Introduction

In early models of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) it was hypothesized that negative thoughts were underpinned by stable cognitive structures called schemas, which represented an individual's past learning experiences (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979). It was suggested that schemas could be dormant for long periods of time, but become activated by particular triggering events, such as real or perceived loss. Once triggered, the underlying schemas would escalate and generalize, leading to the full psychiatric disorder. It was proposed that, via the notion of schemas, we would be able to produce better conceptualizations, which in turn would allow us to gain a better theoretical understanding of patients' problems, and thereby help target interventions more appropriately.

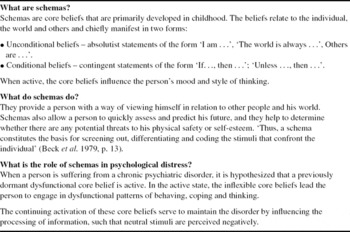

Despite the credibility that CBT therapists have assigned to this concept (Kovacs & Beck, Reference Kovacs and Beck1978; Platts et al. Reference Platts, Tyson and Mason2002), there is a lack of agreement regarding its definition. For example, schemas are sometimes viewed as unconditional beliefs (‘I am incompetent’), conditional beliefs (‘If I make a mistake, people will lose respect for me’) or rules of behaviour (‘I must always do something perfectly’) – James et al. (Reference James, Southam and Blackburn2004). James et al. (Reference James, Southam and Blackburn2004) provide a critical review of the difficulties associated with the definition, and note that many of the terms are incorrectly used interchangeably: interpersonal schemas (Safran, Reference Safran1990); person and self schemas (Horowitz, Reference Horowitz1991); early maladaptive schemas (Young, Reference Young1994); core beliefs (Beck et al. Reference Beck and Freeman1990). Further, distinctions have been made at the structural and process (i.e. biases) levels by Hollon & Kriss (Reference Hollon and Kriss1984) (see also Williams et al. Reference Williams, Watts, MacLeod and Mathews1997).

Hence, while the concept of the schema was originally introduced in order to help improve our conceptual understanding of people's distress, in practice its use may lead to greater misunderstanding.

The present study examines CBT clinicians' definitions of schemas in terms of the content communicated to other professionals. Such information is useful because it helps us determine the manner in which the notion is both explained, and employed, in therapy, training and supervision. The study investigates the views of a wide range of clinicians at various stages of their training. Such a disparate set of participants was approached because we were interested in how the concept was being communicated within the broad church of the CBT community. It is hypothesized that the most comprehensive definitions will be provided by the participants with a recognized qualification in CBT. However, we were also interested in the views of a group of psychology trainees, owing to the fact that their initial exposure to the notion of schemas was as psychology undergraduates. In this context, they will have been introduced to the cognitive psychology (CP) perspective of schemas as features of memory and learning (Bartlett, Reference Bartlett1932). In CP, it is suggested that actions, thoughts and sensory experiences become grouped together in stored scripts waiting to be activated under the appropriate setting conditions (e.g. the schema for driving a car becomes activated once one sits behind the steering wheel of a car; see James et al. Reference James, Southam and Blackburn2004). We expected that previous exposure to this broader perspective would lead to elaborated definitions from the trainee psychologists.

Postgraduate trainees in CBT, typically in the final phases of their training, were also recruited for the study. This group was included because the trainees were undertaking an intensive period of learning with respect to CBT theory and practice. They were having to: attend weekly lectures from recognized experts from around the UK; attend weekly case supervision; write case studies and assignments. Hence, they were being routinely tutored in ‘state of the art’ CBT material – including many disorder-specific models with the diathesis-stress framework at their centre.

Method

Participants

Seventy-two participants submitted definitions. All attended a CBT teaching session which included a section on schemas. The sessions were run by the first author (I.J.) in Britain and Ireland between 2005 and 2007. The participants varied: nurses (33.3%), qualified clinical psychologist (26.4%), trainee clinical psychologists (29.2%), psychiatrists (6.9%), social workers (2.8%), and teachers (1.4%). Nineteen (26.4%) of the sample had a formal CBT qualification, either a diploma or certificate. All of the other participants, except the trainee clinical psychologists, were attending the sessions as part of their postgraduate training in CBT. The majority (78%) of the postgraduate group were in the final 2 months of a 9-month training course. The trainee psychologists were in the second year of their training on a doctorate course whose main therapeutic model was CBT.

Procedure

Prior to teaching the section on schemas, I.J. gave the participants the following instruction: ‘If a CBT trainee asked you to define a schema, what would you say?’

This particular question was asked because the answers would provide a sense of how the concept was being communicated and ‘passed-on’ amongst generations of therapists (and perhaps indicate how the concept is communicated to patients).

The resulting definitions were collected and their content analysed independently by an assistant psychologist (H.T.), who had no prior training in therapy. She initially examined the written data for emerging themes. The themes were then re-examined to identify commonalities. After an iterative process of re-examination and re-grouping, H.T. was left with 14 core themes. These themes were thus viewed as the key features underpinning CBT therapists' definitions of schemas.

H.T. developed a marking grid that outlined the nature of each theme and additionally provided a practical example of the themes.

The marking grid was discussed with the other authors (I.J., K.R.) of the present study to check for overlap and ensure the examples had some therapeutic relevance – given H.T.'s clinical inexperience. Following clarification of two definitions, she took 20 of the participants' definitions and used the marking grid to score the responses against the themes (Table 1). One mark was given for each theme that appeared in the definition. H.T.'s results were examined against a second marker (K.R.) to establish inter-rater reliability. Reliability for the blind rating was found to be good (Kappa across 14 themes: 0.845 with agreement between 70% and 100%). H.T. then analysed all 72 definitions, which included re-analysing the original 20 from the reliability stage.

Table 1. Thematic grid: themes of schemas, with examples and relevant percentages

As a way of assessing the construct validity of the marking grid, it was tested against an ‘ideal’ definition produced by a group of four CBT experts. All of the experts had strong links to the Newcastle Postgraduate Diploma Course in Cognitive Therapy, University of Durham. They were national experts in CBT and involved in the training and supervision of trainees on this course. All had published articles on CBT in highly regarded national and international journals. They produced the definition as part of a related project on schemas conducted by the present group of authors (A. Howarth, I. James, M. Freeston, unpublished observations). Their instruction for constructing the definition was to produce a comprehensive definition of a schema from a Beckian perspective. The definition is outlined in Table 2.

Table 2. Experts' definition

The results of the validity check are outlined in the ‘Results’ sections.

Results

The 14 themes identified are described in Table 1, together with examples from the marking grid. Almost 70% (n = 50) of the participants used the term ‘belief’ within their definitions, and over 60% (n = 44) stated the relevance of an information-processing perspective (Table 1). The remaining themes were indicated far less frequently.

In relation to the marking grid, the highest score achieved by any participant was 6 out of 14 themes (five participants, 6.9%). The modal score was 2 (23 participants, 31.9%). Ten people (13.9%) scored only 1 on the grid, the majority of these simply stating that ‘schemas are core beliefs’. The mean for the group was 2.86 (s.d. = 1.38); there were no significant differences observed with respect to the comparisons between professional groups. The small number of participants did not allow for further analysis regarding professional background, training status and level of CBT qualification. However, high scores were not evident in those groups that one may have expected to perform well (Table 3).

Table 3. Means and standard deviations (S.D.) of scores on thematic grid by profession and qualification

Validity check using ideal definitions of schemas in Table 2

The ‘ideal’ definition scored 10 out of 14 on the marking grid, suggesting that the grid covered many of the key areas outlined in a comprehensive definition. The ideal definition failed to score on ‘How schemas were formed’; ‘Relevance to CBT’; ‘Notion of functionality’; ‘Running outside of conscious awareness’.

Two of the four CBT experts were asked to assess whether there were any features present in the ‘ideal’ definition not covered in the grid. Only one additional item was suggested, the notion that when schemas are active, ‘neutral stimuli’ can be perceived negatively.

Discussion

Therapists and trainees from different professions, some with postgraduate CBT qualifications, provided definitions of a schema. From the clinicians' definitions, it emerged that the concept is made up of a wide range of themes. Indeed, in the present analysis, 14 themes could be identified and reliably described by an independent rater. The two main themes identified consistently by many of the participants were ‘beliefs’ and ‘information processing’, which reflected the main elements of the experts' definition.

The diversity with respect to the participants permitted an exploration of whether demographic variables such as professional background influenced the comprehensiveness of the definitions. However, there were few differences in levels of complexity of the descriptions across professions. In truth, individual definitions tended not to be comprehensive, with a mean of less than three themes per definition. Only 6.9% participants included more than five themes (i.e. five participants scored 6 on the marking grid). Ten of the definitions contained only one theme. The most frequently endorsed themes were ‘beliefs’ and ‘information processing’. However, it is relevant to note that these themes were absent from a considerable number of definitions.

From the present study it is evident that clinicians think schemas are composed of a number of different features. However, they tend to be rather succinct in the manner in which they describe schemas. We consider such brevity to be a potential problem, and argue that the use of more comprehensive definitions would aid communication and understanding between clinicians, patients, supervisors and trainers regarding the concept. For example, within a supervisory relationship, without a detailed and shared understanding, two people may appear to agree on a treatment strategy, but unknowingly work at the schema level very differently. Hence, consider a situation where a trainee therapist believes that schemas are only formed in childhood. In contrast, his/her supervisor holds the view that schemas are formed across the lifespan (James, Reference James2003). Thus, when the supervisor asks the trainee to undertake some schema work with an 80-year-old client, she is initially surprised by, in her view, the ‘excessive’ focus on the patient's childhood. Such a matter can obviously be dealt with in the next supervision session, but the event illustrates how a lack of a shared understanding can interfere with the therapeutic process.

Owing to such occurrences, it is thus suggested that working with different conceptual understandings may result in inefficient therapeutic and supervisory input, and at the worst it could lead to harmful practices (James, Reference James2001).

The present study should be viewed as a piece of exploratory research, requiring further programmatic investigation. Indeed, it does not claim to have captured a representative view of schemas in the therapeutic community. The study may be criticized in a number of areas; for example, one can argue that there were too few therapists participating who had a formal qualification in CBT (26.4%). Hence, it may be said that the results are not an accurate reflection of CBT therapists' abilities at defining the concept. In response to this criticism, it is relevant to note that a key feature of this work was to determine how the concept was being ‘passed on’ within the CBT community. Indeed, not all therapists professing to be CBT in their orientation possess a formal qualification in CBT. Further, it is important to remember that the groups who were ‘in-training' were receiving intensive CBT teaching from highly qualified therapists, and thus their ideas were in part a reflection of their mentors’ perceptions. Pre-qualified clinical psychologists were selected because we were interested in determining whether the earlier CP experience of the trainee psychologists served to expand their definitions; which turned out not to be so.

While we believe that overall our findings are worthy of note, we acknowledge that they are based on a grid derived by a person who did not have previous experience in CBT or therapy (i.e. Table 1 – thematic grid). This aspect has its pros and cons. For example, the assistant did not have any prior expectations or biases. However, we also recognize that the resultant ‘themes and definitions’ need to be treated with some caution. Hence, we acknowledge that the grid itself is in need of adaptation and development in order to be an acceptable and utilizable taxonomy.

One must also be cautious about over-interpreting the findings, owing to the wording of the question posed to the participants. Indeed, we may have received more comprehensive definitions if we had emphasized the need for a detailed response, or one that conveyed the participants' level of understanding.

A further potential criticism concerns the suitability of the experts' definition as an examplar description. Such a criticism is valid, but it is important to note that the experts were some of the top trainers and presenters in the UK. As such, their views are important and influential. Any lack of agreement also illustrates that, as yet, there is no general agreement in the literature about the nature of schemas: Are they the same as core beliefs, underlying assumptions, information biases? If not, in what ways do these aspects differ from each other (James et al. Reference James, Southam and Blackburn2004)? Related to this lack of clarity, it could be argued that those readers who find themselves disagreeing with the definition are in many ways confirming the argument underpinning the present study, i.e. the nature of schemas is poorly understood and defined, because even the experts are unable to agree!

Conclusion

This study has examined clinicians' definitions of schemas, and has produced a marking grid for assessing the degree of comprehensiveness of the descriptions. The grid is clearly in need of further development, but has the value of being derived from first principles by someone naive to training in therapy. The work has demonstrated that clinicians generally agree that schemas are related both to ‘beliefs’ and the ‘information-processing system’; such views were also expressed with the experts' definition. However, on the whole, the participants' used rather short succinct definitions with respect to this important concept. We believe that such brevity is a problem because it may limit the level of debate, and veil key issues worthy of clarification. In clinical practice, at its worst, an insufficient understanding of schemas may lead to ineffectual and sometimes even harmful interventions. We acknowledge the shortcomings of this piece of work, but think it has highlighted a potential problem in how we communicate our understanding of a key concept in CBT.

Main points

The concept of schemas is used widely by cognitive behavioural therapists in many aspects of their clinical and theoretical work. The present paper suggests:

(1) The concept is poorly defined with numerous terms being used synonymously (e.g. core belief, rules, assumptions, etc.)

(2) Clinicians may inadvertently assume a shared conceptual understanding of the concept and this may lead to problems and inconsistencies when engaging in therapeutic work.

(3) Clinicians, particularly when in a supervisory or training role, should make a point of discussing their understanding of schemas. Further, they should promote debate about how different conceptual views can influence clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

This project was approved as a service evaluation project by the Research and Development Department of the NTW NHS Trust.

Declaration of Interest

None.

Learning objectives

• To encourage clinicians to acknowledge the importance of operating with clear conceptual definitions of key therapeutic concepts.

• To help clinicians develop a better understanding of the notion of schemas.

• To encourage supervisors and trainees to define their conceptual views relating to schemas, and promote discussion of these views amongst trainees.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.