F.R. Hodson (Reference Hodson1964, 105) once coined the term ‘negative fossil type’ to describe the then lack of evidence for British Iron Age burials in contrast to the continent. Since Hodson’s influential work much has changed, at least in some parts of the country. Starting in the 1980s, legislative changes have provided greater protection for archaeological resources, thereby resulting in a massive expansion in the quantity, and quality, of Iron Age data from north-west Europe (cf. Webley et al. Reference Webley, Vander Linden, Haselgrove and Bradley2012). This includes mortuary data (cf. Bradley et al. Reference Bradley, Haselgrove, Vander Linden and Webley2016). Today it is increasingly possible to discuss how chronological changes in the Iron Age mortuary record in Britain compare and contrast with those elsewhere in north-west Europe. This increase in data has permitted a number of regional and inter-regional studies to be conducted in recent years (Table 1). It is these which form the main datasets of this paper. This paper is structured according to a chronological narrative divided into three sections: Early Iron Age (EIA), Middle Iron Age (MIA), and Late Iron Age (LIA). The relationships between this chronological scheme and others used in north-west Europe are displayed in Figure 1. An interpretative summary is given at the end of each section, with a conclusion thereafter.

TABLE 1. SUMMARY OF THE STUDIES WHICH FORM THE PRIMARY DATASET OF THIS PAPER

Fig. 1. Relative chronologies of the regions discussed in this paper. Sources for individual regions: central and northern Britain (Haselgrove Reference Haselgrove, Hunter and Ralston2015, 119); all other regions (Moore & Armada Reference Moore and Armada2011a, fig. 1.7; Bradley et al. Reference Bradley, Haselgrove, Vander Linden and Webley2016, fig. 1.3)

As the mortuary dataset has expanded and been refined, so has the theoretical and technological toolkit available to interpret these data. Social structure, population mobility, and ritual can now be examined in ways which were either previously impossible or hampered by a lack of technological or theoretical progress. Social modelling has expanded to consider the possibility that a range of societies existed in the past, including heterarchical and matrifocal societies, and how such societies may be reflected in the mortuary record (Sharples Reference Sharples2010; Hill Reference Hill2011; Pope & Ralston Reference Pope and Ralston2011; Pope Reference Pope2021). The term ‘elite’ is avoided in this paper, as simple correlations between the quantity and/or opulence of grave goods and status risk applying a ‘one size fits all’ category to different societies (Hunter, 61 in Carter et al. Reference Carter, Hunter and Smith2010; Pope Reference Pope2021, 13). The way in which people of elevated status were portrayed in different societies likely varied and may not have been reflected in death (Hill Reference Hill2011, 248). Rather, the more objective term status burial is employed to refer to those burials which contain a greater range and variety of grave goods than was typical for the local culture (cf. Pope & Ralston Reference Pope and Ralston2011, 395).

Mobility studies have also developed, with population movement now recognised as a complicated process rather than a mono-directional event. Mobility is influenced by factors such as geography and the flow of information, typically involving two-way movement, and more often small in scale than large (Fernández-Götz Reference Fernández-Götz2020, 184). Regarding ritual, a key concept for this paper is Terje Oestigaard’s (Reference Oestigaard, Rasmus Brandt, Prusac and Roland2015) idea of the death myth. The death myth describes the grander cosmological or mythological scheme within which each mortuary ritual is conducted. Death myths can be experimental or traditional, but ultimately seek to normalise themselves in the minds of observers. They are intended to give a sense of control to the uncertainties in which the death of an individual can result (Nieuwhof Reference Nieuwhof2015, 76). Many Iron Age mortuary practices appear unusual to our modern, rationalist perspectives but would have made perfect sense within the ritual framework, or death myth, of past societies. It is this variety of mortuary practices which are now considered.

EARLY IRON AGE MORTUARY PRACTICES IN BRITAIN

EIA data are less attested than for later periods (Pope & Ralston Reference Pope and Ralston2011, 390; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2014, 28; Roth Reference Roth2016, table 4.2). This stems in part from a comparative lack of research into EIA mortuary practices (Pope & Ralston Reference Pope and Ralston2011, 390; Still, PhD thesis in prep.). Another factor influencing this pattern is that EIA settlement evidence is also less attested than for later periods. In the succeeding MIA settlements are a major source of mortuary data in some parts of Britain (Bradley et al. Reference Bradley, Haselgrove, Vander Linden and Webley2016, 278; Pope Reference Pope2021, 45). There is also the problem that EIA remains are usually unaccompanied by chronologically diagnostic material, while radiocarbon dates often span the Late Bronze Age (LBA)/EIA transition, making it difficult to determine if human bone dates to the EIA (Pope & Ralston Reference Pope and Ralston2011, 390; Still, pers. comm). Lastly, there is the issue of geology and soils, with western, central and northern Britain having acidic soils which are not conducive to the preservation of bone.

TABLE 2. SUMMARY OF TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF DEAL-TYPE BURIALS (AFTER LAMB Reference Lamb2020; Reference Lamb2021)

Even with these limitations a varied picture exists. One of the first observations is that formal inhumation burial was more common and widespread in the EIA than previously thought. From southern Britain are 21 burials from Dibble Farm, Somerset (Morris Reference Morris1988), and an 8th–5th century bc cemetery with nine burials (seven of which were dated to EIA) from Little Woodbury, Wiltshire (Powell Reference Powell2013, 4). A number of cave deposits are also known from Wiltshire, including seven individuals from Slaughterford (Moore Reference Moore2006, appx 3). In central Britain is a predominantly female cemetery from Melton, south Yorkshire (Fenton-Thomas Reference Fenton-Thomas2011), a number of potential cist inhumations beneath cairns/barrows from North Yorkshire (Pope & Ralston Reference Pope and Ralston2011, 390), as well as two potential formal inhumations from a re-used Bronze Age cairn at Manor Farm, Borwick, Lancashire (Olivier Reference Olivier1987, 177). From northern Britain ten EIA inhumations are also known from a cemetery at Dryburn Bridge, East Lothian, Scotland (Dunwell Reference Dunwell2007, 67).

These EIA formal inhumations exhibit traits from preceding periods of prehistory that are also found in many later burials. These include a tendency to be placed in flexed or contracted positions with crania orientated to the north (Giles Reference Giles2012, fig. 3.3; Roth Reference Roth2016, figs 6.2–3; Lamb Reference Lamb2018a, fig. 94). Archaeologically detectable grave goods are also largely absent; something observed in both MIA and LIA burials and in many contemporary near-continental examples (see below; Pope & Ralston Reference Pope and Ralston2011, 388; Harding Reference Harding2016, 170). Thus, although the increasingly attested formal inhumations of the EIA have been a surprise, they conform to a long-lived set of insular traditions.

EIA formal burials are not restricted to inhumations. A more limited number of cremation burials are also known. Southerly examples, numbering fewer than a dozen sites, display an easterly distribution, mostly around Cambridgeshire and Kent. This could reflect influences from contemporary communities in the Netherlands. This finds potential support from the site of Cliffs End Farm, Thanet, Kent. Strontium and oxygen isotopic analysis of inhumed remains at this site identified migrants within the population, with one EIA female, and five MIA individuals (including two females and a possible male) displaying chemical signatures consistent with growing up in an environment cooler than Kent (Millard, 226 in McKinley et al. Reference McKinley, Leivers, Schuster, Marshall, Barclay and Stoodley2014). A potential source for this latter group would be the north European plain, where cremation was prevalent. Alternatively, these southern cremation burials could represent the survival of LBA practices (O’Brien Reference O’Brien2014, 28), or isolated incidents of communities experimenting with death myths in response to to differing circumstances surrounding the death of individuals (Veit Reference Veit2013, 11; Roth Reference Roth2016, fig. 8.2). There are also three likely EIA cremation burials from Wales (Davis Reference Davis2017, table 1). A localised concentration of cremation burials, albeit only four sites, also comes from East Lothian, and appears to represent a tradition which lasted from the EIA until potentially as late as the 1st century ad (Armit et al. Reference Armit, Neale, Shapland, Bosworth, Hamilton and McKenzie2013, 96).

In addition to these burials is a range of human remains in various states from other, non-grave, contexts, including ditches, pits, and waterlogged sites (Sharples Reference Sharples2010, 258). One particularly remarkable find is a decapitated cranium with a preserved brain from Heslington East, North Yorkshire (770–460 cal bc; OxA-20677, 2469±421 bp; O’Conner et al. Reference O’Connor, Ali, Al-Sabah, Anwar, Bergström, Brown, Buckberry, Buckley, Collins, Denton, Dorling, Dowle, Duffey, Edwards, Faria, Gardner, Gledhill, Heaton, Heron, Janaway, Keely, King, Masinton, Penkman, Petzold, Pickering, Rumsby, Schutkowski, Shackleton, Thomas, Thomas-Oates, Usai, Wilson and O’Connor2011, 1643) which, unhelpfully, falls squarely into the Iron Age calibration plateau. Such remains, in particular individual bones (termed disarticulated remains), have long been considered more typical of Iron Age mortuary practices in Britain. Although better attested for later centuries, in particular the MIA, EIA examples of disarticulated, or articulated partial bodies, are known from as far apart as Jarlshof, Shetland (Tucker Reference Tucker2010, fig. 6.2), Goldcliff, Newport, south Wales (Davis Reference Davis2017, table 1), and the aforementioned Cliffs End Farm (McKinley et al. Reference McKinley, Leivers, Schuster, Marshall, Barclay and Stoodley2014, table 4.3) in Kent. An extensive body of literature exists which has sought to explain these remains (cf. O’Brien Reference O’Brien2014, 30; Harding Reference Harding2016, 95). There is not space here to revisit all these discussions, though a single interpretation for these remains is unlikely to reflect past realities. As Ulrich Veit (Reference Veit2013, 11) has argued, a variety of scenarios or causes of death likely led communities to employ different, death-specific mortuary practices. That said, determining the cause of death from skeletal lesions is very rarely possible (Cattaneo & Cappella Reference Cattaneo, Cappella, Schotsmans, Márquez-Grant and Forbes2017, 353).

TABLE 3. SUMMARY OF TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF SOUTH-WESTERN BURIALS (AFTER LAMB Reference Lamb2018A; Reference Lamb2021)

Table 4. CHRONOLOGICAL PHASES OF WELWYN BURIALS & THE MATERIAL CRITERIA USED TO DIFFERENTIATE BETWEEN THE PHASES (ADAPTED FROM STEAD 1967; FITZPATRICK Reference Fitzpatrick2007)

Of particular importance to interpreting these ‘other’ remains, is how archaeologists have conceptualised them. At the start of this section the word ‘formal’ was used to describe inhumations and cremation burials from graves, as is common practice (eg, Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick2007, 124; Pope & Ralston Reference Pope and Ralston2011, 390). There is a risk here that human remains from other contexts, or in different states (disarticulated, curated/mummified, bog bodies, etc) may be considered ‘informal’ or ‘non-formal’ (Pilcher et al. Reference Pilcher, Rissanen, Spichtig, Alt, Röder, Schilber and Lassau2013, 482; Harding Reference Harding2016, 22). In so doing there is the implication that these other remains were subject to less care post-mortem than individuals from graves and, by extension, were viewed as less important. This is not a problem restricted to the Anglosphere, with French and German literature having also grappled with the problem of distorting terms like sépultures de relégation and irregulären Bestattung, respectively (Delattre et al. Reference Delattre, Bulard, Gouge and Pihuit2000, 5; Veit Reference Veit2013, 11).

There is increasing evidence from taphonomic studies that these ‘other’ remains stem from extended, controlled post-mortem processes (Madgwick Reference Madgwick2008, 9; Redfern Reference Redfern2008, 294; Pankowská et al. Reference Pankowská, Šmejda, Tajer and David Rieger2017, 414). Some bog bodies also show anatomical traits suggestive of a privileged life, potentially having enjoyed elevated social status (Giles Reference Giles2020, 195). A few inhumations from pits also display features which would be considered ‘formal’, such as the torc worn by a 30-40 female from Great Houghton, Northamptonshire (550–190 cal bc; Beta-116571, 2320±60 bp; Footnote 1 Chapman Reference Chapman2001, 32). These remains are thus better viewed as products of a wider spectrum of death myths, rather than an ‘informal’ group stood in contrast to what our modern, rationalist beliefs might expect from a ‘formal’ mortuary ritual.

EARLY IRON AGE IRISH AND NEAR-CONTINENTAL MORTUARY PRACTICES

Beyond Britain’s shores the picture is no less varied. Turning first to Ireland, there is a comparable paucity of EIA human remains. This is a pattern observed throughout the Irish Iron Age, in spite of increased rates of fieldwork. Tiernan McGarry (Reference McGarry2008a, 245) calculated that between 0.002% and 0.05% of a likely population of 500,000 were provided with a burial. The standard rite, if such a term is applicable, was usually an unurned, unaccompanied cremation deposit; a tradition with Bronze Age origins. It is possible that some of the contemporary Welsh cremation burials may have been influenced by Irish practices, with the archaeological record suggesting close contacts between communities either side of the Irish Sea (Mallory Reference Mallory2017, 162). Other human remains are seemingly lacking. To the author’s knowledge, no dry or wet context inhumations date to this period, although there are disarticulated infant remains dated to 800–650 cal bc (UB-6661, 536±31 bp) from Glencurran Cave, Co. Clare (Dowd Reference Dowd, Finlay, McCartan, Milner and Wickham-Jones2009, 94). The fact these remains were discovered in the protective environment of a cave, and not Ireland’s generally acidic soils, suggests that unburnt human remains may have been more prevalent in the EIA.

Cremation is also the main archaeologically detectable rite for Brittany during this period and, as with Ireland, has Bronze Age origins. In contrast to Ireland, Breton cremation burials were urned and occasionally associated with metal grave goods. Inhumation burials are also attested, sometimes from the same cemeteries as cremation burials. There was an apparent expansion in the number of formal cemeteries between the 6th and 5th centuries bc (Gomez de Soto Reference Gomez de Soto and Guilane2009, 275). Whether this represents an arrival of new groups to the area, who adopted local practices, or (more likely) an increased expression of local practices in the face of change, is unclear (Vannier Reference Vannier2019, 170; Pope Reference Pope2021, 28). These early cemeteries are usually small (1–12 graves) and probably represent individual families. Larger sites are known, however, such as the cemetery from Quimper, Kerjaouen, Finistère which contained as many as 24 individuals (Villard-Le-Tiec et al. Reference Villard-Le-Tiec, Gomez de Soto and Bouvet2010, 86).

Throughout the Iron Age, Breton data are primarily recovered from the coast (Fig. 2). This reflects a combination of where excavations have occurred historically, combined with the local geology and acidic soil conditions. Cremation alters the chemical composition of human bone, lowering its pH value and thus making it more resistant to the effects of acidic soils. Combined with the fact that urns were regularly employed in EIA Breton cremations, this has aided in their preservation and identification. The inhumation burials which date to this period have survived due to fortuitous circumstances (Villard-Le-Tiec et al. Reference Villard-Le-Tiec, Gomez de Soto and Bouvet2010, 86, 96).

Fig. 2. Distribution of Iron Age cemeteries and burials in Brittany (after Villard Le Tiec et al. Reference Villard-Le-Tiec, Gomez de Soto and Bouvet2010, with additions)

Acidic soil conditions in western Lower Normandy may also explain the lack of mortuary data for this region (Chanson et al. Reference Chanson, Delalande, Jahier and Le Goff2010, 57). To the east, a recent programme of excavations around Caen has identified 25 sites belonging to this period (ibid., fig. 1). The Hallstatt period here presents a pattern similar to that of Brittany; continued use of cremation, a limited number of sites, and a proliferation of cemeteries towards the start of the La Tène period (Chanson et al. Reference Chanson, Delalande, Jahier and Le Goff2010, 53). At the end of the 7th century bc inhumation emerged as a formal rite, as it did in rare instances of contemporary Britain, and among communities in the Paris Basin and Rhineland (Pope & Ralston Reference Pope and Ralston2011, 381). Interestingly, these burials are often recovered in flexed positions, as is more typical of Britain. That said, where orientation is known a south-westerly preference is observed. Late Hallstatt cemeteries are the largest in Lower Normandy, in stark contrast to the small cemeteries of contemporary Britain (Chanson et al. Reference Chanson, Delalande, Jahier and Le Goff2010, fig. 14). One example is Éterville Le Clos de Lilas, Calvados, where 52 individuals were buried. However, these are exceptional, and small cemeteries predominate throughout the Iron Age (ibid., 51). As in Britain, grave goods are neither abundant nor opulent. At Étreville, they amounted to 15 objects, consisting of brooches, bracelets, buttons, and earrings (Vauterin & Guillon Reference Vauterin and Guillon2010, fig. 8).

EIA mortuary practices in the Hauts-de-France have received less attention than those for the later La Tène period. In Picardy, burials are better attested in the Oise and Aisne départements, than they are in Somme. Inhumation is the most prevalent formal rite during this period, although cremation burials are also attested, with exclusively cremation and mixed cemeteries (Pinard et al. Reference Pinard, Delattre and Thouvenot2009, 101). For Hallstatt Final, 14 inhumation, four cremation and six mixed cemeteries are known from Picardy (Cayol Reference Cayol2018, 76). Four Hallstatt Ancien-Moyen burials with swords are also known from Picardy and appear to represent influences from status burials in central-eastern France (Cormier Reference Cormier2017, 291). However, the swords interred in these graves include bronze Gündlingen examples, thereby suggesting insular connections. In Hallstatt Final the Aisne-Marne culture, one of the largest and materially richest burial groups in western Europe, first developed. The sheer number of cemeteries and burials for this group (likely tens of thousands) is in stark contrast to almost everywhere else in northern France, Britain, and Ireland, suggesting a very different societal model and death myth for the Aisne-Marne group (Demoule Reference Demoule1999, 147; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Distribution of cantons with Aisne-Marne cemeteries, located predominantly between the rivers Aisne and Marne (after Demoule Reference Demoule1999, table 11.12)

The data for Belgium and the Netherlands contrast strongly with Britain. Here cremation was the preferred rite. At least 13 early Hallstatt status graves are known, mostly from Wallonia, with. associated grave goods including weaponry and horse tack (De Mulder Reference Mulder2017, fig. 1). Dutch Early Iron Age cemeteries contained hundreds of burials (Hiddink Reference Hiddink2014, 188; Nieuwhof Reference Nieuwhof2015, 62). Fokke Gerritsen (Reference Gerritsen2003, 193) has suggested that, as EIA communities in the Netherlands inhabited short-lived settlements, such cemeteries served as communal focal points. Additionally there are 47 Hallstatt Ancien-Moyen status burials (or potential burials) with copper alloy buckets, weapons, horse tack or wagon fittings known mostly from the central and eastern Netherlands (van der Vaart-Verschoof Reference Vaart-Verschoof2017, fig. 4.1.1).

An increasing number of inhumation burials are known from the central Netherlands, dating to c. 700–375 bc (Fig. 4; van den Broeke Reference Broeke2014, 163, 174). Five skeletons were subject to strontium isotope analysis, which found that three of them (all female) originated from outside of the central Netherlands. Combined with the non-local grave goods they were interred with, southern Germany, Alsace, and Switzerland were proposed as possible homelands for these women (ibid., 170). It has been suggested that inhumation was also more common in the southern Netherlands (where only two examples are known from among thousands of cremations), but that local soil conditions have destroyed the evidence (Kootker et al. Reference Kootker, Geerdink, van den Broeke, Kars and Davies2018, 596).

Fig. 4. Female inhumation from Grave 5, Lent Lentseveld, Nijmegan, Netherlands with copper-alloy head ornaments (nos 1-4) and iron ring (no. 5); 760–400 cal bc (GrA-47271, 2425±40 bp) (after van den Broeke Reference Broeke2014, fig. 110 with kind permission of P.W. van den Broeke).

EARLY IRON AGE BRITAIN, IRELAND AND THE NEAR CONTINENT IN SUMMARY

The EIA remains the least understood period for Iron Age mortuary data. Nevertheless, the picture has improved for many areas. The overall image is one of much regional variation, with the small, short-lived formal cemeteries of Britain, Ireland, and Brittany contrasting with the multi-generational sites from the Caen valley, Aisne-Marne culture, and Dutch Iron Age. Elsewhere in Oise, Aisne, and Lower Normandy there was an increase in cemeteries, some substantial in size, towards the end of the Hallstatt period, thereby mirroring trends also apparent in Brittany. The existence of cremation and inhumation burials in the same regions, in some cases at the same sites, further adds to this variation. This suggests a fluidity in ritual concepts, a range of death myths. Mortuary rituals were not rigid, regionalised practices, but malleable tools, possibly altered when necessary to respond to specific deaths in the community.

Non-locals may also have played a part in influencing mortuary practices and multi-isotopic studies are increasingly detecting these individuals in the EIA. These individuals have particular relevance when considering the EIA status burials and links between the Atlantic communities and those of central France and the Rhineland. Such burials are, at present, lacking for Britain and Ireland, suggesting that insular communities felt no need to reflect status in the burial record. Outside of the Aisne-Marne culture they are best represented for the Low Countries and, to a lesser extent, Picardy, where they display a fusion of more southerly practices, insular Atlantic traditions, and local traditions (De Mulder Reference Mulder2017, 342). The EIA thus sets the tone for the succeeding MIA.

MIDDLE IRON AGE MORTUARY PRACTICES IN BRITAIN

MIA mortuary practices in Britain are both better attested and examined. During this period a number of maritime burial groups emerged. The earliest of these are the Deal-type inhumations of eastern Kent (Figs 5 & 6). Absolute dates for two graves (Grave 1360033, Zone 12, East Kent Access 2 and Grave 1, Whitfield-Eastry Bypass Area 2), suggest a start date for this group as early as the end of the 5th century bc (Lamb Reference Lamb2020, table 3). The most unusual aspect of this group is the preference for the deceased to be placed in extended, supine positions, more typical of continental practices (Table 2). Combined with the proximity of these burials to northern France, and strong parallels between ceramics in early MIA Kent and early La Tène Hauts-de-France, it has been suggested that the Deal group was strongly influenced by near-continental practices (cf. ibid., 188).

Fig. 5. Distribution of Deal-type burials: 1. Mill Hill, Deal; 2. Zone 12, East Kent Access II; 3. A2 Activity Park; 4. Weatherlees Wastewater Treatment Works; 5. Saltwood Tunnel; 6. Church Whitfield; 7. Augustine House; 8. Leysdown Road; 9. Cottington Hill; 10. Thanet Earth, Plateau 8; 11. Tothill Street, Minster; 12. Brisley Farm; 13. Deal, Walmer; 14. Highsted, Sittingbourne; 15. Cemeteries 195118 and 126223, Zone 19, East Kent Access II; 15. Jullieberrie’s Grave, Chilham (after Lamb Reference Lamb2020)

Fig. 6. Burials from Mill Hill, Deal, Kent (after Parfitt Reference Parfitt1995, fig. 59 with kind permission of K. Parfitt).

Another group which originated in the MIA is the much studied Arras culture of the Yorkshire East Riding (Fig. 7; cf. Stead Reference Stead1991; Giles Reference Giles2012; Halkon Reference Halkon2020). The material culture of this group is overwhelmingly insular, with brooches, weapons, and vehicle components all belonging to British typologies. The same is true for the prevailing north–south orientation of most inhumations and flexed and contracted position of skeletons from pre-1st century bc burials. Two aspects of this group, however, have clear near-continental parallels: the use square barrows covering graves, and chariot burials (Stead Reference Stead1991, 184).Footnote 2

Fig. 7. Distribution of Arras culture cemeteries (after Stead Reference Stead1991; Giles Reference Giles2012)

Previously interpreted as the product of a continental migration from Champagne, by the end of the last century this idea was abandoned in favour of ideas of a small number of highly influential, potentially evangelical, individuals introducing continental practices to East Yorkshire (Stead Reference Stead1991, 184). Recent studies have further confirmed the predominantly insular nature of the Arras culture. These include a combined strontium and oxygen isotope analysis of seven chariot burials from the Wetwang, Garton Station, and Kirkburn cemeteries, which found no evidence for migrants. Indeed, only one of these individuals examined (Kirkburn 37) displayed evidence for a childhood spent outside of the Yorkshire Wolds (Jay et al. Reference Jay, Montgomery, Nehlich, Towers and Evans2013, 488).

It is generally the case that the chariots from Arras cemeteries were dismantled prior to burial, in contrast to the continental trend of burying complete vehicles. A programme of radiocarbon dating of chariot burials from Wetwang Slack also indicated that these burials date to the decades around 200 cal bc (Jay et al. Reference Jay, Haselgrove, Hamilton, Hill and Dent2012, 182), whilst a chariot burial from Barrow 89, Burnby Lane, Pocklington, East Riding was dated to c. 250 bc (Stephens & Ware Reference Stephens and Ware2020, 30). The Wetwang Slack and Burnby Lane burials therefore post-date the main phase of chariot burials in the near continent by several decades, if not a century in some areas (Fig. 8). Further support for this comes from Greta Anthoons’ (Reference Anthoons2021) study, which concluded that there is no single continental region to which the Arras chariot burials can be traced and thus a contemporary continental source for these burials should not be expected.

Fig. 8. Distribution and chronological phasing of La Tène chariot burials

Arguments could be made that future isotopic studies might detect an initial migrant element within the Arras group rather than their British-raised descendants; or that further chariot burials may be contemporaneous with the main phase of continental examples, for example the Ferry Fryston chariot, which may date to c. 350 bc (Boyle et al., 152 in Brown et al. Reference Brown, Howard-Davis, Brennand, Boyle, Evans, O’Connor, Spence, Heawood and Lupton2007). Additionally, some chariots in the Arras culture were buried complete, like The Mile, Pocklington example (Stephens & Ware Reference Stephens and Ware2020, 30). Nevertheless, the present evidence supports the idea that the Arras culture is an insular development, albeit one with clear inter-regional influences.

The Arras culture is not alone in producing MIA chariot burials. The earliest example in Britain comes from Newbridge, Edinburgh (Carter et al. Reference Carter, Hunter and Smith2010). Radiocarbon dated to 540–380 bc, with a preferred date of use and deposition of c. 475–400 bc (Hunter & Hastie, 52 in Carter et al. Reference Carter, Hunter and Smith2010), it possessed a curious fusion of continental and insular traits. For example, the burial contained two-part bits, typical of the continent but exceedingly rare in Britain and Ireland. At the same time the shrink fitting method to attach the iron tyres to the felloes, and likelihood the (unpreserved) inhumation was crouched, are British characteristics (Hunter, 39, 54 in Carter et al. Reference Carter, Hunter and Smith2010). Thus, much like the later Yorkshire examples, the Newbridge chariot was a local product, but one with undeniable links to contemporary continental practices (ibid.).

Mortuary groups are also known for Britain’s west coast during the MIA, like the recently identified inhumation tradition which existed in the Western Isles. Excluding Stornoway Airport, all burials so far discovered are on the western coast of the Outer Hebrides, as a result of coastal erosion (Fig. 9). The present distribution is almost certainly a product of fortuitous circumstance as much of the Western Isles have acidic soils. Indeed, it is possible that inhumations like these were more common in the Iron Age than the data suggest. Radiocarbon dates indicate that this group was long-lived, continuing as late as the 6th century ad (Cook et al. Reference Cook, Dunbar, Hunter Blair, Rhodes, Roy and Thomas2018, table 1). Recorded body positions and the use of cists are variable while grave are goods rare (Tucker Reference Tucker2010, 250). The significance of this group is that they represent an important addition for an area where mortuary evidence has long been considered lacking.

Fig. 9. Distribution of inhumation burials in the Western Isles: 1. Swainbost; 2. Galson. 3. Barvas; 4. Stornoway Airport; 5. Scarista; 6. Northon; 7. An Corran; 8. Udal; 9. Vallay; 10. Griminish; 11. A’ Ceardach Ruadh: 12. Hornish Point; 13. Drimsdale; 14. Pollacher (after Cook et al. Reference Cook, Dunbar, Hunter Blair, Rhodes, Roy and Thomas2018, fig. 1).

At the opposite end of Britain are the long-attested South-Western inhumations (Fig. 10 & Table 3). As with the Western Isles, cists were sometimes employed but not always (Nowakowski Reference Nowakowski1991, 213). The dataset for this group is much larger, with the poorly recorded site of Harlyn Bay, Cornwall producing c. 130 burials alone (Whimster Reference Whimster1977). Grave goods are also more abundant, though not ubiquitous. They also hint at trans-regional and trans-maritime contacts. These include 4th–3rd century bc Iberian-inspired brooches from Harlyn Bay and Mountbatten, Devon (Whimster Reference Whimster1977, figs 1–2; Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe1988, fig. 34.66–7), a coral decorated brooch from Trevone, Cornwall (370–100 cal bc; SUERC-81815, 2172±30 bp; Sophia Adams pers. comm.), three 1st century bc decorated copper-alloy mirrors from St Keverne, Cornwall (Jope-Rogers Reference Jope-Rogers1873, 272), Stamford Hill, Devon (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe1988, 87), and Bryher, Isles of Scilly (Johns Reference Johns2003), and a sword and scabbard from the latter. The mirror and sword burials belong to wider traditions discussed in greater detail below.

Fig. 10. Distribution of south-western inhumation burials: 1. Trethellan Farm; 2. Phillack, Hayle; 3. Little Trendeal, Ladock; 4. Penmenner, Landewednack; 5. Trevone, Padstow; 6. Carlatha, St Just; 7. St. Keverne, Trelan Bahow; 8. Harlyn Bay; 9. St Martins; 10. Porth Cressa, St Mary’s; 11. Bryher; 12. Old Man Island, Tresco; 13. Woodleigh; 14. Stamford Hill

The MIA also saw an increase in the number of cemeteries and isolated burials. Most of these cemeteries are restricted to a dozen or so burials, often lasting for little more than a few generations. As with the Deal group, and Irish data in general, radiocarbon dating has been vital identifying some of these burials and cemeteries as Iron Age (eg, Hey et al. Reference Hey, Bayliss and Boyle1999, table 1). Although primarily known from southern Britain, formal cemeteries and burials are recorded from central Britain (Barrowclough Reference Barrowclough2008, 205), and potentially northern Britain (eg, Sheridan Reference Sheridan2004, 174). They, like the larger mortuary groups, are presently the exception not the rule, despite the increasing numbers which have been identified. Dennis Harding (Reference Harding2016, 269) has suggested that later prehistoric communities in Britain transitioned between an emphasis on funerary monuments and settlements, ideas which echo Gerritsen’s (Reference Gerritsen2003) work on the relationship between Dutch Iron Age settlements and cemeteries.

One of the largest, and most curious, cemeteries is the example from Suddern Farm, Hampshire where as many as 300 adults, 80 children, and 180 infants were likely buried in a quarry between c. 500 and 250 bc (Fig. 11; Cunliffe & Poole Reference Cunliffe and Poole.2000, 168). Niall Sharples (Reference Sharples2010, 274) has identified a number of other sites in Wessex where inhumations have been discovered in quarries, suggesting Suddern Farm represents a larger example of a wider tradition. As he notes, in addition to the number of burials, the near-total absence of associated material (limited to an iron ring and a Hull and Hawkes 2C brooch) is surprising. The observation that many skeletons were missing elements may support ideas that disarticulated remains were obtained by re-opening inhumation burials (Sharples Reference Sharples2010, 277; Booth & Madgwick Reference Booth and Madgwick2016, 22).

Fig. 11. The inhumation cemetery at Suddern Farm, Hampshire (Cunliffe & Poole Reference Cunliffe and Poole.2000, fig. 3.93 with kind permission of B. Cunliffe).

There are also MIA examples of pit burials cemeteries, where the demographic profile of the deceased and, sometimes, the presence of grave goods, is comparable to formal cemeteries composed of graves (eg, Lambrick & Allen Reference Lambrick and Allen2004, 223; Brown et al. Reference Brown, Howard-Davis, Brennand, Boyle, Evans, O’Connor, Spence, Heawood and Lupton2007, 103; O’Brien Reference O’Brien2016, 17). From the site of White Horse Stone, Kent, is a likely example of a seated inhumation. These unusual burials are increasingly well-attested for the Iron Age, with numerous examples from France and Switzerland (Lamb Reference Lamb2018b, table 1).

By far the best attested MIA mortuary practices are human remains from settlement contexts, especially disarticulated remains. Although a variety of skeletal elements are recorded, crania and long-bones, likely due to a combination of cultural preference, their inherent robustness, and ease in identifying, tend to be the most commonly recorded elements (Sharples Reference Sharples2010, 290; Tucker Reference Tucker2010, fig. 6.7; Roth Reference Roth2016, fig. 6.16; Lamb Reference Lamb2018a, fig. 70). As in the EIA, where local conditions permit preservation, they are known from an increasing number of areas of Britain (eg, Armit & Ginn Reference Armit and Ginn2007, table 1; Tucker Reference Tucker2010, fig. 6.2; Schulting & Bradley Reference Schulting and Bradley2013, table 6; Davis Reference Davis2017, table 1). Indeed, their prevalence suggests that these remains, especially for the MIA, could be considered the standard rite(s) of the Iron Age, rather than the geographically and temporally restricted mortuary groups.

As noted, disarticulated remains are suggested to have been derived from inhumation burials. In Wessex, Sharples (Reference Sharples2010, 290) has suggested that the abundance of disarticulated remains represents the subversion of the individual. This argument conforms to the comparative paucity of inhumation burials in Wessex and the existence of sites such as Suddern Farm. Further support for Sharples’ ideas comes from the one part of MIA Britain with sufficient numbers of formal burials to potentially represent the majority of the population: the Arras culture. Here disarticulated remains are seemingly absent. Indeed, the only human remains from domestic contexts are a series of infant inhumations. This is despite recent programs of settlement excavations and local geology conducive to preserving human remains (Peter Halkon pers. comm.).

MIDDLE IRON AGE IRISH AND NEAR-CONTINENTAL MORTUARY PRACTICES

Regarding Britain’s neighbours, cremation burials are attested throughout this period in Ireland. However, in the early 2nd century bc formal inhumation re-emerged and continued into the Roman Iron Age. The geographical distribution of these burials, predominantly from the Meath–Dublin region, combined with the fact they were buried on their side in flexed or contracted positions led McGarry (Reference McGarry, Corlett and Potterton2010, 195) to suggest they represent British migrants, or communities with links to Britain. The movement of small numbers of Britons to Ireland would fit well within the wider evidence for contact between Britain and Ireland during this period (Mallory Reference Mallory2017, 199). Further evidence for Irish burials with British links occur in the form of 2nd century bc cremation burials from Fore, Co. Westmeath and Ballydavis, Co. Laois. The former was buried with a finely crafted copper-alloy bowl of south-west British type, the latter with an enamelled copper-alloy box, the closest parallel for which is the so-called ‘bean tin’ from Wetwang Slack grave 454 (McGarry Reference McGarry2008b, 219).

Bog bodies are also attested, with five examples certainly or likely dating to this period: Derrymaquirk, Gallagh, Clonycavan, Old Croghan, and Kinna-kinelly (McGarry Reference McGarry2008a, fig. 78). A single explanation is unlikely for these examples, with only Clonycavan and Old Croghan exhibiting soft tissue damage from injuries. By contrast, Derrymaquirk may originally have been contained within a purpose dug grave and consisted of a female and infant associated with sheep/goat and dog bone (ibid., 224).

Data are lacking for Brittany in La Tène B–C1, with fewer than five cremation cemeteries currently known (Gomez de Soto Reference Gomez de Soto and Guilane2009, 275; Webley Reference Webley, Anderson-Whymark, Garrow and Sturt2015, 132). Although this could represent the adoption of archaeologically undetectable mortuary practices, the simplest explanation is that it results from Brittany’s hostile soils. Support for this comes from the La Tène B–C1 site of Voutré, Mayenne, an inland site where unburnt humans remains were discovered inside a karst cave (Villard-Le Tiec et al. Reference Villard-Le-Tiec, Gomez de Soto and Bouvet2010, 104). Formal inhumation burials and disarticulated remains are a feature of late La Tène Brittany (see below) but only where local conditions permit preservation of bone. It is quite possible that the origins of Brittany’s late La Tène inhumations lie in the mid-La Tène period (as is the case for the south-western inhumations on the opposite side of the Channel) but that the evidence has either been destroyed or is yet to be discovered.

In eastern Normandy some of the large cemeteries established in Hallstatt Final continued in use until the 3rd century bc. The layout of the inhumed in Lower Normandy changed and supine, extended inhumations became standard. It also seems that the dead were increasingly buried in shrouds, judging by the location of brooches; something observed in some contemporaneous Arras and potentially south-western Burials (Giles Reference Giles2012, 79; Lamb Reference Lamb2021, fig. 2). Starting in the 3rd century bc cremation became the dominant rite, although it is attested as early as Hallstatt Final (Chanson et al. Reference Chanson, Delalande, Jahier and Le Goff2010, 69). Earlier La Tène cremation burials were placed in a ceramic vessel, while later examples appear to have been buried in organic containers (eg, Le Goff Reference Le Goff2002, 400; Lefort & Rottier Reference Lefort and Rottier2014, 22). These later La Tène cemeteries are much smaller in size, with few having more than 20 burials (Chanson et al. Reference Chanson, Delalande, Jahier and Le Goff2010, 54).

An important site from Normandy is the early mid-La Tène chariot burial from Orval Les Pleines. It is the only unambiguous La Tène chariot burial from Normandy (at Mondeville l’Étoile iron tyre parts were interpreted as a plundered grave; Lepaumier et al. Reference Lepaumier, Giazzon and Chanson2010, 331). The significance of this burial is that it dates to the period after the main phase of early La Tène chariot burials, thereby making it contemporaneous with the Wetwang Slack examples. Another remarkable mid-La Tène site from Upper Normandy is the sanctuary at Fesques, Seine-Maritime, where a row of shallow pits containing pedal phalanges has been interpreted as the remains of a 3rd century bc corpse gallery (Mantel Reference Mantel1997). Seated burials are also attested (Lamb Reference Lamb2018b, table 1), and inhumations are likewise recovered from ditches (Mantel et al. Reference Mantel, Devillers and Dubois2002, 10). Disarticulated remains are also recovered from domestic contexts, as they are in contemporary Britain, although it is possible these disarticulated remains result from disturbed burials (something hinted at by the presence of cremated bone; (Chanson et al. Reference Chanson, Delalande, Jahier and Le Goff2010, 61–8).

Off the coast of Normandy, in the Channel Islands, a long-lived tradition of formal inhumation burial appears to have been established. Previously thought to be a phenomenon of the 1st century bc, excavations at King’s Road, Guernsey suggest that such burials may date to as early as the 4th century bc (de Jersey Reference Jersey2010, 299). As with the Deal-type inhumations, the King’s Road cemetery displays a curious combination of continental and insular practices. The deceased were positioned supine and extended, with grave-goods more typical of near-continental burials. However, of the 22 burials at the cemetery, 16 were orientated towards the north, in the insular tradition.

In the Hauts-de-France, as in some parts of Britain and Normandy, inhumations are known throughout this period and are most prevalent in the 5th and 4th centuries bc, particularly in Picardy where they represent the standard formal rite (Pinard et al. Reference Pinard, Dessenne, Gaudefroy and Gransar2010, 37). Like contemporary Norman cemeteries, some burials display characteristics traditionally thought of as being insular: flexed and contracted body positions with a preference for northward orientation. Indeed, British influences may be observed in Graves 182 and 184 from Etaples-sur-Mer Pièce à Liards, Pas-de-Calais, in the form of two ring-headed pins of insular type (Henton Reference Henton2011, 69). To the author’s knowledge, these are the only examples of insular ring-headed pins yet found on the continent.

The Aisne-Marne culture also witnessed its materially richest phase, including the chariot burials which were long thought as the source of the Arras examples. The Aisne-Marne had ceased by the mid-3rd century bc, with the final phase (Aisne-Marne IVA) witnessing a rupture with preceding traditions in terms of the location of cemeteries and associated grave goods (Demoule Reference Demoule1999, 149). With the end of the Aisne-Marne culture the tradition of chariot burials in northern France became a rarer, more dispersed practice. In north-east France it appears to have been partially succeeded by one of graves with horse tack and vehicle fittings; a practice that was later adopted in Britain (Ginoux et al. Reference Ginoux, Sévérin and Leman Delerive2009, 213–5; Fig. 12; see below).

Fig. 12. Distribution and chronological phasing of burials with pars pro toto vehicle burials and equestrian equipment

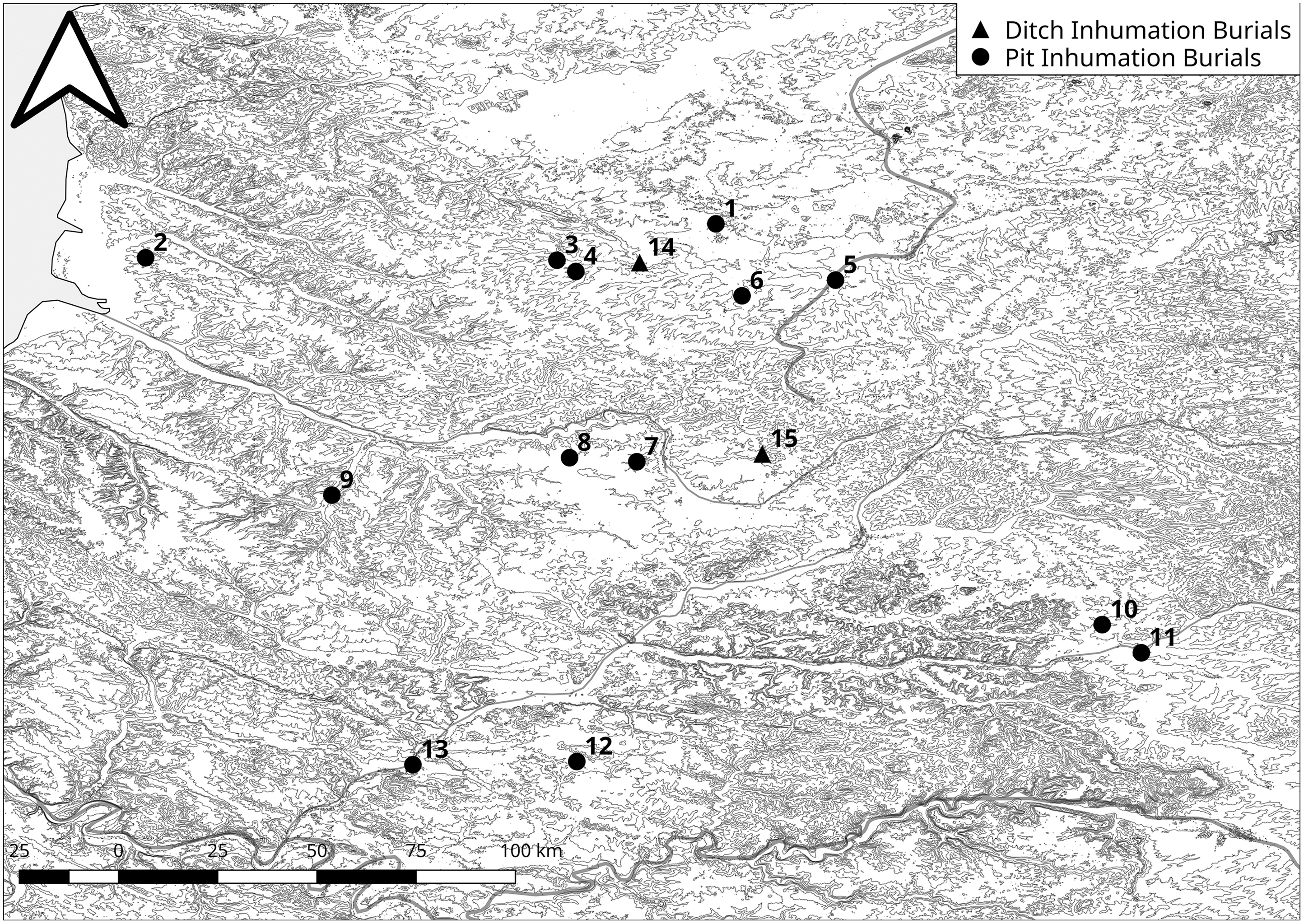

At start of the La Tène period, almost all Hauts-de-France inhumation burials from cemeteries were positioned supine and extended (Pinard et al. Reference Pinard, Dessenne, Gaudefroy and Gransar2010, 42). In terms of other contexts, Pinard et al. (Reference Pinard, Delattre and Thouvenot2009, 109) recorded only two pit burials from the 5th and 4th centuries bc, with three individuals between them. After La Tène B2, inhumations from pits and ditches are better attested, and appear to be mutually exclusive at settlements (Fig. 13). In contrast to the majority of inhumations from contemporary cemeteries, pit inhumations were typically positioned in flexed or contracted positions, as in Britain. Between La Tène A1 and B2 the position of dress fittings in inhumation graves suggests there was a shift from interring inhumations in shrouds to dressing them in funerary garb; the opposite of contemporary Normandy though commonplace in the Arras culture (Pinard et al. Reference Pinard, Dessenne, Gaudefroy and Gransar2010, 42). The prevalence of inhumation declined rapidly between the mid-4th and mid-3rd centuries bc, with cremation burials increasingly recorded, especially for the west of Picardy. During the mid-La Tène period two-thirds of cremation burials were placed in urns (Pinard et al. Reference Pinard, Delattre and Thouvenot2009, 102, fig. 2, 103, fig. 5). Cremation burials also become increasingly visible archaeologically in Nord Pas-de-Calais from c. 250 bc (Oudry-Braillon Reference Oudry-Braillon2009, 61, table 1; Devriendt et al. Reference Devriendt, Leroy-Langelin and Sergent2012, 92). This coincides with significant changes in the ceramic forms and items of personal adornment found in Picardy graves.

Fig. 13. Distribution of pit and ditch inhumation burials in the Hauts-de-France: 1. Lauwin-Planque; 2. Vron; 3. Duisans; 4. Dainville; 5. Hordain; 6. Sauchy-Lestrée; 7. Fresnes-Mazancourt; 8. Framerville-Rainecourt; 9. Loeuilly; 10. Amifontaine; 11. Menneville; 12. Baron; 13. Boron-sur-Oise; 14. Fampux; 15. Vermand (after Devriendt et al. Reference Devriendt, Leroy-Langelin and Sergent2012, fig. 1)

Disarticulated remains are a feature of the Hauts-de-France mid-La Tène mortuary record. The most striking examples of these remains come from Picardy’s Belgic sanctuaries. The largest dataset is from Ribemont-sur-Ancre, Somme, which produced over 10,000 human remains, including a remarkable ‘ossuary’ where 2000 long bones were interlaced. Curiously, only six cranial elements (a fragmented mandible, a piece of temporal bone, and four teeth) were excavated at the site, thus indicating that a preference for certain skeletal elements was practised. By contrast, at the broadly contemporary sanctuaries of Montmartin and Gournay-sur-Aronde, cervical vertebrae and cranial elements were over-represented (Duday Reference Duday1998, 116). This selectivity echoes the British disarticulated data, even if the Picardy examples originated within different ritual frameworks and from vastly different site types.

In Flanders, data are scarcer for the period c. 500–250 bc, with the large communal cemeteries of the 8th–6th centuries bc having been abandoned (van Beek & De Mulder Reference Beek and Mulder2014, 303; Leman Delerive Reference Leman Delerive2014, 125). By contrast, the south of Belgium has produced several early La Tène chariot burials belonging to the wider early La Tène tradition. Two 5th century bc chariot burials are also known from the Netherlands: Nijmegen (Bloemers Reference Bloemers, van Bakel, Hagesteijn and van de Velde1986) and a recently discovered example from Heumen, Gelderland (Roymans et al. in prep.). In contrast to other examples, but in keeping with local practices, both were cremation burials. The large, communal cemeteries of the Early Dutch Iron Age were also abandoned with the transition to Dutch Middle Iron Age, as in Flanders. Urns are present in limited frequency, although it appears organic containers were preferred (Hiddink Reference Hiddink2014, 188; Nieuwhof Reference Nieuwhof2015, 62). Radiocarbon dates from the aforementioned inhumation burials from the central Netherlands indicate that these burials continued to be created.

Outside of these cemeteries, the data display a comparable level of variation to some areas of contemporary Britain. Inhumations from pits are known from the Dutch coast and north-east (Kootker et al. Reference Kootker, Geerdink, van den Broeke, Kars and Davies2018, 595), while disarticulated bones are recorded from pits in the north-east (Le Brun-Ricalens Reference Le Brun-Ricalens2014, 167, fig. 9; Nieuwhof Reference Nieuwhof2015, 147). At least one Dutch MIA inhumation burial is known from the northern Terps region. This contrasts with the eight crania radiocarbon dated to this period, leading Nieuwhhof (ibid.) to remark that, as in parts of contemporary Britain, the practice of inhumation was the exception. In the Drenthe plateau in the north, human remains are found associated with similar variety of material culture recorded in southern Britain and France (animal bones, ceramic sherds, loom weights etc). Several bog bodies are also known from this period, all from the Drenthe province. A tradition of seated burials may also have existed in this region, although the relationship between such burials and those from further south and west remains unexamined (ibid., 48; Lamb Reference Lamb2018b, 430).

MIDDLE IRON AGE BRITAIN, IRELAND AND THE NEAR CONTINENT IN SUMMARY

The MIA in Britain and the surrounding regions witnessed significant developments in the mortuary record. In Britain the emergence of a number of mortuary groups, some existing for centuries, is of particular note. First, they suggest a new role for the deceased in society, one in which a permanent, multi-generational cemeteries played a part. This in turn indicates a shift in prevailing death myths. The Arras and Deal groups are of particular note here, as continental influences are especially apparent in both of these. What prompted these communities, and those who created the Newbridge burial, to adopt foreign practices is unclear. Emulation? A desire to emphasise supposed ancestry? The observation that the Wetwang Slack chariots may all date to a single generation is particularly noteworthy. Perhaps a single generation of one family sought to elevate themselves in death above their contemporaries. This is something which finds echoes elsewhere on the near-continent, such as the cremated chariots from Nijemegan and Heumen and later inhumation chariot burials like the Orval example.

Other changes also suggest some communities underwent a change in how they viewed the body. The mid-La Tène shift from inhumation to cremation in northern France is perhaps the clearest example of this (although see Carr Reference Carr2007). The same may be said of the large quantities of disarticulated remains from some British hillforts and Belgic sanctuaries. Similarly, bog bodies from Ireland, pit burials, and seated burials, suggest a range of death myths and attitudes to the dead. At the same time, established practices continued, such as the rite of cremation in the Netherlands and Ireland, or the insular preference for flexed inhumation. Where evidence for mortuary remains is not forthcoming, such as Brittany and parts of Britain, this should not be seen as the absence of mortuary traditions. Rather, local, hostile soil conditions or the existence of archaeologically invisible mortuary practices are more likely.

LATE IRON AGE MORTUARY PRACTICES IN BRITAIN

The LIA is also a period of change and continuity. The south-western and Deal groups continued and would continue into the Roman period. By contrast, the cemeteries of the Arras culture were abandoned in the 1st century ad. The final phase of the group saw the creation of smaller cemeteries, with the deceased often orientated east–west, in supine, extended positions, and sometimes beneath circular barrows. It is also significant that swords are better attested for this period and that there is increased skeletal evidence for inter-personal violence. The communal bonds which had marked the earlier cemeteries were seemingly under stress (Giles Reference Giles2012, 152).

In southern Britain two new mortuary groups emerged. The earliest is the Aylesford group, and saw the widespread re-emergence of cremation (Fig. 14). Often referred to as the Aylesford-Swarling group after two eponymous cemeteries in Kent, I.M. Stead (Reference Stead, Sieveking, Longworth and Wilson1976, 401) argued that the ‘Swarling’ component of the name was superfluous. This was because there were no discoveries from the Swarling cemetery which differed sufficiently from those at Aylesford to justify using both names. For this reason, the group is referred to simply as the Aylesford group in this paper. More contentious has been the date for the start of this group (cf. Lamb Reference Lamb, Pavúk, Klontza-Jaklová and Harding2018c, 341).

Fig. 14. Distribution of Aylesford burials of all types

New discoveries since the 1980s indicate that a pre-50 bc date for the start of the Aylesford group is likely. From Baldock, Hertfordshire, is a burial containing a cauldron, two bronze vessels, a pair of firedogs, two metal-plated wooden buckets, and a Dressel 1a amphora with an ascribed date of c.100–50 bc when discovered (Stead & Rigby Reference Stead and Rigby1986, 53). An increasing number of Aylesford burials with Nauheim and Almgren 65-type brooches have also been discovered (eg, Parfitt Reference Parfitt1998, 346, figs 3–4; Dawson Reference Dawson2005, 129). Both brooch types are conventionally dated to pre-50 bc on the continent (Schönfelder Reference Schönfelder2021, 123). A programme of Bayesian radiocarbon dating at the (non-Aylesford) cremation cemetery at Westhampnett, West Sussex appears to confirm that the Nauheim and Almgren 65 fibulae from the site date to the earlier part of the 1st century bc (Fitzpatrick et al. Reference Fitzpatrick, Hamilton and Haselgrove2017, 374). A similar study at the King Harry Lane, Hertfordshire, the largest Aylesford cemetery ever discovered (n=455 cremation burials) also indicates that a sizeable part of the cemetery dates to pre-50 bc, contrary to published dating of the site (Adams & Hamilton in prep.).

The other aspect of the Aylesford group which has been much studied are the materially richest burials of the group: Welwyn-type burials. These burials are defined by the inclusion of at least one amphora (Stead Reference Stead1967). They are divided into two chronological phases (Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick2007, 126; Table 4). Long-thought to be restricted to north of the Thames, the recent discovery of a Welwyn-type burial from Windabout Copse, Hampshire, provides the first certain example outside this region (Wheeler & Pankhurst Reference Wheeler, Pankhurst, Fulford, Barnett and Clarke2016, 14; Fig. 15). Although plundered in antiquity, there are sufficient indicators to identify it as a Welwyn grave of the Lexden phase (ibid., 15–16).

Fig. 15. Distribution of Welwyn-type burials and their chronological phases

Around the time of the first Lexden phase burials, the Durotrigian group emerged in southern Dorset (Fig. 16; Table 5). The two largest cemeteries come from the (by then abandoned) hillfort ramparts of Maiden Castle (n=52; Wheeler Reference Wheeler1943) and Poundbury, Dorset (n=56; Farwell & Molleson Reference Farwell and Molleson1993, 7; Stewart & Russell Reference Stewart and Russell2017, 170). Otherwise, Durotrigian cemeteries tend to be small scale and associated with rural settlements. It is worth noting that Durotrigian burials from hillforts were, on average, associated with fewer grave goods (mean=2.2) than those from rural settlements (3.45; Lamb Reference Lamb2018a, 244). As with Deal and Aylesford burials, the Durotrigian group continued into the Roman period. Of particular note in this group are the discovery of rich mirror burials at Portesham (Fig. 17; Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick1996) and Langton Herring, Dorset (Russel et al. Reference Russel, Smith, Cheetham, Evans and Manley2019), both of which were biologically female.

Fig. 16. Distribution of Durotrigian burials in Dorset: 1. Langton Herring; 2. Portesham; 3. Whitcombe; 4. West Bay, Bridport; 5. Broadmayne; 6. Burton Bradstock; 7. Blashenwell Tufa Pit, Corfe Castle; 8. Dorchester; 9. Pin Knoll, Litton Cheney; 10. West Stafford; 11. Wyke Reservoir, Weymouth; 12. Jordan Hill, Weymouth; 13. Sutton Poyntz, Weymouth; 14. Maiden Castle; 15. Wynford Eagle; 16. Alington Avenue; 17. Wareham House; 18. Max Gate, Dorchester; 19. Tollard Royal. 20; Winterbourne Kingston; 21. Poundbury (after Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick1996, fig. 1)

Table 5. SUMMARY OF TYPICAL CHARACTERISTICS OF DUROTRIGIAN BURIALS (AFTER LAMB Reference Lamb2018B; Reference Lamb2021)

Fig. 17. Mid-1st century ad Durotrigian burial from Portesham, Dorset (after Fitzpatrick Reference Fitzpatrick1996, fig. 2 with kind permission of the Dorset Natural History & Archaeological Society)

Burials with decorated copper-alloy mirrors are a tradition which emerged in the 1st century bc and exist within the south-western, Durotrigian and Aylesford cultures. They are a strictly British tradition and, although complete (Nijmegan) and partial (Compiègne, Oise; Ballybogey, Co. Antrim) decorated copper-alloy mirrors are known from the continent and Ireland, they do not come from burials. Melanie Giles and Jody Joy (Reference Giles, Joy and Anderson2007) have suggested that the women buried with these objects were powerful individuals, potentially soothsayers. This finds support in the presence of a forged Roman denarius from the Langton Herring burial in Dorset, seemingly modified to serve as an amulet (Russel et al. Reference Russel, Smith, Cheetham, Evans and Manley2019, 213). This tradition of mirrors has been considered to be the female equivalent of a tradition of sword burials which first emerges c. 250 bc with Mill Hill, Deal grave 112, and are known as far north as Falkirk (Inall Reference Inall, Erskine, Jacobsson, Miller and Stetkiewicz2016, 51). In southern Britain most examples date to the LIA, a time when historical and numismatic evidence suggest that Britons were serving in Belgic, Gallic, and Roman armies. This, combined with the archaeological and isotopic evidence for oversees movement at the North Bersted, West Sussex burial, may indicate the emergence of a veteran identity among some communities.

Outside of these groups LIA mortuary data remain varied. A number of short-lived formal inhumation cemeteries and isolated burials were created, predominantly in southern Britain (eg, Evans et al. Reference Evans, Holbrook and McSloy2006, 7; Leivers & Gibson Reference Leivers and Gibson2011, 6; Andrews et al. Reference Andrews, Harding and Dinwiddy2015, 201), but also in northern Britain (eg, Rhodes & Jones Reference Rhodes and Jones2016, 106). A remarkable recent discovery is a chariot burial from Pembrokeshire (Adam Gwilt, pers. comm.). As has been argued above, local geological conditions likely explain the comparative paucity of Iron Age human remains found in Wales (Davis Reference Davis2017, table 1). The significance of the Pembrokeshire burial is that it dates to the 1st century ad. It is thus the only chariot burial from north-west Europe from this period. Furthermore, although pars pro toto vehicle burials are known from southern Britain in the 1st century ad, the tradition of burying entire vehicles appears to have ceased at the start of the 2nd century bc, both in Britain and on the near-continent. Why a community in 1st century ad Wales should have opted for such a distinctive rite is unclear. Direct influence from contemporary groups can, on present evidence, be ruled out. It could represent an experiment in the aforementioned death myth. The Pembrokeshire burial may equally be an example of a curated rite, replicating a tradition known from folklore, perhaps in a similar way to how Irish Viking era texts reference earlier, Iron Age, traditions, including the use of chariots.

In Wessex, and southern Britain in general, the quantity of disarticulated remains known from the archaeological record declined (Roth Reference Roth2016, fig. 4.8; Lamb Reference Lamb2018a, fig. 20). However, this is primarily a result of a change in settlement pattern, whereby the hillforts of the MIA, one of the main sources of disarticulated remains, were increasingly abandoned. Outside of these, disarticulated remains continued to be a feature of the archaeological record to varying extents. At Glastonbury Lake Village, Somerset, for example, LIA disarticulated remains were the only human remains recovered, aside from a small number of infant inhumations from domestic contexts. Thus, the increase in inhumation burials in southern Britain should not be considered a universal trend. Disarticulated remains continued to be a feature of the archaeological record for western, central, and northern Britain (Tucker Reference Tucker2010, table 6.3; Marlow et al., 324 in Haselgrove Reference Haselgrove2016; Davis Reference Davis2017, table 1). This includes disarticulated remains from areas sometimes considered lacking in Iron Age mortuary data, such as Lincolnshire (Chowne et al. Reference Chowne, Cleal, Fitzpatrick and Andrews2001, 77).

Other mortuary practices, though less well-studied than the aforementioned formal groups are also attested. They include pit burial cemeteries, pit and ditch burials more typical of preceding EIA and MIA traditions (eg, Powell et al. Reference Powell, Allen, Chapman, Every, Gale, Harding, Knight, McKinley and Stevens2005, 276), and an additional example of a seated pit burial from Dunbar, East Lothian (Lamb Reference Lamb2018b, table 1, no. 6). Bog bodies and ‘wet heads’ are also attested for this period. The fact that many of these date to the very end of the Iron Age/start of the Roman period, when central and southern Britain were being incorporated into the Roman Empire, has been interpreted as a sign that these practices may represent a response to stress and uncertain times (Giles Reference Giles2020, 212).

LATE IRON AGE IRISH AND NEAR-CONTINENTAL MORTUARY PRACTICES

Contemporary with the LIA British sword burials is Ireland’s only certain sword (and shield) burial: Lambay Island, Co. Dublin. The presence of a British-style beaded torc at the site has been argued to represent a migrant population, if not refugees, from Britain (Rynne Reference Rynne1976, 242). The Lambay Island cemetery falls within the broader, Meath-Dublin distribution of British-influenced inhumation burials discussed above. The idea that 1st century ad Britons would choose the Dublin coast as a place to move lends itself well to current migration theory ideas of small groups of individuals moving to areas of which they already have knowledge (Fernández-Götz Reference Fernández-Götz2020, 184). Rare examples of disarticulated remains also date to this period, including a femur and female cranial fragment dated to the 1st century bc/ad from Drumanagh, Co. Dublin (Baker Reference Baker2019, 29), and a curated cranial fragment form Raffin Fort, Co. Meath (80 cal bc–cal ad 210; AA-10281, 1975±50 bp; Newman et al. Reference Newman, O’Connell, Dillon and Molloy2007, table 1).

The data for late La Tène Brittany are more abundant than for preceding centuries. Inhumations in proximity to settlements have also been recorded, such as the La Tène D sites of Kerne and Goulvars, Quiberon. At Goulvars an infant inhumation displayed cut marks to the lower limbs, leading the authors to draw parallels with ‘foundation sacrifices’ observed in Britain (Tanguy et al. Reference Tanguy, Briard, Hyvert, Le Bihan and Menez1990, 150). There are also human remains from the La Tène C2–D cave site of Saint-Pierre-sur-Erve Grotte de Rochefort and souterrain at Plougasnou, Finistère (Le Goffic Reference Le Goffic1997, 45; Villard-Le-Tiec et al. Reference Villard-Le-Tiec, Gomez de Soto and Bouvet2010, 91, fig. 6; 93, fig. 10). As with the human remains from the mid-La Tène cave at Voutré, these late La Tène human remains hint at the existence of a variety of mortuary practices in Brittany, the evidence for which has been lost due to local soil conditions.

On Guernsey the tradition of inhumation continued, although burials with weapons appear to have become more common, as was the case in contemporary southern Britain, the Arras culture, along the lower Seine, and in Picardy (eg, Mare Reference Mare2010, 47; Breton Reference Breton2012, fig. 15). In nearby Normandy mid-La Tène patterns continued. Cremation was the preferred formal rite, with cemeteries often small (fewer than 20 individuals) and in close proximity to settlements. In contrast to Aylesford burials, but akin to the contemporary Westhampnett cemetery, soft-sided containers, presumably made of leather or textiles, appear to have been preferred for the cremated bone (eg, Blancquaert Reference Blancquaert2002, 392). A remarkable (now stolen) urn/container was found at Mailleraye-sur-Seine, Seine-Maritime: a Syrian glass bowl (Lequoy Reference Lequoy1993, 121).

Normandy’s only pit inhumation also dates to this period, with three adults inhumed at the site of Notre-Dame-de-l’Isle La Plaine du Moulin à Vent, Eure (Aubry & Honoré Reference Aubry, Honoré and Delrieu2009, 35). Arguably the most interesting site, within the context of the British Iron Age, is the settlement and associated mixed cemetery from Urville Nacqueville, Manche (Lefort & Rottier Reference Lefort and Rottier2014). Although dating to La Tène D1, and thus preceding the Durotrigian group on present evidence, the presence of four flexed inhumations associated with lignite bracelets and three roundhouses, finds its closest parallels in LIA Dorset (ibid., 30; Fig. 18).

Fig. 18. 1st century bc inhumation burials from Urville-Nacqueville (after Lefort & Rottier Reference Lefort and Rottier2014, fig. 37 with kind permission of A. Lefort)

Further east, in the Hauts-de-France, the trend towards familial-sized cremation cemeteries continued. A number of status graves also emerged, with an emphasis on feasting and, to a lesser extent, equestrianism in the form of the pars pro toto vehicles or horse tack mentioned above. Some of these are contemporary with the Welwyn group (cf. Ginoux et al. Reference Ginoux, Sévérin and Leman Delerive2009; Sueur Reference Sueur2018, 21). In contrast to the start of this period, late La Tène mortuary data are derived overwhelmingly from the Somme department, with urns now outnumbering perishable containers by a ratio of 2:1; a trend paralleled in contemporary Aylesford burials (Pinard et al. Reference Pinard, Delattre and Thouvenot2009, fig. 13). Inhumation continued to decline in frequency in Picardy, representing less than one in ten burials by La Tène D (Pinard et al. Reference Pinard, Delattre and Thouvenot2009, fig. 2; 2010, fig. 2).

Pinard et al. (Reference Pinard, Delattre and Thouvenot2009, fig. 5) observed that cremation burials in Picardy underwent a rapid decline in frequency during La Tène D. It is possible this decline relates to a corresponding abandonment in La Tène D2 rural settlements, which Haselgrove (Reference Haselgrove2007, 508) linked to increasing oppida populations. Considering the revised dating for the Aylesford culture, it is not impossible that some members of these communities may have also crossed the Channel to escape this apparent social instability. Disarticulated remains also continued to be a recurring find from a variety of Picardy domestic contexts, occurring as late as La Tène D2 (eg, Fémolant Reference Fémolant1997), with cranial elements being the dominant element (31 of 54 remains dated to La Tène C1/2–D1; Joseph Reference Joseph2009, 40). Sanctuaries, however, were no longer the main foci for such remains.

The picture across Belgium in the late La Tène period is more comparable to northern France and southern Britain in terms of the availability of data, though not treatment of the deceased, for which the closest parallels are again the Netherlands (Leman Delerive Reference Leman Delerive2014, 134). Disarticulated remains are also attested, including a collection of decapitated heads found in a La Tène D votive cave at Han-sur-Lesse, Namur (Delaere & Warmenbol Reference Delaere, Warmenbol, Büster, Warmenbol and Mlekuž2019). In the Netherlands the general pattern observed in the Dutch MIA continued, with the mortuary record in the southern and central Netherlands dominated by small cremation cemeteries, with few grave goods. Much larger cemeteries also emerged during this period, albeit containing only a fraction of burials of the Dutch EIA cemeteries. Examples include Weert Molenakkerdeerf (124 burials) and Someren Waterdael (225; Hiddink Reference Hiddink2014, 190). As with some contemporary Aylesford, Deal, and Durotrigian cemeteries, some of these sites continued in use into the Roman period. Additionally, the Meuse–Waal confluence also became a foci for the deposition of certain objects, including human remains of various ages, thereby echoing practices observed for the Thames (Nieuwhof Reference Nieuwhof2015, 59)

LATE IRON AGE BRITAIN, IRELAND AND THE NEAR CONTINENT IN SUMMARY

At first glance the LIA could be viewed as a period of increased homogeneity in the mortuary record, at least in southern Britain. In north-eastern France and south-eastern England cremation had become the preferred rite, while inhumation burials were created either side of the western Channel. The artefactual record attests to the transmission of ideas and objects and there is isotopic evidence for the movement of people within, and to southern Britain (Taylor Reference Taylor2014, 120; Redfern Reference Redfern2016, 12). A variety of mechanisms, ranging from trade, to fosterage, marriage or military clientage were likely responsible (Karl Reference Karl2005, 264).

The Aylesford group, with its clear continental affinities has, on occasion, been ascribed to continental migrants (Lamb Reference Lamb, Pavúk, Klontza-Jaklová and Harding2018c, 339). There are clear parallels between Aylesford and contemporary Belgic graves, including a similar range of grave goods and the preference for urned cremation in the 1st century bc. New studies indicate that cremated bone can be used for strontium isotopic analysis (Harvig et al. Reference Harvig, Frei, Price and Lynnerup2014; Jernejčič & Price Reference Jernejčič and Price2020). It may thus be possible to test for the presence of non-locals within Aylesford cemeteries, although determining their origin is a different matter (Kootker et al. Reference Kootker, Geerdink, van den Broeke, Kars and Davies2018, 596).

Important differences remain, however, especially between the late La Tène status graves either side of the Channel. Both groups have much in common; the inclusion of items associated with feasting and Mediterranean imports, the near total absence of offensive weaponry, and some shared architectural features (Vannier Reference Vannier2020, 299). However, key differences may be observed. The first is chronological. The French examples pre-date the earliest British graves by 50 years; the first British example being the Baldock burial. Another is that certain objects found in the north-east French examples are absent from the British graves. For example, there is the tradition of horse tack in French graves from the 3rd century bc onward (see above). Only two Aylesford graves contained horse tack and both date to the 1st century ad (Lethbridge Reference Lethbridge1953, 31; Niblett Reference Niblett1999, 135).

A further difference is the arrangement of feasting equipment in Picardy, whereby objects like firedogs and cauldrons are placed centrally in the grave (eg, Cizancourt grave 3; Marcelcave Le Chemin d’Ignaucourt grave 9). Some authors have referred to this as a ‘functional arrangement’, implying such graves were arranged to emulate a feast (Pinard et al. Reference Pinard, Dessenne, Gaudefroy and Gransar2010, 47; Sueur Reference Sueur2018, 297). Excluding Baldock, this arrangement is not observed in Welwyn graves. Rather, the central position is occupied by items such as gaming pieces, litters, and wine paraphernalia. A likely reason for this is that the Welwyn example post-date the arranged functionally Belgic examples. However, it also indicates a different concept of what message the arrangement of a grave was intended to convey.

Another group of objects of note are swords. Most British graves with swords date to the LIA but they are, nevertheless, comparatively rare. Even the greatest concentration of swords in graves from Britain, the Arras group, counts only 40 graves (out of several thousand burials) for the group’s entire existence. As noted above, only one grave from Ireland, Lambay Island, is known to have contained a sword. Similarly, in the Hauts-de-France swords are, except for the Gallic War, never found in more than 15% of graves, and display a decline in prevalence over the course of the La Tène period (Desenne et al. Reference Desenne, Blancquaert, Gaudefroy, Gransar, Hénon and Soupart2009, fig. 8). In Normandy swords in later La Tène graves are also rare, with the majority coming from burials along the course of the Seine; a localised practice that continued into the Augustan period (eg, Mare Reference Mare2010, 47; Breton Reference Breton2012, fig. 15), and in some ways echoes the riverine distribution noted of burials with weapons in Britain (Inall Reference Inall, Erskine, Jacobsson, Miller and Stetkiewicz2016, 46). Swords from graves are also unknown from the Netherlands during this period, whilst those in Brittany they are almost as rare as in Ireland (Villard-Le Tiec et al. Reference Villard-Le-Tiec, Gomez de Soto and Bouvet2010, 97). As Nico Roymans (Reference Roymans and Roymans1996, 17) has suggested, this appears to have been a time Roman activity resulted in a rise in martial identities in north-eastern Gaul. This accords with the aforementioned ideas of a veteran idea developing in Britain during the 1st centuries bc–ad.

CONCLUSION

Iron Age mortuary practices, both in Britain and the surrounding regions display a combination of long-established traditions, geographically and chronologically interspersed by shorter lived practices. They are variable and volatile. Some of these acts seem to have been remarkably long-lived, such as the preference for cremation in Ireland and the Netherlands. Of particular note are chariot burials, which re-appear periodically in the archaeological record in different areas of north-west Europe, re-interpreted according to local practices. Others, such as the spread of cremation in northern France and Britain, beginning in the 3rd century bc, are more chronologically unified but nevertheless display much regional variation.

Indeed, regional variation is an important characteristic of mortuary data during this period. It includes the restricted distribution of burials like the Deal group (found only in eastern Kent), or the observation that the Oise valley in the Hauts-de-France represented a cultural border, with the cremation utilising groups to the west and north having greater affinity to Atlantic communities, and the inhumation traditions to the east and south being orientated to Alpine mortuary traditions (Pinard et al. Reference Pinard, Dessenne, Gaudefroy and Gransar2010, 38). Other differences of note include the way the inhumed dead were clothed. The La Tène Norman preference for shrouds contrasts with the Picardy evidence for funerary garb, while the evidence from MIA and LIA Britain suggest a variety of approaches between the different mortuary groups.

Status burials are a recurring feature of the archaeological record. However, they are geographically and temporally restricted. They are exceptional in this respect. This is not a phenomenon restricted to north-west Europe and may also be observed in central France and southern Germany (Metzler-Zens & Metzler Reference Metzler-Zens, Metzler, Müller-Karpe, Brandt, Jöns, Krausse and Wigg1998, fig. 4; Pope and Ralston Reference Pope and Ralston2011; Cormier Reference Cormier2017, 291). Lastly, there is the widespread evidence for a variety of human remains from different contexts and in different forms, ranging from disarticulated remains to seated burials and bog bodies. The sheer variety of data and the inter-regional nature of some evidence mean it becomes increasingly impossible to draw neat boundaries between different regions, as Hodson could in the 1960s. Instead, the evidence points to a range of death myths enacted through a kaleidoscope of rituals.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Professor Ian Armit (University of York), Dr Rachel Pope (University of Liverpool), Dr Matthew Knight (National Museums Scotland), Dr Melanie Giles (University of Manchester), Dr Nicky Garland (University of Durham), Dr Helen Chittock (Museum of London Archaeology) and the anonymous reviewers for comments and thoughts on the text. Special thanks also to Professor Nico Roymans (Vrije Universiteit/VU University Amsterdam), Dr Peter Halkon (University of Hull), Dr Adam Gwilt (National Museum of Wales), Dr Sophia Adams (University of Glasgow), Dr Philip de Jersey (States Archaeologist, Culture and Heritage; States of Guernsey), Emma Tollefsen (University of Manchester), Beverley Still (University of Durham) and Colin Wallace (University of Liverpool) for providing details of their unpublished research.