Introduction

Business education is over two centuries old in Europe. Although the first business schools were considered secondary schools and regarded with some disdain by universities, they gradually acquired university-level respectability during the twentieth century.Footnote 1 The post-World War II period is usually portrayed as an era of growth and development for business schools in both Europe and North America, as recently shown by both Pettigrew and McLaren.Footnote 2

The literature on the history of management education has largely centered on the rise of business schools rather than the history of their programs.Footnote 3 Indeed, numerous studies investigate business schools’ institutionalization processes, particularly the mimetic and standardizing effects of rankings and accreditation on the development of these schools.Footnote 4 Moreover, much of the literature offers analytically relevant accounts of the rise of business schools, especially in the United Sates, after World War II.Footnote 5 These studies mostly chronicle patterns of development and raise challenges about the future of management education. Similar analytical and historical treatment of the development of business schools in postwar Europe remain rare, with a few exceptions.Footnote 6 However, some studies have focused on the effects of the Bologna process on European business schools.Footnote 7 In the same vein, some scholars have discussed the domination of U.S.-style managerial education in Europe since the second part of the twentieth century. They demonstrate that this has manifested in a wide range of reactions in European schools, from imitation to hybridization to resistance to outright rejection of the U.S. model.Footnote 8

Thus, the history of curricula within European business schools from the middle of the twentieth century remains a relatively untouched topic. Enders calls on researchers to open up the “black box” of business schools to explore their evolution in greater depth for a more context-sensitive understanding.Footnote 9 Indeed, temporal data are necessary to appreciate not just how these determinants were developed but also how they were sustained over time.Footnote 10 This is why some authors encourage longitudinal studies to understand the emergence of specific field studies within business schools’ curricula.Footnote 11

This article focuses on the following research questions: Who are the key actors and what are the factors and processes in the evolution of European business school curricula? How do they interact to influence the dynamics of institutionalization? In exploring these questions, this study remedies three inadequacies in the current literature: (1) the scarcity of empirical studies on the evolution of business schools’ curricula in Europe from a processual perspective; (2) the lack of historical research dedicated to the rise of management, leadership, and entrepreneurship studies in their programs; and (3) scholars’ call for individual case studies on the institutionalization of business schools. My research investigates how a business school that was originally established for bookkeepers adapted its curricula to become a leading European management school. To analyze this evolution, I relied on a qualitative historical case study approach. Using a longitudinal analysis of the education systems at ESCP—a European business school with a rich empirical setting and a long tradition that dates back to the nineteenth century—I analyze the evolution of its curricula over time, especially from the late 1960s onward.

The article is organized as follows. The first section examines the case study’s details, sources, and methods. The second section analyzes ESCP’s curricula from the late 1960s onwards. The third section discusses the evolution, processes, and actors that influenced the evolution of ESCP’s curricula.

Case, Sources, and Methods

Empirical Setting

This research is based on a single case study devoted to ESCP for three reasons.

First, ESCP is an elite French business school that tops global rankings in the Financial Times, and in other listings. The school is neither part of an American institution nor located within a larger university in Europe. Thus, as a French grande école, ESCP offers organizational specificities comparable with American stand-alone business school.Footnote 12 More specifically, it is a consular business school owned by the Paris Chamber of Commerce (PCC), which has a say in the school’s budget and advises on its activities and programs. The ESCP is selective in which students it accepts based on entrance examinations.Footnote 13 These characteristics make ESCP a rich example of the evolution of a leading business school outside of prestigious American universities.

Second, the study illustrates how French business schools have experienced increased institutional complexity in the higher education system since the second half of the twentieth century.Footnote 14 Like most French business schools, ESCP launched management, leadership, and entrepreneurship studies in the 1960s and 1970s;Footnote 15 from the 1990s onward, it has enhanced its international profile with standards that do not match its historical identity.

Third, ESCP is unique in that it has long held elite status in France, along with HEC Paris and ESSEC.Footnote 16 In 1974, ESCP was the first to launch a course dedicated to entrepreneurship; ESSEC and HEC Paris followed suit in 1976 and 1978, respectively. Since the 1980s, ESCP has offered more disciplines than HEC Paris and ESSEC, particularly in entrepreneurship and management studies.Footnote 17 Finally, ESCP is the first business school in France to have established pioneering training—such as computer coding courses (1968), the Specialized Master’s degree (1986), and the part-time MBA (1993)—and practices that later became widespread in most business schools in France—such as personality interviews during recruitment tests (1970), integration in parallel admission (1970), alternate learning (1995), and the validation of skills acquired experience (2006). Clearly, ESCP is an innovative business school in France.Footnote 18

Data Sources and Analysis

To explore the evolution of a business school’s curricula, I draw on institutional field theories, which depict higher education institutions as working with other organizations—suppliers, consumers, regulatory agencies, and competitorsFootnote 19—within a common institutional framework. The field uses regulations, cognitive belief systems, and normative rules that provide social structure, stability, and meaning to social life.Footnote 20 Following Pettigrew, this case study is longitudinal so that all processes are contextually embedded and revealed through temporal analysis.Footnote 21

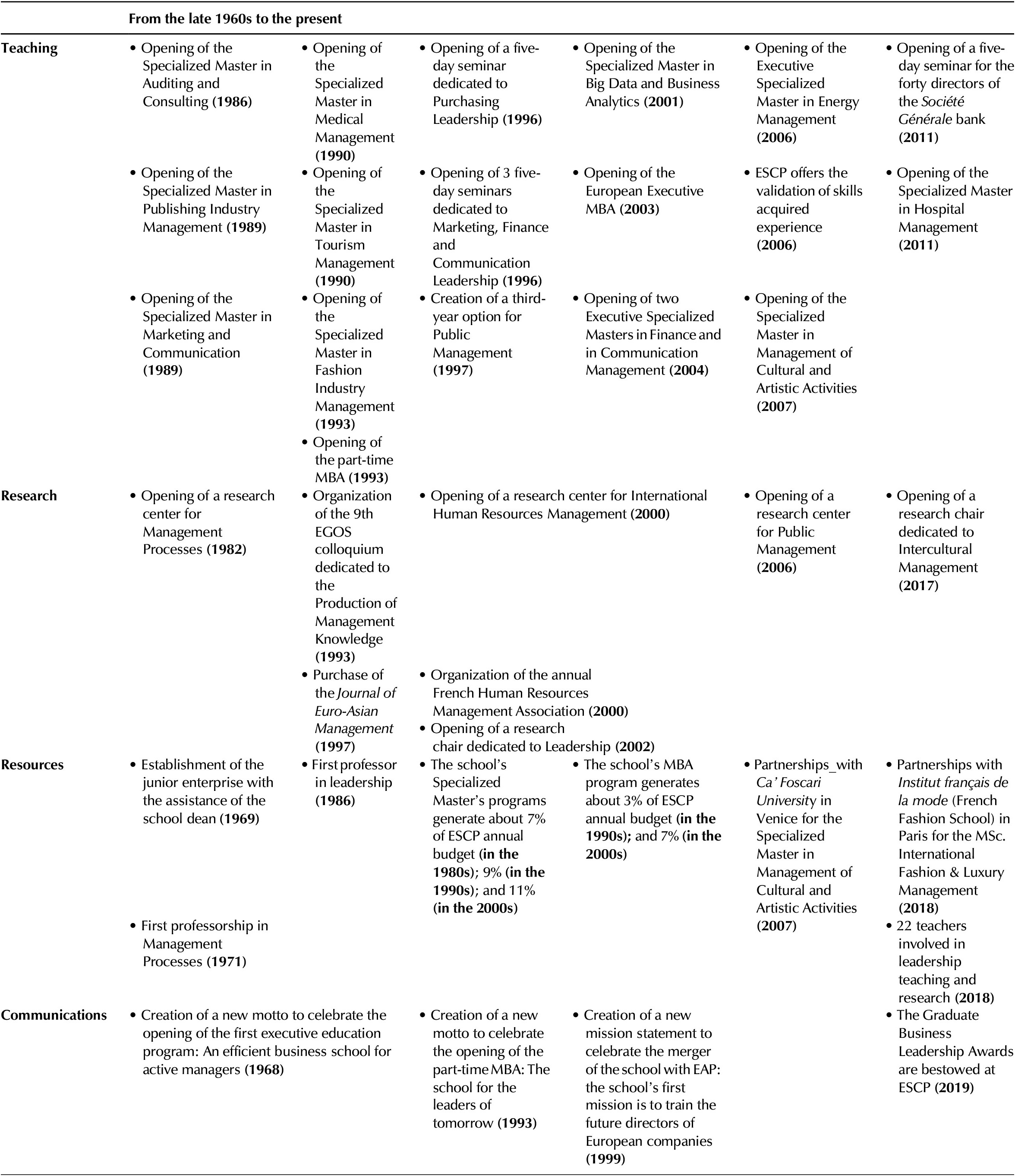

This research adopted a business history approach by analyzing primary sources that were collected from the archives of ESCP, the Paris Departmental Archives, and the PCC. I studied the minutes of meetings held by the administrative commission—the school’s main management body—as well as the training syllabi and self-evaluation reports written for international accreditations. I also collected primary data through interviews with school administrators to investigate the incentives that led to new educational programs. These sources were triangulated with historical monographs and scientific publications written on the history of ESCP. I began my longitudinal analysis by undertaking periodization based on an exhaustive chronology of ESCP training, especially from the late 1960s to the present (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Timeline of ESCP, 1819 to 2019.

Author’s own elaboration.

The article starts in the late 1960s because that is when programs began to diversity.Footnote 22 It then identifies the factors, actors, and processes that initiated the transformations through to the present. My classification of vectors of change is based on previous work that has shown the relevance of specific factors affecting the evolution of business schools’ curricula, such as the needs of the economy, business requirements, and government decisions;Footnote 23 the influence of U.S. business education;Footnote 24 as well as parents’ and students’ expectations and accreditation processes.Footnote 25

I distinguish two specific periods in the history of ESCP. Period 1 (1969–1999) was initiated by governmental decisions that led the school to diversify its training. Period 2 (1999–present) was initiated by the school’s drive toward autonomy and continues from rising pressures related to international rankings, accreditation processes, and competition from other schools. These changes are clear in the school’s development of a wide ranging curricula.

The Evolution of ESCP’s Curricula: From Bookkeeping to Management, Leadership, and Entrepreneurship Studies

This section first provides a brief overview of the context in which ESCP first evolved. The two following subsections present an in-depth analysis of how, beginning in the late 1960s, the school shifted its strategy to train (future) specialist managers, leaders, and entrepreneurs.

French Business Schools: From Secondary Schools Teaching Future Bookkeepers and Businessmen to Higher Education Institutions

Business schools in France were created in the nineteenth century on the model of grandes écoles, especially engineering schools.Footnote 26 However, they were not recognized by the French government as institutions of higher education.Footnote 27 Business schools were considered second-choice options by students who preferred law, medicine, or engineering studies.Footnote 28 Accordingly, the schools taught younger students educational disciplines regarded as useful for companies because public opinion, and sometimes businesses, did not look favorably on managers and entrepreneurs at the time.Footnote 29 Thus, French business schools promoted the roles of bookkeepers and businesspeople.Footnote 30 Consequently, at the end of the nineteenth century, the majority of their graduates worked in accountancy, budgeting, and other financial services.Footnote 31

After World War II, management and leadership started to be perceived as legitimate subjects, and this trend affected business schools’ evolution. In France, a decree passed on December 3, 1947, officially recognized most of the French business schools as institutions of higher education. The French government created the network of Sup de Co (French business schools), in which business schools were subject to common regulations in terms of curricula, recruiting methods, and graduation requirements.Footnote 32 During this time, the United States provided France with significant technical assistance to strengthen its economy.Footnote 33 The United States’ influence in the economic sphere extended to teaching when it sent consultants and teachers to France to spread its vision of management education.Footnote 34

The case of ESCP reflects these historical evolutions. From its creation in 1819 to 1947, ESCP was a secondary school teaching future bookkeepers and businessmen. In 1947 it became an institution of higher education and sought to prepare its students to occupy higher positions in business communities. The new managerial orientation of the school’s training is illustrated in the fact that at the start of the 1960s, ESCP added new subjects—human resources, statistical control, and organizational psychosociology—into its programs.

First Period (1969–1999): ESCP, a Tertiary Business School Teaching Specialist Managers and Leaders

In the late 1960s and 1970s, the number of independently owned businesses in France decreased, while the number of multinational companies increased. Before the 1960s, the French economy leaned on its colonial empire, but after the independence of its last colonies, France turned to its European neighbors, which were emphasizing the importance of a common European market. The Fondation Nationale pour l’Enseignement de la Gestion des Entreprises (National Foundation for Education in Business Administration; FNEGE) opened in France in 1968 to support the introduction of management education, and between 1969 and 1973 it sent approximately three hundred young people to U.S. and Canadian universities to be trained in management. These students returned to France to spread the management education they had learned in North America.Footnote 35

At the end of the 1960s, the director of ESCP,Footnote 36 Jean Vigier—who graduated from the Centre de préparation aux affaires (Business Training Center), which was directly inspired by the Harvard Business SchoolFootnote 37—observed that ESCP’s programs were inadequate to meet companies’ new demands and international competition. Indeed, as he pointed out: “The graduates of ESCP are a perfectly standardized product (same social class, same culture, same aspirations, same training) which constitutes a weakness compared to the current diversity of firms’ demands.”Footnote 38 In spring 1968, Vigier visited seven American business schools—Harvard University, Wharton School of Business, Columbia University, New York University, University of Chicago, Northwestern University, and the University of Michigan–Ann Arbor—to see how first-class U.S. business schools were run and what was included in their teaching programs.Footnote 39 Upon his return, he broadened ESCP’s participant target population in 1969 by negotiating ESCP’s autonomy from the state and the Sup de Co network.Footnote 40 After that, the school organized its own entrance and exit exams. Moreover, as part of the FNEGE program, a few ESCP graduates were sent to the United States in the late 1960s to learn new management teaching methods and practices. In Vigier’s words, the modernization of the school aimed at “putting more emphasis on ‘management techniques’ to promote the preparation of managers and leaders and not bookkeepers.”Footnote 41 From 1969 to 1999, ESCP broadened its student population, resulting in the diversification of its curricula in two ways.

First, gender diversification became a goal for the dean of ESCP. Most grandes écoles were reserved for young men. The situation changed when the École polytechnique—the most prestigious French engineering school—removed gender restrictions in the early 1970s, although different entrance exams were used. At that time, French business schools still imitated engineering schools, particularly the most prestigious ones. This would align ESCP with the best business schools in the world, which already were coed, including Wharton Business School (since 1954), Harvard Business School (since 1963), and INSEAD (since 1967).Footnote 42 Officially, however, coeducation was introduced to respond to the opening up of liberal professions and senior executives in France in the 1970s. Accordingly, ESCP moved to a common entrance exam for both men and women in 1973, with the latter representing 32 percent of the incoming class in 1974 and 45 percent in 1979.

Second, the school developed executive education to meet the expectations of executives needing to update or improve their management knowledge. Vigier noticed that this was heavily taught in U.S. business schools. However, he decided to limit this topic because he wanted to maintain the tradition of grandes écoles teaching young students who had no professional experience rather than established executives. Thus, in 1968, the executive education division included a very small number of students. However, the situation changed rapidly when in 1971 a French law was passed requiring companies with more than ten employees to devote 0.8 percent of their gross payroll to training their workers.Footnote 43 The PCC, owner of ESCP, seized this opportunity to create closer relationships with businesses. The number of people enrolled in executive education rose from about fifty in 1968 to more than seven hundred in 1976, and to more than three thousand in 1999 (Table 1). In the 1990s, the school also created a corporate relations service to form high added-value partnerships with companies to enrich course content and develop studies and research. This tightened the bonds between ESCP and its alumni network, which became the school’s supporters within their companies and contributed financially to the growth of ESCP. Indeed, in 1993, the school launched the first part-time MBA in France. As former dean De-Chantérac-Lamielle (1989–1999) acknowledged, “Delivering an MBA was a vital issue for the visibility of the school abroad. Even if this program was taught in French, the school could pretend to deliver an MBA like all the competing schools.”Footnote 44 A full-time MBA was launched in 2017 to prepare students to be future leaders of international business.

Table 1 Evolutions of the school enrollment and budget, 1969–2019

Author’s elaboration.

Along with adding the curricula for executive education, the school also expanded its specializations of management and leadership studies for initial education (Table 2). In the late 1970s, ESCP joined the Conférence des grandes écoles (CGÉ), which is an association of higher education institutions created in 1973 to promote the influence of its members. The CGÉ is the guarantor of the grande école label, and membership is subject to an evaluation process by current members.Footnote 45 As an accreditation body, the CGÉ is particularly important because it allows grandes écoles to offer Specialized Master’s degrees. These are professional programs in management, targeting applicants who already possess a diploma from a grande école or university, and who want to receive a top-level professional specialization in management. Specialized Master’s degrees are trademarks of the CGÉ. They allow grandes écoles, including ESCP, to teach management students with training traditionally reserved for engineers, biologists, publishers, and political scientists.Footnote 46 In 1986, ESCP became the first business school in France to launch this new Specialized Master’s program in auditing and consulting. It was followed by programs in marketing and communication (1989), tourism management (1990), medical management (1990,) and fashion industry management (1993) (Table 2). The success of these programs led the school to multiply them rapidly; for example, ESCP offered eight Specialized Master’s degrees in 1986 and fourteen in 1998. This growth was imitated by other French business schools.

Table 2 Evolution of ESCP’s curricula in management and leadership education

Author’s own elaboration.

The new leadership curricula were designed to support participants in their personal development. Starting in the 1990s, managers who sought greater career opportunities needed to improve their employability;Footnote 47 earning a degree became a major route to do that. Today, the MBA is the main model, but other specialized training programs also have their place, such as the Executive Specialized Master degree. Moreover, on the French market, credit for both work and life experiences has real commercial value as well as economic and societal utility. That is why, since the turn of the twentieth century, ESCP has offered senior executives an Executive Officer diploma based only on their experience.

In addition to these changes, starting in the late 1960s, ESCP implemented a research policy, created research centers or chairs dedicated to management and leadership, and organized international management colloquiums (Table 2). This diversification was possible because the school acquired new resources, both intangible—with the recruitment of management and leadership professors and the establishment of partnerships with other universities—and tangible —with the creation of financially contributing programs, such as the MBA and the Specialized Masters (Table 2). As a result, the school’s organizational communications have gradually evolved since the late 1960s, highlighting the training of active managers and leaders (Table 2).

This change in the school curricula was also evident in the extracurricular activities of students. After 1969, the school administration encouraged involvement in student associations because this was seen as effective preparation for management jobs. Sports, which were previously optional, became mandatory in the 1970s. The practice of sports was no longer seen as only necessary to prepare male students for military service, which had been true until World War II. Now sports prepared all students to join the elite class by knowing how to fence, golf, ski, or ride horses.Footnote 48 Sports, according to the directors of the time, developed managerial skills. As De-Chantérac-Lamielle wrote: “The practice of sports gives students the physiological means to fight against stress and teaches them team spirit but also competition that should animate their future careers as a manager or leader.”Footnote 49

Second Period (1999–present): Internationalization and Diversification of ESCP’s Curricula in Entrepreneurship Education

From the late 1990s onward, French business schools have been expected to enhance their international profiles in accordance with standards (e.g., international accreditations and rankings, theoretical research published in academic peer-reviewed journals) that do not match the historical identity of grandes écoles.Footnote 50 That is why they transformed their grande école programs into a Master in Management program, as done at the HEC Paris (1999), or a junior MBA program, as at ESSEC (2000). The term “junior MBA” differentiates the ESSEC MBA from the MBAs offered by U.S. business schools: the junior MBA is intended for students younger (18–23 years old) and with less professional experience (between one and two years) than their American counterparts. Grandes écoles have also opened up their students’ recruitment processes, introduced new programs, developed existing ones, and recruited research-oriented faculty members who have more international experience.Footnote 51

In 1999, to increase the school’s international exposure, the PCC merged ESCP with another consular business school, EAP. In 1973 the PCC founded EAP, a multicountry grande école whose mission is to provide an innovative European complement to the other business schools. Since the merger, ESCP has operated campuses in Paris, London, Madrid, Berlin, Turin, and Warsaw. To bring the school closer to the European standard of “bachelor’s-master’s-doctorate” training, ESCP has undertaken several measures. First, in 2003 it transformed its grande école program into a Master in Management. Second, in that same year, the school launched a doctoral program. As former dean Scaringella (1999–2006) acknowledged: “Thanks to the Ph.D., the school has been able to form leading partnerships with foreign universities. This program also allowed it to ‘bypass’ the French universities for the training of future teachers-researchers in management.”Footnote 52 Finally, in 2015 the school launched a bachelor’s degree in management program. Indeed, between 2003 and 2015, ESCP has built a complete portfolio of courses aligned with the European training standard. As stated by the current academic director: “This range of programs is complementary: we train operational leaders through the Bachelor in Management, strategic leaders through the Master in Management and MBA, and specialists through MS [Master] and MSc [Master of Science].”Footnote 53 As a result, the school now educates an increasing number of international managers. As shown in Table 1, the percentage of foreign students enrolled increased from 0.94 percent in 1969 to 53 percent in 2018. The school also made great efforts to transform its name into an internationally known brand, changing its name from ESCP-EAP to ESCP Europe in 2009. In November 2019, ESCP Europe was renamed once again ESCP because including “Europe” was considered too restrictive for the school’s international ambitions.

Moreover, entrepreneurship has become a priority in the European Union. In 2000 the European Union agreed that entrepreneurship should be regarded as a basic skill necessary to increase the EU gross domestic product by 3 percent before 2007, making the economy one of the most competitive knowledge-based economies in the world.Footnote 54 With this change, ESCP moved its curricula toward entrepreneurship education.Footnote 55 It should be noted that until the 1970s, entrepreneurship was not taught at ESCP, and teachers had no apparent interest in how organizations actually came into existence. They focused on preparing their students for careers in well-established companies, whether in the manufacturing, banking, transportation, consumer products, or public sectors. Even so, in 1974 the school administration created an optional management and development of organizations course focused on business creation. This was transformed at the end of the decade into a specialization in its own right, but with mixed results because students wanted to become managers or leaders rather than take on the risks of starting their own businesses.Footnote 56

As shown in Table 3, starting in the 1990s, entrepreneurship training and entrepreneurial resources increased because school management realized that students were unlikely to become managers in the ways envisaged in the 1970s and 1980s. As former dean Scaringella stated:

Because job markets are increasingly precarious, a lot of graduates will not experience the continuity of employment or career profession available to their predecessors. Accordingly, the school should not continue to promote exclusively management or leadership studies. Because students are more likely to manage no one or be managed by another, management and leadership studies should be supplemented with additional programs devoted to entrepreneurship.Footnote 57

Table 3 Evolution of ESCP’s curricula toward entrepreneurship education, 1974 to 2018

Author’s own elaboration.

Accordingly, the Specialized Master Innovation and Entrepreneurship was created (and is still available). With changes in attitudes in the business sector and the academic world toward entrepreneurs, as well as with the economic difficulties caused by the 2008–2009 financial crisis, this trend has accelerated over the past decade. That is why a chair dedicated to entrepreneurship was created in 2007, and two new entrepreneurship options were launched on the Berlin and Madrid campuses in 2017 (Table 3). Finally, in 2018 the school launched another program devoted to entrepreneurship: the Master of Science in Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Innovation (Table 3). So, in a way, students at ESCP became interested in entrepreneurship because traditional career paths—to be hired as a manager or a leader in big companies—had become more difficult.Footnote 58 To support the entrepreneurial orientation of its curriculum and its research policy, ESCP relied on new resources: the recruitment of entrepreneurship professors (whose number grew from one in 1974 to thirty-four in 2011), the opening of an incubator (2003), as well as the establishment of partnerships with engineering schools geared toward entrepreneurship (2006). As a result, the organizational communications of ESCP reflect the growing weight of entrepreneurship in the school: many events have been set up—festivals, awards—while, symbolically, the figure of Jean-Baptiste Say, the neoclassical economist whose work on entrepreneurship is famous, is increasingly associated with ESCP (Table 3).

To sum up, from 1969 to 2019, ESCP diversified its curricula toward specialist management, leadership, and entrepreneurship studies. These changes forced the school to increase the number of permanent professors fifty-two times from 1969 to 2019; during the same period, the school budget increased sixty-eight times, and the school self-financing increased by 140 percent. The self-financing ratio represents the portion of financing requirements that can be met by cash flows from the school’s operating activities. In parallel, the number of students increased seven times (see Table 1). The increase was related to demographics: the number of students as a whole in France increased ninefold between 1960 (310,000 students) and 2018 (2.7 million students). However, there was also a political reason for this situation: the French state pursued a voluntarist policy in the 1960s and 1970s to increase the number of students because, at the time, the development of higher education was considered necessary for economic growth.Footnote 59 Finally, an economic reason must be mentioned here: the increase in the number of students was a response to the growing demands of managers, leaders, and entrepreneurs. Managers represented 4 percent of the working population in France in 1969, 9 percent in 1984, 12 percent in 1993, 14 percent in 2003, and 18 percent in 2018. This continuous increase represents the creation of tens of thousands of jobs per year.Footnote 60 ESCP took advantage of this situation by increasing the numbers of its students and training courses.

Discussion: The Driving Forces behind the Evolution of a Business School’s Curricula

Now that I have unveiled the history of ESCP, it is necessary to discuss in-depth the factors leading to the growth of this business school’s curricula. Six categories of actors and as many processes have been identified, as shown in Figure 2 and analyzed in the following subsections.

Figure 2 Transformation of ESCP’s curricula.

Author’s own elaboration.

Corporate Influence on the School Curricula

My case confirms that French business schools, like ESCP, were connected to certain professional fields and, thus, designed their curricula with the interests of businesspeople in mind. Firm participation in the school curricula is thus reflected in the creation of professionally oriented programs and educational tools (see Figure 2).

ESCP, like other French business schools, created new programs in collaboration with companies. Corporations needed their executives to develop new skills, and executive education could aid corporations to transform themselves by training cross-sections of their managers. This paved the way for the creation of tailor-made programs.Footnote 61 For instance, at the request of the alumni and firms, the administration adapted its curricula. In 1989 ESCP created “year off” internships to allow students to interrupt their schooling for one year to work in a company, and it created special tracks for students with apprenticeship contracts that alternate training with job placements. To guarantee that programs meet both customer requirements and academic standards of the school, company-specific programs select the requests for proposal that are in line with the school’s academic standards. For instance, at ESCP, an academic committee was created in 2008 for the executive MBA program. The participants are the dean, the director of the program, professors in charge of main courses, student representatives, graduate representatives, and contacts at partner firms. The main objective of this committee is to contribute to the evolution of the executive MBA program by adapting its content and design to the expectations of the corporate world and to the new trends in management. Participants systematically fill in evaluations at the end of each session. Once a year, they decide the elective courses list with the professors in charge of the core courses.

Firm participants directly inspired the educational tools. For example, the ESCP’s trading room opened in 1997 thanks to the school’s financial and skills partnership with Reuters, the world leader in real-time information. The objective in creating this life-size trading room was to “allow students to put themselves in the same working conditions as a trader so that they would be more operational the day they enter a real trading room.”Footnote 62

This case study shows that the managerial orientation of the school’s programs is a consequence of the spread of managerialism in every sector of the modern economy. In the nonprofit sector, managerialism has become a by-word for both effectiveness and efficiency.Footnote 63 Thus, one of the core concerns of ESCP is the training of managers at all levels and for both the private and public sectors. In this context, business schools like ESCP must ensure that their pedagogical contents and skill development programs meet the needs of the market and firms.Footnote 64 They also should build political legitimacy by reorienting their missions toward social service. Indeed, business schools face intense political pressures to demonstrate their ability to increase the number of startups, create new employment opportunities, and contribute to firms’ growth and internationalization.Footnote 65

U.S. Influence on School Curricula

My case confirms that, after the World War II, the United States had a significant influence on European business schools as this country was considered the most advanced society in the West.Footnote 66 Since the 1960s, ESCP progressively adopted some international standards (see Figure 2), and more particularly U.S. standards in terms of core values (e.g., the case method, theoretical research published in academic peer-reviewed journals); recruitment faculty (e.g., international professors with doctorates); and program portfolio (e.g., executive programs, full-time and part-time MBA programs).

As noted earlier, at ESCP, the case method and executive programs were launched by Vigier after he visited seven U.S. business schools in 1968, and that he graduated from Centre de préparation aux affaires, which was inspired by Harvard Business School (HBS). Other U.S. standards were introduced by Scaringella, who also studied at HBS in the 1970s, thanks to the FNEGE. These international standards were retained by his successors, many of whom were familiar with the American-style management training, since a former dean (Koch, 2014) obtained his MBA at INSEAD, and the current dean (Bournois, since 2014) completed his MBA at Aston University. In this regard, the ESCP case confirms that, following the Americanization of management education, business schools tend to adopt similar programs, processes, and structures.Footnote 67

Moreover, my findings suggest that for ESCP, the U.S. influence occurred not directly by U.S. foundations but by intermediary French organizations (e.g., FNEGE) or individual actors who were trained in the United States or by American standards, such as the MBA (e.g., Vigier, Scaringella, Koch, and Bournois).Footnote 68 It is significant to note that before the arrival of Scaringella in 1999, ESCP had never been headed by a director holding a management degree. The majority of those who led the school between 1819 and 1999 had degrees in law or economics, or even in history, but not in management.Footnote 69

However, this case confirms previous studies about the limitations of the U.S. influence. Gemelli points out that while America was indeed instrumental, there was also hybridization of and resistance to U.S. methods.Footnote 70 For example, in the 1970s, ESCP adopted some elements of the American model of management education, such as the case method and executive education. It also rejected two main features of the U.S. model: teaching entirely in English, moving into a modern campus (in this case, to the outskirts of the capital) with all the services necessary for teaching, research, sports, and leisure. Gemelli also points out that some elements of the U.S. model were adopted but in the local context. This refers particularly to the school’s first MBA, which was launched in 1993 as a part-time program. Compared with U.S. standards, it had a shorter timeframe (that is, one year), students had less professional experience (between one and two years), and more than 80 percent of classes were taught in French.Footnote 71 Therefore, this MBA was not a simple duplication of the American MBA, but a French MBA adapted to its environment. This example illustrates the selective appropriations of American methods rather than a process of mechanical imitation. Indeed, at ESCP, the MBA has not become the flagship product of the school; rather, that remains the Master in Management. In 2018, the latter represented 3,074 students out of 5,573 (55 percent) and almost 800 graduates out of 2,100 (38 percent).

My findings confirm that, given the difference in scale, available resources, and cultural environment, the U.S. influence did not lead to an undisputed predominance of the university-based graduate business school model.Footnote 72 The ESCP, like most business schools worldwide, responded to the forces of globalization,Footnote 73 and not exclusively to U.S. standards. ESCP did so by (1) merging with national competitors (e.g., with EAP in 1999); (2) by investing in campus locations in foreign countries (e.g., in London and Turin in 2004; in Warsaw in 2015); and (3) by forging partnerships with foreign business schools (e.g., with HEC Montréal in 2018). At ESCP, Americanization did not result in a “carbon copy” transfer. Empirically, and following Gemelli, I find the concept of Americanization should be replaced by that of hybridization, which implies a process of translation from one context to another, not a mechanical transfer.Footnote 74

The European Influence on the School Curricula

With the independence of the last French colonies in the 1960s, the French economy looked to its neighboring countries, which emphasized the importance of a common European market. At the same time, the growth of Europe as a major economic bloc (customs duties in the Common Market were abolished in 1968) created a demand for people trained in management with an understanding of languages and countries other than their own. The euphoria following the establishment of the Single European Market in 1992 boosted the need for cross-border managers and intensified demands for linguistic and cultural training.Footnote 75 Similarly, in 1998, the Bologna process initiated a movement to bring European higher education institutions closer to the bachelor’s-master’s-doctorate standard (see Figure 2). This resulted in the standardization of the educational system at European universities and the harmonization of study in terms of curricula, syllabi, and course credits.

ESCP gradually incorporated this Europeanization; for example, it introduced the study of European regulations into the school curriculum for accounting and law as early as the 1970s. In the early 1980s, it created finance and marketing courses related to the European market. In 1989 ESCP divided its school year into semesters rather than terms to make the school compatible with partner universities in Europe. It increased the number of its European partner universities from approximately ten in the 1970s to around twenty in the 1980s and to roughly thirty in the 1990s. A powerful event for ESCP was the fall of the iron curtain in the early 1990s, and it took advantage of the opening up of the former countries of the communist bloc to offer management training adapted to the specifics of these former socialist countries.Footnote 76 Following the Bologna process, ESCP implemented a doctoral program in 2003 and a bachelor program in 2015. This led ESCP to develop, alongside its French Specialized Masters, more European master’s programs, such as the Master of Science for Executive Education. This made the school portfolio’s not only readable but also comparable across the continent. ESCP continued to evolve its training to meet European expectations. It realized that management education could attract non-French students, which is why it remodeled its grande école program as a Master in Management in 2003, created a European seminar in 2009, and opened new campuses in London, Turin, and Warsaw. Other Elite European business schools like ESCP—INSEAD, London Business School, International Institute for Management Development, and HEC Paris—now also offer approaches to global management education that respect European traditions, such as action learning, practice engaged research, customized executive education, and a focus on international activities.Footnote 77

The ESCP case study confirms that the Europeanization of higher education created institutional pressure on business schools.Footnote 78 In this sense, my work somewhat agrees with Kaplan, who found that the Europeanization of business schools started in the late 1990s with the EQUIS accreditation, which enabled the “(re) emancipation from the domination of U.S.-style business schools.”Footnote 79 However, my study shows that Europeanization was accomplished much earlier—in the 1970s. ESCP, because of its cultural and geographical proximity to the European market, counterbalanced the influence of the American model with the specificities of its market. European authorities also encouraged certain teaching disciplines. For instance, numerous official EU documents called for both fostering an entrepreneurial spirit among its citizens and for creating business and economic growth.Footnote 80 Therefore, ESCP, like many business schools, increased the number of its entrepreneurship programs. The case of ESCP confirms that the Europeanization of business education was not a passing fashion but a logical response to growing competitiveness in France and Europe.Footnote 81 This economic argument must be supplemented by a cultural one. Indeed, Kaplan shows that the Europeanization of business schools in Europe was both an economic response to the construction in Europe in the second half of the twentieth century and the translation of a cultural singularity that business schools on the continent have expressed since the nineteenth century.Footnote 82 As Kaplan points out, European business schools have historical peculiarities compared with their counterparts in the United States, such that, since the nineteenth century, European management has taken a cross-cultural, societal management approach based on interdisciplinary principles. These particularities are illustrated in the case of ESCP, as Kaplan notes: the school’s curriculum is based on cross-cultural education (e.g., students of all programs pursue their studies in a minimum of two countries); the school requires meeting societal objectives (e.g., professors are asked to integrate these into each of their courses); and the school promotes interdisciplinarity. It accomplishes that last through its humanities and liberal arts programs while encouraging double degrees with partner universities specialized in areas other than management.Footnote 83

National Financial Pressure

Since the late 1960s, ESCP’s financial needs have dramatically increased, including to build a permanent faculty body; to carry out international research; and to create language laboratories, printing services, computer rooms, digital libraries, and business incubators. Meanwhile, the PCC’s monetary contributions to ESCP have gradually decreased. The latter accounted for 75 percent of the school’s budget in 1960, 35 percent in 1996, and only 11 percent in 2018. According to Dean Bournois, the PCC’s contribution will represent 0 percent of the school’s budget in 2022.Footnote 84

That is why ESCP created customized programs that financially contribute to its budget (see Figure 2), such as the customized programs for enterprises. The school also has created more than fifteen chairs since 2003. Each chair receives funding from companies, ranging from a few hundred thousand to a few million euros, and each chair is held by a professor who guides the department’s objectives and follows guidelines for creating new courses. For example, the Deloitte chair, created in 2018, is dedicated to circular economy and sustainable business models. It culminated in the launch of a course in circular economy taught in the Master in Management, in the International Sustainability Management MSc, in the executive MBA, and in several different MSc programs.Footnote 85 To date, all programs—except the Master in Management—cover all their own production costs plus generate a profit that contributes to the school’s general overhead. Bournois says that in the near future, ESCP should launch a Doctorate in Business Administration to diversify its sources of revenue and increase its competitiveness.Footnote 86

Indeed, the ESCP case study confirms previous research that financial pressures influence business schools’ curricula.Footnote 87 It follows a generalization of the findings of Hommel and Thomas: French consular business schools, like business schools embedded in public universities, are facing trickle-down effects resulting from fiscally constrained governments deregulating higher education systems.Footnote 88 First, this situation results in the switch from subsidized to tuition-fee-based management education. ESCP has multiplied its resources by accepting donations, creating programs that contribute financially, signing various research contracts with private firms, and increasing tuition fees. Second, this situation leads to greater prioritization of entrepreneurial initiatives, like the establishment of new chairs funded by private firms.

ESCP is also a reminder that financial pressures do not necessarily imply the wholesale remodeling of school curricula. Other funding solutions have been found, but they do not affect the school curricula. For example, in 2005, the ESCP Alumni Association launched a foundation and conducted fundraising campaigns. From 1960 to 2018, like other French business schools, ESCP has dramatically increased its tuition fees. Over that period, ESCP increased them fivefold, and in 2018 tuition fees represented 75 percent of the school’s budget.Footnote 89 Finally, in 2014, the French government created a new legal status for ESCP and some other Établissement d’enseignement supérieur consulaire (French consular schools), which encourages private investors to buy shares in business schools to make them completely self-financed. This status confers on the consular schools a legal personality and an operating flexibility like that of public limited companies, although they are nonprofit organizations. As a result, the schools can use programs’ earnings and fundraising to pursue their educational plans.

Accreditation and Ranking Pressures

This case also demonstrates how the spread of accreditation and ranking processes influenced the pedagogical design and quality of courses.Footnote 90 Indeed, the quest for accreditation forced ESCP to redesign its programs to be more integrated. For instance, in 2002, there were six programs in the ESCP MBA portfolio: the full-time MBA in Paris, the Executive MBA in Paris with a Casablanca track, the Executive MBA in Madrid, the Central European MBA in Berlin, and the Global MBA operated in partnership with Purdue University in America. These programs were developed between ESCP and EAP. However, they varied greatly in nature and size, and were small in terms of enrollment. This was a problem because these MBA programs ranked poorly compared with international benchmarks, and thus it was a priority to overhaul this portfolio. In 2003, the European Executive MBA was launched with the same curriculum as the Paris Executive MBA, but it was delivered in English. The Madrid Executive MBA and the Casablanca track were eventually ended, and ESCP withdrew from the Global MBA. In 2006, the school combined the Paris Executive MBA, the European Executive MBA, and the full-time MBA into a single program with different core course tracks offered in Paris, London, and Turin. The school’s Executive MBA progressed from thirty-seventh place in 2005 to twenty-second in October 2007 in the Financial Times; in 2017, it ranked in the tenth spot.

Accreditation and ranking processes also influenced increased management research in the ESCP agenda (see Figure 2). Before the 1990s, ESCP did not take rankings and accreditations seriously. When the latter became a sign of program quality for prospective students, corporate recruiters, and other stakeholders,Footnote 91 ESCP moved to become a more research-based school and to produce its own knowledge specifically for management practitioners.Footnote 92 This trend is true for all business schools because “research provides a direct competitive advantage in supplying leading-edge content for the faculty to dispense. It also works indirectly as a way of attracting outstanding people and maintaining the brand.”Footnote 93 As a result, a criterion for hiring and promoting management professors is publication in academic journals.Footnote 94 However, the growing importance of research in teachers’ agendas as well as the associated financial costs are controversial.Footnote 95

My case also reveals the administrators of business schools have a challenge to not only to be part of the labeling process of the accreditation agencies but also to be included in the evaluation processes of competitive business schools. For instance, in 2008, for the first time, a former ESCP dean—Morand (2006–2012)—was part of the peer review team of European Foundation for Management Development for the attribution of the label EQUIS for another French business school.Footnote 96 This allowed ESCP to contribute to the development of standards in its market. Because of this, ESCP is now an active player in the accreditation process. My case, following McKiernan and Wilson, shows that ESCP deans understood that its rankings and accreditations would lead to its elite status internationally.Footnote 97 They did this in a manner that preserved its status as a grande école. That is why, even though ESCP is accredited and ranked among the best business schools in the world, it will not replace its status of a French grande école with the globalized status of an international “business school.” It should be noted that grandes écoles are not the opposite of international business schools, as Kadeih and Greenwood claim, but that they are complementary.Footnote 98

Competitors’ Influence

Since the end of the 1960s, ESCP has faced a tougher academic environment. Some U.S. business schools have internationalized and new competitors have sprung up in Europe, particularly Business Administration Institutes and management faculties in France. Additionally, engineering schools became serious competitors to business schools,Footnote 99 and institutes for political studies started to train future leaders of the public and private sectors. Now, e-learning programs compete directly with in-person business schools for executive education. In terms of training, these e-programs can respond flexibly, and generally at a lower cost, to the changing expectations of companies. Executive education competition is also fierce from programs run in-house by human resource teams and by consultancies; and, of course, from other European business schools, including HEC Paris, ESSEC, London Business School, ESADE, and Instituto de Empresa.

ESCP needed to distinguish itself nationally and internationally from all of these competitors, and it did so by creating differentiated programs (see Figure 2). As noted above, in 1993, ESCP created the first part-time MBA in France, and in 2018, it launched the first academic training in Europe to address LGBT+ specific issues. Most competing schools also started to distinguish their programs beginning in the 2000s. ESSEC in Paris launched a “global MBA with a major in luxury brand management” to profit from Paris’ famous fashion industry, and its business school in Marseille launched an Executive Maritime MBA to enhance its port establishment. Likewise, Toulouse Business School launched an Aerospace MBA in 2000 and a Specialized Master in Air Transport Management in 2002 because of its proximity to the established airline industry in the region. Therefore, despite a high similarity among French business schools’ curricula, some regional divergence remains.Footnote 100

This case study confirms that competition does not exclude cooperation. French business schools work together to recruit the brightest students; for example, in 1990, ESCP, HEC Paris, and ESSEC created a common exam system that is still used today.Footnote 101 ESCP also worked with foreign business schools to launch joint programs; in 2018, it signed an agreement with HEC Montréal to allow students from the two institutions to earn a dual master’s degree.

In summary, the curricula of a business school like ESCP does not evolve in a vacuum; rather, it occurs through numerous influences. For example, the trend of including management, leadership, and entrepreneurship in school training is based on key internal and external factors, actors, and processes, and the latter are closely linked and reinforce each other. Financial pressures created the need for corporate relationships so business schools can generate income. Across Europe, national evaluation systems have linked academic performances of educational institutions to percentages of public funding, and the increasing costs of rankings and lowered amounts of public funding have bolstered these relationships.Footnote 102

Conclusion

This article makes an empirical contribution to understanding the institutional development of European business schools. In the case of ESCP, the lack of legitimacy in the nineteenth century led it to focus on teaching occupations that were important economically and socially, so it concentrated on educating younger pupils to be bookkeepers or generalist or specialized businessmen. However, starting in 1969, ESCP diversified its teaching portfolio to include leaders, managers, and entrepreneurs. This occurred because these three groups were more and more considered the driving forces of economic growth.

This article also contributes to business history by showing how the expectations of the wider society and the internal constraints of ESCP (e.g., state supervision, budgetary contributions from the PCC) influenced what it taught, and it shows what caused ESCP’s curricula to evolve from the late 1960s to the present. More precisely, it suggests that six factors (see Figure 2) provoked changes in its human and structural resources and in its teaching and research curricula. These elements contributed to the transformation of ESCP, which evolved from a vocational school—that is, preparing students for specific trades related to business and accounting—to a ranked professional school—that is, helping students develop the skills and acumen transferable to any type of organization. Internal changes included hiring more experienced professors and connecting with alumni, and external forces included building relationships with corporations and private foundations, and working with accreditation agents or press bodies. There is no sharp distinction between these external and internal forces. For instance, the school deans (internal actors) participate in evaluation committees within accreditation agencies (external actors). Moreover, external forces do not necessarily directly affect the school’s curricula: intermediate actors might be necessary. For instance, in the 1970s the FNEGE offered U.S. foundations and business schools the chance to influence decisions made at ESCP.

Finally, like Pettigrew, my findings confirm that global trends and political, economic, cultural, and institutional pressures at the level of nation-states led to the convergence of European business schools, which nonetheless maintain their own diverse local patterns.Footnote 103 Similar to Gemelli, this study finds how, in the face of the Americanization of management education in the second part of the twentieth century, ESCP chose selective imitation; that is, it translated American patterns into its own institutional grande école culture.Footnote 104 Its curricula adapted only certain American influences while it rejected others in order to maintain its national characteristics. ESCP does not aim to replace its French status of grande école with the globalized status of international business school because, and as pointed out above, the two logics are complementary.

This article provides exciting new directions for the study of business schools. First, the organization of curricula vary depending on factors such as institutional traditions, academic culture, and internal resources.Footnote 105 Thus, more comparative and longitudinal research examining the variety of training within business schools is needed. It would be interesting to research the development of business schools in particular countries that, like Germany, have resisted foreign models.Footnote 106 It would be equally important to study countries that were previously colonized by Western powers and which, after independence, drew inspiration from foreign models or developed their own models. Second, future research should carry out large sample studies to identify similar or different patterns of development for business schools’ curricula. It would be worthwhile to study the modes of operation of business schools developed outside the West, in contexts where prevailing socioeconomic paradigms differ from those in Europe or North America. The case of business schools in China, which were opened in an ideological climate strongly imbued with communism but are now starting to seek Western accreditations such as EQUIS, AACSB and AMBA, would be a significant subject of in-depth research. The internationalization of the curricula of business schools in the West is based on more than just American and European influences.Footnote 107 Third, research is needed on how certain religions or philosophies—such as Confucianism, Buddhism, and Islam—as well as certain Asian authors—such as Sun Tzu—have impacted the teachings of business schools in the West.Footnote 108 These influences are insufficiently known, particularly regarding their characteristics, actors, and evolution. Therefore, I suggest studying more precisely how non-Western factors are embodied in the curricula of Western business schools, which actors are involved, and whether and how these influences affect the transplantation, adaptation, or resistance phenomena.