I. Introduction

In 2017, 47,600 Americans died from an opioid-involved overdose, and 2.3-6 million persons had an opioid use disorder (OUD) — a small fraction of whom received evidence-based treatment.Reference Hedegaard, Miniño, Warner, Charumilind, Latkovic, Lewis, Mendez-Escobar, Saloner, Karthikeyan, Lembke, Chen, Sandoe, Frye and Frank1 Medications are central elements of evidence-based treatment of OUD because they substantially reduce risk of overdose and improve functioning.Reference Haffajee, Bohnert, Lagisetty, Pitt, Humphreys, Brandeau, Larochelle, Bernson, Land, Schwartz, Gryczynski, O'Grady, Walley, Xuan, Hackman and Sordo2 High drug prices for brand-name products for treating OUD — most notably for the leading buprenorphine product Suboxone — limit the volume of drugs that can be purchased and made accessible to the public. High drug prices are especially problematic for public programs that disproportionately purchase OUD medications and rely on budgeted systems and grant programs, such as those authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act and SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act.3

In the buprenorphine market, brand-name manufacturers have exploited Food and Drug Agency (FDA) regulatory procedures, provisions of the Hatch-Waxman Act,4 and other patent policies to deter generic entry so as to maintain high prices and reap substantial profits. Specifically, Reckitt Benckiser manipulated the availability of its first branded buprenorphine formulations to drive demand for its newer film formulation, Suboxone. Reckitt Benckiser and a partner company also filed several questionable citizen petitions, engaged in Risk Evaluation and Mitigation System (REMS) abuses, and generated patent thickets to deter generic entry into the buprenorphine market. Although practices to block generic entry have garnered increased scrutiny in recent years, actions limiting the practices have been limited — to the detriment of widespread buprenorphine access.

In this article, we use the case of Suboxone to demonstrate egregious anti-competitive practices that delay generic entry, estimate the costs of these delays to the public, and suggest legislative and regulatory reforms to prevent these practices going forward. In Part II, we outline Reckitt Benckiser's anti-competitive tactics designed to extend their brand name products' exclusivity, and we use an event study framework to estimate the potential savings that would have been realized had enhanced competition from generics been introduced in the buprenorphine market in Part III. In Part IV, we favor prescriptive changes to address these brand firm behaviors over the largely procedural and clarifying steps taken thus far by the FDA. These include steps to modernize the Hatch-Waxman Act, enactment of the Creating and Restoring Equal Access to Equivalent Samples Act of 2018 (CREATES Act), and a compressed timeline for brand firms to challenge new products, among other concrete recommendations. We conclude in Part V that such reforms could address anti-competitive tactics engaged in in the buprenorphine and other drug markets going forward.

II. Suboxone's Rise to Market Dominance

Buprenorphine in combination with naloxone is the dominant formulation used in treatment of OUD with medication. The brand name drug originally with this formulation, Suboxone, was introduced in 2002 and lost patent protection in 2009. But the manufacturer Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals Inc. engineered patent exclusivity extensions using a variety of anticompetitive tactics over the years. These practices exploited loopholes in U.S. generic drug policy and, as a result, allowed Reckitt Benckiser to maintain very high prices for its brand-name products.

a) A Brief History of Suboxone

Subutex and Suboxone tablets were launched in 2002 as the first brand name buprenorphine products. The products were not eligible for the 20-year patent term granted to new drugs, because their active ingredients were no longer under patent protection.Reference Moraff5 Instead, the FDA designated these products “orphan drugs” entitled to 7 years of exclusivity, as it deemed Reckitt Benckiser unlikely to recover the cost of developing and marketing the drugs.6 Buprenorphine is a partial agonist that binds to the μ-opioid receptor; it acts to reduce painful symptoms associated with opioid withdrawal and block the euphoric effects of opioids.Reference Schuckit7 As a partial agonist, buprenorphine has a ceiling effect and its euphoric effects plateau rather than increasing with higher dosing.8 Because it has some potential for abuse, buprenorphine is a Schedule III drug on the Controlled Substances Act Schedules.9

Whereas Subutex is a buprenorphine-only product, Suboxone is a combination buprenorphine-naloxone formulation. Both buprenorphine-only and buprenorphine-naloxone products have favorable safety profiles and are clinically effective in mitigating opioid withdrawal symptoms and reducing cravings among those with OUD. However, the buprenorphine-naloxone combination product potentially deters abuse of the medication, because naloxone (an opioid antagonist that blocks the effects of opioids at the receptor sites) dominates drug effects when the combination product is crushed and injected.10

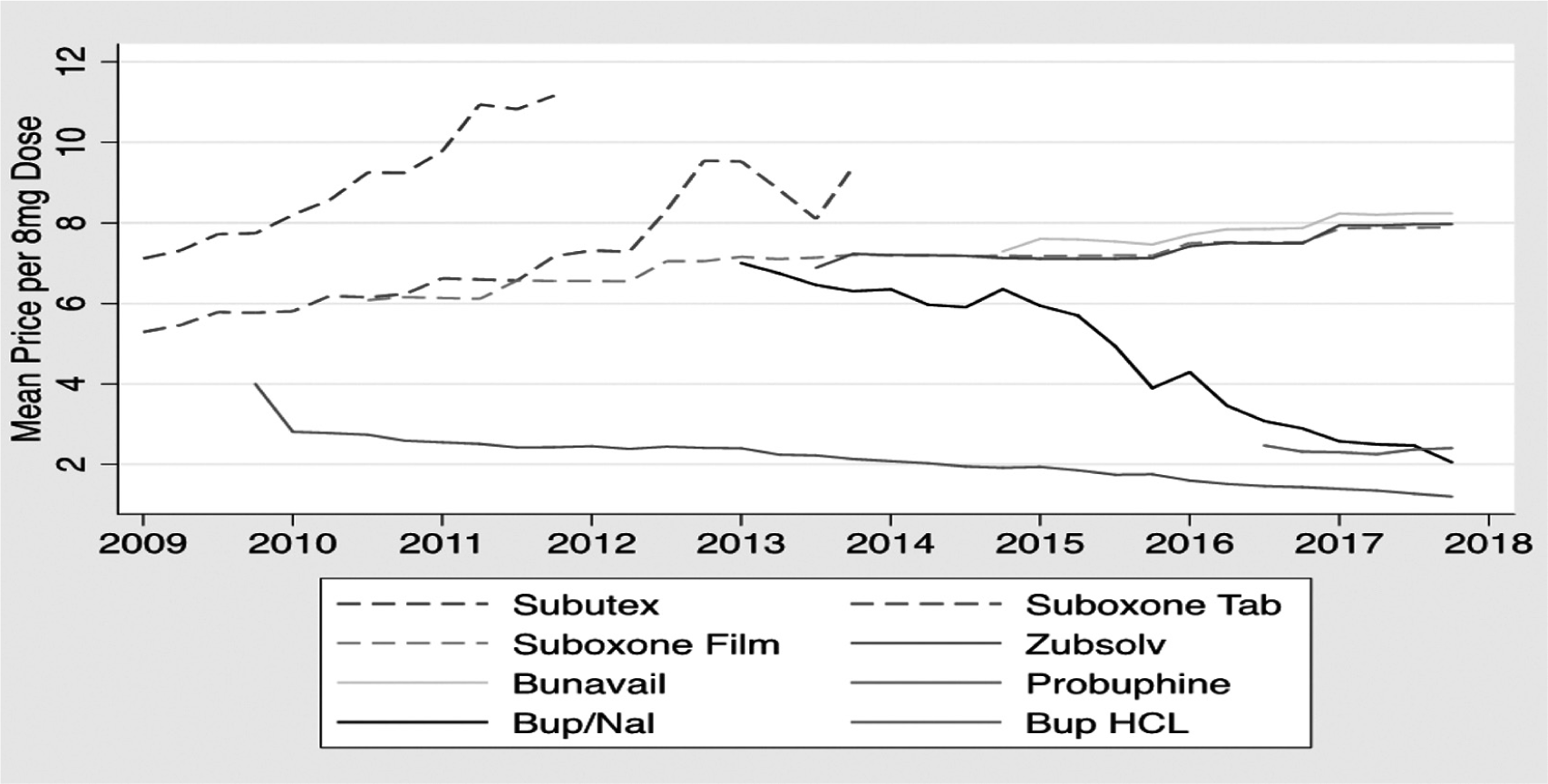

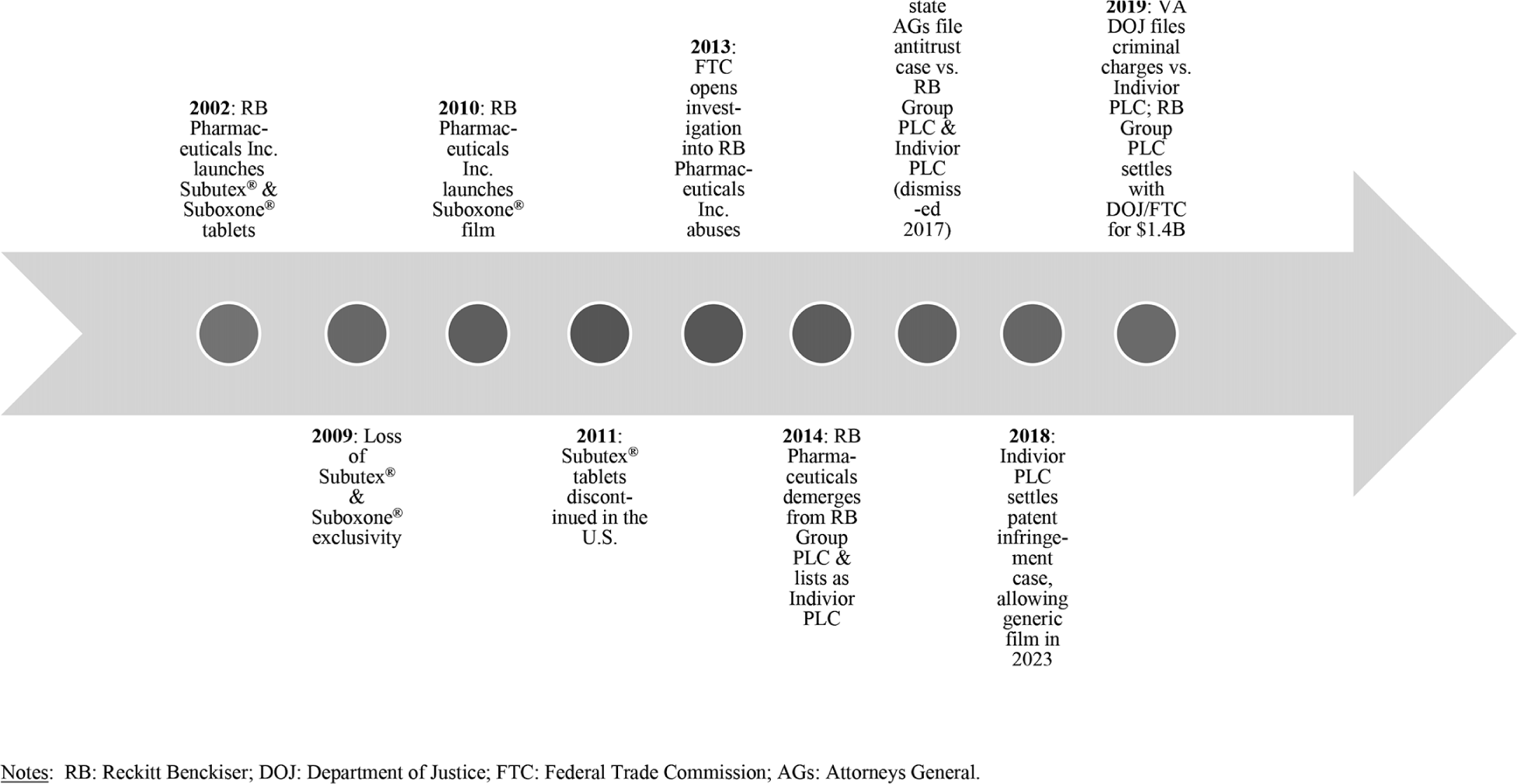

Subutex and Suboxone tablets remained the only buprenorphine products available through 2009, when generic tablet formulations entered the market following exclusivity expiration. Reckitt Benckiser removed Subutex from the market in 2011, following a notable price increase, only after introducing the sublingual buprenorphine film version of Suboxone in 2010 (Figures 1 and 2). The film was developed in partnership with Monosol Rx and was protected by multiple patents — the earliest of which expires in 2023.11 Since 2010, sublingual film combination products have dominated the buprenorphine market (Figure 1). These combination formulations allegedly make the product even less subject to misuse, as according to the manufacturer, the film inhibits tampering to a greater degree than the tablets.12 In 2014, Reckitt Benckiser Group PLC (the parent U.K. company) separated from Reckitt Benckiser Pharmaceuticals, Inc., which was thereafter listed as Indivior PLC — a group specializing in addiction treatment that manufactures Suboxone.13

Figure 1 Buprenorphine and Buprenorphine/Naloxone Price by Product

Source: IQVIA transactional data warehouse of buprenorphine sales by product for 2009-2017.

Figure 2 Suboxone Timeline

Suboxone accounted for roughly $2.58 billion in sales in 2017.14 Other manufacturers have introduced various other buprenorphine products in recent years. These include Zubsolv (launched 2013, a generic buprenorphine/naloxone sublingual tablet); Bunavail (launched 2014, generic buprenorphine/naloxone film formulation); Probuphine (launched 2016, branded implantable buprenorphine formulation); and other generic buprenorphine-naloxone tablet combinations and buprenorphine tablets (Figure 1). Also, in 2018, Indivior launched Sublocade, an injectable, extended-release form of buprenorphine.15 However, low reimbursement, clinical delivery challenges, and lack of product familiarity among providers for the injectable and implantable buprenorphine formulations have prevented their widespread use (Figure 1).16 Two generic buprenorphine-naloxone film formulations were just launched in 2019, after the developers won a series of court victories over Indivior, which sought to block their entry.Reference Jensen17 Figure 1 shows the price patterns for buprenorphine-related products over time. All the generic formulations are priced much lower than the branded products — including Suboxone that dominated the market for over a decade. Suboxone retained a 57% market share in 2017, below its 2009 peak of 85%.Reference Alexander18 To maintain its high prices, Reckitt Benckiser leveraged FDA regulatory processes, Hatch-Waxman Act provisions, and patent rules to deter generic entry and maintain high prices. These high prices for products in great demand, particularly in the midst of an opioid crisis, in turn put tremendous pressure on government budgets, reduce affordability, and hamper access to life-saving treatment. In the next sections, we explore specific tactics Reckitt Benckiser deployed in these buprenorphine markets, including product hops, REMS abuses, and citizen petitions.

b) Product Hops

The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984,19 commonly known as the Hatch-Waxman Act, sought to achieve a balance between rewarding innovation through the granting of market exclusivity to patent holders and promoting robust competition once a patent is found to be invalid or expires.20 It provides an abbreviated pathway (abbreviated new drug application (ANDA)) for generic products to enter the market by allowing them to demonstrate bioequivalence to an existing product with a patent listed in the FDA's Orange Book (a compendium of drug patents) instead of results from human testing.21 In constructing the balance, the Hatch-Waxman Act includes extensive due process related to patent challenges that offer fairness to innovators and opportunities to delay generic entry.22

Product hops refer to a sequence of actions taken by a brand name prescription drug manufacturer that is expected to soon face competition from a generic version. First, a brand name drug manufacturer launches a reformulation of a brand name prescription drug product that offers few or no additional clinical benefits to patients. Then, the brand name firm tries to reduce demand for the original formulation by employing tactics ranging from price increases to strategic promotional activities, such as detailing and advertising (“soft hops”), to removal of the original formulation from the market (a “hard hop”).Reference Feldman and Frondorf23 These activities can be pursued either before (more typical) or after the launch of a generic version of the original formulation. By doing so, brand firms establish a clientele for a version of the product that will not be subject to automatic substitution by pharmacists and doctors, as is the case with drugs that have an AB therapeutic equivalence rating (FDA recognized “chemical carbon copies of brand name drugs”).24 Thus, product hops serve to insulate the brand product facing generic competition from being substituted for a generic version by a pharmacist. The practice can lessen competition and elevate prices above competitive levels.25 Product hops depend on Hatch-Waxman Act regulations that bestow additional periods of market exclusivity to reformulated products approved for marketing.Reference Fowler26

Reckitt Benckiser had strong incentives to engage in product hops to maintain its market exclusivity for Suboxone, given that generic entry typically involves very rapid price decreases and large losses of market share for the brand name drugmaker.Reference Berndt and Aitken27 As Figure 1 demonstrates, Reckitt Benckiser first raised the prices of both its Suboxone and Subutex tablets prior to generic entry to reduce demand for these drugs prior to launching its reformulated Suboxone film. It also heavily promoted and offered discounts and rebates for its new Suboxone film to prescribers (i.e., “soft hops”).28 The company then engaged in product “hard hops”, when it withdrew branded Subutex tablets and Suboxone tablets in favor of reformulated Suboxone film. The successful product hop permitted Reckitt to steadily increase the film price.

c) REMS Abuses

REMS are regulatory actions aimed at managing the safety risks associated with prescription drug products. REMS were put into place in order to facilitate the rapid approval of drugs where there was evidence of potentially harmful side effects. By having a plan in place to attenuate risks prior to launch (or as new information becomes available), FDA aimed to increase the likelihood that the risk-benefit profile of new products would be as favorable as possible.29 The FDA has unilateral authority to decide if REMS is necessary and to enumerate the specific provisions contained in a REMS.Reference Dabrowska30 As part of the typical drug review and approval process, a manufacturer and the FDA agree on strategies that address safety risks. REMS typically consist of at least one of the following three components: 1) additional labeling information that provides consumers and physicians with further guidance on the drug; 2) a communication plan to inform potential users and physicians of the medication's risks; and 3) so-called Elements To Assure Safe Use (ETASU) that define how and under what conditions a drug can be used.31 ETASU include monitoring and testing of patients while they are using the drug and special restrictions on distributors or prescribers.32 ANDAs for generic products where the originator drug is subject to REMS must comply with the REMS terms, including Single Shared REMS (SSRS) — an FDA mandated collaboration between the branded manufacturers and generics.33

The importance of REMS to pharmaceutical markets is growing. Recent data suggest that about 40% of new FDA approvals are subject to REMS.Reference Brill34 REMS requirements increasingly include restrictions on the distribution of drugs. Brand-name drug manufacturers have been using REMS in innovative ways to limit generic competition. First, brand-name manufacturers regularly refuse to share drug samples with generic manufacturers seeking to bring a competitive product to market, claiming that ETASU provisions restrict when and how the drug can be used, thereby hampering generic producers' establishing of bioequivalence.35 This practice persists even though FDA has publicly asserted that sharing samples for bioequivalence testing does not violate REMS obligations and considers the practice to be exclusionary conduct.36 Second, brand-name drug makers refuse to include generic products in the obligatorily shared REMS system for equivalent products, thus blocking FDA from approving the ANDA.37 Third, under a REMS system, branded drug firm manufacturers can restrict the distribution of a drug to specialty pharmacies, hospitals or a specialty clinic as part of their harm prevention strategy where automatic substitution of the branded product for the generic is far less likely. All three of these mechanisms can pose important barriers to entry.38

Suboxone is a classic case of a drug needing a REMS, because it is an opioid partial agonist and subject to misuse, leads to REMS being used to blunt competition. Prior to loss of exclusivity for Suboxone tablets, Reckitt Benckiser proposed a REMS to the FDA. The request was approved, and the FDA required an SSRS for the branded and generic tablets. No cooperation materialized between generic ANDA filers and Reckitt Benckiser while the FDA took no action.39 The process of trying to agree on an SSRS lasted nine months until the generic manufacturers applied to the FDA for separate REMS, which was granted. Reckitt Benckiser profited approximately $1 billion from the delay.40

Suboxone is a classic case of a drug needing a REMS, because it is an opioid partial agonist and subject to misuse, leads to REMS being used to blunt competition. Prior to loss of exclusivity for Suboxone tablets, Reckitt Benckiser proposed a REMS to the FDA. The request was approved, and the FDA required an SSRS for the branded and generic tablets. No cooperation materialized between generic ANDA filers and Reckitt Benckiser while the FDA took no action. The process of trying to agree on an SSRS lasted nine months until the generic manufacturers applied to the FDA for separate REMS, which was granted. Reckitt Benckiser profited approximately $1 billion from the delay.

d) Citizen Petitions

Citizen petitions allow members of the public to formally request that the FDA take or refrain from taking administrative action.41 Citizen petitions, which must include the action requested and grounds, have historically been filed by branded drug makers, generic firms, and other interested stakeholders. FDA creates a docket for each petition filed and responds publicly to petitioner requests. Over the years, FDA has repeatedly, in its annual reports and testimony to Congress, discussed the increasing time spent on citizen petitions, backlogs, and potential for sham filings.Reference Buehler42 To address some of these concerns, Congress enacted 2007 amendments to the citizen petitions processes that added 505(q) as a petition category, requiring the FDA to respond to petitions within 180 days (now 150 days) unless further delay is necessary to protect the public health. Petition filers must certify that their petition is neither frivolous nor was intentionally delayed.43 Section 505(q) filings are most germane to generic entry delay, and constitute a sizable proportion of all citizen petition filings (e.g., 28% in 2013, 23% in 2015), and were filed by brand firms 92% of the time from 2011-2015.Reference Carrier and Minniti44 Nevertheless, 91% of 505(q) filings were denied from 2011-2015, and 39% were filed within 6 months of exclusivity expiration.45 FDA, moreover, resolved many of these petitions on the same day or very close to when it approved a generic, suggesting an interaction between the two decisions.Reference Feldman and Wang46 In short, the 2007 amendments seem to have had little impact on the number of petitions filed per year, and sham filings remain commonplace.Reference Carrier and Wander47

Reckitt Benckiser and related companies have filed several 505(q) citizen petitions related to their buprenorphine formulations. Perhaps the most controversial application filed by Reckitt Benckiser challenged approval of generic drug applications for Subutex and Suboxone tablets in 2012. In it, Reckitt Benckiser asked the FDA to refuse to approve generic applications unless they included targeted educational interventions to address the risk of accidental pediatric exposure and child tamper-resistant packaging, and also to delay approval until a decision was made regarding whether the brand-name tablets were discontinued for safety reasons.48 The FDA denied the petition, finding that REMS programs adequately mitigated pediatric harms and that the withdrawal of Suboxone tablets was not necessary for safety reasons — in effect, that Reckitt did not provide evidence that the product-hopped films reduced risks.49 The FDA referred this petition to the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to investigate for anti-competitive practices.50 In another petition, Monosol Rx asked the FDA to refuse to approve any buprenorphine/naloxone film generic application unless it referenced the Suboxone film new drug application and provided appropriate certification to all patents listed in relation thereto.51 The FDA denied this part of the petition because there could be some generic films in this category that are not pharmaceutically equivalent to Suboxone film.52

Reckitt Benckiser's cumulative anti-competitive actions served to secure Suboxone film's market dominance since 2012 and attracted a host of litigation challenges and investigations, as chronicled in Figure 2. Various generic companies challenged the film's exclusivity, resulting in agreement to extend exclusivity until 2023.53 In 2016, 36 states attorneys general sued the company for violating antitrust laws to extend the Suboxone monopoly by illegally product hopping and by delaying generic entry by engaging in REMS abuses and filing sham citizen petitions.54 Because the federal court failed to find Indivior legally responsible for the actions of its predecessor, Reckitt Benckiser, the case was dismissed in 2017.55 For its claims that Suboxone film was safer and less prone to abuse than less expensive generics, federal prosecutors in Virginia indicted Indivior for engaging in conspiracy and fraud.56 To resolve the FTC's aforementioned investigation of Reckitt Benckiser's actions along with the Department of Justice's concurrent investigation into the sales and marketing of Suboxone film, Reckitt Benckiser Group PLC agreed to a $1.4 billion settlement (Indivior is not party to this settlement and litigation against it remains ongoing).Reference Faulkner57 Although the company neglected to admit any fault, the settlement is the largest (as of the time of this writing) of any from a pharmaceutical company related to the opioid crisis.58 State Medicaid programs can choose to be a party to the agreement and receive funds to resolve any of their claims.59 While the evidence, publicity, and money forthcoming from the litigation and investigations can be helpful in paying for the costs of buprenorphine and mitigating some health harms, they do not seem to have deterred in any timely fashion Reckitt Benckiser's anti-competitive conduct nor prompted the company to admit liability.

In considering the obstacles to competition and socially damaging pricing conduct that is especially harmful for responding to the opioid crisis, we recommend regulatory and legislative changes. These would have more lasting effects in deterring brand firm behaviors that obstruct generic entry and elevate prices than litigation and drawn-out investigations. Suboxone is one egregious example of these types of abuses that have become commonplace in prescription drug markets. We suggest remedies focused on modernization of the Hatch-Waxman Act and altering FDA procedures — especially those related to REMS and citizen petitions.

III. Cost Implications of Suboxone's Market Dominance

The opioid epidemic has put enormous strain on public budgets. These stem significantly from cost of providing treatment for OUD. For instance, according to IQVIA data, Medicare and Medicaid accounted for 32% of the $2.58 billion in buprenorphine prescription sales in 2017 — a large proportion of which was for Suboxone. Strikingly, the high prices and elevated spending levels in this market that stress public and household budgets60 persist despite the fact that the patents on the main pharmaceutical ingredients have expired. The ability to extend exclusivity on Suboxone by impeding generic entry has raised those costs and generated substantial profits on the order of $1.6 billion for the company.61

Significant savings could have been realized had strong anti-competitive regulatory remedies been put in place in recent years. Using “yardsticks” based on the experience of similar drugs that did not experience the same types of barriers to generic entry as we have observed for Suboxone film, we estimate cost savings that could accrue from introducing generics into the Suboxone film market. Specifically, we conduct an event study for Subutex tablets that were subject to generic competition), assessing the actual price decreases associated with generic entry in this comparable market. We then use this percent decrease as an indication of the potential price responses to generic competition for the Suboxone film using data on buprenorphine sales. For these analyses, we use data from IQVIA for the years 2009-2017.

As previously discussed, Subutex tablets were subject to generic competition in late 2009 and were removed from market in 2011. The generic was then the only buprenorphine only tablet product on the market. A year after entry, the generic price was roughly 40% of the Subutex price on the generic launch date (or 60% below the pre-launch brand price). In regression analyses, estimated price declines of roughly 37% are attributable to generic competition.Reference Clemans-Cope, Epstein and Kenney62 This estimate is close to the very large literature on the impact of generic entry generally.63 Putting these results in the context of 2017 sales of Suboxone totaling $1.90 billion, savings of about 37% would amount to $703 million per year or $58.5 million per month. Data from Medicaid shows that in 2016 nearly $754 million was spent on buprenorphine, the vast majority of which was for Suboxone film. A 37% reduction in the price of Suboxone in the Medicaid market would relieve taxpayers of about $203 million for this single drug product.Reference Iyengar64

IV. Generic Drug Policy Reforms

In considering the obstacles to competition and socially damaging pricing conduct that is especially harmful for responding to the opioid crisis, we recommend regulatory and legislative changes. These would have more lasting effects in deterring brand firm behaviors that obstruct generic entry and elevate prices than litigation and drawn-out investigations. Suboxone is one egregious example of these types of abuses that have become commonplace in prescription drug markets.Reference Frank and Haffajee65 We suggest remedies focused on modernization of the Hatch-Waxman Act and altering FDA procedures — especially those related to REMS and citizen petitions.

a) Modernize the Hatch-Waxman Act

As discussed above, certain provisions of the Hatch-Waxman Act and its implementing regulations create opportunities for brand firms to delay generic entry by engaging in product hops that can stress public resources and hamper the affordability and accessibility of life-saving medications. Some such barriers have led to antitrust actions to address the potential harms that may result. However, this litigation route can be costly, lengthy, and produce uncertain outcomes.Reference Frank and Hartman66

First, we recommend legislation that directs the FDA to delist patents from the Orange Book that have been found to be invalid. Currently, the Hatch-Waxman Act requires that an ANDA filer identify any patents potentially relevant to their application. If the patent is listed in the Orange Book, the ANDA filer may certify that their application does not infringe on the patent or that the patent is not valid (so-called “Paragraph IV certification”). The Paragraph IV certification triggers a 45-day period for the originator firm to sue the generic ANDA filer; subsequent filing of a lawsuit triggers a 30-month stay on generic entry.67 Eliminating patents that have already been found to be invalid would, in a very simple way, eliminate one avenue to generic entry delays and would streamline the approval process. Indeed, the pending Lower Health Care Costs Act proposed by Sen. Lamar Alexander (R-TN) proposes to delist invalid patents and provide more transparency about patents listed in the Orange Book to reduce the potential for generic entry delay.68

Second, we suggest directing the FDA to request that a new drug application holder provide evidence of the incremental clinical value of a patent prior to granting exclusivity. The FDA would use that information to evaluate a patent prior to listing in the Orange Book. If the patent offered little or no incremental clinical value above products already listed, it would not be listed. Because it is typically the patent on the active pharmaceutical ingredient that loses protection in cases of line extension-product hops, failure to list the new product in the Orange Book may allow pharmacists to automatically substitute the generic product for the reformulated product. This could serve to eliminate reformulations offering few if any clinical benefits that are primarily designed to protect the brand name manufacturers from generic competition through the use of product hops. Requiring a showing of incremental value would have possibly prevented the Suboxone film from obtaining further exclusivity beyond Suboxone tablets. The FDA may, however, oppose such a proposal on the ground that it expands the agency's mission beyond traditional bounds by requiring them to develop frameworks for evaluating incremental value.

An alternative, third approach to addressing product hops would be to define a period before patent expiration and following generic entry when new formulations of an existing product could not be brought to market (although the new formulations could still be patented). Such periods could be for one year prior to patent expiration and one year post-generic entry, or some other period deemed reasonable to prevent artificial shifts to a new formulation. This approach would permit firms offering innovative new versions of existing products to bring those innovations to market and compete with extant products while greatly reducing the anti-competitive potential of reformulations connected to product hops. Such a step would have prevented Reckitt Benckiser from introducing Suboxone film shortly before Suboxone tablet patent expiration. Together these recommended changes should reduce unnecessary stays on generic entry, increase the likelihood that reformulations introduced to the market offer real clinical benefits if they serve to alter the competitive landscape, and facilitate more rigorous patent review.

b) Address REMS Abuses with the CREATES Act

The CREATES Act was originally proposed by Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-VT) in 2016 to address anti-competitive barriers to generic entry associated with obtaining bioequivalence samples and with the joint REMS requirement for bioequivalent products. The CREATES Act authorizes an eligible product developer to sue a drug product license holder, asserting that they failed to provide sufficient quantities of the product on commercially reasonable terms (i.e., at or below the most recent wholesale acquisition cost) to conduct bioequivalence or biosimilar testing.69 To win such a suit, the generic drug developer would have to establish by the weight of the evidence that the license holder withheld samples for 31 or more days post-request. A generic firm also could request that the FDA authorize them to obtain sufficient samples of a product subject to a REMS with ETASU, to clarify that the license holder will not be in violation of REMS if they cooperate. If a license holder violates these requirements, they can be required to provide the testing samples and also face monetary fines (up to the revenue earned during the delay period) plus litigation costs. The CREATES Act, moreover, establishes a separate REMS approval process for subsequent filers, so that an SSRS is not necessary.70

In sum, the CREATES Act provisions serve to undercut incentives of branded manufacturer license holders to withhold cooperation in providing samples or agreeing to a shared REMS program. The Act still preserves FDA's role in all safety reviews but allows FDA and/or the courts to have oversight and powers if brand firms are being uncooperative absent justified rationale. The threat of lawsuits with significant monetary penalties and modest burden of proof should deter brand firm delay tactics relevant to REMS to a significant degree.

c) Modify Citizen Petition Filing Procedures

FDA is actively reviewing the citizen petition process and recently issued draft guidance in October 2018 to describe factors it will consider in determining whether a 505(q) petition was submitted primarily for the purpose of delaying the approval of a general drug application.71 If these factors are met, the FDA is justified to invoke it's statutorily delegated power to summarily deny a citizen petition.72 Thus far, the FDA has never invoked this power, perhaps because the statutory standard is too high (in that the petition must have been filed for the “primary purpose” of delaying, and the petition cannot “on its face raise valid scientific or regulatory concerns”).73 Even if the new guidance is finalized, it will neither address this high statutory standard, nor be legally binding, nor go far enough to deter citizen petition abuses in an enforceable, prescriptive way that would bring about more meaningful change. We propose four stronger actions that could be taken by Congress (or potentially FDA rulemaking processes) to stop citizen petition abuses engaged in by brand firms to hinder generic entry, including in the opioid treatment context.

First, brand firms could be more readily and easily penalized for filing sham 505(q) citizen petitions. Parties deemed to have engaged in behavior designed to block or delay generic entry via a citizen petition could be subject to punitive measures, potentially up to the amount of profits earned during the period of delay (i.e., since the filing) suggesting that new approaches are needed.74 At present, antitrust liability only attaches if the government determines a petition is a “sham” both based on objective and subjective standards under the Noerr-Pennington doctrine. So a lower evidentiary bar and shorter timeline to resolution are preferred. Legislation would incorporate explicit penalties and perhaps require only objective determination that a filing is a sham.Reference Evans75

Second, implementing procedural barriers to 505(q) citizen petition filings could deter sham and delay-motivated filings. For example, legislation or an FDA rule could require that 505(q) petitions be filed within a year of when a generic company files an ANDA and/or that no more than one filing be made by the same petitioner related to the same drug during a certain time period (e.g., a year).76 As well, generic filings could move forward on a timeline unrelated to 505(q) filings, such that an ANDA could be approved in advance before a relevant 505(q) decision is made. Of course, if filings do raise legitimate concerns, then all of these procedural barriers to 505(q) filings or delays could prove harmful to the public's health. Nevertheless, increased post-marketing surveillance and REMS programs associated with approved products provide some assurances that harms will be mitigated post-approval. Moreover, the FDA has itself stated that it is “very rare that petitions present new issues that [FDA] has not fully considered,” and that “very few of these petitions on generic drug matters have presented data or analyses that significantly altered FDA's policies.”Reference Buehler77

Third, brand firm competitors who raise concerns over their own product's characteristics as a part of the 505(q) filing — as was the case with the Reckitt Benckiser filing — could be estopped from continuing to market and sell their product in this form.78 In many cases, brand firms will already have engaged in product hops in anticipation of generic ANDAs, but this move could deter some instances of sham filings if profits are at stake.

Fourth and finally, Congress could further empower FDA to invoke its summary disposition power to deny petitions filed primarily for the purposes of delaying generic approval.79 Removing the “primary” purpose and “on its face” language from the statute could lower the threshold for FDA to summarily deny petitions.Reference Carrier80 Legislation could also shift the inquiry into filing timing, whereby late-filed petitions are presumed to be per se shams. These combined actions could deter significantly sham citizen petitions, like the ones filed by Reckitt Benckiser to delay generic entry in favor of Suboxone film dominance.

V. Conclusions

We have highlighted some egregious brand firm anticompetitive tactics employed to extend market exclusivity. Addiction treatment need during the opioid crisis gives special urgency to reform these types of market abuses that contribute to higher drug prices and have cost society close to $1 billion. Moreover, because these behaviors are widespread beyond the buprenorphine market, they warrant comprehensive reform.

We have thus recommended additional steps to more comprehensively address abuses, namely statutory changes to the Hatch-Waxman Act and modifications to FDA regulatory procedures. Regarding all the proposals advanced, penalties levied for engaging in delay tactics must be sufficient to deter anti-competitive practices, as compared to the costs incurred by firms by engaging in the practice. In addition, closing one regulatory loophole could incentivize brand firms to seek and utilize others, so a carefully constructed regulatory regime is needed to deter anti-competitive behavior and enhance social welfare in the buprenorphine market and beyond.

Acknowledgement

Dr. Haffajee and Dr. Frank's work on this article was supported by funding from the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.