaries, both in longstanding strategic and technical approaches to war and in the newer field of critical military studies. These studies are marked by a division between a “conventional war scholarship,” in which soldiers are cast as elements to be deployed in a fighting force, the efficiency and efficacy of which is the main concern, and a focus on “lived experiences,” embodied practices and emotions, framed within critical approaches to state and society.Footnote 13

The first tradition of writing tends toward instrumentalist accounts of training. The historian Hew Strachan, for example, locates the value of training in its capacity to counter boredom, generate professional pride and “unit cohesion,” and enable soldiers to master technology and “assimilate new tactical thinking to the point where it becomes instinctive in its application.”Footnote 14 Similarly, the military sociologist Dan Snider has characterized the “military culture” produced in training as the “glue” that holds units together. Officers’ socialization of soldiers, he argues, works by cultivating shared values, norms, and expectations able to shape “attitudes and behaviors about what is right and what is good and important, often manifested in shared heroes, stories and rituals that promote bonding.”Footnote 15 Historians of colonial armies such as Tarak Barkawi have argued that military training was the essential element in creating “group solidarity” within otherwise highly diverse armies, such as the Indian Army in the Second World War.Footnote 16

The second tradition stresses the power of training, too, but foregrounds soldiers’ responses to and perceptions and memories of military regimes, often using ethnographic methods or relying on soldiers’ written and oral accounts. Training is explored in relation to the emotional and embodied aspects of military hierarchies, masculinities, and social identities, and their connection to citizenship, ideology, and societal militarization.Footnote 17 This strand of writing is concerned with state projects of “control and transformation” as well as soldiers’ responses to them.Footnote 18 In her study of British conscripts in the Second World War, for example, Emma Newlands scrutinizes soldiers’ stories, memoirs, letters, and diaries and finds a variety of public and private tactics of resistance: “the body,” she writes, “was difficult to control and to be controlled. Ultimately, it was an unstable object for power.”Footnote 19

Both strands of scholarship have shaped our approach to ZIPRA soldiers and to the military imaginaries fostered among them through training. ZIPRA veterans’ accounts oscillated between these two ways of talking about military training and their lives as soldiers, an ambivalence that marks soldiers’ stories in other contexts, too.Footnote 20 On one hand, they often used technical and strategic language to recount the effects, rationale, and relevance (or otherwise) of components of training and, in so doing, often repeated and reflected on the views and arguments of their instructors. Indeed, discussions of expertise and efficacy formed an important aspect of soldiers’ stories. At the same time, veterans offered reflections on their military experiences that explored murky moral and emotional terrains, at times indicating a tension between their belief in the necessity of the hierarchies and discipline that were almost always central to military training regimes and their experience of these regimes as cruel or unjust.

We rely on oral histories partly owing to the lack of other sources, but more importantly because they provide a unique vantage point that allows us to engage these complex views on military training. We approached veterans with the assistance of several key interlocutors with whom we have worked for several decades: the historian Pathisa Nyathi, and Zephaniah Nkomo and Zephaniah Moyo, both former ZIPRA combatants who are involved in veterans’ organizations based in Zimbabwe's second city, Bulawayo. They are well known within veterans’ circles and are identified with different views and groupings across this diverse community. Through their connections, we spoke to eleven men about Cuban training. They had been teachers, factory workers, labor migrants to South Africa, or school kids before joining the struggle in Zambia. Some spent years in Angola, staying on as instructors or for specialized training, while others returned to the warfront after the standard six-month training stint. They had traveled different paths after independence, as well, some serving in the Zimbabwe National Army and others returning to civilian roles. Despite these differences, they shared a passionate sense of grievance regarding what they saw as the ruling party's marginalization of ZIPRA's war history in favor of its own. The result was, in their view, a distorted victor's history born of the tensions of the war itself and reinforced by the post-independence state violence of the 1980s in which ZAPU and ZIPRA cadres had been subjected to a lengthy campaign of detention, torture, and killings. This shared grievance did not, however, produce a monolithic “counter-history.” The period in which we undertook our interviews was marked by the regular publication in the Zimbabwean media of interviews with ZIPRA cadres (some of which we draw on here), which sustained lively debates among these now elderly men.Footnote 21 ZAPU's war history is living, public, and constantly contested both within ZIPRA and between it and its opponents, past and present. For all of these reasons, ZIPRA cadres told stories of their heroism and military sophistication but also invoked more ambivalent, discordant, and particular memories.

The stories of this cohort of Angolan-trained ZIPRA veterans brought to light aspects of military life we had not previously grasped. In our earlier work on ZIPRA, we had argued that soldiers’ narratives were structured as stages on a journey, marked by the crossing of rivers and borders and the survival of ordeals.Footnote 22 Becoming a ZIPRA cadre was widely told as a story of achieving military professionalism, expressed in the mastery of weaponry, nature and fear, rigorous discipline, and a political understanding of the war as a struggle against an exploitative “system,” not simply a racial enemy.Footnote 23 Being “professional” stood at the heart of ZAPU soldiers’ military imaginaries in these accounts, and was constructed in opposition to ZANU's armed wing, which was parodied as a barely trained rabble. While the Angola-trained soldiers’ oral histories echoed this broad narrative, delving into training itself in the context of a wider set of lively debates about ZIPRA's history raised questions beyond the generic notion of the professional soldier, revealing discrete military imaginaries that had co-existed within this army and powerfully shaped its conduct and legacies.

As we have noted, the variety of military imaginaries in ZIPRA was produced in great part by the movement of cadres through numerous camps and the hands of different instructors. As with almost all ZIPRA soldiers, the Angolan-trained cadres started their military lives in the Zambian camps, a formative moment that would begin a lengthy process of transformation.

ENCOUNTERING MILITARY LIFE IN ZAMBIA

First encounters with military life, often in the form of “basic training,” loom large in soldiers’ memories. As McSorley writes, basic training constitutes “the classic site of militarisation,” where military values, hierarchies, and automated corporeal repertoires are first inculcated into civilians.Footnote 24 Writing about Bolivian conscripts, Lesley Gill casts basic training as “a gendered process of moral regulation” that “subordinates individuality to the identity of the male group and instills rigid conformity and compliance to military values,” often in violent and abusive ways.Footnote 25 Gutmann and Lutz, writing about American marines, similarly stress the physical and emotional violence of basic training. One of their interviewees described it as a means through which “they break you down into a big ball of clay” and then introduce new forms of discipline through drill.Footnote 26 Soviet basic training has likewise relied on systems of subordination and violence, coupled with political surveillance.Footnote 27

Basic training is intended to produce military forms of discipline; it also displaces prior understandings of soldiery and societal myths about war in ways that reflect distinct historical and institutional contexts. For conventional armies, the key instigator of change in this regard is state politics and practice.Footnote 28 In the case of ZAPU's war, it was the camps themselves. While hardships and harsh discipline were common across southern African liberation movement camps, their practices also reflected particular histories and so took distinctive forms.

In the second half of the 1970s, ZAPU's camp regime faced new challenges owing to the rapid escalation of the war. ZIPRA's main site of induction for new arrivals was Nampundwe camp, one of a fast-expanding network of ZAPU camps in Zambia. Most of our interviewees arrived at the camp in 1976 and 1977, at the moment of a great surge of young people into Zambia. Brickhill estimates half of all ZIPRA recruits arrived in 1977 alone.Footnote 29 In this context, ZAPU struggled to meet logistical and security demands while fears of infiltration spread, a situation greatly exacerbated in 1978 when the Rhodesian Air Force carried out a devastating series of bombings of the camps. A heightened concern for discipline, loyalty, and fitness among Nampundwe's instructors flowed from these conditions, as well as from two additional factors. The first was the influence of a longer transnational history of the camps. Many of the key figures in Nampundwe's administration had had what they described as traumatic experiences of violent clashes between ZANU and ZAPU cadres in guerrilla training camps in Tanzania (the outcome of failed efforts to unify the two movements on the part of their host governments). These experiences had convinced them that “strong training,” able to produce fitness, discipline and an unshakeable political loyalty, was necessary for the survival of both ZAPU itself and the new recruits.Footnote 30 The second factor was camp instructors’ awareness of the new demands created by shifts in military strategy. They wanted to produce men who were “trainable” subjects for the foreign militaries around the world to whom they were now sending thousands of young men. In the words of Cetshwayo Sithole, an influential instructor at Nampundwe, their international supporters could not be offered “the indiscipline of an untrained unit.”Footnote 31

The pressures that had produced the basic training regime in Nampundwe were unknown to the young men and women who had set off from Zimbabwe to join the armed struggle. In common with many arrivals of this era, our interviewees described having set out on the circuitous route to Zambia after being caught up in the “spirit of war” as news of fighting spread and they encountered guerrillas directly or heard tales of them. Some had family histories of nationalist activism and were urged to join by older relatives or had themselves been involved in protest and sabotage as members of ZAPU's youth wing. Many were motivated by the calls to cross the border broadcast on ZAPU's radio transmissions from Zambia, notably those by the legendary Jane Ngwenya. Whatever their motivation, their understanding of what would happen on arrival in Zambia was a far cry from the reality. Most explained that they had expected a rapid turn-around, an expectation shared by new arrivals across all liberation movements: “We just thought maybe when we get there we will be given guns on the same day,” Ndaba Maqeda remembered.Footnote 32 In an interview in 2017, Jane Ngwenya recalled the many complaints of the young men who had responded to her call to “get the gun and go back to fight” only to be “shocked to find out that they were to undergo a rigorous military training exercise before taking the gun.”Footnote 33

Veterans identified the induction ritual at Nampundwe, known as “meeting the old man,” as the moment when their civilian understanding of war was displaced by something hitherto unimaginable, in an echo of many soldiers’ tales of the prior “unknowability” of military worlds.Footnote 34 “Meeting the old man” was intended by the camp's instructors to do precisely that. Cetshwayo Sithole recounted designing a “welcome” that “introduced you into a system, a system that will make you know that you are in a war zone”: it was meant to “mold” the recruit “into a formation that is controllable.”Footnote 35 New arrivals at first understood the “old man” to be ZAPU President Joshua Nkomo, a fatherly figure of heroic proportions who had recently been released from detention and gone into exile: it made sense that he would warmly welcome them. What came next was remembered as a terrible shock. Green Mpofu, previously a machinist in a Bulawayo factory, recounted how he and his group had arrived at the camp filled with “excitement,” believing they were “already part of the struggle.”Footnote 36 On their first night, they were taken aback by the lack of blankets, the filth, and the “thousands of people … milling in all directions.” The next morning, they were told they were “going to meet the old man, Nkomo” on a nearby rocky hill. Mpofu remembered men rushing to put on their best attire in giddy anticipation. Once at the hill:

Things went topsy turvy, upside down. When we got there, it was tough.… Right, crawl, go down, crawl, roll, crawl. There was no time to say, no these trousers are special or what. Things got out of hand…. There was no time to pity anyone. We rolled, crawled, others [were] vomiting…. [It's] difficult to describe. We couldn't imagine this, we were being conditioned…. I became extremely thirsty … and asked “Can I have a drink.” I still remember the laughter which he [the instructor] emitted: “This one here is saying he wants water!” Go down, crawl. It was as if I'd insulted him by asking for a drink.… It was an introduction to the system. That was the initiation. It was said we'd met the old man. That was the meeting.Footnote 37

These tales of “meeting the old man” were often recounted with dark humor, at the destruction of the fine suits foolishly donned to impress Joshua Nkomo, or in the memorable obscenities of the instructors whose language was “just a bag of insults.”Footnote 38 But “meeting the old man” stood out in veterans’ accounts above all as a story of their shocking subjection to an authority that claimed power over bodies and emotions without sympathy. As Bonus Hlabangana put it, “We cried, we were kicked.”Footnote 39 “Everyone then knew it was war,” recalled Jabulani Sibanda.Footnote 40 This moment delineated a militarist control and masculinity that echoed those of state militaries, but which was produced here by the regime of liberation movement camps.Footnote 41

The lessons of this “welcome” were, in veterans’ stories, reinforced in the course of daily training regimes in which dissent was equated with treason, non-military solidarities among recruits (the bonds of home such as ethnicity, region, kinship, or friendship) were targeted and sundered, and individuals’ expendability was made clear in the use of severe corporal punishment.Footnote 42 This regime shattered some men's sense of justice and mutual obligation, leaving them with uncomfortable memories. Green Mpofu recounted an incident of collective punishment, meted out following a minor incident of theft. He had not participated in the theft, but his protests only earned him an accusation of treason. His fellow recruits from home felt unable to defend him for fear of being accused in turn. Mpofu counted himself lucky to have survived his physical punishment. He explained: “Before you understand military discipline, you think you can resist certain things. You don't appreciate.” Mpofu's terrible story was followed by an ambivalent rationalization. He circled between his ongoing sense of injustice and his soldier's understanding of the requirements of war: “That situation, it still rankles. I'm not bitter about it—I understood it was guerrilla war.… The reason was military discipline and security. If they compromised on such issues, they'd lose a lot of people. So, I understood that. But it was really a bitter experience.”Footnote 43

Ambivalence about this initial period of training was also owed to the more positive and political elements of training, which lightened the lessons in bodily and emotional discipline. These elements shared the purpose of creating powerful attachments found in state militaries,Footnote 44 but took a form that reflected the context and nature of a liberation struggle. A universal aspect of induction was the process of screening new recruits and taking down their biographies, measures intended in part to identify “sellouts,” and the allocation of war names by which they were known henceforward. War names were a marker of inclusion in ZIPRA, a means of securing the safety of recruits and their families by rendering them unrecognizable to the Rhodesian state. They were also a way of distancing young men from regional and ethnic identities, and so placing loyalty to the imagined nation and ZAPU first.Footnote 45 Nampundwe was often also the place where recruits had their first political lessons, gaining a new, shared clarity regarding the purpose of the struggle. Bonus Hlabangana, a former schoolteacher, remembered classes on the ZAPU Manifesto and socialism: “We didn't know much about that, we only knew capitalism, about America. We didn't know much about the Soviet Union, Cuba, and so on. So, we were told about all the eastern countries.”Footnote 46 Nico Ndlovu, who described himself as part of an “erudite group,” recalled a library at Nampundwe with books from the “USSR, Hungary, Cuba, and elsewhere,” covering history, politics, and ideology. He walked around the camp with “a book tucked in my belt.”Footnote 47

An additional aspect of military training at Nampundwe was the inculcation of pride in physical fitness that merged an ideal of manhood with that of the soldier. Young men's bodies were transformed through daily exercises, runs, and drills.Footnote 48 Among these exercises was the ubiquitous toyi-toyi, a high-kneed run accompanied by song and chant that had been introduced to ZAPU in the Algerian training camps of the 1960s. This was an internationalist military performance par excellence, but it had been remade to serve ZAPU's need for nationalist unity and loyalty in the face of division.Footnote 49 The toyi-toyi was performed across all of ZIPRA's camps, serving as one of the recognizable “glues,” to use Snider's term, that held this army together. The men we interviewed emphasized both the harshness of their physical training and their pride in their fitness. They noted how it had impressed the Cubans and Soviets when they arrived in Angola, and compared themselves favorably to other liberation movements, notably the ANC and ZANU. Only the PLO, they maintained, had a physically tougher training regime, a mythology reinforced by the storied careers of the handful of ZIPRA men who had trained in Lebanon and who had themselves become instructors and commanders.Footnote 50

Basic training at Nampundwe displaced the ideas about soldiery and war that these young men had brought from home with a new, substantial military imaginary, forged in and from the transnational history and practices of the camps. For veterans recounting these experiences decades later, this passage was vividly recalled as marking the start of their understanding of what a “proper” soldier was. The idea of getting a gun to fight white settlers was replaced with an understanding of the necessity of subjecting bodies, emotions, and alternative solidarities to a hierarchical, political military authority. This did not, however, satisfy the “spirit of war” that had brought these young men to Zambia and it did not create fully obedient military subjects, despite the harshness of the disciplinary regime. This was not least because these liberation movement camps were large and chaotic. They operated to a great extent autonomously from the Zambian state and were permeated by the possibilities offered by internationalist solidarity.

The men we interviewed said that when news began to spread of the arrival of Cubans in the Zambian camps they saw in them the route to the battlefield that they craved. In Piero Gleijeses’ account, the first Cuban-manned column of Soviet trucks left the Angolan capital Luanda laden with supplies, made the 4,622 kilometer trek to Lusaka, and then quickly turned around with over two thousand ZIPRA cadres on board and headed for Boma in North-Eastern Angola.Footnote 51 In veterans’ accounts, the process was considerably more messy. A surprising number said they had in effect selected themselves for training.Footnote 52 Mark Mbayiwa, a skilled factory worker from Bulawayo, was working as an electrician in Freedom Camp when the group going to Angola gathered there: “I said, no, I can't stay. I must run and join them.” When the trucks arrived, he recounted, “I just joined without telling anyone!”Footnote 53 The fifteen-year-old schoolboy Charles Makhuya, due to be sent to a camp for those too young to fight, likewise jumped into a truck. He remembered: “The Cubans loved us, as youngsters, [they said] come inside!”Footnote 54 Henry Jabulani Sibasa had been deployed in intelligence work at Nampundwe as part of a platoon that took down new arrivals’ biographies. This was in his view a “civilian job” and he “wanted to go fight.” His entire platoon jumped into a nighttime convoy of trucks, using their “influence” as intelligence cadres to silence the drivers’ objections.Footnote 55

The stories of the journey to the Boma camp, where these men would be the guests of Angola's MPLA government, depict a passage into a shocking landscape of war. Most of the first recruits made the trip packed in the backs of Soviet-made KrAZ trucks, a vehicle whose noise and discomfort peppers veterans’ accounts. The journey usually took five to six days and traversed regions that had seen heavy fighting among a host of armed groups, and was itself a terrifying lesson in war and its international, chaotic character. These groups included the armies of the MPLA and its opponent UNITA in Angola, the separatist Katangese gendarmes in Zaire's border zones, and shadowy rebels in northern Zambia.Footnote 56 Ndaba Maqeda was part of an advance party of three hundred that took fourteen days to arrive in Boma, traveling via what was then Zaire. He remembered that it was “hot” in Zaire because of the “Katangese.” Their first task on arrival in Boma was “to clear Savimbi [UNITA] from that area.”Footnote 57 Brian Hlongwane recalled the Cubans searching for insurgents in Zambia: “That's when I realized how serious they were from a military point of view.”Footnote 58 Charles Makhuya told of a landscape marked with “old and empty buildings”: “We were shocked! You could see the bullet holes, marks, where the fighting had been taking place.”Footnote 59

These unnerving passages delivered these young men to Boma, underlining the sense of distance between the social and military world of Nampundwe and what was to come. They were about to enter another liberation movement camp, in this instance run by Soviet and Cuban advisers and instructors who brought their own military expertise, traditions, and internationalist politics. It was in this environment that our interviewees took on the military identity that would last a lifetime.

THE SOVIET AND CUBAN REGIME IN BOMA CAMP

Angolan-trained ZIPRA veterans looked back on the material conditions and spatial order of Boma camp with far greater warmth than they did Nampundwe. Their memories also differ markedly from the negative or civilian-oriented images of “the camp” in studies of southern African liberation movements generally. They described a regime of order and care alongside a set of military exchanges, both of which were rooted in an appealing, militarized version of internationalist solidarity that they credited primarily to their Cuban instructors. We will first discuss the institutions of order and care offered in Boma before turning to military training proper, the powerful military imaginary it produced, and the ways in which it would reshape this army and war.

The possibility of creating a more positive environment for training in ZAPU's Angola camps as compared to those in Zambia was in part owed to their smaller scale, distance from the warfront, and clear goal: preparing men to fight. The vast complex of ZAPU's Zambian camps was home to tens of thousands of refugees, children, women, new recruits, and peripatetic battle-tested soldiers, all within reach of Rhodesian attack. Boma's trainees were all young and male and Boma's remote location outside the town of Luena (formerly Vila Luso) insulated it from the Zambian rumor mill and the sometimes-divisive machinations of ZAPU's political and military leadership, as well as, initially, from Rhodesian attack. Boma's command structure was remembered as clear cut: at the apex were Soviet officers and the ZIPRA liaison officer and political commissar.Footnote 60 The Soviets supplied the weaponry and uniforms while the much larger number of Cubans took charge of security and logistics, including preparing the camp, providing food and water to its inhabitants, and undertaking the bulk of military instruction. The Cubans, not the ZIPRA or Soviet leaders, were the main point of contact and source of authority for men in Boma. A second, smaller camp, known as Luso, was run directly by Soviet officers and focused on training tank, armored car, and amphibious vehicle crews.Footnote 61 Our interviewees emphasized that the clarity of the military hierarchy was reinforced in the physical layout of the camps. The Cubans and Soviets were housed separately from the trainees and they drank in separate spaces, underpinning their authority with physical and social distance.Footnote 62

In Boma, the roughly two thousand ZIPRA trainees present at any given time were divided into twelve companies, each with its own command structures and “barracks,” rows of long sheds without walls where cadres slept in hammocks.Footnote 63 Veterans remembered Boma's conditions as a great, and deeply appreciated, improvement on Nampundwe. Brian Hlongwane contrasted his “very, very comfortable” hammock with his experience of sleeping on the ground in Nampundwe, where one's blanket might be stolen in the dead of night.Footnote 64 Green Mpofu painted a vivid picture of his humanity restored by Boma's material conditions: “[In] Nampundwe, sanitation was a problem…. The amount of lice which each comrade had, right from the head, into the seams of the trousers, all lice. When you parade, you weren't allowed to scratch—it was said this louse is your comrade, don't scratch! So, when we got to Angola, we were in tatters all of us, tatters. The Cubans were organized for that. We had to throw away all those tattered things and got new clothing, boots, razor blades to shave our heads. We became human again.”Footnote 65

Uniforms, razors, and hammocks did not, however, mean an end to physical hardship. Quite the opposite, since developing the capacity for bodily endurance was at the heart of the Cuban regime. This capacity was strongly associated with food. The Angolan trainees took on the nickname bafana we gapha—“the boys of the tins”—a reference to the notoriously meager rations of rice and beans the Cubans cooked and measured out in small tins. Trainees remembered becoming “very thin”; they recalled lodging complaints, and even writing to Lusaka, about the small portions and specifically the absence of the maize porridge that formed the Zimbabwean staple and which they considered essential to well-being.Footnote 66 Our interviewees did not, however, cast the Cuban food regime as a sign of a dearth of supplies or a lack of care. Instead it was portrayed as a military diet intended to create a lean body able to endure the physical demands of war. Mark Mbayiwa held that the Cubans “didn't believe in large quantities of food. They believed in small quantities, but very nutritious. Zimbabweans were complaining…. But the reality was the foodstuff was enough, you just needed to get used to it.”Footnote 67 For Green Mpofu, the culinary regime was “part of the training,” since a soldier could not go into battle with “a bulging stomach.”Footnote 68

If the Cuban army diet created the identity bafana we gapha and imbued it with pride in bodily endurance and a thin physique, the pervasive hunger also, in the words of Nico Ndlovu, “made us rascals.” This was another aspect of the identity embraced by Angolan-trained men.Footnote 69 Veterans recounted tales of sneaking out of the camp at night into the nearby villages to trade cigarettes for food or to steal from fields. Ndlovu recalled the “strained public relations” that resulted from trainees’ nighttime raids for cassava, green maize, or paw-paw. Serious though these tensions were, such stories were told with laughter and linked to “formal and informal military training.” Ndlovu recounted an incident in which his group of raiders were “attacked by villagers, with bows and arrows, just threatening us. But we were also practicing our retreat!”Footnote 70 Henry Sibasa remembered his unit using their artillery training to shell villagers’ fields so as to unearth the cassava. They snuck out of the camp at night “to go and collect,” using skirmishing tactics to make it in and out undetected. We were “naughty guys, very adventurous,” he explained.Footnote 71

These and other disciplinary breaches did not go undetected. However, the Cuban disciplinary regime was not described as unjust or disproportionate, in contrast to that at Nampundwe. The Cubans were credited with working to keep good relations with neighboring villagers, for example through food distributions, despite trainees’ raids. Punishments for acts such as leaving the camp without permission, stealing from villagers, or insubordination usually consisted of extended physical drill.Footnote 72 This was recalled as harsh but commensurate. In veterans’ accounts, Cuban discipline appeared to recognize, even embrace, the military utility of inventive rule-breaking, casting it as the work of clever rascals and not of traitors, and punishing it accordingly. The worst incidents of breakdowns of discipline—a soldier who deserted, a suicide—were attributed not to the effects of an intolerable military regime but to particular individuals’ inability to cope with the emotional stress of war and soldiering.Footnote 73 The only accounts of excessive corporal punishment involved not the Cubans but the ZIPRA camp commander Ronald Tshoka.Footnote 74

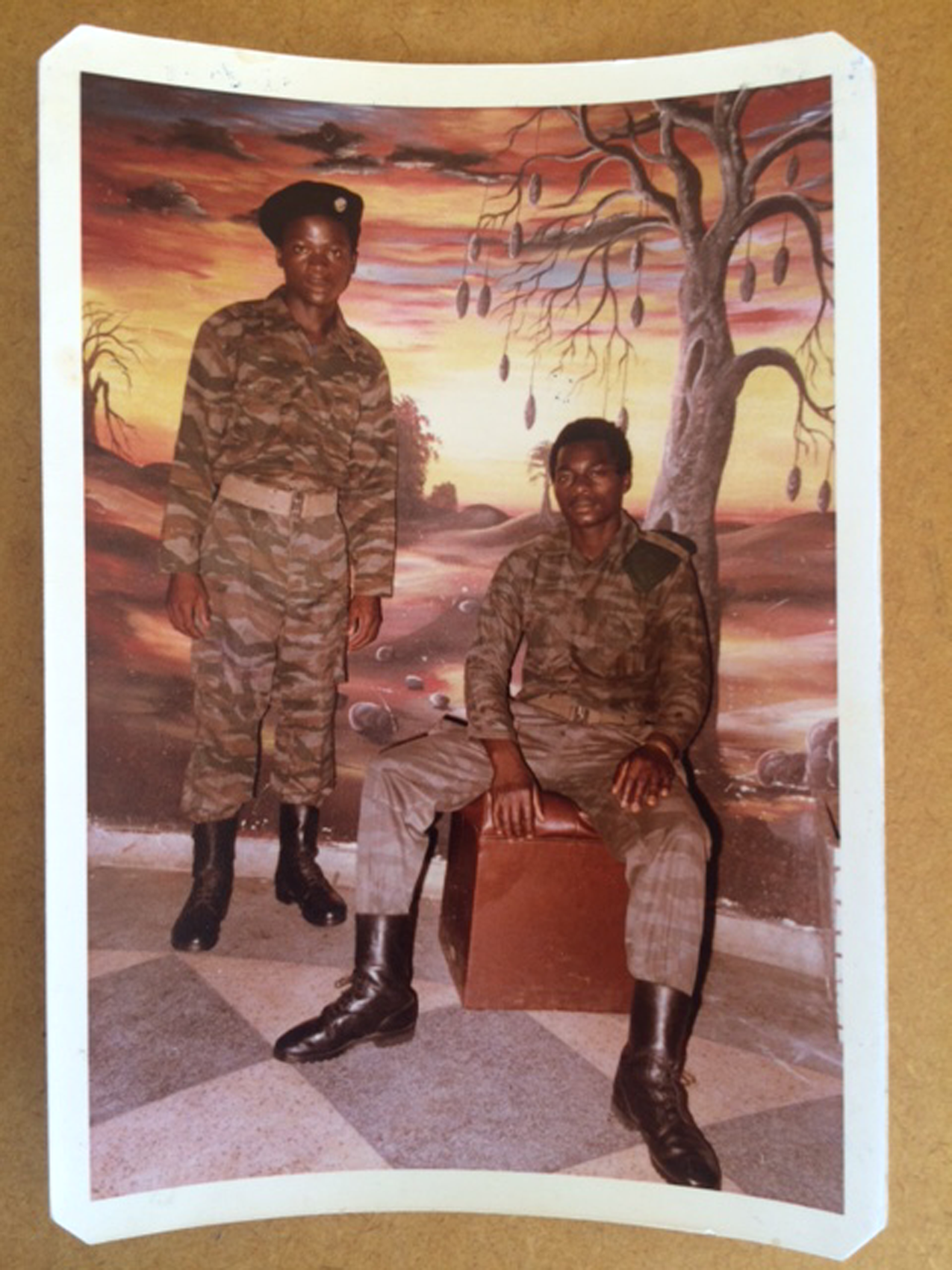

Veterans credited the Cuban regime with inculcating levels of trust that survived two major challenges: a devastating outbreak of disease in mid-1977, and the Rhodesian bombing of Boma and Luso camps in February 1979. This trust was not solely a result of the Cubans per se: in contemporaneous ANC camps in Angola, relations with Cuban instructors were at times poor, in part owing to the lack of access to the war front and the related lack of purpose attached to rigorous training, and in part, it seems, to relations with the more intrusive ANC commanders. In the ANC's case, parallel outbreaks of disease and bombing caused deep distrust and dissension and threatened the authority of the camp command.Footnote 75 Memories of Boma differed starkly from this. While loss of life from both the bombing and the outbreak was substantial, neither event produced narratives of blame or betrayal. ZIPRA veterans’ accounts instead emphasized the efforts made by the camp command to care for them and cast such efforts as evidence of internationalist solidarities and technical capacity. Stories of the disease outbreak detailed the terrible and terrifying suffering of men struck down by a mysterious sickness, but they also stressed that the Cubans and Soviets had brought international teams of medical doctors to Boma from Cuba, the USSR, Angola, and ZIPRA's Zambian camps to investigate and treat the sick: they were thus able to “save the situation.”Footnote 76 Likewise, in accounts of the devastating Rhodesian bombings, in which hundreds died and many more were severely injured, veterans told of both the lasting horror of these losses and the impressive response of the camp regime in its aftermath.Footnote 77 The attack had taken both camps by surprise, in Boma catching men gathered for arrival and departure, and little effective resistance was mounted.Footnote 78 To the extent that blame was allocated, it was to the possible enablers of the Rhodesian attack—Rhodesia's allies or informers in the camp.Footnote 79 Veterans praised the camp command, along with the Angolan military and local civilians, for the evacuation and treatment of the injured in Luena's hospitals and for airlifting others to facilities in Luanda. Image 1, taken in a Luanda photo studio, depicts two ZIPRA survivors of the Boma bombings then undergoing recuperation. Decades later, such actions were remembered as profoundly moving expressions of solidarity.Footnote 80

Image 1: ZIPRA soldiers Charles Makhuya and Snowman Moyo in Luanda, Angola, 1979. Photo used with permission from Charles Makhuya.

These accounts of Boma's material conditions, physical layout, and disciplinary regime provided the foundation for a new military imaginary. The “boys of the tin” linked their bodily endurance to the Cuban diet, and the hardships of hunger to the flourishing of a “rascal” character with military applications. Their confidence in the Cuban regime was deepened through the demonstration of internationalist solidarity and technical capacity in the face of the existential threats posed by disease and bombing. In this context, soldiers embraced the Cuban regime of military training.

TRAINING AND MILITARY IMAGINARIES: ADELANTE!

Veterans variously labeled the training offered at Boma as “conventional,” “semi-conventional,” “semi-regular,” or “advanced guerrilla warfare.”Footnote 81 They depicted the standard training as a combination of guerrilla and infantry tactics, with some companies specializing in engineering (sabotage), communications, anti-tank warfare, or mortars, alongside the more technical training in Luso camp. They described themselves as able to operate in large units (the basic unit was a company of one hundred, divided into three platoons) and use sophisticated communications systems and heavy weaponry.Footnote 82 In Shubin's account, the “syllabus” was “Soviet”: he writes that “the main task of the Soviets was to train them in the tactics of regular units,” though guerrilla tactics were also taught.Footnote 83 For the men we interviewed, the training was decidedly “Cuban,” a label filled out with a great range of meanings and feelings linked to Cuba's military history and politics.

Veterans’ shorthand for the Cuban military regime was the exhortation Adelante! This Spanish word was a battle cry, an attitude, a politics, and a strategy that together made up a distinctive military imaginary. What did Adelante! mean? Most obviously and literally, it meant going forward and expressed a particular “feeling” for war that informed all aspects of training.Footnote 84 Our interviewees used the term to mark an explicit contrast with the military imaginary of the guerrilla. Guerrillas attacked and retreated; the Cuban-trained soldier attacked and attacked again. As Green Mpofu explained, “The type of training we got was different from that in Zambia. The Cubans didn't really speak of withdrawal. They always used the words Adelante! Advance! Forwards! They never spoke of going backwards. So, it was motivating!”Footnote 85 The Cuban view, Mark Mbayiwa explained, could be summed up as, “Never give your back to the enemy. You must fight. Adelante! Adelante!” In contrast, guerrillas “were operating in small groups, firing some shots, mov[ing] away from the area.”Footnote 86 These formulations pervaded every account: Witness Bhebhe invoked the slogan “Forward ever, backward never”; Ndaba Maqeda recalled the shift from the guerrillas’ “sabotage and run” to “hit and advance,” a tactical change that enabled “advancing and putting the flags in the liberated zones.” Ben Matiwaza interpreted the lesson in terms of masculinity: the Cubans taught you to “be a man.” “They didn't want you to run. They said, no, the enemy must run.”Footnote 87

Adelante! was closely identified with veterans’ understandings of Cuban military traditions and internationalism. It built on the heroization of Cuban leaders like Fidel Castro and Che Guevara and stories of their military victories at home and abroad. Our interviewees stressed the high morale produced by Cuban instructors’ stories of combat in defense of the MPLA in Luanda in 1975–1976, or stories of older victories against Batista in Cuba.Footnote 88 These tales were seen as proof of Cuban trainers’ personal fierceness and know-how: “They have done this, they have done that, so there is nothing that can stop us from winning,” Ndaba Maqeda explained.Footnote 89 They were also taken as evidence of Cuban solidarity. Jabulani Sibanda explained that Cubans were “internationalists”—they gave up meat one day a week, he said, to support others’ struggles; men such as Che Guevara “put their lives on the line to liberate others.”Footnote 90 Green Mpofu explained, “Our cadres were very clear about the motivations of the Cubans in Angola, and they understood the principle of internationalism. So, we were quite at home with the Cubans.”Footnote 91 Race played a role in these narratives of solidarity too. Some described a sense of shared African identity with black Cuban soldiers, elaborated through stories about slavery and racial oppression in the Caribbean: “Their forefathers turned out to have been slaves [who] were taken to America…. It was very clear to us. We had the connection as Africans.”Footnote 92 The Cuban instructors were of all skin colors, however, and veterans described what were sometimes awkward exchanges with white instructors, the lessons of which were ultimately that the sacrifices of socialist internationalism trumped racial difference. “Ideology,” Ndaba Maqeda explained, “has nothing to do with the skin.”Footnote 93

The trainees also held that the Cubans had taught them to be “arrogant.” Brian Hlongwane recounted the horror the Cuban instructors felt toward one trainee, a man who had spent many years working on the South African mines, who could not give up the habit of saying “baas,” even “to somebody who's teaching [you] not to say baas.”Footnote 94 The Cubans’ use of the word jefe (chief) was universally remembered, and associated with a heroization of Castro as well as an unlimited ambition that appealed to these young men: “Whenever they spoke of Fidel Castro in Spanish they'd say ‘Jefe’, ‘Jefe de todo el mundo [chief of all the world].’ We all wanted to be like that.”Footnote 95 Charles Makhuya remembered the effects of his instructors’ exhortations: “Don't believe Smith can defeat you. You are a jefe of Smith! They boosted morale!”Footnote 96 Bonus Hlabangana recalled that the Cubans had made them feel able to defeat the Rhodesian enemy: “They said, Zimbabwe is a small country. In a day or two they'd be drinking tea with us in Salisbury.”Footnote 97

This “never reverse” set of attitudes was given credence by the Cubans’ history of fighting in Angola. It was also underpinned by confidence in the power of Soviet weaponry. Luise White has argued that the AK was the preeminent “icon of the struggle” in Zimbabwe, but in everyday usage it was given local meanings mediated by political loyalties.Footnote 98 Our interviewees echoed these insights, but they also elaborated on a wider range of weaponry, and tied it to internationalist politics. Ndaba Maqeda noted the advantages of the AK rifle over the enemy's FN, and stressed the powers of 82 millimeter mortars: “You would feel covered with it, … you would even foresee that, ah no, we will win.”Footnote 99 The “Katyusha,” a mobile multiple rocket launcher first used in World War II, was the subject of a particular mythology, though it was not used on the Zimbabwean battlefield. As Charles Makhuya recounted: “When they told us the story of defending Luanda against the South Africans, they said Fidel Castro told them that the enemy is now about 30 kilometers from capturing Luanda…. We are told by those who participated that they started to fire those Katyushas … and managed to bury the South Africans … under the sand. [They said,] So you guys will be powerful. We've got the gun, if you go to the front, we'll supply you with that gun. So, go forward, move forward, because the Katyusha is at the back!”Footnote 100 The Katyusha was cast as a symbol of the overwhelming military power made possible by international solidarity. Mark Mbayiwa recalled Joshua Nkomo promising that “Katyusha is coming,” a phrase that was echoed in and outside Zimbabwe.Footnote 101

All of these attributes were central to ZIPRA trainees’ accounts of the “high morale” inspired by the Cubans. They encouraged a belief in a training regime that demanded tremendous physical rigor, itself in keeping with an already established ZIPRA guerrilla identity, and emphasized technical know-how and live ammunition exercises. Green Mpofu recounted, “The slogan was ‘the sweat which we shed in training is the blood we'll save in battle’.”Footnote 102 Soldiers’ stories linked together drill, the acquisition of technical capacities, and learning to overcome fear. Green Mpofu, who was assigned to the anti-tank company, recalled his own difficulty in adapting to the Cuban regime: “We trained, hard as it was in terms of rations and the physical aspect. And some of the equipment we'd never seen before, such as mortars, anti-tank, communications. It wasn't that easy to familiarize ourselves. From a civilian point of view, now you're dealing with these explosives. First you have that ever-present personal fear, until you get rid of it…. Also, using guns, then using that live ammunition. Most of us we didn't have a problem after some time, gradually.”Footnote 103

The importance of live ammunition training was stressed by many of the veterans in an echo of a wider literature on the importance of live-fire training in allowing soldiers to “anticipate some of the immediate shock of combat.”Footnote 104 Ndaba Maqeda identified live-fire training as the single most important advantage of the Cuban training over that received by other ZIPRA units.Footnote 105 Bonus Hlabangana agreed: “The advantage of the Cubans was the live ammunition—so much!—compared to other camps. That helped a lot when we came back. Also the anti-tanks—so loud! It would be shaking the floor. Then when we came home, they'd be using small weapons, like playthings.”Footnote 106 Live-fire exercises, Witness Bhebhe argued, had prepared them for the demands of “real war.”Footnote 107

A pass-out parade was held for the first group of Boma graduates before they set out on the arduous return trip to Zambia. The most important dignitary in attendance was ZAPU President Joshua Nkomo, the “old man” these veterans had hoped but failed to meet in their initiation at Nampundwe. This was a very different occasion from that shocking introduction to military ways. Those standing with Nkomo included ZIPRA Commander Nikita Mangena, Deputy Chief of Operations Assaf Ndinda, and Chief of Military Intelligence Abel Mazinyane. Their presence in Boma marked the importance of the Angolan-trained men to ZAPU's fast-expanding war and shifting strategy. Mangena regaled the men with stories of military successes back home.Footnote 108 The Angolan-trained troops reciprocated by demonstrating the power of Adelante! Mazinyane recalled a “mock attack by the entire two thousand troops using live ammunition” in which “there was a lot of blowing up of things.”Footnote 109 Mark Mbayiwa vividly remembered their performance: “The Russians, the Angolan government, would provide … spotter planes bombing in the front, the soldiers are in battle formation, you're moving in an area, attacking the targets and the plane is bombing. If there's any mistake, somebody would die. You're preparing people to fight…. All these mortars, big weapons, they're firing live weapons, live ammunition.” The show was intended to “impress Nkomo. Nkomo was very excited…. He was watching, he couldn't believe it.” In Mbayiwa's view, the demonstration had convinced Nkomo of the possibilities of a new phase of war: “That's when Nkomo started talking about Turning Point,” the strategy that would bring conventional forces into play.Footnote 110

In this moment, the “boys of the tin” performed a kind of warfare they could not have imagined in their Zimbabwean homes or in Zambia's camps. It expressed a mode of fighting encapsulated in the Cuban battle cry Adelante! and enabled by the mastery of Soviet weaponry. The accounts of these men powerfully conveyed their sense of their own transformation, and their belief that it meant a new kind of war could be fought. Their formation as soldiers had many of the attributes of conventional militaries, but their military imaginaries were forged in an internationalist mold, a product of a specific instance of Cold War-era military exchange bounded by the camp. In the end, they were but one element in a highly diverse army that lacked the overarching discipline of a state. This rendered the triumphant performance of the military parade at Boma an ambiguous moment. It conveyed soldiers’ pride and sense of possibility, but it was also a vivid demonstration of a military imaginary that would prove difficult to accommodate in ZIPRA's fighting machine.

ADELANTE! IN ZAMBIA: MILITARY IMAGINARIES AT WAR

For Boma's graduates, the return to Zambia was remembered as a moment of great excitement and expectation: finally, the enemy would be engaged. Nico Ndlovu jokingly said the ideal mode of entry into Zimbabwe would have been “by parachute.”Footnote 111 Navigating ZAPU's military institutions proved a good deal more complicated than that. The first group of Angolan-trained soldiers was ready for deployment in December 1977; other groups returned in mid-1978 and early 1979, while some arrived later in 1979 following the disruption caused by the bombing of the Angolan camps or after further training elsewhere. These years were a time of rapid change in ZIPRA's institutional structures and its goals, capacities, and strategies, and also in the Rhodesian response to ZIPRA's growing threat. These changes created new possibilities but also contributed to tensions among politicians, military commanders, and soldiers.Footnote 112 We will outline the shifts in ZIPRA's war before turning to the role played in these tensions by the plural military imaginaries that typified the liberation armies of the Cold-War era.

The deployment in 1977 of large numbers of guerrillas trained in Tanzanian and Zambian camps, and the strategic decision to base them more permanently in Rhodesia under a reorganized command structure, was the necessary prelude to the introduction of larger units and heavier weaponry, and eventually the movement of conventional units into the country.Footnote 113 In 1978, these strategies drew the war into Zambia as the Rhodesian Air Force and other units infiltrated, attacked, and bombed ZIPRA's camps on an unprecedented scale in an attempt to disrupt new deployments. Zambia was considered part of the “front,” and in fact it could be more dangerous than the battle zones inside Zimbabwe.Footnote 114 Battles between Rhodesian security forces and ZIPRA conventional and other units took place on both sides of the Zambezi River, which ran along Zambia's southern border with Rhodesia.Footnote 115 The geographical focus of ZIPRA's deployments at the same time shifted decisively from the western regions of Matabeleland into the provinces north of Salisbury—notably Mashonaland West, from which ZIPRA planned to attack the capital—thus taking soldiers into camps along the eastern length of the Zambezi.Footnote 116 In these years, there were severe logistical challenges, including food shortages, owing to the vast increase in numbers of soldiers, the spread of camps and fronts, and the intensification of war.Footnote 117

The newly trained troops from Boma arrived amidst these momentous shifts, eager to fight and unconvinced of the merits of the veteran guerrilla commanders they encountered. Henry Sibasa arrived with the first contingent of Angolan-trained troops at Freedom Camp in December 1977. He laughed as he recalled, “We seemed to be rude, I think. At that time, it was caused by eagerness, eagerness to fight.” His attitude reflected the confidence acquired through training: “I'm from training, I am a trained personnel, and you want to treat me like a recruit just because you are a commander yet … the military science I know now, it's more advanced maybe than yours.” Sibasa met orders with arrogance, saying, “No, no don't waste my time, take me home,” a stance he attributed to the Cubans: “It came from those guys, they made us very confident to fight.”Footnote 118 Mark Mbayiwa agreed: “The Cubans would tell us the leader would be chosen on the battlefield. So, when we came from that particular training some people were looking down on the leadership as military people. The leadership we had before … were trained in guerrilla warfare. Then now you are coming with people trained in Angola in a bigger number, trained in guerrilla warfare and conventional warfare. Obviously, the general thinking is we know better than these people about the war.” He and others also blamed tensions with guerrilla commanders on the way that they mixed with soldiers in the camps, a practice that their Cuban training had taught them was inappropriate and which they felt compromised commanders’ authority by revealing personal weaknesses.Footnote 119

The difficulties and dangers of deployment created further tensions. Units of the first group from Boma were escorted into the country by seasoned guerrilla commanders and mixed with existing units. This was a sensitive process in which the new troops had to trust veteran commanders they did not know and whose training they did not necessarily respect.Footnote 120 The process of entering Zimbabwe was fraught with danger on both sides of the border owing to the heavy Rhodesian presence and surveillance. As Mark Mbayiwa explained, “When people were coming to cross, the Rhodesian forces could easily go to the river line, using the feasibility study to judge the likely crossing places, and in those areas, they'd lay ambushes. So, you'd come in, crossing the river, you're fired upon, two, three people die, then those who go back to Lusaka were saying the command element is selling [us out], which is not the case.”Footnote 121

In a notorious incident, a contingent of the first Angolan-trained group under the command of Assaf Ndinda, who had overseen their pass-out parade at Boma, was ambushed by Rhodesian forces on its way to the border and suffered serious losses. Some blamed ZIPRA commander Alfred Nikita Mangena, who himself was killed by a land mine while investigating the attack.Footnote 122

The dynamics behind the tensions and clashes in the Zambian camps did not exclusively affect the Angolan-trained troops, and such frustrations afflicted exiled liberation movements in many contexts.Footnote 123 Little attention has, however, been paid to the role played by the military imaginaries created by diverse training regimes, though this was one of the key prisms through which Angola-trained soldiers viewed these difficulties. As we have seen, there had always been differences among the training received by various groups and generations within ZIPRA, and all of our interviewees joked that every soldier invariably believed his training to be superior.Footnote 124 Brickhill has noted that the conventional units and their powerful weaponry inspired feelings of both jealousy and awe on the part of men trained as guerrillas.Footnote 125 Some of the distinctions among soldiers were expressed in comments about collective character traits instilled through training. The Angola-trained troops were routinely described as “arrogant” and “trigger happy” by other members of ZIPRA.Footnote 126 We have seen that they often heartily embraced this characterization and considered it fully merited by their Cuban training.Footnote 127

Yet there was more to it than this, since differences were embodied and gendered and colored by an internationalist politics. When Henry Sibasa described his cohort as “rude,” he went on to explain that their refusal of orders had taken the specific form of rejecting the “North African march” that ZIPRA commander Nikita Mangena demanded they perform. Such marches were suitable to the “sandy areas” in which their “seniors” had been trained, Sibasa held, but not to their own training lineage.Footnote 128 Such rejections underlined a collective attachment to a “Cuban” military imaginary. The distinctiveness of this imaginary was vividly elaborated in contrast to the “conventional soldier,” a category that referred specifically to ZIPRA cadres trained at Mulungushi by the Zambian army in what was viewed as a British mode. The Angolan-trained soldiers detailed differences in address, saluting, and marching, and imbued these with political meaning. Sibasa held that “those things indicated … whether you're eastern or western.” In Nico Ndlovu's words, “We thought they were British trained, so the habits were those of the British, like ‘Sir.’ We didn't want to call someone ‘Sir.’ It implies someone who is more important than the next. We considered each other ‘comrades’ because we depended on each other. Even the salute—they'd do an open-palmed salute like the British. We'd do the Russian salute.” He asked incredulously, “How can you salute with the imperialist salute?”Footnote 129 Mark Mbayiwa likewise deemed the use of “Sir” to have been “derived from a colonial point of view,” as opposed to the Cubans’ “comrade.”Footnote 130

Brian Hlongwane recounted, with a laugh, that he had rejected the open-palmed salute because it meant “putting the white [of the palm] in the front” whereas the Cuban salute “was smart on equality.” He stressed that “the Zambians, they were going the British way and we were totally different from them—the Cuban and Russian way. It set us apart.” It “meant divorce from the European system…. We are communist and we are socialists.”Footnote 131 These contrasts were extended to marching styles. The Angola-trained troops marched in the Soviet style, legs lifted high, arms crossing the body, neck locked, arrayed in a wide formation, a mode considered to be more technically demanding than the “lazy” style of British marching.Footnote 132 Brian Hlongwane recalled that the Mulungushi-trained troops “had these funny marches.… I felt they were sissies. That was my honest opinion.”Footnote 133

The Angola-trained soldiers saw their own embodied military performances as revolutionary, energetic, and manly, and different in all these ways from a “western” and “imperialist” tradition. But they also distinguished themselves from those they characterized as guerrillas. If the conventional soldier's march was “lazy,” even effeminate, the guerrillas lifted their knees too high when they marched: “even when marching, you had to be seen, you had to demonstrate that you are fit.”Footnote 134 If the term “Sir” indicated a colonialist inequality, the guerrillas were described as lacking in hierarchy. As Mark Mbayiwa explained, “The guerrillas wanted to be too independent, do things according to their own consciousness, but as the army grew up it had to change, and it changed in a painful way.” For Mbayiwa, being a soldier was “not about having a gun but understanding the gun. If you're trained to interact properly, you understand to use what weapon, when and how, not just engage in a battlefield firing weapons anywhere.”Footnote 135 Such views invoked the power of sophisticated weaponry wielded by large troop numbers, in contrast to the guerrillas’ “one man band.”Footnote 136 Brian Hlongwane explained: “The guerrillas, the older group, they were … proud of the fact that they were pioneers in that war, very proud, but we would counter and say, but we are here because you failed to get the country.”Footnote 137

These different military imaginaries created powerful tensions but also brought real, if gradual, change on the battlefield. Some veteran guerrilla commanders have described how they baulked at the growing size of the units as conventionally trained soldiers entered Rhodesia, some even refusing deployment with them.Footnote 138 Some of our interviewees recalled the inflexibility of the conventional units, who refused to be put under guerrilla commanders or to be broken up into smaller groups, despite lacking the heavy weaponry to defend large formations. They were “too disciplined,” Henry Sibasa explained, meaning they refused to adapt.Footnote 139 In the view of the bafana we gapha, perhaps unsurprisingly, it was the Angola-trained soldiers who had the biggest impact owing to their combination of flexibility, sophisticated training, and ferocious attitude. On the battlefield, they were willing to be subordinated to experienced guerrilla commanders who knew the terrain and enemy well, but they were also able to operate in bigger numbers and they brought with them a powerful arsenal, including B10s (Soviet 82 millimeter recoilless rifles) and mortars, and the technical skills to use such weapons effectively. In Brian Hlongwane's account, “the Angolans were the proudest…. Why? Because when they infiltrated the country that's when the war really heated up…. And I think that is perhaps what made them tolerated by the guerrillas, because those could work together.”Footnote 140 Henry Sibasa, who became a commander in ZIPRA's Southern Front, explained that the Angola-trained soldiers and guerrillas were “operating as one.” The guerrillas were “very experienced and … they had great advice for us.” Sibasa's group introduced the Cuban “hit and attack” tactics over time: “At first they could not understand that, but as time went on gradually they joined us, they really understood us.”Footnote 141 Witness Bhebhe put it simply: the Angolans became the “backbone” of ZIPRA.Footnote 142

CONCLUSION

The Cuban training of ZAPU's soldiers in Angola enabled a strategic shift in ZIPRA's war and created a distinctive military imaginary that has endured for some forty years. Veterans of the Angolan camps vividly recalled how Cuban instructors had transformed their ideas of what it meant to be a “proper” soldier and what kind of war they should fight, inculcating a vision of revolutionary semi-conventional warfare and a linked set of embodied practices and feelings bolstered by their readings of Cuban politics and history. But this imaginary was just one among others developed among ZIPRA soldiers trained under the banner of a militarized internationalism. The military imaginaries of liberation movement armies were not driven by a single, dominating state; ZIPRA soldiers could not be imagined as “the state.” They were rather produced by disparate camp regimes scattered across the globe, granting liberation armies both innovative and unstable qualities.

The stories of ZIPRA's Angolan-trained soldiers draw attention to a neglected aspect of Cold War-era exchange— military training. By so doing, they cast light on what made liberation armies unusual in comparison to both conventional militaries and the rebel movements of the post-Cold War era. Our account shows just how significant these exchanges were in shaping the experiences, technical capacities, and dispositions of thousands of soldiers. Angolan-trained ZIPRA cadres’ ideas of soldiery shaped the advances and tensions of the war effort and created a prism for remembering these military experiences. They saw themselves as distinct from two other categories of ZIPRA soldier: the “imperialist” conventional troops produced by Zambian training, and the “hit and run” guerrillas produced over decades in a great number of far-flung camps. Paying attention to the plural military imaginaries of liberation armies allows for a new appreciation of them, and of this historical moment.

The focus on camps as places of military training also offers a new view on liberation movements’ transnational lives. The rich studies of camps have rarely scrutinized military training per se. Examining this aspect of camp regimes allows us to develop new understandings of soldiers’ experiences and memories, alongside the military trajectories of liberation armies. Our account shows the camp to be the preeminent venue for “militarization,” but in highly uneven and shifting ways built up over the life of the struggle. From their own experiences of division and violence in the Tanzanian camps, Nampundwe's instructors forged an initiation process for the young arrivals in Zambia that was experienced as a brutal shock and remembered with deep ambivalence. In our interviewees’ stories, this first encounter with military life served as a counterpoint to the elaboration of Adelante! as military imaginary in Angola. When the “boys of the tin” returned to the Zambian camps, they did so with a sense of superiority over their one-time guerrilla commanders. These dynamics created new capacities and tensions that powerfully shaped the wars liberation movements fought.

ZIPRA veterans’ accounts of their formation as soldiers by Cuban instructors in Angola offer testimony to an extraordinary era of internationalist military exchange. The Cuban exhortation Adelante! encapsulated a powerful military imaginary and stands as testimony to the enduring effects of military training itself, to the legacies of Cold War-era international solidarity in soldiers’ memory, and to the essential contribution veterans’ oral histories can make to global military history.