Introduction

In a recent Antiquity paper entitled ‘Kossinna’s Smile’, Volker Heyd (Reference Heyd2017) uses the results of genetic analyses of individuals from the Central European Corded Ware Culture to establish a direct link between the emergence of this group and the Yamnaya Culture of the Eurasian Steppe to the east. Such a connection also supports the classic hypothesis relating to the westward spread of Proto-Indo-European languages from the steppe during the Chalcolithic period (Gimbutas Reference Gimbutas1997; Mallory Reference Mallory1997; Lebedynsky Reference Lebedynsky2014). Heyd posits that the Yamnaya impact on third-millennium BC Chalcolithic cultures is not only restricted to genetic transmission to the Central European Corded Ware, but is also seen in the spread of anthropomorphic stelae and statue-menhirs, cultural influences reaching as far as southern Iberia, and in a possible connection with the Bell Beaker phenomenon in Western Europe. Heyd therefore also proposes that the third millennium BC was a time of large-scale, long-distance cultural interactions. In the present paper, partly as a response to that published by Heyd, I wish to comment on three issues among the many raised therein: the anthropomorphic stelae, the Chalcolithic funerary rituals and grave goods of southern Iberia, and the origins of the ‘Maritime’ Bell Beaker tradition.

The issue of anthropomorphic stelae

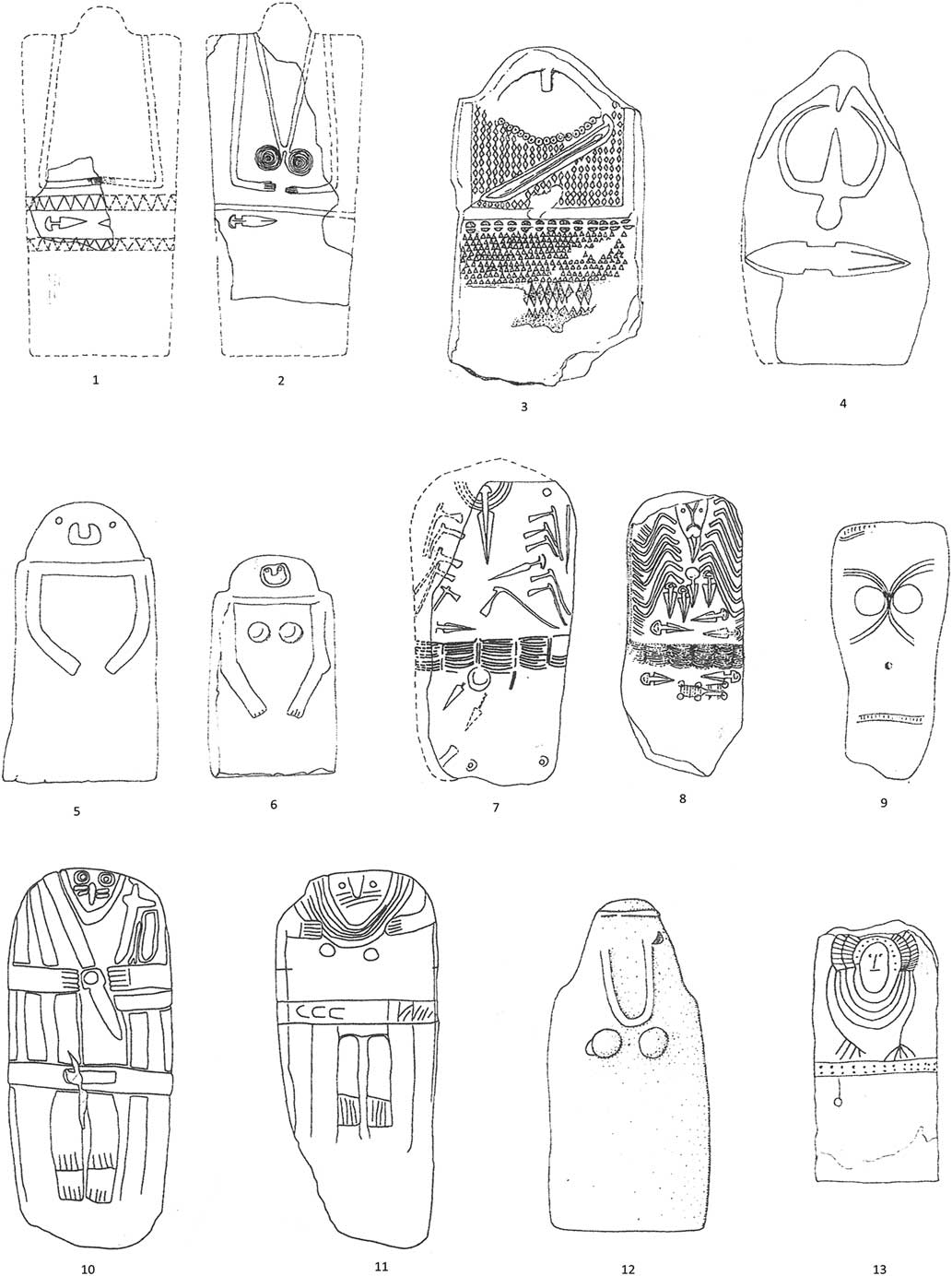

The view that the concept of anthropomorphic stelae spread from east to west is not new, whether the origin is thought to be the Trojan area or the Pontic region (Childe Reference Childe1925; Arnal Reference Arnal1976). The Pontic hypothesis is often associated with the dissemination of eastern-style objects as far west as the Italian Peninsula: the ‘battle axes’ of the Rinaldone Culture and the hammer-headed pins of both the Remedello Culture and the Gaudo group (Guilaine Reference Guilaine1994). It cannot, however, be denied that the various western groups of anthropomorphic stelae (e.g. Trento-Adige, Lunigiana, Sion-Aosta, Sardinia, Languedoc, Rouergue and Iberia) vary considerably from one another in both typology and characteristics (Casini et al. Reference Casini, De Marinis and Pedrotti1995; Mezzena Reference Mezzena1998; Rodriguez & Marchesi Reference Rodriguez and Marchesi2015) (Figure 1). There were obviously several contributing ‘groups of artists’ or ‘schools’ (Guilaine Reference Guilaine2017), although their emergence is neither precisely dated, nor necessarily synchronous with the Yamnaya-Corded Ware-Bell Beaker horizon.

Figure 1 Variability of statues-menhirs and anthropomorphic stelae of Western Europe: 1–2) Petit-Chasseur (Sion, Switzerland), early stage; 3) Petit-Chasseur (Sion, Switzerland), recent stage; 4) Monte Ferreddu Barrili (Sardinia); 5) Pontevecchio (Lunigiana, Italy); 6) Moncigoli (Lunigiana, Italy); 7–8) Lagundo F and B (Upper Adige, Italy); 9) Castelluccio dei Sauri (Sterparo, Daunia, Italy); 10) La Jasse (Miolles, Tarn, France); 11) Frescaty (Lacaune, Tarn, France); 12) Catel (Guernsey, Channel Islands); 13) Catel (Guernsey, Channel Islands) (after Ambrosi Reference Ambrosi1972; Almagro Gorbea Reference Almagro Gorbea1993; Gallay Reference Gallay1995; Kinnes Reference Kinnes1995; Tunzi Sisto Reference Tunzi Sisto1995; Atzeni Reference Atzeni1998; Maillé Reference Maillé2010).

For example, the Rouergue group—one of the largest and the most innovative—should be assigned to the Late Neolithic of southern France (c. 3500–3000 BC). The ‘shafted axes’ depicted on male statues could represent maces or antler hammers known from the archaeological record (Jallot & Sénépart Reference Jallot and Sénépart2008). The ‘Y-shaped pendants’ of the female statues are reminiscent of ‘grooved pendants’ also made of antler and dated to the same period. Interpretation of the depictions of the so-called ‘object’ placed diagonally across the chest of male statues, however, is more difficult. It is often considered to be a dagger (Serres Reference Serres1997; Maillé Reference Maillé2010; Maillé & Vaquer Reference Maillé and Vaquer2011), but it would be made of flint, as daggers with copper blades are rare before 3000 BC.

I agree with Heyd that the dagger is the most frequently depicted element on these stelae. Daggers with flint blades, however, appear in Western Europe during the mid fourth millennium BC (from the outset they may rival distinct copper blades of the Rinaldone Culture). By analogy with the archaeological record, the Remedello-style daggers depicted on the stelae (e.g. Trento-Adige, Sion-Aosta, Lunigiana) can be dated to between 2900 and 2500 BC (phase II of the Remedello Culture; De Marinis Reference De Marinis1994, Reference De Marinis2013); the ‘object’ depicted on the statue-menhirs in southern France, thought to represent a flint dagger, to a few centuries earlier. Thus, the hypothesis of an east to west spread of the ‘stelae phenomenon’ and a link with the Yamnaya Culture is invalidated.

A similar line of argument arises from the Armorican stelae (e.g. Trévoux-Laniscar, Le Catel Guernesey, Kermené-Guidel) with their necklace and breast ornamentation paralleled by carvings on distinct supporting pillars of megalithic gallery graves in Brittany (e.g. Prajou-Menhir, Mougau-Bihan, Tressé) and the Paris Basin (e.g. Bellée, Le Bois-Couturier, La Pierre Turquaise, Aveny). The latter can be dated to c. 3300 BC or even earlier (Kinnes Reference Kinnes1995; Cottiaux & Salanova Reference Cottiaux and Salanova2014).

The Pontic stelae developed in two distinct stages. The early stage is characterised by stelae exhibiting a schematic protruding head or apical rostrum: these are rarely decorated—at most featuring a belt. The later stage is characterised by carved stelae with attributes (e.g. anatomical characteristics, weapons, ornaments) (Telegin & Mallory Reference Telegin and Mallory1995). A similar, albeit three-staged, process occurred across Western Europe. During the fifth millennium BC, the emergence of stelae and standing stones exhibiting a schematic protruding head or apical rostrum are noted within various cultural contexts (e.g. Armorican passage graves, the stone alignment of Yverdon, Switzerland, and the anthropomorphic standing stones on Sardinia). During a second stage, groups of stelae that place particular emphasis on the face appear (e.g. the Maltese stela of Zebbug, and the Trets group of stelae from Provence, which dates to c. 3800 BC). A third stage is characterised by the ‘genuine’ statue-menhirs exhibiting ‘objects’ in the Rouergue and Languedoc regions, or a Remedello-type dagger in northern Italy. Various phases, however, existed within the third stage, including the monuments of southern France assigned to the Saint-Ponian and Ferrières horizons. These probably pre-date stelae of the Italian groups (Guilaine Reference Guilaine2017).

The significance of this brief overview is ambiguous. On the one hand, it demonstrates common attributes, such as the belt or dagger, among several Southern European stelae groups. Yet the dates of these features are apparently inconsistent with the idea of a single East European origin, from which regional variants would have stemmed. The internal chronology of these various groups remains a topical issue.

The southern Iberian Chalcolithic funerary evidence

According to Heyd, another Western reflection of burial rites from the steppe can be identified in southern Iberia, in the form of distinct funerary practices. Examples include the ochre stains near the individual buried in chamber 10049 in the PP4-Montelirio sector (or the red pigments made from cinnabar sprayed over the individuals of the Montelirio tholos—a particular megalithic monument unique to the area), and the presence of sandals made of ivory, stone and even gold, from burials in this region (e.g. Los Millares, Almizaraque, Alapraia, Seville) (Heyd Reference Heyd2017). These two examples merit further discussion. The covering of deceased individuals with red mineral powder is an ancient ritual in Western Europe and was practised from at least the Upper Palaeolithic to the Neolithic (Duday Reference Duday1975; Grifoni & Radmilli Reference Grifoni Cremonesi and Radmilli2001). An autochthonous tradition, rather than an influence from the steppe, therefore, cannot be ruled out. At the same time, recent archaeological discoveries from the South-eastern Mediterranean (e.g. the southern Levant and Egypt) may suggest exogenous influences on southern Iberia from places other than the steppe. These can be summarised as follows:

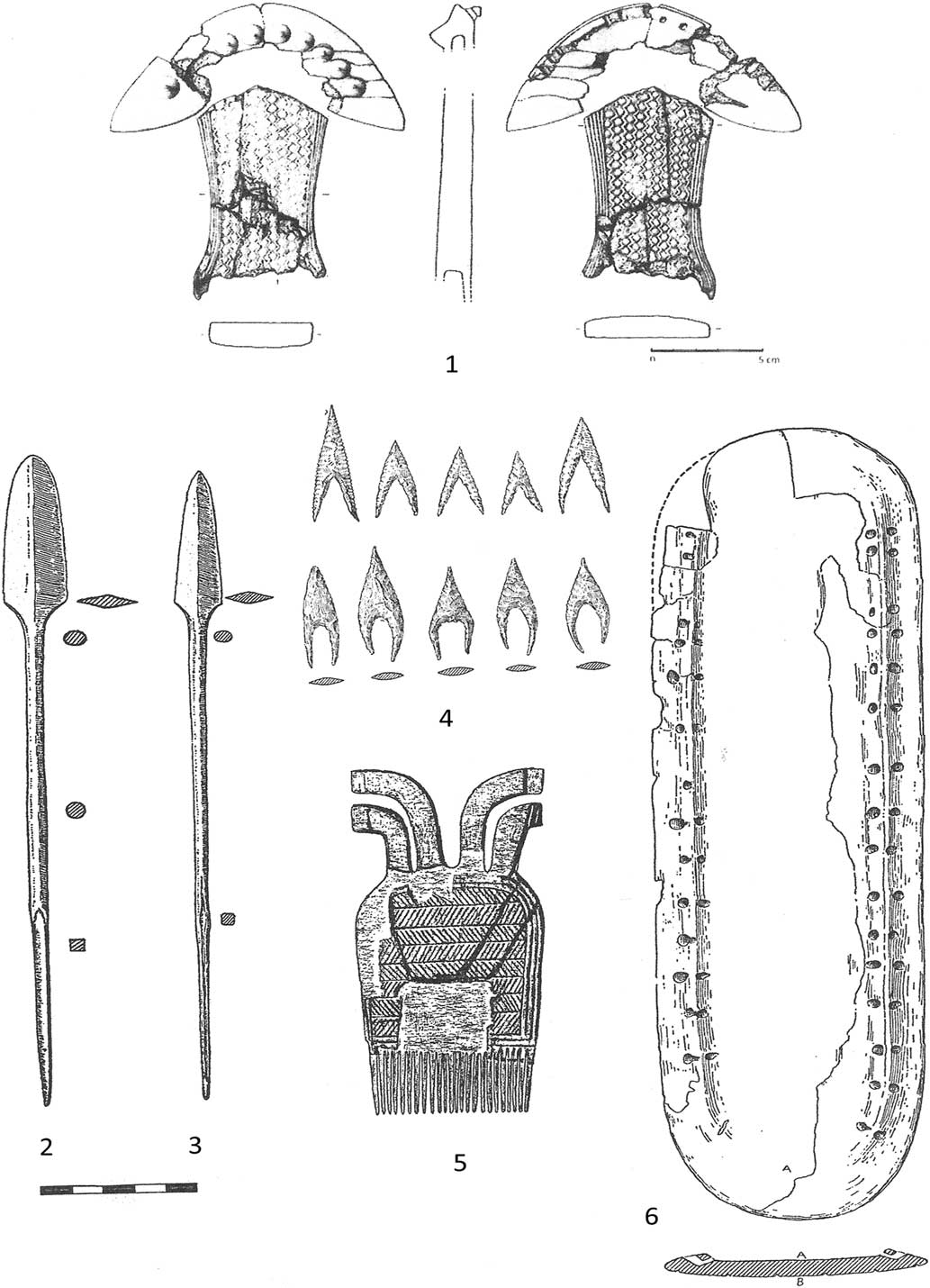

1) The term ‘sandals’ describes sole-shaped ivory, stone or gold objects that have been discovered in several southern Iberian sites (e.g. Almizaraque, Los Millares, Alapraia). It is, however, uncertain whether these objects were actual sandal soles, particularly as one gold example from the Montelirio tholos depicts ‘solar eye’ patterns. These can be linked to Iberian figurines exhibiting a similar iconography (Murillo Barroso Reference Murillo Barroso2016a). Yet Heyd maintains the ‘sandal’ hypothesis, drawing comparisons with the sandal sole patterns depicted on Ukrainian stelae. These sandals could, however reflect Egyptian, rather than Ukrainian influences (Figure 2.6). In the Nile area, sandals were an important indicator of social status (Cherpion Reference Cherpion1999) as early as the Neolithic and Predynastic periods. Grave U160 of the Hu cemetery at Diospolis Parva, for example, has yielded imitations of ivory sandals painted in red, while grave 24 at Adaïma contained sandals on a stucco base painted in red or white (Cherpion Reference Cherpion1999, citing Petrie; Crubézy et al. Reference Crubézy, Janin and Midant-Reynes2002). Furthermore, the Narmer Palette, dated to c. 3000 BC, depicts the social role of the pharaoh’s ‘sandal-bearer’. Towards the end of the third millennium BC, Nubia provided Egyptian society with leather and skins for the manufacture of clothing and sandals (Moreno García Reference Moreno García2018). In Egypt, the use of ivory testified to the wealth of the deceased (Cherpion Reference Cherpion1999). The ‘sandals’ discovered in southern Iberian tombs may therefore indicate the wide Mediterranean contacts of the regional elites. Although this argument would fail to convince on its own, it is supported by further evidence.

2) The ‘horned’ ivory comb of grave 12 from Los Millares (Leisner & Leisner Reference Leisner and Leisner1943) and the combs with carved animal heads from the Montelirio tholos also have prototypes from Predynastic (and later) Egypt (Figure 2.5).

3) The ritual deposition of elephant or hippo tusks is observed from the Egyptian Naqadian period (c. 3200–3000 BC) onwards. These items are also found at the Andalusian elite tombs (e.g. the Montelirio tholos and the megalithic monument 10042-10049).

4) The impressive ‘Alcalar’ arrowheads, with their narrow and exaggerated tails are restricted in their distribution to tholoi in the very south of Iberia (Figure 2.4). The arrowheads of the dolmen of Ontiveros and those discovered in the Montelirio tholos, made of rock crystal or melonite, are the most remarkable (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Lozano Rodriguez, Sanchez Liranzo, Gibaja Bao and Aranda Sánchez2016). Prototypes for these arrowheads are attested in Egyptian Predynastic graves (Tristant Reference Tristant2004; Friedman Reference Friedman2008).

5) Stylistic parallels exist between the figurines from the Levantine Ghassulian, the Naqadian and a small assemblage of Iberian ivory or bone objects including a stiff posture with crossed arms. The possible Near Eastern prototypes, however, were modified and rendered in an Iberian style, particularly through the use of chevrons to depict long hair (El Malagon at Cullar-Baza, Marroquies Altos and Torre del Campo at Jaen, Cerro de la Cabeza at Seville; Arribas Reference Arribas1977).

6) The analyses of southern Iberian ivory artefacts suggest the use of Asian elephant ivory (Figure 2.1). A workshop for processing this material has been discovered at Valencina de la Concepción (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Luciañez Triviño, Schuhmacher, Wheatley and Banerjee2013a; Nocete et al. Reference Nocete, Vargas, Schuhmacher, Banerjee and Dindorf2013) (Figure 3). This elephant ivory could not have been transported via the large Mediterranean islands (e.g. Cyprus and Crete), as these have yielded only third- and second-millennium BC objects made from hippo ivory. A land or sea route from the Levant or the Nile Delta along the North African coast should therefore be considered.

7) The assemblage of javelin-heads from the Pastora dolmen clearly match Levantine prototypes, although the former were made from Iberian copper (Hunt Ortiz et al. Reference Hunt Ortiz, Martinez Navarrete, Hurtado Perez and Montero Ruiz2012; Figure 2.2–3).

Figure 2 Markers of status of the Chalcolithic in the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula: 1) dagger hilt made of ivory (megalithic monument 10042-10049, PP4-Montelirio, Valencina de la Concepción, Sevilla, Spain); 2–3) copper javelin-heads (dolmen of la Pastora, Castilleja de Guzmán, Sevilla, Spain); 4) ‘Alcalar’ arrowheads (Alcalar tholos 1, Portugal); 5) ivory comb (grave 12 of Los Millares, Santa Fé de Mondujar, Almeria, Spain); 6) ivory ‘sandal’ (grave 12 of Los Millares, Santa Fé de Mondujar, Almeria, Spain) (after Leisner & Leisner Reference Leisner and Leisner1943; Almagro Basch Reference Almagro Basch1962; E. Conlin in Garcia Sanjuan et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Luciañez Triviño, Schuhmacher, Wheatley and Banerjee2013a).

Figure 3 Map of the Iberian Chalcolithic sites mentioned in the text (the mega-site of Valencina de la Concepción includes several monuments: Montelirio tholos, megalithic monument 10042-10049 (PP4-Montelirio sector), Cerro de la Cabeza, Pastora dolmen, Ontiveros dolmen) (map by I. Carrère).

An important corpus of archaeological data, therefore, seems to indicate that during the development of the southern Iberian Chalcolithic, foreign materials and prototypes were imported, including ivory from Asia and Africa, and probably amber from Sicily (Nocete et al. Reference Nocete, Vargas, Schuhmacher, Banerjee and Dindorf2013; Luciañez Triviño & García Sanjuán Reference Luciañez Triviño and García Sanjuán2016; Murillo Barroso Reference Murillo Barroso2016b). These materials were processed locally by highly specialised craftspeople. The idea that some of these specialists may have been of Levantine, Egyptian or African origin cannot be discounted. Indeed, if the rulers of Near Eastern city-states called in the most renowned craft workers to process lapis lazuli, ivory, bronze and faïence, why should the situation have been different in southern Iberia? Recent research suggests the important role that craft specialisation may have played at sites such as Valencina de la Concepción (García Sanjuán et al. Reference García Sanjuán, Vargas Jimenez, Hurtado Perez, Ruiz Moreno and Cruz-Auñon Briones2013b). The discoveries made in the tholos of Montelirio and in the megalithic monument 10042-10049 of the PP4-Montelirio sector have radically altered perception of the Chalcolithic of this region (Fernandez Flores et al. Reference Fernandez Flores, García Sanjuán and Díaz-Zorita Bonilla2016). Most obviously, socially dominant individuals can be clearly identified through the quantity and the quality of the materials and objects in their tombs: the Montelirio tholos included the largest quantities of ivory and amber of all Iberian sites. Was Valencina a ‘hub’ for receiving and processing Asian and African materials? While the idea of a movement from the Aegean-Anatolian region long prevailed (the ‘colonies’ of E. Sangmeister and B. Blance; Blance Reference Blance1961, Reference Blance1971; Sangmeister Reference Sangmeister1975), these concepts have been progressively challenged in favour of purely autochthonous developments (Renfrew Reference Renfrew1967; Guilaine Reference Guilaine1994). Without ignoring indigenous creativity, it is clear that Levantine and Egyptian impetus influenced the social development of southern Iberia, particularly in relation to the emergence of a hierarchy on the importation of exotic goods.

With regard to these observations it may be noted that, in the early twentieth century, the Belgian archaeologist Luis Siret (Reference Siret1913) compared several Iberian Chalcolithic cultural traits with those from Egypt—notably the ‘symbolic’ hoes (funerary adzes), figurines, ivory combs, ostrich eggs, alabaster vases and hippo ivory, as well as lithic artefacts (Siret Reference Siret1913: fig. 6; Chapman Reference Chapman1990) (Figure 4). A century later, the archaeological record seems to confirm, at least partially, Siret’s intuition.

Figure 4 Comparison of objects recorded at Chalcolithic sites in the southern part of the Iberian peninsula, and vestigial remains stemming from Egypt and the Aegean (after Siret Reference Siret1913: fig. 6).

The emergence of the Maritime Bell Beaker tradition

Despite increased research, the long-standing debate around the emergence of the Maritime Bell Beaker tradition remains unresolved. Here, I propose a further hypothesis resulting from the evidence discussed above. The Bell Beaker phenomenon is generally considered to have originated in two main areas: Northern and Central Europe, and southern Iberia. Research in the former area has advanced a direct link between Corded Ware groups and the emergence of Bell Beakers. The model of continuous ceramic development (Protruding-Foot (PF)/All-Over-Ornamented (AOO)/Maritime/Veluwe beakers) proposed for the Netherlands (Lanting & van der Waals Reference Lanting and van der Waals1976; van der Waals Reference van der Waals1984), for example, is not strictly confirmed by a recent re-examination of the radiocarbon data (Beckerman 2011–Reference Beckerman2012). More particularly, dating of the AOO beakers, considered a transitional form between the PF and Maritime beakers, was not ascertained by this study. Although there are temporal overlaps between the PF, AOO and Maritime beakers, the latter cannot date earlier than 2500 BC; they are rarely encountered and hardly support the identification of Northern Europe as an area of Corded Ware to Bell Beaker succession. A stronger argument in favour of such a succession comes from the similarities in the shapes of Corded Ware and Bell Beaker common wares (Besse Reference Besse2003). Moreover, Central European models may have inspired the practice of individual burials beneath mounds and the strict gendered rules with regard to the orientation of the body (although differing between the cultures). This hypothesis therefore considers the Bell Beaker expansion as a progression from Northern and Central Europe towards the Atlantic coast and the Mediterranean, introducing Bell Beaker funerary practices into Western and Southern Europe hitherto characterised by collective burials.

The other theory refers to a Mediterranean—and predominantly a southern Iberian—origin, encompassing Andalusia and the Lisbon bay area (Schmidt Reference Schmidt1913; Bosch Gimpera Reference Bosch Gimpera1926; Del Castillo Yurrita Reference del Castillo Yurrita1928; Sangmeister Reference Sangmeister1963). This hypothesis states that distinct elements (e.g. copper tongue daggers, turtle-shaped buttons, Palmela arrowheads) of the Bell Beaker ‘package’, which accompanies the diffusion of the bell-shaped beakers, have a near-certain Iberian origin, given that copper metallurgy was notably developed in Iberia during the late fourth millennium BC. A potential origin of the Maritime beaker from the ‘copos’ (beakers) of the Portuguese horizon Vila Nova de São Pedro I is also taken into account on the basis of technical similarities in decoration (Harrison Reference Harrison1977), despite remaining differences. In addition, radiocarbon dates potentially further support an Iberian origin, although some of the early dates (from the twenty-seventh century BC onwards) await confirmation (Cardoso Reference Cardoso2014).

Nonetheless, the origin of Maritime beakers still requires explanation. In my opinion, this form represents the earliest manifestation of the Beaker phenomenon. It also constitutes the broadest geographic expansion across the continent and serves as a diagnostic for the Bell Beaker community or koine. As early as the fourth millennium BC, many European cultures were innovative in producing beakers and jugs following regionally specific forms (Guilaine Reference Guilaine2009). In contrast, the obliquely impressed patterns characteristic of the Maritime beaker are not associated with any clearly identified European tradition. The only other regions in which comb impressions, arranged in horizontal bands with the oblique lines, attested prior to the Bell Beaker ware are Tiout in Algeria and El Kiffen in Morocco (Bailloud & Mieg de Boofzheim Reference Bailloud and Mieg de Boofzheim1964; Camps-Fabrer Reference Camps-Fabrer1966). Given the geographic proximity between North Africa and Iberia, processes of technological transfer between these two spheres cannot be excluded, especially as materials reached Southern Europe from more distant parts of Africa.

This, however, does not explain the reasons for the ‘emergence’ of beakers with zoned decoration as a marker of social status. This also explains why I do not exclude Maritime beakers—through analogy with the various regional Chalcolithic examples of ‘noble’ exotic materials (e.g. the ivory and amber items from the Montelirio tholos and the megalithic monument 10042-10049)—which were perceived as status symbols among the elites due to their innovative aesthetics. Regardless of the function of the Maritime beaker, a suitable social context favouring its emergence and adoption was required in order to distinguish such a marker. In the whole of third-millennium BC Western Europe, only one region benefited from such a social environment: southern Iberia, with its unusually large sites and burials probably restricted to high-ranking leaders. A possible hypothesis could be that these elites may have called in potters (perhaps from Africa) to produce such an original beaker type, which may also have been the expression of a particular social group. This situation would then explain the strong and expanding presence of this marker within the existing material cultural tradition (from Almeria to Lisbon Bay), which would become completely different from that of the Iberian interior. The end of the regional Chalcolithic—marked by the progressive abandonment of its most characteristic sites—was not due to any external intrusion. Rather, the internal evolution of this society, driven by specific Bell Beaker development, finally led to its deconstruction.

The points presented above can therefore be summarised as follows:

1) Stelae iconography mirrors an ideology (i.e. armed males) that characterised various European cultures as early as the fourth millennium BC, at a time when daggers with flint or copper blades became common in Western Europe (Guilaine & Zammit Reference Guilaine and Zammit2005).

2) The latest research on southern Iberia allows for the description of a specific, regional cultural setting, in which the elite had access to exotic materials and to cultural influences originating in the Eastern Mediterranean. The influence of the steppes is therefore, in my opinion, not key to the debate.

3) The hypothesis proposing the emergence of Maritime beakers in southern Iberia is not a new one. It may, however, be reinvigorated through consideration of the evidence of the unique early third-millennium BC social context of the region within Europe at this time, in terms both of the power of its connections and of its actors.

Acknowledgements

Karoline Mazurié de Keroualin translated this manuscript from French.