INTRODUCTION

Turnover can be harmful to organizational performance (Glebbeek & Bax, Reference Glebbeek and Bax2004) and replacement costs are often very high (Hinkin & Tracey, Reference Hinkin and Tracey2000). Retention of talented workers is a priority for HR professionals and organizations (Buckingham & Vosburgh, Reference Buckingham and Vosburgh2001; PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2004). Different meta-analyses have reported that turnover intention is the strongest predictor of actual turnover (Steel & Ovalle, Reference Steel and Ovale1984; Tet & Meyer, Reference Tett and Meyer1993; Griffeth, Hom, & Gaertner, Reference Griffeth, Hom and Gaertner2000). It is thus crucial to better understand the underlying causes of turnover intentions.

Meyer and Allen (Reference Meyer and Allen1991) conceptualized a model presenting three components of organizational commitment: (1) affective (emotional attachment and identification with the organization); (2) continuance (awareness of the costs associated with leaving the organization); and (3) normative (feeling of obligation to continue employment with the organization). The authors suggest that the commonality between these three components of commitment is ‘the view that commitment is a psychological state that (a) characterizes the employee’s relationship with the organization, and (b) has implications for the decision to continue or discontinue membership in the organization’ (Meyer & Allen, Reference Meyer and Allen1991). Organizational commitment has been identified as a predictor of turnover intentions (Hackett, Lapierre, & Hausdorf, Reference Hackett, Lapierre and Hausdorf2001; Bentein, Vandenberg, Vandenberghe, & Stinglhamber, Reference Bentein, Vanderberg, Vanderberghe and Stinglhamber2005; Wagner, Reference Wagner2007).

Spector (Reference Spector1997) stipulates that job satisfaction can be considered either as an overall feeling about the job or as a related set of attitudes about different facets of the job. Research has proven that unsatisfied employees leave their jobs more often than satisfied employees (Martin, Reference Martin1990; Hellman, Reference Hellman1997).

‘Employees don’t quit their companies, they quit their boss’ is a popular adage that has been proven empirically. In their chapter reviewing turnover and retention research, Holtom, Mitchell, Lee, and Eberly (Reference Holtom, Mitchell, Lee and Eberly2008) suggest, among other things, that future research focus on developing models that capture the importance of interpersonal ties.

So far, turnover models have focused either on job satisfaction and organizational commitment or on leader effect, independently and mostly through correlational models. These studies yield sometimes conflicting results and lead researchers to argue that there has been a paucity of research on turnover intentions (McCarthy, Tyrrell, & Lehane, Reference McCarthy, Tyrrell and Lehane2007). To our knowledge, only one study has attempted to present a turnover model including leadership, job satisfaction and organizational commitment through structural equation modeling (SEM; Williams & Hazer, Reference Williams and Hazer1986). These authors suggest that turnover studies failing to include both job satisfaction and organizational commitment and the causal relation between these two variables should be viewed cautiously (Williams & Hazer, Reference Williams and Hazer1986). However, subsequent research on turnover seems to have ignored this recommendation.

Research has been conducted to identify how leadership behaviors can be used to encourage employees to achieve better organizational outcomes (Locke, Reference Locke2000). However, very few studies have tried to better understand the impact of leadership behaviors on organizational predictors of turnover (such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment and intention to quit job).

To address this gap in the literature, this study proposes a model including supervisory behavior, job satisfaction and organizational commitment in explaining turnover intentions. We wish to emphasize the role of supervisory behavior in the turnover model by differentiating people-oriented and task-oriented supervisory skills in a model using all of the variables included in Williams and Hazer’s model. We argue that Williams and Hazer’s recommendations to include both job satisfaction and organizational commitment are to be taken seriously when conducting research on turnover intentions. We believe that supervisory behavior will have an effect on turnover intentions through its impact on job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Furthermore, we argue that, when including both job satisfaction and organizational commitment in a turnover model and considering the interaction between all three of these variables, the effect of job satisfaction on turnover intentions will occur through its effect on organizational commitment. Finally, we believe that this model will apply to both small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and large enterprises.

THEORETICAL CONTEXT

Turnover is a concept that has been studied from three main perspectives. The first perspective is based on turnover models, wherein turnover is viewed as a consequence of employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The second perspective is based on the leadership literature and leader–member exchange theory (LMX), whereas the third is based on organizational support theory. The next section presents these three perspectives.

Turnover models: The role of job satisfaction and organizational commitment

In the present study, turnover is regarded as a termination from the employees’ side without any involvement or pressure from the employer’s side. With regards to employee turnover, Tett and Meyer (Reference Tett and Meyer1993) were among the first to report that job satisfaction and organizational commitment contribute independently to the prediction of turnover intentions/cognitions. Later on, following a meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover, Griffeth, Hom, and Gaertner (Reference Griffeth, Hom and Gaertner2000) concluded that organizational commitment predicted turnover better than job satisfaction.

Some researchers present the view that organizational commitment develops through job satisfaction and that organizational commitment mediates the influence of job satisfaction on turnover intentions (Price & Mueller, Reference Price and Mueller1986; Williams & Hazer, Reference Williams and Hazer1986). Other authors have stated the reverse relation; namely that organizational commitment precedes job satisfaction (Bateman & Strasser, Reference Bateman and Strasser1884). However this view has not been supported by later research (Williams & Hazer, Reference Williams and Hazer1986). In fact, in their meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates and consequences of organizational commitment, Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, and Topolnytsky (Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002) have entered job satisfaction as a correlate (rather than an antecedent) of commitment in their model explaining turnover and turnover intentions. Aside from Williams and Hazer (Reference Williams and Hazer1986) who used SEM, the other studies used correlational models and regressions that could not attest for the simultaneous influence of job satisfaction and organizational commitment on turnover intention.

Joseph, Ng, Koh, and Soon (Reference Joseph, Ng, Koh and Soon2007) presented a meta-analytic SEM of turnover of information technology professionals but despite the fact that organizational commitment was highly correlated to turnover intentions, it was removed from the model to minimize multicollinearity since it was highly correlated with job satisfaction. Furthermore, this model did not take into account the influence of leadership behaviors that literature has identified as being associated with turnover (Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vanderberghe, Sucharski, & Rhoades, Reference Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vanderberghe, Sucharski and Rhoades2002; Kammeyer-Mueller & Wandberg, Reference Kammeyer-Mueller and Wanberg2003; Maertz, Griffeth, Campbell, & Allen, Reference Maertz, Griffeth, Campbell and Allen2007).

Impact of leadership on employees and employee behaviors

‘Leadership solves the problem of how to organize collective effort; consequently, it is the key to organizational effectiveness’ (Hogan & Kaiser, Reference Hogan and Kaiser2005: 169). Hogan and Warrenfeltz (Reference Hogan and Warrenfeltz2003) present a domain model of leadership that identifies four classes of managerial competencies: (1) intrapersonal skills (able to control emotions and behavior, internalized standards of performance); (2) interpersonal skills (building and maintaining relationships, social skill role-taking and role-playing, impression management, political savoir-faire); (3) business skills (abilities and technical knowledge needed to plan, budget, coordinate and monitor organizational activities); and (4) leadership skills (influence and team-building skills). This model presents the different broad competencies that are to be expected of leaders.

In a study on the relationship between supervisor behavior and employees’ mood, Miner, Glomb, and Hulin (Reference Miner, Glomb and Hulin2005) found that employees rated their interactions with their supervisor as 80% positive and 20% negative. However, the 20% negative interactions affected the employees’ mood five times more than the positive interactions. In his article on the role of the supervisor in creating a healthy workplace, Gilbreath (Reference Gilbreath2004) states: ‘Although not yet recognized in the management literature, it is clear that positive supervision is fundamental component of a psychologically healthy work climate.’ Gilbreath and Benson (Reference Gilbreath and Benson2004), in their study on the contribution of supervisor behavior to employee psychological well-being, come to the following conclusion ‘We believe that there is now ample justification for those concerned with psychosocial working conditions to consider supervisor behavior as a potentially influential variable.’ Bono, Foldes, Vinson, and Muros (Reference Bono, Foldes, Vinson and Muros2007) reported that employees with supervisors high on transformational leadership experienced more positive emotions throughout the workday and were less likely to experience decreased job satisfaction, than were those with supervisors low on transformational leadership (Bono et al., Reference Bono, Foldes, Vinson and Muros2007).

Studies on the impact of leadership behavior on employee attitudes prove to be conclusive. Abusive supervision (hostile verbal and non-verbal behaviors) has been found to be related to lower levels of job satisfaction, normative and affective commitment and increased psychological distress (Tepper, Reference Tepper2000). Bligh, Kohles, Pearce, Justin, and Stovall (Reference Bligh, Kohles, Pearce, Justin and Stovall2007) report that perceptions of aversive leadership are positively related to employees’ resistance and negatively related to employees’ job satisfaction. A study by Rad and Yarmohammadian (Reference Rad and Yarmohammadian2006) has established that there was a significant correlation between leadership style and employees’ job satisfaction. Furthermore, these authors have found that the most positive relation to employee satisfaction was between employee-oriented dimensions of leadership as opposed to task-oriented leadership behaviors. Williams and Hazer (Reference Williams and Hazer1986) have found a stronger influence on organizational commitment when looking at consideration leadership style rather than task-oriented leadership style. A study by Vandenberghe, Bentein, and Stinglhamber (Reference Vandenberghe, Bentein and Stinglhamber2004) found that affective commitment to the supervisor predicted affective commitment to the organization, which, in turn, predicted intention to quit, which predicted actual turnover. In their study on guanxi, defined as a close relationship based on mutual benefit between supervisor and employee, Cheung, Wu, Chan, and Wong (Reference Cheung, Wu, Chan and Wong2009) found that job satisfaction fully mediated the effects of supervisor-subordinate guanxi on intention to leave but partially mediated the relationship between supervisor-subordinate guanxi and organizational commitment.

In their chapter reviewing turnover and retention research, Holtom et al. (Reference Holtom, Mitchell, Lee and Eberly2008) suggest, among other things, that future research focus on developing models that capture the importance of interpersonal ties. By studying the impact of the perception of the supervisor task-related and interpersonal skills on employees’ job satisfaction, organizational commitment and intention to quit, we believe that this study is in line with their recommendations.

As applied in leadership research, LMX refers to the dyadic exchange that is developed between leaders and their followers (Graen and Uhl-Bien, Reference Graen and Mary Uhl-Bien1995). LMX has been associated with performance (De Coninck, Reference De Coninck2011), job satisfaction (Epitropaki and Martin, Reference Epitropaki and Martin2005) and organizational commitment (Schriesheim, Castro, & Cogliser, Reference Schriesheim, Castro and Cogliser1999; Martin, Thomas, Charles, Epitropaki, & McNamara, Reference Martin, Thomas, Charles, Epitropaki and McNamara2005). Bauer, Erdogan and Wayne (Reference Bauer, Erdogan, Liden and Wayne2006) found that LMX predicted actual turnover in their sample of executives. These studies did not account for the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment in predicting turnover intentions. In fact, a meta-analysis of LMX has found a significant relationship between LMX satisfaction, commitment and turnover intentions (Gerstner & Day, Reference Gerstner and Day1997). Again, the relationship between the latter variables was, however, not considered in the previous meta-analysis. Similarly, a study by Kim and Carlson (Reference Kim, Lee and Carlson2010) reports a U-Shape curvilinear relationship between LMX and turnover intentions but this model did not include job satisfaction or organizational commitment, which could perhaps account for part of the variance and explain the found effect. A study by Han and Jekel (Reference Han and Jekel2011) reports that job satisfaction seems to mediate the link between LMX and turnover intentions among nurses. The latter model did not include organizational commitment though.

Organizational support theory

Organizational support theory (Eisenberger, Cummings, Armeli, & Lynch, Reference Eisenberger, Cummings, Armeli and Lynch1997; Rhoades & Eisenberger, Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002) relates to the global belief employees develop concerning the extent to which the organization values their contributions and cares about their well-being. In a meta-analysis on perceived organizational support (POS), Rhoades and Eisenberger (Reference Rhoades and Eisenberger2002) have found that POS was related to job satisfaction, affective commitment, performance and fewer withdrawal behaviors in employees. Interestingly, research has indicated that perceived supervisor support (PSS) seems to increase POS, which, in return, increases both the sense of responsibility in employees to contribute and help the organization and the level of affective commitment to the organization, reducing turnover (Eisenberger, Armeli, Rexwinkel, & Lynch, Reference Eisenberger, Armeli, Rexwinkel and Lynch2001). Eisenberger et al. have conducted a series of three studies measuring the contribution of PSS to POS and employee retention, and they have come to the following conclusion: ‘Supervisors, to the extent that they are identified with the organization, contribute to perceived organizational support, and, ultimately, to job retention’ (Reference Eisenberger, Stinglhamber, Vanderberghe, Sucharski and Rhoades2002: 572). In a subsequent study, Maertz et al. (Reference Maertz, Griffeth, Campbell and Allen2007) reported that PSS had independent effects on turnover cognitions not mediated through POS. Moreover, they have found that low PSS strengthened the negative relationship between POS and turnover, while high PSS weakened it. These results take into account the relationship between supervisor and employee in terms of PSS but do not include in the model other variables susceptible to explain turnover intentions. Nevertheless, the results from LMX and PSS stress the importance of considering leadership in turnover intention models.

Research model and hypotheses

Looking at the effects of supervisory behavior, Vandenberghe, Bentein, and Stinglhamber (Reference Vandenberghe, Bentein and Stinglhamber2004) found that employees’ affective commitment to their supervisor predicted their affective commitment to the organization, which in turn predicted their intention to quit. Another study by Rad and Yarmohammadian (Reference Rad and Yarmohammadian2006) established that there was a significant relationship between leadership style and employees’ job satisfaction. Furthermore, these authors found that employee-oriented dimensions of leadership influenced job satisfaction significantly more than task-oriented leadership behaviors. Both LMX and transformational leadership take into account the relationship between the supervisor and his/her employees; we believe that this may explain why studies on employee-oriented supervisory behavior find similar associations with employee attitudes such as job satisfaction.

Williams and Hazer (Reference Williams and Hazer1986) found a stronger influence on organizational commitment when looking at consideration leadership style rather than task-oriented leadership style. Using path analysis, the previous authors found that leaders’ consideration had an impact on organizational commitment through job satisfaction. Furthermore, they found that the only direct link to turnover intentions was with organizational commitment. These authors concluded that personal and organizational characteristics influence organizational commitment only through job satisfaction.

We have built the present study’s model on the three perspectives presented above: (1) turnover is viewed as a consequence of employees’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment; (2) based on the leadership literature and LMX; and (3) based on organizational support theory. We thus propose an integrative model of turnover intentions including supervisory behavior, job satisfaction and organizational commitment. The aims of the present study are to test whether we find the same relationships as Williams and Hazer (Reference Williams and Hazer1986) have found, adding leadership style (people-oriented vs. task-oriented styles) to the model. Furthermore, we test whether our model is valid in both large enterprises and in SMEs. Research on employee turnover has largely been conducted in large enterprises. In fact, the only study on employee turnover intentions in SMEs we have found was conducted in Africa and tested the influence of employee perception of organizational politics and equity on organizational commitment and turnover intention (Chinomona & Chinomona, Reference Chinomona and Chinomona2013). Therefore, our study is innovative in two ways: first, it is the first study to test a turnover model including supervisory behavior, job satisfaction and organizational commitment in SMEs and second, it is, to our knowledge, the first study to compare a turnover model results tested within both an SME and large enterprise samples.

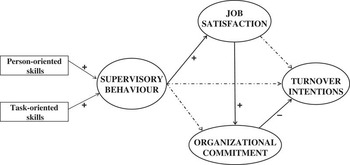

Given the study’s aims, and the preceding theoretical and empirical background, we thus propose to test the following research model, as presented in Figure 1. This model implies three research hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Supervisory behavior is positively and significantly related to job satisfaction, not to organizational commitment or to turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 2: Supervisory behavior is positively and significantly related to organizational commitment through job satisfaction.

Hypothesis 3: Supervisory behavior predicts turnover intentions only indirectly, through job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Figure 1 Research model

METHODS

Procedure and participants

This study was part of a larger project on HR practices and retention for which the second author has received approval from his university’s ethics committee. The Canadian organizations participating in the project allowed their employees to answer a survey questionnaire (∼30 min) during work hours. These organizations operate both in the private (manufacturing, retailing and services) and public sectors (health and social services). In total, 763 individuals thus participated in the study by completing the questionnaire. More than half of these individuals (58%) work for SMEs, i.e., firms with <250 employees), 37% work for large enterprises and 5% are employed by public organizations. Half of the participants (48%) were women with a mean age of 33.86 (from 17 to 64, median=31).Twenty-eight percent (14.3%) of the participants had less than a college degree, 3.1% had completed a college degree and 39.5% had a university degree (mostly a bachelor degree) and 1.2% of the participants have answered ‘other’ for education level. Close to half of the participants (46%) had at least one person at their charge. For work-related characteristics, the mean yearly salary was about $34,000 (27.1% earned <$20,000 while 9.5% earned more than $70,000). One out of four participants was holding a white-collar job (25.5%). The mean seniority at job was 8.9 years (median=5 years). Finally, 41% declared being union members, two-thirds of our sample (67.1%) worked in an organization from the private sector and one quarter of the participants (26.4%) considered their job to be a temporary position.

Measures

Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction was measured using a short version of the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (Weiss, Dawis, England, & Lofquist, Reference Weiss, Dawis, England and Logquist1967). This repeatedly validated instrument includes 12 statements to measure ‘intrinsic’ job satisfaction (α=0.87), six items to measure ‘extrinsic’ job satisfaction (α=0.81) and two items measuring general job satisfaction, which we did not include in this study. The 18 items are rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale (1=‘very low satisfaction’ and 6=‘very high level of satisfaction’).

Organizational commitment

Organizational commitment has been measured using a modified version of Meyer, Allen, and Smith’s (Reference Meyer, Allen and Smith1993) affective and normative commitment scales. As conceptualized by Meyer and Allen (Reference Meyer and Allen1991), organizational commitment is composed of three dimensions, namely affective, normative and continuance. Affective commitment refers to the individual’s level of identification with the organization (Porter, Steers, Mowday, & Boulian, Reference Porter, Steers, Mowday and Boulian1974), normative commitment refers to a sense of moral obligation that incites the individual to stay in the organization (Wiener, Reference Wiener1982), whereas continuance commitment – quite different in nature than the other two – refers to the perceived costs (e.g., pension fund) of an eventual departure from the organization (Becker, Reference Becker1960). Now, following Meyer et al. (Reference Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch and Topolnytsky2002: 41), affective commitment and normative commitment are found overall to be better predictors of the employee turnover rate than continuance commitment, whose measurement would benefit from more refinement. Moreover, HRM practices do not seem to have a significant impact upon continuance commitment (Meyer & Smith, Reference Meyer and Smith2000). The affective (α=0.93) and normative dimensions (α=0.86) were each measured by six statements to which respondents were asked their level of agreement on a 6-point Likert scale (1=‘totally disagree,’ 6=‘totally agree’).

Turnover intentions

The intention to quit was measured using two statements from Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins, and Klesh’s (Reference Cammann, Fichman, Jenkins and Klesh1983) Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire. The two statements were assessed with a 6-point Likert scale. The first statement reads: ‘How often do you happen to ponder leaving your current job?’ while the second statement reads: ‘What are the probabilities that you will be looking for a new job within the next year?’

Supervisory Behavior

Supervisory behavior was measured using 8 items from a previously developed leadership measure (Geringer, Frayne, & Milliman, Reference Geringer, Frayne and Milliman.2002). The participants were asked to evaluate each of the eight statements pertaining to their supervisor’s leadership behaviors (presence or absence of each behavior). An exploratory factor analysis was conducted, identifying two dimensions underlying supervisory behavior (see Table 1). Thereby, the first dimension includes five statements related to the supervisor’s person-oriented skills (α=0.768). This dimension explained 39% of the total variance before a varimax rotation and 34% after rotation. The second dimension includes three statements related to task-oriented skills (α=0.616). This dimension explained 18% of variance before rotation and 23% after rotation. As this last measure contains a small number of items, its Cronbach’s α value tends to underestimate reliability because the ‘tau-equivalence’ assumption is violated (Graham, Reference Graham2006). Furthermore, the fact that each of the three items correlated highly with the measure’s total score (r=0.77, 0.76 and 0.73) suggests that none should be discarded (Tavakol & Dennick, Reference Tavakol and Dennick2011).

Table 1 Exploratory factor analysis of the supervisory behavior measure (n=763)

As presented in Figure 1, the supervisory behavior construct is modeled here to be ‘formative’ rather than ‘reflective,’ given its composite and multidimensional nature (Roberts & Thatcher, Reference Robert and Thatcher2009). Such a construct is composed of many indicators that each captures a different aspect; hence, changes in these indicators bring or ‘cause’ change in their underlying construct (MacKenzie, Podsakoff, & Jarvis, Reference MacKenzie, Podsakoff and Jarvis2005).

Although some researchers consider common method bias to be an overstated problem (Brannick, Chan, Conway, Lance, & Spector, Reference Brannick, Chan, Conway, Lance and Spector2010), basic precautions should still be taken to minimize the potential risks (Conway & Lance, Reference Conway and Lance2010). Thus, the questionnaire was designed to be anonymous, giving the respondents all the latitude needed to express their true perceptions, attitudes and intentions. Robust measurement scales were used, with the independent and dependent variables being placed in different sections of the questionnaire. Different question formats were used for each set of variables, that is, for SB, JS, OC and TI. The fact that these constructs are clearly distinct both conceptually and in terms of their underlying factors also contributes to reduce the risk attributable to common method variance (Brannick et al., Reference Brannick, Chan, Conway, Lance and Spector2010). Additionally, we used the latent method factor approach recommended by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, and Podsakoff (Reference Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee and Podsakoff2003: 894) to further examine this issue. We thus conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) with a covariance-based SEM approach in which an unmeasured latent method construct was added to the measurement model, the eight measures being allowed to load on this construct as well as on their theoretical construct. This CFA, whose results are presented in Table 2, allowed us to break down the variance of the measures into theoretical, random error and method components (Williams, Cote, & Buckley, Reference Williams, Cote and Buckley1989). The results showed that 63% of the average variance was explained by the four theoretical constructs, 35% by random errors and only 2% by the method construct. Moreover, this model did not fit the data as well as a second CFA model in which the latent method construct was removed, further suggesting that common method bias is not a major threat in this study.

Table 2 Results of the CFA with unmeasured latent method construct (ULMC)

Notes. Model fit indices: χ2/df=23.7, NFI=0.88, GFI=0.93, CFI=0.88, RMR=0.207, RMSEA=0.173.

CFA=confirmatory factor analysis.

RESULTS

SEM was used to assess the research model, using Bentler and Weeks’ (Reference Bentler and Weeks1980) approach as implemented in the EQS computer program (Byrne, Reference Byrne2006). The factorial structure of the measurement model was first tested by conducting a CFA of the posited tetra-factorial structure, and comparing the results of this analysis to those of a second CFA that posited a mono-factorial structure instead. As presented in Table 3, the research model’s four-factor structure fitted the data much better than the alternative one-factor structure, thus providing initial validation of the measurement model.

Table 3 Results of the four-factor and one-factor CFAs of the research constructs (n=763)

Notes. Four-factor model fit indices: χ2/df=8.3, NFI=0.95, GFI=0.96, CFI=0.96, RMR=0.038, RMSEA=0.098.

One-factor model fit indices: χ2/df=26.6, NFI=0.79, GFI=0.84, CFI=0.80, RMR=0.129, RMSEA=0.183.

CFA=confirmatory factor analysis.

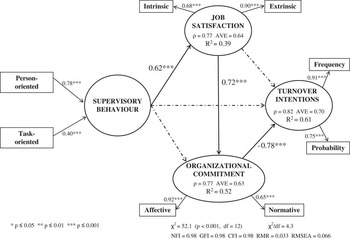

The unidimensionality, reliability and convergent validity are assessed by examining the level of fit of the research model and the estimated loadings that link the different dimensions to their respective constructs. As shown in Figure 2, values of 4.3 for the normed χ2, 0.98 for the CFI, 0.03 for the RMR and 0.07 for the RMSEA indicate adequate overall fit with no evidence of model overfitting. Note also that internal and external consistency criteria for all dimensions of the constructs, be it in terms of unidimensionality, reliability or convergent validity, attain levels of adequacy similar to the ones attained in prior assessments of construct validity. The reliability and convergent validity of the reflective constructs was supported by the values obtained for the ρ and average variance extracted coefficients, respectively. The size and significance of the path coefficients linking the different constructs to their respective dimensions provide evidence of convergent validity.

Figure 2 Results of testing the research model (n=763).

For the formative construct, namely supervisory behavior, the usual reliability and validity criteria do not apply as one must first verify that there is no multicollinearity among the indicators that form such a construct (Petter, Straub, & Rai, Reference Petter, Straub and Rai2007). This is verified with the variance inflation factor (VIF), the guideline being that this statistics should not be greater than 3.3 for any formative indicator (Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, Reference Diamantopoulos and Siguaw2006)Footnote 1 . Here, a VIF value of 1.17 for both indicators satisfies this criterion. Formative indicator validity is then confirmed by a weight (γ) that is significant, in the right causal direction, and not <0.10. Again this proved to be true for both formative indicators with respective weight values of 0.78 (p<.001) and 0.40 (p<.001).

Given the presence of multiple constructs in the research model, discriminant validity must be assessed, that is, assessing the extent to which the constructs as measured are unique from each other. Here, the shared variance between a reflective construct and other constructs must be less than the average variance extracted by a construct from its measures (Fornell & Larcker, Reference Fornell and Larcker1981). Table 4 shows this to be the case for all three reflective constructs in the research model, that is, JS, OC and TI. For the lone formative construct, SB, the fact that it shares <50% variance with any other construct (inter-construct correlation inferior to 0.70) is evidence of discriminant validity (MacKenzie, Podsakoff, & Jarvis, Reference MacKenzie, Podsakoff and Jarvis2005).

Table 4 Discriminant validity and inter-correlations of the research constructs (n=763)

Notes. The AVE is inappropriate for formative constructs.

Sub-diagonals: correlation=(shared variance)1/2.

a Diagonal: (AVE)1/2=(Σλ i 2/n)1/2.

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

Added validity can be provided by comparing the research model to an alternative ‘full effects’ model, that is, by positing added direct relationships between supervisory behavior and organizational commitment, supervisory behavior and turnover intentions, and job satisfaction and turnover intentions, and then rerunning the SEM analysis. As shown in Table 5, this last model explains 3% less variance in turnover intentions (R 2=0.58 vs. 0.61) and shows less fit (χ2/df=5.5 vs. 4.3, RMSEA=0.077 vs. 0.066). Moreover, the path coefficients for the three added relationships are quasi-null and non-significant, strongly suggesting that this alternative model is to be rejected in favor of the more parsimonious research model.

Table 5 Alternate model test results

Note. ***p<.001.

We also reran the SEM analysis by adding control variables: age, education level, gender, salary and unionization. The results of this second analysis indicate that adding these control variables as determinants of job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intention provide no significant increases in explained variance and yielded a worse model fit when compared with the model without control variables.

Finally, we ran separate SEM analyses on two sub-samples, that is, the large enterprises (N LE=280) and the SMEs (N SME=444). As shown in Table 5, results for the two sub-samples in terms of path coefficients and model fit indices were similar to those for the full sample, thus providing added validity to the research model. Note that this last analysis is worthwhile to the extent that few studies have attempted to understanding turnover intentions in the specific context of SMEs. However, these last results may simply indicate that the size of the organization has no moderating effect on the influence of supervisory behavior upon turnover intentions.

DISCUSSION

The main objective of this paper was to test the influence of supervisory behavior on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in a turnover model. Furthermore, we proposed to use a large sample of workers from different types of organizations to test our general model and then test the model separating our sample according to the size of the organizations (SMEs and large organizations).

Overall, our results support a similar model proposed by Williams and Hazer (Reference Williams and Hazer1986) that job satisfaction does not have a direct significant predictive effect on turnover intentions. Rather, job satisfaction seems to predict organizational commitment which, in turn, negatively predicts turnover intentions. Our model seems to support the view that commitment mediates the relationship between job satisfaction and turnover intentions (Price & Mueller, Reference Price and Mueller1986). This finding seems to replicate what Griffeth, Hom, and Gaertner (Reference Griffeth, Hom and Gaertner2000) found in their meta-analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover, namely that organizational commitment predicted turnover better than job satisfaction.

Furthermore, we wished to add to the model a measure of supervisory behavior that distinguished between task-oriented and people-oriented skills. It seems that person-oriented supervisory behaviors contributed to the model more than task-related skills. These results are similar to the ones reported by Rad and Yarmohammadian (Reference Rad and Yarmohammadian2006), indicating that the most positive relation to employee satisfaction was between employee-oriented dimensions of leadership as opposed to task-oriented leadership behaviors. Other research have found similar effect of positive supervisory behavior (Williams & Hazer, Reference Williams and Hazer1986; Kim, Reference Kim2002). Moreover, it seems that supervisory behavior has a direct effect only on job satisfaction, it does not predict directly the level of organizational commitment or turnover intentions. It is thus crucial that future research on turnover intentions that wish to study the role of leadership behavior take into account the mediating role of job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The instrument used to measure leadership was built by our research team and presented eight leadership behaviors. Although this instrument yielded acceptable psychometric properties, it would be interesting in future research to use a validated instrument measuring leadership styles. Another limit relates to the use of self-administered questionnaires (e.g., risk of common method bias). Measuring all variables through a self-administered questionnaire may pose a risk of common method variance and lead to an overestimation of the relationships between attitudinal and behavioral constructs. Our model supports the view that turnover models need to include both job satisfaction and organizational commitment and that turnover models should take into account the mediating effect of organizational commitment in predicting the impact of job satisfaction on turnover intentions. We agree with Williams and Hazer (Reference Williams and Hazer1986: 230) that ignoring the relationship between job satisfaction and organizational commitment represents a ‘serious limitation’ and that turnover models that fail to include both job satisfaction and organizational commitment ‘should be viewed cautiously.’ In spite of these recommendations, research since Williams and Hazer’s 1986 study have failed to replicate the model or to take into account their recommendations. We believe that in light of the fact that we have replicated their results 25 years later, future research should take their recommendations seriously.

Furthermore, leadership seems to be a significant variable in our turnover model, especially person-oriented behavior dimension. Future research should address the role of leadership whether testing LMX theory of POS or even destructive leadership in relation to job satisfaction, organizational commitment and turnover intentions. So far, research on leadership and turnover intentions has failed to include all of these variables in one model. Leadership styles could also be tested and added to the model, such as Bass and Avolio’s transformational, transactional and ‘laissez-faire’ leadership styles (Bass & Avolio, Reference Bass and Avolio2004).

CONTRIBUTION TO RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

Our results indicated that job satisfaction influenced turnover intentions through organizational commitment. Many organizations have put forward programs to increase job satisfaction, for instance, by giving away bonuses or good compensation benefits packages in an effort to retain their best talents. However, our model seems to indicate that, contrary to job satisfaction, organizational commitment has a direct effect on turnover intentions. We thus suggest that organizations put efforts into sharing and promoting their organizational values with their employees. This strategy could increase employees’ sense of belonging to the organization and thereby decreasing their intention to leave. We think that the latter would help keep their best talent within the organization.

The fact that our study stresses the important role of interpersonal leadership on turnover variables, emphasizes the importance for the professionals in charge of selection and promotion to understand the underlying abilities related to good interpersonal leadership skills. In fact, in order to fully understand leadership, Hogan and Hogan (Reference Hogan and Hogan2001) stress the importance of taking into consideration the concept of personality. We think that, in order to better understand leadership, we first need to better understand underlying mechanisms of leadership behaviors, one such mechanism being personality profiles.

Furthermore, we believe that our results indicate the importance, when hiring or promoting managers, to take into account their interpersonal skills as well as their task-oriented skills as employees from both SMEs and large organizations have indicated that these personal skills weigh more importantly on employees’ attitudes and turnover intentions. In terms of leadership style, research has identified that high transformational leadership in supervisors is associated with higher job satisfaction and positive emotions in employees (Bono et al., Reference Bono, Foldes, Vinson and Muros2007). The difference between transformational leadership and its counterpart (transactional leadership) is, in part, the fact that transformational leaders are person-oriented as well as task-oriented. While many higher management selection processes are mostly based on task-related performance, we believe that it is at least equally important for managers to score high on interpersonal (people-oriented skills). While some of these skills could be developed through coaching programs or training, it would be best to stress their importance in a selection or promotion context in order to ensure that the candidates possess them before they find themselves in a managerial position. Finally, because people-oriented leadership skills seem to have a significant impact on employees’ job satisfaction, we believe that it is important to integrate people-oriented skills in manager’s annual performance appraisals.

Conclusion

The goal of the present study was to test a model including supervisory behavior, job satisfaction and organizational commitment in explaining turnover intentions. To our knowledge, this is the first study to measure the impact of leadership on all of these variables included within the same structural model. Our results stress the importance of including leadership behaviors in turnover models and the strong impact of person-oriented dimension of leadership as opposed to task-oriented dimension in predicting turnover intentions. Furthermore, this study emphasizes the importance of measuring the mediating role of organizational commitment in predicting the impact of job satisfaction on turnover intentions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their valuable suggestions that greatly contributed to improving the final version of the manuscript. The authors would like to thank the Canada Research Chairs Program and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for their financial support of this research.