Judicial power is often limited by courts' reliance on other actors to implement their rulings (Carrubba and Gabel Reference Carrubba and Gabel2015; Carrubba, Gabel and Hankla Reference Carrubba, Gabel and Hankla2008; Hall Reference Hall2014; Johns Reference Johns2015; Kapiszewski and Taylor Reference Kapiszewski and Taylor2013; Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg2008; Vanberg Reference Vanberg2001; Vanberg Reference Vanberg2005). To promote compliance, courts therefore employ strategies designed to legitimize their judgments (Hume Reference Hume2006; Larsson et al. Reference Larsson2017; Lupu and Voeten Reference Lupu and Voeten2012), raise public awareness (Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel2016; Staton Reference Staton2006) and enable pro-compliance constituencies to monitor implementation (Gauri, Staton and Cullell Reference Gauri, Staton and Vargas Cullell2015; Staton and Romero forthcoming). However, few scholars have evaluated whether such strategies are effective (Keck and Strother Reference Keck and Strother2016, 3; but see Gauri, Staton and Cullell Reference Gauri, Staton and Vargas Cullell2015; Staton and Romero Reference Staton and Romero2019). Thus we know that courts act strategically to promote compliance, but we do not yet know the conditions under which such strategies may succeed.

I investigate judges' ability to promote compliance in the context of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). Despite being considered ‘the most effective human rights regime in the world’ (Stone Sweet and Keller Reference Stone Sweet, Keller, Helen and Stone Sweet2008), the ECtHR faces significant compliance problems (Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2014a; Hillebrecht Reference Hillebrecht2014b). While the ECtHR traditionally leaves the identification of remedies to respondent states, its compliance problems have motivated the Court to start spelling out necessary remedies in selected judgments (Keller and Marti Reference Keller and Marti2015, 836).Footnote 1 Such remedial indications may enable pro-compliance actors to argue more forcefully that specific remedies are necessary and to credibly call out non-compliance (Spriggs Reference Spriggs1996, 1127; Staton and Vanberg Reference Staton and Vanberg2008).

To investigate the efficacy of the ECtHR's new remedial approach, I employ an original dataset of ECtHR judgments and their implementation by respondent states. The dataset includes information concerning both (1) required remedies and other judgment characteristics and (2) the length and outcome of the compliance process.Footnote 2 Using these data, I consider how remedial indications affect compliance by respondent states.

After conditioning on the factors that influence the ECtHR's decision to indicate remedies, I find that judgments containing remedial indications are implemented faster than comparable judgments without such indications. Remedial indications are particularly helpful when the institutional context enables pro-compliance actors to hold governments accountable. These findings suggest that courts can succeed in promoting quicker compliance with their judgments. Importantly, spelling out necessary remedies is a strategy that is available to a variety of courts and other actors that delegate implementation tasks.

Remedial design and the politics of compliance

By flouting compliance, public authorities can undermine the impact of judicial decisions rendered against them. In political systems where outright defiance is relatively rare, the actors responsible for implementation can often ‘resist and delay’ compliance with judgments they dislike (Kapiszewski and Taylor Reference Kapiszewski and Taylor2013; Staton Reference Staton2004, 42, see also Gauri, Staton and Cullell Reference Gauri, Staton and Vargas Cullell2015). Although political changes or mounting public pressure may eventually lead to compliance, the resulting delays prolong the denial of justice for affected individuals and can undermine the importance of courts as vehicles for social change (Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg2008).

Vagueness concerning what a judgment requires may contribute to the lack of timely compliance (Kapiszewski and Taylor Reference Kapiszewski and Taylor2013, 815; Staton and Romero forthcoming; Staton and Vanberg Reference Staton and Vanberg2008). For instance, the Supreme Court of the United States held in its 1955 Brown v. Board of Education II ruling that school districts were to be desegregated ‘with all deliberate speed’. Scholars have argued that the lack of more specific directions contributed to prolonged defiance of the ruling by recalcitrant local authorities (for example Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg2008).

By indicating remedies, courts can make it easier to hold responsible authorities accountable for delays or outright defiance (Staton and Romero forthcoming; Staton and Vanberg Reference Staton and Vanberg2008). Diffuse support for the judiciary (Gibson, Caldeira and Baird Reference Gibson, Caldeira and Baird1998) or public support for specific decisions (Hall Reference Hall2011) often make it costly for political actors to openly defy judgments. Such costs presupposes, however, not only that the relevant audiences are able to punish defiance, but also that they can detect recalcitrant behavior (Vanberg Reference Vanberg2005). Compliance monitoring by the media and civil society is therefore considered important for timely compliance (Cavallaro and Brewer Reference Cavallaro and Brewer2008; Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel2019). By clarifying what compliance should entail, remedial indications facilitate such compliance monitoring and enable NGOs and other compliance constituencies to credibly call out attempts to evade the ruling.

Remedial indications can also provide ‘political cover’ (Allee and Huth Reference Allee and Huth2006) for actors required to implement unpopular remedies and may help prevent disagreement within a responding government concerning how to implement the judgment (Baum Reference Baum1976, 94; Spriggs Reference Spriggs1996, 1124). These different mechanisms may operate either in combination or individually in different cases. In any event, remedial indications can be expected to promote timely compliance:

Hypothesis 1

Judgments containing remedial indications are complied with more quickly than comparable judgments without remedial indications

The effectiveness of remedial indications is likely to depend on the costs of ignoring them. As argued by Staton (Reference Staton2010, 198), the costs of openly defying judicial decisions will be greater when a critical media, an active civil society, independent national courts and free elections enable the public to hold governments accountable. If such institutions are relatively weak, it becomes less likely that remedial indications are used to effectively hold public authorities accountable:

Hypothesis 2

The relationship between remedial indications and quicker compliance is stronger where domestic institutions enable holding governments accountable.

There are also disadvantages associated with remedial indications. Perhaps most importantly, responding authorities are often better situated than judges to identify appropriate remedies (Staton and Romero Reference Staton and Romero2019; Staton and Vanberg Reference Staton and Vanberg2008). If responding authorities act in good faith, it may therefore be beneficial to grant them some leeway over how judgments are implemented. Moreover, if remedial indications are unsuccessful at facilitating prompt compliance, the increased visibility of the compliance problem may cause additional damage to the Court's reputation and desensitize important audiences to non-compliance (Staton and Vanberg Reference Staton and Vanberg2008).

The provision of remedial indications may therefore – if judges are acting strategically – be limited to cases in which compliance is difficult to achieve and it is likely that they will be helpful. When testing the above hypotheses, it is therefore crucial to account for factors that influence judges' remedial approaches. The remainder of this letter develops and employs such a research design to investigate whether the ECtHR has been able to promote timely compliance by selectively indicating remedies.

Research design

The ECtHR provides a particularly useful context for assessing how remedial indications influence compliance with judicial decisions for two reasons. First, in contrast to most courts, reliable data are available concerning compliance with ECtHR judgments. Secondly, the transition to the new remedial approach has been relatively cautious and judges have disagreed about their legal competence to indicate remedies (see, for example, the dissenting opinions in the 2017 Moreira Ferreira (No. 2) v. Portugal judgment). Thus scholars and judges have noted that there is a ‘haphazard’ aspect to when remedial indications are provided (Donald and Speck Reference Donald and Speck2019, 114). Such inconsistencies facilitate comparisons between ECtHR judgments that contain remedial indications and similar judgments that do not.

Compliance with ECtHR Judgments

I employ an original dataset containing compliance data for all ECtHR judgments rendered by 1 June 2016. Compliance is measured based on information from the Committee of Ministers (CoM), which supervises implementation of ECtHR judgments. The CoM supervision is conducted by a strong and professionalized secretariat, which contributes to its reliability (Çali and Koch Reference Çali and Koch2014; also see the Appendix). Supervision is organized by lead cases, which are judgments revealing new issues in a respondent state. Later judgments relating to the same issue within a particular state are monitored in conjunction with the lead case. Lead cases are therefore the appropriate units of analysis (Grewal and Voeten Reference Grewal and Voeten2015; Voeten Reference Voeten2014).

When no further measures are needed, the CoM closes its supervision through a final resolution. Final resolutions thus provide a measure of compliance understood as the ‘full execution of the action (or complete avoidance of the action) called for (or prohibited)’ (Kapiszewski and Taylor Reference Kapiszewski and Taylor2013, 806). The duration of the compliance process is measured as the number of days between the lead case judgment and the final resolution. A censoring indicator captures whether compliance was achieved by 1 June 2016, the last date of observation.

Remedial Indications

I identified 202 judgments with remedial indications rendered before 1 June 2016.Footnote 3 These judgments concerned 143 different lead cases. In 102 cases, remedial indications were offered in the lead case judgment. In the remaining cases, indications were only given when the ECtHR was presented with a repetitive case. I create a time-varying dummy which takes a value of 0 until the ECtHR has indicated remedies and 1 thereafter.

Government Accountability

Hypothesis 2 anticipates that the effect of remedial indications is conditional on the ability of pro-compliance actors to hold governments accountable. To measure this ability, I use the Varieties of Democracy project's ‘accountability index’. This index measures the ‘ability of a state's population to hold its government accountable through elections’, through ‘checks and balances between institutions’, and through ‘oversight by civil society organizations and media activity’ (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2018). These different subtypes of accountability institutions are likely to work in conjunction to hold governments accountable for their compliance performance. My preferred approach to testing Hypothesis 2 is therefore to use this combined accountability index. In the Appendix, I consider additional models using each of the main subcomponents of the index.Footnote 4

Conditioning on Case and Country Characteristics

To compare similar judgments with and without remedial indications, I condition on case and country characteristics that may influence both the provision of remedial indications and subsequent compliance. Relevant case characteristics include the types of remedies needed for compliance, the complexity and character of the identified human rights violation(s), and when the judgment was rendered. Country-level confounders include the bureaucratic capacity of the respondent state, domestic veto players, the degree of democratic consolidation, the proximity to an election and the extent to which domestic institutions help to hold governments accountable. These variables are discussed further in the Appendix.

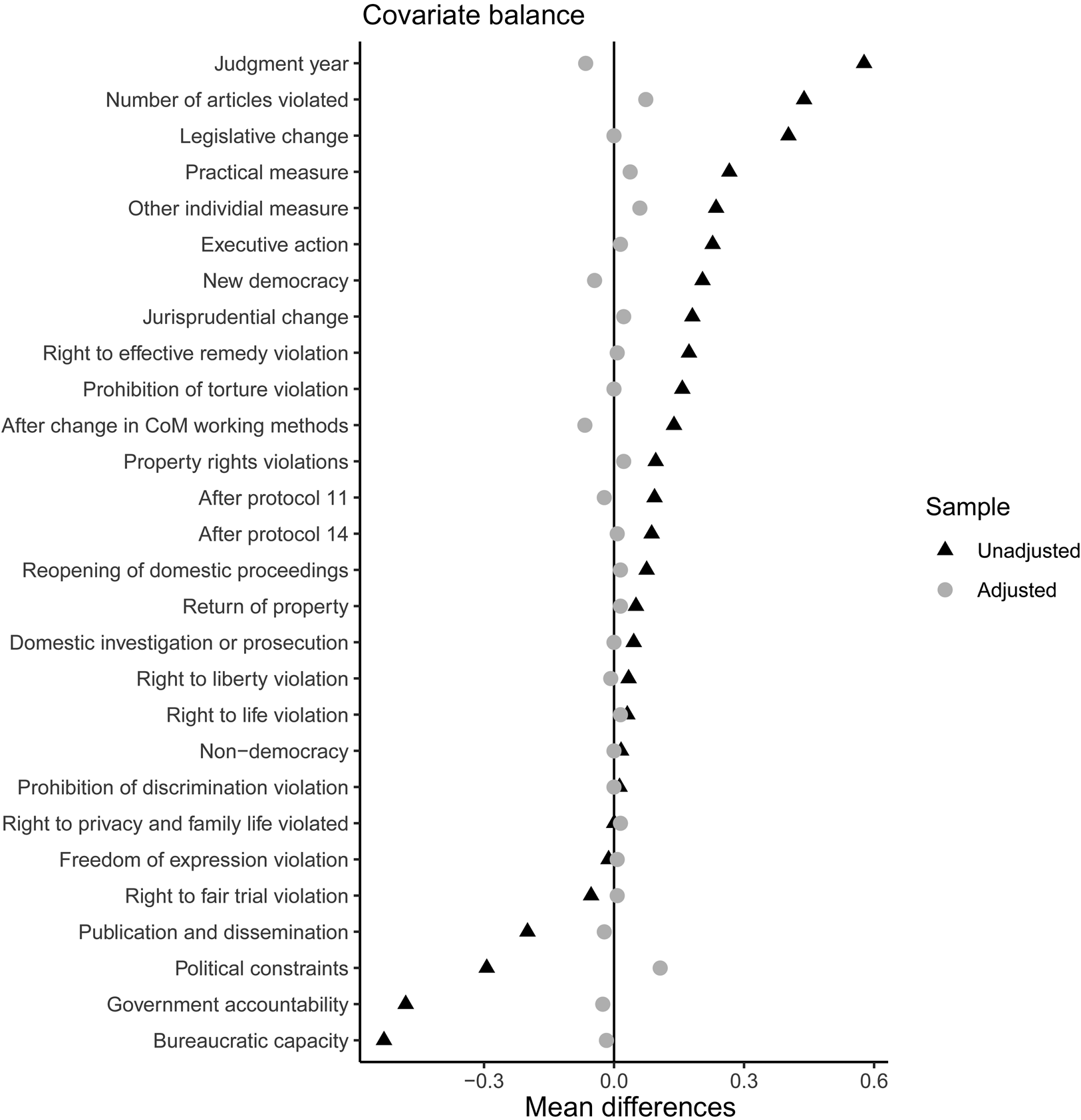

I first pre-process the data using genetic matching (Diamond and Sekhon Reference Diamond and Sekhon2013; Sekhon Reference Sekhon2011). Matching adjusts for the differences between judgments with and without remedial indications by identifying ‘control cases’ that are as similar as possible to the ‘treatment cases’ on confounding variables. This procedure also reduces model dependence by avoiding extreme counterfactuals concerning cases that are very different (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Imai, King and Stuart2007). The matched dataset contains a total of 252 unique cases. Of these, 134 cases contain remedial indications,Footnote 5 while 118 do not. Although these cases represent a small percentage of the overall ECtHR caseload, they are the most informative cases concerning the effectiveness of the Court's remedial indications.

The matching procedure and the resulting improvement in covariate balance is illustrated in Figure 1, which displays differences in means on the included covariates before and after matching. If treated and untreated cases are comparable, differences should be close to 0. The figure shows that remedial indications tend to be offered in cases involving multiple violations that require challenging remedies from states with relatively weak bureaucratic capacity and accountability institutions. After matching, these differences are greatly reduced.

Figure 1. Covariate balance before and after matching

The matching procedure does not produce perfect balance; multivariate modelling is therefore needed to further adjust for confounding variables (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Imai, King and Stuart2007, 201). The multivariate models also account for developments in variables that change during the course of the implementation process, such as election proximity.

Conditioning can only adjust for observable differences between judgments. This strategy does, however, result in balance on the variables that influence both the ECtHR's decision to indicate remedies and subsequent compliance. Because the ECtHR's shift in remedial approach has been inconsistent and comparisons are made between very similar cases, it is credible that differences in time until compliance are attributable to the remedial indications.

Estimation

I use the Cox model,Footnote 6 which avoids making assumptions concerning how the likelihood of compliance varies depending on the time since the judgment and allows for time-varying covariates (Box-Steffensmeier and Jones Reference Box-Steffensmeier and Jones2004). Formally, I estimate variations of the following model:

where t is the number of days since the judgment, h i(t) is the probability that judgment i will be complied with at time t conditional on the judgment remaining unimplemented at that time, and h 0(t) is the (unspecified) baseline hazard of compliance. Indicationsi(t) is a dummy variable that takes a value of 1 if the ECtHR has provided remedial indications for judgment i at time t and 0 otherwise. Controlsi(t) is the vector of control variables, some of which are time varying.

The model estimated to evaluate Hypothesis 2 also includes a multiplicative interaction between Indicationsi(t) and the respondent state's level of government accountability. Because the same states are subject to multiple judgments, I cluster the standard errors at the state level.

Results

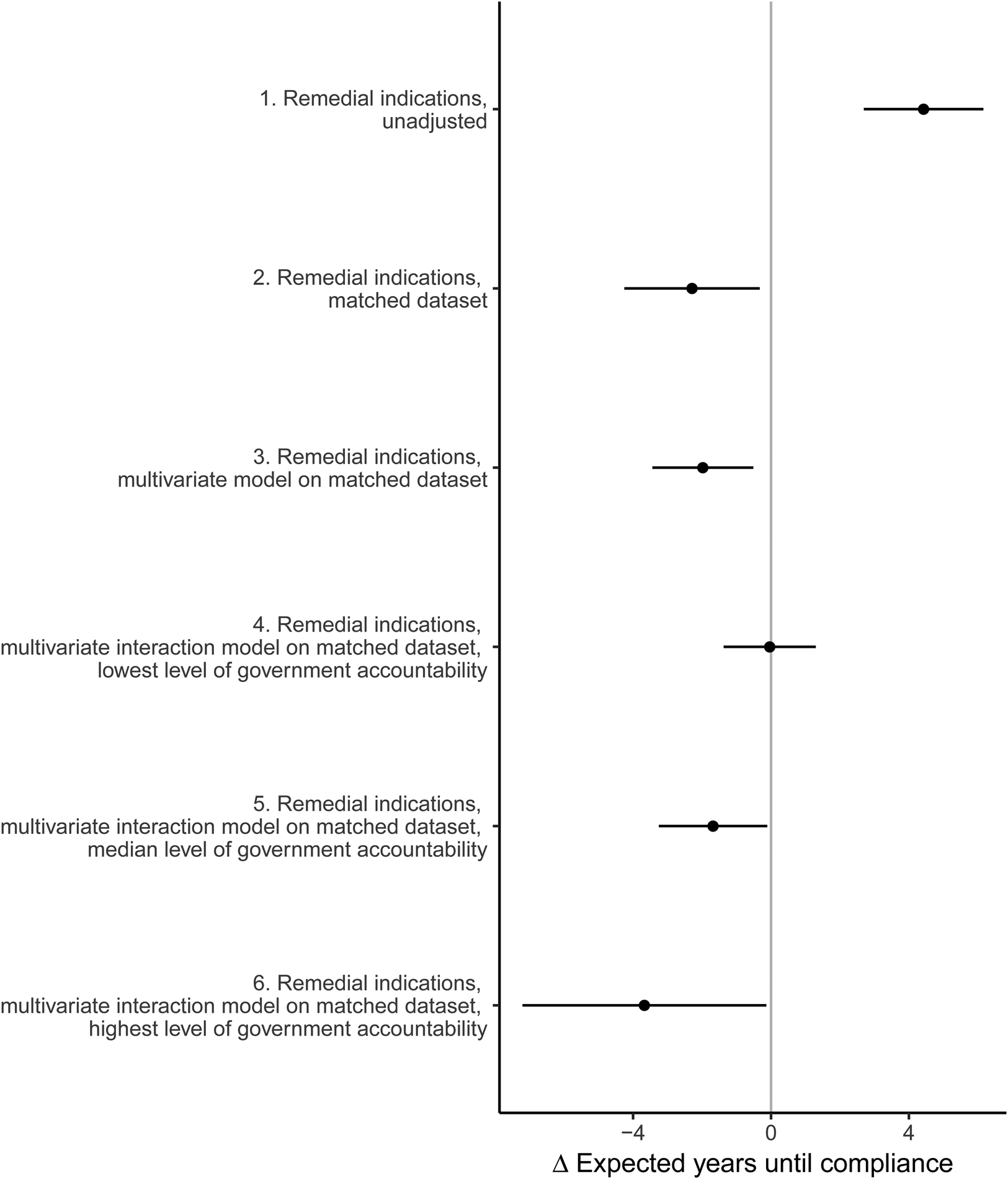

Figure 2 displays average marginal differences in time until compliance associated with remedial indications, calculated using the method proposed by Kropko and Harden (Reference Kropko and Harden2017). The error bars indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals. The full Cox models are reported in the Appendix.

Figure 2. Marginal differences in years until compliance associated with remedial indications

Note: error bars indicate 95 per cent confidence intervals.

To show how conditioning on case and country characteristics influences the results, the first marginal difference is based on a model estimated on the full dataset before conditioning on control variables. This model suggests that judgments containing remedial indications are, on average, implemented 4.4 years later than other judgments. This difference is considerable, as the median time until compliance is less than 3 years. This bivariate relationship is explained by remedial indications being offered in challenging judgments. The remaining marginal differences are based on models that condition on potential confounders.

The second marginal difference is based on a bivariate model estimated on the matched dataset. This model suggests that judgments containing remedial indications are, on average, complied with 2.3 years before comparable judgments without such indications. The relationship between remedial indications and quicker compliance also holds in the multivariate model, which accounts for remaining differences between the cases containing remedial indications and those that do not. Based on this model, the third marginal difference suggests an approximately 2-year average reduction in time until compliance if remedial indications were provided. In line with Hypothesis 1, there is thus evidence that remedial indications are associated with quicker compliance.

In the Appendix, I show that this finding also holds in other model specifications, including a model based only on within-state variation and a multivariate model estimated on the full data (without matching).

Hypothesis 2 anticipates that the effect of remedial indications is conditional on the strength of accountability institutions. To investigate this hypothesis, the remaining marginal differences are calculated based on a model that interacts remedial indications with the level of government accountability.

The fourth marginal difference is the conditional effect of remedial indications when government accountability is at the lowest level observed in the matched dataset (Azerbaijan in 2016). The difference in time until compliance is approximately 0, suggesting that remedial indications do not promote quicker compliance if pro-compliance constituencies have very few means of holding governments accountable for non-compliance.

At the median level of government accountability (Turkey in 2004), the conditional effect of remedial indications increases to a 1.7-year reduction in time until compliance (marginal difference # 5). For the highest observed level of government accountability (United Kingdom in 2012), the sixth marginal difference suggests a reduction in time until compliance of approximately 3.7 years, although this estimate is associated with considerable uncertainty because the states with the strongest accountability institutions receive remedial indications less frequently.Footnote 7

These results show that the efficacy of remedial indications hinges on there being at least a minimum level of government accountability. However, the substantially and statistically significant difference for respondent states with the median level of government accountability shows that remedial indications help extract timely compliance from some of the ECtHR's notoriously recalcitrant respondents. In theoretical terms, the interaction effect provides further evidence that remedial indications promote timely compliance by enabling pro-compliance actors to hold responding authorities accountable.

Conclusion

Courts act strategically to promote timely compliance with their judgments, but few scholars have investigated whether these strategies are effective. I demonstrate that the ECtHR has been able to promote faster compliance by indicating appropriate remedies. Importantly, remedial indications is a strategy that is available to a variety of courts. Future research may benefit from investigating the effectiveness of other judicial strategies, such as citation practices aimed at legitimizing judgments (Larsson et al. Reference Larsson2017; Lupu and Voeten Reference Lupu and Voeten2012) and strategies designed to generate public awareness (Staton Reference Staton2006; Krehbiel Reference Krehbiel2016).

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/9HKISQ and online appendices at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000292.

Acknowledgements

This work benefitted from support by the Research Council of Norway through its Centres of Excellence funding scheme, project number 223274. I am particularly grateful to Alice Donald and Anne-Katrin Speck for helpful discussions concerning the data collection. I also thank the Editor, four anonymous reviewers, Erik Voeten, Jon Hovi, Daniel Naurin, Matthew Saul, Silje Hermansen, Mikael Holmgren, Jan Petrov, Andreas Føllesdal, Geir Ulfstein, and Andreea Alecu for helpful comments and suggestions. Dongpeng Xia, Ella Adler, Olja Busbaher and Gianinna Romero provided valuable research assistance. The data, replication instructions, and the data's codebook can be found at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/9HKISQ (Stiansen Reference Stiansen2019).