Introduction

Suicidal and self-harming behaviours remain major challenges facing mental health services. The World Health Organization estimates that 800,000 people die from suicide every year and many attempt suicide or self-harm (WHO, 2014). Research in this area has increased significantly over the years (Lester, Reference Lester1983, Reference Lester1992, Reference Lester1997, Reference Lester2000b). A large part of this research is focused on examining risk (and protective) factors for the behaviour (Klonsky et al., Reference Klonsky, May and Saffer2016; Rogers, Reference Rogers2001). However, even complex models of these factors had very little predictive power (Goldstein et al., Reference Goldstein, Black, Nasrallah and Winokur1991). Another source of complexity is that there is a range of self-harming behaviours, some with intent to die and others without. This distinction is complicated by the difficulty in measuring intent, leading to some suggesting a definition of ‘non-zero’ wish to die (O'Carroll et al., Reference O'Carroll, Berman, Maris, Moscicki, Tanney and Silverman1996). It is also complicated by the high co-occurrence of these behaviours (Dulit et al., Reference Dulit, Fyer, Leon, Brodsky and Frances1994; Nixon et al., Reference Nixon, Cloutier and Aggarwal2002; Nock et al., Reference Nock, Joiner, Gordon, Lloyd-Richardson and Prinstein2006; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Winchel, Molcho, Simeon and Stanley1992) and sometimes by similarities in risk factors (Andover et al., Reference Andover, Morris, Wren and Bruzzese2012; Gould et al., Reference Gould, Greenberg, Velting and Shaffer2003; Guerry and Prinstein, Reference Guerry and Prinstein2010; Wichstrom, Reference Wichstrom2009). This has led to the suggestion that these behaviours are part of a continuum of self-harm (Linehan, Reference Linehan, Maris, Cannetto, McIntosh and Silverman2000; Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Winchel, Molcho, Simeon and Stanley1992).

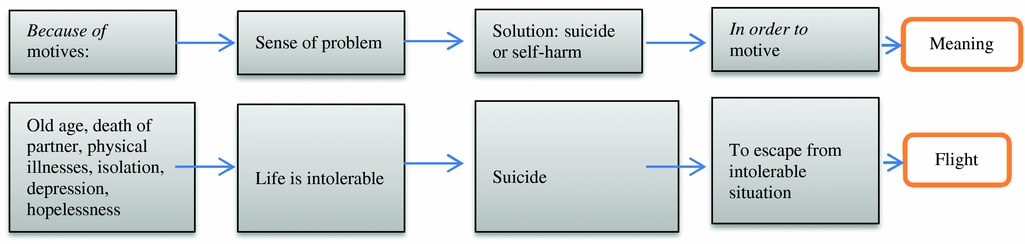

While studying correlates of the behaviour can improve our understanding of why some people engage in self-harming and suicidal behaviour, a more direct approach is to study its motives. This area has received less attention. May and Klonsky (Reference May and Klonsky2013) found only 14 studies on motives compared with thousands on risk factors. In addition, studies that examined motives did not explicitly address the difference between the because motives (the past events that have led to the behaviour) and the in order to motives (the future oriented goal of the behaviour) (Schütz, Reference Schütz1984). Understanding the motives behind the behaviour might inform the conceptual models of suicide as well as the assessment and management of individual cases (Klonsky et al., Reference Klonsky, May and Saffer2016). The distinction between the two types of motives would add more clarity to these conceptual models and would inform clinical assessment and interventions.

A number of theories have been suggested to explain suicide. A review and a critique of these theories are beyond the scope of this paper and can be found elsewhere (Jacobson and Batejan, Reference Jacobson, Batejan and Nock2014; Selby et al., Reference Selby, Joiner, Ribeiro and Nock2014). The motive of the behaviour is central to some of these theories. For example, the motive may be conceptualized as an attempt to end psychological pain through cessation of consciousness (Shneidman, Reference Shneidman1985), as an escape form an aversive self-awareness (Baumeister, Reference Baumeister1990), as a cry of pain (Williams, Reference Williams1997; Williams and Pollock, Reference Williams, Pollock and van Heeringen2000), because of hopelessness (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Steer, Kovacs and Garrison1985, Reference Beck, Brown, Berchick, Stewart and Steer1990) or to extinguish a negative state caused by emotional dysregulation (Linehan, Reference Linehan1993). Three recent models suggested different domains or stages in understanding the behaviour and more specifically the transition from suicidal ideas to suicidal acts. The development of suicidal ideation is thought to be caused by a combination of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness in the Interpersonal-Psychological Theory (Joiner, Reference Joiner2005); by defeat and entrapment in the Integrated Motivational-Volitional Model (O'Connor, Reference O'Connor, O'Connor, Platt and Gordon2011) or by pain and hopelessness in the Three Step Theory (Klonsky and May, Reference Klonsky and May2015). The move from ideation to action is suggested to be the result of the acquired capability to enact lethal self-injury in the first model or by a number of factors in the other two models.

Motives found in previous studies (Chapman and Dixon-Gordon, Reference Chapman and Dixon-Gordon2007; Holden et al., Reference Holden, Kerr, Mendonca and Velamoor1998; Kovacs et al., Reference Kovacs, Beck and Weissman1975; May and Klonsky, Reference May and Klonsky2013; Schnyder et al., Reference Schnyder, Valach, Bichsel and Michel1999) could be broadly grouped as internal, such as dealing with difficult or intolerable states of mind, or external, where the aim is to communicate something to others or to influence them. For example, Kovacs et al. (Reference Kovacs, Beck and Weissman1975) found two primary motives: escape from psychological pain and influence on the social environment with the former being associated with more serious attempts. Matthews (Reference Matthews2013) presents a cognitive behavioural model of suicide based on the general cognitive approach of Beck and colleagues, including the two motivational states of Kovacs et al. (Reference Kovacs, Beck and Weissman1975).

There are few measures of motives for suicide attempts or self-harm. The Suicide Attempt Self-Injury Interview (SASII) is an instrument that covers a number of factors involved in non-fatal suicide attempts and intentional self-injury including motives (Linehan et al., Reference Linehan, Comtois, Brown, Heard and Wagner2006). The Self-Injury Motivation Scale (Osuch et al., Reference Osuch, Noll and Putnam1999) measures motives for self-injury. It was based on in-patients who did not intend to kill themselves and items were based on clinical experience and empirical work rather than a systematic theoretical model. The Reasons for Attempting Suicide Questionnaire (RASQ) (Holden et al., Reference Holden, Kerr, Mendonca and Velamoor1998; Johns and Holden, Reference Johns and Holden1997) is another measure of attempted suicide. The factor structure of RASQ yielded two (Holden et al., Reference Holden, Kerr, Mendonca and Velamoor1998) or three (Holden and DeLisle, Reference Holden and DeLisle2006; Holden and McLeod, Reference Holden and McLeod2000) factors, where the motives are grouped as either internal or external (manipulative and extra punitive). May and Klonsky (Reference May and Klonsky2013) identified three limitations of the RASQ: the items do not cover the breadth of theories, it is based on a small sample of patients who overdosed, and the factor structure is uncertain. The Inventory of Motivations for Suicide Attempts (IMSA) (May and Klonsky, Reference May and Klonsky2013) was developed using patients who attempted suicide within the previous 3 years. It has 10 scales that cover recent theories of suicide and produced two factor structures: intrapersonal motivations and interpersonal motivations.

The questionnaire that we present in this paper is based on the theoretical work of Jean Baechler (Reference Baechler1979), who proposed a model of suicide using the Ideal Type methodology (Weber, Reference Weber1949). In summary, suicide is seen as behaviour rather than an act; as a means to an end, not an end in itself; and as a response to a problem (which could be internal or external). Baechler uses the term ‘suicide’ to cover all acts of self-harm, whatever the individual intended in terms of outcome (Baechler, Reference Baechler1979, pp. 8–20). In his analysis of suicidal behaviour, Baechler follows Schütz (Reference Schütz1984) in distinguishing between the because motive and the in order to motive of the behaviour; he bases his typology on the in order to motive on the basis that it gets us closer to the more immediate meaning of the suicidal behaviour (Baechler, Reference Baechler1979, pp. 53–55).

Following his analysis of case studies using the Ideal Type methodology, Baechler suggested eleven typical meanings, grouped into four general types. These meanings are ‘strategic simulations’ in that they reveal the internal logic of the behaviour or the end pursued. Each type has its own internal logic in that the means used is appropriate to the aim being pursued as perceived by the actor (although, as Baechler points out, the behaviour is not necessarily always rational) (Baechler, Reference Baechler1979, pp. 63–65). These meanings rarely occur in one pure form and more than one meaning will usually be operative in the suicidal act. Below are the definitions of these types but we refer interested readers to Baechler's book (Baechler, Reference Baechler1979):

Escapist :

-

1. Flight: to escape from a situation sensed by the individual to be intolerable.

-

2. Grief: loss of a central element of personality or way of life.

-

3. Self-punishment: to expiate a real or imaginary fault.

Aggressive :

-

1. Vengeance: to provoke another's remorse or to inflict the opprobrium of the community on him/her.

-

2. Crime: to involve another in one's own death.

-

3. Blackmail: to put pressure on another by depriving him/her of something he/she holds dear.

-

4. Appeal: to inform others that the individual is in some danger (cry for help).

Oblative :

-

1. Sacrifice: to save or gain a value judged to be greater than personal life.

-

2. Transfiguration: to attain a state considered infinitely better than life.

Ludic :

-

1. Ordeal: to risk one's life to prove oneself to oneself or to solicit the judgement of others.

-

2. Game: to play with one's own life.

There is already some empirical evidence for this typology. A study of 27 cases found evidence to support Baechler's typology (Smith and Bloom, Reference Smith and Bloom1985). Another study found the four general types of Baechler's typology were able to classify more than 86% of cases (Reynolds and Berman, Reference Reynolds and Berman1995). Baechler's typology has the potential to provide a more detailed analysis of suicidal motives than hitherto. We set out to develop and then test the psychometric properties of a standardized questionnaire based on Baechler's typology.

Method

Subjects and recruitment

Patients aged 16 years and over, who had attempted to harm or kill themselves in the last four weeks, were identified through lists of patients seen by crisis teams, lists of in-patients and through contact with other clinicians working in Lincolnshire Partnership NHS Foundation Trust and Derbyshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (Chesterfield site). Patients were approached personally or by telephone. They were given or sent the information sheet, the invitation letter and the consent form. Consenting patients were invited for an interview in the mental health units of the two Trusts. Those who were not willing to be interviewed but were still willing to participate were sent the questionnaires by post (in the Lincolnshire Trust only). Those who attended were invited for an in-depth interview for a qualitative arm of the study (not reported here). During interviews one of the researchers was present; however, the instruments were self-completed with no interference from the researcher.

Instruments

All the instruments used in this study are self-completed:

-

1. Demographic and clinical questionnaire: This was developed by the researchers and covered demographic data, details of current and previous attempts, clinical characteristics and conceptual views about religion and death.

-

2. Ideal Typical Meanings Questionnaire (ITMQ): This is the instrument that we aimed to validate. The items were generated by the first two authors (M.A. and M.M.) on the basis of their experience of suicidal psychiatric patients and their knowledge of the Baechler framework (Baechler, Reference Baechler1979). Items were developed to cover different aspects of each type. We excluded one of the eleven types from consideration: the Crime type, because the selected patient population was unlikely to contain this and because the in order to motive is not clearly identified. The questionnaire consisted of 53 items. Of these, only 46 items were to be included in the factor analysis. The rest were included to test different themes related to Baechler's theoretical work such as ‘the attempt as a means of solving a problem’; ‘living one's death in advance’ and ‘the public's view of those who self-harm or attempt suicide’. We chose a five-point Likert scale because this pattern is considered ‘more reliable, gives more stable results and produces better scales’ (Comrey, Reference Comrey1988). The items were scored from strongly disagree (with a score of 1), disagree (2), don't know (3), agree (4) to strongly agree (5).

-

3. Death Attitude Profile-Revised (DAP-R) (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Reker, Gesser and Neimeyer1994): This is a validated multidimensional measure of attitudes to death. It is scored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). It measures the following dimensions: fear of death (negative thoughts and feelings about the state of death and process of dying), death avoidance (the avoidance of thinking about death), neutral acceptance (death as a reality that is neither feared nor welcomed), approach acceptance (the view of death as a gateway to a happy after-life) and escape acceptance (death as escape from a painful existence) (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Reker, Gesser and Neimeyer1994). We chose this measure because the meaning of the suicidal act is significantly determined by the individual's conception of, and attitude towards death. In addition, this measure is used to test the concurrent validity of Baechler's Flight type with Escape Acceptance and Transfiguration type with Approach Acceptance, as we see these as conceptually related (Wong et al., Reference Wong, Reker, Gesser and Neimeyer1994).

Statistical analysis

Factor analysis was used as the main statistical technique. Factor analysis is a useful technique when a construct, such as the meaning of suicidal behaviour, is considered multidimensional (Clark and Watson, Reference Clark and Watson1995). We used common factor analysis with oblique (promax) rotation as we assumed that some of the factors will be correlated (Costello and Osborne, Reference Costello and Osborne2005). We chose common factor analysis, rather than the widely used principal component analysis, as our aim was the identification of latent constructs rather than data reduction (Floyd and Widaman, Reference Floyd and Widaman1995). The internal consistency of the ITMQ types was checked using Cronbach's alpha and average inter-item correlations. The latter was considered a more straightforward measure of internal consistency with a recommended range of 0.15–0.50 (Clark and Watson, Reference Clark and Watson1995). For each type of the ITMQ, a mean score was calculated by dividing the total score of the items by the number of items forming each type. Correlations between the types of the ITMQ and the dimensions of the DAP-R and other continuous variables were tested using Pearson's correlation coefficients. In addition, the relationship between the different types of ITMQ with demographic, clinical, religious views and concepts of death were tested using t-tests and one-way ANOVA: the results are presented separately. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 19 for Windows) was used for the analysis. Ethical approval was obtained from the Multicentre West Kent Research Ethics Committee (REC reference number 07/Q1801/18) and every participant gave written, informed consent.

Results

Sample

Demographic, clinical and other characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. In total, 147 patients participated in this study (91 from one Trust, and 56 from the other). Data were collected by interview (64, 43.5%) and by postal questionnaire (83, 56.5%). There were more females in our sample (99, 67.3%) than males (48, 32.7%). Age ranged from 16 to 87 years (mean = 35.6, SD = 13.7, median = 36.0). All those who declared their ethnic origin (136, 92.5%) were White. Patients who completed the questionnaires as part of an interview did not report any significant distress.

Table 1. Demographic, clinical and other characteristics of the sample

Factor structure

The responses to the 46 items of the ITMQ were subjected to common factor analysis. Thirteen factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1 were extracted and rotated to provide an oblique (promax) solution. These factors accounted for 68.6% of the variance. The scree plot showed that the curve flattened out after factor 8. Factorially complex items (items loaded 0.40 or greater on two or more factors) and items which loaded less than 0.40 on any factor were removed. The remaining 25 items were re-factored using the same procedures. This led to the extraction of eight factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1 which accounted for 66.9% of the variance. Bartlett's test was significant, p < 0.001 and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin index = .717, suggesting that data were suitable for factor analysis. The factor structure is presented in Table 2 and the co-loading of all items with all factors/types are presented in Table 7 (online supplement).

Table 2. Factor structure and reliability tests of ITMQ

The eight factors were very similar to the first eight factors of the initial solution and their interpretation was straightforward. The items that were designed to represent a certain type/meaning loaded highly on the factor representing that type or meaning with very small or negligible loading on any other factor. The first factor contained five items that represented both the Appeal and the Blackmail meanings and was therefore named Appeal/Blackmail (21.2% of the variance). Similarly, the second factor contained items representing Ordeal and Game types and was therefore named Ordeal/Game (five items, 9.5% of the variance. The remaining factors were as follows: Vengeance (three items, 8.5% of the variance), Self-punishment (three items, 6.4% of the variance), Sacrifice (three items, 6.0% of the variance), Flight (three items, 5.7% of the variance), Grief (two items, 5.1% of the variance) and Transfiguration (one item, 4.1% of the variance). The means and standard deviations of the eight types are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of the ITMQ types

Correlation between the ITMQ types

The intercorrelation matrix for the ITMQ types is presented in Table 4. Of note is the moderate correlation between the Appeal/Blackmail type with the Ordeal/Game type (correlation coefficient 0.44) and the Vengeance type (correlation coefficient 0.39).

Table 4. Intercorrelations of the types/meanings of the ITM

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed); *correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Reliability

Alpha coefficients of the different subscales (types) ranged from 0.70 to 0.80 apart from the Grief type (0.58), and the average inter-item correlations ranged from 0.38 to 0.58, suggesting adequate reliability (Table 2).

Concurrent validity

A moderately positive correlation was noted between the Transfiguration type and the Approach Acceptance item (correlation coefficient 0.61) and between the Escape type of ITMQ and the Escape Acceptance item of DAP-R (correlation coefficient 0.46) (Table 5).

Table 5. Correlations between the ITM types and DAP-R dimensions

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed); *correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Responses to other items of the initial version of ITMQ

The majority (117, 79.6%) of participants agreed or strongly agreed that their suicidal behaviour was to solve a problem. A similar proportion (111, 75.5%) agreed or strongly agreed that they had tried other means to solve their problems but were unsuccessful. The majority (105, 71.4%) disagreed or strongly disagreed that a person who kills or harms herself would get sympathy from other people. A slightly smaller proportion (91, 61.9%) disagreed or strongly disagreed that it was important to them that people would be sympathetic or understanding of their attempts while almost a quarter of respondents (38, 25.9%) agreed or strongly agreed with that statement.

The relationship between the different types of ITMQ with demographic, clinical, religious views and concepts of death are presented in Table 6 (online supplement). Higher scores on the Flight type were found in those who said that they intended to die (t (133) = –2.97, p = 0.003) and those who were disappointed that they had not died (t (129) = 2.81, p = 0.006). Those who said that they were disappointed that they had not died had lower scores on the Appeal/Blackmail type (t (127) = –1.94, p = 0.05). The Ordeal/Game type was associated with drinking alcohol before the suicidal/self-harming act (t (130) = –2.12, p = 0.03). Female ratings of the Self-punishment type were significantly higher than in males (t (142) = –2.6, p = 0.01). Those who had four or more previous attempts of suicide or self-harm had higher ratings on the Self-punishment type compared with those who had only one previous attempt (p = 0.004). Higher ratings of the sacrifice type were associated significantly with not having children (t (135) = –2.03, p = 0.04). There was a significant association between religious views and the Transfiguration type (F = 4.59, p = 0.004). Post-hoc Tukey comparisons showed that atheists had lower scores than those who believe in God but not in organized religion (p = 0.02) and even lower than those who believe in organized religion (p = 0.003) but not than agnostics. The concept of death for patients showed a similar significant association with the Transfiguration type (F =5.43, p < 0.001). The difference occurred between those who believed that death was the end with no form of after-life and those who believed in a Judgement Day (p < 0.001) and those who believed in some form of existence after death (p = 0.03). The correlation between age and ITMQ types were very small and negligible. The correlations between the different types of ITMQ and number of children, number of dependent children and number of previous admissions did not reveal any significant findings.

Discussion

We have developed a self-report questionnaire (ITMQ) to measure the motives of suicidal and self-harming behaviour based on Baechler's typology (Baechler, Reference Baechler1979). We used reliability tests and factor analysis to examine this typology. The final version of the questionnaire contains only 25 items and can be completed in less than ten minutes. Patients found it easy to complete with no significant distress reported.

The results of this study support a core component of Baechler's theory which views suicide and self-harm as a solution to a problem as endorsed by about 80% of subjects. This could have an impact on any therapeutic work where the focus is to help the person to find alternative strategies of solving the problem.

Using factor analysis, we found evidence for Baechler's types included in our study. However, the Appeal and Blackmail types were combined in one type and the Ordeal and Game types were combined in another. The fusing together into one of the Appeal and the Blackmail types is not surprising. Baechler himself, who analysed the two types in one chapter, comments: ‘An appeal is not absolutely distinct from blackmail: in both cases, what is involved is risking one's life to obtain something’ (Baechler, Reference Baechler1979, p. 149). In Blackmail, this something is precise, whilst in Appeal it is more vague and general, in the nature of attention or more correctly affection (Baechler, Reference Baechler1979). This could suggest that at a clinical level these two motives are very closely related in that the need to get something specific from the behaviour is associated with the need for affection or attention in most cases. The moderate correlation of the Appeal/Blackmail type with the Vengeance type gives some support to Baechler's clustering of these three types as ‘Aggressive’ (Baechler, Reference Baechler1979). Similarly, the combination of the Ordeal and Game types in one type, something which was again expected by Baechler lends some support to Baechler's general heading of ‘Ludic’ which included both (Baechler, Reference Baechler1979, p. 203). Our findings did not lend support to the general Escapist or Oblative types constructed by Baechler.

The Transfiguration type is presented by only one item. There could be two reasons for this. First, the statements/items that we have developed to represent this type were not good enough to capture the essence of the central meaning of transfiguration (to attain a better state of existence), and merged with some of the other meanings. For example, the item ‘I hoped to join loved ones by killing myself’ is perhaps too closely linked to the grief type. Second, it may be that our clinical sample was not wide or varied enough to recognize some of the items that we have used to represent this type, for example, ‘I chose a moment of bliss or joy to kill/harm myself because I did not want to lose that feeling’. Although represented by only one item, we kept the Transfiguration type as the aim of the factor analysis was not data reduction, but rather exploring the latent dimensions in this multidimensional phenomenon which would aid understanding. In addition, we did not want to lose that meaning which is distinct from others and could have some clinical implications in assessment and intervention. Future work is needed to address this limitation. We excluded the Crime type because we have reservations about the construct in that the in order to motive has not been adequately identified. A similar criticism has been made by Aron in his forward to the English translation of Baechler's book, regarding the Grief type (Baechler, Reference Baechler1979, page XV).

The Flight type was the most predominant type. This was predicted to be the case by Baechler himself (Baechler, Reference Baechler1979, p. 203) and is supported by previous similar findings (Reynolds and Berman, Reference Reynolds and Berman1995). On the other hand, the Vengeance type was the least predominant, supporting the finding that hostile motives are less likely to be endorsed by the individual (Loughrey and Kerr, Reference Loughrey and Kerr1989). The correlations between the different types support Baechler's suggestion that very rarely would one find only one motive operating in any particular case.

The negative correlation of the Flight type with Death Avoidance together with its positive correlation with Neutral and Escape Acceptance might be explained as follows: in the flight type, life is seen as intolerable, so this might make death relatively attractive, and possibly thereby reducing death avoidance. When the motive is to influence other people, one would not expect fear of death to be reduced and this might explain the positive correlation between the Appeal/Blackmail types with fear of death.

The association between the Flight type and the intent to die was expected by Baechler and fits with the view that suicide is a form of escape (Baumeister, Reference Baumeister1990). Interpersonal motives such as Appeal and Blackmail seem to be associated with less desire to die, supporting previous similar findings (Hjelmeland et al., Reference Hjelmeland, Hawton, Nordvik, Bille-Brahe, De Leo and Fekete2002; Holden et al., Reference Holden, Kerr, Mendonca and Velamoor1998; May and Klonsky, Reference May and Klonsky2013). This was interpreted as an indication that the person still has some level of social connection (May and Klonsky, Reference May and Klonsky2013). The association between the Transfiguration type and the belief in religion and after-life seems obvious as the hope in moving to a better state of being necessitates the belief in the existence of such a state, even if in vague terms.

The possible explanation for an association between the Ordeal/Game type and drinking alcohol before the attempt is that the disinhibition caused by alcohol might make it easier for the individual to use such behaviour as a way of tempting fate or as a game; however, this still needs further exploration. The reason for the association between the Sacrifice type and not having children is not clear. One possible explanation is that not having children who rely on the person for care might make it easier for the individual to view himself/herself as a burden on others, who might not need that care, and that they will be better off without him/her.

The ITMQ is an addition to the current measures of motives for suicidal and self-harming behaviour. The sample came from different clinical settings. The questionnaire was administered within a relatively short period of time following the behaviour. The ITMQ explores specific types of motives, the in order to motives. Examining the in order to motives might have more therapeutic value in that these motives are the future oriented goals of the behaviour, which suggests a degree of freedom in action and choice, unlike the because of motives which have a more deterministic nature since they are the past factors that have preceded or influenced the behaviour. The ITMQ is based on what we think is sound theoretical work. This is consistent with calls of experts in this field for research to be grounded in theory (Lester, Reference Lester, Joiner and Rudd2000a). One of the possible reasons for the theoretical vacuum in suicidology (Joiner and Rudd, Reference Joiner and Rudd2000) is that the concentration on investigating risk and protective factors (Rogers, Reference Rogers2001) has led to the use of aggregated data (nomothetic approach), rather than what is unique about each individual case (idiographic approach). The idiographic approach allows ‘the observer to get below the surface’ (Reynolds and Berman, Reference Reynolds and Berman1995) which is necessary to understand a complex phenomenon like suicide or self-harm where the subjective meaning is central to understanding. However, such an approach needs to lend itself to the process of generalization in order to be useful in furthering knowledge and future research. We believe that the Ideal Type methodology (Weber, Reference Weber1949) used by Baechler fulfils both requirements. A second important aspect of the theoretical work behind this study is that it views suicide and self-harm as a means to an end (Fig. 1). Examination of risk factors (which come within the realm of the because of motives in the terminology of this study) might imply that the behaviour is an end or a result for which we have to find the causes. This approach does not help a lot in understanding the internal logic (including the in order to motive) of the behaviour for the actor. Understanding these motives could have an impact on the rationale and type of intervention as well as its impact on significant others and subsequently the chance of repetition (Bancroft et al., Reference Bancroft, Skrimshire and Simkin1976). It is possible that understanding these in order to motives (or the internal logic) might help in examining the risk factors in a new light.

Figure 1. Diagrammatic representation of the internal logic of the behaviour and its meaning using flight type as an example

This study has some limitations. We have not looked into whether the group of patients who agreed to participate are different in any significant ways from those who declined to participate. There is always some subjectivity in interpreting and labelling factor analysis results; however, items fitted well with the theoretically appropriate factor or type. The consistency of this factor structure needs further confirmatory analysis in a different sample. We did not identify diagnosis and how this might correlate with the various motives/types. This is mainly because diagnosis is not directly relevant to Baechler's theory. We accept, however, that this needs testing. Another limitation of this study is that we do not have data on those who might have committed suicide later to correlate with the different types. The ITMQ was based only on Baechler's theory and therefore did not include any other possible motives not covered by that theory. Baechler's typology is intended to deal with the full range of suicidal and self-harming behaviour, something which might be criticized from a mainstream viewpoint. The difficulties associated with the categorization of the behaviour are addressed in our Introduction. In addition, such categorization is based on the presence or absence of the intent to die. In this context, to die is seen as an end, rather than as a means to an end, as conceptualized by Baechler. The presence or absence (or more accurately the degree) of intent could be seen as secondary to the goal to be achieved by the behaviour (in order to motive). For example, in the Appeal/Blackmail type one would expect a lesser degree of intent than in Flight type as found in this study. Therefore, the assessment of risk could be informed by identifying that particular in order to motive.

The ITMQ could be used in research and clinical settings. It could be used by adding a higher level of analysis to the current levels and in identifying risk groups. It could help clinicians as a first step or as a guide for a more in-depth understanding of the behaviour and possibly guiding intervention. An intervention which is informed by Baechler's work would include a number of components to address the different aspects of the behaviour (Fig. 1). This includes manipulating or removing, if possible, the factors that have led to the perception of a problem; challenging that perception by exploring the facts of the problem and the way it was seen by the person, and by improving the person's problem-solving skills. In addition, another component would address the in order to motives, the domain of the ITMQ. This could be done by challenging the need to have that specific motive in the first place (for example, do you really need to get that affection? Do you really need to make that person angry?); by challenging the internal logic of the behaviour (is this means appropriate to that end or is it a successful means, for example: did you get the affection you wanted?) and by helping the person to discover that there are other means to achieve that end (for example: let's make a list of the things that you could do to achieve that goal). The whole process could improve the person's understanding and insight into his or her behaviour.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all participants. This study did not receive any funding.

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S135246581700042X

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.