In August 1624, a public court held in Gillingham, a small town bordering the royal forest of Gillingham in north Dorset, was presided over by commissioners from the court of exchequer, who had travelled from London to obtain local tenants' consent to the proposed enclosure of Gillingham Forest.Footnote 1 Gillingham was the first royal forest to be subjected to formal legal proceedings of ‘disafforestation’ by James VI and I's heir, Prince Charles.Footnote 2 Hitherto, the forest had lain under the jurisdiction of ancient forest laws maintaining royal hunting grounds, while neighbouring tenants exercised broad customary rights. Disafforestation abolished both forest laws and commons, allowing royal forests to be enclosed and transformed into exclusive property to be leased at a profit. On his accession to the throne in 1625, Charles I extended disafforestation to royal forests across England in one of the first major projects of state-sanctioned enclosure and ‘improvement’ of ‘waste’ commons.Footnote 3

Pre-eminent among the commissioners at the Gillingham court was the surveyor-general of the exchequer, Sir Thomas Fanshawe, who gave impetus to parallel crown projects of disafforestation and Fenland drainage from the mid-1620s.Footnote 4 Fanshawe's pivotal presiding role was spatially signified by sitting ‘up on high’ on ‘a bench above the rest’ of the commissioners, including Scottish courtier and royal favourite, Sir James Fullerton, who had been granted the future lease of the enclosed forest.Footnote 5 At the court, a surveyor named Thomas Jenkins displayed and described a detailed map drafted under Fanshawe's instruction, which delineated the boundaries of the intended enclosure to assembled tenants (Figure 1).Footnote 6 Jenkins's map drew on newly empirical cartographic perspectives to render the forest both legible and profitable.Footnote 7 Overlapping, and often conflicting, rival claims by commoners and crown to soil, grazing, game, and wood, which had formerly governed forest property rights, were now visibly erased and the crown's right to enclose its possession asserted.

Fig. 1. A section of Jenkins's map, entitled ‘The plot of ye whole extent of ye Forrest of Gillingham in ye County of Dors[e]t as well of ye waists of ye said forr[est] as of all ye other severall farmes & grovndes lying w[i]thin ye same, as it was taken before ye deafordstation thereof, Anno Dom 1624’. Dorset History Centre, D.1366/1.

For their part, however, the assembled tenants ‘refused to beleeve it to be a true plott or mapp unless the said Jenkins would afirme it upon his oath to be good’.Footnote 8 The tenants' knowledge of the forest was not founded in empirical measurement or schematic oversight, but direct experience, collective use, and intergenerational memory. Perceptual disjunction between cartographic representations of the forest and the commoners' use-based knowledge could thus be bridged only by an oral pledge of honesty. Having secured Jenkins's word, the tenants present – predominantly propertied ‘lawfull’ commoners – signified their consent by ‘subscribing’ to the map.Footnote 9 Meanwhile, the significant numbers of poor cottagers who dwelt near Gillingham Forest were conspicuous by their absence. Since the exchequer did not recognize their unsanctioned common rights, the cottagers were excluded from elaborate legal processes of consent and compensation.Footnote 10

The tenants' mistrust was prescient: an ensuing legal dispute heard in the exchequer in 1626–7 hinged on whether Jenkins's description of the map at the 1624 court had included 1,000 acres known as ‘Bailiff's Walk’.Footnote 11 The commoners subsequently claimed that it had not and that, had it been included, they would ‘never have consented’ to its enclosure, since it was a separate common belonging to Gillingham Manor.Footnote 12 The crown, however, asserted that Bailiff's Walk was included in both the forest and its cartographic representation, and could thus be lawfully enclosed. The exchequer ultimately found in the crown's favour on the basis of its superior documentary proof.Footnote 13 Alongside ancient documents, Jenkins's ‘fair mapp’ was cited as conclusive evidence, as was the ‘paper booke’ recording the commoners’ consent.Footnote 14 By contrast, elderly witnesses who attested to Gillingham tenants’ immemorial rights in Bailiff's Walk were deemed unreliable. The resultant decree dismissively noted that the litigants ‘did offer noe other proofe then…[their] conceite in their said answeares that the bounde of the said forrest should not include the said Bailyffe walke’.Footnote 15 Processes of mapping therefore involved an enclosure of epistemic authority by specialized surveyors and their patrons, superseding collective memory wherein customary rights were founded and allowing the landscape to be redrawn.Footnote 16

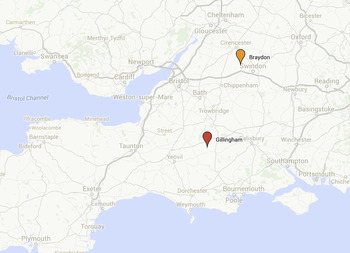

The dispute, however, was not resolved by the central court's judgement at Westminster. In Dorset, a cacophony of popular grievances erupted when Jenkins attempted to divide Bailiff's Walk, resulting in several separate court cases centring on the inaccuracy, unfairness, and unilateralism of his schematic partition.Footnote 17 Concurrently, the landless poor, rendered legally voiceless, expressed unequivocal riotous dissent as Fullerton's workmen ‘enter'd and endeavour'd to inclose and improve’ the forest in the winter of 1626–7, followed by well-documented ‘inormous riotts’ in 1628.Footnote 18 Hundreds of commoners united to level fences, uproot newly planted crops, appropriate deer and wood, and attack workmen, local officials, and Star Chamber messengers. In physically un-mapping exclusive boundaries, the ‘unfencers of Gillingham’ transformed the forest into an arena of contestation in which customary notions of right were spatially articulated.Footnote 19 Furthermore, Gillingham became the first of a wave of disafforestations in western England that provoked widespread unrest in the late 1620s and early 1630s.Footnote 20 Just fifty miles north of Gillingham, for example, Braydon Forest in Wiltshire was subjected to parallel disafforestation proceedings instigated by Fanshawe in late July 1626, which provoked analogous large-scale riots during the summer of 1631 (Figure 2).Footnote 21

Fig. 2. A map of south-west England showing Gillingham Forest, in Dorset, and Braydon Forest, in Wiltshire. © 2016 Google.

I

Originally synonymous with increasing land revenues by enclosure and other means, ‘improvement’ has often been regarded as a material process falling squarely within social history's ambit.Footnote 22 By the seventeenth century, however, improvement also became associated with an emerging discourse advocating the application of ‘industrie’ and ingenuity to the intensive and profitable exploitation of the natural world. This discourse has received concerted attention from scholars such as Richard Hoyle, Andrew McCrae, and, most recently, Paul Slack, who argues for the seventeenth-century emergence of a unique English culture of improvement which proved fundamental to its subsequent economic ascendancy.Footnote 23 Dialogue between printed ideas and practices of improvement on the ground, however, remains underexplored. This article challenges readings of ‘improvement’ that are confined to a literate, elite sphere, thus taking printed claims of ‘economic betterment’ at face value and bestowing brief mention on ‘losers’ as a regrettable, but necessary, consequence of progress.Footnote 24 Improvement was not simply a triumphal narrative of advancement, as articulated in print, but rather was forged in active conflicts within the landscape as newer perspectives clashed with older legitimating notions. In considering royal forests as sites in which central improving ways of seeing and using the landscape collided with local customary ones, this article seeks to bridge ossified frontiers between social and intellectual history.

Early Stuart surveyors became active agents of both discourses and practices of improvement in harnessing their empirical perspectives to the transformation of the landscape. They thus elude rigid disciplinary boundaries. This amphibious professional class of propagandists and practitioners elaborated geometric techniques and improving principles in print, lobbied the exchequer for patronage in private, and actively reshaped the landscape in scale maps and surveys.Footnote 25 Surveyors claimed to improve the world through instruction in techniques of empirical measurement and cultivation, binding knowledge to labour and ideas to action in their tracts. In the 1610s, for example, crown surveyors John Norden and Rocke Churche published treatises bringing a didactic ‘surveyor’ into pedagogical dialogue with sceptical and ignorant characters representing the agrarian social hierarchy, variously berating, persuading, and instructing.Footnote 26 Simultaneously, mathematicians Aaron Rathborne and Arthur Hopton adopted a schematic presentation of geometric surveying techniques in manuals addressed to patrons, surveyors, and ‘mathematicall practizer[s]’.Footnote 27 If surveying texts took the landscape as their primary subject, however, it has tended to remain an inert backdrop in much scholarship. As this article shows, examination of surveyors’ spatial and social processes of measurement, mapping, and improvement during disafforestation provides an important corrective, revealing the ambiguous application of empirical principles within forest landscapes.

Moreover, royal forests were not tabula rasa onto which improving ideals could be writ large: they were inhabited. In attempting to recast forest commons in line with its fiscal intentions, the crown provoked mass unrest. Viewed retrospectively, enclosure riots have often been presented as reflexive, apolitical responses to need. Roger Manning, for example, described the motives of those involved in early modern disorder as ‘devoid of political consciousness’ and thus contended that ‘anti-enclosure riots may be regarded as displaying primitive or pre-political behaviour’.Footnote 28 More recently, scholars such as Keith Wrightson, Steve Hindle, and Andy Wood have constructed a more expansive definition of ‘the political’ to encompass the politics of everyday life and parochial power relations, interpreting gesture and speech as acts of deference and defiance.Footnote 29 Wood, in particular, has identified legal depositions – witnesses’ oral testimonies recorded by court scribes – as a rich source of plebeian political ideas, which constitute ‘speech acts’ of equal significance to those discoverable in surveyors’ texts.Footnote 30 These testimonies were fundamentally mediated by leading questions and legal codes of legitimacy as ‘deponents’ were called before exchequer commissioners to answer ‘interrogatories’ drawn up by complainants and defendants alike. Nevertheless, 124 individual depositions produced in nine exchequer cases between 1627 and 1637 illuminate the litigious contestation of exclusive boundaries by customary perspectives during disafforestation in Gillingham and Braydon.Footnote 31 If speech acted as a weapon in enclosure disputes, acts could also speak: putting up or throwing down fences, for example, involved the spatial articulation of political ideas.Footnote 32 Whilst ‘lawfull’ commoners – consenting but discontented – were given legal voice during disafforestation, the landless poor used riot as a performative language through which they collectively resisted the imposition of rationalized private property by dis-ordering the forest. It is not possible to examine rioters’ defences as very little material survives from Star Chamber prosecutions. However, the customary logic and popular legitimacy of their acts is discoverable by reading against the grain of alarmed correspondence between privy councillors and local officials, which denounced rioters as acting ‘in contempt of all authority’.Footnote 33

The conflicts that convulsed Gillingham and Braydon Forests demonstrate how different ways of knowing the landscape became implicated in its disputed transformation through enclosure. As the French theorist Henri Lefebvre influentially argued, ‘space’ is both socially produced and in itself productive of social relations.Footnote 34 It thus constitutes a site of both hegemony and agency, through which authority is coded, lived experience structured, relations of production reproduced, and social practices signified and symbolized. More recently, the landscape has been examined as a ‘lived environment’ and ‘means of conceptual ordering that stresses relations’, while Adam Smith has called for ‘an account of the constitution of authority in the production of landscapes’.Footnote 35 This article develops such insights to argue that not only were early modern landscapes socially constituted, but ways of seeing and knowing landscapes also supplied critical means by which spatialized social relations were produced, reproduced, defended, and transformed. Methodologically, these ways of knowing may be best understood as ‘epistemologies’, akin to the Foucauldian ‘episteme’ or J. G. A. Pocock's adaptation of Thomas Kuhn's concept of the ‘paradigm’ to the history of political thought, whereby certain linguistic and intellectual structures ‘authoritatively determine the patterns in which men think’.Footnote 36

Critically, however, seventeenth-century disafforestation reveals the negotiation of contesting epistemologies of landscape – cartographic and customary – at the cusp of agrarian capitalism and thereby challenges monolithic accounts of epistemology by reintroducing agency. Surveyors’ rationalized epistemology facilitated attempts to inscribe the crown's fiscal and political imperatives on both ‘waste’ land and ‘idle’ inhabitants through enclosure. Political theorist James Scott has described this process as one of ‘legibility’, arguing that the ‘cadastral’ perspectives of the modern state have been critical to its ability to grid power onto territories and subjects.Footnote 37 Both in print and practice, early seventeenth-century surveyors constructed new ways of seeing and using land, yoking empirical knowledge to exclusive ownership so that each might ‘know and have his own’.Footnote 38 In rendering royal forests subject to central oversight and intentions, surveyors became architects of a radical reconfiguration of social relations mapped across them. Meanwhile, customary praxis, rooted in collective use and ancient memory, was intimately related to both reproduction and defence of forest commons. Unlike the distanced, empirical observations of surveyors, custom was ‘never fact. It was ambience’; or, as jurist Sir Edward Coke explained in 1641, ‘custom…lies upon the land’.Footnote 39 During disafforestation, customary notions of right were mobilized within both central courts and forest landscapes, directly challenging new boundaries and perspectives. Neat polarities, however, risk obscuring ambiguous interactions. Forms of social credibility, like oaths, could bridge customary and empirical epistemologies, while, in practice, surveyors relied on tenants’ experiential knowledge, alongside new measuring techniques, to map landscapes. Even while seeking to ‘improve’ and transform the landscape, surveyors attempted to address popular censure of their ‘art’ by integrating it into ideals of ‘commonwealth’. Failure to achieve this reconciliation was, however, confirmed by the profound conflicts provoked by disafforestation projects.

Via the framing concept of ‘epistemology’, this article examines improvement as a process in which different ways of knowing and using the landscape became pivotal to the production, contestation, and reconfiguration of spatial social relations mapped across early modern landscapes. This article will first examine the emergence of an increasingly assertive and expansive customary praxis amongst forest commoners, in which collective use, memory, and landscape were intimately entwined and forests were rendered increasingly illegible and unprofitable to the crown. It then turns to consider the ambiguous processes by which surveyors’ empirical lens was applied to crown attempts to ‘improve’ royal forests into alienable and profitable property through disafforestation. Finally, it contends that improvement ‘on the ground’ was a fundamentally contested process, in which commoners collectively challenged exclusive boundaries first drawn in surveyors’ maps through both riotous and litigious articulations of customary notions of right.

II

[N]ow the wood is all gone, the soyle turned to a common, and the rent quite lost, and not any paid: and truly more is like to follow in this kind, if the headie and headlong clamour of the vulgar sort be not…moderated.Footnote 40

Writing in 1612, Rocke Churche expressed a concern common to surveyors and statesmen that crown lands had escaped royal oversight to the advantage of an increasingly assertive tenantry. Historically, the crown's relationship to its landholdings and tenants was mediated by a bewildering constellation of localized officers, courts, and customs that governed complex bonds of reciprocal rights and duties. For manorial lords, loyalty, services, and profit could be extracted from the tenantry through rents, fines, and heriots, whilst for tenants, significant control over land and resources was secured. According to Edward Thompson, custom thus constituted a site of struggle, concerning ‘exploitation and resistance to exploitation…relations of power which are masked by the rituals of paternalism and deference’.Footnote 41 As land and its products became increasingly valuable with the emergence of national commodity and land markets, the customary status quo became increasingly advantageous to the tenantry as rents and fines remained fixed at low values. Moreover, in the absence of effective manorial supervision, tenants were often accused of taking broad liberties with the land's resources by ‘colour’ of ‘p[re]tended’ customs.Footnote 42 In 1610, for example, Norden complained that ‘in late dayes tennants stand in higher conceites of their freedome then in former times’.Footnote 43 Elsewhere, in numerous memoranda addressed to the exchequer, surveyors complained that the crown's rightful prerogative and profit had been ‘usurped’ by corrupt local officers and unruly tenants through ‘concealment’ of lands, unsanctioned common rights, unpaid and stagnating rents and fines, and pilfering and sale of wood and other resources.Footnote 44 As an absentee landlord with diverse lands managed on its behalf, the crown was deemed particularly vulnerable to such transgressions, which were ‘the common cloake of mischiefe used most in the Kings land’.Footnote 45

Royal forests were identified as amongst the most illegible and unprofitable of crown lands. Established as hunting grounds in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries for the Plantagenet crown, forest laws to preserve ‘venison’ and ‘vert’ were implemented by an array of forest officials and specialized courts, and were initially resisted as an oppressive imposition.Footnote 46 During the sixteenth century, however, royal authority waned in many forests as courts met with decreasing frequency and officials became increasingly corrupt.Footnote 47 In western England, commoners in Braydon and Gillingham thus turned forest customs to their advantage by claiming extensive rights, whilst growing numbers of landless cottagers relied on informal common rights for subsistence. Containing over 4,000 acres apiece, Gillingham and Braydon forests were ‘intercommoned’ by thousands of inhabitants from bordering towns, manors, hamlets, and villages who exercised sanctioned grazing rights, as well as illicit wood gathering and game poaching.Footnote 48 In the seventeenth century, the term ‘intercommon’ straightforwardly denoted the practice of sharing a common amongst different manors, but also, less tangibly, having relations with others, or mutually sharing and participating.Footnote 49 Forest commoners intercommoned in both senses, sharing a collective space governed by a multiplicity of overlapping practices that fostered communal identities both within and beyond manorial and parochial boundaries.Footnote 50 The annual springtime hunt of Cricklade Saint-Sampson parish in Braydon, for example, was a ‘usage and custome’, with the kill given to ‘a merry meeting of the neighbours’ at the parish church.Footnote 51 Frontiers between sanctioned and illicit commoning could, however, be unstable. Similar celebratory hunts in Gillingham on New Year's Day and summer solstice were decried as illegal transgressions of royal authority, and hunters from Gillingham were summoned before the Star Chamber in November 1624, accused of conspiring to ‘riotously…hunt and kill’ royal deer.Footnote 52 Custom could therefore be both a locus of communal cohesion and conflict. While the crown technically owned soil, timber, and game in both forests, it contended with a complex web of customary claims to natural resources. Following inaction from forest officials, several unsuccessful exchequer commissions were issued to identify and punish offenders during the 1610s.Footnote 53 In 1611, for instance, a commission in Braydon found ‘manie great spoiles, wastes and distructions’ committed ‘for the most part by poore people dwellinge near[by]…& also by our keepers’.Footnote 54 Fiscal administrators and surveyors increasingly condemned such practices as ‘both a custome and an abuse’, thereby collapsing distinctions between the two.Footnote 55

From the crown's perspective, the landscape was therefore a site of central authority and profit in which tenants’ assertive claims constituted a threat ‘not onely to a mannor…but to a whole common-wealth’.Footnote 56 In attempting to reassert its command, however, the crown was confronted by the illegibility of uncodified, unwritten local customs, which were founded in a system of epistemological authority vested in direct experience and intergenerational oral transmission. Advantage was thus conferred on commoners who constituted the collective repository of memory, and local customary practices constantly eluded elite legal definitions of custom. A fundamental epistemological distinction between central law and local custom was elucidated in 1612 by Sir John Davies, a pre-eminent lawyer and administrator of Irish plantation:

[A] custome which hath obtained the force of a law, is always said to be jus non scriptum: for it cannot be made or created either by charter, or by parliament, which are acts reduced to writing, and are alwaies matter of record; but being onely matter of fact, and consisting in use and practice, it can be recorded and registered no-where but in the memory of the people.Footnote 57

This disjunction was evident during disafforestation, where the exchequer differentiated broad use-rights claimed by commoners along narrow property-based lines.Footnote 58 A sharp distinction was drawn between use and right, dividing ‘lawfull comoners’, whose rights depended on their tenured status as manorial copyholders and freeholders, from landless cottagers, described as those ‘who had noe right of common at all but yet had used to common’.Footnote 59 The short shrift accorded to use-rights contrasted with the primacy claimed for the crown's legal ownership, which was invoked to support enclosure.Footnote 60

Customary practices in Braydon and Gillingham defied official definitions, encompassing both sanctioned and illicit customs. Forest commoners testifying in the exchequer often spoke of ‘right, custome and usage’ as an indivisible Trinity to describe their use-rights.Footnote 61 Translation of the static legal entity of ‘common rights’ into the verb ‘comoning’ by several deponents attested to the active quality of such rights as a constitutive social process founded in practice.Footnote 62 Thomas Trinder, for example, constructed inalienable rights from practice by asserting a ‘libertie and fre[e]dom of comoninge’, while an expansive and assertive vocabulary described common rights ‘over all the forrest’ in an ‘ample and large mann[er]’ and ‘at all tymes at theire pleasure’.Footnote 63 Forest commoners further distinguished the crown's legal prerogatives from their own use-rights, with the former accorded secondary significance. Numerous Braydon commoners emphasized that, although the crown owned the ‘soile’ of the forest, ‘the king hath had noe other use thereof but feeding for his deare, [and] making and felling and selling of coppices and other trees’.Footnote 64 Unequivocal assertions of right to ‘theire comon’ therefore stood in variance to elite legal interpretations of ownership.Footnote 65 Drawing on his experience of surveying royal forests, Churche, for example, denounced those tenants who ‘with a generall clamor…crie for their common, their common…as though the common were their owne inheritance’.Footnote 66 For many commoners, forest courts’ official sanction was ancillary to the autonomous legitimacy of their customary rights, confirming, rather than bestowing, de facto rights exercised and founded in practice. As one elderly yeoman, Henry Rutter, stated, rights exercised in Braydon had ‘allso’ been ‘ratified’ and ‘allowed of’ at Justice Seats and Swanimote Courts.Footnote 67

As recently and forcefully demonstrated by Wood, memory of ancient, unbroken use held distinctive status within customary culture as a collective repository of authoritative knowledge that could be invoked for legitimation.Footnote 68 Christopher Gabbet, an old man himself, substantiated his account of the boundaries of Little Chelworth Manor by referring to ‘the gen[e]rall reputac[i]on of all the countrey since his memorye and that hee hathe often heard many oulde men saye the same’.Footnote 69 The predominantly elderly deponents reinforced claims that the ‘comon have bine soe used…tyme out of mynde’ by appealing to the oral transmission of knowledge from their ancestors.Footnote 70 Aged sixty, one Braydon commoner, William Messenger, verified his customary claims by invoking intergenerational memory spanning a century, since his centenarian father ‘well knew the same’.Footnote 71 Within customary epistemology, the burden of proof was notably negative, with absence of dissent taken as evidence of unbroken practice. Witnesses therefore emphasized that rights had been exercised ‘without any gane sayinge’, ‘contradicc[i]on’, or ‘denyall’.Footnote 72

A vital method of transmitting customary knowledge about the landscape was the iterative ritual of ‘perambulation’, which involved collectively walking the ancient boundaries of commons, manor, or parish, and thereby spatially inscribing customary rights within inhabitants’ memories.Footnote 73 Such knowledge was vested in the memories of elderly men and, quite literally, beaten into the youngest boys, who were often whipped at significant landmarks to impress the memory indelibly.Footnote 74 The earliest recorded perambulations of Gillingham and Braydon Forests dated to 1300.Footnote 75 During the Braydon disafforestation, forest officer Thomas Sadler recited detailed boundaries by memory, recalling a 1608 perambulation when the Justice Eyre had commanded officers to meet at a ‘bound m[a]rke’ called Charnam Oak and ‘call unto them all the competent men’ residing nearby.Footnote 76 As late as 1733, the boundaries of Purton parish, which bordered Braydon, were perambulated using landmarks including ancient oaks surviving from the former forest. At each oak, ‘a gospel was read and crosse made & money thrown amongst the boys and to every person there present were given cakes & ale’.Footnote 77 In this way, forest rights were rooted in a customary epistemology in which memory, experience, and landscape were interwoven and perpetuated by ritual.

By the 1620s, custom's elastic boundaries had also stretched to incorporate informal use-rights exercised by significant numbers of poor landless cottagers around both forests. In Braydon, poor commoners appear to have been predominantly ‘outsiders’, displaced from native parishes by population growth and agrarian change, who erected unsanctioned cottages on ‘wastes’ bordering the forest.Footnote 78 In Gillingham, however, Buchanan Sharp has suggested that the persistence of local surnames and evidence of increasing numbers of poor cottagers within the manorial structure itself were indicative of local population growth.Footnote 79 Homegrown or otherwise, the poor relied on the forest commons as an essential element of their ‘make-shift’ subsistence economy.Footnote 80 While the local broadcloth industry in Gillingham furnished the poor with a sporadic income source, there was little wage labour in Braydon, resulting in greater reliance on both commons and poor relief for subsistence.Footnote 81 Prominent Braydon gentleman, Anthony Hungerford, thus reported that ‘many hundred of poore people (having comon of pasture there) are wholye supported and relieved’ by the forest commons.Footnote 82

The legitimizing discourse of use-rights conferred value on differential need among those using forest resources, encompassing ‘strangers’ and ‘poor’ alongside crown and commoners. In Gillingham, potential ‘stoppage’ of public highways by enclosure was deemed ‘verie noysome to travelers’, hindering the large cattle ‘dryftes’ passing through the forest from Wales and Ireland, but would ‘tend to the undoeing and baggeringe’ of local inhabitants who daily used the highways.Footnote 83 Likewise, it was overtly recognized that disafforestation disproportionately penalized the poor. In Braydon, deponents testified that disafforestation would be ‘p[re]judiciall’ to manorial lords and ‘to the greate hurt’ of tenants, but to ‘the utter undoeing of many thowsand of poore people that nowe have right of comon…and doe live thereby’.Footnote 84 Whilst the adverb ‘nowe’ suggested the recent acquisition of such rights, it also indicated an expansive discourse of custom as a living body of rights founded in use and need that were constantly negotiated and imperceptibly evolving.

III

Surveyors’ empirical perspectives were presented as the antidote to tenants’ assertive claims and the corresponding illegibility and unprofitability of the landscape. The epigraph of Rathborne's The surveyor (1616), aptly dedicated to the young Prince Charles, typified surveying literature in promising to re-establish central command over territories and subjects. Following the sixteenth-century rediscovery and translation of classical cartographers and geometricians such as Euclid, Pythagoras, and Ptolemy, surveyors actively adapted their insights to construct an empirical science of surveying (Figure 3).Footnote 86 Purveyors of this ‘upstart art found out of late’ invented complex instruments such as ‘theodolites’ and developed new geometric techniques for drawing ‘scale’ maps and valuing land in standardized units, both spatial and monetary.Footnote 87 In doing so, surveyors claimed an inherent justice for their accurate perspectives and thus constructed epistemological truth claims that superseded custom's authority over the landscape. As one surveyor, William Folkingham, argued, ‘[t]ake away number, weight, measure, you exile justice, and reduce and haile-up from hell the olde and odious chaos of confusion’.Footnote 88 Amidst ‘great ignorance’ of crown estates, surveyors promoted their empirical lens as a means by which the chaotic customary landscape might be untangled and redrawn to promote landlords’ fiscal intentions.Footnote 89

Fig. 3. Frontispiece of Aaron Rathborne's The surveyor in foure bookes (1616). The allegorical figures of Arithmetica and Geometria represent two columns of knowledge, respectively bearing aloft celestial and terrestrial globes. The Latin inscription reads ‘Hide not treasures and talents in the field’. In the upper panel, the skilled surveyor uses an azimuth theodolite, the most complex contemporary surveying instrument, trampling two figures of folkloric appearance underfoot. The bottom panel depicts an ‘ignorant’ surveyor ‘abusing’ the basic tool of the plane table and recounting to credulous tenants ‘what rare feats they can perform’. © The British Library Board: 528.n.20.(2.).

By 1600, surveyors had emerged as a vocal profession with reforming zeal. Norden described surveyors’ ‘bils fixed to posts in the [London] streets, to solicite men to afford them some service’, while a proliferation of didactic treatises sought to articulate surveyors’ professional standards, provide practical instruction, and secure patronage.Footnote 90 Less publicly, surveyors such as Radulph Agas and Sir Robert Johnson successfully lobbied the exchequer to utilize their services in preventing ‘abuses’ and improving revenues on crown estates.Footnote 91 As one anonymous manuscript tract, penned in 1606, urged, only by ‘exact and perfect surveys’ could the exchequer be ‘trulie acquainted with how his Ma[jes]tie is used or abused in his highness profit or prerogative by comon p[er]sons’.Footnote 92 Successive lord treasurers heeded such appeals and sought to establish an unprecedented central body of information to aid improvement of crown lands and revenues. Some 125 surveyors were deployed at a cost of over £20,000 to undertake extensive surveys of crown estates, which were consolidated by Robert Cecil, earl of Salisbury, on his appointment as lord treasurer in 1608.Footnote 93 Salisbury's successors, however, lacked the improving vision necessary to capitalize on earlier investments through extensive estate reform and tended instead to favour more immediately profitable sales of land and timber.Footnote 94

Not until Charles I's accession to the throne did surveyors become central facilitators of royal policies, harnessing their empirical epistemology to the improvement of ‘waste’ forests and fens. From 1612, the young prince of Wales had acted as a key patron to surveyors, including Norden in the duchy of Cornwall and Fanshawe as his surveyor-general.Footnote 95 Following Charles I's dissolution of parliament in 1626 without securing critical fiscal grants, the privy council investigated alternative means of raising revenue, including a central proposal concerning improvement of royal forests.Footnote 96 Although his venatory father had explicitly opposed disafforestation, Charles consented to enclosure of forty-eight of sixty-six forests on Fanshawe's urging.Footnote 97 Earlier exchequer attempts to render royal forests profitable in the 1610s had relied on intensified customary exploitation by levying fines under forest laws, while disafforestation promised to denude them entirely of the unprofitable tangle of customary relations in order to convert them into alienable property. A Gillingham disafforestation decree thus recounted that Charles I had settled on improvement as a solution to ‘the div[e]rse spoyles and decaye of the woods and game’ by those who ‘claymed or pretended to have right of common’.Footnote 98 Disafforestation instituted relations of emergent agrarian capitalism, typified by Leigh Shaw-Taylor as ‘a tripartite social structure’ in which most land was owned by large landowners, rented to large capitalist tenant farmers, and cultivated by agrarian labourers.Footnote 99 The crown's recognition of the profitable potential of ‘progressive economic activity and rationalization’ thus converged with a ‘new cultural climate, rationalistic, empirical, pragmatic’ as surveyors’ techniques were deployed in the improvement of royal forests from the mid-1620s.Footnote 100

In the realm of print, surveyors actively forged connections between empirical measurement, enclosure, and profit via a discourse of improvement. If, as Slack has recently argued, improvement was indisputably a ‘word essential to political discussion of national affairs and an integral part of English culture’ by 1700, a century earlier surveyors and agricultural writers were energetically reworking the terms of ‘commonwealth’ to incorporate improving ideals.Footnote 101 This involved the metaphorical extension of ‘improvement’ from its earlier synonymous relationship with enclosure to encompass a nexus of interconnected principles, including empirical knowledge, intensive cultivation, and maximal profit, which intersected with Baconian empiricism and Hartlibean reformation.Footnote 102 For proselytizing surveyors, their skills formed an applied ‘science’ with improving intent, whereby lessons ‘suckt from famous geometrie’ were directed toward ‘such needful workes that much may profit you’.Footnote 103 As a prolific author of devotional tracts as well as surveyor, Norden challenged moral suspicion of untrammelled profit by establishing ‘increase of earthly revenues’ as a godly duty fundamental to the commonwealth.Footnote 104 Since the Fall, Norden argued, ‘our originall disobedience’ had condemned man to improve the world through application of industrious labour and empirical knowledge – ‘new diligence, and new arte’ – by which the twin vices of ‘ignorance and idlenesse’ were to be overcome.Footnote 105 Improving tracts thus instructed in techniques of cultivation and measurement by which land ‘may be bettered, reformed and amended’.Footnote 106 It is no coincidence that the first tracts of surveying and husbandry were published as companion volumes in 1523: both were applied and improving sciences founded in observation, categorization, experimentation, and experience.Footnote 107 Norden applied a Baconian framework to establish surveyors as central facilitators of improvement, since ‘to preserve or augment revenues, there must be meanes: the meanes are wrought by knowledge’.Footnote 108 In private, he was more direct, promising to ‘y[i]eld his Ma[jes]t[y] a great revenew’ through accurate survey.Footnote 109

Diametrically opposed to cultivation and profit were the ‘wild and ruinous’ commons in which the ungodly state of ‘universall wildernesse’ that characterized early ‘great Britain’ persisted.Footnote 110 Foreshadowing Garrett Hardin's theory of ‘the tragedy of the commons’ by several centuries, Churche insisted that the communal nature of ‘miserable bare’ commons resulted in ‘neither pleasure nor certaintie of gaine’, whereas once divided ‘every man might know his own, and dispose thereof as he should think good for his best profit’.Footnote 111 Only exclusive property, Churche implied, could provide necessary incentives to industrious improvement. Surveyors, commentators, and statesmen alike thereby began to separate enclosure from the ‘cankers’ of depopulation and engrossment, arguing that to condemn enclosure was akin to ‘beating Jacke for Jills fault’.Footnote 112 Enclosure was instead yoked to virtues of industrious cultivation and maximum profit. In 1612, Churche declared that ‘improvement of unprofitable lands, as wastes and commons are’ was a ‘safe enriching of the crown and a welcome act to the people’, uniting royal profit and public good.Footnote 113 An analogous correlation was posited between uncultivated, unprofitable commons and the unruly, idle poor who subsisted upon them. In 1637, attorney-general Sir John Banks drew Charles I's attention to an axiomatic reciprocal relationship between poor and commons; ‘your Majesty taking it for a maxime, that idle men and wast[e] lands were the canker of all states’.Footnote 114 Languages of colonization and plantation, invoked to justify ventures in the New World and Ireland, resurfaced in descriptions of the civilizing benefits of English enclosure. Norden thus asserted that commoners were ‘as ignorant of God…as the very savages amongst the infidels’.Footnote 115 Through enclosure, ‘the former unprofitable inhabitants’ would ‘be removed from their obscure dwellings and be replanted where they may first learn and so live according to laws’.Footnote 116 Not only commons, but commoners too were susceptible to improvement and rationalization by enclosure.

Improving visions nevertheless engendered moral opprobrium. Despite claims that surveying was an epistemologically self-sufficient ‘science’ able ‘both to defend and commend it selfe’, surveyors were conspicuously anxious to reconcile their empirical perspectives with legitimating moral concepts of commonwealth.Footnote 117 Norden reconceptualized the powerful image of the body politic to depict surveying as a central organ and conservative lens of surveillance through which a paternalistic agrarian hierarchy could be preserved, writing

is not the eye serveyor for the whole body outward…And is not every mannor a little commonwealth, whereof the tenants are the members, the land the body, the lord the head? And doth it not follow that this head should have an overseer, or surveyor of the state and government of the whole body?Footnote 118

In defending themselves against ‘generall condemnation’, however, surveyors ventriloquized the objections of their detractors, who rejected this vision of social harmony in favour of one of fundamental conflict between landlord and tenant, in which surveyors performed a partisan role.Footnote 119 Norden and Churche brought their ‘surveyor’ into dialogue with an ‘angrie farmer’ who acted as a mouthpiece for ‘common opinion’.Footnote 120 Surveyors were thus denounced as ‘shroade [shrewd] and terrible men’ who were ‘feared and hated of the communalitie’.Footnote 121 More specifically, surveyors were suspected of favouring their patrons’ profits at tenants’ expense by deploying empirical measurements to revoke common rights and raise rents. Norden's ‘farmer’ bitterly lamented that surveyors ‘are the cause that men loose their land: and sometimes they are abridge of such liberties as they have long used in manors: and customs are altered, broken and sometimes perverted or taken away by your meanes’.Footnote 122 Concerns that enclosure would upend the social order were similarly expressed. Threat of popular ‘tumult’ was fresh in the minds of statesmen and surveyors following the large-scale anti-enclosure riots of the Midlands’ Revolt in 1607. Churche's ‘farmer’ thus warned that, through disafforestation, ‘the king should bee greatly scanted in his pleasure, every man wronged, the poore generally be undone, and all would be in an uprore’.Footnote 123

Disafforestation proposals addressed to the exchequer in 1612 by several crown surveyors, including Churche, attempted to neutralize social conflict by marrying empiricism and morality. Disafforestation commissions, they advised, should comprise ‘honest, discreet, and serviceable gentlemen’ and ‘an exquisite surveyor’ and must be ‘able to answer every objection and to meet with every opposition’ to avoid any ‘distrust that may be given to the people’ resulting in ‘clamour’.Footnote 124 If these persuasive procedures were observed, they stated, the crown might ‘happily expect’ disafforestation completed with ‘a generall consent and applaud of every one’.Footnote 125 Over a decade later, arrangements adopted in Gillingham and Braydon, whereby commissioners were instructed to negotiate with forest commoners, closely resembled the proposals submitted in 1612.Footnote 126 Accordingly, at the public meeting held in Gillingham in 1624, Fanshawe delivered ‘a long speech’, evidently anticipating popular concern by offering reassurances that ‘he came not to doe any man wrong or like a moth to eate upp any mans estate’.Footnote 127 Instead, Fanshawe insisted, disafforestation would be a conservative and consensual process ‘p[er]formed to the good content of all men’, whereby each would hold his lands ‘quietly and peaceably…as formerly they had donne’.Footnote 128

The primary mechanism of ‘good content’ was the translation of a paternalistic version of the customary social order into fixed relations of private property. Churche and his fellow surveyors maintained that disafforestation might be undertaken with ‘good conscience’ by ‘allotting everie one his due’. Both commoners and crown were thereby transformed into exclusive landholders so that ‘as well the rich as the poore might reape a generall good’, albeit in vastly differing proportions.Footnote 129 An idealized social hierarchy was to be preserved in the form of newly exclusive property, giving concrete expression to surveyors’ recurring refrain that, through accurate measurement, ‘every man might know his owne’; property and place alike.Footnote 130 In royal forests, Churche's vision of mutual ‘applause’ was transmuted into a contractual obligation as propertied commoners were granted compensatory allotments of land, in proportion to their tenements, in return for their consent to the crown's enclosure of the vast majority of the forest.Footnote 131 Meanwhile, it was emphasized that the poor would be provided for by paternalistic royal benevolence. Concerned that ‘the poorer sort…might not be left destitute’, the crown undertook to grant charitable lands to neighbouring parishes on disafforestation.Footnote 132 Whereas propertied commoners would industriously cultivate individual allotments for personal profit, the poor thereby surrendered independent access to forest resources and were rendered dependent on their social superiors who distributed the charitable lands’ profits.Footnote 133 As mandated by successive poor law legislation, which centrally directed localized poor relief, the ‘better sorte’ thereby became ‘governors of the poore’, differentiating the deserving from undeserving in an attempt to inculcate disciplined labour habits.Footnote 134 According to Norden, just as surveyors should observe and reform unprofitable lands, so local officers, as ‘surveyors of the commonwealth’, should also ‘see into, informe, punish, and reforme’ the unruly poor.Footnote 135 The propertied thereby became agents of improvement and the poor its subjects.

Alongside careful social mediation, the landscape was recast via empirical principles. New measuring techniques cut land loose from customary relations by translating it into standardized units, comparable and transferable on a national land market. Although the standardized statutory acre had been legislatively enshrined in the thirteenth century, a multiplicity of local use-based denominators persisted in practice into the seventeenth. While Rathborne acknowledged that ‘most tenants will seeme ignorant’ of their land's acreage, Norden's ‘farmer’ argued that adherence to customary measures reflected preference, not ignorance, since land might be better valued ‘by knowing what cattle a ferme or demaines will keepe’ or ‘how many load of hay such a meadow will yeeld upon every acre’ than ‘all your nice tricks of measuring’.Footnote 136 Customary denominations were rooted in the rhythms of small-scale agriculture, denoting intimate familiarity and subjective appraisals of use, yield, or labour rather than empirical extent. Prior surveys of royal forests, meanwhile, were aimed at intensifying customary exploitation and thus relied on basic calculations of rents and tenancies. An exchequer survey of Gillingham Forest and Manor conducted in 1616, for example, simply summarized total rent paid by freeholders and customary tenants respectively.Footnote 137 By contrast, disafforestation commissioners in Braydon were ordered to determine ‘the quantitie and qualitie’ of all lands to be enclosed, alongside ‘the true yearely value that [they]…will then yield to bee lett’.Footnote 138 Jenkin's survey of Gillingham Forest, drawn up in 1624 as a preparative to disafforestation, returned detailed measurements of square acres and value per acre, as well as the number and value of oak trees.Footnote 139 New synoptic forms of standardized measurement thereby converted land previously valued according to customary use or tenants into alienable property to be managed as an asset (Figure 4).

Fig. 4. An engraving from Hopton's Speculum topographicum (p. 189) instructing the surveyor in measurement of square feet of timber using the ‘Geodeticall Staffe’. © The British Library Board: 1609/5078.

Turning land to profit required a concomitant enclosure of knowledge from the collective ‘memory of the people’ to surveyors’ specialized oversight. Rathborne and Hopton claimed to supplant the authority of customary perspectives by applying a purely geometric lens. Surveyors’ autonomous epistemology was epitomized by their purported ability to measure a field's surface area from a single vantage point with a complex geometric instrument known as a theodolite (Figure 5).Footnote 140 The landscape was thereby transmuted into subject, rather than source, of knowledge. In practice, however, the relationship between local customary and central empirical epistemologies was more ambiguous. Norden was exceptional amongst surveyor-authors in qualifying geometric ideals: he not only critiqued tenants’ mutable testimony, but also rejected surveying techniques that solely relied on time-consuming and ‘unprofitable’ instruments and ‘rules geometricall’.Footnote 141 Such methods, Norden argued, could produce only formal representations of the land that lacked detail of ‘every street, high-way, lane, river, hedge, ditch, close, and field’.Footnote 142 His preferred mechanism of measurement was an adaptation of customary rituals of perambulation, whereby surveyors were assisted in using a basic linear instrument, the ‘chaine’, by ‘the most auncient, and longest inhabitants within the mannor, for the surveyors instruction, and the youngest, to the end that they may also learne to know the like, to give like ayde by their experience to posterities’.Footnote 143 In Gillingham and Braydon, epistemological techniques deployed during disafforestation were far closer to Norden's prescriptions than to Hopton's and Rathborne's empirical ideals. Commissioners in Braydon were instructed to collate information through oral, measured, and written forms of evidence: ‘the oaths of good and lawfull men’, as well as ‘records, surveys [and] p[er]ambulac[i]ons’.Footnote 144 Deponents, meanwhile, were asked to recount the quantity of land and wood ‘reputed, accompted, or taken’ to be in Braydon, including ‘the p[ar]ticular numbers, quantities, names, and extents’.Footnote 145 Nevertheless, even as the interrogatory acknowledged the ‘reputed’, uncertain nature of collective perceptions, deponents were obliged to convert their experiential knowledge into categorized and quantified measures, making the landscape available to the oversight of unfamiliar landlords.

Fig. 5. A page from Hopton's Speculum topographicum (p. 34) instructing surveyors in measurement of a field from a single vantage-point. As Norden highlighted, however, this technique involved the complex computation of different angles and distances, leading the surveyor to ‘toyle himselfe and his companions, more then if he went the true course of arte and reason’ (Dialogue, p. 118). © The British Library Board: 1609/5078.

Transmission between customary epistemologies and written and measured equivalents was not unilinear. Empirical survey could also be appropriated into personal memory, as demonstrated when yeoman John Bath validated his account of the extent of Keynes Wood in Braydon Forest by recalling his attendance at ‘the measureing of the sayd ragg’ as a child sixty years earlier.Footnote 146 Similarly, Gillingham tenants retained in their church chest an earlier exchequer ‘confirmation’ of customs, for which they had collectively paid around £900 in James I's reign.Footnote 147 The document was of ‘fimous memorie’, evidently assuming talismanic significance within the tenants’ collective memory as a recent written safeguard of immemorial rights.Footnote 148 In general, however, the literate legal authority of disafforestation proceedings proved inaccessible to illiterate commoners. A former bailiff of Gillingham Manor, John Gatehouse, reported seeing ‘a writinge w[i]th a great seale of yellow wax’ in March 1624, which he was told was the commission; its materiality rather than content conferring authority.Footnote 149 He attended the commission's hearings at Gillingham, but reported that ‘he knoweth not what was then and ther[e] done concerninge the said forrest by reason the com[mission]ers withdrew themselves unto a private roome whereuppon this deponent departed’.Footnote 150 If customary knowledge was a source of collective power over forest resources, often illegible to elites, then commissioners’ and surveyors’ legal and empirical knowledge likewise conferred power over those who lacked the means to decode it.

Nowhere was the active epistemic force of surveyors’ empiricism more evident than in processes of mapping (Figure 6). A sixteenth-century growth in cartographic consciousness had seen new mapping techniques deployed during plantation in Ireland, while popular county atlases produced by Christopher Saxton and John Speed have been dubbed part of an Elizabethan ‘re-discovery of England’.Footnote 151 As a renowned cartographer in his own right, Norden described an estate map as a ‘lively image’ whereby ‘the Lord sitting in his chayre may see what he hath, where and how it lyeth, and in whose use and occupation every particular is, upon the suddaine view’.Footnote 152 The relationship posited between viewer and landscape, as depicted in maps, was one of dominion in which knowledge was power over landscape and inhabitants. Without such oversight, Norden alleged, customary epistemology vested tenants with the capacity to manipulate memory and thus the landscape: ‘to alter names and properties, to remove meeres, and to cast down ditches, to stocke up hedges, and to smoother up truth and falshood under such a cloake of conveniencie, as before it be suspected or found out by view, it will be clene forgotten’.Footnote 153 Hence, Norden promoted maps’ fixity as a corrective, wresting epistemological authority from customary memory and granting landlords control over a terrain exclusively available to their view so that ‘no such trechery can be done against the Lord’ (Figure 7).Footnote 154

Fig. 6. This image from Hopton's Speculum topographicum (p. 146) illustrates how to draw a ‘seacard’ to ‘beautifie your map’. Whilst purely ornamental, it depicts the overlaying of surveyors’ geometric and rationalized perspective onto a landscape shaped by use, as demonstrated by the meandering footpaths. © The British Library Board: 1609/5078.

Fig. 7. The ornate ‘scala perticarvm’ (scale of perches) on Jenkins's 1624 map of Gillingham Forest. Dorset History Centre, D.1366/1.

Disafforestation maps, however, were intended actively to transform spatial relations, rather than to fix or reflect. In Braydon, a scale map produced in 1630 projected a vision of the enclosed forest, redrawing it in line with exchequer instructions to divide the crown's disafforested lands for ‘husbanding and improvement’ (Figure 8).Footnote 155 The map was a partial representation, indicating only areas in which the crown asserted exclusive possession and dividing these into four portions of equal value, each measured precisely in acres, roods, and perches, to be allocated to crown lessees, Dutch jeweller, Philip Jacobson, and London merchant, Edward Sewston.Footnote 156 Roughly a third of the forest lying to the east was omitted, marked merely by notes indicating charitable lands allotted to the poor and thus literally relegating poor commoners to a marginal position.Footnote 157 Despite detailed depiction of local landmarks, the poor's unsanctioned cottages were not featured, effectively rendering them invisible and expendable. Such maps became definitive and authoritative records, which were successfully deployed in legal disputes during disafforestation.Footnote 158 One such dispute emerged in Braydon in May 1630 between the crown and the lords of Little Chelworth Manor concerning ownership of 430 acres within the forest variously known as ‘Peverells’, ‘Exchequer’, or ‘Kings’ woods.Footnote 159 Place names within forests often reflected historical ownership, and areas once granted to forest custodians continued to bear their names. In the resultant exchequer case, locals testified that they were ‘all one and the same woods’, ‘knowne by all the said sev[e]rall names’, reflecting fluidity of nomenclature and ownership.Footnote 160 As place name became a critical means of staking ownership, however, Thomas Sadler invoked ‘Peverell’ as evidence that the wood ‘did aunciently belonge’ to Little Chelworth Manor, ‘se[e]ing the woods and mannor were bothe in the possession of Hughe Pevrell att one tyme’, while others alleged that it was an innovation ‘of late crept in’.Footnote 161 The enclosure map, finalized in the year of the dispute, unequivocally asserted the exchequer's possession by denoting the woods simply as ‘Chequer woods’.Footnote 162

Fig. 8. A scale map of Braydon Forest, drawn up in 1630 to divide the disafforested land between the crown's lessees. This map is taken from a reproduction by Canon F. H. Manley of the original held in The National Archives (TNA MPC1/51). Reproduced here with the kind permission of the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society.

IV

Disafforestation maps did not restructure landscapes by intention alone, however, and lines first drawn by surveyors were not so easily inscribed within forests. Rather, paper boundaries were forced to contend with non-cartographic methods of constructing space embedded in the forest commons.Footnote 163 Although consent to disafforestation had been gained in principle, direct conflict emerged between customary and empirical ways of seeing and using the forests at their physical division. Conflict took two forms: the first, in Gillingham, was a litigious challenge to Jenkins's division of the forest, while the second, emerging first in Gillingham and later Braydon, was a spatial contestation via large-scale riots.

Jenkins's attempt to allocate compensatory allotments in Gillingham precipitated a chorus of concerns, ranging from individual complaints to larger collective demands, and resulted in an exchequer case in March 1627 and a further exchequer commission that August ensuring ‘remedye maie be given’.Footnote 164 It is significant that Jenkins and his surveying methods emerged as the primary focus of aggrieved tenants’ anger. Jenkins had been central to Lord Treasurer Cranfield's early attempts at disafforestation in 1622 and also acted as Fanshawe's agent during parallel Fenland drainage.Footnote 165 Despite his evident experience, however, Jenkins disregarded the crown's recommended circumspection. Although Fanshawe and Fullerton had specifically instructed Jenkins and the exchequer commissioners to ‘call a certaine number of the freeholders and ten[a]nts to assist them in settinge out the allotm[e]nts’, several witnesses testified that Jenkins had acted alone, with neither commissioners’ sanction nor tenants’ consent.Footnote 166 The bailiff of Gillingham Manor, John Woolridge, recalled that there were ‘noe comissioners there…but onely one Mr Jenkins’ who ‘was surveyor onelie’, driving a wedge between the commissioners’ legitimate representation of royal authority and Jenkins's status as a mere technician.Footnote 167 Thomas Banister further testified that none of the tenants present ‘could doe anie thing therein they being wholie overruled by Mr Jenkings who did what he himself pleased to doe’.Footnote 168 Accusations of Jenkins's autocratic imposition of new boundaries resonated with popular depictions of tyrannical surveyors riding roughshod over tenants’ rights.

Further, despite surveyors’ manifest concern to proclaim their skill and honesty, complaints of inaccuracy and unfairness plagued Jenkins. Many claimed that allotments had not been performed according to the original agreement since some had been allotted less than promised, while sixty were left with ‘noe manner of allowance att all’.Footnote 169 Richard Snook, who had his newly enclosed grounds measured independently, found himself short by 1 acre and 71 perches.Footnote 170 Even Jenkins's employee, a London gentleman called John Hinde who had physically measured out the allotments, admitted that he ‘cannot pr[e]cisselie swe[a]re that all the ten[a]nts…have their juste allotments’.Footnote 171 Whether Jenkins was dishonest or incompetent was a moot point: the relationship between precision and justice, implied in Hinde's statement, was inverted by the Gillingham tenantry, who deployed allegations of inaccuracy to claim injustice.

The practical result of Jenkins's disregard for local knowledge was an entirely unworkable schematic grid of enclosed allotments. Many allotments were ‘made of the high waies and lanes’, obliterating rights of way and obstructing access to the forest's remaining common resources, including watering places, quarries, sand pits, and reed beds.Footnote 172 Consequently, it was reported that ‘manie of the ten[a]nts are soe shutt up even to their doores’.Footnote 173 Local yeomen emphasized the socially segregating impact of forest's spatial division, asserting that, in attempting to traverse the enclosed forest, ‘the poore inhabitants…shall become trespassers unto their neighboures unto whome the said grounds soe to be inclosed are allowed’, leading to ‘verie manie [legal] suits’.Footnote 174

In contrast to their litigious propertied neighbours, the landless poor rose in unequivocal dissent as the crown's lessees began to erect fences. During the winter of 1626–7 and early 1628 in Gillingham and in May and June 1631 in Braydon, hundreds of commoners gathered in ‘a great and well-armed number’ to resist enclosure.Footnote 175 These ‘tumultuous assemblies and outrages’ quickly came to the privy council's attention and were condemned as undermining both royal fiscal interests and social order, for ‘such like rude accions [were] not to be tolerated in a well governed state’.Footnote 176 Analogous riots in other western forests fuelled anxieties about a co-ordinated spread of unrest, rendering them ‘in the nature of rebellions rather than riotts’.Footnote 177 Consequently, historians such as Eric Kerridge and David Allan have been tempted to impose retrospective unity on Caroline disafforestation riots under the collective banner of the ‘Western Rising’.Footnote 178 Yet, as Sharp has demonstrated, there is little evidence to substantiate either central fears or subsequent historiographical framings of centrally orchestrated rebellion.Footnote 179 Nevertheless, news of the riots spread across the region and certain individuals may have even moved between different forests. One soldier, William Gough, recalled drinking in Bristol and ‘talkinge of the Forest of Deane’ with his comrades, ‘and of the stires in the Forest of Braden’.Footnote 180 The Gillingham and Braydon riots were, however, predominantly local uprisings of the landless poor. In letters ordering local officers to apprehend offenders, the privy council distinguished between ‘ringleaders’ and ‘others as be of the poorer sort’, echoing the prevalent belief expressed by the Jacobean statesman, Sir Francis Bacon, that ‘common people are of slow motion, if they be not excited by the greater sort’.Footnote 181 However, the alleged ringleaders of the Gillingham and Braydon riots, eventually identified in the Star Chamber, were almost uniformly drawn from the ranks of ‘common people’: a tailor, carpenter, baker, and yeoman in Gillingham, and a tailor, sieve-maker, and gardener in Braydon.Footnote 182 Largely landless and reliant on the forest's raw materials and grazing, these leaders were representative of the mass of rioters. The occupational statuses of rioters eventually convicted in the Star Chamber confirmed that they were predominantly clothworkers, husbandmen, and various ‘artificers’ with little land.Footnote 183

Even as the privy council repeatedly called on local officials to reimpose order, it remained fundamentally uncertain of its command. As Wrightson has demonstrated, the maintenance of early modern provincial order relied on local, unpaid officials who mediated between central statutory and localized popular notions of order and justice.Footnote 184 The breadth and depth of local support enjoyed by the rioters reflected the competing authority of customary concepts of right, akin to the ‘legitimizing notion(s)’ underpinning ‘the moral economy of the poor’ that Thompson detected in eighteenth-century food riots.Footnote 185 Rioters were estimated to number hundreds in Gillingham and up to a thousand in Braydon.Footnote 186 A crown agent in Braydon, Simon Keble, reported that ‘[t]he countrey is in a miserable combust[i]on, and have w[i]th a generall consent combined themselves together’ and further alleged, perhaps exaggerating, that ‘there is not 6 men free of the cominac[i]on of 18 towneshipps’ who had not ‘given money or victuals for the mayntenence of these insufferable rebels’.Footnote 187 Meanwhile, Gillingham rioters were said to have ‘bound themselves by oaths to be true one to the other’, pledging to act as a united group.Footnote 188 News and solidarity also spread beyond the forests’ immediate vicinity. Requested to lend assistance in suppressing the riots, Henry Barrett, an innkeeper in the town of Devizes twenty miles north of Braydon, ‘in a contemptuous manner refused to goe’ with ‘jeering and unbeseeming speeches’, reportedly inciting others by ‘his ill example’.Footnote 189 In Gillingham, a locally stationed regiment of soldiers likewise refused to aid local officers and instead became active ‘hinderers’ who rescued rioters taken prisoner.Footnote 190

Rights founded in practice were defended in practice by commoners’ riotous contestation of exclusive boundaries. Their spatial disordering and un-mapping undermined attempts to rationalize the forests and rendered them again illegible from the centre. No sooner had Fullerton's workmen ‘inclosed, railed and fenced’ off enclosures than they were undone again by the ‘unfencers of Gillingham forest’.Footnote 191 Despite the riots’ perceived incoherence, a systematic logic can be discerned. Gillingham rioters were reported to ‘throw down, and fill up the ditches and fences there about three miles in length’, methodically sawing up and burying the rails and posts.Footnote 192 The role of physical boundaries in spatially and symbolically manifesting private property was reflected in complaints that Braydon commoners had destroyed enclosing hedges so that ‘the farmers should never be able to improve or inclose’ and ‘all things is nowe in comon’.Footnote 193 Rioters also collectively expropriated forest resources, killing deer and cutting down trees in Gillingham, and thereby openly claiming venison and vert which had hitherto been covertly poached and pilfered.Footnote 194 Meanwhile, the single reported speech act of Gillingham rioters – ‘here were we born, and here we will die!’ – conveyed a powerful articulation of a birthright by which commoners were inextricably knitted to their commons.Footnote 195 Social unrest acquired performative dimensions in Braydon when rioters donned ‘disguised habits’ and ‘women's clothes’ to invoke Lady Skimmington, a folkloric figure embodying communal dissent.Footnote 196 A skimmington had long been a ritualized expression of collective disapproval in Wiltshire. Taking the form of a noisy and raucous community procession, it invoked the symbolism of inversion to shame those who transgressed popular morality.Footnote 197 During disafforestation, Braydon commoners transmuted this ritual to embody the moral and social inversion engendered by enclosure in gendered terms.

Rioting commoners were adept at resisting arrest and obscuring their identities from the central authorities; they often acted at night, wore disguises, and relied on their familiarity with the forest to evade officials attempting to execute Star Chamber orders.Footnote 198 When local agents succeeded in apprehending rioters, others materialized to beat them and release the prisoners.Footnote 199 In Braydon, the sheriff and his assistants were shot at when they arrived to suppress the riots, while Gillingham commoners burnt ‘forty of the Lord's letters, and forty processes out of the Star Chamber, and whipp[ed] the messengers at a post’.Footnote 200 Unsurprisingly, local officers became reluctant to act for fear of reprisals. As Keble reported, some justices of the peace ‘are unwillinge to be seene actors in any thing against their neighbors’.Footnote 201 Keble himself, who lived in Braydon Forest and was responsible for providing ‘records and evidences’ to the commissioners, was subject to violent community retribution, while his workmen were warned not to ‘give any intelligence’ revealing rioters’ identities on pain of similar penalties.Footnote 202 Consequently, Keble complained that he ‘cannot gett any man to depose anythinge before the Justice here or to come to London to make affadavit’.Footnote 203 These tactics effectively obstructed mechanisms of central authority, including written commands, coercive force, and evidence gathering. Less than a quarter of rioters identified by the Star Chamber were ultimately apprehended and fined.Footnote 204

Eventual enforcement of new boundaries relied on the crown's analogous assertion of symbolic and physical force. Purported ringleaders were singled out for both heavy fines and public humiliation.Footnote 205 In Braydon, ringleaders were placed in the pillory at assizes ‘in womens clothes as they were disguised in the riots, with papers on their heads declaring their offences’, before being ‘well whipped’.Footnote 206 Fines were used to coerce continued quiescence. In Gillingham, where the crown's lessee, Fullerton, assumed direct control of the fines, he ‘keep[t] the rodd in his owne hands’ by wielding them as a threat to ensure commoners ‘would prove honest men and trouble him no more’ in the ‘forrest buisnes’.Footnote 207 Only an uneasy truce resulted, however, as demonstrated by renewed forest riots amid the national breakdown of central authority in the 1640s. Between 1642 and 1648, Gillingham tenants, ‘taking advantage of the times’, destroyed enclosing forest fences and refused rent to Fullerton's heir, the earl of Elgin, while Braydon enclosures were destroyed by ‘the poore of the neighboring parishes’ in the late 1640s.Footnote 208 Legal disputes over charitable lands allocated to poor commoners extended well into the eighteenth century, hinging on whether such lands constituted specific compensation for loss of forest rights or could be administered by rate-paying parishioners to lessen the general burden of poor relief.Footnote 209 In these ways, communal memories of collective forest rights endured and were mobilized for almost a century following disafforestation.

As the first significant incursion of the English crown into ‘improvement’ and enclosure, disafforestation crossed a threshold, breaking with the Tudor moral consensus regarding its deleterious effects on the social body. In print, surveyors promised to alchemize land by rendering it legible in synoptic units and cartographic perspectives, heralding the transformative and profitable potential of information gathering. Paul Slack's triumphal assertion that ‘English improvement worked’ obscures, however, the profound conflicts – epistemological and spatial – that marked the making of private property within early modern landscapes.Footnote 210 Printed discourses and improving intentions can tell only half the story: the rest lies in incomplete archival remnants and the muddy terrain of the landscape itself. In practice, the crown faced immense difficulties in inscribing improving ideals on ‘waste’ landscapes alive with unruly commoners. Even as surveyors and statesmen attempted to render land separable and alienable from its inhabitants, they were forced into dialogue with older legitimating notions of custom and commonwealth. During disafforestation, this tension manifested itself in attempts to transmute a paternalistic version of the customary social hierarchy into new relations of exclusive property. Practices of agrarian improvement nevertheless involved a radical reconfiguration of spatialized social relations and engendered fundamental epistemological conflicts. Forests measured, mapped, and divided by surveyors in pursuit of their patrons’ profits were simultaneously sites of customary praxis that legitimated commoners’ assertive claims. These unwritten and mutable customs not only knitted commoners to ‘their’ common and presented an illegible impediment to royal profit and authority, but were also mobilized in riotous defence of forest rights. Faced with concerted resistance, the crown abandoned disafforestation from 1632 onward, preferring to resurrect feudal forest laws in an attempt to raise revenue through archaic fines levied on forest offenders.Footnote 211 It is insufficient, therefore, to cast the literate protagonists of ‘progressive’ improvement against an ill-defined background of regressive, historically voiceless ‘losers’. Rather, only in examining ‘improvement’ as spatialized practice can relations be illuminated between different ways of seeing and using land that underwrote its contested inscription within the early modern English landscape.