Introduction

The exotic creatures that first reached Europe during the sixteenth century had profound effects on Occidental notions of the world and its inhabitants, as well as providing economic opportunities in the lucrative marketplaces of trade and accumulation. Many historians have explored how new animals and plants acted as a challenge to traditional European ways of seeing the world.Footnote 1 Much historical attention has consequently been devoted to Europeans’ interactions in colonial settings and the impact on the collectors of imported exotics, but there has been less focus on how novel colonial objects were assimilated and altered once they reached, and circulated around, Europe. In particular, exotic animals have received far less attention than plants, despite the rich tradition of faunal symbolism that persisted through the early modern period. What these items of translocated naturalia became and how they were understood in Europe cannot be taken as self-evident: there were undoubtedly significant exchanges between these things and the people who encountered them. The story did not end once crates of body parts reached the docks of Cadiz, Antwerp or Amsterdam.Footnote 2

The dominant model of understanding of the history of exotica within Europe is one of categorisation. Historians of natural history tend to assume the desirability of neat taxonomies to which ambigous objects could be challenging. In fact, quite the opposite could be true: liminal and mutable objects were valuable mediators in European natural history, co-opted for multiple uses. They were puzzles of assemblage and taxonomic placement, but certainly not crisis-inducing problems. This will be demonstrated using a creature of ambiguous provenance, the Old World pangolin, and its natural historical entanglement with its New World counterpart, the armadillo. European scholars and traders were certainly not the only figures with significant agency in the early modern global networks around which exotic creatures moved.Footnote 3 Animals were physically altered and valued in different ways by the people who hunted, traded and collected them. Transportation often necessitated the dismantling of whole animals, because of the obstacles and costs involved. Housing specimens in transit and preserving them from decay was very difficult, so the commercially valuable or easily preserved parts of creatures were more likely to be extracted and transported.Footnote 4 Natural objects were enigmatic things, serving different symbolic functions amongst the different groups of people handling them.Footnote 5 These different functions were never entirely confined to their locales, as different kinds of symbolism and knowledge surrounding such objects were often transported with them.

Animals and plants that were new for Europeans underwent complex processes of assimilation in scholarship and curiosity cabinets, as naturalists assembled creatures’ identities from the often-ambiguous physical animal parts and pieces of information accompanying them. Early modern naturalists were not engaged only in the collection of preformed material but also in active construction. This involved the gathering and manipulation of objects and information to create entities that fulfilled specific symbolic roles. The immutability and mobility of an exotic object traded from the Indies was therefore never a simple attribute but rather a matter of transport and trade: sometimes it was important for naturalists to emphasize identity with the supposedly original material as it existed in the Orient or Occident, sometimes it was important to completely transform what arrived in Europe.Footnote 6

Often an object’s identity was bound up with a view of an imagined origin that was not the object’s actual physical source, and could undergo dramatic changes as the symbolic construction of the creature shifted over time.Footnote 7 Benjamin Schmidt, for example, has shown how stereotyped exotic icons were transformed, in form and provenance, as they moved across media in “iconic circuits.” These processes shaped the identity of naturalists as much as of the exotic objects and creatures they collected and depicted.Footnote 8 While the commercial enterprises of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and West India Company (WIC) facilitated the flowering of sciences in the Dutch Republic, a naturalist’s ability to market exotic natural history in a commercial economy affected his or her position in scholarly networks.Footnote 9 Examining the publishing industry in the early modern Dutch Republic, Schmidt depicts the use of typified exotica as commodities. In contrast, Dániel Margócsy’s study suggests that commercial processes stimulated differentiation in ways of representing natural objects.Footnote 10 This article will draw more on Margócsy’s argument to explore exotic objects as the diverse results of numerous commodification processes. Focusing on close comparative analysis of natural history accounts, as used in recent history of zoology studies such as those by Paul Smith and Karl Enenkel, it will uncover the work of source collection and networking involved in the production of diverse assembled creatures.Footnote 11

In early modern Europe, a creature’s perceived geographical associations were very significant in its natural history. Though the term ‘biogeography’ was developed in the nineteenth century, it usefully describes ideas surrounding floral and faunal distributions, and, crucially, their accessibility. Such ideas have always been integral to the ways in which plants and animals have been perceived, whether through basic dichotomies of being domestic or alien, or within more complex constructions of geographical and political symbolism. This was especially true in a period during which the known world and its widely distributed contents expanded rapidly, and Janet Browne has demonstrated the importance of biogeographical ideas from the mid-seventeenth century. Early modern scholarship discussed not only “what” things were and “where” they could be found, but also “why” they were found there, though the types of answers sought for have changed dramatically since the seventeenth century.Footnote 12

The routes by which natural objects passed, the forms in which they were transported and their various economic values affected how they were eventually understood. The ancient distinctions between Orient and Occident, neither static nor necessarily geographically defined regions, were given a range of new senses in this period.Footnote 13 The early modern category of the “Indies” was “one of the most highly defined geographic entities” in natural history, with a distinct genre of natural history publications.Footnote 14 Two cases that clearly illustrate these complex processes of natural historical and geographical construction are the pangolin or scaly anteater of Africa and Asia, and the armadillo of the Americas. Armadillos first arrived in Europe in the early sixteenth century, and pangolins in the latter part of the century.

Both travellers abroad and naturalists in Europe first encountered these animals primarily as preserved specimens. The armadillo was especially common in curiosity collections and the rarer pangolin was certainly present in collections such as those of Ulysse Aldrovandi in Bologna, Manfredo Settala in Milan and the Royal Society in London. In fact, along with sawfish rostrums, narwhal teeth, and bird of paradise skins, pangolins and armadillos were part of the requisite set of “standard wonders” making up cabinets of status. A 1554 account by the Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner (1516–1565) described how the armadillo was “easily transported from distant regions, because nature has armed it with a hard skin.” This meant that the “flesh inside can be easily taken out without any harm to the original shape.”Footnote 15 Pangolin carapaces would also have been relatively easy to transport as skins and carapaces with their flesh removed from various regions in Africa and Asia. Once stashed in cabinets, they were also more durable than many other specimens. At least one early modern pangolin specimen, owned by the wealthy Amsterdam apothecary Albertus Seba (1665–1736), still exists in the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography in St. Petersburg. They were also transported as wet specimens- Seba reported receiving one from Ceylon “preserved in Arak.”Footnote 16

It should be emphasised that the pangolin and armadillo initially had very different identities in European natural histories: pangolins were understood as East Indian, armadillos as West Indian. But through the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, their biogeographies and symbolic associations were progressively enmeshed. “Pangolins” travelled west, and “armadillos” frequented the Orient. This change was in part a result of the practical confusion between two strange armoured creatures along shared trade routes, but it was also due to shifting perceptions of the ‘Indies’ in Europe, and their presentation in publications. The processes involved in the generation of such mutable and malleable images of these creatures were also evident in the natural histories of other exotics, and were derived from the way in which more familiar animals had traditionally been understood. Animals had long been constructed as emblematic entities in European scholarship. Though striking examples of particularly hybrid creatures, the histories of the pangolin and armadillo offer insights into the underpinnings of early modern natural history in general.

Historians such as Harold Cook have recently explored the relationship between the European sciences and companies such as the VOC and WIC. These companies funded and implemented the transport networks that brought a wealth of material to Europe, as well as posting physicians and naturalists in distant colonies. As a result, these enterprises deeply affected how science was practiced at an epistemological level.Footnote 17 This study offers a contrasting view to the conclusions drawn by Cook, suggesting that the interconnections between early modern science and commerce did not entail that the emblematic outlook was excised from the production and valuation of knowledge in early modern Europe. Unusual animals from novel places, like the armadillo and pangolin, were not immutable and incongruous entities that caused systemic havoc in natural history. Nor were they biological realities uncovered by the empiricism of a trade-led science. Rather, their novelty and the enigmatic fragments representing them in Europe allowed these animals to be flexibly constructed into diverse commercial packages as Margócsy’s work demonstrates.Footnote 18 Exotic animals were one group of constructed objects through which geographical perceptions, fantasies and anxieties were expressed. They could be malleable materials used to reinforce core European cosmological concepts, particularly the hierarchical Great Chain of Being.Footnote 19

An Indian Lizard

Though ostensibly problematic, ambiguous objects have considerable value as malleable resources for producing, rather than disrupting or threatening, social and cosmological order. An excellent example of this is anthropologist Mary Douglas’s work on the pangolin symbolism of the Lele people in Guinea. For the Lele, the apparently unclassifiable nature of the pangolin allows it to act as a cult focus for men in the tribe who mediate between the human and the supernatural.Footnote 20 The pangolin overcomes “distinctions in the universe,” empowering it to promote fertility through its ritual sacrifice and consumption.Footnote 21 It is tempting to make a comparison with early modern European travel accounts and natural histories recording the interactions with these creatures in European colonies and at home. In such texts, the pangolin was presented as deeply ambiguous, with a liminal lizard-like form. It was a potent symbol, mediating between different kinds of natural forms, cultural boundaries and across geographical distance. The mobile and negotiable character of this mediation is the interest of what follows.

What is now understood as a pangolin was first included in a European natural history work in 1605, the Exoticorum libri decem by the prominent Flemish botanist and physician, Carolus Clusius (1526–1609). Clusius was a professor at Leiden University, but benefitted from material from VOC and WIC trading ships and officials for his work on exotics, never having travelled outside of Europe himself. He described the skin of a Lacertus peregrinus squamosus (foreign scaly lizard) kept by an acquaintance as a “rarity” amongst “his miscellaneous exotica.” Its foot-long body had an extraordinary two and a half foot-long tail, covered with pointed scales, and its feet had long hooked claws.

He mentioned two other similar specimens that he knew of, and one owner had sent him a few scales from a specimen. Though without a scholarly “history,” these objects were not uncommon in cabinets at this time. Yet, strangely, all the skins that Clusius described lacked any provenance.Footnote 22

In Clusius’s account this scaly object was an exotic without an identifying origin beyond being “foreign,” and a “rarity” without being scarce or very valuable. It’s now held that the eight different pangolin species across Asia and Africa differ widely. Clusius mentioned that some of the skins did not look exactly alike, but their scaly nature sufficed for him to class them together. Through the seventeenth century, similarly ambiguous “scaly lizard” specimens circulated around scholarly circles. For example, in 1698, the secretary of the Académie Royale des Sciences in Paris, Jean-Baptiste Du Hamel, reported that he had sent specimens to an anatomist and an author, which they had examined with great interest.Footnote 23

The second major seventeenth-century text dealing with this scaly lizard was published in a 1658 natural history of the East Indies, the Historiae naturalis et medicae Indiae Orientalis, by the Dutch physician Jacobus Bontius (1592–1631), written while working for the VOC in Java in the 1630s. This was published in De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica (1658) compiled by the Dutch naturalist Willem Piso (1611–1678).Footnote 24 The account described a “disemboweled” specimen of a beast from Insulae Tajoán (Island of Taiwan) called De Lacerto Indico, Squamoso (Scaly Indian Lizard), lacking a vernacular name.

This lizard-creature frequented woods and had rigid scales that it raised when aggravated. The author reported that the Dutch called it the “Devil of Taiwan,” perhaps on account of the “horrible form of its skin.”Footnote 25 It tore apart ant nests aggressively with its clawed feet to feed, like the Brazilian Tamandoá (anteater), and was a dish prized by the natives, like those other “great lizards of Brazil,” the Leguánae (iguana) and Tatu (armadillo). This “Devil” is actually absent from Bontius’s manuscripts in the Sherard Collection in Oxford, and is therefore probably a later addition by Piso in Europe from an unknown source.Footnote 26 This manuscript does depict the skin of another creature, described by Bontius as Testudo squamata or “scaled turtle” or “Tamach,” most probably also a pangolin. Though published in Piso’s 1658 work, this hole-digging “somnolent animal” with a “cold nature,” covered in carp-like scales, was not referenced by any later authors describing the “scaly lizard.”Footnote 27

In both Clusius’s Exoticorum and Bontius’s Historiae naturalis, the pangolin is defined by its lizard-like scales, the most tangible characteristic of the carapaces to which these naturalists had access. Clusius’s image and text were often used [for example, fig. 6], though some catalogues depicted new examples. In the posthumous De Quadrupedibus viviparis (1645) of the prolific Bolognese collector Ulysse Aldrovandi (1522–1605), a new woodcut of his specimen was inserted amongst the exotic lizards.Footnote 28 Similarly, plate 53 of Albertus Seba’s luxurious collection catalogue, Locupletissimi rerum naturalium... (1734), shows a pangolin and snake extruding their long reptilian tongues.Footnote 29 In some works, this identity extended beyond physical comparisons: Clusius’s Lacertus peregrinus was classified amongst the egg-laying reptiles in some late seventeenth-century taxonomies. In John Ray’s Synopsis animalium quadrupedum (1693) Clusius’s Lacertus alteri peregrini was included amongst the oviparous quadrupeds “on account of its form.”Footnote 30

The challenge of defining the pangolin was bound up with the puzzle of its nature, provenance and form. The fact that Bontius’s fish-like “scaly turtle,” that he recorded in Batavia, was never identified with the “scaly lizard” demonstrates this ambiguity well.Footnote 31 Strange, scaly quadrupeds were sometimes linked to more identifiable “Indian lizards.” For example, amongst descriptions of various lizards in his Historiae animalium de quadrupedibus oviparis (1586), Gessner described “animals similar to serpents” in “Oriental India” with four feet and very long tails. These were similar to the Hyuana and Bardato (armadillo) of Occidental India, themselves “four footed serpents” according to the Italian polymath Girolamo Cardano (1501–1576).Footnote 32 This may perhaps be a reference to a pangolin-like creature but remains ambiguous.

While early modern travellers tried to depict exotic beasts as distinct and unique, scholarly descriptions tended to draw their accounts of the beasts’ forms and symbolic attributes from other animals in order to assimilate them.Footnote 33 The Indian Lizard was like a snake or lizard, but also like creatures such as the armadillo and anteater. Just as partial specimens reached Europe more often than whole animals, so it was that particulate descriptive tropes and images circulated, rather than whole, well-defined creatures. Though certain tropes were repeated between seventeenth-century texts, hitherto the animal had not been explicitly assembled by naturalists into a “set-piece” form. In contrast to the ubiquitous armadillo, pangolins did not appear in the frontispieces of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century cabinet catalogues: they would not have been an easily identifiable item in an idealised depiction of a collection.

Apart from the pangolin’s ambiguous identity, there was also much ambiguity regarding its origin. Clusius offered no origin at all. Piso had ascribed a specific Taiwanese origin to the example in his work, but also identified it as an “Indian lizard.”Footnote 34 The creature remained entwined with several other “Indian lizards” and the “Taiwan” and “Indian origins were used interchangeably: in effect synonymously.Footnote 35 In Piso’s 1658 De Indiae, this scaly animal was one of the group of wonderful natural things that came from the East, a region traditionally believed to be replete with wonders.Footnote 36 This volume was a new edition of the Historia naturalis Brasiliae (1648), which Piso extended to include material on the East as well as West Indies, in particular Bontius’s published and manuscript materials.Footnote 37 Piso’s editorial interventions and ambiguous presentation of material by the other deceased authors, both his naturalist-astronomer colleague Georg Marcgrave (1610–1644) and Jacobus Bontius, had the effect of effacing the distinctions between the two Indies, with fascinating effects on the origin and fate of the pangolin.

In these seventeenth-century natural histories, the pangolin was, in effect, delocalised, its particular origins were generalised. Though many pangolins seem to have been transported back to Europe from a variety of places, these specimens were rarely given specific provenance. The seventeenth-century “scaly lizard” was a highly generalised Oriental beast, or set of beasts. The case is not unique. There are other examples of such treatment in natural history texts, such as the flightless dodo. This bird had a very specific origin, the island of Mauritius. But in many seventeenth-century natural history texts it became an “Indian” bird that was used in Dutch iconography representing the far-reaching VOC trading enterprises and as a default element in Indian Ocean travelogues.Footnote 38 In both the cases of the pangolin and the dodo, “India” was therefore less a geographical localisation, than an identity which carried implicit attributes, not a geographical referent but a signifier of exoticism and the symbolic correlates of the East.Footnote 39 Neither animal was used as a cartographical symbol, yet they were both exotics identified by and lending identity to the “Indies.”

Particular pangolins

Historians of colonial natural history are familiar with the idea colonial naturalists’ preference for “splitting” novel elements of nature, in contrast to the predilection for “lumping” of naturalists in Europe.Footnote 40 The pangolin case illustrates this well. While naturalists such as Clusius bundled several specimens together as “Indian lizards,” colonial naturalists portrayed singular pangolins as denizens of specific locations, such as Ceylon, Taiwan, Siam and Guinea. Natural history accounts in Europe effaced individual identities with the ubiquitous label of “scaly lizard,” travelogues identified the beasts they described with local names. The animal was reported as being called Lin by the Siamese, pangoelling in China, Sumatra, Java, and Malaka, allegoe in Malabar and quogelo in Guinea, though published travelogue descriptions were almost entirely unconnected with one another, and only rarely used in natural history works.Footnote 41

What has been less examined is how the contrast between “lumping” and “splitting” can be used to understand the relationship between Europe-based naturalists at centres of accumulation and learned travellers as sources of wonder-filled travelogues. Here too, the pangolin is an illustrative case. There were strong economic and political reasons for travellers not to associate these things with the creatures written about by other naturalists, nor to translate the creatures from one group to another. The “devil” of the Dutch settlers was not the same thing as the Chinese pangoelling or Guinean quogelo, and these separate entities were more valuable as divided wonders. In contrast, in the European centres, there was strong economic pressure on naturalists to assimilate and amalgamate these different things, making products for the market in exotics.

The first identifiable account of a pangolin in the field was in the famous Itinerario (1597) of the explorer, Jan Huyghen van Linschoten (1563–1611). He described “a fish of most wonderfull and strange forme” taken from the “River of Goa” covered in “scales a thumbs breadth, harder than Iron or Steel.” When “hewed uppon,” it rolled into a ball and could not be prised open by force or “anie instrument.” It was only when “let alone” that “hee opened himselfe and ranne away.”Footnote 42 Though Linschoten’s work was very influential as the first extensive Dutch publication describing Asian trade and nature, as well as valuable shipping routes, his account of the pangolin was not used by any subsequent authors. It is not the discovery story of the scaly lizard.

Nearly a century later, in Siam in the 1680s, the French Jesuit missionary Guy Tachard (1651–1712) described a reptilian, scaly herisson (hedgehog) that he encountered, called bicho verghonso (shameful insect) by the Portuguese. It had a snake-like tongue and was cold-blooded when he dissected a freshly killed specimen. Yet, those he had seen alive rolled up when scared, and his dissection showed the creature to have young in its uterus. When born, these young rode on the base of the mother’s tail.

In the 1720s in Guinea, the French cartographer and navigator Reynaud des Marchais (1623–1728) described the scaly quogelo that defended itself against predators by gathering itself into a ball. It ate delicately, extending a long tongue covered in an unctuous liquid to catch ants, just like the anteater. He attested that this animal was “not the least bit naughty or malign, it attacks nobody.” He reported that “the Negroes assault it with baton blows, skin it, sell its white skin and eat its flesh” which was “white and delicate,” despite its diet of “musky” ants.Footnote 44

These strange creatures added cachet to travellers’ travelogues, and the detail with which they were depicted validated their wonderful natures.Footnote 45 Few of these accounts were included in scholarly tomes, and they rarely referred to one another. The herisson, pangoelling or quogelo experienced and related by one traveller was certainly not that experienced by another. It followed that anything like a biogeography, a systematic relationship between the pangolin and its regions of origin, was constructed almost entirely by naturalists in Europe. Significant geographical attributions were made once creatures had been extracted from one or more locations, and were generated as part of the beasts’ cumulative identity. Accumulation, of things, ideas and pieces of information, mattered in the porduction of natural knowledge. This was not a case where eyewitness stories played the decisive role. Rather than the autoptic texts that contained reports of animals in exotic locations, it was the skinned or eviscerated objects shipped to European depots that were the tokens by which this creature, its nature, and the place where it originated were understood. This relationship was reciprocal: geography offered meaning to ambiguous objects, and these natural objects characterised their attributed regions of origin.

Devils and Innocents

In these seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century accounts, pangolins were both devils and innocents, their moral status dependant on a writer’s perspective. Naturalists in Europe understood the animal’s nature based on its reptilian affinities, while travellers abroad ascribed a variety of moral valuations to the pangolins they saw, focusing on behaviours, such as defensive curling or feeding habits.

On the one hand, the pangolin could be seen as an impossibly strong, aggressively-spiked devil that undermined colonial infrastructures. Some naturalists characterised the animal as a “devil” on account of its physical form and the “horrible scales” that it raised “when aggravated,” or because it dug up rice paddies and the foundations of houses.Footnote 46 Like a ballistic projectile when curled up, the pangolin’s iron-like armour was so resistant it could not be pierced by European weapons. Impenetrability was a characteristic often attributed to armadillo armour, an “armed beast” covered in plates “so hard,” that a “no Arrow can pierce them,” and the skins of which could be used for “warlike gauntlets.”Footnote 47 An advertisement bill for the White Elephant Menagerie in Amsterdam in the 1700s, for example, invited visitors to see a stuffed nigomsen duyvel that could suffocate “the biggest of elephants” by wrapping around their trunks like “strangler” snakes. This specimen had been killed en route to Amsterdam because of its troublesome habit of digging through stone floors.Footnote 48 The naturalist Jan Jonston, meanwhile, described how the “Tatus,” would lie on its back in the rain, collecting rainwater to entice thirsty deer to drink, allowing the wily armadillo to snap its shell’s shut on the deer’s nose. If “not tied” the tatus was unstoppable: “he mines through all the houses, and towns, and gets away,” when “chased” always “flies at the hunter’s breast” to wind him.Footnote 49

On the other hand, the animal could be a harmless creature in dire need of the protection its scales offered. Travellers such as des Marchais described it avoiding danger and eating nothing but troublesome ants and worms. Indeed, he suggested that pangolins could be valuable for the control of insect infestations.Footnote 50 The Royal Society’s Secretary, Nehemiah Grew (1641–1712), described the Society’s “scaly lizard” specimen in a catalogue as “a most tame and innocent Creature,” in need of armour to defend itself, being “fearful and innocent.”Footnote 51 It used its scales to wound only animals seeking to attack it.Footnote 52 In this way, the pangolin’s formidable armour became part of a natural balance, where the vulnerable were given means of protection. Similarly, the armadillo was described by Samuel Purchas as a vulnerable creature with affinities to the turtle or hedgehog, “creeping through the bryars and bushes” and “not very well able to runne,” that required scaly protection for its toothsome white flesh. When tame, they could be bred in the household as long-term domestic pets.Footnote 53

The moral characteristics ascribed to exotic creatures were not insignificant attributions. Creatures of colonised regions, in particular, embodied colonial anxieties and prejudices: flora and fauna came to stand for the predicaments of colonisers, and details of their features took on the character of regional political dilemmas. Stephen Greenblatt’s important study of the early texts of Columbian encounters with New World indigenes shows how Native Americans were depicted as both innocents to be given the gift of Christianity and cannibals to be subdued through “liberating enslavement.”Footnote 54 Other scholars have explored the production of politicised natural histories, in which plants and animals take on the ambiguous natures of humans in colonial regions. Ethnohistorians Michael Dove and Carol Carpenter, for example, analyse mythopraxis in seventeenth-century colonial natural histories of the upas tree of the East Indies. In the work of VOC botanist, Georg Eberhard Rumphius (1627–1702), the tree was the deadly “poison tree,” emblematic of the colonial struggles in the region with both people and nature. Changes in colonial interactions and perceptions led to concomitant shifts in the portrayal of the upas.Footnote 55 These political biogeographies were closely linked to traditional Hippocratic ideas of regions’ effects on their inhabitants: exotically rich but potentially dangerous places produced beasts that were both edible innocents and warlike, plants that could be medicinal or lethal.Footnote 56

The function of exotic animals as emblems of colonial activity has not yet been considered in great depth. A creature such as the pangolin offers a rich example, not without parallels amongst both other exotic and more familiar creatures. It combined aggressive reptilian spikes and suffocating force as well as a fearful mammal-like form, its weakness armoured by a benevolent Nature. It is tempting to understand the moral force of the pangolin in just the sense that Greenblatt has proposed in readings of colonial accounts of indigenes’ violence and vulnerability. The pangolin’s constructed ambiguity reflected the duality of colonial aggression and righteous European mastery experienced by the Dutch. It also embodied the dichotomy between the ferocity of ambitious colonisers and the fear of the potentially potent colonised.

Much recent scholarship illustrating the situation of the Dutch in Asia during this period makes it possible to consider the geographical locations and moral attributes of the pangolins alongside the struggles experienced by traders and colonists there.Footnote 57 The Dutch base in Taiwan in the 1620s and 1640s, in particular, was a crucial but precarious trading position for which the Portuguese and Chinese powers also contended.Footnote 58 The dyvel that Piso published, undermining the Dutch in their attempts to claim Taiwan by digging up fields and the very foundations of their buildings there, was another obstacle against which they had to battle violently. The pangolin was also called Ceylonsche dyvel (devil of Ceylon), reflecting the perceived threats to Dutch attempts to obtain and maintain this important Indian Ocean trading base from the 1630s. The sharp-clawed pangoelling, described in the 1720s by the Dutch VOC minister in the East Indies, Francois Valentijn, was a threatening beast that undermined floors and houses with its incredibly rapid digging. It had a scaly hide that provided the raw materials from which opposing forces such as the Chinese and Javanese could create armour.Footnote 59 Like Rumphius’s deadly upas or ‘poison tree’ that tipped the lethal darts of Ambonese natives, this timid creature’s defenses supplied the armoury of the forces opposing Dutch operations.Footnote 60

There are other examples of moralised and politicised animals. In Dutch representations of the dodo, it became a bloated creature that was barely able to walk and had a gluttonous appetite, easily read as a symbol of the moral dangers of the consumptive VOC enterprise.Footnote 61 Similarly, birds of paradise from New Guinea were initially characterised as legless angelic beings, associated with the spices of the East Indies and often symbolising a lofty and ascetic life in books of emblems.Footnote 62 The birds were re-characterised as legged and ferocious carnivores, however, around the time that the Dutch enterprises in South East Asia became increasingly bloody and untenable. The pangolin as either gentle, protected innocent or spiky, aggressive devil encapsulates just such perspectives in colonial geographical perception. The armadillo’s striking shell was similarly a characteristic embodying such a dichotomy, “usefull both in warre and peace.”Footnote 63

Armadillos of the Orient and Occident

Unlike the pangolin, the early modern armadillo was first understood as a localised animal. It appeared in mid-sixteenth-century natural histories of South America, such as the works of Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés (1478–1557) and Francisco Hernandez de Toledo (1514–1587), These early descriptions from writers located both in the Americas and in Europe were used as authoritative accounts for the next century.Footnote 64 The armadillo was a prevalent cartographic image and frequently represented amongst other typical American creatures in the paintings of artists such as Frans Post (1612–1680). They were also very common cabinet specimens, and preserved armadillos were often pictured in the frontispieces of cabinet catalogues.

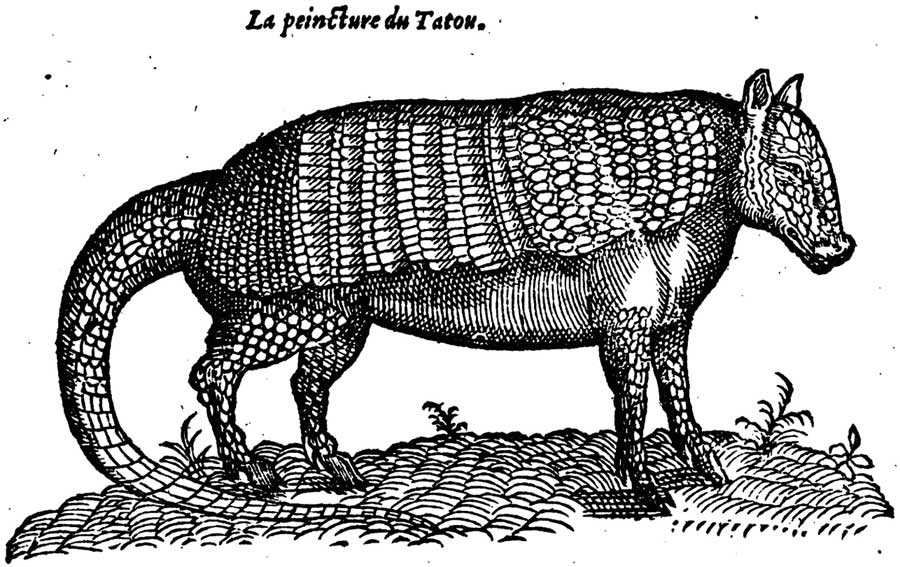

Some specific descriptive tropes were strikingly persistent. In Oviedo’s Sumario de la Natural Historia de las Indias. (Toledo, 1526), for example, the Encubertado (armadillo) was described as “just like an armoured horse, its body completely covered on all sides.”Footnote 65 This image was echoed by other writers, and many of the visual representations of the animal took this description literally, such as in the illustration of Pierre Belon’s Les observations (1553), showing a long-legged equine creature squinting from under its mail.

Stefano Della Bella’s didactic playing cards from 1644 feature an America card in which a female personification of the continent rides a chariot drawn by harnessed armadillos.Footnote 66 It seemed apt, in a period of militant European warfare in the Americas, that the armadillo be seen as a miniature armoured horse.Footnote 67 In their defensive rolled postures, these cuirassed mammals resisted exploitation for food and their carapaces were used to make gauntlet-like Caramenos by the indigenes.Footnote 68 Like the scaled pangolin, these denizens of the New World were always armoured, a militarised nature that both reflected and resisted colonial activities.

The prevalence of armadillo specimens in European collections from the mid-sixteenth century, the authoritative corpus of sixteenth-century natural histories of the Americas, and the many iconographic uses of the armadillo as a symbol of America have all sustained an historiography that treats the armadillo as a straightforward piece of Americana.Footnote 69 However, juxtaposition of the natural histories of the armadillo and of the pangolin reveals a different story. In his 1605 description of the armadillo, Clusius distinguished three forms, gathered from his translations of two older sources and specimens he knew of. Clusius had access to West Indian material through his connections with traders, prominent figures in key trading port towns like Enkhuizen, and his colleagues at Leiden University.Footnote 70 One of these sources was Clusius’s translation of the Spanish physician Nicolás Monardes’s Historia medicinal...Indias Occidentales (1565), who reported that armadillo tail, ground and made into pellets, cured ear ailments when placed into the ear canal.Footnote 71 The other primary source was his translation of Pierre Belon’s Les observations... (1553), describing his travels in the Levant.Footnote 72 Belon had reported seeing Tatous, unmentioned by the ancients, in the markets of Turkey, said to have been brought from “Guinea and the New World.”Footnote 73

Belon’s description suggests that armadillos were transported not only to Europe from America, but also to the Middle East by the mid-sixteenth century. It is likely that these creatures were circulated on slave trade routes between Guinea, the Americas and Europe. They may have been brought from South America to the focal trading ports in southern Europe, before being traded to the Middle East. Monardes certainly had lucrative interests in slave trading, alongside his importation of exotic naturalia.Footnote 74 Like pangolins, armadillos were commodities that circulated within their areas of origin as well as in more distant locations. Quite apart from the culinary value that they had and still have, the animals’ carapaces were useful materials for making “purses,” armor and other objects.Footnote 75 In both Europe and the Middle East armadillo shell was used as a medicinal simple, and perhaps for more decorative purposes.

The origins of objects from East and West Indies were sometimes confused as a result of the indirect routes by which these things were taken to Europe.Footnote 76 The West Coast of Africa, in particular, was an important trans-shipping centre for the trade routes from both the East and West Indies.Footnote 77 From the 1620s, the WIC took over several of the Portuguese trading posts along Africa’s West Coast, as well as setting up their “Garden” at the Cape of Good Hope from the middle of the century.Footnote 78 Armadillos travelled on slave ships just as pangolins were auxiliary cargoes on ships carrying valuable freights of spices. Their journeys were subject to the considerations of these primary trading enterprises. Compare the effects of transshipping on the obscurity of the origins of the “turkey bird.” It was called the kalkoen (Calicut-bird) in Dutch, or gallum Indicum (Indian bird) in Latin, obscuring its North American origin.Footnote 79

Shipping patterns were one of the factors that contributed to the expansion of the armadillo’s perceived region of origin from the mid-sixteenth century. Later accounts asserted that there were armadillos that lived in the Orient and Africa. For example, Clusius reported that the tatu was brought from “different regions of the world.”Footnote 80 Aldrovandi’s 1645 De quadrupedibus... claimed the armadillo was supposedly also found in Guinea and India.Footnote 81 In De Indiae (1658), Piso altered Georg Marcgrave’s original 1648 description of the tatu. While Marcgrave’s armadillo had been a creature located where he worked in Dutch Brazil, Piso’s editorial additions claimed that this “animal of extraordinary form is distributed not only in the Occidental, but also in the Oriental regions.”Footnote 82 Piso’s 1658 publication conflated the East and West Indies, mapping the reach of the global Dutch enterprise by amassing the exotic riches gathered from all the regions that it controlled into one volume. This generalised biogeography echoed the metaphorical connection between East and West Indies, both being regions filled with natural wealth and marvels. In this, it certainly bears out Schmidt’s work portraying the Dutch Republic as the seventeenth-century European entrepôt for exotic goods and producer of globalised exotic merchandise.Footnote 83

An armadillo that was not only an American but a globalised exotic from both East and West was of much greater value for Piso’s publication. Greenblatt has described the distinction between the commodity-based “extractive capital” and virtual “mimetic capital” in the valorisation of exotic sites, but this distinction was not always impermeable. Exotic creatures like armadillos were real, saleable items. Mimetic representations, such as books and maps, were also highly? saleable, and the appearance of these creatures in such works embodied other commodified riches acquired in the Americas.Footnote 84 Drawing on the “extractive capital” garnered from both Indies, Piso accentuated the “mimetic capital” of the depicted creature. Schmidt’s work shows how the very indeterminacy and imprecision of the presentation of circulated “exotic icons” served the different agendas of those representing or collecting them.Footnote 85 The armadillo became just such a mobile and malleable “icon” over the seventeenth century.

Global armoured mammals and the Great Chain of Being

From the mid-seventeenth century, characterisations of the armadillo and pangolin both shifted. Little changed in the descriptions of the animals’ physical forms, but the way in which these animals were presented as exotic symbols changed as their identities became intertwined. Their perceived regions of origin spread, and their symbolic roles in natural history texts and other publications became enmeshed. The characteristic orb-like forms of these shelled animals, when rolled up defensively, both distinguished them and made them globally interchangeable.

In later accounts, as the number of armadillo types increased in works of classification and collection catalogues, so did references to armadillos occurring in the East Indies, Africa, and other eastern locations. Similarly, the pangolin’s ascribed origins were expanded from the Oriental to encompass the Occidental Indies. In some publications, the two animals were described indiscriminately.

For example, in Robert Hubert’s 1664 catalogue of his collection at the “Musick House at the Miter,” he mentioned armadillos from the East and West Indies, and even another sort of “Armadillo of the East India that was presented King James for a Rarety.” He also mentioned “A B[...]gelugey... a creature of some parts of Africa, a kind of Lizard, that hath great scales like a fish,” possibly a pangolin.Footnote 86 In his 1734 catalogue, Albertus Seba described specimens of the tatu d’Afrique and tatu Orientalis.Footnote 87 In Seba’s pangolin descriptions, not only were two animals that looked very different treated as one, but they were also said to be called the “Tatoe by the Brazilians” and “armadillo” by the Spanish. Seba’s catalogue was influential, used by many subsequent natural histories. John Hill’s History of Animals (1752) described seven types of Dasypus (armadillo), some of which originated in Africa, and the East Indies, others in South America. He also included the ‘scaly lizard’ from both the East Indies and South America.Footnote 88 Other authors, such as Mathurin-Jacques Brisson in his Regnum animale (1756–62), described pangolins from Brazil, as well as Formosa, Java and other specific locations, or else omitted the pangolin as an individual creature and described types of armadillo also called a Devil of Taiwan or scaly armadillo.Footnote 89 Authors of natural histories and collection catalogues frequently likened “scaly lizard” specimens to other inanimate objects in collections that would have been at hand: ivory, small caskets, shells and pine-cones. Both the pangolin and armadillo shared this lizard-like scaled nature, so were often classified together in catalogues, frequently placed next to the lizards that they resembled.Footnote 90

In his magisterial Histoire Naturelle (1749–88), the French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707–1788) criticised the accounts given of these two creatures in taxonomic works. He argued that they relied too heavily on the descriptions of ignorant travellers or by collectors, who were often misinformed by the unreliable purchase history of items.Footnote 91 He posited that such conflations were caused in particular by the shipping of armadillos via Guinea as well as the ambiguous name of “scaly lizards.”Footnote 92

Buffon distinguished between the pangolin and the armadillo as Old and New World creatures, and determined two definitive types of manis, distinct from the “lizards” because of their lack of scales on “throat, breast or belly” and hair or smooth skin on their underparts. The short-tailed manis or pangolin and the smaller long-tailed manis or phatagin originated in Africa and the East Indies respectively.Footnote 93 Buffon also distinguished seven types of described armadillo. Unlike most other taxonomists, who focussed on the morphological aspects of creatures to categorise them, Buffon was intensely interested in geography. He was a leading figure in the attempt to differentiate the Old and New Worlds, closely engaged in a project of zonal distinction, including the definition of Eastern and Western faunas.Footnote 94 His project was essentially opposed to that of Piso, seeking to divide up the globe by typified traits and inhabitants, rather than to globalise “exotic icons.”

Biogeographical interests were not the only basis for the conflation of these two animals. Buffon’s account highlights the descriptive parallels shared by the pangolin and armadillo from the early seventeenth century, as well as the cosmological position they came to share. Apart from their shelly armour, that distinguished them from other fur-covered mammals, they were both metonymically linked to creatures such as the anteater, hedgehog and pig. The armadillo was covered “like turtles, craw-fish etc., with a solid crust” while the manis was “armed with scales like a fish.” They occupied a linking position in the Chain of Being, acting as intermediate forms between the different types of quadruped, cold- and warm-blooded. The “essential differences” distinguished “them from all other quadrupeds” so much, that they were almost a “species of monsters” with an “odd form” like “an intermediate class betwixt the quadrupeds and reptiles.” They were “exceptions of nature” as well as “gradations calculated to join in a general chain, the links of the most distant beings.”Footnote 95

It is easy to expect that intermediate or composite forms proved taxonomically troubling to early modern naturalists, but these scholars maintained much more relaxed cosmological boundaries than many historians assume. The pangolin and armadillo should not be understood as disruptive, unclassifiable entities. Rather, like other “monstrous” creatures such as the flightless dodo, they acted as new links that filled specific places in the Chain of Being. They were easy to place taxonomically, not despite their strange scaly nature, but precisely because of it. This transitional role was voiced in Thomas Pennant’s History of quadrupeds (1771), in which he wrote “these animals approach so nearly the genus of Lizards, as to be the links in the chain of beings which connect the proper quadrupeds with the reptile clans.”Footnote 96 They were examples of Nature’s plenitude, and the more fantastical examples of these interstitial links in the Great Chain were expected to be located in the more extreme locations of the globe.Footnote 97

Conclusion

The taxonomic reconstruction of the pangolin and armadillo as intermediate forms involved both explicit conflation and implicit symbolic association. Their biogeographies were similarly conflated, acting as fluid emblematic characteristics that shifted over time. The pangolin was initially a strange Indian “scaly lizard,” the armadillo a clichéd symbol of Americana, yet both came to be classified as monstrous global exotics. The “India” of the scaly lizard became the “Indies” of the scaled mammals, both East and West.

The confluence of these animals reflects conjoined European perceptions of the two Indies. Such perceptions could be actively produced in texts such as Piso’s 1658 De Indiae, in which a marketable global vision was created to serve a particular audience. It could also be passively experienced as a result of the intermingling of the goods and symbolic attributions of the East and West Indies from the perspective of Europe. As Schmidt has argued, the multitude of novel things brought to Europe became part of the emblematic appropriation of the globe through their presentation in texts, maps and works of art that acted as virtual global cabinets.Footnote 98 Although strange creatures such as the pangolin were of symbolic importance to people in places whence they originated or to which they were traded, it was especially in early modern European markets, collections and studies that so many of these things came together, to be re-assembled into a hybrid global worldview.

The amalgamation of these two creatures was, in part, the result of imperfect information transmission along densely networked global trade routes. Physical things were not always simple to interpret, and could turn up in unexpected places. As objects moved across the globe as well as between Europe and its colonies, imagery moved, not always in a stable manner, between different publications and accounts. The scaly patina of the armadillo’s carapace made it difficult to distinguish textually from the scales of the “Indian lizard.” From the perspective of trade, they were functionally alike in many ways: bought and sold in parallel, the class of the “scaly mammals” was a primarily commercial construction. In a world where Nature was provided by God for the use of Man, the functions of creatures and places were crucial elements of their characterisations. Functional equivalences created perceptual elisions between the morphological and geographical distinctions we might make today. Even in the late nineteenth century, export records from Borneo and Siam described quantities of “armadillo” skins, also labelled sesik tenggling, (sisik tenggling is “pangolin” in Javanese) being sent to Europe.Footnote 99

The arguments of historians such as Cook and Schmidt provide powerful evidence of the ways in which early modern colonial activities and commercial trading enterprises such as the VOC were intimately linked with Northern European natural history.Footnote 100 Travellers’ interests lay in accentuating unique natural paticulars, while in the collections and libraries of Europe, there were pressures to construct ambiguous things within existing perceptual frameworks and as recognisable commodities.Footnote 101 The relationship between commodity trade and natural history does not mean, however, that the emblematic value of exotic creatures was diminished. The New World, made available through exploration and trade, was interpreted and interpolated in European cosmological frameworks in publications and collections. Integral to this process was the making of exotic commodities, valued in part for the “mimetic capital” they embodied.Footnote 102

Though commodified, animals, or more commonly, their transformed body parts and relics, were not mere collectible ephemera in the early modern period. They constituted a substantial portion of the material coming from distant parts of the world, making them central to the European experience of these locations. As Daniela Bleichmar has argued, most “Europeans came into contact with the New World in Europe: colonial science was often enacted at home, not abroad.”Footnote 103 Animals also shaped the European experience abroad, affecting the practicalities of colonial endeavours, becoming emblems of these enterprises. Such reciprocal and malleable relations between human and non-human creatures, both transported physically and virtually, speak to many of the themes in the field of animal studies, which integrates work from many areas, including history of art, anthropology and literature studies.Footnote 104 Lorraine Daston and Gregg Mitman recently argued that animals so not act just as passive symbols, they “do something.”Footnote 105 Clearly, the “devils” described above, tunnelling under buildings and farms in Dutch colonies acted in a physical sense, but they also were constructed to enact colonial conflict.

The historian William J. Ashworth describes how the “allegories, mythologies” and “proverbs” of Renaissance naturalists “collapsed” in the mid-seventeenth century with the development of new objective practices.Footnote 106 The cases of the pangolin and armadillo, amongst many others, demonstrate the persistence of the emblematic genre well into the eighteenth century.Footnote 107 The tensions of early modern colonial projects are evident in the contemporary descriptions of flora and fauna from those regions. There was a clear relationship between Dutch imaginings of the Indies and the representations of peoples and creatures from this region.Footnote 108 The perceived hybridity of a creature such as the pangolin makes it a particularly valuable case, showing the potential co-existence of contradictory visions of a beast.

Crystallised in later works was another emblematic role for the scaled quadrupeds of east and west. Though Buffon geographically differentiated the pangolin and armadillo, he simultaneously associated them by ascribing them similar functions in Nature’s order. Exotic creatures were revealed signs of God’s infinite creation, rather than objects that did not fit. The emblematic use of creatures became more implicit, but the perceptions of a hierarchical natural world within which fascinating hybrid and anomalous creatures could be placed persisted well into the nineteenth century, as Harriet Ritvo’s work has demonstrated. The pangolin and armadillo were constructed as liminal forms between the different levels of being and between the distant colonial locations.Footnote 109

This paper has shown that objects serving as mutable mediators were an important resource for producing order in the natural world. Such objects were rarely subversive challenges to order, as Douglas’s anthropological work also demonstrates. Focus on the supply of exotic and liminal things reveals the economic and conceptual opportunities of ambiguity, in particular the potential for commercial differentiation, as Margócsy has shown. As a result, the assimilation and differentiation, “lumping” and “splitting” of new creatures were closely linked to processes of competition and differentiation.Footnote 110 The world could be understood through the things that came from its different regions, organic tokens that were constructed into a natural geography of the globe. Reciprocally, these natural things were characterised by the geographic regions over which they had been scattered by naturalists. Tracing the shifting biogeographical constructions of things transported over vast distances offers another way to access global interactions in a period of intense commercial activity, where the world-view was implicitly yet vividly symbolic.

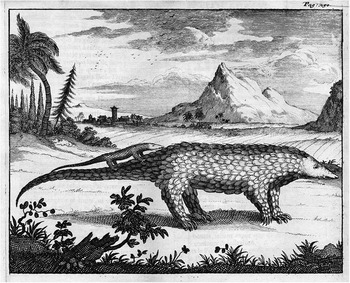

Figure 1 “Lacertus peregrinus squamosus” from Carolus Clusius’s Exoticorum libri decem (1605), appendix to bk. V, cap. XXI, p. 374.

Figure 2 “Lacertus squamosus” from Jacobus Bontius’s Historiae naturalis et medicae (1658), appendix to bk. V, cap. VIII, p. 60.

Figure 3 “L’Herisson” from Guy Tachard’s Second voyage du père Tachard et des Jésuites envoyez par le roy au royaume de Siam (1689), liv. 6, p. 250.Footnote 43

Figure 4 “du Tatou” like an armoured horse from Pierre Belon’s Les observations (1588), p. 467.

Figure 5 “Tatu seu Armadillo” from Willem Piso’s De Indiae utriusque re naturali et medica, (1658), lib. III, p. 100, showing its rolled and unrolled form.

Figure 6 “Lacertus peregrinus squamosus” (after Clusius) and “Armadillus sive Tatou” from Lochner and Lochner, Rariora musei besleriani (1716), Tab. XI.