“ZIK OF AFRICA”: AN ASSASSINATION ATTEMPT?

Into the unknown, let me go, having served the will of my maker. But I go full of supreme confidence and spiritual satisfaction that I have served my Mother Africa to the limit of my physical ability—and even gave my most [prized] possession—my life—for the redemption of Africa.

———Nnamdi Azikiwe, 13 July 1945On 13 July 1945, the managing editor of West African Pilot gave the paper's founder and proprietor, and arguably the most famous political journalist in West Africa in that era, Nnamdi Azikiwe, a message the newspaper's wireless operator had intercepted earlier that day. It reads, in part: “first item … assassination of the two most important persons … xxx already started on steps towards … but proposed assassination will take place before … targeters [sic] are detailed watch cinema halls and dancing halls xxx arranging get round people beg ‘A’ give lecture where all possibility assassination can take place in hall…” (Azikiwe Reference Azikiwe1945).

The assassination was allegedly planned for between that day and 16 July. This was the time of an on-going industrial action by the African Civil Servants Technical Workers Union that was demanding an increase in the living allowances of workers, which the colonial government had rejected. Azikiwe was convinced that this was a plot to get rid of him by a government rattled by the industrial action and piqued by the vigorous support he and the West African Pilot had given the striking workers. The Pilot was perhaps the most famous and most strident anti-colonial newspaper in the west coast of Africa in the era just after World War II, and Zik was considered the “number one” enemy of the colonial government. One former colonial officer in Nigeria, Harold Smith, later described Zik as “Britain's bête noire,” because he had “poured forth his hatred of the colonial regime for a decade through the pages of his West African Pilot” (Reference Smith1993).

“In the light of these [threats], and considering the circumstances under which the wireless message was handed to me, naturally I became apprehensive of my safety,” Azikiwe said in his publicly statement released at the end of the controversy. “Shocked and terrified” by the assassination plot, he fled Lagos “as a fugitive from unknown assassins” to the east of the Niger River from “whence I came.” Yet, he left Lagos convinced that if he was killed he would die with “supreme confidence and spiritual satisfaction that I have served my Mother Africa” and, thus, die in the pursuit of “the redemption of Africa.”Footnote 1

Before he left Lagos, Azikiwe sent an omnibus cablegram to prominent people and organizations in the United Kingdom. A Nigerian resident in London who received this organized the National Committee of Africans to mobilize world opinion to prevent Azikiwe being murdered. The Committee sent cables to key people around the world such as Truman, Stalin, and de Gaulle, to organizations including the Indian National Congress, and to Pravda and newspapers in the United States and the West Indies (Coleman Reference Coleman1958: 285–86). Even though the Public Relations Office of the British colonial government and a few other newspapers critical of Azikiwe dismissed the assassination plot as a ruse, public life and politics in Nigeria were dominated for several months by the political crisis the story triggered. It also turned Azikiwe into a national hero among the masses (ibid.: 286).

This incident was one of many examples of Nnamdi Azikiwe's significance in colonial and postcolonial Nigeria. At different times he became a dominant figure in the Nigerian media and eventually in Nigeria's political landscape. Real or supposed threats to Azikiwe's life, rumors of his death, and eventually his actual death were major political and social events. They not only dominated the national discourse but were also used to determine and define where people stood on the questions of Nigeria's political freedom, independence, national unity, ethnic amity, and ideological struggles within and beyond Nigeria. Important here is that Azikiwe's long political and intellectual life was constructed around the emancipation of what he must have imagined as global Africa: Africa and its Diaspora. His concern with and intellectual exertions about Africa, captured in the emergent “New Africa” philosophyFootnote 2 and later articulated in his book Renascent Africa, as well as his “cultural kinship” with literary figuresFootnote 3 and thinkers in the black world, led to the affectionate epithet, “Zik of Africa.” Yet, Zik of Africa was also a man who embraced the temporal and spatial specificities that produced and defined him. As evidenced by his traditional title of Owelle of Onitsha (Onitsha being his hometown in southeastern Nigeria), Zik's expansive cosmopolitan vision never excluded his immersion in and celebration of the culture and ethno-nationalist realities in which he lived. However, while his forceful commitment to the emancipation of black people, specifically Nigerians, was never in doubt, he was at the same time vulnerable to accusations of holding strong, exclusionary, and therefore discordant loyalty to his Igbo ethnic background.Footnote 4 Zik articulated racial and continental emancipation and national unity through some of the most rousing rhetoric in Nigeria's political history, particularly in the late colonial era. And yet, the man who described himself as “the beautiful bride of Nigerian politics”Footnote 5 could at times be so protean in his positions and alliances that his allies and adversaries alike sometimes questioned his ideological consistency. For example, in 1983 he contemplated leading his Second Republic political party, the Nigerian People's Party (NPP), into alliance with the ruling National Party of Nigeria (NPN), an alliance from which the party had previously withdrawn to join the opposition coalition. President Shehu Shagari mocked him at a campaign event in the former capital of Zik's home region of Enugu as not the “beautiful bride of Nigerian politics,” but rather a politically promiscuous prostitute.Footnote 6

Indeed, during most of his active public life Nnamdi Azikiwe thrived in crisis. Personal, financial, and political crises that might have ended the careers or even lives of some leaders instead brought him more prominence, popularity, and respect, and greater centrality in black Africa's (particularly Nigerian) political history. As one of Africa's most famous anti-colonial activists, thinkers, journalists, and political leaders, whose ideas influenced the likes of young Julius Nyerere, Kwame Nkrumah, and Nelson Mandela,Footnote 7 Azikiwe's actions and inactions, whether by design or by fate, attracted controversy. As a person, Zik was urbane and amiable, yet he wielded one of the most acidic pens in African journalistic history.Footnote 8 Whether on the soapbox or in articles and editorials, he was as inspiring to his admirers as he was brutal to his adversaries. We shall see that, even in death, Azikiwe still sparked controversies.

In many ways, Zik's biography mirrors not only Nigeria's history but also the twentieth-century struggle for global black emancipation. He bestrode twentieth-century Nigeria like a colossus, as is apparent from the large body of work on his life and times (e.g., Echeruo Reference Echeruo1974; Dudley Reference Dudley and Otite1978; Nwankwo Reference Nwankwo1996; Tonkin Reference Tonkin, Barber and de Moraes1990; Flint Reference Flint1999; Newell Reference Newell2016; Nwakanma Reference Nwakanma2017; Coates Reference Coates2018). A New York Times obituary observed that Zik “towered over the affairs of Africa's most populous nation, attaining the rare status of a truly national hero who came to be admired across the regional and ethnic lines dividing his country.”Footnote 9 And as John E. Flint correctly argues, “In many respects Azikiwe represents an archetype of the African nationalist leader and was an important pioneer of African nationalist movements” (Reference Flint1999: 143–44). Zik's biography in some ways epitomizes the anti-imperial struggle in the black world.

This is why in his death a vital part of Nigeria's history was at stake, a fact that virtually everyone involved in burying “Zik of Africa” recognized all too well. In light of this, here I will use Azikiwe's death and burial to scrutinize how and why the deaths and burials of prominent persons in Africa are often occasions for cultural crisis.

I will explore how the perspective of cultural crisis can help us account for the death, in 1996, of Rt. Hon. (Dr.) Nnamdi Azikiwe, Nigeria's first and only ceremonial president. As Katherine Verdery famously alerted us to, “Dead bodies animate the study of politics” (Reference Verdery1999: 23). My account here will highlight the different dimensions of the cultural struggles to appropriate his legacy, both material and symbolic, by his family and clan, traditional authorities, his ethnic constituents, the military regime in power, politicians and the political class, as well as other powerful interests in Nigeria.

I employ “retrospective ethnography” based on my initial engagement with this subject matter as a journalist in the mid-1990s Nigeria. In using this method I follow Almeida (Reference Almeida2007; Reference Almeida2009), but unlike Ferreira and De Almeida (Reference Ferreira and Vespeira de Almeida2017), I am not as concerned with “how past time is experienced by the ethnographic subjects, in a process that is fundamentally marked by the coexistence of different, and necessarily mutating, temporalities” (Almeida and Ferreira Reference Almeida and Ferreira2015), as I am with how the ethnographer recovers past participant observation as a lay ethnographer (in this case as a journalist) in the present analysis of a past event. In the period of Zik's death and burial, I interviewed many people and witnessed some of the events I will describe. I mobilize these initial, journalistic participant observations (during which time I could not publish all that I witnessed and discovered) and, now as a trained ethnographer, explore their implications. I also draw upon a life story method and my research in public archives. I see continuities between my close reporting of Zik's death and burial and my research a few years later as a student of death and burial in Africa.

Scholars have suggested that journalism and ethnography share some affinity (Grindal and Rhodes Reference Grindal and Rhodes1987). In this context, Walt Harrington argued that journalists are “the junkyard dogs of ethnography” (Reference Harrington2003: 90; cf. Hannerz Reference Hannerz2002; see also Jackson Reference Jackson2008). Grindal and Rhodes add that journalists and ethnographers “intrude into the lives of others and report what they find to a reading public” (Reference Grindal and Rhodes1987: 11).Footnote 10 Ståhlberg, who was a journalist before becoming an anthropologist, concludes that both are “experts in cultural representation and interpretation” (Reference Ståhlberg2006: 49). However, the transition from the process of initial reporting to analysis “through a retrospective conversion of … learning, remembering and note-taking … into [a] pretext for something else” (Ingold Reference Ingold2014: 386) that I undertake here represents a shift from reportage to engagement (see ibid.: 392).

Two caveats are needed. First, the recent literature on the politics of the dead (body) in Africa is fascinating (see Bernault Reference Bernault2006; Reference Bernault2010; Reference Bernault2013; Reference Bernault2015; Posel and Gupta Reference Posel and Gupta2009; Fontein Reference Fontein2010; Reference Fontein and Stepputat2014; Reference Fontein and Robben2018; Fontein and Harries Reference Fontein and Harries2013; Lamont Reference Lamont, Jindra and Noret2011; Stepputat Reference Stepputat and Stepputat2014), and in this article, I refer to aspects of the importance of the corporeality of the dead body (human remains, the corpse/cadaver). However, I will concentrate on the politics of death, in general, not the specific politics of the dead body, or “bones, bodies and human remains,” as Fontein describes the politics of corporeality (Reference Fontein and Robben2018: 337). What Fontein calls the “emotive materials of human corporeality” (Reference Fontein and Stepputat2014: 128) is useful here in that the cadaver is a crucial component of the process of burial, commemoration, and memorial. My focus, though, is the “affective presence of the dead,” as not only a spirit but also an enduring political exemplar and body-history, a body that encompasses and signals “history,” in this case, cultural, ethno-nationalist, and continental “history.”

The second caveat is that I have deliberately written this article in a non-chronological way, including by using the literary technique of flashback. I do so partly because there are different starting points from which the subject's life is encountered and narrated in both lay and scholarly literature. Also, tacking back and forth in this manner usefully disrupts chronological accounts of Zik's life that dominate the extant literature.

DEATH AND (CULTURAL) CRISIS

I want to suggest that the death, and consequently the burial of prominent persons, in contemporary Africa represent occasions for the (re)production as well as the management of crises that are cultural—familial, political, socio-economic, legal, gendered, and so forth. Further, the (re)production and management of cultural crises present different kinds of opportunities for, or obstacles to, those who have an interest in gaining, in one way or another, from the person's death and burial. While recent literature considers diverse forms of crises (re)produced by death and burial (Stamp Reference Stamp1991; Cohen and Odhiambo Reference Cohen and Odhiambo1992; Reference Cohen and Odhiambo2004; Gordon Reference Gordon1995; Adebanwi Reference Adebanwi2008a; Reference Adebanwi2008b; Branch Reference Branch2010), most scholars studying Africa focus on distinctive challenges presented by specific cases of deaths and burials (and related memorials) of significant persons (in terms of the burial site, inheritance, conjugal or kinship rights/rites, legal authority, succession, etc.). Consequently, they either understate or overlook the generalizability of the “essential contestability”Footnote 11 of the material and immaterial relations of the past, present, and future provoked by death—particularly as these relations are disturbed or challenged by the person's absence—and by the process of their burial or reburial.Footnote 12

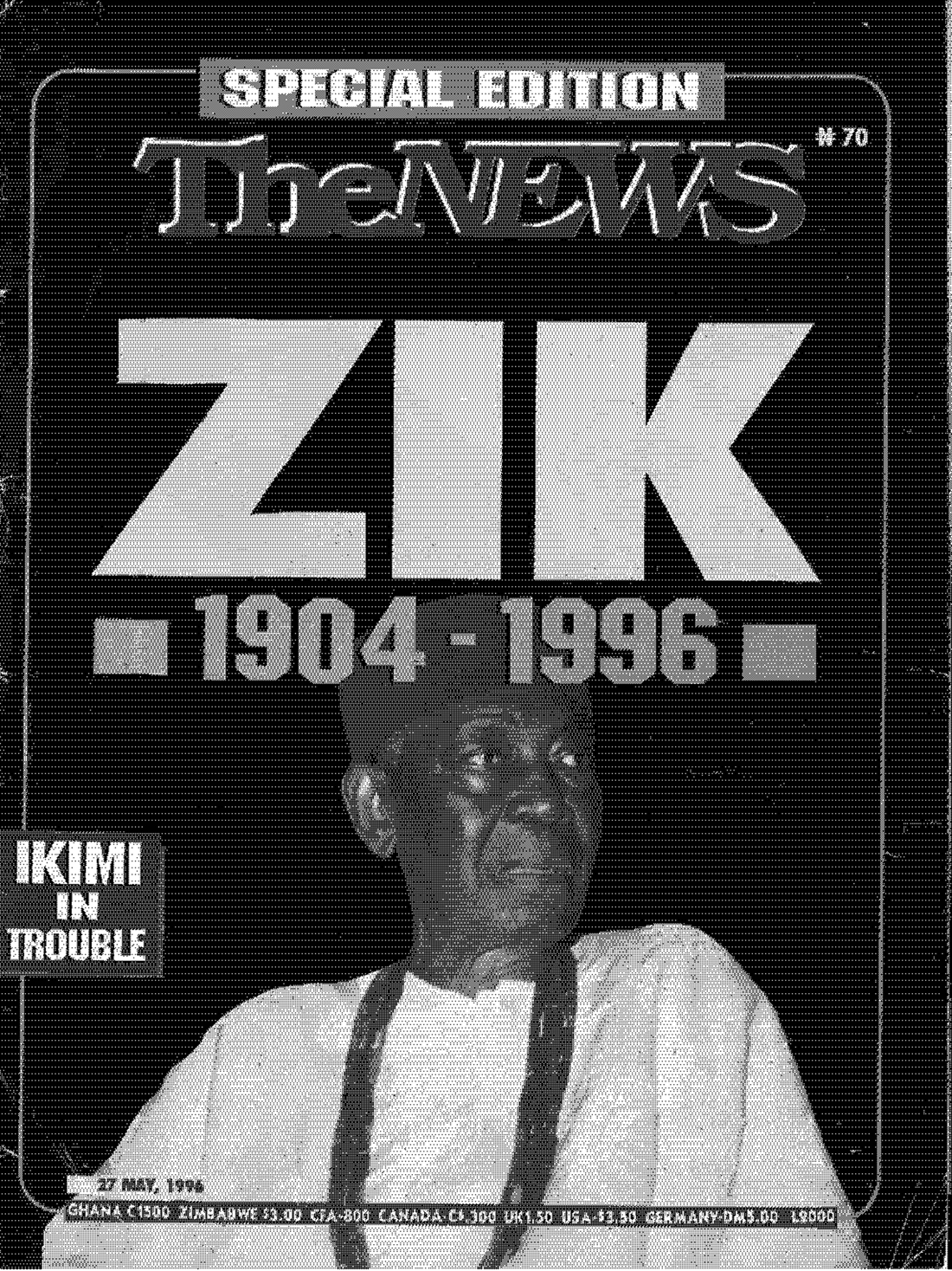

Image 1. The cover of TheNEWS magazine (reproduced with permission).

However, recent literature has highlighted more useful ways of understanding death and burial in modern, urban Africa, against the backdrop of the older anthropological literature on “traditional” (African) societies (Malinowski Reference Malinowski1948; Van Gennep Reference Van Gennep, Vizedom and Caffee1960; Goody Reference Goody1962). In that older literature it was argued that “death introduces physical, spiritual, and social rupture,” which is healed in order to ensure “the renewal and continuity of life,” through “transitions … that often serve simultaneously to guide the deceased and the living safely into a beneficial and life-giving balance with each other” (Lee and Vaughan Reference Lee and Vaughan2008: 344).Footnote 13

Yet, the study of the death and burial of prominent persons in modern Africa must be more attentive to crisis (not merely “social rupture”) as an important pathway for analyzing the manifold challenges raised by the absence and the “posthumous careers” of such persons. The foci of Cohen and Adhiambo's two important books on this subject—“the politics of knowledge” and “the sociology of power” (Reference Cohen and Odhiambo1992), and “the production of knowledge and claims of truth” (Reference Cohen and Odhiambo2004)—are reflections of politico-cultural (including legal) crises in which the particular deaths of two Kenyans, S. M. Otieno and Robert Ouko (who was murdered), provide contexts for examining how death, in general, presents opportunities for, or obstacles to, posthumous gains by people directly or indirectly related to the dead.

By gains, I mean attaining something or ensuring that something happens to oneself or others as a consequence of the death, be it material (such as wealth, property, or position) or immaterial (vengeance or retribution, status, cultural authority or priority, punishment, legal rights, or judicial or extrajudicial change). In this way, the death of a significant person transcends personal loss, even for their immediate family. Thus, a crisis is produced not merely by death but also by the intentional actions of those related to the deceased and those who hope to gain, or fear they might lose, something as a consequence of the death and/or the burial process.

Crisis, in the sense that I use it here, is, to paraphrase Evert van Der Zweerde, “the possibility of real conflict by virtue of the fact that there is an element of decision[-making]” at stake in death and burial (Reference van der Zweerde2007: 151). This includes deciding who is entitled to make decisions in respect of the dead and the affairs of the dead, and also regarding their burial or reburial. The crisis is prompted by the essential contestability of the past, present, and future of the dead, including their legacy or significance, or the meaning of their life. My approach here ties back to the tradition established by Freud's contribution to the study of society in relation to the “ineluctable fact of death” (Goody Reference Goody1962: 30) and the role of death in society. In a departure from the “rationalistic positivism” of the English intellectualists such as Tylor and Frazer, and the sociological approach of Durkheim and the French School, who concentrated on the integrative aspects of the group goals and interests, Freud focused instead on “the conflict situations inherent in any personality system” (ibid.). Freud found conflict inevitable under existing psychical and social conditions.

I use cultural crisis to label a breakdown in or interruption of existing modes, priorities, and processes for the management of temporal and spatial human social relations (including interpersonal, marital, kinship, gender, communal, local, or national ones), of affairs, property, and ownership (and therefore inheritance, both material and symbolic), and of reputation (and its benefits and drawbacks in a particular social context). Thus, a cultural crisis presents opportunities for (re)appropriating things, making claims, enhancing or destabilizing existing statuses, settling scores, and “righting” wrongs. Such wrongs may have resulted from the agency, actions, or subjectivity of the deceased, or from things they represented materially or symbolically, or from things done for or to them while they were alive. The crisis also presents an occasion for settling between different and sometime conflicting accounts of what the dead person's life represented and continues to represent.

However, the struggles to gain symbolically and materially from the death of the significant dead are not limited to their immediate and extended families. They are often engaged by those who imagine themselves to be related to the dead in one way or another, whether legitimately so or not. Thus, in claiming the dead person (and/or their things), a cultural crisis is activated or (re)produced, with implications for local, national, and sometimes international social, political, and economic relations. If politics is approached as “a form of concerted activity among social actors, often involving stakes in particular goals”—goals which may be contradictory, as evident in the case of Zik's death and burial—then it will also necessarily include “claiming authority and disputing the authority claims of others … and creating or manipulating the cultural categories within which all of those activities are pursued” (Verdery Reference Verdery1999: 23). Thus, the cultural crises triggered by the deaths of key persons is an important part of the general politics of death in contemporary society.

PASTNESS AND PRESENT POLITICS

Africa weeps over the transition of one of its foremost Pan-Africanists. The whole world has been deprived of a statesman par excellence, a literary giant and political colossus.

———General Sani Abacha, Nigeria's Head of State, oration at the lying-in-state of Azikiwe in Federal Capitol Territory, Abuja, 13 Nov. 1996.At the time of Zik's death on 11 May 1996, the regime of General Sani Abacha (Nigeria's maximum ruler, 17 November 1994–8 June 1998) was facing a crisis of legitimacy stemming from an earlier crisis sparked when his predecessor, General Ibrahim Babangida, annulled the 12 June 1993 presidential election. Abacha had seized power under the pretext of resolving that predicament, only to establish the most repressive and homicidal regime in Nigeria's history while working toward self-perpetuation in office. With a range of political, civil, and ethnic coalitions working hard to end his regime, Abacha saw in Zik's death an opportunity to gain some national legitimacy by ensuring a befitting burial for the “father of the nation.” The regime declared there would be a three-day “national mourning” and that the national flag would fly at half-mast for seven days.

Image 2. The front page of the Guardian newspaper, Lagos, with photo of Azikiwe lying-in-state there, 13 November 1996.

During the national crisis that led to Abacha hijacking power, and also thereafter, Azikiwe had refrained from making strong statements against the military regime. In so honoring Azikiwe, Abacha was targeting the man's admirers across the country, particularly among the Igbo in eastern Nigeria. By giving Azikiwe a “befitting burial” Abacha hoped to derive maximum benefits for his regime; this was part of his “transparent ploy for self-perpetuation” (Soyinka Reference Soyinka1996: 10). As Zik's body lay in state in the Federal Capital City, Abuja, Abacha announced that the airport there would be renamed Nnamdi Azikiwe International Airport, as “a token of appreciation of [his] immense contributions to nation-building.”Footnote 14 This acknowledged Zik's past sacrifices and attempted to gain political capital from doing so. President of Sierra Leone Ahmed Tejan-Kabbah presented a tribute to Zik on behalf of other African heads of state present in which he said that Zik had sensitized the rest of Africa to the “need for decolonisation” as a “touch-bearer in the dignity in the fight for the dignity of man [sic].”Footnote 15 Niara Sudarkasa, the President of Lincoln University, Zik's alma mater, stated that he would be remembered as “one of the twentieth century's most passionate and persuasive advocates of African self-determination and one of the unwavering champions of African unity and cooperation between Africa and the African Diaspora.”Footnote 16

To oversee Zik's state burial, the regime named a National Burial Committee led by Minister of Special Duties Dr. Laz Unaogu. The Committee arranged for the body to be taken to lie in state in all the three of Nigeria's old regions—homes to the three largest ethnic groups, Hausa-Fulani, Igbo, and Yoruba—and in Abuja. This would allow Nigerians from all the walks of life to bid their departed leader farewell. The first stop was his birthplace of Zungeru (north), followed by the Federal Capitol Territory, Abuja, Lagos (west) and Enugu (east), before the internment in his homestead of Onitsha on Saturday, 16 November 1996. The body was flown to all of these destinations (except for the Enugu to Onitsha leg) by a Nigerian Air Force Hercules 130 plane. I was the only journalist traveling in the plane, having been given official clearance through my contacts on the National Burial Committee. Nigerians, “irrespective of tribe and religion,” turned out at every stop on the journey, at the venues and in the streets. Abacha acknowledged this pan-Nigerian farewell in an address read at the internment on his behalf by his deputy, the Chief of General Staff, Lt. Gen. Oladipo.Footnote 17

At the International Conference Centre in Abuja, a procession of twelve pall-bearers, consisting of Army brigadier-generals and officers of equivalent rank in the other services, was led by no less than the number two man in the regime, General Diya. In his oration at Zungeru, the Niger State military administrator, Simeon Oduoye, echoed Tejan-Kabbah and Sudarkasa: “Zik's life was spent in transforming the dignity of Africans and [the] emancipation of the continent from the shackles of colonization and imperialism.”Footnote 18

Staking Succession: Death and the Crisis of Kinship

It is the evening of Friday, 15 November 1996, and I am standing in a corner of the living room in the Inosi Onira home of the recently departed Dr. Nnamdi Azikiwe in Onitsha. The internment is expected to begin in a few hours. A few family members are in the room condoling with, or more actively, standing by and with the widow, Dr. Uche Azikiwe. A university lecturer, Uche had been embroiled in both private and public disagreement with Chukwuma Bamidele Azikiwe, her late husband's first son from an earlier marriage to Flora, who died in 1983. Chukwuma Azikiwe, age fifty-six, bursts into the room for some uncertain business. He ignores the widow, his younger stepmother. The running battle between them since the departure of their eminent patriarch has been primarily over who has priority in arranging for the burial.

Without doubt, all the relations and friends of the widow and family members in the living room knew of the on-going cold war between the two, since no one seemed surprised that the heir ignored the widow. Nor was I, since I had been writing journalistic stories about their family since the great man's death. In the course of my reporting, I had spoken with Chukwuma a few times. Though I could not speak with the widow directly, I was in constant touch with some of her supporters, who provided intimate details of her thinking and position on the issues and controversies. Some of the details I gained from these background interviews and from documents I received from sources were included in my news reports as the country and the family prepared for the burial.Footnote 19

It is apposite to point out here that the connection between the personal or familial and the political in Zik's burial was inevitable due to his combined cultural and political eminence, which for his family members reinforced each other. Burying the dead in their homestead is a common practice in many African societies, particularly so among the Igbo, as Daniel Jordan Smith has shown (Reference Smith2004). The process of doing so often (re)produces tensions, but Zik's political significance meant such tensions ran deeper, with broader ramifications for family members and for the leaders of his ethno-cultural group. As Smith points out, the tensions around “Igbo burials crystalize latent conflicts and make them worse” (ibid.: 570).Footnote 20 Worse still are the tensions that surround burials of the politically eminent dead. The national attention that Zik's burial attracted meant that the “latent conflicts” at the personal level were eventually projected into the public processes of burial and commemoration. Additionally, what the different persons and camps within the family believed to be at stake required that, in order to strengthen or leverage their own positions, they transform “invented traditions” (Hobsbawn and Ranger Reference Hobsbawn and Ranger1983)—that is, “historically wrought phenomena, often ones of relatively recent vintage” (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff2018: viii)—into immemorial Igbo customs and practices (see Afigbo Reference Afigbo1972).

“Death is an event that presents a crisis to the family system,” argue Van Meter and White (Reference Van Meter and White1982: 235). This particular crisis regarding kinship rights, conjugal rights, descendant rights, cultural supremacy, and other things was defined by the combatants according to “traditional” and “modern” precepts. Though the disagreements within the family preceded Zik's death, his demise complicated and intensified them and turned them into a public crisis. Thus, the absence of the mediator (the late patriarch), who was however not regarded by all sides as a conciliator, gave the opposing parties a measure of free rein in staking claims. Within the Igbo cultural worldview, hardly any death is natural (Anigbo Reference Anigbo1982: 521),Footnote 21 but Zik's immediate family did not worry about explaining his death—their concern was what each of them could gain from it.

In the battle for material and symbolic inheritance and succession, the major gladiators were the Diokpala Owelle (hereditary heads of Zik's family): Zik's son Chukwuma and his widow. Many who claimed to be standing on the authority of “tradition” supported Chukwuma. These included the traditional ruler of Onitsha city the Obi of Onitsha, the Obi-in-council, and the Umu Ada Ogbeabo (daughters of the town, Ogbeabo being Zik's village in Onitsha). The widow Uche, on the other hand, was supported by those who accepted that the interests of the “modern” authority (the military government) was paramount and overriding in every case, even if they contradicted “tradition.” The latter group was largely represented by the National Burial Committee and some Igbo politicians who hoped to use the burial to gain either access to, or greater influence with, the military regime.

Again, the grounds for the crisis were determined long before Zik died. He had four children with his first wife, Flora (nee Ogoegbunam), who died in 1983. Zik married his third wife, Uche (nee Ewah), in 1973 when she was twenty-six.Footnote 22 They had two children together. It is unclear exactly when he married his second wife, Ugoye Comfort Azikiwe (nee Aneche), with whom he bore three children. She died four years after Zik, in 2000.Footnote 23 Some sources I spoke with in 1996 suspected that the problems in the family were partly the result of Zik's polyamorous life, though he never lived with more than one of the women at a time. Be that as it may, his son Chukwuma, alongside Chukwuma's mother Flora (until her death) and his three siblings, feuded with his father for many years before he died.

When Chukwuma and his allies began their battle against Uche to ensure that the Federal Military Government designated his first son as the “Chief Mourner” and that he and his constituents would determine where and when Zik would be buried, Uche not only issued a public statement, but also allegedly released to the National Burial Committee private letters that Zik had sent to Flora and her children over the previous decade and a half. When I was a reporter for the Nigerian Tribune a source gave me photocopies of these letters. Uche wanted to convince the Committee that Zik was estranged from his late wife and her children and, on that basis, ensure that Chukwuma was neither granted any official status nor allowed to play a major role in his father's burial arrangements. In one of the letters that Zik wrote to Flora, dated 23 November 1982, he expressed great disappointment that she and their four children—Chukwuma, Chukwuemeka, Nwachukwu, and Ngozi—had sent him no felicitations on his seventy-eighth birthday, particularly so since this was after he had made a medical trip to the United Kingdom and the United States. He reminded Flora that he had specifically warned Chukwuma and Ngozi not to “enter into or set their foot in any of my houses at Onitsha or Nsukka,” though they “are entitled to the Iba Azikiwe [the family house in their village] which is our common heritage.” Most important in this letter, ostensibly for the widow, was a part in which Azikiwe stated, fourteen years before his passing, that he had “enjoined [Chukwuma and Ngozi] not to bother to attend my funeral, in case I go the way of all flesh.” He did add that he bore “no malice … and no grudge against them.” Zik repeated this wish in another letter to Chukwuma dated 23 November 1982, in which, after complaining that he had “not seen or heard from [his son] for three years,” he stated, “Should I go the way of all flesh, don't bother to attend my funeral.” He concluded the letter with “Goodbye.” Another letter, written to Chukwuma almost a year later, on 17 October 1983, regarding the “memorial service for Amalunwaeze [Flora],” accused him and his brothers of planning the “funeral obsequies of my dear wife [Flora] … without previously consulting me.” Zik reminded Chukwuma that, “like other Igbo communities, we are patrilineal in our cultural practice of primogeniture,” and thus women “usually recede into the background,” though he added, “We do not necessarily discriminate against our women.” Ironically, thirteen years later, Chukwuma and his supporters were trying to use exactly such “(Igbo) cultural practice,” as enunciated by his father, to prevent Uche from taking the lead in planning Zik's burial.

But so far as Uche was concerned, these and other letters showed that Zik was not only estranged from his children by his first wife, but was emphatic that he did not want them to attend his funeral, let alone be involved in organizing it. When the Burial Committee members received Zik's letters they were convinced about Zik's attitude toward the children from his first marriage, particularly Chukwuma, and yet they were initially confused about what to do. Eventually, they concluded that since Chukwuma and his allies wanted to make decisions for the federal government on how and where to bury the great man, they had to side with the widow.

As John S. Mbiti has argued, burials in Africa are occasions for affirming kinship ties and reifying the social order (Reference Mbiti1969: 149–65), and Stamp correctly notes that the burial site is a “significant part of this affirmation” (Reference Stamp1991: 833). In the present case, there were three key controversies around which the two camps organized their struggle for the affirmation of kinship ties as well as socio-cultural and/or political primacy. When the New York Times in its obituary for Zik stated that a holder of a traditional title such as Zik “is expected to have an elaborate funeral guided by ancestral customs” (French 1996), the paper could not have imagined the crisis that would be enflamed by controversies over what these “ancestral customs” actually were and who would make the decisions regarding them. Given that this was regarded as an opportunity for Chukwuma and his constituents to get even with their patriarch's “other” wife, Uche (and even, for Chukwuma and his siblings, with their late father), authority over the funeral rites had to be contested in every way.

The first controversy swirled around the nature of the socio-cultural and political succession that would follow Zik's passing. This included the inheritance of Zik's title and cultural status, and for some outside the family, his political status. More importantly, particularly regarding the ceremonies to mark Zik's transition, who would be the symbol and the voice of the family and ultimately make decisions on the family's behalf? If Zik no longer spoke as the family's head, who could speak for him or in his place? In light of Zik's estrangement from his four eldest children and the death of his first wife, his surviving wife Uche, who had lived with and nursed the old man until his death, felt that she was the natural inheritor of this status. But as is the practice in “Igbo culture” under normal circumstances, the Diokpala Owelle Chukwuma felt that he was the rightful inheritor of this position. While “secular” governmental authorities could recognize the written wishes of a man such as Zik, “trado-religious” authorities such as the city's traditional ruler Obi of Onitsha and his council of chiefs would not recognize or accept anything that stood tradition on its head. Zik himself had articulated this in his 1982 letter, writing, “we are patrilineal in our cultural practice,” and as a result of this, in cultural matters, women “usually recede into the background.” Thus, the Obi supported Chukwuma.

Uche, though, despite the traditional ruler's edict, was not ready to submit to her stepson's authority. Thus, the Obi, Igwe Okechukwu Okagbue, who tradition empowered to break the news of the death of a red-cap chief such as Zik, initially ordered the Onowu Iyasele (the traditional prime minister of Onitsha) to announce the passing of the Owelle and “coordinate the burial activities by liaising with [Zik's] family, especially the eldest son, Chukwuma.”Footnote 24 When Uche contacted the federal government to formally announce her husband's passing, the Obi, other chiefs, and Chukwuma regarded this as a breach of tradition. Perhaps in reaction to Uche, and to confirm Chukwuma's primacy, two weeks after Zik's death the Obi asked Chukwuma to formally announce his father's passing and lead the delegation to formally “break the news” to the head of state General Abacha, in Abuja.Footnote 25

The second controversy was about what might be called the spatial politics of burial. Although there were cultural rules at stake here, too, each party mobilized the argument in the service of their interests and what they hoped to gain by the decision on where Zik would be buried. In many parts of Africa, as a manifestation of the “politics of belonging,” as Peter Geschiere has argued, “it is still of utmost importance to be buried in the village of origin” (Reference Geschiere, Diouf and Fredericks2014: 51). The “stigma of social disgrace” (ibid.) attached to being buried in the city is no longer as prevalent as in the past, especially among urbanites who either are culturally inconsequential back home or no longer have strong roots in their village. Nonetheless, the case of Zik was complicated because Onitsha, though a city, was also his homestead. However, within Onitsha's cultural politics, Ogbeabu village, his father's homestead in the outskirts of Onitsha, was his real homestead. In this way, this case complicated the idea of homestead or natal village.

Chukwuma, backed by the Obi, the chiefs, and other family members insisted that, as the Owelle (sixth in rank among the first-class chiefs), Zik had to be buried in Iba Azikiwe (Zik's father's homestead) in Ogbeabu village. This would ensure that Chukwuma and the traditional leaders had maximum control over the burial rites. Their position was couched, culturally, in the language of “proper burial” for the Owelle. Uche, and Zik's children from his two other wives, knew this would disadvantage them and objected strongly. They charged that the burial of such a great man in a village, which would be attended by leaders from around the world, was an attempt to “disgrace” the late Owelle.Footnote 26 For Uche, Zik's “proper burial” had to be in his city home in Onitsha. She sent a letter to Laz Unaogu, the chairman of the Burial Committee, copied to fifty top Nigerians, which stated, “My husband's wish was that he be buried in his ‘Iba’ [his personal homestead] at Inosi Onira Retreat, Onitsha.”Footnote 27 She cited the authority of “tradition” to bolster her position: “Besides the fact that Owelle wished to be buried in his own house … according to tradition, the opinion [is] that a man is buried in his compound unless the person is a failure in life and has no house of his own, then he is buried in his father's house.” In addition to describing Chukwuma as a “bully” who was “cantankerous” and had “devilish plans,” the widow added a threat, perhaps to signal her seriousness to Chukwuma and his supporters: “I will resist with the last drop of blood in my vein any move by Chuma [Chukwuma] or his cohorts to disrespect my late husband's wish…. Owelle will never forgive me for letting him down because I know there was no love lost between him and his son, Chuma, and he confided in me the happenings between the two of them.”Footnote 28 This battle over “culture” or “tradition” is yet another reminder that either is constituted by “polyvalent, potentially contestable messages, images, and actions” (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1993:10).

Perhaps the only major supporter of Uche in the family was Zik's only sister, Akakulia Cecilia E. Arinze-Modebe. Uche ostensibly persuaded Cecelia to send a letter, dated 27 July 1996, to the chairman of the Burial Committee, in which she stated, “By our culture and tradition a man is buried in his ‘Iba,’ therefore, the right resting place for Owelle as Idi-iche Ume is Inosi Onira Retreat.”Footnote 29 Doing otherwise, she asserted, “will amount to a dishonor to his gentle spirit and I will not be a party to such a decision.” Zik's half-sister, Mrs. Obiageli Ifejika (nee Azikiwe), took a different stance, announcing that, like his father, Obedodan Azikiwe, and Zik's first wife Flora, Zik had to be buried in Ogbeabu. Any other place of burial, she said, would constitute, “the bush,”Footnote 30 where a “proper” Igbo man cannot be buried.

These rival claims raised the question of whose tradition was at stake. The battle between Uche and Cecelia on one side, and the men in charge of traditional authority on the other, mirrors Lee and Vaughan's argument that “the dead could only find their place as ancestors, rather than vengeful ghosts, if their loss had been properly registered, not only by the individuals closest to them, but by the social groups to which they were members” (Reference Lee and Vaughan2008: 342). Uche's expression of fear of Zik's anger if she allowed him to be buried against his wish points to the potential of an ancestor becoming a “vengeful ghost.”

Could these women—the deceased's widow and sister—who, according to Igbo “tradition,” were supposed to, to use Zik's words, “recede into the background,” know better than the men? It was evident that the gender dimensions of lineage relations that could have disadvantaged these women was being simultaneously challenged and mobilized to leverage their position because the ultimate arbiter in this matter was a “secular” authority in Abuja that, in a sense, was far removed from these traditions (see Stamp Reference Stamp1991; Gordon Reference Gordon1995). The gender issues at stake in this crisis were not as intense as in the case of Wambui Otieno, who had to sue the family of her late husband, prominent Kenyan lawyer, S. M. Otieno, over the burial of his remains (see Cohen and Odhiambo Reference Cohen and Odhiambo1992). Yet it shared features with that case, including the way in which the principals deployed “tradition” as “a potent invention” (Stamp Reference Stamp1991: 810).

It was significant that, apart from Zik's sister, most of the women in the community supported the “prerogative” of the patriarchal authorities in cultural matters. The Umu Ada, the daughters of the (Ogbeabu) village, joined the debate in support of Chukwuma and the Obi. They issued a statement condemning Uche for opposing the plan to bury Zik in the village and for insulting the Onitsha monarch. They subsequently “banned” her from attending the funeral rites and imposed a fine on her. They also reminded the public that, contrary to Uche's claim as “the sole surviving spouse of the Owelle … the current senior wife, Mrs Ugoye Azikiwe, is alive.”Footnote 31 The Burial Committee reacted by dismissing the Uma Uda's position, stating that the government recognized “Dr (Mrs) Uche Azikiwe as the only surviving wife of the late Zik.” They added, “This mater of bringing a woman from obscurity smarks [sic] of vendetta … to humiliate the late Owelle.”Footnote 32 The statement reminded everyone that “Zik's burial will be a state burial and as such, the traditional content … [will] be very low.”Footnote 33

The third controversy concerned the timing of the burial. According to tradition, as expressed by the Obi as a Ndichie Ume (first class red cap chiefFootnote 34), the Owelle should be buried at midnight. This would have created security and logistical problems, not only for the head of state, who planned to attend, but also for the foreign heads of state and other foreign envoys that would be there. These guests could not be expected to attend a midnight burial. While the Obi and most of his chiefs were insisting on this, a few Onitsha chiefs secretly contacted the Burial Committee and told them that “tradition” prescribed “sunset” and not necessarily midnight for a Ndichie Ume's burial. It was therefore decided that a compromise could be reached with the traditional authorities by ensuring that the actual burial would start at six in the evening. Yet, some government protocol officers and security chiefs disagreed, arguing that it would still be a logistical nightmare to transport the foreign VIPs from Onitsha to Lagos or Abuja at the end of the internment, which might last until seven or eight o'clock. The first challenge, they claimed, was that the limit for road travel by a foreign head of state was 40 kilometers. The nearest airport was in Enugu which was more than 100 kilometers from Onitsha. Helicopters were not an option because, ordinarily, civilian helicopters did not fly when flight or vision conditions were not optimal.

Eventually, due to the decision to bury Zik at sunset and the bickering in the family, the government decided to upgrade the Abuja lying in state so that Abacha and the foreign heads of state could attend that event, while the number two man in the regime, General Oladipo Diya, was asked to represent Abacha at the internment in Onitsha.

These controversies over death and funerary rites highlight how “traditional” understandings and practices of social relations are being altered. The crises provoked by the deaths of significant persons mirror ongoing transformations in the ways in which kinship ties are maintained and communal values and notions of succession are reproduced (Lee and Vaughan Reference Lee and Vaughan2008: 343–44). These controversies, including questions of how power and influence are distributed among inheritors along both kinship and gender lines, constitute a form of mediation between old practices and evolving social norms. For this reason, they also display contestations over what spiritual and philosophical orientations are acceptable in this evolving African society (ibid.).

Death (Hoax) and the Politics of Ethno-National Bereavement

His death is going to be that melting pot that we very much need to bring back everyone to the fold for the development of Nigeria.

———National Committee for Zik's Funeral Celebrations.When Zik died in 1996, most newspapers and television stations were reluctant to publish or air news of his passing. They had been chastened by having earlier reported news of Zik's “death” which turned out to be false. This time, only ThisDay newspaper had the courage to “break” the news, on 13 May, two days after he died,Footnote 35 although no one went on record to confirm the news. Some other papers, such as the Guardian, only found the nerve to report the news on 14 May, even while emphasizing—to avoid embarrassment if this proved to be another false alarm—that Zik's “age-long political associate, Chief Adeniran Ogunsanya, and the News Agency of Nigeria (NAN), among other sources … confirmed earlier reports of [Zik's] death.”Footnote 36 For its part, the National Concord that same day ran the headline, “Caution Greets Zik's death.”Footnote 37 Six days after its initial report and eight days after his demise, ThisDay still reported that many people, particularly politicians, were still “playing the dumb on Zik's death”: “Family members are unreachable, close associates would not talk, nobody would comment” due to “fear and deference.”Footnote 38 When ThisDay asked Dr. Chuba Okadigbo, the voluble Igbo politician, to comment, he shot back: “I read nothing, heard nothing, I can't comment on anything.”Footnote 39

Okadigbo had reason to be careful. He had joined two other prominent Igbo politicians in planning Zik's burial in 1989 when the man turned out to still be alive. Beyond that, when, as a young political adviser to President Shehu Shagari in the Second Republic (1979–1983), Okadigbo had dismissed Zik's criticism of the government as “the rantings of an ant,” Zik had reportedly cursed him by saying that Okadigbo would “die unsung for the futility of abusing old age.”Footnote 40 But why was everyone else wary of announcing or commenting on the passing of such a continental icon? Why was his death becoming a secret to be revealed later?

Zik had “died” a couple of times before. The rumored deaths of Zik are noteworthy in that they involved personal political calculations as well as the tensions of ethnic relations in Nigeria. His ethnic constituents were hesitant to announce or confirm his death partly in deference to Igbo culture, in which the death of such a high chief had to be announced by traditional authorities. However, many were also afraid due to their 1989 experience of Zik's rumored death at eighty-five, and the backlash that followed. In response to those rumors, Zik had reportedly said that those who wanted him dead would die before him. As it turned out, the two key political allies who announced the fake death did die ahead of Zik. “The belief,” the Sunday Concord commented, “is that Zik has a habit of resurrecting and if you announce or comment on his death, you're courting death yourself.”Footnote 41 The newspaper's editors, who decided not to publish the news of his passing until it was “official,” said they “were only erring on the side of caution.” All the newspaper editors that the Weekend Concord asked to comment on the reluctance to publish news of Zik's death pointed to “the 1989 experience.”Footnote 42

In early November of 1989, Zik's “death” was announced in the newspapers and on national television. Sitting in the living room of his Onuiyi Haven, in the university town of Nsukka, Zik watched as the Nigerian Television Authority (NTA) made the announcement. His wife Uche later revealed that when the couple first saw clips of the former president on television, they had assumed that the story was about his approaching birthday.Footnote 43 The TV signal from Lagos, then Nigeria's capital city, was poor, affecting both picture and audio quality, but Uche said they were a bit surprised when the station “began revealing his life story.” She reportedly thought this was “pretty early” for his birthday, still one and half weeks away. Only when they heard, “May his soul rest in peace” did they realize it was an obituary.

When what came to be described as “Zik's death hoax” in the Nigeria press became a huge political controversy, some zeroed in on the Nigerian Tribune, owned by the family of Obafemi Awolowo, who was Zik's great political rival and considered the leader of the rival co-majority ethnic group, the Yoruba. While rumors of Zik's death began to circulate, it was Tribune that had first published the “news.” On 2 November, in a tiny part of its front page, the newspaper asked, “Is Zik dead?” The report stated, “Speculations were rife late last night that the Owelle of Onitsha, Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe … died in his residence.” The next day, the paper decided to print the rumor as “truth” by announcing on its front page, “Zik Is Dead.” Other newspapers picked up the story the following day, with the Weekend Concord announcing on its front page: “Africa Losses a Colossus.”

On the basis of these reports and the rumors circulating the major cities of South West Nigeria, Zik's political colleagues sought to gain advantage from his passing, particularly two key associates: Chiefs R.B.K. Okafor and Kingsley Ozumba Mbadiwe, both Igbo politicians. They publicized their primacy in Zik's political camp and how close they were to the great man, and described to the media, with notable histrionics, their last engagements with him. Mbadiwe, a minister in charge of different portfolio's in Nigeria's First Republic, even issued a condolence message on behalf of a “122-man Committee on the Transition of Dr Nnamdi Azikiwe.”Footnote 44 The federal government-owned Nigerian Television Authority regarded this as a confirmation of an earlier message from Okafor, and its prime time network news telecast categorically announced Zik's demise. In turn, some hesitant newspaper editors took the NTA announcement as a confirmation and also went to town. Former editorial page editor of the Guardian, Professor Olatunji Dare, recalled how Okafor, a cabinet minister in the First Republic and former Chairman of the Zik-led Second Republic political party, the NPP, regaled the newspaper's editors with a story of his encounter with Zik on his death-bed, where, he claimed, Zik asked him to “take over the mantle of his political leadership.”Footnote 45 Okafor added that the dying man had called him “my son, my heir-apparent.”Footnote 46 It was apparent that Okafor's false claims were part of an attempt to leverage himself in the struggle for political succession expected to follow Zik's death.

Okafor did not stop with the Guardian; he made the rounds of newspaper offices and also sent a release to the NTA in Lagos.Footnote 47 When the hoax was exposed, Okafor and Mbadiwe were reportedly at “loggerheads” over who first informed whom about Zik's passing.Footnote 48 Mbadiwe told the press that Okafor “broke the news” to him, while Okafor denied that he could have done so given that Mbadiwe “had already issued his condolence message to the press without [my] knowledge.”Footnote 49

The foreign press joined in reporting the fake news. The obituarist of the conservative British daily the Telegraph obviously still harbored grudges from the sun having set on the British Empire due, in part, to the activities of anti-imperialist activists such as Zik. He dismissed Zik's three years in the old Gold Coast (later Ghana), where he had edited the African Morning Post, as a period when Zik was a “propagandist for the nationalist cause.”Footnote 50 A Zik admirer, Cameron Doudu, responded by dismissing the Telegraph writer as an “imperialist obituarist.”Footnote 51

However, for Lewis Obi, the African Concord's editor-in-chief, the most important culprit in the unfortunate incident was the Nigerian Tribune, given that its “owners are known not to be Zik's greatest friends.”Footnote 52 In a two-part opinion piece in his weekly column, Obi sought to draw attention to implications the Tribune's faux pas had for political and ethnic relations between Nigeria's two southern majority ethnic groups, Igbo and Yoruba. Stated Obi, “For the founder of the paper, Chief Obafemi Awolowo, had for over 35 years engaged Zik in a game of mutual political frustration till he passed on two years ago,”Footnote 53 a veiled reference to the Igbo-Yoruba rivalry that emerged during the two decades leading up to Nigeria's independence.

The military President Ibrahim Babangida had been strongly criticized in the Lagos-Ibadan press axis over his government's transition to a civil rule program and the Structural Adjustment Programme it had imposed on the country because of the economic crisis. Babangida now seized on this situation as an opportunity to further damage the press's credibility. In his message to Zik over the incident, he stated, “If this could be done to Zik, then it could be done to any person.”Footnote 54

When Zik actually died, in 1996, politicians of all ideological persuasions, particularly progressives, wished to use his burial to boost their legitimacy and credibility in the context of the ongoing transition to a civil rule program, which they feared would lead to Abacha's self-succession. They were quickly put on notice that they would not be afforded that opportunity. Newspapers reported in late May that the Abacha regime had resolved to “completely edge out” the progressives. Even Zik's political associates were to be “barred from participation” since the government wanted to “as much as possible depoliticise the burial arrangements.”Footnote 55 For the despot Abacha, this was a strategic form of anti-politics. The attempt to “depoliticise” Zik's burial was part of a larger strategy of depoliticizing politics in general so as to instrumentalize Abacha's ambition to continue in office as the sole candidate of all existing political parties (all of which later did nominate him as their “consensus” candidate). As Walima T. Kalusa has observed, “The significance of the dead … to the living and to the survival of political regimes should not be underestimated” (Reference Kalusa2017: 1138). The attitude of the Abacha regime did not stop Zik's associates, made up of the leading members of the Zik-led defunct political parties, the NCNC, the NPP, and the Zikist Movement he inspired, and other politicians including even Zik's political adversaries (see ibid., passim), from announcing plans to be involved in his burial.

Progressive politicians under the banner of True Progressive Party Grand Alliance (TUPGA), ostensibly a neo-UPGA of the First Republic (a coalition between Zik's NCNC and Awolowo's AG), formed a twenty-man committee to work out their role in the burial.Footnote 56 Zik's associates, too, formed a burial committee. It was apparent that the politicians were after the attention and political leverage they would gain by celebrating a popular and respected leader. Zik's associates issued a press release on “the irreparable loss … of this distinguished son of Africa in this century,” and warned that “the burial of [Zik] must on no account be treated as an ethnic or regional affair.” Rather, they wrote, it should be handled in ways “befitting of the national and international stature” of the departed statesman.Footnote 57 They met in Lagos on 24 May 1996Footnote 58 and adopted the name “National Committee for Zik's Funeral Celebrations,” under the leadership of Zik's associate and First Republic Information Minister T.O.S. Benson. They also appointed a fifty-man contact sub-committee headed by former High Commissioner to the UK Chief Mathew Mbu. Betraying their interests in ensuring maximum political gains from Zik's death and the burial plans, they even resolved to “use the late Owelle of Onitsha's burial as an occasion for resolving Nigeria's lingering political crisis.”Footnote 59 They added, “His death is going to be that melting pot that we very much need to bring back everyone to the fold for the development of Nigeria.” They also planned to include in their fold the main opposition movement in Nigeria seeking to end Abacha's military autocracy, the National Democratic Coalition (NADECO). The military regime ignored them, and eventually the efforts of the associates dissipated, given that all the material resources for the burial were mobilized by the federal and state governments.

Further evidence that the regime and the politicians merely sought to use Zik's name and accomplishments for their own interests was that, after the burial, Zik's mausoleum at the Inosi Onira Retreat was abandoned for twenty-two years. It became an eyesore as successive administrations, his political associates, and political heirs all failed to complete the project.Footnote 60 When his statue, cast in 1959, was “beheaded” during a riot in Onitsha in November 2005, neither the federal nor Igbo-state governors did anything to restore it. A few years later, some Nigerians abroad started a fund-raising drive to reconstruct the statue.

It was finally restored in January 2007 thanks to the generosity of one Mr. Henry Onukwuba.Footnote 61 Even when the estate was burned down in 2005, allegedly by the members of a separatist movement, the Movement for the Actualisation of the Sovereign State of Biafra (MASSOB), in their clashes with the police, neither the government nor Zik's admirers made any efforts to restore the building, despite repeated promises.Footnote 62 In November of 2017, twenty-one years after Zik's burial, his widow Uche had to appeal to the federal government and South East leaders to help complete his mausoleum.Footnote 63

It was eventually completed the following November and formally opened by President Mohammadu Buhari in January 2019. This was just a few weeks before the contentious presidential election in which he faced a formidable rival, Alhaji Atiku Abubakar of the People's Democratic Party. As the candidate of the All Progressives Party (APC) seeking a second term, Buhari was expected to do poorly in Zik's home region. Many therefore saw the completion of the mausoleum as an effort to win the support of the Igbo of southeastern Nigeria. The pro-APC media reported its completion as something the rival “People's Democratic Party failed to do during all its 16 years in power.”Footnote 64 The import of this conclusion for the electioneering campaign in its South East stronghold was not lost on the PDP. One of the party's chieftains in the region denied that the credit belonged to Buhari, and he reminded people of a disparaging reference Buhari had previously made regarding the relatively few votes he had received from the Igbo South East in his first election. Stated Chief Charles Udeogaranya, “The credit for Onira Retreat Centre [where] Zik's Mausoleum [is located] goes to Gen Sani Abacha and President Goodluck Jonathan [of the PDP who was defeated by Buhari in 2015] for laying the foundation and completing the project nearly by 97 percent and not to President Buhari who did a three-percent job on it in a region he claimed he gives only five per cent of his attention.”Footnote 65 The party chieftain's statement was a testament to the unending struggle by the living compatriots of the deceased to make political gains from his memorialization.

CONCLUSION

In the early morning of Wednesday, 13 November 1996, I had just arrived at the Abuja airport to board the Hercules military aircraft that was taking Zik's body round the country. As I opened the car door to make my way toward the tarmac in the airport's VIP area, my friend, Alabi,Footnote 66 who was dropping me off at the newly renamed Nnamdi Azikiwe Airport, Abuja, warned me, for the last time, against flying in an aircraft bearing Zik's corpse. Alabi reminded me that powerful men such as Zik did not die without “taking some people with them.” He linked the start of Zik's obsequies with the crash of an ADC Boeing 727 plane in Lagos the previous Thursday.

In Africa, the transition of persons considered to be extraordinary activate (re)considerations of their assumed spiritual/occult potency, including whether that potency will survive them. Alabi's position expressed the belief in some cultures in Africa that great events in the life of powerful men sometimes involve sacrificing other lives. Such events can be the installation or death of a powerful king or of leaders with occult or magical powers. As ThisDay reported, many believed that “Zik, for whom they had created a great aura of mythologies, is not an ordinary mortal and gods don't die.”Footnote 67 In light of this, it was alleged that “some nurses [ran] away from their posts when they heard of [Zik's] eventual death. They believe such as man could not die without dragging some people along with him. And they were not ready. Not even for the opportunity of accompanying a god.”Footnote 68 The great man's death therefore created a crisis of looming death for lesser mortals.

In her recent work, Anti-Crisis, Janet Roitman alerts us to the manipulative uses of “crisis” in contemporary society (Reference Roitman2013: 2–3) and notes that “crisis” was originally “a signifier for a critical, decisive moment.” As a concept, she adds, “crisis is mobilized in narrative constructions to mark out or to designate ‘moments of truth’ … turning points in history, when decisions are taken or events are decided, thus establishing a particular teleology.” Crisis in the sense in which I have employed it in this essay has different aspects. However, I prefer to describe it as cultural because the convergence of the different aspects of such a crisis foregrounds fundamental human relationships, reproduced by how the community, different social formations, and individuals within and beyond the community of the dead assess the value, significance, and place of the dead in history.

In arguing that the deaths of significant persons in Africa can generate cultural crises, I will add that their burial often translates into crisis management, as is evident in the case examined here. Therefore, the manner of deciding on the socio-cultural process of transition, that is, the burial (including the different rituals, ceremonies, public memories, delivery of eulogies, and internment) is often in contention. Even when there is widespread consensus on the import, place, and meaning of the dead in society and history, the recognition of “minority” opinions, often strong ones, or dissension regarding any of these (i.e., the significance, place, or meaning of the dead person's life) generates vigorous attempts to defend the dead against particular memories, modes of commemoration, accounts of history, and modes of appropriation.Footnote 69

That said, it is important to state that crisis in the sense I use it here does not necessarily imply that those engaged in these struggles are motivated by negative impulses. In this context, the crisis could be brought on by positive and laudatory attempts to control a piece of the dead person; that is, to stake a claim on their legacy (even an exclusive one) or appropriate it. Nevertheless, the struggle to assert such claims or appropriate the dead and the values associated with them often trigger negative or disruptive counteractions as people impress their interests onto the dead. This is particularly common when the struggle is about the management of their “legacy” or their “remains,” by which I mean the whole panoply of what remains of the dead. This includes not just their literal remains (the cadaver), but also their metaphoric remains such as the deceased's property, image, reputation, relationships, and significance, and their roles in families, clans, communities, and ethnic/national groups. By engaging in these struggles, individuals and groups turn death into a cultural crisis. This is why, upon the death of a significant person, history (the past) and relations (in the present and the future), and the socio-cultural parameters for deciding on and managing these, often become matters of dispute.

One might argue that the basic elements I have described here are partly true of any death, varying only in scale. The difference is that here there is greater possibility and salience of crisis because there is much more at stake when important people die. This is because of the value, valuation, and dimensions of their private and especially public relationships, the politics of authority claims and counterclaims about cultural categories involved when such persons die, and the manipulation of those categories. Also important here is the remaking of political (as well as cultural) time provoked by the passing of, say, the Ur-patriarch—“the father of the nation.” This can occur not only when the deceased will be widely missed, as with, for example, Azikiwe, Nelson Mandela, and Kwame Nkrumah, but also when the passing elicits widespread jubilation, as did the deaths of Nigeria's Sani Abacha and Zaire's Mobutu Sese-Seko.