Inclusive education in the Pacific region, as in the rest of the world, is grounded in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations, 1989), the Salamanca Statement (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 1994), and the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, 2006). United Nations agencies have continued to urge governments to ensure an inclusive education system for children at all levels, and these efforts have led to the Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action (UNESCO, 2015). Nations in the Pacific have responded to this expectation for inclusive education for students who have disabilities (Sharma, Loreman, & Macanawai, Reference Sharma, Loreman and Macanawai2016; Tones et al., Reference Tones, Pillay, Carrington, Chandra, Duke and Joseph2017).

The current study focused on the small Pacific Republic of Nauru, situated in the Micronesian central Pacific Ocean. With 11,347 residents, Nauru is the smallest state in the South Pacific, and the third smallest state by area in the world, with 21 square kilometres. Nauru gained independence from Australian administration in 1968, although it remains reliant on Australian aid. Ongoing support includes commitments such as the Aid Investment Plan (Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade [DFAT], 2015).

Partnership priorities between Australia and Nauru have focused on improving educational learning experiences for Nauruan students (Rose, Pakula, & Barkat, Reference Rose, Pakula and Barkat2018). In 2011, the national census determined that Nauru had a school population of 2,526 students, of whom 42 had disabilities (Republic of Nauru Government Bureau of Statistics, 2015). As well, the census showed that a high percentage, between 15 and 27%, of school-aged children who have disabilities had never attended school (Republic of Nauru Government Bureau of Statistics, 2015). It has been reported that ‘anecdotal evidence suggests that parents of students with a disability are reluctant to enrol students’ (DFAT, 2012, p. 21).

Inclusive education initiatives for Nauru were first articulated as a result of the Pacific Education Development Framework (Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, 2009). The framework provided the vision for quality education in all Pacific countries. Additionally, the framework specifically addressed the needs of students with special educational needs, with a vision of ‘an inclusive, barrier-free, and rights-based society for people with disabilities, which embraces the diversity of all Pacific people’ (Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, 2009, p. 9).

Subsequently, Nauru’s commitment to inclusive education was mandated in the Education Act (Republic of Nauru, 2011a), which stipulated the principles of inclusive education and the provisions for children with special educational needs. The principles of inclusive education meant that school-age children who have a disability must, where practicable, be enrolled in and attend a school, and be allowed to participate in all activities offered by the school. As well, a special education centre was to be available for students who ‘cannot attend a school’ (Republic of Nauru, 2011a, section 95.3). The operationalisation of this part of the Act is the Able-Disable Centre, which had enrolments of 35 preschool and school-aged students between 2011 and 2014. Current attendance statistics are, however, difficult to ascertain because of the variability in children going to school on a day-to-day basis (Republic of Nauru Government Bureau of Statistics, 2015). The emphasis on disability in the Act reflects the current position of inclusive education in Nauru. The locating of disability in legislation is reflected in other Nauru documents such as the Footpath II: Education and Training Strategic Plan 2008–2013 (Republic of Nauru, 2011b), which seeks to improve special education qualifications for teachers in the Able-Disable Centre and address the low enrolment figures of students with disabilities in schools (DFAT, 2012).

To further address the gap in the education legislation regarding inclusive education, the Republic of Nauru Department of Education commissioned a national project to be put into place that sought to not only develop a Nauru policy in inclusive education but also unpack the policy in terms of the professional development that would need to support it. To meet this end, the University of New England Inclusive Education team, together with contracted staff from the University of Newcastle, assisted in the development of a project that sought to address the delivery of inclusive education practices in Nauru. As a result of this initiative, the Nauru Inclusive Education Policy and Guidelines 2017 (Page, Reference Page2018) was ratified by the Republic of Nauru Government on 27 November 2018.

The policy set out the aims and rationale for inclusive education as well as defined the policy directions, guidelines, roles, and responsibilities for teaching staff in Nauru. From this policy, a series of workshops have been conducted that seek to develop the capacity for teachers to become inclusive teachers. The second stage of the project also plans to establish specialist service provision for students requiring additional assistance.

Parent and Teacher Attitudes Towards Inclusive Education

An important component of successful inclusive education involves not only positive parent attitudes but also positive teacher attitudes (e.g., de Boer, Pijl, & Minnaert, Reference de Boer, Pijl and Minnaert2010; Sharma & Sokal, Reference Sharma and Sokal2016; Varcoe & Boyle, Reference Varcoe and Boyle2014). Research on parent and teacher attitudes to inclusive education for children with disabilities has been carried out around the world, but not yet in Nauru. The differences in contexts are significant, but previous research can inform this study.

Parents of children with disabilities have often been the driving forces for inclusion for their children in local education. In a review of the literature regarding parental attitudes towards inclusive education, de Boer et al. (Reference de Boer, Pijl and Minnaert2010) reported that positive attitudes from parents of children with disabilities were not necessarily present, while parents of typically developing children were more positive, seeing benefits for their children in being educated in a diverse school. Parents can see benefits as well as hold concerns about their children being included in education (Page, Boyle, McKay, & Mavropoulou, Reference Page, Boyle, McKay and Mavropoulou2019). Both parents who have a child with a disability and those without are more positive when they have had more experience with children with special educational needs (de Boer & Munde, Reference de Boer and Munde2015). Moreover, the severity of disability impacts on parental perceptions of inclusion. Parents with children with mild disabilities are more positive than parents with children with moderate or severe impairments (Leyser & Kirk, Reference Leyser and Kirk2004).

The interrelationship between these variables (Keith, Bennetto, & Rogge, Reference Keith, Bennetto and Rogge2015) has implications for the relevance of education to improve levels of positive perception towards inclusion. Specifically, parent perceptions of social norms and their knowledge of policy and provisions can predict their attitudes (Lui, Sin, Yang, Forlin, & Ho, Reference Lui, Sin, Yang, Forlin and Ho2015), and therefore valuing children with disabilities and providing information about policies and provisions will help build positive attitudes for parents (Jigyel, Miller, Mavropoulou, & Berman, Reference Jigyel, Miller, Mavropoulou and Berman2018).

How society perceives disability has an impact on the attitudes of parents and teachers, and this is distinctive in different cultures. Werner and Shulman (Reference Werner and Shulman2015) investigated the stigma among family carers of individuals with developmental disabilities, comparing caregivers of individuals with intellectual disabilities, autism spectrum disorder, and physical disabilities. The authors reported that there was a greater stigma among caregivers of individuals with autism and that this was related to feeling embarrassed by the child’s behaviour. The child’s behaviour had a negative impact on the parent, which led to the parent reducing the amount of time that they went into the community with the child, reducing contact with friends and relatives, and not telling others that the child has autism. Stigma can also be culturally defined. Findings from research by Lui et al. (Reference Lui, Sin, Yang, Forlin and Ho2015) indicated that parental values that belong to cultures where there is an emphasis on collective social group obligations, such as is the case in many Pacific countries (Meissel & Rubie-Davies, Reference Meissel and Rubie-Davies2016), are strongly influenced by groups including teachers, principals, and the community. The shame associated with a disability creates a barrier for families (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Loreman and Macanawai2016). Additionally, parental attitudes are also affected by knowledge about inclusive education policy in that positive attitudes are correlated with an in-depth understanding of the legislation and practices associated with inclusive education (Lui et al., Reference Lui, Sin, Yang, Forlin and Ho2015).

It is not enough to consider the attitudes of parents of children with disabilities. As well, attitudes of other parents are important, as they can influence the level of acceptance of students with disabilities into local schools (de Boer & Munde, Reference de Boer and Munde2015; Lui et al., Reference Lui, Sin, Yang, Forlin and Ho2015). While including all students in the one setting poses potential risks for students with and without disability (Hartley, Bauman, Nixon, & Davis, Reference Hartley, Bauman, Nixon and Davis2015), it is recognised that typically developing children are likely to benefit from inclusive education (Florian, Black-Hawkins, & Rouse, Reference Florian, Black-Hawkins and Rouse2016).

Stanley, Grimbeek, Bryer, and Beamish (Reference Stanley, Grimbeek, Bryer, Beamish, Bartlett, Bryer and Roebuck2003) found that teachers and parents have differing views about inclusion. Using a teacher and parent attitude survey, the findings indicated that teachers were less positive than parents in the acceptance and treatment of children with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual impairment in regular classrooms, highlighting potential incongruence in parent and teacher attitudes. Attitudes of teachers, as a group by themselves, are reported to reveal similar trends to attitudes of parents in that they are affected by the level of severity and type of disability (Al-Zyoudi, Reference Al-Zyoudi2006) as well as by prior personal experience with people with disabilities (Shalev, Asmus, Carter, & Moss, Reference Shalev, Asmus, Carter and Moss2016). Additionally, teachers who display a positive attitude, as for parents, are more likely to have a positive influence on other children in regard to students with special needs (Hoskin, Boyle, & Anderson, Reference Hoskin, Boyle and Anderson2015; Subban & Sharma, Reference Subban and Sharma2005).

A key component of teacher attitudes to inclusion is the self-efficacy that underpins expertise in inclusive teaching. Self-efficacy, or teacher beliefs in their ability to succeed, is related to levels of positive attitudes towards inclusion (Forlin, Sharma, & Loreman, Reference Forlin, Sharma and Loreman2014), which in turn promotes the delivery of effective inclusive education practice. There is a relationship between highly inclusive teachers and their self-efficacy, where good inclusive practices lend themselves to lower degrees of concern and positive attitudes towards inclusion (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Loreman and Macanawai2016; Sharma & Sokal, Reference Sharma and Sokal2016).

Attitudes to inclusive education from parents and teachers that were generally positive have been shown to be unstable over time and, as previously demonstrated, are influenced by an understanding of the nature of the disability as well as by experience with people with disabilities (Schwab, Reference Schwab2018). Because of the malleability of attitudes, teacher education has been the focus as teacher education institutions can play an important role in developing appropriate attitudes to inclusion (Varcoe & Boyle, Reference Varcoe and Boyle2014). When teachers are explicitly taught about special and inclusive education, they are more likely to have a positive attitude in their willingness and ability to implement inclusive approaches and ultimately impact on the intention to teach in inclusive classrooms (Sharma, Simi, & Forlin, Reference Sharma, Simi and Forlin2015). Experience working with students with special educational needs also was found to significantly increase the perception of self-efficacy in teachers (Loreman, Earle, Sharma, & Forlin, Reference Loreman, Earle, Sharma and Forlin2007). To complicate matters, findings from Boyle, Topping, and Jindal-Snape (Reference Boyle, Topping and Jindal-Snape2013) indicate that the more experienced a teacher is, the less likely they are to have a positive attitude towards inclusion. The authors suggested that this may be the result of a lack of resources and poor peer support, and it is perhaps related to the nature of their initial teacher education, which may not have included any special or inclusive education content.

The Study

In recognition of parent and teacher attitudes as a key aspect of successful inclusive education, we aimed to explore these in Nauru as inclusive education is emerging. In this study, we aimed to investigate the attitudes of parents towards inclusion as well as teacher attitudes towards inclusion that included teacher perceptions of their competency to deliver inclusive education.

All teachers in Nauru schools who identified themselves as Nauru nationals and all parents with students attending school were invited to participate in the survey by their school principal through the Department of Education. Written permission and consent were obtained from each participant. Approval for the research was provided by the Department of Education in Nauru and the University of New England’s Human Research Ethics Committee.

Participants

From those invited to participate, 20 parents (13 female, seven male) completed and returned the parent survey. Six of these parents reported having a child with a disability, and 11 stated that they have contact with a child with a disability.

From a teaching staff of 70 Nauruan nationals, 20 teachers (19 female, one male) completed the teacher survey. Of these, nine reported having contact with students with disability. The teachers ranged in experience in teaching from 1 to 20 years. Of the 11 schools in Nauru, teachers were from one secondary, six primary, and two special schools. Three teachers taught in secondary school and 15 were from the primary sector.

Instruments

Two survey tools were used: the Parent Attitudes to Inclusion Scale (PATI; Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy, & Widaman, Reference Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy and Widaman1998) and the Teacher Attitudes Towards Inclusion Scale – Revised (TAIS-R; Boyle & Costello, Reference Boyle and Costello2016).

The surveys were printed and sent home to parents from their children’s schools. Teachers accessed the TAIS-R in print that was made available at their school.

Both surveys have a 6-point Likert scale with answers ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 6 (strongly disagree). To respond to the context of Nauru, and as the surveys were developed elsewhere, its relevance in Nauru was checked in consultation with local education professionals. No amendments to the test items were made as a result of the collaborative consultation process with senior members of the Department of Education and the Ministry of Education.

The PATI is an 11-item scale that explores perceptions of inclusion (Palmer, Fuller, Arora, & Nelson, Reference Palmer, Fuller, Arora and Nelson2001) and reflects the ‘multidimensional nature of parent perceptions regarding inclusive practices for children with significant cognitive disabilities’ (Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy, Widaman, & Best, Reference Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy, Widaman and Best1998, p. 273). The PATI items combine to reflect three factors. These three factors, as described by Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy, and Widaman (Reference Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy and Widaman1998), are provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Factors in the Parent Attitudes to Inclusion Scale (PATI; Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy, & Widaman, Reference Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy and Widaman1998)

The TAIS-R is a 20-item survey and provides psychometrically validated measures for two sections: Part A has 11 items that ask teachers about global attitude towards inclusion, measuring items such as attitudes towards having children with special needs in mainstream classrooms, grouping children according to their needs, and the perceived impact to the learning environment. A further nine questions (Part B) about training and perceived competency measure attitudes towards professional training, ongoing professional development, and personal feelings of competency towards inclusive education.

Although the PATI has a comparable Teacher Attitudes to Inclusion (TATI) scale (Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Grimbeek, Bryer, Beamish, Bartlett, Bryer and Roebuck2003), the TAIS-R was used instead, as the purpose of data collection was to ascertain perceptions of levels of the training and perceived competency, and this was a strength of the selected tool.

Both instruments have internal consistency overall and in each factor within them. Each factor in the PATI realised Cronbach’s alpha reliabilities of .80, .82, and .66 (Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy, & Widaman, Reference Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy and Widaman1998). The TAIS-R has a Cronbach’s alpha of .85 with a European population. It builds upon the Teacher Attitude Towards Inclusion Scale (TAIS) by Boyle et al. (Reference Boyle, Topping and Jindal-Snape2013) in terms of providing better reliability of the constructs. The scales were calculated to be reliable, with Cronbach’s alphas of .848 and .828 (Boyle & Costello, Reference Boyle and Costello2016).

Findings

Parents’ Attitudes

To support this analysis, the item mean scores were calculated, and the items were then placed in rank order with the strongest positive attitudes first (see Table 2). In reporting this research, the item language has been changed to reflect the intention of the item after reverse scoring. For example, Item 1 asks ‘including children with special needs in my classroom can adversely affect the learning environment’. A high score indicates strongly disagree and is reversed scored. When reverse scored, the item indicates a positive attitude towards inclusion: that children do not adversely affect the learning environment.

Table 2. Parent Attitudes to Inclusion Scale (PATI) Items Ranked According to Strength of Attitudes

Note. Items 2, 3, 5, 6, and 9 are reworded to reflect the reverse scoring.

Parents’ Attitudes Ranked Items

Tally scores were calculated for each item, to indicate the number of respondents who rated the item at each level of agreement. This analysis showed a full range of responses for every item, which is in contrast to the American norming of the tool where some strongly agree or disagree responses were considered abnormal (Bryer, Grimbeek, Beamish, & Stanley, Reference Bryer, Grimbeek, Beamish and Stanley2004).

What this range tells us is that there are trends of attitudes, but that there is not a consensus of attitudes of these parents as a group at this time. The strongest items do suggest that the parents do not think that their children will be mistreated by peers, that it is possible to cater for their children in the classroom, and that inclusive education can work. However, for all items some parents strongly disagreed.

Parent Attitudes Comparing Subsection Scores

Figure 1 shows the mean scores across the three dimensions of the PATI and shows that in the current study parents were more supportive of inclusion when it related directly to the educational benefits for their children rather than in relation to more general benefits. Specifically, parents reported a higher level of support for the dimension that involved child acceptance and treatment (CAT; M = 3.75, SD = 11) where higher scores indicated a relative lack of concern that a child would be mistreated or isolated as a result of increased inclusion. The second highest dimension was quality of educational services (QES; M = 3.54, SD = 1), which is concerned with the child’s opportunities to receive a more focused curriculum and more individualised care. The positive but slightly lower mean result indicated that parents believed the quality of their child’s education would be maintained in a general education setting. The third dimension covered items that referred to mutual benefits of inclusion (MBI; M = 3.16, SD = 1). The lower scores in this domain suggested that parents were more likely to focus on the individual benefits of inclusive placement.

Figure 1. Mean Scores Across the Dimensions of the Parent Attitudes to Inclusion Scale (PATI; Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy, & Widaman, Reference Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy and Widaman1998): Child Acceptance and Treatment (CAT), Quality of Educational Services (QES) and Mutual Benefits of Inclusion (MBI).

The means of all three PATI scale factors were compared using paired-samples t-test procedures for the three comparisons. None of the mean scores for the scales between the CAT, QES, and MBI produced any significant differences, where CAT (M = 3.75, SD = 11) and QES (M = 3.54, SD = 1), t(1) = –.93, p = .523; CAT (M = 3.75, SD = 11) and MBI (M = 3.16, SD = 1), t(1) = 1.50, p = .374; and QES (M = 3.54, SD = 1) and MBI (M = 3.16, SD = 1), t(3) = 2.45, p = .092.

Teacher Attitudes

Unlike the PATI, the TAIS-R and the amended version for preservice teachers, Boyle’s (Reference Boyle2014) Teacher Attitudes Towards Inclusion Scale – Amended (TAIS-A), is typically reported in terms of a total inclusion score (Boyle et al., Reference Boyle, Topping and Jindal-Snape2013; Varcoe & Boyle, Reference Varcoe and Boyle2014). Thus, the higher the total score, the more positive teacher attitudes are towards inclusion (Boyle & Costello, Reference Boyle and Costello2016).

The total mean for the TATI is M = 3.72 (SD = 0.53). Within that, the mean score for the teacher responses for the TATI subdomains Part A (M = 3.65, SD = 0.53) and Part B (M = 3.81, SD = 0.55) are above 3.5 and indicate more positive attitudes than negative attitudes in both global attitudes as well as issues relating to training and perceived teacher competency.

Teacher Attitudes Ranked Items

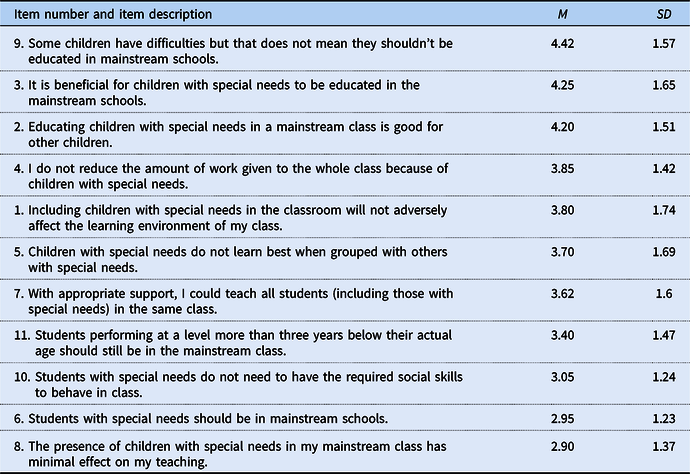

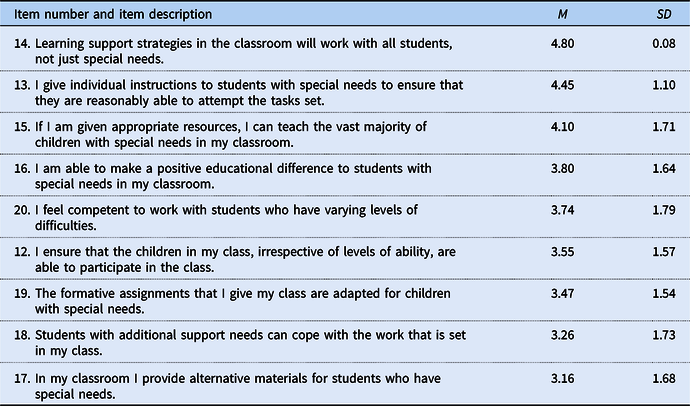

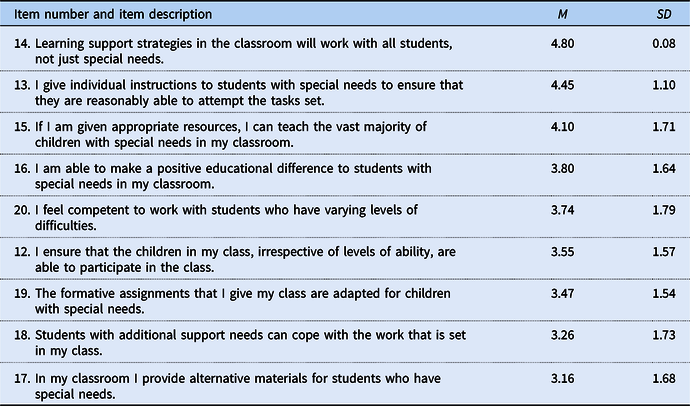

The responses of the teachers to the TATI items are collated in Tables 3 and 4, with the mean scores of teachers’ global attitudes towards inclusion in Table 3 and the mean scores of items related to training and perceived competency in Table 4.

Table 3. Teacher Attitudes Towards Inclusion Scale – Revised (TAIS-R Part A: Global Attitude Towards Inclusion) Items Ranked According to Strength of Attitudes

Table 4. Teacher Attitudes Towards Inclusion Scale – Revised (TAIS-R Part B: Training and Perceived Competency) Items Ranked According to Strength of Attitudes

The items related to a global attitude towards inclusion used various terms that may influence their rankings. For example, the highest item talks about ‘difficulties’ but most others refer to ‘special needs’. This could be a reason for Item 9 being at the top and the similar Item 6 being near the bottom.

In this group of items, there were evident trends across the teachers that reflect the mean ranking. The top three items were stronger across the group; however, there were still five teachers who disagreed with Item 9 and seven who disagreed with Item 3, showing a diversity of opinion about inclusion. The responses for Item 4 were concentrated in the centre (agree and disagree), with fewer teachers having stronger views either way. The responses for Items 1, 5, and 7 were relatively evenly spread across the full range of the scale, the mean reflecting the full range of attitudes to these items.

Item 11 elicited a central focus, again with 12 teachers either agreeing or disagreeing and four at each end of the scales (somewhat and strongly agreeing or disagreeing). Social skills were the focus of Item 10, which produced a 13:7 ratio of teachers agreeing and disagreeing, and the final item had 14 teachers indicating that the presence of a student with special needs had a more-than-minimal effect on their teaching.

Table 4 shows the mean scores for the items relating to training and perceived competency. Results indicate n = 3 items above a mean of 4, again indicating teachers’ beliefs of possessing the necessary competencies to provide inclusive education services.

In these items, teachers focused on the general idea of learning support strategies as well as strategies such as giving instructions, formative assessment, and alternative materials. The more general Item 14 was ranked more highly, indicating that when asked about specific strategies there was less sense of self-efficacy. The spread of responses was considerable for these items. Items 14 and 13 showed the most positive attitudes, with no-one responding with somewhat or strongly disagree for Item 14, and only one participant somewhat disagreeing for Item 13. Item 13 asked about instructions given to individual students and showed that 16 teachers do this, while four do not. Responses to Item 17 revealed that half of the teachers do not provide alternative materials for students when needed.

Otherwise, a full range of responses were provided for the rest of the items in Part B. There were some trends evident for other items: Item 15 generated 14 positive responses and six negative, and Item 16 had 12 positive responses and eight negative responses. Item 12 was equally balanced, with approximately half the teachers indicating they ensured all students can participate in class. In Item 18, eight teachers felt that the student with additional needs in their class can cope with the work.

Most items were responded to across the full scale, showing that there was a considerable lack of consensus on most issues. Although the means indicate the relative strength of attitudes from the group of participants, this does not indicate trends across the group in many instances. Instead, there is a wide range of attitudes concerning the aspects of inclusion that are described in these items.

Teachers’ Attitudes Comparing Subsection Scores

A paired-sample t-test on the two variables indicated no difference between Part A: Global Attitude Towards Inclusion and Part B: Training and Perceived Competency. The teachers’ scores for attitudes towards inclusive education (M = 3.94, SD = 0.34) were similar in the mean scores for training and perceived competency (M = 3.81, SD = 0.55), t(8) = 1.44, p = .189.

Discussion

In the current study, we aimed to explore the attitudes of Nauruan parents and teachers regarding inclusive education. Because of the small sample, the findings give us preliminary insights into the nature of parent and teacher attitudes in Nauru at this time and suggest that there is a range of attitudes that combined are relatively positive; however, closer analysis reveals little consensus about inclusive education as an ideal, or about current teacher expertise to enact inclusive education.

The limitations of the study include the application of an instrument that has been designed and tested for Western populations. Although English-language items were checked by the Nauru Department of Education and Ministry of Education for understanding, the items did reflect what constitutes the dominant framework around inclusive education thinking in English-speaking countries. While a process of consultation with senior members of the Department of Education and Ministry of Education in Nauru did result in the decision to use the survey in its original format, the survey results allow a starting point only of the understanding of inclusive education. Future research can be improved by using more appropriate methods and tools. The current research, therefore, serves to highlight areas to improve research methodology in the future that involves the personal perspectives of Pacific educational and social issues (Vaioleti, Reference Vaioleti2006).

In terms of the current study, however, while higher item scores using these instruments indicate more positive levels of attitude towards inclusion (Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy, & Widaman, Reference Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy and Widaman1998) and can be compared with previous research using the same instruments, this is not very revealing about the nature of the attitudes. Instead, it is the items themselves and/or the dimensions that have been used in comparison rather than overall totals (Bryer et al., Reference Bryer, Grimbeek, Beamish and Stanley2004; Palmer et al., Reference Palmer, Fuller, Arora and Nelson2001; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Grimbeek, Bryer, Beamish, Bartlett, Bryer and Roebuck2003). Analysis of the items in this study has suggested that there may be significant issues around the terminology being used that need to be investigated further. For example, the item about ‘appropriate resources’ in Part B (Item 15) and ‘appropriate support’ in Part A (Item 7) provided discrepant results. Although 14 teachers indicated that they could teach the majority of children with ‘appropriate resources’, only 10 replied that they could do this with ‘appropriate support’. These items raise the question of what the participants understood by these two terms: what appropriate resources and support might mean to them. As well, terms like ‘special needs’ and ‘difficulties’ have embedded meanings in different contexts, and it is not clear how these were interpreted in this situation.

This survey was carried out at a time when inclusive education was being introduced through international projects, and this has been happening in neighbouring Pacific nations at the same time. Since this survey, there has been the development of policy and implementation of teacher professional learning with a focus on inclusive education. As well, support in educational casework for children with disabilities has been occurring. Because of these interventions, it is assumed that the shared language of inclusive education is becoming more established and that future surveys of parents and teachers will reflect a better understanding of terminology and ideas of inclusive education. A further limitation is that only 20 parents and 20 teachers responded to the survey. Although a disappointing return rate from the distribution, the surveys have provided valuable information that can be built upon in the future.

The PATI has been used in Australia and the United States to investigate parent attitudes to inclusion. The results from the current study support other dimensional data generated using the PATI in Australian samples, where parents also indicated lower scores on the items relating to MBI (particularly items 8 and 11), although the differences in this study are not statistically significant. The Australian sample also scored lower in terms of positive attitudes about the MBI than an American sample it was compared against (Bryer et al., Reference Bryer, Grimbeek, Beamish and Stanley2004). Both the Australian and American samples indicated strong positive attitudes towards items 5, 6, 9, and 10, relating to the dimensions of QES and CAT, which was not an outcome in this study, however. That parents report lower scores in the MBI is contrary to earlier research that investigated the attitudes of parents of students with severe disabilities (Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy, & Widaman, Reference Palmer, Borthwick-Duffy and Widaman1998), which showed more positive attitudes regarding the impact of inclusion on mutual social benefits and the acceptance and treatment of their child. In comparison to this earlier study, parents were more apprehensive regarding the impact of inclusion on the QES their child receives. The authors indicate that the level of the students’ severe impairment paired with behavioural issues are contributing factors to the findings of this research.

The TAIS-A, a similar assessment of preservice preschool and primary teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion, also provided Part B: Training and Perceived Competency, although some of the items were different, makes comparisons inappropriate (Varcoe & Boyle, Reference Varcoe and Boyle2014). Studies in Australia of preservice teachers reveal a mildly positive mean affect over negative affect. A study by Varcoe and Boyle (Reference Varcoe and Boyle2014) also found a significant relationship between participants who had a higher training and perceived competency score and a higher global inclusion score. Similar positive reports (mildly positive mean results) were found in another study in Australia using the TAIS-A (Kraska & Boyle, Reference Kraska and Boyle2014). In line with these results, Lambe and Bones (Reference Lambe and Bones2006) state that while preservice teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion are generally positive, they express a marked concern about training and competence. This study, however, did not show a difference between attitude and training.

General attitudes towards inclusion have been found to be a significant predictor of successful inclusive education, where teachers who reported successful classroom inclusion hold positive attitudes towards inclusion (Avramidis, Bayliss, & Burden, Reference Avramidis, Bayliss and Burden2000). Parents also report positive attitudes that can be built upon. However, attitudes are linked to specific situations and it would be useful to explore further the benefits and concerns that these families had that underpinned their attitudes as measured in this brief way. Understanding perceived benefits and challenges associated with inclusive education (Jigyel et al., Reference Jigyel, Miller, Mavropoulou and Berman2018; Schwab, Reference Schwab2018) is important to assist in responding to those concerns and in turn supporting changes in attitudes.

Finally, because two different scales were used for parents and teachers, comparisons of the results could not be made, although comparable scales (to include a subscale of training and competency) are not available. Further research could delve more deeply through semistructured interviews and a Nauruan-speaking interviewer who could explore the ideas much more in depth. As Sharma et al. (Reference Sharma, Loreman and Macanawai2016) point out, local approaches to research that contribute to local understanding is central to the successful implementation of inclusive education.

Conclusion and Implications

This research has provided preliminary information regarding parent and teacher attitudes in Nauru at a time of emerging inclusive education. Because of the limited scope of the study, it is not possible to draw conclusions from the results, and this paper serves to present initial trends only. The lack of consensus in these results will need to be addressed to move forward in the provision of inclusive education in Nauru. The findings provide a platform from which to develop further conversations around the role that parents and teachers play in education for students who have disabilities. The context of inclusive education in Nauru is consistent with other developing nations in the Pacific, who face the challenges of resourcing, specialised teacher education, recent changes in legislation, and varied community perspectives (Tavoli & Whippy, Reference Tavoli and Whippy2010). Action is contributing to an increase in resourcing, to building teacher expertise in inclusive and special education, and establishing policy to guide practice that ensures the Nauruan education system responds to the international expectations of universal and inclusive education.

The findings presented can inform ongoing decisions regarding the development of inclusive practices and also in terms of teacher education programs. A specific teacher education course in inclusive education has been recognised to be effective in improving attitudes towards inclusion practices (Boyle et al., Reference Boyle, Topping and Jindal-Snape2013). Additionally, in-service professional development (Sokal & Sharma, Reference Sokal and Sharma2014) and community education courses have been shown to positively affect attitudes towards disabilities and can be implemented at a local level (Miles, Lene, & Merumeru, Reference Miles, Lene and Merumeru2014).

Policies should never be static but move forward and improve with changing circumstances, knowledge, and understanding of the community that they serve. Community education is a further consideration and an important next step that will help develop a foundation of shared understanding of the possibilities of inclusive education. A focus will be to provide a platform from which to address the parental attitude dimension of MBI, which was a relatively lower domain score than the domain scores for CAT and QES. Policies also need to build on the strengths of the reported data that will help to develop an educational environment that supports all the children of the nation. The Nauru Inclusive Education Policy and Guidelines 2017 is important as a key resource to drive the commitment and guidance of inclusive education and safeguard the ongoing development of inclusive practices (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Simi and Forlin2015).

Since attitudes are malleable and are dependent on experience, there are possibilities for the current interventions in inclusive education to make a difference to parent and teacher attitudes and in turn to better support the establishment of inclusive education in Nauru.