Introduction

The current standard adjuvant treatment following breast-conserving surgery (BCS) for patients with early-stage breast cancer in the United Kingdom is whole breast irradiation (WBI), with 40 Gy to be delivered over 15 fractions.1 Post-operative radiotherapy lowers the incidence of local recurrence over a 5-year period by 4% (from 50 in 1,000 women to 10 in 1,000 with the addition of radiotherapy), and from a quality of life (QoL) perspective it has been shown that radiotherapy provision for this patient cohort reduces the rates of anxiety and depression by approximately 3·3% (from 30 in 1,000 women to 10 in 1,000 in those who undergo radiotherapy).1,2

When the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines were first established, WBI was recommended based on the evidence that it reduced the risk of local recurrence by half.2 However, local recurrence rates have fallen in the last 30 years, and now only 10 in 1,000 women with early-stage breast cancer who are at low risk and have WBI are expected to have a local recurrence and 50 in 1,000 who do not have WBI.1 As such, it is possible that the risks of WBI now outweigh the benefits for some patients, especially given that recurrence is more likely to occur in the relatively small area localised around the tumour bed, not the whole breast.2

While it remains an effective treatment in maintaining low local recurrence rates, the current issues associated with WBI include its time-consuming nature for the patient and the possibility that for some patients who are at very low risk of recurrence it is ‘over-treatment’ in terms of unnecessarily treating the whole breast which subjects them to the long-term side effects of radiation exposure with no gain in relation to reduced risk of recurrence.Reference Lehman and Hickey3,Reference Correa, Harris and Leonardi4 Radiotherapy as a concept has still been shown to be a valuable addition to the early breast cancer patient pathway, as evidenced by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group 9804 trial which found that patients with very early breast cancer who underwent radiotherapy following BCS were still less likely to develop local recurrence than those who were under observation without radiotherapy following surgery.Reference McCormick, Winter and Hudis5

As such, the role of partial breast irradiation (PBI) should now be considered to assess whether it can overcome some of the aforementioned issues with WBI, while conferring the same survival benefits and whether it could be offered as an alternative to WBI to a select group of patients. PBI is a potentially suitable alternative to WBI as it involves irradiating less normal breast tissue thereby possibly reducing both acute and late side effects that occur as a result of WBI such as skin reactions, poor breast cosmesis and an increased risk of developing secondary malignancies in the future. For women with a very low risk of recurrence, the late effects of WBI can present a more pressing concern than the chance of local recurrence, and subsequently, research has suggested that PBI could fulfil this role in terms of minimising recurrence through irradiation of the tumour bed where recurrence is most likely to occur while meeting the requirement of reduced harm to the patient by way of long-term side effects.2,Reference Julian, Costantino and Vicini6 Very low-risk patients are defined as women who are 65+ years old, with T1N0 tumours who are oestrogen receptor positive, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative and grade 1 or 2.1

One way to achieve PBI is the use of brachytherapy which can be delivered as interstitial brachytherapy, intra-cavity brachytherapy or through the implantation of permanent seed markers, although it is only offered in the United Kingdom in the context of research.Reference Lehman and Hickey3,7 It is not offered in the United Kingdom as the most recent NICE breast brachytherapy guidelines (2008) state that it is of uncertain safety and efficacy and factors such as toxicity, local control and the best method of delivery were unknown.7 The publication of these guidelines preceded large-scale studies of comparable Western populations into a variety of a multitude of brachytherapy techniques both in Europe and the United States of America but have not been revised to date.7,Reference Strnad, Ott and Hildebrandt8

Brachytherapy involves placing a radioactive source within the body and delivering a high dose of radiation directly to the tumour bed (plus a 1- to 2-cm margin) for a shorter period of time (between 4 and 5 days) in comparison to WBI.Reference Skowronek and Chicheł9 The aim of this PBI is to provide the same benefits to the patient as with WBI with regards to reduced local recurrence and increased overall survival, but to confer fewer negative side effects from the treatment onto the patient (as a result of less normal tissue being irradiated) and to necessitate fewer hospital attendances.Reference Skowronek and Chicheł9,Reference Correa, Harris and Leonardi4 It is estimated that using brachytherapy can reduce the overall volume of the breast irradiated by up to 50% compared to WBI which would benefit the patient in line with the Ionising Radiation (Medical Exposure) Regulations in which the As Low As Reasonably Achievable (ALARA). This principle states that the dose to normal tissue should be limited as far as possible.Reference Goyal, Kearney and Haffty10,11 A long-term side effect of radiation exposure is an increased risk of developing secondary malignancies in the future, and so the ALARA principle could be seen as more important than ever in a time when overall survival rates and life expectancy are increasing.Reference de Medeiros, Veiga, Neto, Abla, Juliano and Ferreira12 However, it is important to acknowledge that brachytherapy may only be suitable for a select group of patients with tumour size (must be less than or equal to 3 cm) and nodal involvement (must be N0) being some of the key limiting factors set out by the Royal College of Radiologist’s in their Consensus Statements.13 These selection criteria are based on the findings from a large multi-centre study carried out across Europe which concluded that their selective process was appropriate as a result of the low recurrence rate at 5-year follow-up, which followed earlier studies where poor local recurrence of up to 37% could be attributed to poor patient selection.Reference Strnad, Ott and Hildebrandt8,Reference Lehman and Hickey3 However, the study only included women that adhered to the above criteria and as such it cannot be conclusively stated that only this patient group would gain, as further research is needed with a wider sample of patient factors, for example, stage of disease to truly determine which patient group would benefit from being offered brachytherapy as an alternative to WBI.

It is important to address this topic because of the positive impact that a change in the approach to adjuvant radiotherapy could have on some patients with early-stage breast cancer in terms of limiting some of the negative side effects associated with radiotherapy. The aim of this review will be to critically evaluate the literature to determine if brachytherapy could be employed as an alternative to WBI for select patients with early-stage breast cancer. A secondary aim is to investigate if either treatment impacts favourably upon QoL.

Methods

It is imperative to construct a research question that is concise, feasible and answerable such that it is possible to undertake research that is beneficial to the field in question.Reference Agee14 The research question was firstly defined using the Population Intervention Comparison Outcome method to aid the search for relevant literature. When applied to the title of this literature review, patient applied to all patients with breast cancer undergoing radiotherapy; intervention applied to breast brachytherapy; the comparison was to patients undergoing conventional whole breast external beam radiotherapy; the outcome was measured in terms of overall survival and the impact on patient experience.

A review was needed for this topic because as life expectancy increases so too does the chance of late radiotherapy side effects impacting patient QoL. Evidence detailed in the NICE guidelines suggests that offering WBI to all women with early-stage breast cancer post-BCS may no longer have an acceptable risk–benefit ratio.1 As such, alternative methods should be sought, whereby patients still have the benefit of radiation, but the risk is reduced through less normal tissue being irradiated. A literature review was chosen as the method because it was necessary to summarise previous research and identify where the gaps in the evidence lie for further research.Reference Denney and Tewksbury15

Before conducting the search, the concepts were defined within the question (Appendix A). These concepts were made even more inclusive by searching using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) on the PubMed database. Using MeSH meant it was unnecessary to use the ‘OR’ Boolean connector to devise a plethora of alternative search terms for medical terminology as the database did this automatically.16 However, a limitation of this review is that only one database was used.

The concepts were combined using the ‘AND’ Boolean connector to create phrases that were used to search the PubMed database (Appendix B). PubMed was chosen as the database because it is specifically for clinical and medical literature, which was most relevant to this topic and is international in its scope. Furthermore, PubMed has multiple user-friendly functionalities to aid literature searches, including the aforementioned MeSH and other filters, for example, a search that only retrieves papers written in the English language.Reference Ecker and Skelly17

Further limits were then added to the search, for example, papers written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals during the last 15 years. The justification for all parameters is outlined in Table 1. Notably, exceptions were made for the time period when papers were found through other sources, for example, ground-breaking papers referenced in systematic reviews.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for literature search with justification

Grey literature was added to the results outside of the search strategy which included guidelines and snowballing was used when papers were found through referencing on other articles and where themes became apparent within the literature that subsequently necessitated exploration.

Articles found through the PubMed database search were appraised using Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network tool checklists that guide article appraisal to help limit researcher bias.

To improve this search strategy in future, it may be useful to employ the use of the truncation symbol (*) in order to limit the number of search terms, for example, surviv* could be used to find all mention of survival, surviving, survivor, etc.16 Additionally, to expand results slightly, it may be useful to search for acronyms such as QoL as well as quality of life and to limit the use of phrase searching.

Results

The results of the literature search are outlined in Figure 1 as a PRISMA flow chart.

Figure 1. Adapted from Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

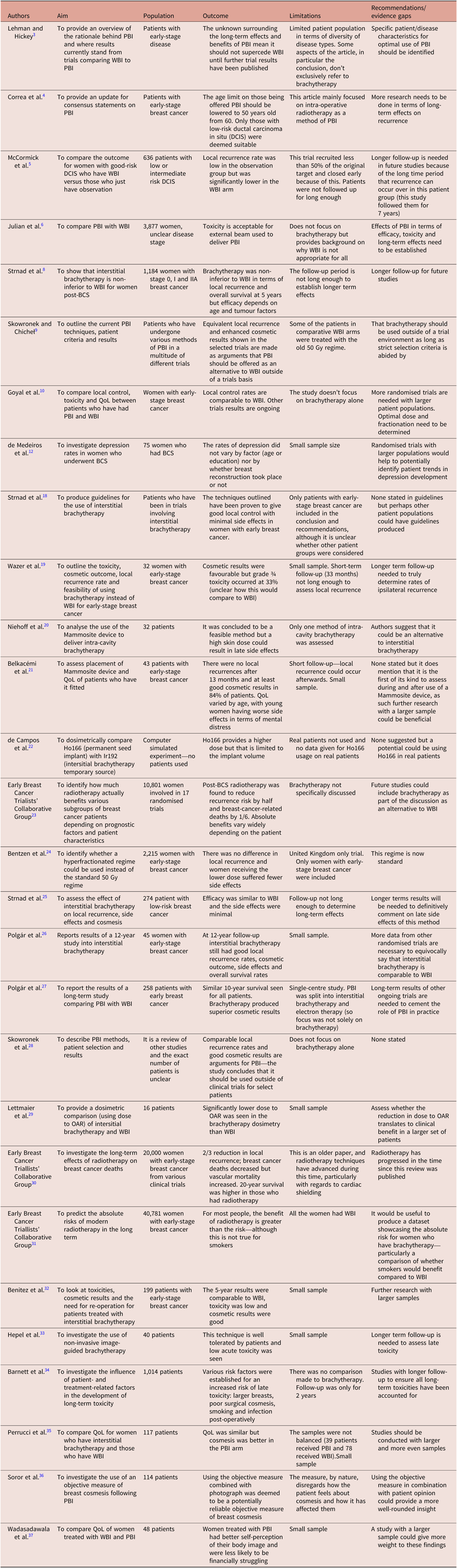

In total, 25 papers were used in the discussion, as outlined in the evidence table which can be seen in Appendix C. The key themes that arose were the variations between various brachytherapy techniques and the impact of both brachytherapy and WBI on overall survival and QoL. The majority of the studies used were conducted in Europe.

The results that were excluded were done so based on their irrelevance, for example, a small number of results were discussing brachytherapy for the treatment of prostate cancer, some focused on cost-effectiveness which was omitted as a point of discussion for brevity.

Discussion

There are three main types of brachytherapy: interstitial multi-catheter, intra-cavity and permanent seed implantation.Reference Skowronek and Chicheł9 However, the most widely used in practice is interstitial so this technique will be discussed more comprehensively in this review.Reference Strnad, Major and Polgar18

Interstitial multi-catheter brachytherapy

Interstitial brachytherapy involves inserting multiple flexible catheters into the breast to facilitate the movement of the radioactive sources from their storage medium into the patient.Reference Lehman and Hickey3 These catheters can be inserted either during BCS, whereupon brachytherapy is undertaken immediately, or into the surgical scar 2–4 weeks post-operatively, once definitive histopathology has been received.Reference Skowronek and Chicheł9 Advantages of inserting the catheters peri-operatively include enhanced tumour visualisation and the need for only one general anaesthetic, thereby reducing the risk to the patient. The necessity of only a single general anaesthetic may also be preferable for patients if they are given the choice as it would necessitate fewer hospital attendances. However, a potentially significant disadvantage is that the lack of histopathological information could result in an incorrect brachytherapy dose being given.Reference Skowronek and Chicheł9 The advantages and disadvantages of applying the catheters post-operatively mirror those of applying them peri-operatively: tumour localisation is through an X-ray or ultrasound and so less reliable; the patient is required to have another general anaesthetic; but the dosage will be prescribed with the additional knowledge of the exact histopathological diagnosis.Reference Skowronek and Chicheł9

A disadvantage of interstitial brachytherapy is that it can result in dose heterogeneity, leading to necrosis and subcutaneous toxicity in the treated area.Reference Lehman and Hickey3 Of the patients who experienced these side effects, the majority still had an excellent or good cosmetic score at 3 months post-brachytherapy, with the rest scoring no lower than fair.Reference Wazer, Berle and Graham19 However, it is unclear how a ‘fair’ cosmetic result compares to the result expected from WBI or how patients felt about the cosmetic results as the score was reported by a surgeon for objectivity.Reference Wazer, Berle and Graham19 However, these side effects are also noted in WBI and over a wider area as the field size includes the whole breast.

Intra-cavity brachytherapy

Intra-cavity brachytherapy is most commonly carried out using a Mammosite device that consists of a dual-lumen catheter with an inflatable balloon that is inserted into the surgical cavity during or after BCS.Reference Niehoff, Polgár and Ostertag20 The duality of the catheter allows one lumen for balloon inflation and the other to guide the radioactive source to the target.Reference Niehoff, Polgár and Ostertag20 Intra-cavity brachytherapy is a simpler alternative to interstitial brachytherapy, meaning less skilled expertise is required.Reference Skowronek and Chicheł9 However, concerns have been raised regarding adequate tumour coverage due to only a single applicator being used.Reference Belkacémi, Chauvet and Giard21

Permanent seed implantation

The implantation of permanent seeds is an alternative brachytherapy technique that relies on the placement of radioactive ‘seeds’ into the breast to emit low-dose radiotherapy directly into the target.Reference de Campos, Nogueira, Trindade and Cuperschmid22 The seeds are inserted post-operatively using hypodermic needles, which is an advantage of this technique in comparison with the aforementioned as a result of the lowered risk of infection.Reference de Campos, Nogueira, Trindade and Cuperschmid22 However, this technique has the disadvantage of conferring radioactivity into the patient for an extended period of time (rather than just the duration of the fraction), so caution should be exercised around young children and pregnant women. This would not be a concern with WBI or the alternative brachytherapy techniques so could impact negatively on patient QoL.Reference de Campos, Nogueira, Trindade and Cuperschmid22

Comparison of overall survival and local recurrence rates between brachytherapy and WBI

WBI as an adjuvant treatment to BCS improves overall survival both statistically and in a clinically significant way with a published overview of randomised trials showing that radiotherapy halves the risk of recurrence and lowers the rate of breast cancer-related deaths by one-sixth.23 One of the most important aspects to ascertain when considering interstitial brachytherapy as a safe alternative to WBI is that the outcome in terms of local recurrence and survival rate is not compromised.

A randomised trial carried out between 2004 and 2009 compared local recurrence and overall survival rates between women with early-stage breast cancer who were either treated with interstitial brachytherapy or WBI with a boost following BCS.Reference Strnad, Ott and Hildebrandt8 At 5-year follow-up, 1·44% of the brachytherapy treatment arm and 0·92% of the WBI had a local recurrence, and 4% of the brachytherapy arm and 6% of the WBI arm had not survived.Reference Strnad, Ott and Hildebrandt8 The study sets a ‘relevance margin’ of 3% so the results were not deemed to show a significant difference in local recurrence or overall survival rate between the brachytherapy arm and the WBI arm.Reference Strnad, Ott and Hildebrandt8 This study recruited a total of 1,328 patients who were then randomly allocated into the two treatment arms using an online generator in a central location which adds validity to the study through removing selection bias. Patients and investigators were not masked as to the treatment allocation: it would not have been possible to mask patients and it was not necessary to mask investigators as the measures chosen to evaluate the success of treatment were suitably objective (e.g., whether local recurrence occurred within a 5-year period from the date of BCS) so as not to be open to bias. Both treatment groups were similar at the start of the trial and less than the generally acceptable 20% of participants withdrew consent. Ultimately, 1,184 women completed the trial, with some swapping treatment arm because of contraindications so that 633 were in the brachytherapy arm and 551 were in the WBI with boost arm. The intention-to-treat principle was not used when analysing results because of investigator acknowledged bias that this could sway the results towards ‘no difference’, which was a key principle of this non-inferiority trial: this adds validity to the results. Additionally, it should be noted that the older 50 Gy regime was used for the WBI plus boost treatment arm, which is no longer the standard in the United Kingdom, although the Standardisation of Breast Radiotherapy Trial B trial did establish that the 40 Gy was clinically similar to 50 Gy in terms of local recurrence and overall survival before implementation and as such this does not completely remove the relevance of this study.Reference Bentzen, Agrawal and Aird24 The average age of participants was 62, which is representative of women who are diagnosed with breast cancer, and when analysis was carried out to compare each age subcategory, it was found that age did not influence the likelihood of local recurrence.Reference Strnad, Ott and Hildebrandt8 It was noted that the overall survival was worse in older participants but this was attributed to age-related co-morbidities.Reference Strnad, Ott and Hildebrandt8 The majority of patients (66%) were aged between 50 and 70 and none were younger than 40.Reference Strnad, Ott and Hildebrandt8 The sample was taken from 16 different hospitals in 7 European countries, adding to the representative nature of the patient population sampled.Reference Strnad, Ott and Hildebrandt8

The trial conducted between 2000 and 2005 found similar results to those described above, concluding that the efficacy of interstitial brachytherapy is comparable to that of WBI in terms of local control at 5 years.Reference Strnad, Hildebrandt and Pötter25 However, this study did not have a control arm of WBI for direct comparison making the results less reliable. The lack of control was presumably because the aim of the study was to assess the impact of multi-catheter interstitial brachytherapy (in terms of local control, toxicity and cosmesis) as a stand-alone adjuvant therapy to BCS, rather than to directly compare it to WBI. Their conclusion that brachytherapy was comparable to WBI was done generally without reference to specific findings. Furthermore, the mean age is not stated and the age range extended from 39 to 84 years, thus it is not clear whether the age of the sample as a whole is representative of breast cancer patients. In addition, the two treatment arms were dissimilar in some regards prior to brachytherapy, for example, there was variation in the type of BCS they had undergone, and whether they had had chemotherapy and hormone therapy: these factors make it difficult for comparison as the results may not be due to brachytherapy alone. Researchers did perform various statistical tests to verify cause and effect but in future it may be of use to limit variation in patient factors to increase the validity of findings.

A 12-year prospective study composed of 45 women with early-stage breast cancer treated with interstitial brachytherapy found that at 12 years the results in terms of local recurrence and overall survival were still comparable with those of WBI.Reference Polgár, Major and Fodor26 The relatively small sample is expected in a long-term trial where drop-out rates are generally higher. Although the sample is fairly representative with the mean age being 56 and the majority of patients aged over 50, this result still should not be generalised as a result of the diminutive sample. None of the patients received chemotherapy which adds validity to the findings as it makes it more probable that the results are due to the brachytherapy; however, it should be noted that 7 were prescribed Tamoxifen for a period of 5 years. The researchers concede that data from more prospective trials are needed before confirming brachytherapy as equivalent to WBI, even for a select patient group.Reference Polgár, Major and Fodor26

Another trial compared brachytherapy with WBI 3 years later. The study consisted of 258 randomised women, which, while still significantly larger than other samples, is relatively small compared to the number of women who are diagnosed with breast cancer annually.Reference Polgár, Fodor, Major, Sulyok and Kásler27 The 10-year local recurrence rate in the brachytherapy arm was 5·9% compared with 5·1% in the WBI arm, and the overall survival was 80 and 82%, respectively, using statistically objective measures.Reference Polgár, Fodor, Major, Sulyok and Kásler27 The author again conceded that the sample was too small for the evidence to be conclusive but made recommendations for further trials to prove the hypothesis that brachytherapy and WBI are equivalent.Reference Polgár, Fodor, Major, Sulyok and Kásler27

Quality of life issues with brachytherapy and WBI

Undeniably one of the key advantages of brachytherapy over WBI in terms of QoL is the accelerated nature of brachytherapy resulting in fewer hospital attendances for the patient over the treatment period. Shortened treatment times particularly have an impact on patients who work alongside treatment, live a long distance from the radiotherapy department or are less able to travel.Reference Skowronek, Wawrzyniak-Hojczyk and Ambrochowicz28 Performance status of the patient or patient choice in opting for this convenience could be a factor in a potential patient preference for brachytherapy over WBI.

Treatment with brachytherapy exposes organs at risk (OAR) to a lower radiation dose than WBI as a result of less tissue being exposed as dose penetration is less deep because of a sharp dose drop off not present in WBI.Reference Lettmaier, Kreppner and Lotter29 Restricting this dose to OAR limits the long-term side effects, for example, cardiotoxicity. The importance of which is outlined in a long-term toxicity study which found that patients treated with adjuvant WBI then had exponentially increasing mortality from other factors (excluding breast cancer) which was particularly evident at 20-year post-treatment.30 While this remains an important consideration, the age of this study should be taken into account as it pre-dated the use of heart-sparing techniques such as multi-leaf collimators for cardiac shielding. It has been estimated that the risk of heart disease developing as a late effect from modern radiotherapy is only increased 0·3% to the normal population.31

An additional QoL consideration for breast cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy is breast cosmesis following treatment because of the impact this can have on self-esteem, body image, confidence and relationships.Reference de Medeiros, Veiga, Neto, Abla, Juliano and Ferreira12 Multiple studies cite a good or excellent cosmetic outcome for patients who have undergone brachytherapy.Reference Polgár, Major and Fodor26,Reference Benitez, Chen and Vicini32,Reference Hepel, Leonard and Sha33 However, while the cosmetic outcomes are promising, a variety of studies including analysis of four randomised controlled trials conducted by NICE have not shown them to be superior to WBI outcomes.2

Proving that one technique is superior to another in terms of breast cosmesis may prove difficult as it is hard to exactly match the two treatment arms for participant factors. This is because a wide variety of factors can influence the aesthetic outcome of WBI including post-operative infection, smoking, age, body mass index, systemic treatments and multiple co-morbidities.Reference Barnett, Wilkinson and Moody34 For example, Barnett et al. found in their study that smokers were more likely to develop pigmentation and those who suffered from post-operative infection had an increased likelihood of developing telangiectasia and breast sensitivity.Reference Barnett, Wilkinson and Moody34 In this study, toxicity was reported by a range of means including photographs, assessments by clinicians and patient-reported means. This range of reporting techniques and particularly the inclusion of photographic evidence adds reliability to the findings through a degree of objectivity. In addition to aesthetic outcome, one study went so far as to say that for smokers with early-stage breast cancer, the risk of radiotherapy would outweigh the benefits, compared to their non-smoker counterparts with the risk of late side effects such as heart disease and lung cancer increasing from 0·3% for non-smokers to 1 and 4% respectively for smokers.31

Additionally, it is important to note that while early findings largely indicate that cosmetic outcomes for brachytherapy and WBI are equivalent, this is not the same for every brachytherapy technique or patient subset. For example, the intra-cavity brachytherapy technique was found to have worse breast cosmesis for patients where a skin spacing distance of more than 20 mm was not possible. 28% of patients with a skin spacing distance of greater than 20 mm had excellent cosmetic outcome at 2 years compared to 0% of patients with a skin spacing distance of 12–15 mm.Reference Belkacémi, Chauvet and Giard21

A 2015 study found that there was no difference in reported cosmesis between patients treated with WBI and those treated with brachytherapy when patients were self-assessing, but when physicians reported on cosmesis for the same group of patients the brachytherapy arm were found to have significantly better cosmesis than the WBI group.Reference Perrucci, Lancellotta and Bini35 This could be for a number of reasons including the clinicians having more experience in assessing a range of different aesthetics: the subjectivity of the measurement, the physician not being blinded as to which treatment the patient had undertaken and therefore acting under bias. QoL measures are notoriously hard to assess objectively as they often rely on self-reporting from patients.Reference Soror, Kovács and Kovács36 This issue was addressed in a 2016 publication which outlined an objective breast cosmesis scale (OBCS) designed specifically for assessing the aesthetic outcome of interstitial brachytherapy by using pixels on photographs to measure anatomical distances on the breast.Reference Soror, Kovács and Kovács36 Comparisons were made between the images of the treated breast over a median period of 3·6 years.Reference Soror, Kovács and Kovács36 It was concluded that the OBCS would be a credible option for analysing the aesthetic outcomes of interstitial brachytherapy.Reference Soror, Kovács and Kovács36 However, this is contentious given the sensitivity of breast cosmesis as an issue and it may be argued that discrediting self-reporting by relying on objective measures would invalidate the emotions of the patient thereby not providing compassionate care.

While it has been noted that brachytherapy is favourable to WBI in some aspects of QoL such as being less time-consuming, it has its own shortcomings with relation to an alternative host of local toxicities and the fact that it is an invasive technique, all of which needs to be taken into consideration when deciding who could benefit from brachytherapy as an alternative to WBI.Reference Wadasadawala, Budrukkar and Chopra37 Poor QoL during and after breast cancer treatment has been linked to higher rates of depression and anxiety in survivors; with long-term survival increasing, this is a particularly important time to focus on QoL issues.Reference de Medeiros, Veiga, Neto, Abla, Juliano and Ferreira12

Furthermore, when accounting for patient choice, people may prefer to opt for WBI simply because of the wealth of evidence into short- and long-term toxicity, rather than the comparable unknown for brachytherapy, particularly in relation to long-term side effects. Ultimately, patient anxiety over the unknown and a potentially more invasive alternative to WBI may negate the choice of brachytherapy over WBI.

Conclusion

In conclusion, while the role of brachytherapy in the management of early-stage breast cancer remains to be formally integrated in practice, it has shown promise in terms of early studies demonstrating equivalent local recurrence and overall survival rates to WBI.

With cancer therapies entering an era of personalisation, it is fitting that radiotherapy follows suit and research should focus on which patient subsets in particular would benefit from being offered brachytherapy as an alternative to WBI. It is equally important to identify if there is a subset of patients who would not benefit and if there are specific factors that would negate the use of brachytherapy over WBI. At this stage, research has identified that women with early-stage breast cancer would be most likely to benefit from brachytherapy in terms of an equivalent survival and local recurrence outcome but with superior cosmetic benefit compared to WBI. However, in part, this could be due to a lack of research into the effects of brachytherapy on those with more advanced disease and the role that factors such as the impact of performance status and various co-morbidities may play. Future research should focus on identifying if other patient populations could benefit; longer term follow-up than previous studies as this is frequently listed as a limitation and determining the optimal dose and technique for brachytherapy administration. Additionally, more research could be carried out into patient preference when choosing between WBI and brachytherapy, as balancing a potentially superior cosmetic outcome with the initial invasive nature of the brachytherapy procedure.

It is important that future research focuses on these factors in order to expand the evidence base and ascertain whether brachytherapy can be considered as a credible alternative to WBI for both survival and QoL.

Acknowledgements

The Radiotherapy and Oncology team at Sheffield Hallam University.

Appendix A. Initial search concept Table

Appendix B. Search terms used once MeSH filter was applied

‘breast cancer’ AND brachytherapy AND radiotherapy AND ‘quality of life’—24 results

Breast cancer AND brachytherapy AND external beam radiotherapy AND quality of life—18 results

‘breast cancer’ AND brachytherapy AND radiotherapy AND toxicity AND ‘quality of life’—7 results