Introduction

Palliative care in specialized units faces a complex psychological symptomatology that alters both the general well-being of patients and their caregivers (Kissane et al., Reference Kissane, Clarke and Street2001; Chochinov, Reference Chochinov2006; Landry et al., Reference Landry, Stendel, Landry and Raz2018). Hypnosis is now being applied in several clinical settings for the management of pain and anxiety related to invasive tests (Liossi, White & Hatira, Reference Liossi, White and Hatira2009; Brugnoli, Reference Brugnoli2016; González-Ordi, Reference González-Ordi2005; Liossi, White & Hatira, Reference Liossi, White and Hatira2009; Jensen & Patterson, Reference Jensen and Patterson2014; Alladin, Reference Alladin2012), pain management during labor and childbirth (Madden, Middleton, Cyna & Matthewso, Reference Madden, Middleton, Cyna and Matthewson2011), or for increasing satisfaction with subcutaneous venous port placement (Sterkers, Chabrol, De Troyer, Bonijol, et al., Reference Sterkers, Chabrol, De Troyer, Bonijol, Darmon and Donnez2018; Hoslin, Motamed, Maurice-Szamburski, Legoupil, Ponsa, et al., Reference Hoslin, Motamed, Maurice-Szamburskib, Legoupil, Pons and Bordenave2019).

The midline catheter (MC) is a very useful way to administer drugs to palliative care patients (Caparas & Hung, Reference Caparas and Hung2017). A MC can be used when the placement of a central venous catheter (CVC) is not possible due to the clinical situation of the patient, or with patients with difficult access to peripheral intravenous lines, or for the administration of a concrete intravenous treatment (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Little, Vinsant and Khandelwal2016).

The objective of this study is to present the use of clinical hypnosis as an intervention tool for the placement of a MC in a patient at the end of life.

Patient identification and reason for consultation

FM is a 52-year-old male diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) at the end of life. His medical history includes a diagnosis of HIV for the last 23 years. He presented with an addiction to parenteral drugs from which he had rehabilitated 10 years ago, chronic alcoholism, and mixed chronic liver disease. The functional limitations caused by dyspnea, poor medication control at home, and his high level of anxiety have required several previous hospital admissions.

Evaluation

Upon entering the PCU, FM was informed of his clinical diagnosis, prognosis, and disease evolution. He was conscious, oriented, collaborative, without alterations of thought or perception. He also had insomnia with nightmares related to choking situations. His suffering was associated with his illness and deterioration. He also exhibited high levels of anxiety, a great fear of hospitalization and death by suffocation. He rejected the MC placement procedure. The MC was the intervention tool chosen by the medical team as the most appropriate for applying intravenous drugs in order to relieve symptoms, which was the main objective of treatment for this patient. FM had had two previous attempts to place venous catheters. The first time in the operating room, several attempts were made to place a CVC, but its placement was not possible due to the uncooperative and anxious behavior of FM. During another hospital admission, an attempt was made to place a PICC with the same result. FM reported that after 50 minutes, the placement of the device was not possible. In both cases, FM could not opt for complete sedation, given the circumstances of his illness. The vasoconstriction associated with his anxiety hindered both procedures and increased FM's fear of the test. FM verbally stated that he suffered retrospective scenes of the experienced situations that increased his anxiety, and thus rejected a new attempt, although his desire was to be able to undergo the intervention to improve control of his dyspnea. These reasons led the team to work with FM on fear, anxiety control, and the improvement of communication to be able to perform the MC placement. His level of suggestibility allowed for the use of clinical hypnosis. The measurements of suffering and symptoms were very high at the time of admission but improved after the intervention, although his dyspnea worsened after the intervention in the last week of his life (See Table 1).

Table 1. Outcomes of assessment tests

Detection of Emotional Distress Scale (Maté J, Mateo D, Bayés R, et al, Reference Maté, Mateo, Bayés, Bernaus, Casas, González-Barboteo, Limonero, López-Postigo, Sirgo and Viel2009). Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS-r) (Carvajal A, Martínez M & Centeno C, Reference Carvajal, Martínez and Centeno2013). Suggestibility Inventory (SI) (González-Ordi, H & Tobal M, Reference González-Ordi and Tobal1999).

Therapeutic objectives, intervention plan and treatment

The objectives of the psychological intervention aimed toward facilitating the placement of the MC through clinical hypnosis were:

1. Control of anxiety, useful for performing needle insertion and reducing the anxiety level that hinders symptomatic control and communication;

2. Psychoeducation regarding medical procedures to be used during his hospitalization;

3. Search for confrontation strategies useful for confronting his death process;

4. Trauma management for the CVC and PICC placement attempts; and

5. Training for the needle insertion.

Hypnotic treatment for the MC placement

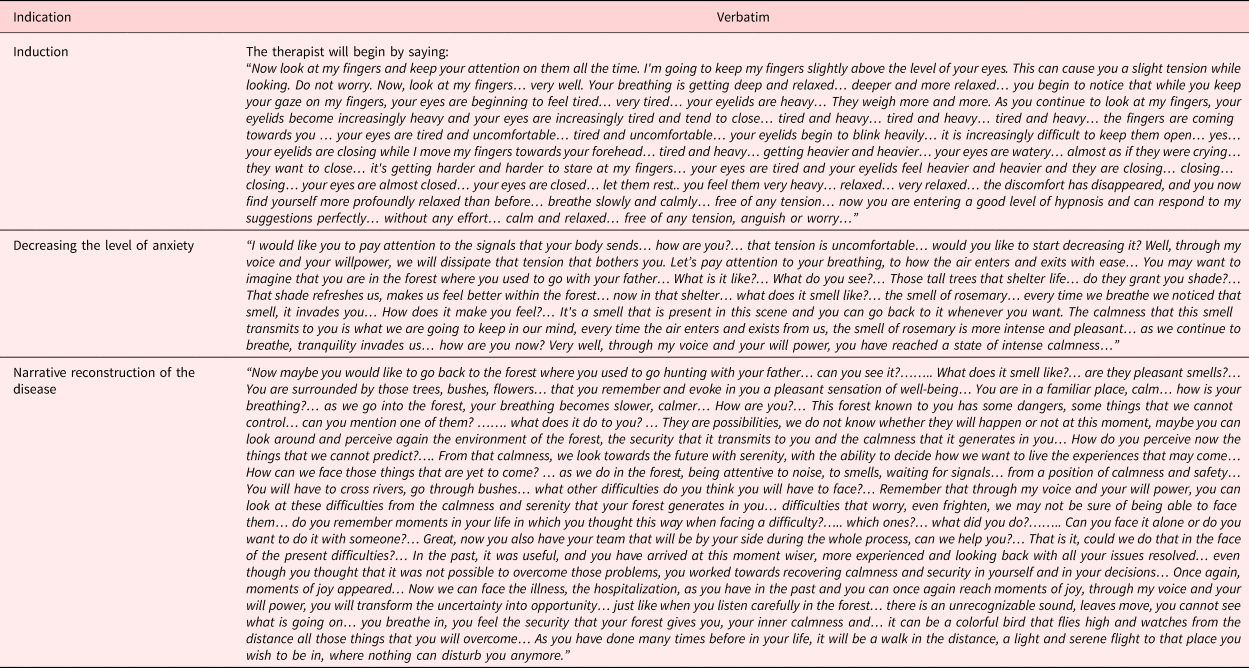

Ten sessions of clinical hypnosis were completed. In the first one, the procedure of clinical hypnosis was explained, showing what it consisted of, and correcting erroneous conceptions, also motivating and making the patient responsible for his treatment and confirming the objectives to be achieved. The following nine sessions with hypnosis were carried out following the standardized hypnotic protocol according to González-Ordi (Reference González-Ordi2013), composed of the following phases: pre-inductive, application of hypnotic induction techniques, administration of specific suggestions, and post-hypnotic phase. For the induction phase, the ocular fixation technique (Braid method) was used (González-Ordi, Reference González-Ordi2013). The exact language used can be seen in Table 2.

Table 2. Exact wording used in the intervention with clinical hypnosis

In the first two sessions of hypnosis, the mountain descent technique (González-Ordi, Reference González-Ordi2013) was used as a stabilization and reinforcement strategy. In the following seven sessions, a shorter stabilization with a countdown from 10 to 0 was used, given the high involvement of the patient.

The specific suggestions used, according to the proposed objectives, are detailed below:

a) Decrease and manage the level of physiological activation.

Suggestions aimed at relaxation and well-being were used, beginning with the suggestion of being in a forest in which sounds and smells transported FM to moments of extreme calmness (Table 2).

b) Search for useful confrontation strategies geared toward the death process and the associated fears.

The focus was on the strategies to treat the symptoms, the difficulties presented, and the proximity of death, using hypnotic suggestions: “being in a forest full of possible dangers” where FM proposed the strategies he would use in these situations, which would then be carried to the present in his struggle against the dangers of his illness and the process of death. From this suggestion, he used as coping tools: prudence in the face of decisions that implied his health or well-being, calmness to help with the waiting, and the need to request help to overcome the most complicated moments. Positive expectations were promoted toward the change and recovery of these tools. This improved the perception of control over his situation and communication with his healthcare team. The literal text of the “metaphor of the forest” can be seen in Table 2.

c) Trauma management for the CVC and PICC placement attempts.

Three sessions were dedicated to the gradual exposure to the stressful situations experienced, diminishing with the tools previously learned the emotional intensity of both events. A narrative reconstruction of the lived events related to the previous needle insertions was carried out and suggestions of emotional control were given.

d) Training for the placement of the MC puncture.

First, psychoeducation on the MC placement was carried out and FM's doubts regarding the protocol and the differences with the previous attempts were resolved.

A clinical hypnosis session of exposure to the MC placement was held to which the specific suggestions of emotional control, decrease of activation, and success of the test were associated through FM's explicit collaboration. A suggestion previously agreed upon: “the arm is like a knife block, easy to penetrate and always leaves the knives correctly placed” was applied to help him.

e) Session for the MC placement, jointly with the nursing team.

It began with relaxation suggestions and the administration of 5mg of midazolam subcutaneously 15 minutes before starting the procedure. During the ultrasound, the suggestion of the rubber knife block was initiated (adaptable and easy to penetrate).

Suggestions of pressure and relief were applied, associated with the success of the technique. Two punctures were needed for the MC placement. The procedure lasted approximately 40 minutes from the start of the hypnotic induction until the moment the medical staff left the room. At all times, FM was calm and cooperative, and at the end of the implementation, he expressed his satisfaction.

Results

The placement of the MC was possible despite the difficulties expressed during the evaluation. The MC did not need to be repositioned or caused any complication, thus remaining in place until the death of the patient, 16 days later. This new route of drug administration, intravenous drug adjustment and emotion management allowed FM to maintain physical symptoms at acceptable levels during the week prior to his death. Pain, anxiety, insomnia, and fear were controlled symptoms one week before his death. Dyspnea remained a difficult symptom to control. Nevertheless, it did not transform into a refractory symptom that required sedation.

Discussion

The placement of a MC does not usually generate emotional impact on the patients to which they are applied (Bortolussi, et al., Reference Bortolussi, Zotti, Conte, Marson, Polesel, Colussi, Piazza, Tabaro and Spazzapan2015). However, there are cases in which previous conditions or psychological difficulties make the procedure impossible. In this study, it has been shown that clinical hypnosis is a simple intervention that is easy to apply, accepted by the patient, which solves the phobic behaviors associated with puncture procedures and improves the patient's general well-being, as shown in the case of FM, who was able to achieve better control of his symptoms and greater comfort at the end of his life.