Introduction

Treatment approaches that include strategies for cognitive change, such as cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT), are commonly recommended for the treatment of psychopathology in children and adolescents. Indeed, there is increasing evidence for the short- and long-term efficacy of CBT for a range of difficulties in childhood and adolescence (e.g. Schmidt et al., Reference Schmidt, Lee, Beecham, Perkins, Treasure, Yi, Winn, Robinson, Murphy, Keville, Johnson-Sabine, Jenkins, Frost, Dodge, Berelowitz and Eisler2007; Smith et al., Reference Smith, Yule, Perrin, Tranah, Dalgleish and Clark2007). However, while many young people treated with CBT experience clinically and statistically significant improvements, a large number of clients continue to present with symptoms post-treatment (e.g. Cartwright-Hatton, Roberts, Chitabesan, Fothergill and Harrington, Reference Cartwright-Hatton, Roberts, Chitabesan, Fothergill and Harrington2004).

The effectiveness of CBT for young people depends on a broad range of factors. Client-, clinician-, and treatment-related variables (specific and non-specific) all potentially predict treatment response in child and adolescent psychotherapy (March and Curry, Reference March and Curry1998). One likely cause of poorer treatment outcomes is a mismatch between the type or level of treatment provided, and the client's CBT-relevant cognitive capacitiesFootnote 1. Researchers and clinicians commonly make reference to the importance of cognitive capacities such as abstract reasoning, cognitive flexibility, and psychological mindedness for young people's engagement in CBT (e.g. Holmbeck, O'Mahar, Abad, Colder and Updegrove, Reference Holmbeck, O'Mahar, Abad, Colder, Updegrove and Kendall2006; Quakley, Reynolds and Coker, Reference Quakley, Reynolds and Coker2004; Sauter, Heyne and Westenberg, Reference Sauter, Heyne and Westenberg2009). These capacities allow young people to identify and discriminate their own thoughts, feelings, and behaviours, and to objectively identify causal relations between them. Indeed, such cognitive capacities are seen to be important for successful engagement in cognitive therapeutic strategies, such as the identification, refutation, and adaptation of maladaptive cognitions (Doherr, Reynolds, Wetherl and Evans, Reference Doherr, Reynolds, Wetherly and Evans2005; Grave and Blissett, Reference Grave and Blissett2004). While several studies have demonstrated that even children as young as 5 years can engage in some meta-cognitive tasks (Flavell, Green and Flavell, Reference Flavell, Green and Flavell2000; Quakley, Coker, Palmer and Reynolds, Reference Quakley, Coker, Palmer and Reynolds2003), there are likely to be considerable intra- and inter-individual differences in the development of these cognitive capacities (Bacow, Pincus, Ehrenreich and Brody, Reference Bacow, Pincus, Ehrenreich and Brody2009; Holmbeck et al., Reference Holmbeck, O'Mahar, Abad, Colder, Updegrove and Kendall2006).

Psychological mindedness (PM) is a cognitive capacity that has long been regarded as having an influence on treatment outcome. It is generally seen as a (meta)cognitive construct involving the awareness and understanding of psychological phenomena such as cognitions, emotions, and behaviours of oneself and others (Farber, Reference Farber1985; Hatcher, Hatcher, Berlin, Okla and Richards, Reference Hatcher, Hatcher, Berlin, Okla and Richards1990). Clients high in PM are held to be more observant of the relations between cognitive, affective, and behavioural states, and therefore more able to participate in psychotherapeutic interventions (Beitel, Ferrer and Cecero, Reference Beitel, Ferrer and Cecero2005; Farber, Reference Farber1985). Indeed, McCallum, Piper, Ogrodniczuk and Joyce (Reference McCallum, Piper, Ogrodniczuk and Joyce2003) found a significant relation between PM and outcomes in both short-term group psychotherapy for grief (n = 107) and short-term individual psychotherapy for clients with mixed diagnoses (n = 144). Similarly, Conte et al. (Reference Conte, Plutchick, Jung, Picard, Karasu and Lotterman1990) reported a positive relation between PM and treatment outcome in a sample of 44 adults with affective disorders, although they failed to replicate these results in a later study (Conte, Ratto and Karusa, Reference Conte, Ratto and Karusa1996).

While these adult-based studies support the notion that clients high in PM respond better to treatment than less psychologically minded clients, there has been very little systematic exploration of PM in relation to CBT with young people. This is despite the fact that PM may be particularly relevant to engagement in CBT, given that CBT encourages the monitoring, evaluation and expression of cognitions, emotions, and behaviours (Grant, Reference Grant2001). In the one study to date, Boylan (Reference Boylan2006) compared CBT for depression in adolescents (n = 37) with Systemic-Behavioural Family Therapy (n = 35) and Non-Specific Treatment (n = 35). Levels of PM were not found to be predictive of post-treatment functioning (e.g. depression as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory). At the same time, clients with high PM showed a more rapid improvement in the CBT condition in comparison to those treated with Systemic-Behavioural Family Therapy.

Valid and reliable measures may allow for further exploration of the relationship between cognitive capacities such as PM and CBT outcomes with children and adolescents. Until recently, measures of PM and related constructs (e.g. self-consciousness) were not without problems. In particular, there had been a tendency for measures of PM to tap into maladaptive cognition such as rumination (Kingree and Ruback, Reference Kingree and Ruback1996). For example, items of the Private Self-Consciousness Scale (PrSCS; Fenigstein, Scheier and Buss, Reference Fenigstein, Scheier and Buss1975) have been shown to correlate significantly with measures of depressive psychopathology, and these items may therefore fail to accurately capture the type of PM that is seen to be essential for engagement in CBT (Anderson, Bohon and Berrigan, Reference Anderson, Bohon and Berrigan1996).

An alternative framework with which to understand PM and its potential relevance to CBT is encapsulated in the multidimensional model of PM developed by Grant (Reference Grant2001)Footnote 2. Grant positioned PM as a (meta)cognitive construct incorporating both: (1) the capacity to explore cognitive, affective, and behavioural phenomena (self-reflection); and (2) an interest in, and understanding of, cognitive, affective, and behavioural phenomena (insight). The process by which individuals monitor (i.e. self-reflect) and evaluate (i.e. apply insight to) the impact of cognitive, affective, and behavioural changes is seen to be particularly relevant to the clinical practice of CBT (Grant, Reference Grant2001). For example, Grant noted that the process of self-refection is akin to the self-monitoring held to be central to CBT, and suggested that the speed or extent of a client's response to CBT may be influenced by their level of self-reflection and insight. Further, Grant also suggested that a knowledge of the capacity for self-reflection and insight can be used to guide clinicians’ use of cognitive and behavioural techniques.

In order to facilitate tests of this model of PM, Grant, Franklin and Langford (Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002) developed and evaluated the Self-Reflection and Insight Scale (SRIS) for use with adults. The Insight subscale of the SRIS (SRIS-IN) was found to demonstrate good convergent and divergent validity, in that it was negatively associated with measures of psychopathology and positively associated with a measure of cognitive flexibility. The Self-Reflection subscale (SRIS-SR) was positively correlated with a measure of anxiety, which was seen to indicate a possible overlap with rumination. In a more recent study by Roberts and Stark (Reference Roberts and Stark2008), exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of the SRIS administered to a sample of medical students (n = 462) suggested that three factors best fit the data: two self-reflection subscales (Engagement in Self-Reflection and Need for Self-Reflection) and an Insight subscale. While Grant and colleagues (Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002) found no gender effects, Roberts and Stark (Reference Roberts and Stark2008) reported that males scored higher on the Insight subscale relative to females, and they found a positive correlation between age and Insight. The findings reported by Grant and colleagues (Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002) and Roberts and Stark (Reference Roberts and Stark2008) provide confirmation of both the content and construct validity of the SRIS. Both research teams concluded that further research is needed to explore the predictive validity of the measure. Nonetheless, based on the encouraging findings, Grant and colleagues (Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002) concluded that the SRIS can be regarded as an “advance” on other measures of PM, in that it allows for the examination of self-reflection and insight as two distinct components of PM (2002, p. 833).

In summary, self-reflection and insight are two cognitive capacities relevant to the practice of CBT, including the practice of CBT with young people. A major emphasis in the clinical and research literature on CBT with young people is the need to consider the influence of CBT-relevant cognitive capacities on engagement in treatment (Grave and Blissett, Reference Grave and Blissett2004; Quakley et al., Reference Quakley, Reynolds and Coker2004). In order to facilitate research into the relationship between self-reflection, insight, and the outcomes of CBT with young people, an empirically-tested measure of self-reflection and insight in young people is required. The aim of the current study was to translate and adapt the SRIS for use with a child and adolescent population. Study 1 focused upon the adaptation of the adult measure for use with young people, including piloting to test the comprehensibility of the adapted measure (Self-Reflection and Insight Scale for Youth; SRIS-Y). Study 2 explored the psychometric properties of the SRIS-Y in a community sample, including evaluation of its reliability and structural, convergent, and divergent validity. Based on the findings associated with the adult measure (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002; Roberts and Stark, Reference Roberts and Stark2008), it was expected that the structural, convergent, and divergent validity of the SRIS-Y would be adequate. Age and gender trends in self-reflection and insight were analyzed exploratively.

Study 1: Development of the SRIS for a Dutch child and adolescent population

Method

Participants

One hundred and thirty-eight children and adolescents (60 boys and 78 girls), aged 9 to 18 years (M = 13.83 years, SD = 2.68) participated in Study 1. These young people were drawn from primary schools (n = 58) and secondary schools (n = 80) in the region South Holland, the Netherlands. Almost the entire sample was of Dutch origin (94.2%).

Procedure

Permission to translate and adapt the SRIS was granted by the original author prior to commencing the study. The English version of the SRIS was translated according to guidelines for the translation of instruments in cross-cultural research (van Widenfelt, Treffers, de Beurs, Siebelink and Koudijs, Reference van Widenfelt, Treffers, de Beurs, Siebelink and Koudijs2005). Items that were seen to contain difficult words (e.g. aware of; reflect) or to have a complex sentence structure were adapted so as to be more suitable for use with children and adolescents. An example of an adapted SRIS-Y item included “I usually notice that I have thoughts” (original: I am usually aware of my thoughts). To further increase the developmental appropriateness of the questionnaire, a practice item was added to allow respondents to gain familiarity with the response format.

The study was carried out with the approval of the Psychology Ethics Committee of the University. Permission to conduct the study was received from school principals, and parental and child consent was obtained. A randomly selected subset of participants (n = 34) answered a number of piloting questions following completion of the questionnaire in the classroom in order to assess the comprehensibility of the items. Two questions were posed in relation to each item in the questionnaire: “Did you understand the question?” (yes; a little; not at all), and “Did the item contain any difficult words?” (none were difficult; some were difficult; all were difficult). Participants were also asked: “Did you understand the instructions?” (yes; a little; not at all).

Instrument

The Self-Reflection and Insight Scale (SRIS; Grant et al., Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002) is a 20-item self-report instrument that comprises two subscales: Self-Reflection and Insight. The SRIS assesses individuals’ propensity to reflect on, and their level of insight into, their thoughts, feelings, and behaviour. Items are answered with a 6-point scale (1 = disagree strongly to 6 = agree strongly). The authors reported that the SRIS is a valid and reliable measure of self-reflection and insight in adults (Cronbach's α SRIS-SR = .91 and Cronbach's α SRIS-IN = .87). The test-retest reliability was .77 for the Self-Reflection subscale and .78 for the Insight subscale.

Data analysis

Two cases with more than 25% of items missing on the SRIS-Y questionnaire were excluded from analyses. The remaining missing values (17 participants had 1 item missing) were replaced by extrapolated values using the person mean substitution method (Hawthorne and Elliott, Reference Hawthorne and Elliott2005). The responses to the piloting questions were examined to determine whether the SRIS-Y items were comprehensible. The internal consistency of the questionnaire was assessed with the Cronbach's alpha statistic (acceptable ≥.70; Field, Reference Field2005). SRIS-Y items were assessed with respect to means, standard deviations, floor and ceiling effects, the proportion of participants with a missing value on an item, and the skewness and kurtosis of the item response distribution. Items should be restructured or removed if they show extreme skewness and/or kurtosis (i.e. less than -1 or more than 1; Noom, Deković and Meeus, Reference Noom, Deković and Meeus2001). In addition, item-total correlations were examined to check for homogeneity of the scale. If items correlate less than .15 with the total test score, it is likely that they do not measure the same construct as the scale and may need restructuring (Field, Reference Field2005).

Results

Piloting

T-tests revealed no significant differences on total and subscale scores between the total sample and the final piloting sub-sample (all p's >.15). Analyses of the piloting data revealed that 85.6% of the participants did not find any of the words in the items of the SRIS-Y to be “difficult”. Of the respondents reporting difficulties, the words “reflect” (Item 16), “evaluate” (Item 5), “analyze” (Item 2), and “self-reflection” (Item 8) were most often cited. Relative to the older participants (14–18 years), the younger participants (9–13 years) rated the items of the questionnaire as more difficult to comprehend, t(31.61) = 2.06, p = .05, and had more trouble understanding the instructions, t(29.94) = 2.22, p = .03.

Internal validity and item analysis

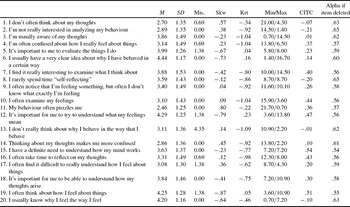

The Cronbach's α for the whole questionnaire was .60. Item response statistics and item-total correlations are displayed in Table 1. For all but one item (Item 13), there was a low rate of non-response, indicating good comprehensibility of the questionnaire. There was a broad range of responses for the SRIS-Y items, with low rates of floor and ceiling effects. The majority of items (16 out of 20) demonstrated acceptable skewness and kurtosis, and 14 items correlated adequately with the total score.

Table 1. Item response statistics of the SRIS-Y, n = 138

Note. SRIS-SR = Self-Reflection subscale; SRIS-IN = Insight subscale.

M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation; Mis. = Proportion of participants with any item missing on the scale; Skw. = Skewness; Krt. = Kurtosis; Min/Max = % Responses in minimum/maximum response category; CITC = Corrected item-total correlation

Discussion

Overall, the majority of the items of the SRIS-Y posed no difficulty for the participants. Younger participants reported more problems than their older counterparts. While the scale had a less than adequate internal consistency (Field, Reference Field2005), the item response descriptives derived from Study 1 demonstrated that the SRIS-Y is a psychometrically adequate measure. It was anticipated that adaptations to the items deemed to be problematic would result in better comprehensibility, and enhanced psychometric properties of the SRIS-Y.

Study 2: Evaluation of the psychometric properties of the SRIS-Y

Method

Participants

The final sample in Study 2 consisted of 215 children and adolescents (102 boys and 113 girls), aged 9 to 17 years (M = 13.66 years, SD = 2.23). The participants attended urban and rural schools in the region South Holland, the Netherlands. Most were of Dutch origin (93.5%). The sample included 82 participants from primary school and 133 participants from secondary school.

Procedure

Feedback from the Study 1 participants led to the inclusion of a definition of “self-reflection” in the introduction to the questionnaire. The responses to the piloting questions and the results of the item response analyses in Study 1 led to the restructuring and adaptation of several items in an effort to improve the internal consistency of the questionnaire (Table 2). In addition, the readability of the new questionnaire was assessed according to Dutch reading grade levels (van den Berg and te Lintelo, Reference Van Den Berg and te Lintelo1977) and was found to be suitable for young people from Grade 6 and older.

Table 2. Adaptations to items based on the results of Study 1

Note. All items with R are reverse scored. Items 1, 10, 14 and 20 were not restructured for reasons concerning the content of the item.

Study 2 was carried out with the approval of the Psychology Ethics Committee of the University. Permission to conduct the study was received from school principals, and parental and child consent was obtained. The participants completed the questionnaire package in their classroom.

Instruments

To explore the convergent validity of the final version of the SRIS-Y, two additional measures of CBT-relevant cognitive capacities were administered. The first capacity, abstract reasoning, was assessed via the Shipley Institute of Living Scale – Abstraction Subscale (SILS; Shipley, Reference Shipley1940; Dutch translation and adaptation by Schmand and Smeding, Reference Schmand and Smeding2000). The SILS consists of 20 incomplete sequences of numbers, letters, or words that are completed by the participants. Good test-retest reliability, validity, and internal consistency have been reported in research using the SILS. In the current study, the Cronbach's α for the SILS was good (α = .80). The second capacity, cognitive flexibility, was assessed via the Cognitive Flexibility Scale (CFS; Martin and Rubin, Reference Martin and Rubin1995). The CFS assesses an individual's flexibility in thinking, decision-making, and problem-solving on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree). The authors of the instrument reported good internal consistency (.76), test-retest reliability (.83), and construct and concurrent validity. In the current study a shortened version was used so that the entire test battery could be completed during one school lesson. Six items of the CFS that were seen to be most relevant to cognitive development (i.e. they addressed thinking and problem-solving) were translated and adapted for use with Dutch children and adolescents (Sauter and Heyne, Reference Sauter and Heyne2007). In the current study, the Cronbach's α for the six items of the CFS was .48.

To explore the divergent validity of the SRIS-Y, the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, Reference Goodman1997; Dutch translation and adaptation by van Widenfelt, Goedhart, Treffers and Goodman, Reference van Widenfelt, Goedhart, Treffers and Goodman2003) was administered. The SDQ is a 25-item questionnaire that assesses the psychosocial adjustment of children and adolescents. For the purposes of this study, the 5-item Emotional Symptoms subscale was used as an index of internalizing problems. Previous studies using the SDQ have reported adequate psychometric properties (van Widenfelt et al., Reference van Widenfelt, Goedhart, Treffers and Goodman2003). In the current study, the Cronbach's α for the Emotional Symptoms subscale of the SDQ was satisfactory (α = .77).

Data analysis

Prior to data analysis, five cases with more than 25% of the items of a measure missing were excluded from the data set. Two further cases with more than 10 items missing across all questionnaires were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 215 cases. For cases with ≤3 items missing on the questionnaires (SRIS, n = 18; CFS, n = 6; SDQ, n = 19), values to replace missing values were extrapolated using the person mean substitution method (Hawthorne and Elliott, Reference Hawthorne and Elliott2005). Because the SRIS-Y was an adult measure adapted for use with a child and adolescent population, exploratory factor analysis was deemed the most suitable method of assessing its structural validity. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure and Bartlett's Test of Sphericity were calculated to examine the suitability of the data for conducting a principal component analysis with varimax rotation. The scree-plot was used to determine how many components to retain (Stevens, Reference Stevens2002). Internal consistency was assessed with the Cronbach's alpha statistic for the total scale as well as for the resulting factors. Subscale-total correlations and inter-subscale correlations were calculated, as well as the skewness and kurtosis of the items. Convergent and divergent validity was examined using correlation coefficients between scores on the SRIS-Y and measures of CBT-relevant cognitive capacities (i.e. the CFS and SILS), and scores on the SDQ respectively. Age trends and gender-related trends in the data were explored using t-tests and correlations. For the age-related analyses, the sample was divided into two groups, namely childhood to early adolescence (8–13 years; n = 110) and mid- to late adolescence (14–18 years; n = 105).

Results

Due to time limitations, a number of participants did not complete all measures included in the package (n = 93). T-tests revealed no significant differences on questionnaire scores between the group of participants that completed all measures, and those who did not (all p's >.12). Therefore, cases were excluded pairwise to allow for the maximum number of respondents in the analyses. The number of cases in each analysis is presented in Table 4.

Principal component analysis

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure (.86) and Bartlett's Test χ2(190, n = 215) = 1071.24, p <.01 confirmed that the data were suitable for conducting a principal component analysis (PCA). Four factors were found with eigenvalues greater than 1, but inspection of the scree plot revealed two factors above the point of inflexion. These two factors accounted for 39.3% of the total variance. After varimax rotation, factor loadings were all greater than or equal to 0.40, with the exception of two items (Items 5 and 6). The two factors reflected constructs similar to the Self-Reflection and Insight factors reported in the Grant et al. (Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002) study. The first factor included all 12 of the items from the original Self-Reflection subscale. The second factor comprised seven of the eight items from the original Insight subscale. One item (Item 3) from the Insight subscale loaded on the first factor, rather than on the second factor.

After removing Item 3 and the two items with a factor loading <.40, a second principal component analysis with varimax rotation was conducted. The results of the analysis are shown in Table 3. This time, the two factors accounted for 43.1% of the total variance, and the factors were in keeping with the subscales of the original questionnaire. The alpha for the whole scale was .77. The alphas for the subscales are presented in Table 3. Separate factor analyses were also carried out with the two age groups (8–13 years and 14–18 years) to verify the consistency of the factor structure. Each analysis yielded a two factor solution in which the Self-Reflection and Insight subscales comprised exactly the same items as found for the group as a whole.

Table 3. Factor loadings and Cronbach's Alphas for the SRIS-Y subscales (n = 215)

Note. All items with R are reverse scored. Factor loadings above .40 appear in bold.

Examination of the skewness and kurtosis of the 17 items revealed two items with slightly elevated negative kurtosis (Item 16 kurtosis = –1.07; Item 9 kurtosis –1.06). It was decided to retain these items since these were regarded as essential to the scale. Correlations between the SRIS-Y total score and each of the factors yielded the following: Self-Reflection (r = .82, p <.01), and Insight (r = .48, p <.01). There was a non-significant negative correlation between the Self-Reflection and the Insight factors.

Convergent and divergent validity

To investigate convergent validity, scores on the SRIS-Y subscales were correlated with scores on the CFS and SILS (Table 4). As expected, scores on the Self-Reflection subscale and the Insight subscale correlated moderately and significantly with scores on the CFS. No significant associations were found between scores on the SRIS-Y subscales and the SILS. With respect to divergent validity, scores on the Self-Reflection subscale were positively correlated with scores on the Emotional Symptoms subscale of the SDQ (Table 4). The Insight subscale and the Emotional Symptoms subscale were negatively correlated.

Table 4. Correlations between SRIS-Y subscales, measures of cognitive capacities and an index of internalizing problems

Note: SRIS-SR = Self-Reflection subscale; SRIS-IN = Insight subscale; CFS = Cognitive Flexibility Scale (n = 215); SILS = Shipley Institute of Living Scale – Abstraction Subscale (n = 119); SDQ = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (n = 205)

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

Gender and age trends in self-reflection and insight

On average, girls scored higher on the Self-Reflection subscale relative to boys, t(213) = –2.79, p <.01. There were no significant gender differences on the Insight subscale. No age effects were found when younger (8–13 years) and older (14–18 years) participants’ subscale scores were compared in a t-test. Closer inspection of the two age groups revealed a weak but significant correlation between age and Self-Reflection subscale scores in the 14–18 year age group (r = .31, p <.01, n = 105).

Discussion

An initial exploratory factor analysis identified three poorly functioning SRIS-Y items. One of these items (Item 3: “I usually notice my thoughts”) was also found to be a problematic item in the studies by Grant et al. (Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002) and Roberts and Stark (Reference Roberts and Stark2008). The three items were removed and a second PCA was conducted. Unlike Roberts and Stark (Reference Roberts and Stark2008), who found that a three-factor solution was the best fit, we found two factors that mirrored the Self-Reflection and Insight subscales of the adult SRIS (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002). There was a non-significant negative correlation between the two factors, echoing the results of the study by Grant and colleagues (Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002). The internal consistency of the SRIS-Y in Study 2 was considerably higher than in Study 1, and was comparable to the adult SRIS (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002), and to other measures of psychological mindedness for adolescents (e.g. Boylan, Reference Boylan2006).

The convergent validity of the SRIS-Y was supported by the associations with items from a measure of cognitive flexibility (CFS), also used in Grant and colleagues’ (Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002) evaluation of convergent validity. As Grant and colleagues (Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002) found that only Insight scores correlated positively with CFS scores, the findings of the current study may reflect either the exclusion of a number of the CFS items in the current study, or the application of the measure with a younger, Dutch population. Contrary to expectations, there was no relationship between scores on the Insight subscale and a measure of abstract reasoning (SILS), which may indicate that these are non-overlapping cognitive capacities. This interpretation was also noted in a study by Hatcher and colleagues (Reference Hatcher, Hatcher, Berlin, Okla and Richards1990), who reported complex patterns of correlations between scores on measures of abstract reasoning and psychological mindfulness.

Study 2 provided support for the divergent validity of the SRIS-Y. Mirroring the results of Grant et al. (Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002), a negative correlation was found between the Insight subscale and an index of internalizing problems. This suggests that the Insight subscale may indeed be measuring psychologically adaptive self-awareness. Similar results have been reported in adult populations using related measures of insight (e.g. the Internal State Awareness subscale of the PrSCS; Kingree and Ruback, Reference Kingree and Ruback1996). As in Grant and colleague's (Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002) study, a positive association was found between the Self-Reflection subscale and an index of internalizing problems. While the aim of the SRIS was to measure constructive rather than dysfunctional self-reflection, it seems that the Self-Reflection subscale may measure a ruminative self-focus, which is associated with emotional symptoms both in adults and in young people.

Girls scored significantly higher than boys on the Self-Reflection subscale. Although this finding contrasts with the results of Grant et al. (Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002) and Roberts and Stark (Reference Roberts and Stark2008), it is in line with studies into various PM-related constructs in adults, which report that females are generally more open to introspection (e.g. Csank and Conway, Reference Csank and Conway2004). The presence of gender differences in rumination from as early as 12 years of age (Jose and Brown, Reference Jose and Brown2008) may also contribute to the relationship between gender and the Self-Reflection subscale found in the current study.

Age-related trends in self-reflection were only found in young people aged 14 to 18 years. These results seem to indicate that the development of self-reflection skills may intensify in mid- to late adolescence, rather than there being a linear progression in skill development. This is in contrast to the findings of research into the related construct of PM, which suggest that PM continues to develop throughout adolescence (Hatcher et al., Reference Hatcher, Hatcher, Berlin, Okla and Richards1990). The lack of age effects on the Insight subscale may reflect the notion that insight is an individual disposition, rather than a capacity that ripens over time. Indeed, the development of insight may be unrelated to the development of self-reflection.

General discussion

The results of the present study suggest that the SRIS-Y, a measure of self-reflection and insight adapted for use with children and adolescents, is applicable with young people and is psychometrically adequate. Study 1 involved the adaptation of the adult SRIS to make it suitable for a younger age group. Overall, the items of the SRIS-Y were understandable for the participants. Younger children in the sample had more problems with the measure than older participants. Use of the SRIS-Y may therefore be most appropriate with adolescents and older children. With younger children, interactive and concrete tasks aimed at measuring self-reflection and insight may be more suitable than pen-and-paper measures. A potential lead for the development of such tasks is found in the “thought/feeling/behaviour card sort task” which is aimed at assessing another CBT-relevant capacity, namely distinguishing between thoughts, feelings, and behaviours (Quakley et al., Reference Quakley, Reynolds and Coker2004).

Following modifications suggested by Study 1, Study 2 reported on the factor structure, internal consistency, and validity of the SRIS-Y. In addition, gender and age trends in SRIS-Y scores were also explored. Similar to the results of the factor analysis reported by Grant et al. (Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002), the SRIS-Y was found to comprise two non-correlated and internally consistent subscales measuring self-reflection and insight. Support for the convergent validity of the SRIS-Y subscales was evidenced by associations with a measure of a CBT-relevant cognitive capacity, corresponding with findings from the evaluation of the adult SRIS (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Franklin and Langford2002). Divergent validity was demonstrated for the Insight subscale, but not for the Self-Reflection subscale. Rather than using the whole SRIS-Y as a measure of “adaptive” self-reflection, the Insight subscale may provide the best estimate of the type of cognitive capacities most relevant to participation in CBT.

The findings of the current study are promising with respect to the administration of the SRIS-Y with children and adolescents, but several limitations warrant consideration. In terms of the sample, the majority of the participants were of Dutch origin, and therefore the reliability and validity of the SRIS-Y when applied in more diverse populations or in other cultures and countries requires investigation. Second, the generalizability of the findings to a clinical sample is uncertain, given that the current study made use of a community sample of young people with low levels of self-reported psychopathological symptoms. Third, the deletion of several items following the exploratory factor analysis may have influenced the content validity of the measure, calling for further examination of the structural and convergent validity of the 17-item version of the SRIS—Y.

The results of the present research have both research and clinical implications. Following the work of Roberts and Stark (Reference Roberts and Stark2008), confirmatory factor analyses can be conducted to clarify whether a two or three factor structure best fits data gathered via the SRIS-Y. Further, convergent validity can be re-assessed using other measures of PM and, given the low Cronbach's alpha's in the current study, the full version of the CFS. Finally, research should investigate the relationship between self-reflection, insight, and measures of rumination, given that the current study provides evidence for a link between the Self-Reflection subscale and internalizing problems. Researchers can begin to assess the predictive validity of self-reflection and insight in young people, relative to other possible predictors of treatment response, in order to better understand the mediating or moderating role that such cognitive capacities may have during treatment. For clinicians, client responses to the SRIS-Y may provide an indication of the extent to which the young person is able to engage in behavioural and cognitive therapeutic interventions such as CBT. Clinicians may choose to adapt the delivery or timing of cognitive therapeutic interventions based on their knowledge of available self-refection and insight skills. For example, young people with low levels of self-reflection and insight may benefit from additional emphasis in treatment on training in self-monitoring of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours (Sauter et al., Reference Sauter, Heyne and Westenberg2009).

In conclusion, the findings of Study 1 and Study 2 support the use of the SRIS-Y as a psychometrically sound and developmentally-appropriate measure of cognitive capacities in young people. This measure provides a much-needed means to facilitate the exploration of self-reflection and insight in children and adolescents by researchers and CBT clinicians. The administration of the SRIS-Y in both research and clinical contexts can allow for developmentally-informed treatment delivery with the aim of enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural interventions.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank Anke Goor, Brooke Lore, Ilse Gijsbertsen, and the Bachelor Research Project for their help with collecting the data used in this study.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.