Introduction

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (2001) defines small businesses as actively trading with 0–19 employees while medium-sized businesses are actively trading with 20–199 employees. It is widely acknowledged that only a small proportion of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) create the majority of new jobs (Henrekson & Johansson, Reference Henrekson and Johansson2010; Lopez-Garcia & Puente, Reference Lopez-Garcia and Puente2012; Mason & Brown, Reference Mason and Brown2013; Lee, Reference Lee and Chan2014). These are referred to as high growth firms (HGFs) and defined by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2010) as firms with 10 or more employees that generate employment growth of 20% or more for 3 consecutive years. Based on this definition, Anyadike-Danes, Bonner, Hart, and Mason (Reference Anyadike-Danes, Bonner, Hart and Mason2009) found that just 6% of all SMEs in the United Kingdom were HGFs, responsible for half of all new jobs between 2002 and 2008. Mason and Brown (Reference Mason and Brown2013) arrived at the same conclusion using a different data set with the same definition. Heimonen (Reference Heimonen2012) also reported that only 8% of a large sample of Finnish SMEs qualified as HGFs and suggested that access to public research and development funding would increase both the number and employment capacity of these firms. Stangler (Reference Stangler2010) analysed data from a special United States Census Bureau and established that HGFs, while representing only 1% of all US businesses, generated ~10% of all new jobs annually. Henrekson and Johansson (Reference Henrekson and Johansson2010: 240) also examined some 20 data sets on SMEs from a variety of sources and concluded that ‘a few rapidly growing firms generate a disproportionately large share of all new net jobs’.

Barringer, Jones, and Neubaum (Reference Barringer, Jones and Neubaum2005) explained that HGFs are almost exclusively SMEs, an assertion that contravenes Gibrat’s law (Reference Gibrat1931), which states that size of the firm is independent of its growth rate. Similarly, Acs, Parsons, and Spencer (Reference Acs, Parsons and Spencer2008) reported that HGFs that generate the highest employment growth have <19 employees. Adding to these findings, Shane (Reference Shane2008) noted that the vast majority of SME start-ups are little more than wage substitution businesses and only few of their founders are entrepreneurs who plan exceptional growth involving significant new jobs from the outset. The term entrepreneur is used to differentiate owners of HGFs from owners who prefer to keep their businesses small (Bamberger, Reference Bamberger1983; Carland, Hoy, Boulton, & Carland, Reference Caird1984; Kotey & Meredith, Reference Kotey and Meredith1997).

Following the above, several researchers have urged governments to develop policies that focus scarce resources on HGFs (Shane, Reference Shane2008; Lerner, Reference Lerner2010; Mason & Brown, Reference Mason and Brown2013; Lee, Reference Lee and Chan2014) although only few countries have policies that specifically foster such firms (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2010). This is because it is difficult to identify SMEs with high employment growth potential, especially before growth commencing. Predicting future performance at start-up is difficult (Finkel & Greising, Reference Finkel and Greising2010) since growth patterns are episodic and nonlinear (Garnse, Stam, & Hefferman, Reference Garnsey, Stam and Hefferman2006). Added to this is the lack of publicly available data that enable tracking of SMEs and their performance.

This article reviews the literature to: (a) take stock of progress to date on determinants of HGFs; (b) suggest measures to address shortcomings; and (c) develop a framework for identifying HGFs. This will allow governments to focus on them for job creation.

Method

Several databases and online research houses including Proquest and NESTA were searched for relevant peer-reviewed articles, specialist white papers and books. Key words used include: HGF, gazelles, entrepreneurship and entrepreneurs. These were combined with words such as personality characteristics, traits, values, risk-taking, strategies, management practices, management teams, ownership structure, marketing, employment growth and several others as they became identified as associated with HGFs or their owners. The literature is unanimous in referring to HGFs as entrepreneurial, as such this review focused on both the HGF and entrepreneurship literatures.

The a priori assumption that above average growth is measurable means that an HGF is an existing not a start-up firm. However, many of the entrepreneurial and management characteristics identified in the literature are common to both HGFs and successful start-ups (Barringer, Jones, & Neubaum, Reference Barringer, Jones and Neubaum2005) therefore start-ups and nascent entrepreneurs were included in the search. Furthermore, the literature is ambivalent about the meaning of SME performance, with undefined descriptors such as ‘success’, ‘high performance’ and ‘high growth’ (Simpson, Padmore, & Newman, Reference Simpson, Padmore and Newman2012) often used. Where possible in this review performance was equated with employment growth, following the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development definition of HGFs (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2010). Articles were restricted to those in journals ranked by the Australian Business Deans Council or the Excellence in Research for Australia for rigour in the research reviewed.

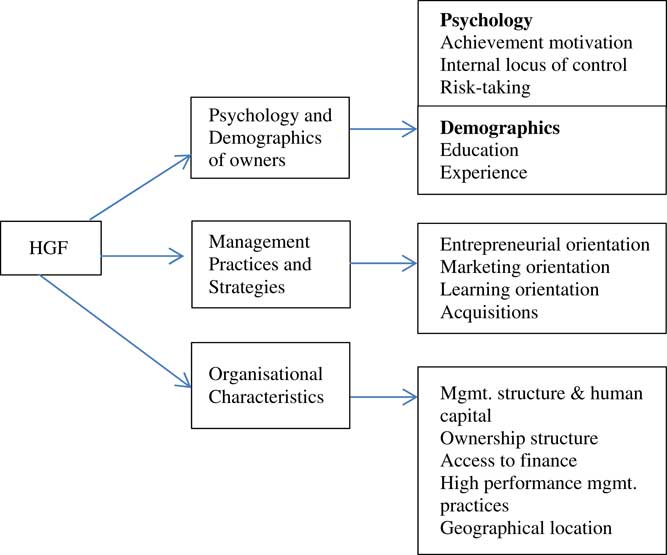

The literature review is framed around the three core components of small business growth, first identified by Storey (Reference Storey1994): (i) the psychology of the founder, (ii) the operating strategies and systems associated with growth and (iii) the characteristics of the organisation. Materials searched were organised into these three areas (see Figure 1) and by time frame to identify progression and shifts in the descriptors of HGFs and entrepreneurs over time.

Figure 1 Key markers of high growth firms

The ratings assigned to the various markers of HGFs in Table 1 were based on the literature review. Three academics and two practitioners were asked to rate the markers after reading the literature review and their ratings compared with those of the authors. The ratings assigned by the practitioners and academics were close to or consistent with those of the authors, confirming the relative importance of each marker for identifying HGFs.

Table 1 Summary and ratings of markers of HGFs

Note.

HGF=high growth firm; HPMP=high performance management practices.

Literature Review: Markers of HGFs

The literature credits 16th century French economist, Richard Cantillon as the first to attempt to define entrepreneurship, basically as self-employment (Ahmad & Seymour, Reference Ahmad and Seymour2008). In the 18th century, notable economists such as Adam Smith and Jean Baptiste Say added leadership and production to Cantillon’s definition. Joseph Schumpeter (Reference Schumpeter1934) penned his definition of entrepreneurs as innovators who implement change within markets, identifying five manifestations of change: introduction of new (or improved) goods, new methods of production, opening new markets, exploiting new sources of supply and re-engineering/organisation of the business.

Interest in entrepreneurs intensified over time, spanning several disciplines (economics, finance, sociology and psychology), after the above-named economists linked them to economic growth. The early economic descriptions were followed by an ardent but unsuccessful search for personality traits that separate entrepreneurs from the rest of society. Some of the most important traits are examined next.

Psychology of entrepreneurs

Early researchers in the area of entrepreneurial traits include Smith (Reference Spence and Essoussi1967) who announced a direct relationship between ‘the character of the man and the type of firm he builds and the growth of this firm’. Consistent with researchers before him Caird (Reference Cacciolatti and Fearne1993: 12) reported that successful entrepreneurs ‘exhibit high needs for achievement, autonomy, dominance and change, with low needs for deference, order, affiliation and abasement’. Several other researchers have confirmed these traits as associated with entrepreneurs (see e.g., Kotey & Meredith, Reference Kotey and Meredith1997; Rauch & Frese, Reference Rauch and Frese2007; Chell, Reference Chell2008; Brandstatter, Reference Brandstatter2011). Even so, the psychology literature appeared to have reached a consensus by the late 1980s that risk-taking, tolerance of ambiguity and internal locus of control are core entrepreneurial traits, with Gartner (Reference Gartner1989) suggesting that there was little left to research in this field. Nonetheless, Carland, Carland, and Pearce (Reference Carland, Carland and Pearce1995) cautioned that these personality traits are not exclusive to entrepreneurs but are found in leaders in other professions. Moreover, the enduring quality of these traits for entrepreneurs has been questioned. For example, the entrepreneur’s propensity to take risks is widely debated in the literature. Brockhaus (Reference Brockhaus1980) established that entrepreneurs have a moderate risk-taking propensity but qualified this finding, signalling that risk-taking behaviour could differ between established and nascent entrepreneurs. Using the Risk Scale of the Jackson Personality Inventory and a large sample, Carland, Carland, and Pearce (Reference Carland, Carland and Pearce1995) refuted Brockhaus’ finding, reporting that 115 ‘proven’ entrepreneurs from their sample of 848 business owners displayed significantly higher propensity for risk than their less entrepreneurial counterparts. However, Carland, Carland, and Pearce (Reference Carland, Carland and Pearce1995) did not define ‘proven entrepreneurs’ by size or growth of their operations so that it is unclear if they operated HGFs. Others have confirmed Brockhaus’ original doubts that owner–managers of well-established HGFs do have a lower propensity for risk (Miner & Raju, Reference Miner and Raju2004; Dalzeil, Reference Dalzeil2008). These more recent findings are in accord with the Friedman-Savage’s (Reference Friedman and Savage1948) utility function which proposed that entities in the upper tail of wealth distribution (established HGFs) are typically risk averse, while the more destitute in the lower tail (start-ups) display high risk-taking propensity to acquire wealth. Douglas (Reference Douglas2006: 2) agreed with Friedman and Savage (Reference Friedman and Savage1948), suggesting that the budding entrepreneur’s ‘psychic involvement in the process of becoming an entrepreneur … might be so important that he/she trades off risk reduction to become an entrepreneur sooner’. Clearly, trait profiling is far from an exact science when it comes to identifying the essential characteristics of entrepreneurs.

Following the failure to find a unique set of traits that differentiates entrepreneurs from the rest of society (Hisrich, Langan-Fox, & Grant, Reference Hisrich, Langan-Fox and Grant2007), the search for HGF markers was extended to behaviours of their owners, linking types of owners to their management practices or strategies and business outcomes (Bamberger, Reference Bamberger1983; Covin, Reference Covin and Slevin1991; Kotey & Meredith, Reference Kotey and Meredith1997; Chell, Reference Chell2008; Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin, & Frese, Reference Rauch, Wiklund, Lumpkin and Frese2009). In general, entrepreneurs have been associated with proactive strategies (referred to as entrepreneurial orientation), differentiating them from the more conservative and reactive strategies pursued by small business owners (Covin, Reference Covin and Slevin1991; Wiklund, Patzelt, & Shepherd, Reference Wiklund, Patzelt and Shepherd2009).

Over the same period, other researchers branched off to investigate the role of demographics in isolating HGFs from other SMEs. Gender was extensively examined, with many researchers reporting lower performance for female than male-owned businesses (Robb, Reference Robb2002; Watson, Reference Watson2002) while others found no differences (Du Reitz & Henrekson, Reference Du Reitz and Henrekson2000; Cron, Bruton, & Slocum, Reference Cron, Bruton and Slocum2006). This study recoils from the inconclusive gender debate to consider education and experience, over which the entrepreneur has control, as markers of HGFs.

Education and experience of entrepreneurs

Becker’s (Reference Becker1975) well-known human capital theory states that the knowledge, abilities and capabilities of entrepreneurs are key determinants of business success. Becker emphasised the educational component of human capital as critical to entrepreneurship. Others such as Watson, Steward, and BarNir (Reference Watson, Steward and BarNir2003) have claimed that the entrepreneurial skills of HGF owners improve with education while Barringer, Jones, and Neubaum (2005) and Hessels, van Gelderen, and Thurik (Reference Hessels and van Stel2008) reported that education differentiates fast growth from slow growth firms. College education in the technical field of the business adds to the entrepreneur’s expertise while general management training enhances skills in areas such as planning, foresight and creativity and helps build relevant social networks (Barringer, Jones, & Neubaum, 2005). These authors noted, however, that postgraduate education could have little impact on entrepreneurship. Lee and Chan (Reference Lee and Hsieh1998) suggested that tertiary degree holders were less likely than high school graduates to aspire to become entrepreneurs, a situation attributed to emphasis on risk aversion in the tertiary education curricula (Taatila, Reference Taatila2010). Calling for a different approach to teaching entrepreneurship, Kirby (Reference Kirby2004) has argued consistently that the traditional education system stultifies rather than develops the attributes and skills required for entrepreneurship.

Using a qualitative research approach and a small sample of high profile entrepreneurs, Jusoh, Babak, Aaimiran, and Kadir (Reference Jusoh, Babak, Aaimiran and Kadir2011) found that established entrepreneurs favoured training on specific business issues to creativity and innovation taught in classroom situations. A survey of small business owners in Australia revealed that only 16.6% had a Bachelor degree. The majority (54%) had completed secondary school and 67% had undertaken a vocational training course (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013). Although these statistics do not establish the educational qualifications of HGF owners they demonstrate that few business owners in Australia have tertiary qualifications.

Lafuente and Rabetino (Reference Lafuente and Rabetino2011) and Barringer, Jones, and Neubaum (2005) noted that past entrepreneurial experience, including failed ventures, consistently predicts future entrepreneurial performance. Past entrepreneurial experience provides relevant knowledge and the networks for accessing opportunities and resources for growth. Cassar (Reference Carlson, Upton and Seaman2014) found the entrepreneur’s industry and start-up experiences to be positively associated with accurate forecasting. An Australian study by Warren and Hutchinson (Reference Warren and Hutchinson2000) supported the contention that the founding entrepreneur’s technical and financial management experiences are important contributors to success of high-tech HGFs. It follows then, that while postgraduate qualifications are not critical to HGFs, college education, training in relevant skill areas, and management and entrepreneurial experiences contribute positively to building HGFs.

Cooper (Reference Cooper1998) posited that on their own the above psychological and demographic characteristics do not directly affect firm performance, but influence the management strategies and practices that shape the characteristics of the firm. Nonetheless, the owner–manager’s personality and demographics are important to any investigation into enterprise performance because they focus on the source of strategy, which ultimately determines performance. A review of the strategic orientation and management practices of entrepreneurs follows next.

Strategies of HGFs

Strategic orientation refers to the pattern within the collection of business-related activities that defines the competitive position of the firm within its industry or market (Covin, Reference Covin and Slevin1991; Olson, Slater, & Hult, Reference Olson, Slater and Hult2005). Laukkanen, Nagy, Hirvonen, Reijonen, and Pasanen (Reference Laukkanen, Nagy, Hirvonen, Reijonen and Pasanen2013) classified the strategic orientations of HGFs into: entrepreneurial orientated; marketing or brand orientated, including export orientation, especially selling through the internet; and learning orientated. Eggers, Kraus, Hughes, Laraway, and Snycerski (Reference Eggers, Kraus, Hughes, Laraway and Snycerski2013) added customer orientation. Consistent with the vast body of literature, Laukkanen et al. (Reference Laukkanen, Nagy, Hirvonen, Reijonen and Pasanen2013) found that an entrepreneurial orientation is critical to performance of HGFs. Entrepreneurial orientated strategies encompass innovativeness, risk-taking, proactiveness, autonomy and competitive aggressiveness (Miller, Reference Miller1983; Lumpkin & Dess, Reference Lumpkin and Dess1996; Covin & Wales, Reference Covin and Wales2011). The entrepreneur’s risk-taking propensity was discussed earlier and being proactive or taking initiative is embodied in innovation.

Entrepreneurial orientation

Schumpeter’s definition of innovation is largely relevant today, encompassing the introduction of a new or significantly improved good or service, operational process, organisational/managerial process or marketing method (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2012). Innovation may be radical, such as high-tech or ground-breaking inventions, or incremental, involving minor improvements or simple adjustments to existing products or processes (Drucker, Reference Drucker1985; Dewar & Dutton, Reference Dewar and Dutton1986; Bhaskaran, Reference Bhaskaran2006). Amason, Schrader, and Thompson (Reference Amason, Shrader and Thompson2006) and Oke, Burke, and Myers (Reference Oke, Burke and Myers2007) all noted that the majority of HGFs improve or refine their products, focusing on incremental rather than radical innovation. Referring to well-known product adaptions such as Ryanair and Microsoft, both of which grew beyond SMEs, Burke (Reference Burke2009: 33) stated that the most successful entrepreneurs are not masters of innovation, rule breakers or courageous risk takers, but are strategically ‘adept at making existing business models or markets perform better’. In effect, one of the most successful HGF strategies is solving the last 10% of the problem. Burke (Reference Burke2009) explained that successful entrepreneurs de-risk by using a lean start-up strategy involving adaptations of market-tested strategies and products so that scarce financial resources are not burnt up on new ideas that are not feasible. In the United Kingdom, O’Regan, Ghobadian, and Gallear (Reference O’Regan, Ghobadian and Gallear2006) found that high growth manufacturing firms competed largely on price, carried out limited research and development, but in terms of entrepreneurial innovation they were prospectors, continually searching for new market opportunities by upgrading products to meet market needs.

Navarro, Casillas, and Barringer (Reference Navarro, Casillas and Barringer2012) identified four different combinations of effective growth strategies implemented by HGFs:

-

1. A domestic expansion strategy through the acquisition of new clients plus product enhancement and innovation of new products.

-

2. A product enhancement strategy to attract new clients linked with international sales expansion.

-

3. A simple generic domestic expansion using acquisition of new clients to grow sales.

-

4. A sophisticated combination of new product innovation or improving existing products with a dedication to international expansion.

From a sample of 89 established HGFs, each with consistent high growth over at least 5 years, Navarro, Casillas, and Barringer (Reference Navarro, Casillas and Barringer2012) provided strong support for strategies 1, 2 and 4 but not the generic market penetration strategy in 3. Examining SME growth strategies over a 10-year period, Leitner and Guldenberg (Reference Leitner and Guldenberg2010) reported that strategies involving change are more effective for stimulating growth than persistent commitment to a Porter (Reference Porter1980) generic strategy. In effect, innovation is critical to HGFs although innovation does not have to be radical and usually occurs incrementally.

Customer, marketing, export orientation

The literature persistently shows a strong association between entrepreneurship and marketing (Morris & Lewis, Reference Morris and Lewis1995; Webb, Ireland, Hitt, Kistruck, & Tihanyi, Reference Webb, Ireland, Hitt, Kistruck and Tihanyi2011). Marketing in this respect extends beyond reactive response to customer complaints to proactive activities that deliver high customer value and satisfaction (Eggers et al., Reference Eggers, Kraus, Hughes, Laraway and Snycerski2013). It requires effective generation and use of market intelligence (Baker & Sinkula, Reference Baker and Sinkula1999). Cacciolatti and Fearne (Reference Cassell, Nadin, Gray and Clegg2013) argued that growth and sustainable advantage depends on the ability to acquire, analyse and use market intelligence. Market intelligence provides key market knowledge that feeds the firm’s ability to develop innovative solutions to existing and future customer needs (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Ireland, Hitt, Kistruck and Tihanyi2011).

Among the four Ps of marketing promotional strategy, often expressed in brand building, has the most entrepreneurial effect and is a frequently cited contributor to SME growth (Centeno, Hart, & Dinnie, Reference Centeno, Hart and Dinnie2013). Branding links the internal business culture, behaviour and communication with its external business image. Rode and Vallaster (Reference Rode and Vallaster2005) and Spence and Essoussi (Reference Smith2008) have portrayed brand identity as a powerful product differentiating strategy for highly competitive markets. Timmons (Reference Timmons1999) claimed that SMEs that do not establish a brand identity early in their life cycle are likely to disappear from the market place. Centeno, Hart, and Dinnie (Reference Centeno, Hart and Dinnie2013) noted that in general SME branding is carried out with minimum planning, limited resources and characterised by trial and error. Rode and Vallaster (Reference Rode and Vallaster2005: 125) concluded from a qualitative study of SMEs in their early lifecycle stages that, with one notable exception, the cases in their sample were ‘unable to clearly articulate their core business, their values and their marketing position’. Many of Rode and Vallaster’s (Reference Rode and Vallaster2005) respondents viewed branding as an indulgence and a black hole for scarce financial resources. The exception was an HGF whose entrepreneurial founders demonstrated not only the ability to project the core values of their internal culture into a corporate brand, but also to ‘painstakingly acquire, analyse and utilise marketing intelligence’ (Rode and Vallaster, Reference Rode and Vallaster2005: 126). The literature clearly demonstrates that strong brand identity and effective use of market intelligence are key markers of a HGF.

Several studies have documented the positive effect of exports on SME growth (Harm, Reference Harms2009; Golovko & Valenti, Reference Golovko and Valentini2011; Hessels & van Stel, Reference Hessels, van Gelderen and Thurik2011), in particular, selling through the internet (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2014). Firms that sell in international markets are able to access a customer base many times larger than their domestic market and if the internet is used, cost is significantly reduced. Export orientation is a widespread characteristic of HGFs (Harm, Reference Harms2009). Golovko and Valenti (Reference Golovko and Valentini2011) contended that export orientation and innovation reinforce each other in a dynamic virtuous circle while Hessels and van Stel (Reference Hessels, van Gelderen and Thurik2011) concluded that strong export orientation has high positive impact on SME and economic growth. They recommended using export orientation as a selection criterion for SME financial assistance.

Learning orientation: Skilling the workforce

According to Sinkula, Baker, and Noordewier (Reference Sinkula, Baker and Noordewier1997: 309) learning orientation refers to the ‘set of organizational values that influence the propensity of the firm to create and use knowledge’. Learning orientated SMEs are better equipped to respond effectively to dynamic environments (Wolff, Pett, & Ring, Reference Wolff, Pett and Ring2015). Learning can occur at the individual and/or organisational level, but individual learning does not automatically translate to organisational learning unless actions are taken to link the two. A firm will lose individual knowledge when employees leave if it does not have the organisational processes to capture that knowledge.

Much of the literature concerns formal individual learning, and supports the hypothesis that high individual learning enhances organisational performance (Mitra, Reference Mitra2000; Carlson, Upton, & Seaman, Reference Carland, Hoy, Boulton and Carland2006; Rhee, Park, & Lee, Reference Rhee, Park and Lee2010). In a survey of family-owned SMEs, Carlson, Upton, and Seaman (Reference Carland, Hoy, Boulton and Carland2006) found poorly trained employees to constitute a significant barrier to growth. They also reported that learning in entrepreneurial firms often occurs on-the-job and through mistakes.

Jayawarna, Macpherson, and Wilson (Reference Jayawarna, Macpherson and Wilson2007) differentiated generic from targeted training and described generic training as generalised and informal. They contended that SMEs are predisposed to generic training because it is cheap but confirmed that formal training targeted at specific business needs, as distinct from generic training, correlates positively with performance. Coetzer, Battisti, Jurado, and Massey (Reference Cooper, Gimeno-Gascon, Javier and Woo2011) also found that SME managers avoid external generic training programs and are concerned about the poor availability of formal training that addresses their specific day-to-day needs. They called on policy makers to address the gap in learning and development of owner–managers of growth orientated SMEs. The literature therefore clearly supports targeted training at the organisational level as important characteristics of HGFs.

Extending the learning theory, Uhlaner, Van Stel, Duplat, and Zhou (Reference Uhlaner, Van Stel, Duplat and Zhou2012) noted that outsourcing and alliances with large established partners enable small firms to increase sales revenue through access to well-resourced innovation processes, industry networks and wider markets.

Growth by acquisition

Entrepreneurial research has traditionally focused on organic growth, although policy makers believe that industry rationalisation by acquisition yields economies of scale that strengthen the competitive performance of the industry as a whole (Annis, Merefield, & Schine, Reference Annis, Merefield and Schine2009). Delmar, Davidson, and Gartner (Reference Delmar, Davidson and Gartner2003) noted that 10% of Swedish HGFs grew by acquisition. Gilbert, McDougall, and Audretsch (Reference Gilbert, McDougall and Audretsch2006) argued that growth by acquisition offers significant advantages to SMEs including: instant access to new markets without the related expenditure, the flow on effects of the acquisition’s reputation, elimination of a competitor, reduced fixed overheads through economies of scale, supply discounts from high volume purchases and the ability to influence market pricing through oligopoly or monopoly power. Although the mainstream business press suggests that mergers create redundancies, Gilbert, McDougall, and Audretsch (Reference Gilbert, McDougall and Audretsch2006) argued that a HGF may revitalise a large but moribund competitor by injecting fresh organisational knowledge to overcome preacquisition rigidities and inertia and generate employment growth. The sparse literature on strategy and extent of SME growth by acquisition, presents a fertile area for future research.

Organisational characteristics of HGFs

Organisational characteristics identified in the literature as differentiating the small number of HGFs from the plethora of lower performing SMEs include: human capital, corporate structure and use of resources including finance and external advice (Gilbert, McDougall, & Audretsch, Reference Gilbert, McDougall and Audretsch2006; Lee & Hsieh, Reference Lee2010; Eggers et al., Reference Eggers, Kraus, Hughes, Laraway and Snycerski2013; Lee, Reference Lee and Chan2014). These factors are discussed in the next section, organised into management structure and human capital, and access to and use of resources.

Management structure and human capital

Research unequivocally supports the position that knowledge capital, skills and creative capabilities of the firm’s human element are positively related to competitive advantage and growth (Harms, Reference Harms2009; Lee & Hsieh, Reference Lee2010; Lafuente & Rabetino, Reference Lafuente and Rabetino2011; Eggers et al., Reference Eggers, Kraus, Hughes, Laraway and Snycerski2013). This means an effective management structure is critical to HGF performance (O’Regan, Ghobadia, & Gallear, Reference O’Regan, Ghobadian and Gallear2006). Flowing from this is the contention that team-managed SMEs deliver more enduring competitive advantage than individually managed SMEs (Weinzimmer, Reference Weinzimmer1997; Birley & Stockley, Reference Birley and Stockley2000; Lafuente & Rabetino, Reference Lafuente and Rabetino2011), although this position is refuted by others. Pasanen and Laukkanen (Reference Pasanen and Laukkanen2006) analysed 63 team-managed and 45 individually managed SMEs and found virtually no differences in performance or strategic choices between the two management structures. Nonetheless, to the extent that HGF owners do not have all the skills necessary to operate and grow their businesses, it is pertinent that they access the missing skills to close the gap. Consequently, the effect of the single-tier leadership of the entrepreneur on the firm’s resources and capabilities may be leveraged by a management team or an informal board of directors for high employment growth (Ruef, Aldrich, & Carter, Reference Ruef, Aldrich and Carter2003; Lafuente & Rabetino, Reference Lafuente and Rabetino2011).

Dimov and Sheppard (Reference Dimov and Shepard2005) suggested that entrepreneurs themselves are likely, initially at least, to possess only technical knowledge related to their firm and would move to fill gaps in their knowledge capital by outsourcing and/or recruiting managers. Coad, Daunfelt, Johansson, and Wennberg (Reference Coad, Daunfelt, Johansson and Wennberg2014) also found that early in their evolution, HGFs are prone to head hunt scarce human capital from other firms. Hayton (Reference Hayton2003), Carlson, Upton, and Seaman (Reference Carland, Hoy, Boulton and Carland2006) and Wennberg (Reference Wiesner, McDonald and Banham2009) reported that HGFs widely use methodically planned recruitment practices designed to attract and retain high performing managers and executives. These include: written job descriptions, generous incentive-based compensation, formal and regular employee reviews and pay for work-related technical training. According to Hayton (Reference Hayton2003), the assumption that it is possible to identify all the managerial skills and behaviours required to support a continually changing strategic orientation ex-ante fails as soon as the environment changes, as it does in small HGFs. As a result, HGF owners prefer to hire managers able to adapt to the changing trends (Haydon, Reference Hayton2003).

Closely aligned with management structures is the issue of ownership structure – that is whether or not members of the management team should have ownership interest in HGFs. Lappalainen and Niskanen (Reference Lappalainen and Niskanen2012) reported a direct association between ownership structure and SME performance. Agency theory suggests that conflicts of interest may arise from separation or misalignment of managers and owners interests. McMahon (Reference Mazzarol2007) found a significant positive relationship between the level of equity held by SME managers and growth of their firm. Other researchers have shown that successful SMEs, especially family-owned firms, have concentrated ownership structures where ownership and management interests are well aligned (Nelson, Brunetto, Farr-Wharton, & Ramsay, Reference Nelson, Brunetto, Farr-Wharton and Ramsay2007; Lappalainen & Niskanen, Reference Lappalainen and Niskanen2012). Carlson, Upton, and Seaman (2006) established that high revenue growth firms use significantly more cash incentives to align owners and management goals than average performing firms. A good management team backed by appropriate reward structures is clearly a prerequisite for high growth.

Access to and use of resources

Cooper, Gimeno-Gascon, Javier, and Woo (Reference Coetzer, Battisti, Jurado and Massey1994) explained that HGFs benefit from high levels of capitalisation that allow their owners time to successfully implement their strategic objectives, develop ambitious strategies or change their course of action. Gilbert, McDougall, and Audretsch (Reference Gilbert, McDougall and Audretsch2006) supported this position, arguing the importance of adequate financial resources to employment and revenue growth. Their argument is weakened, however, by research showing low levels of entrepreneurial activities in environments with munificent resources (Covin & Slevin, Reference Covin1989; Agarwal & Chatterjee, Reference Agarwal and Chatterjee2007). It appears then, that it is the ability to achieve maximum productivity from scarce financial resources without compromising quality that differentiates HGFs from other small businesses.

Capital resources apart, Cassia and Minola (Reference Cassar2012: 1355) explained that hyper-growth SMEs have the ability to exploit ‘extraordinary business opportunities’ through ‘extraordinary access to resources (especially knowledge based)’. Coad et al. (Reference Coad, Daunfelt, Johansson and Wennberg2014) established that hiring practices of HGFs for workers at the operational level are radically different from the recruitment methods used for executives. They noted that HGFs in the knowledge intensive sector were likely to employ ‘young people, poorly educated workers, immigrants and individuals who experienced longer unemployment periods’, (p. 294) and improve their performance through in-house training. This strategy points to efficient as well as effective use of resources. Careful recruitment of the best accessible human capital at the top echelons is balanced with low cost human capital that can be moulded to the needs of the business at the lower levels of the firm.

In effect, while access to networks for accessing opportunities and resources is relevant to HGFs, it is the management of the resources for maximum productivity that generates enduring competitive advantage. Management practices of HGFs are discussed next.

High performance management practices (HPMPs)

A large body of literature analyses the impact of HPMPs on large organisations, but literature linking HPMPs to SMEs is difficult to find. Cassell, Nadin, Gray, and Clegg (Reference Cassia and Minola2002) noted that HPMPs are low on the priority list of small firms and encouraged them to learn these practices from large firms to benefit from the positive outcomes. Gadenne and Sharma (Reference Gadenne and Sharma2009) reported that SMEs adopting the six key elements of total quality management improved their overall performance in terms of employment and return on investment but concluded that compared with large organisations SMEs are slow to adopt such management tools. In contrast, Wiesner, McDonald, and Banham (Reference Wennberg2007) found strong evidence that HPMPs are more prevalent in medium-sized firms than in small firms. According to the authors, the most common HPMPs implemented by SMEs include quality circles, work teams, total quality management, cross training, employee committees, selective staffing, compensation incentives and information sharing. They concluded though, that these practices have not been widely adopted by high growth Australian medium-sized firms.

The literature suggests that HPMPs are not markers of HGFs. To the extent that these practices require formal and structured approaches, they may introduce rigidities that reduce the flexibility required in management processes of HGFs to respond to changes in their environment. A case study by Rompho (Reference Rompho2011) concluded that even simple HPMPs such as balanced scorecard, usually fail in SMEs because of frequent changes in strategy.

Geographical location

Gilbert, McDougall, and Audretsch (Reference Gilbert, McDougall and Audretsch2006) asserted that locating in clusters such as Silicon Valley is advantageous for access to capital but cautioned that other such locations may be disadvantageous because of competition for local resources, especially human capital. Simpson, Padmore, and Newman (Reference Simpson, Padmore and Newman2012) posited that no industry or business environment is predisposed to gestate HGFs and concluded that successful SMEs operate in dynamic and diverse (heterogeneous) environments. This means HGFs in the same industry will adopt strategies that align with their specific environments and that these strategies may differ in some respects from those adopted by similar firms in different locations.

Discussion and Conclusions

The study examined the extent to which the academic community has advanced the task of identifying markers of HGFs. The review shows general consensus around a number of markers, while others are disputed and a third group has not been adequately investigated. The markers are summarised in Table 1 and each rated on a 1 to 5 scale with 1 being of lowest significance and 5 highest for identifying HGFs.

It is generally agreed that owners of HGFs (entrepreneurs) are achievement orientated and have internal locus of control, traits shared with professionals and other high achievers in society. Early researchers described entrepreneurs as moderate risk takers, but others have found that their risk-taking propensity changes with the stage of the business. Aggressive pursuit of opportunities in the early stages requires entrepreneurs to be ‘calculated’ risk takers. However, during the mature stages of the business, they become risk averse seeking to protect, manage and build on what has been achieved. Moreover, instruments developed to identify entrepreneurs by their personality traits have not been effective and traits have so far had limited value to policy makers seeking to identify and support nascent HGFs. The presence of an entrepreneurial achievement motivation and/or strong locus of control scores a low rating of 1 as a marker of HGFs. Although personality traits identified as entrepreneurial can generally be deduced and confirmed from the strategies and management practices observed, such traits are not exclusive to owners of HGFs.

There is some consensus that college education, particularly in the technical areas of the business, provides the skills, knowledge and networks relevant to operating HGFs. In contrast, postgraduate management education appears to have limited value and may even deter entrepreneurship because of its emphasis on risk aversion. Entrepreneurs seek training in specific areas to address gaps in their knowledge and skills. These findings imply that rather than broad-based programs such as MBAs for entrepreneurs, tertiary institutions will be better served by working with industry associations to develop specific training programs that address skills and knowledge gaps for industry members, including entrepreneurs. Tertiary education is clearly not a prerequisite for a successful HGF, except where it forms the basis of professional qualifications required to enter the industry. However, overall qualifications including training undertaken to fill gaps in skills and knowledge of the entrepreneur are seen as important to success. Thus, education is rated 3, while the portfolio of knowledge acquired from various sources is rated 5.

Entrepreneurial and management experiences are recognised as critical to success of HGFs. They provide the networks that enable access to resources and opportunities and entrepreneurs learn more readily from experience that from classroom teaching. This means training or education programs that enable would-be entrepreneurs to experience the entrepreneurial process, for example, working alongside mentors, will be highly relevant to their development. The experience of failure also adds to the entrepreneurial process, calling for national cultures that tolerate failures and support innovation. Both entrepreneurial and management experiences are rated 5 as markers of HGFs.

With respect to strategies, there is agreement that an entrepreneurial orientation involving innovation is necessary for high growth. Entrepreneurs are not usually inventors or first movers but seek to add value through proactive search for opportunities, improvements and market exploitation. Given the central position of customers to business success, customer orientation is critical but must extend beyond reacting to complaints to proactive efforts at adding value to the benefits provided customers. To this end, product branding and promotion are necessary while internationalisation, particularly using the powers of the internet, opens new markets for HGFs. It is generally agreed that owners of HGFs pursue learning through targeted management and employee training to update knowledge in areas relevant to the business. Growth can also occur through acquisition, although this area is not well-researched. Entrepreneurial, marketing and learning orientations are necessary for HGFs to succeed, therefore these strategic orientations are each rated 5. Acquisition is one of many pathways to growth and not a critical predictor of HGFs.

Management teams provide clear indication of growth orientation but do not differentiate HGFs from other firms, except perhaps where managers are also owners, enabling close alignment of management and ownership interests. The entrepreneur can also address skills gaps through strategic outsourcing, informal board of directors or by collaborating with larger firms. These strategies are particularly useful at the nascent stage where resources are scarce but flexibility is needed to navigate uncertainties and shape the core idea. The literature is unanimous in its claim that HGFs address gaps in the owner’s knowledge by recruiting managers with complementary skills and knowledge or using outside expertise. In contrast, HGFs do not necessarily hire the best talents on the labour market for positions at lower levels of operation, but recruit employees with the potential to learn and adapt to their work situations. Access to the skills and knowledge needed for day-to-day operations as well as successful implementation of strategies are clearly essential and are rated 5, whether employed in-house or outsourced.

HPMPs are not visible in HGFs, especially at the nascent stages where they may interfere with the flexibility to respond to the dynamic environment but they could benefit firms at the bigger end of the size scale. HPMPs are rated 3; they can be beneficial but not critical to growth.

There is no clear consensus on the location characteristics of HGFs, therefore it is given a rating of 2. Access to finance and other resources are essential for growth, although an abundance of resources may lead to complacency that retards success. It is the ability to maximise productivity of scarce resources, including finance, without compromising quality that differentiates HGFs from other businesses. In spite of the caution, access to finance and other resources is rated 5.

Individually, the above markers do not denote an HGF; rather it is the weighted amalgam of all the markers that differentiate HGFs from the rest of the population of SMEs.

In general, while academia has not yet reached the point of producing a ‘tick the box’ template for positive identification of HGF (Hisrich, Langan-Fox, & Grant, Reference Hisrich, Langan-Fox and Grant2007) we present a different view to the assertion that comparatively little is presently known about the essential characteristics of HGFs (Wiklund, Patzelt, & Shepherd, Reference Wiklund, Patzelt and Shepherd2009). However, we agree with Mason and Brown (Reference Mason and Brown2013) that HGFs are not a homogenous group. Nonetheless, there is sufficient evidence to indicate that entrepreneurs can be identified by what they do or intend to do, that is, their demonstrated innovative experiences and skills give credibility to their projected entrepreneurial strategies. This credence tends to be validated in the content and presentation of their business plans while dampening scepticism that they lack the management skills to deliver. Clearly, this broad appraisal constitutes the first set of criteria for assessing the growth potential of nascent HGFs. Baum and Locke (Reference Baum and Locke2004) and Finkel and Greising (Reference Finkel and Greising2010) noted that seasoned venture capitalists with $100 of millions at stake get it right for about one out of four investments using these criteria. Part of the difficulty is that early growth patterns of HGFs are nonlinear and episodic (Garnsey, Stam, & Hefferman, Reference Garnsey, Stam and Hefferman2006). It is also impossible to accurately predict all the elements of the external environment that would impact on the business at start-up. However, as Storey (Reference Storey1994) noted, once the business enters a profitable commercial phase, the accuracy of forecasting performance improves. This is consistent with equity providers’ preference for established over nascent businesses. Since a significant percentage of the management literature revolves around identifying the factors that affect performance of organisations, including businesses of various sizes, the quest for predictors of HGFs will continue. Nonetheless, it is important to consider how the process can be improved. Consequently, some of the barriers to the process are discussed next.

A major barrier to the quest for markers of HGFs is the reluctance among researchers to cross disciplinary boundaries to assemble the plethora of predictor variables into a holistic model of growth determinants for testing. This is due to differences in methodologies and research norms across disciplines. A focus on what entrepreneurs do rather than who they are places the problem in the business and management discipline and minimises conflicts with other disciplines. Another problem is the absence of clear and generally accepted definitions of an entrepreneur and performance thresholds recognised as high growth. In particular, the widespread reference to enterprise success in the literature makes performance an elusive concept. While productivity and revenue appear more dominant in the literature than employment growth as measures of performance, performance measures based on employee numbers do not capture nascent firms with growth potential, making such firms difficult to identify. Moreover, the small numbers of HGFs means they are difficult to locate among the vast number of SMEs, a situation that renders the task of compiling statistically significant samples of HGFs almost impossible. Further, data on HGFs are not published or available in the public domain, as occurs for listed companies. In Australia, the taxation office collects performance data on all entities each year. Associated organisations such as the Australia Bureau of Statistics can access and analyse data from the Australian taxation office to identify high performing from low performing SMEs and their characteristics. A national definition of HGFs is advocated, consistent with definitions of firm sizes. This would encourage widespread adoption of the definition and uniform measurement of HGFs.

It is the amalgam of the tangible and intangible processes leading to growth that need to be explained through a holistic cause and effect framework. However, preference for quantitative methodologies in business disciplines poses problems for examining the plethora of determinants with small samples. While Leitch, Hill, and Neergaard (Reference Leitch, Hill and Neergaard2010: 252) advocated expanding the ‘hegemony of the traditional approach to entrepreneurship … by non-positivist research concerned with the investigation of social reality’ to advance the quest for a ‘Comprehensive Theory’, Hisrich, Langan-Fox, and Grant (Reference Hisrich, Langan-Fox and Grant2007: 575) called on psychology researchers to ‘develop theories of entrepreneurship, and undertake empirical research’, criticising the dearth of empirical work on the intangible entrepreneurial factors they saw as pivotal to economic growth. This lack of consensus on appropriate methodology poses an unnecessary barrier to understanding the determinants of high growth. We propose a mixed approach involving quantitative analysis of national longitudinal data sets to identify characteristics of HGFs. The findings from such analysis can be enriched by case studies or other qualitative methods to capture characteristics not evident in the quantitative data.

Much of the literature also appears to lack relevance, for example experiments with university students are not the same as drawing experience from real business people (Mazzarol, Reference Mazzarol2012) and have limited direct relevance to policy makers intent on fostering employment growth. Attempts to devise screening instruments for nascent entrepreneurs such as by Carland, Carland, and Pearce (Reference Carland, Carland and Pearce1995) and Brockhaus (Reference Brockhaus1980) never evolved into practical tools of value to policy makers. The cumulative problems of identifying HGFs have led some researchers to suggest that the quest for a growth template is ‘unrealistic or at least premature, since growth is a multi-dimensional, heterogeneous and complex phenomenon’ (Leitch, Hill, & Neergaard, Reference Leitch, Hill and Neergaard2010: 250). We argue that significant progress has already been achieved in this area and that persisting with relevant methodologies will deliver a template even if it is not a prefect predictor. We propose a study based on our framework with data from national longitudinal data sets such as from the Australian Bureau of Statistics sourced from the Australian taxation office.

As noted above some of the traditional variables predicting HGFs have been weakened by recent counter arguments. They include risk tolerance, access to large amounts of capital and the enduring nature of entrepreneurship. Recent research contradicts the ‘traditional’ consensus of the vast body of entrepreneurial literature which holds that entrepreneurial firms remain entrepreneurial from their embryonic to mature stages. Drucker (Reference Drucker1985) noted that entrepreneurship is only a stage in the evolution of an enduring enterprise.

Clearly, more than five decades of intense academic research has achieved significant progress in identifying the amalgam of basic elements that differentiate HGFs from the bulk of SMEs. The difficulty is prioritising and sequencing them into a model that facilitates identification of nascent HGFs. This paper makes a contribution in this respect. We suggest the use of mixed methods to assess the extent to which the various markers predict HGFs and at which lifecycle stages the markers apply.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers whose constructive feedback enabled us to improve the original article.