The strong performance of populist radical right (PRR)Footnote 1 parties in recent elections has caused considerable turmoil across Western democracies’ deeply rooted party systems. Despite this overall increase in PRR voting and exclusionary attitudes, however, within-country variation in receptiveness to the reactionary rhetoric and policies that the PRR advocates is striking (Golder Reference Golder2016). Specifically, these parties are often and increasingly stronger in areas seemingly detached from the effects of immigration, globalization and transnationalism, the key issues they politicize.

A key example is France’s PRR party Le Rassemblement National (RN),Footnote 2 which in recent elections has made its largest gains and grown most rapidly in rural and peri-urban areas (Gombin Reference Gombin2015; Guilluy Reference Guilluy2016). In many ways, these areas are far removed from RN’s early strongholds in the more ethnically diverse, economically strained urban areas (Gombin Reference Gombin2015; Mayer Reference Mayer and Barker1992) and deindustrialized “rust belt” regions stricken by global trade shocks (e.g., Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Frieden Reference Frieden2018; Gest Reference Gest2016) or “persistent poverty” (Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose2018) usually identified as fertile ground for these parties. Yet, as I show, large and increasing numbers of citizens in these relatively quaint, homogeneous areas confront a different, localized set of challenges related to postindustrialization and structural change: the growing concentration of services and economic opportunities in and around larger urban agglomerations. First, this concentration has generated considerable spatial inequalities in access to such services and opportunities. Second, the high costs of housing have put areas where they are concentrated out of reach for many individuals, while making declining areas difficult to leave. For these reasons, large numbers of individuals have become residentially constrained, thus possessing a limited capacity to respond to these developments.

Take a local resident, who interrupted a town hall meeting held in March 2018 in a picturesque, rural village in southwestern France. “We are in prison here!” he shouted, explaining how the lack of local opportunities, services, and public transport made cars and long daily commutes a painful, unwanted reality.Footnote 3 A mayor of a comparable nearby locality voiced a similar concern about the injustices faced by citizens in the area: “There is a strong sense of powerlessness here. Instead of investing in jobs and services, which are leaving these areas—it is really hard to maintain them—we see billions of euros going to immigrants, social housing and the ‘banlieues’Footnote 4 of big cities. People have been paying their social security contributions, their taxes, and now feel like the state is spending them on immigrants rather than their social welfare.”Footnote 5

Taking these spatial inequalities as my point of departure, I articulate a theory of residential constraints to deepen understanding of subnational variation in contemporary PRR support. Despite growing interest in geographic divides in (radical) political behavior and exclusionary attitudes (Frieden Reference Frieden2018; Maxwell Reference Maxwell2019; McNamara Reference McNamara2017); regional inequalities and the deprivation underlying them (e.g., Adler and Ansell Reference Adler and Ansell2019; Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Frieden Reference Frieden2018; Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose2018); and place-based identity and consciousness as important determinants of electoral choices and PRR backlash (Cramer Reference Cramer2016; Fitzgerald Reference Fitzgerald2018; Lee, Morris, and Kemeny Reference Lee, Morris and Kemeny2018), scholars have thus far paid little attention to the powerful role that residential constraints play in shaping such place-based considerations or individuals’ responses to regional inequalities. Accordingly, I hypothesize that PRR parties are particularly successful in areas where access to economic opportunities and services is compromised and among residentially constrained individuals whose capacity to respond to this lack of access is limited. Residential constraints thus generate a set of relative economic grievances and render them highly salient in localities that may otherwise appear unaffected by more objective hardships.

In a globalized, postindustrial context that both demands increasing degrees of mobility and flexibility and incentivizes individuals to (re-)locate closer to larger urban agglomerations, the growing concentration of services and opportunities has rendered prosperous areas where they are abundant out of reach for many individuals (Inchauste et al. Reference Inchauste, Karver, Kim and Jelil2018; Le Galès and Pierson Reference Le Galès and Pierson2019). It has also made it difficult to leave areas that are on the losing end of this equation. Indeed, the high and growing costs of housing in prosperous areas, a lack of affordable options, and decreasing property values in declining regions cause many individuals to feel “stuck” in places where these resources are increasingly scarce. Residential constraints and the resulting incapacity to respond to spatial inequalities, I argue, thus play a key role in influencing receptiveness to PRR parties’ rhetoric about “ordinary” populations who are “left behind” or “ignored.” Understood as such, they provide a lens through which PRR parties politicize, and local residents interpret, broader demographic and economic societal change.

To make this case, I use a multimethod empirical strategy and exploit both quantitative and qualitative evidence from France. France and its radical RN party provide a particularly useful setting for deepening understandings of geographic divides in PRR support and the residential constraints underlying them. Not only is RN one of the longest-standing PRR parties in Europe, but its electoral bases have also gradually shifted from its early strongholds in structurally deprived, ethnically diverse urban neighborhoods to peri-urban and rural localities that often are in many ways disassociated from the party’s key agenda. Along with this shift, RN has increased in influence: in the latest 2017 presidential elections, its leader Marine Le Pen (MLP) gained a record-breaking 33% of the votes.

To test my theory, I first construct an original, multitiered subnational-level dataset of electoral, economic, demographic, and service infrastructure data to examine whether residential constraints are associated with PRR support in the 2017 presidential elections. I then employ a “most-similar-systems” design (Teune and Przeworski Reference Teune and Przeworski1970) and draw on participant observation and interviews with 40 experts, residents, and politicians in paired high- and low-PRR localities in southwestern France, a region where the PRR has sharply increased in influence but the effects of immigration and globalization remain limited. I find robust evidence of the hypothesized relationship: the PRR is stronger in areas where locals are less mobile, access to economic opportunities and services is compromised, and residential constraints limit residents’ ability to respond to local conditions.

This study contributes to scholarship and contemporary debates on PRR parties on several fronts. First, I advance a novel argument about residential constraints that research on PRR parties has yet to consider. By placing emphasis on political geography and subnational-level dynamics, I challenge prominent accounts of PRR voting as primarily a cultural backlash that has little to do with economic grievances (Mutz Reference Mutz2018; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Rydgren Reference Rydgren2003). Instead, I offer a novel and nuanced geopolitical account of the material foundations of cultural resentments and reactionary attitudes and bring to light the importance of relative economic grievances intimately tied to, and generated by, residential constraints. In so doing, I add new insights to scholarship on the relative economic determinants that underlie PRR support and on how these economic and cultural factors both interact and structure spatial divides in PRR voting and attitudes (Adler and Ansell Reference Adler and Ansell2019; Burgoon et al. Reference Burgoon, van Noort, Rooduijn and Underhill2019; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017, Reference Gidron and Hall2020; Kurer Reference Kurer2020; McNamara Reference McNamara2017). By calling attention to residential mobility and constraints, I also contribute to broader debates in comparative politics about the changing nature of political competition in postindustrial democracies.

The Political Geography of the PRR

Despite the considerable attention given by academics and pundits alike to understanding PRR parties’ (recent) electoral successes, most research on the PRR to date has examined either micro- or macro-level determinants of PRR parties’ performance, overlooking subnational variation in their performance (Golder Reference Golder2016). Thus, although many scholars have highlighted the important role that local contexts play in influencing attitudes or political behavior (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2010; Newman Reference Newman2013), the specific ways in which they affect receptiveness to the PRR continue to be widely debated.

Much of this debate has revolved around whether the roots of PRR support are primarily cultural or economic. On the one hand, several scholars have examined the local conditions under which ethnic diversity affects anti-immigration attitudes and PRR support, not least because a wealth of scholarship highlights cultural factors and hostility toward immigration, xenophobia, and racism as key predictors of PRR votes at the individual level (e.g., Lubbers, Gijsberts, and Scheepers Reference Lubbers, Gijsberts and Scheepers2002; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Rydgren and Ruth Reference Rydgren and Ruth2011). For example, some studies suggest that PRR parties can be particularly appealing to voters living in ethnically diverse and immigrant-dense areas (Coffé, Heyndels, and Vermeir Reference Coffé, Heyndels and Vermeir2007; Gest Reference Gest2016; Mayer Reference Mayer and Barker1992). Others, by contrast, have argued that exposure to and contact with immigrants decrease perceptions of threat and intolerance (Allport Reference Allport1954; Biggs and Knauss Reference Biggs and Knauss2011) or that it is rapid demographic change, rather than the level of local diversity, that activates cultural threats and hostile reactions to immigration (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2010; Newman and Velez Reference Newman and Velez2014; Patana Reference Patana2020). A number of scholars have also noted the existence of a “halo effect,” finding anti-immigration attitudes and PRR support to be stronger in relatively homogeneous areas that are close to or within regions that are more diverse (e.g., Bon and Cheylan Reference Bon and Cheylan1988; Bowyer Reference Bowyer2008; Della Posta Reference Della Posta2013; Evans and Ivaldi Reference Evans and Ivaldi2020; Perrineau Reference Perrineau1997; Rojon Reference Rojon2013; Rydgren and Ruth Reference Rydgren and Ruth2013). Self-selection and sorting into more ethnically diverse large cities, it has also been argued, explain the more positive immigration attitudes in these areas (Enos Reference Enos2017; Gallego et al. Reference Gallego, Buscha, Sturgis and Oberski2016; Maxwell Reference Maxwell2019).

On the other hand, a large body of scholarship has emphasized the economic underpinnings of the PRR vote. For example, scholars have argued that globalization and transnationalism have created new “modernization” grievances that divide citizens into “winners” and “losers” (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008). In line with this logic, studies have shown how those most directly and strongly affected by economic restructuring and isolated from its benefits are most likely to turn to PRR parties and be receptive to their protectionist and nationalist appeals (Arzheimer Reference Arzheimer2009; Kitschelt and McGann Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2008; Lubbers, Gijsberts, and Scheepers Reference Lubbers, Gijsberts and Scheepers2002; Minkenberg Reference Minkenberg2000).

Although this research provides important insights into the initial or “traditional” bases of the PRR, micro- and macro-level analyses of these parties’ contemporary performance have led several scholars to discount the role of economic anxiety in understanding it. They point to the weak correlation between individual-level economic conditions (e.g., unemployment, low level of income), white working-class status, and the PRR vote (Carnes and Lupu Reference Carnes and Lupu2021; Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2018; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019) or to the fact that PRR parties have performed stronger in wealthier European countries with strong welfare states and relatively low levels of unemployment (Mudde and Rovira Kaltwasser Reference Mudde and Kaltwasser2018).

Partly in response to this weak relationship, scholars have shifted their attention more recently to economic geography and importantly demonstrated the ways in which territorial and wealth inequalities (Adler and Ansell Reference Adler and Ansell2019; Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Frieden Reference Frieden2018; Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose2018) underpin PRR support at the subnational level. These studies show how PRR rhetoric has strong appeal in “left-behind,” “rust belt” regions especially hard hit by deindustrialization, global import shocks, long-term structural decay, or persistent poverty.

Another growing body of scholarship has similarly called attention to the ways in which place-based identities and (rural) consciousness shape electoral choices and PRR backlash (Cramer Reference Cramer2016; Fitzgerald Reference Fitzgerald2018; Lee, Morris, and Kemeny Reference Lee, Morris and Kemeny2018). Important recent work has illuminated how strong attachments to one’s locality (Fitzgerald Reference Fitzgerald2018; Hochschild Reference Hochschild2016; Lee, Morris, and Kemeny Reference Lee, Morris and Kemeny2018) or resentment about its (perceived) deprivation with respect to thriving urban metropolitan areas (Cramer Reference Cramer2016; Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose2018) can strongly affect receptiveness to PRR rhetoric.

Although this research advances our understanding of subnational variation in significant ways, it leaves important dimensions of the PRR’s growing popularity underexplored. First, PRR parties’ recent electoral shares across Western democracies clearly demonstrate that their appeal extends far beyond areas that are objectively deprived, structurally poor, or the hardest hit by globalization. Moreover, these studies also fall short in explaining why and how these economic geographies translate into support for parties that capitalize specifically on anti-immigration rhetoric and cultural grievances. Nor can PRR support be reduced to predominantly cultural explanations suggesting that hostility toward immigration is more prevalent in certain areas over others. In France, for example, polls consistently show that the proportion of French citizens holding negative views about immigration is much higher than the PRR’s vote shares (CEVIPOF 2012, 2017). The conditions under which such latent attitudes affect electoral choice thus require further explanation.

Second, although the focus on place-based identity and resentment sheds important light on spatial patterns in PRR support, few studies have paid attention to how local economic realities shape these place-based considerations, particularly how local residents perceive and respond to territorial inequalities and deprivation. Given previous research’s emphasis on concern and resentment about the state of individual or local conditions as a central motivation of PRR vote, greater focus on these dimensions is warranted.

I build on and contribute to this growing body of scholarship by examining subnational variation of PRR support through the lens of residential constraints. In doing so—and expanding on recent individual-level research on the economic determinants of the PRR vote (Burgoon et al. Reference Burgoon, van Noort, Rooduijn and Underhill2019; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017, Reference Gidron and Hall2020; Kurer Reference Kurer2020)—I bring to light the importance of relative economic concerns related to residential constraints and show how economic and cultural factors interact and structure the political geography of PRR support.

Theory of Residential Constraints

The Causes of Residential Constraints

Residential constraints have been largely overlooked in research on political behavior and political economy more generally and in PRR studies specifically. Several factors, however, point to their increasing relevance for understanding the political economies and changing party landscapes of postindustrial societies—not least because of growing concerns about the increasing number of individuals who are unable to live close to where they work, others who are displaced from their neighborhoods, and citizens finding themselves “locked in” declining areas (Ganong and Shoag Reference Ganong and Shoag2017; Inchauste et al. Reference Inchauste, Karver, Kim and Jelil2018; Le Galès and Pierson Reference Le Galès and Pierson2019).

Although they may be a more subtle or hidden consequence of economic restructuring, globalization, and growing transnationalism, residential constraints are closely connected to these broader processes. Indeed, despite increasing pressure and demand for workforce flexibility and mobility in postindustrial societies, national governments have pursued policies that hinder such mobility. Structural changes in the economy have contributed not only to the decline of manufacturing and traditional industry but also to the centralization and concentration of economic opportunities, service delivery, and infrastructure around larger urban agglomerations and metropolitan cities (Frieden Reference Frieden2018; Guilluy Reference Guilluy2016; Lee, Morris, and Kemeny Reference Lee, Morris and Kemeny2018; Le Galès and Pierson Reference Le Galès and Pierson2019; McNamara Reference McNamara2017; Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose2018).

Although such a deep embrace of agglomeration may have been beneficial to national economies, productivity, and growth more generally, it has also contributed to widening territorial inequalities within countries. Moreover, and crucially, although major interregional migration from declining to dynamic areas has followed these developments, considerable—and far larger than anticipated—numbers of citizens have stayed behind, thus calling into question the widely held assumption of perfect mobility at the heart of theories of urban development and economics (e.g., Glaeser Reference Glaeser2011; Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose2018). If anything, residential mobility rates in many Western democracies have declined rather than increased since the 2000s (e.g., INSEE 2017; US Census Bureau 2018).

What explains this declining mobility? Residential choices and decisions to “stay put” reflect diverse considerations related to social networks, attachment, opportunities, and service provision. For many, however, such choices have become increasingly constrained, given important “pull” and “push” factors that keep citizens out of prosperous areas or locked in ones outside them. From a “pull” perspective, the concentration of economic activity and services around larger urban agglomerations has steadily increased the demand for and costs of housing in these areas, while the stock of affordable housing has continued to diminish (Le Galès and Pierson Reference Le Galès and Pierson2019). Large metropolitan dynamic cities have thus become increasingly unaffordable (Inchauste et al. Reference Inchauste, Karver, Kim and Jelil2018; Le Galès and Pierson Reference Le Galès and Pierson2019), resulting in some groups being gradually pushed out of them (Ganong and Shoag Reference Ganong and Shoag2017). Unsurprisingly, the composition of city populations has shifted in recent decades, as urban agglomerations become increasingly composed of high-skilled individuals (Ford and Jennings Reference Ford and Jennings2020; Guilluy Reference Guilluy2016).

“Push” factors keep citizens “locked” in areas that are less prosperous and desirable. Areas isolated from the benefits of agglomeration have witnessed a decline in housing prices and rents. This is a particular concern for homeowners, who are generally less mobile to begin with; in particular, declining house prices risk trapping households with modest home equity (Bloze and Skak Reference Bloze and Skak2016; Chan Reference Chan2001). In less desirable and dynamic areas, selling times are often long, and their homes’ current property value may not correspond to the initial investment or mortgage, further constraining mobility in these areas.

Importantly, these dynamics related to residential constraints bring to light a specific set of highly localized, geographically bound concerns and grievances that are in many ways distinct from and go beyond the more objective geographic dimensions of economic restructuring like structural or persistent poverty, deindustrialization, or global trade shocks (Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Frieden Reference Frieden2018; Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose2018). Indeed, agglomeration, coupled with locals’ limited mobility and options to respond to it, generates a set of relative economic grievances and renders them highly salient in many localities that may otherwise appear unaffected by the more objective, albeit related, hardships (e.g., where unemployment is low and locals are far from impoverished). In these areas, access to employment, for example, entails long and increasing daily commutes. The growing distance to services and the unavailability of affordable public transport options, too, have important financial and time-related costs and consequences. A focus on residential constraints thus underscores the importance of these relative, yet consequential, grievances overlooked in studies focused on the more objective dimensions of long-term structural decay. As such, it adds to recent individual-level studies that similarly call attention to relative economic conditions underlying the PRR vote (Burgoon et al. Reference Burgoon, van Noort, Rooduijn and Underhill2019; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017, Reference Gidron and Hall2020; Kurer Reference Kurer2020).

The Political Consequences of Residential Constraints

Understood as limiting citizens’ capacity to respond to growing spatial inequalities and rendering salient a set of relative economic grievances, residential constraints provide an important lens through which PRR parties politicize, and residents interpret, broader demographic and economic societal change.

Hirschman’s influential study Exit, Voice, and Loyalty (Reference Hirschman1970) offers a useful framework for conceptualizing how residential constraints shape citizens’ behavior and electoral choices. Initially theorized to explain how individuals and groups respond to organizational, firm, and state decline, Hirschman’s framework posits that actors face two options: exit (withdraw from the organization) or voice (express discontent). Viewed through this framework, the PRR vote can be considered as voice for residentially constrained individuals whose exit options are blocked or limited.

Indeed, in the current economic context, where opportunities are increasingly concentrated and flexibility, labor mobility, and short-term contracts are the norm, residentially constrained individuals living at a distance from more dynamic agglomerations face challenges in responding to these changing demands and conditions. At the same time, they are confronted with relative grievances related to accessing opportunities. Residentially constrained individuals should thus be more likely to support the PRR’s protectionist policies, which seek to limit further delocalization and the concentration of economic opportunities.

The logic is similar for immigration. As mentioned earlier, anti-immigration sentiments are much more widespread than actual vote shares for anti-immigration parties. PRR parties also perform better in homogeneous localities with few immigrants than in ethnically diverse urban areas. The concentration of service provision around larger urban agglomerations helps explain these geographic patterns. Because of the erosion of local service provision in the smaller, more isolated communities, accessing services entails increasing and often considerable financial and time-related costs. Thus, residentially constrained locals who pay taxes that finance services but struggle to access them should become more receptive to PRR parties’ welfare chauvinistic rhetoric on immigrants (typically concentrated around urban areas and large cities) being favored over “natives.”

Studies have also shown how proximity to diverse areas or local ethnic change explains heightened anti-immigration attitudes (see the previous section). Scholars have also argued that “native” residents self-select into homogeneous localities (Hall and Crowder Reference Hall and Kyle2014) or that their likelihood of relocating increases as their communities become demographically more diverse (Crowder, Hall, and Tolnay Reference Crowder, Hall and Tolnay2011; Perrineau Reference Perrineau1997). In a similar vein, Velez (Reference Velez2018) importantly demonstrates how hostility toward immigrants is stronger among locals confronted with ethnic change and who are residentially constrained than among residents living in “exit-friendlier” localities. Thus, although self-selection and sorting undoubtedly play a key role in understanding immigration attitudes and PRR support (Enos Reference Enos2017; Gallego et al. Reference Gallego, Buscha, Sturgis and Oberski2016; Maxwell Reference Maxwell2019), some of the anti-immigration backlash outside the diverse, “cosmopolitan” cities may well be attributable to residentially constrained individuals contesting the effects of immigration, because their means of responding to it in other ways are limited.

In sum, I evaluate the following hypotheses:

H1a. PRR support is higher in areas where locals are more residentially constrained.

As elaborated earlier, low mobility can also be driven by considerations other than residential constraints, notably by non-economic factors such as strong local attachment or social ties. However, the dynamics of discontent theorized here suggest that PRR support is particularly strong when residential choices and constraints are rooted in economic considerations related to housing markets. Reflecting this distinction,

H1b. PRR support is higher when residential choices and constraints are rooted in economic considerations.

Rassemblement National: A Growing but Geographically Divided Electorate

Founded in 1972, the Rassemblement National (RN) is one of the longest-standing and most influential PRR parties in Western Europe. Since the 1980s, it has exerted considerable political leverage in the French political scene (Mayer Reference Mayer, Bartels and Bermeo2014). In 2017, Marine Le Pen (MLP), the leader of the PRR Rassemblement National, gained a record-breaking 21.3% vote share in the first round of the presidential elections. She then advanced to the second round, in which she was the preferred candidate of one-third of French voters. Although MLP did not win the presidency, her performance created a stir not only because –for only the second time in French political history—a radical right candidate advanced to the second round of the election, but also because it revealed the widespread and growing appeal of the PRR among French citizens.

Part of this growing appeal is attributable to MLP herself, who took over the party reins from her father Jean-Marie Le Pen in 2011. Distancing herself from the reactionary single-issue party led by her father, MLP undertook major reforms to “de-demonize” the party and make it a viable alternative to the two mainstream parties dominating the political scene (Betz Reference Betz, Kriesi and Pappas2015). Indeed, MLP places strong emphasis on France’s republican and “laicist” principles (i.e., nativist nationalism; Betz Reference Betz, Kriesi and Pappas2015; Perrineau Reference Perrineau2014). RN’s social welfare agenda combines expansive social protection with an emphasis on “priorité nationale”: native-born citizens should be prioritized over immigrants on access to employment and welfare. The party is also highly critical of the effects of the EU and globalization and uses a populist discourse that targets the “losers” of economic restructuring, defending the interests of “ordinary people” or “the ones paying the price of globalization” (Betz Reference Betz, Kriesi and Pappas2015; Mergier and Fourquet Reference Mergier and Fourquet2011). RN’s growing vote share in national, regional, and European elections points to the success of this strategy (figure 1).

The party’s growing popularity has coincided with a considerable shift in its electoral geography. Its initial strongholds were in ethnically diverse and economically depressed, declining urban areas (Mayer Reference Mayer and Barker1992; Perrineau Reference Perrineau1997). From 2002 onward, however, RN’s influence in urban areas has waned but has instead strongly increased in rural and peri-urban areas (Gombin Reference Gombin2015). Indeed, and as is well established, the correlation between local ethnic diversity and RN support is negative, nor is there much of a relationship between the traditional industry-heavy areas and RN support (figure 2). Moreover, despite major regional divides in RN support—its highest electoral support was traditionally recorded in the economically depressed, postindustrial north and northeast, as well as the relatively immigrant-dense south—the party now records significant vote shares across the country. Over-time, growth in RN support has also been stronger outside its traditional zones of influence. I focus on residential constraints to understand these shifts and rise in support in recent elections.

Empirical Strategy

I employ a multimethod research design. First, I conduct a quantitative test of the theory by constructing an original multilevel dataset of French communes (the lowest level of administrative division) nested within 96 departments. France’s more than 35,000 communes have an average population of 1,870 inhabitants; most have less than 1,000 inhabitants.Footnote 6 I complement this subnational-level analysis with individual-level evidence from 40 interviews and participant observation in the southwestern Department of la Charente-Maritime conducted in 2017–18.

This analytical strategy has several advantages. First, it deepens understanding of the local conditions that fuel reactionary attitudes and resentment. Second, despite increased attention in spatial divides in anti-immigration attitudes and PRR support (e.g., Adler and Ansell Reference Adler and Ansell2019; Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Evans and Ivaldi Reference Evans and Ivaldi2020; Frieden Reference Frieden2018; Maxwell Reference Maxwell2019; Rodríguez-Pose Reference Rodríguez-Pose2018), the vast majority of this scholarship is quantitative in nature and thus overlooks the political salience of lived experiences and realities, especially as they relate to residential constraints.Footnote 7 By illuminating how PRR voters make sense of themselves, their localities, and their grievances, the qualitative evidence thus illustrates how residential constraints powerfully shape their lives and political behavior and generate relative economic concerns thus far overlooked in PRR research.

A Quantitative Test of Residential Constraints

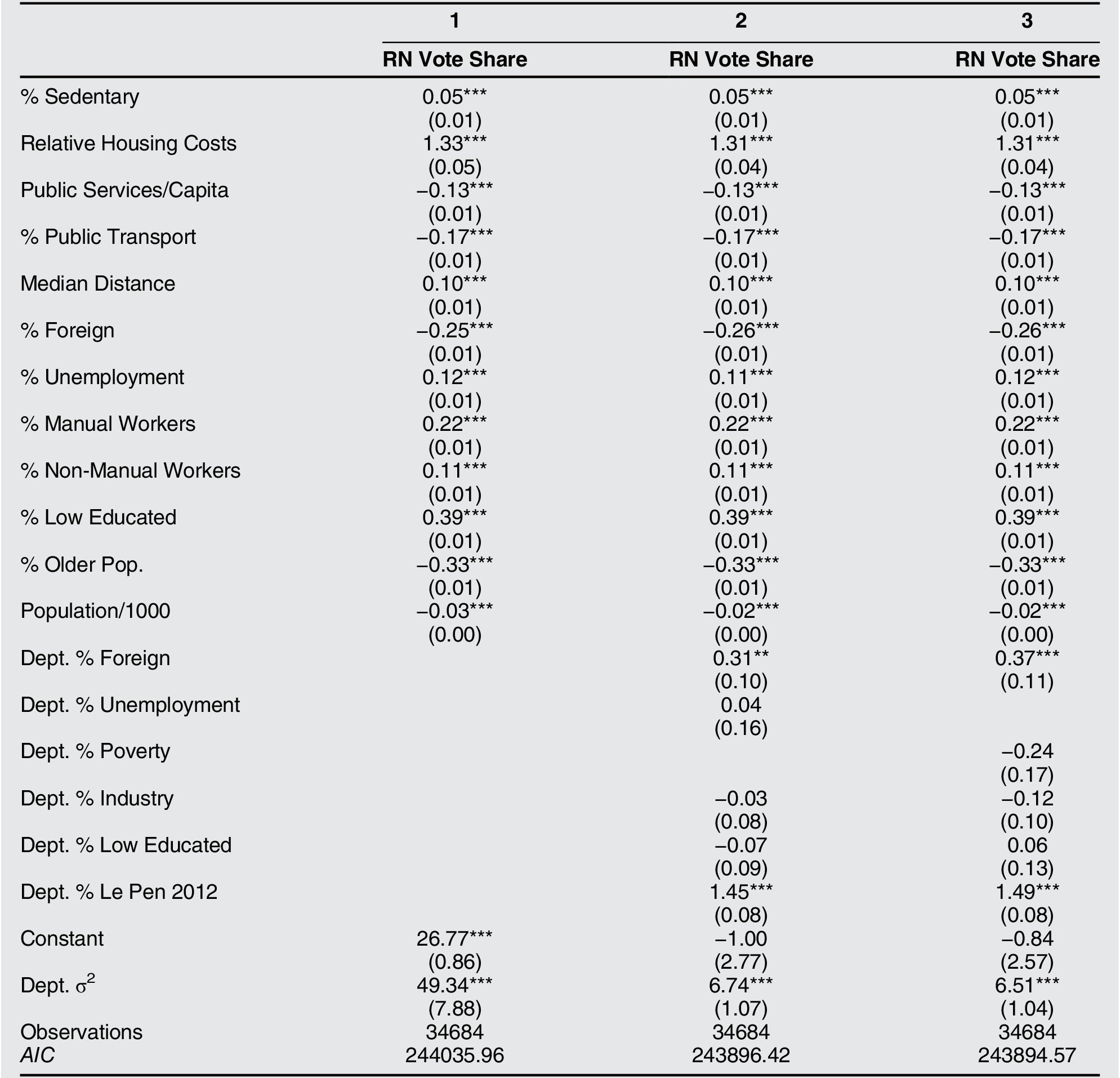

I employ two-level random intercept models, in which communes are nested within departments. This multilevel strategy enables me to (1) take into account the hierarchical nature of the data and (2) further consider and examine regional contextual influences on, as well as traditional strongholds in, RN support. The dataset draws on electoral, economic, sociodemographic, and unique, newly available rental price data collected by the Ministry of the Interior (2020), the Observatory of the Ministry of Territorial Cohesion (2020), and the Ministry of Ecology (2021).

As the dependent variable, I use the vote share for MLP in the second round of the 2017 presidential elections.Footnote 8 To investigate the effects of residential constraints on PRR support, I include several key measures (see the appendix for descriptive statistics).Footnote 9 First, I include a measure of the local sedentary population, defined as the proportion of households having lived in the commune for 10 or more years.Footnote 10 Second—and crucially, given that housing costs play a central role in residential mobility considerations—I calculate a measure of relative housing costs: the difference between the average rent of a house per square meter in the commune and the departmental capital. The capital is most often the largest city in the department and where opportunities and services tend to be concentrated.Footnote 11 As such, it provides a useful reference point to evaluate local-level mobility considerations and constraints: the larger the difference between these housing costs, the more residentially constrained are locals likely to be.

To examine the effects of other key relative economic grievances closely tied to residential constraints, I calculate a measure of public services per capita.Footnote 12 Because access to public services is a right and is universally guaranteed, local service provision can be considered a relative economic concern; their agglomeration in certain areas makes it harder to access them in other areas. Services also constitute a key indicator of the “desirability” of a locality: they simultaneously make localities attractive to potential newcomers and reduce the need for current inhabitants to relocate or endure long commutes to access them.Footnote 13 As other measures of relative grievance, I include the median distance to work in kilometers and the share of the population using public transport for daily work commutes. Long commutes and the lack of public transport are important and often costly relative concerns for residentially constrained individuals, who may otherwise be employed and financially secure but who live in areas where access to employment or services makes commuting a daily necessity.

I also include several commune-level contextual variables to control for demographic and economic conditions. First, I include the proportion of foreign nationals.Footnote 14 To investigate the effects of objective economic strain, I calculate the local unemployment rate (share of unemployed/total 15 + -year-old workforce). Theories of globalization and modernization “losers” also predict that individuals with low(er) levels of education and skills and those occupying jobs in manual labor should be more receptive to PRR appeals. I therefore control for the proportion of non-manual workers (“employés”) and manual workers (“ouvriers”) and those with low education (the share of 15 + -year-olds with no higher education degree and not in an educational program).

The models also adjust for the share of over 65-year-olds in the local population. There are two key reasons for this. First, from an (im)mobility perspective, older individuals (notably retirees) tend to be more financially secure than working-age populations; they are thus much less likely and have less need to relocate. Older individuals’ relatively stable status and stronger attachment to mainstream parties make them also less likely to turn to the PRR (Guilluy Reference Guilluy2016). Finally, to consider the rural–urban dimensions of RN support and significant differences in size of the communes, I control for the population size (per 1,000 people).

These commune-level variables (level 1) are nested within departments (level 2). At the departmental level, I include measures of ethnic diversity, unemployment, traditional industry employment, the low educated, the poverty rate (60% below the median income),Footnote 15 and the 2012 RN vote share. I leverage this additional departmental-level information to investigate—as previous research suggests (e.g., Della Posta Reference Della Posta2013; Evans and Ivaldi Reference Evans and Ivaldi2020; Rojon Reference Rojon2013)—whether and how the effects of immigration and objective economic conditions on RN support vary at different levels, as well as how contemporary PRR support may differ from regions where its traditional strongholds lie.

The multitiered, spatial examination of MLP’s performance in the 2017 presidential elections yields several noteworthy findings and provides empirical support for the hypothesized relationship between residential constraints and PRR support at the local level (H1a). First, the share of the local sedentary population is positively associated with RN support, suggesting that areas whose residents are less mobile are more receptive to PRR appeals. This effect is statistically significant and holds to different model specifications. Moreover, because the models control for the share of older individuals, the results reflect working-age populations’ (im)mobility dynamics and are not distorted by older generations’ differing mobility considerations. Substantively speaking, however, the effect of sedentariness is relatively small: all else equal, a 10% increase in the share of local sedentariness is expected to lead to a 0.5% increase in PRR support. This weak effect therefore suggests that sedentariness may not be the best proxy for blocked mobility driven by structural constraints.

Relative housing costs provide important additional leverage for understanding these structural constraints (H1b). Indeed, the larger the difference in average housing cost between the commune and the departmental capital, the more residentially constrained are locals likely to be. Consistent with expectations, relative housing costs are positively associated with the PRR vote. Substantively speaking, this effect is also very strong: on average, a 1 euro increase in this difference (per m2) is associated with an approximate 1.3% increase in MLP support. These findings contribute to recent research (Adler and Ansell Reference Adler and Ansell2019; Ansell et al. Reference Ansell, Hjorth, Nyrup and Larsen2021) that has examined connections between housing prices and PRR support in the Nordic countries, Brexit, and at the departmental level in France. By focusing on mobility and relative housing costs, I deepen understanding of how and why housing costs influence behavior and attitudes.

The key measures of relative economic conditions generated by residential constraints—public service and transport availability and median distance to work—also conform with theoretical expectations. First, there is a strong negative correlation between local service provision and PRR support: the more public services a locality has per capita, the worse RN performs. Substantively speaking, the effect is notable: on average, an increase of one additional service is expected to lead to a 0.13% decrease in RN support. This finding also sheds theoretical light on the conditions under which welfare chauvinism may influence PRR voting. In line with Cavaillé and Ferwerda (Reference Cavaillé and Ferwerda2019), it points to variation in access to public in-kind services as powerfully influencing receptiveness to the PRR’s welfare chauvinistic appeals. In the context of growing spatial inequalities in public service provision, residents who face difficulties accessing them may indeed become more receptive and sensitive to narratives of public finances being spent on “out-groups,” while “natives” and their needs are “ignored.”

The hypothesized relationships between public transport users, commuting distance, and RN vote are also in line with theoretical expectations. A 10 km increase in the local median commuting distance, for example, is expected to increase the PRR’s vote share by 1%. The share of daily public transport users, in contrast, is negatively correlated with RN voting: a 10% increase in their share is expected to lead to a 1.7% decrease in MLP support. These results provide further evidence about how relative economic grievances intimately tied to residential constraints structure PRR support. Areas where distances to work are shorter and access to public transport is available are more desirable; citizens making residential choices thus prefer these areas over others. Those who are constrained to areas where commutes are long and costly and public transport is lacking, in contrast, are more likely to voice their resentment brought about these relative concerns by voting for the PRR. The results are also robust to excluding large communes from the sample, suggesting that the spatial patterns do not merely reflect an urban–rural divide; there exists important variation across rural and peri-urban areas in residential constraints and relative grievances (see the appendix).

Although not the primary focus of this study, the analysis also offers insights on the conditions under which local demographic and objective economic factors shape RN support. As expected, and in line with previous research, the level of local ethnic diversity is negatively correlated with RN voting. The share of immigrants at the department level, in contrast, is positive. These contrasting findings at different levels of aggregation conform with previous research (Della Posta Reference Della Posta2013; Evans and Ivaldi Reference Evans and Ivaldi2020; Rojon Reference Rojon2013), suggesting that threat and fear of immigration may indeed depend on the scale. From the viewpoint of residential constraints, and in line with the “halo effect” dynamic that Perrineau (Reference Perrineau1997) stipulates, this logic also makes sense; residentially constrained individuals living in more diverse departments may indeed more strongly resent the perceived unjust distribution of state resources and consider their options to respond to ethnic change more limited.

The association between the local unemployment rate and RN vote share, by contrast, is positive. Given the weak evidence when it comes to unemployment and PRR support especially at the individual level, this is a noteworthy finding; the positive correlation between unemployment and PRR support may reflect the lack of economic opportunities and the long commutes required to access them. Spatial mismatches in employment can indeed place residentially constrained individuals at risk of benefit and unemployment traps (OECD 2005).Footnote 16

PRR support is also stronger in communes with higher shares of the “losers of globalization”: the shares of both the working-class local population and those with low levels of education are positively correlated with RN’s performance. Areas where the PRR performs well are thus those where populations are economically worse off, but not necessarily deindustrializing. Combined with the positive effect of unemployment, these findings have implications for mobility as well. Ganong and Shoag (Reference Ganong and Shoag2017) for example, show that high costs of housing play an important role in understanding high- and low-skilled workers’ migration patterns: whereas high-skilled individuals migrate to areas characterized by high incomes and economic opportunity, low-skilled workers are forced to leave them. Recent research by Bergman and colleagues (Reference Bergman, Chetty, DeLuca, Hendren, Katz and Palmer2019) also reveals how barriers to moving, rather than neighborhood affordability, family networks, social connections, or employment, explain why lower-income individuals tend to stay put in areas offering few opportunities for income mobility. Davezies (Reference Davezies2012), too, shows that individuals in lower-skilled (i.e., manual) occupations are less likely to relocate in the event of dire economic circumstances or unemployment than are those occupying high-skilled positions. When they do relocate, however, it is not to more dynamic, prosperous areas but to nearby locations that are only marginally better off. This makes intuitive sense, because not only is remuneration for manual work lower (thus making prosperous areas inaccessible), but this type of work also makes individuals more tied to a “place” compared to, say, the service sector, further constraining their mobility. Social mobility is indeed closely tied to geographic mobility: in France, upward mobility from the working- to middle class is much higher in the capital Île-de-France region than in other areas (Dherbécourt Reference Dherbécourt2015).

Crucially, economic conditions appear to have little effect on contemporary PRR support at the departmental level; there is no detectable association between the share of unemployed and low educated, industry employment, or poverty and the MLP vote when controlling for RN’s previous vote share. Thus, although RN may have its traditional strongholds in the more structurally depressed, deindustrialized regions, its rise in popularity in recent elections extends far beyond these areas. These findings, combined with those at the commune-level, therefore underscore the importance of paying further attention to relative concerns and conditions like those rooted in residential constraints. Additional focus on such conditions thus helps refine our understanding of the economic geographies of PRR support and, importantly, why contemporary PRR parties perform well in areas far beyond those hard hit by globalization, trade shocks, and structural poverty.

Taken together, these findings contribute to recent individual-level research that moves beyond the cultural-economic juxtaposition by highlighting how relative concerns related to status anxiety or decline better predict PRR vote (Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017, Reference Gidron and Hall2020; Kurer Reference Kurer2020). As residential constraints relegate individuals to living far from prosperous areas where opportunities are concentrated, and strongly limit individuals’ possibilities of responding to incentives to relocate and to local conditions more generally, they can be considered as an important mechanism through which status concerns and resentment are activated.

To be sure, and as discussed earlier, residential constraints are a multidimensional issue that affects certain individuals and groups more than others; mobility and residential choices are closely connected to educational qualifications, skills, and occupations. Although the available data are limited in their capacity to estimate causal effects, the analyses do reveal a robust association between the key measures of residential constraints and PRR support, even after adjusting for other commune- and department-level socioeconomic characteristics associated with PRR support. As such, these analyses both provide an important first step in identifying how residential mobility considerations and constraints shape electoral choices and call for more systematic attention to, and inclusion of, such measures in future research.

Qualitative Case Study: La Charente-Maritime

I next draw on a qualitative analysis of 40 interviews with RN supporters, residents, politicians, and experts, as well as participant observation, in paired high- and low-RN support communes in the Department of la Charente-Maritime (CM). CM is a “hard case” for conventional theories of PRR support. Although it is far from resembling one of the “traditional” PRR strongholds (Gombin Reference Gombin2015), RN support has grown rapidly and faster there than in most other departments since the early 2000s (SudOuest 2017). This increase is puzzling, given consensus around the fact that CM has remained relatively unaffected by the key issues that the PRR emphasizes. First, its ethnic diversity is one of the lowest in the country (3.3% compared to the national average of 9%; INSEE 2020). Second, the effects of globalization or deindustrialization are considered modest at best. The role of traditional industry in the region has traditionally been limited (9.8% of the workforce is employed in the industrial sector compared to 13.6% nationally). Consequently, it has not undergone “any major structural transformations either.”Footnote 17 Unemployment is also around the national average. France’s EU membership is relatively positively perceived: CM’s agriculture is “mostly centred around cognac and wine, which are very profitable sectors”Footnote 18 and heavily protected by the EU.Footnote 19

To identify intersystemic differences while holding “common systemic characteristics” (Tarrow Reference Tarrow2010) constant, I use a “most-similar systems” design (Teune and Przeworski Reference Teune and Przeworski1970) and pair otherwise similar communes (i.e., low levels of ethnic diversity, low/average levels of economic distress, and similar size and type of locality), but that differ on their level of PRR support (see the appendix).

The qualitative analysis reveals how residential constraints are a central lens through which individuals perceive and understand themselves, their localities, and grievances. It also illustrates how they make salient relative economic concerns that boost PRR support. These concerns are also much more prevalent in high-PRR areas compared to demographically and economically similar communes where the RN has performed much worse. Table 1 presents a summary breakdown of the prevalence of the key concerns identified by locals in the surveyed communes. It also includes the percentage of regional experts who identified these grievances as key to understanding rising RN support within the department. Crucially, the key economic concerns identified by individuals relate to those that are relative and tied to residential constraints, rather than objective concerns related to deindustrialization, the decline of traditional industry, structural hardship, or persistent poverty. In contrast, I found little meaningful variation in attitudes toward immigration, the EU, and globalization across the localities. Strikingly, however, the way individuals perceive and discuss these broader issues is also closely tied to concerns about residential constraints and locals’ perceived capacity to respond to them.

Table 1 Residential Constraints and PRR Support

Notes: Table reports unstandardized coefficients. Standard errors in parentheses.

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Residential Constraints and the PRR

As shown in table 2, residential mobility, access to services, and opportunities and locals’ options to address these grievances were prominent in high-PRR communes. Notably, locals in these areas typically were far from attached to their communes; many described them as “bedroom communities,”Footnote 20 questioned their choice to live in high-PRR communes,Footnote 21 and stressed the high costs of housing and the consequent difficulties of relocating closer to more “desirable,” or prosperous areas. Several mentioned that their reasons for living in these localities were “mainly financial”; others said they moved there because of a lack of better options.Footnote 22 Others relatedly cited “cities sucking up all the jobs”Footnote 23 and services as a major challenge and expressed resentment caused by long and expensive commutesFootnote 24 and “everything leaving”Footnote 25 as major reasons for RN support.

Table 2 Key Challenges

Objectively speaking, however, these localities and the majority of their inhabitants were far from impoverished or suffering from structural hardship on several fronts. For example, a local politician of a quaint and peaceful peri-urban coastal town—where MLP won both rounds of the 2017 election—was quick to note how the commune is a popular tourist destination, how most of its inhabitants are homeowners and thus have at least modest amounts of wealth, and that unemployment is low. The lack of local economic opportunities and services, by contrast, was a cause of major concern and resentment among local inhabitants, making commuting by car a necessity that puts a considerable strain on household budgets. It is thus a major concern and one that is viewed through the lens of constrained mobilityFootnote 26 :

Local politician: “Employment opportunities are the major concern. The dynamic zones of economic activity are far, and although we have new public transport [buses], the routes do not often serve [many parts of] the commune well.”

PP: “How about opportunities here in the commune?”

Local politician: “No, for qualified jobs you need to go to the city. [Local] jobs are mostly precarious…. Many locals have modest means, and with those, it’d be very hard to live in a city. Younger, educated people leave, but those who stay have few opportunities and skills. I am not sure if these people would really like to leave “their country” but they would have little means of doing so even if they wanted to!”Footnote 27

Although they do not experience structural hardships or poverty, individuals in these areas have relatively modest budgets and are vulnerable to expenses related to long and increasing commutes by car to access jobs and services. Major highways are also privatized, which leaves locals with two choices: either pay considerable amounts of money on tolls or choose alternative routes, which typically are longer and less well maintained. Tellingly, a disgruntled RN-supporting local compared the situation to physical barriers:

Local: “To drive to Paris from here, you got to pay more than 40 euros just in tolls; it’s like they’re creating barricades for us to even enter cities!”Footnote 28

Service provision is an equally key relative concern for RN supporters and residents in high- PRR communes and is closely connected to residential choices and constraints. A retired elderly woman, her middle-aged son, and his friend, a stay-at-home father—all financially secure, homeowning RN sympathizers living in a commune that recorded one the highest vote shares for MLP in 2017 in the region–stated,

Retiree: “There are no services, or anything here, nothing is done, it’s even hard to get bread during the day! Back in the day we had seven cafes and all the services, we had so much potential!”

Son and friend: “So now, people don’t want to come or live here. I mean why would they, there’s nothing here… . Lots of houses are for sale. We feel abandoned, forsaken.”Footnote 29

In low-PRR communes, residents’ views about and attachment to their localities were demonstrably different, and their grievances were interpreted through a different lens. Despite being similar in size and rurality, employment and homeownership rates, and socio-professional makeup to localities where the PRR has performed much better, they differ considerably in levels of residential constraints. They also differ in appearance: many of the low-PRR communes are surrounded by wine or cognac fields, and the houses and overall image of the towns appear better kept as well.

In stark contrast with high-PRR areas, locals of low-PRR communes consistently described them as places “where people are happy to live,”Footnote 30 desirable localities that have high demand and “very little offer”Footnote 31 for housing, and where “houses are selling at a gain.”Footnote 32 One middle-aged manual worker and his wife were quick to state how, on arrival to their locality, they realized they wanted to live “there or nowhere.”Footnote 33 Many also noted how these communes were not bedroom communities and were viewed as highly desirable areas.Footnote 34 And although local jobs are few and far between and require commuting, inhabitants’ overall satisfaction with their localities made such concerns far less pronounced.

Importantly, in parallel to service provision being a key concern in high-PRR communes, the presence of services in certain communes plays a major role in making those areas sought after.Footnote 35 Like many others, one mayor of a rural low-PRR commune described them as a strong asset:

Mayor: “People come here because of the living environment, because of the location. Once they are here, they will never want to leave! These are people who want to live in the countryside. And we have services, a library, a school, meal services for older people.”Footnote 36

In sum, locals in high- and low-PRR communes understand their communities in starkly different ways. While residentially constrained locals in high-PRR areas struggle to respond to grievances related to accessing services and opportunities, as well as long commutes, these issues appear less prevalent in otherwise similar, small, rural, and peri-urban low-PRR areas. This, in turn, has important implications for how individuals perceive themselves and their localities. Residents of low-PRR areas consistently emphasized satisfaction with their communities, whereas high-PRR areas were instead typically characterized with reference to residential constraints. These findings thus reveal important variation in residential constraints and PRR support not only along the urban–rural axis but also across rural areas as well. They also point to the importance of paying further attention to relative economic concerns related to the residential constraints underpinning the growing popularity of the PRR.

Immigration, Globalization and the EU

In contrast to these stark differences in residential constraints between high- and low-PRR communes, I found little evidence of meaningful differences in attitudes toward immigration, the EU, and globalization or their salience. For example, even if the tone and word choices people use to talk about immigration may have differed to a certain extent, residents, politicians, and experts across the political spectrum used a mostly wary and often pejorative tone when talking about the effects of immigration, refugees, or Islam.

Indeed, the key difference between high- and low-PRR areas relates to how immigration is politicized and discussed in relation to residential constraints and spatial inequalities in access to services and opportunities. This observation suggests that part of the heightened hostility toward immigrants in more homogeneous, rural, and peri-urban areas may indeed have important economic underpinnings: anti-immigration attitudes in high-PRR communes were expressed not in terms of cultural grievances but rather through the lens of these local concerns. Notably, the agglomeration of services plays a particularly important role in heightening responsiveness to RN’s welfare chauvinistic rhetoric, as stated by a RN-supporting local:

Local: “They keep putting more resources into neighborhoods with—shall I say—an abundance of people with a foreign background and at the same time, I feel like we owe certain rights and guarantees to our own citizens and residents, especially when it comes to things like education and health care. Life is becoming more and more difficult in our communes, schools are closing or merging [into larger units], and meanwhile in le CalaisFootnote 37 you have food trucks giving free breakfast and lunch to refugees!”Footnote 38

Perceptions of being “stuck” in less desirable areas where opportunities and services are scarce also contribute to heightened hostility toward immigration and its plausible local effects. A baker in a rural high-PRR community, for example, voiced skepticism about locals’ potential reception of immigrants, while also pointing out that the area was hardly one that locals desired to live in or were attached to themselves, asserting that her town lacked “life and dynamism,” had nonetheless considerable living costs, and that “it’d be very hard to move anywhere [nicer] from [t]here.”Footnote 39

Conversations with locals in both high- and low-PRR areas also reveal widespread skepticism and resentment toward the EU and globalization. Most people do, however, acknowledge that “lots of farmers in the area benefit from EU subventions,”Footnote 40 that leaving the EU “does not interest anyone,”Footnote 41 and that France overall hugely benefits from the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).Footnote 42 Crucially, reactions to growing transnationalism are also closely tied to residential constraints. Many residents view these developments as further contributing to the local challenges that individuals in high-PRR communes face, despite there being a consensus about their, if anything, modest effects. This is exemplified by a local politician of one high-support commune:

PP: “Have the EU or globalization affected local life over the past two decades?”

Local politician: “Oh, those are badly viewed here! It’s very easy to blame these things for your own worries, but in reality, their effects are not really felt or seen here.”Footnote 43

In areas where communes and residents struggle to respond to local grievances, the EU and globalization are seen as exacerbating already widening spatial inequalities. For example, many residents in high-PRR areas noted how the EU’s distant, top-down governance system is out of touch with local realities and needs.Footnote 44 With “excessive regulation,”Footnote 45 the “factory of norms”Footnote 46 is simultaneously considered as “distant”Footnote 47 while making many aspects of local life difficult.Footnote 48 Thus, global markets, supranational governance, and EU regulations enforced from above are seen as deepening the existing spatial inequalities. In this context, many locals are receptive to RN rhetoric on how “EU influence … needs to be limited.”Footnote 49 In other words, in high-PRR areas, where local services and opportunities are few and far between, the overall perception that government is detached and unresponsive can easily feed into anti-EU sentiments and pro-RN voting.

Residential Constraints and Party Competition

It is important to note that nothing about these localized, relative grievances makes them the natural domain of the PRR. Why then has the PRR been particularly successful in mobilizing voters in these areas? Conversations with experts and mainstream party officials in the region quickly revealed that it is well known that RN performs well in areas where locals are residentially constrained and where services and opportunities are lacking. For example, an influential conservative right-wing politician instantly identified these issues as the key reason for RN’s rise in the department:

Right-wing politician: “It’s a vote [driven by] exclusion. These are people who live in the periphery, and not by choice. They have difficulties with housing, jobs, employment and don’t have the means to live in cities! … They live in rural areas but do not share any conviviality: they have relatively little contact with their neighbors; the mayors do not know them either. They do not have access to the world they like to resent, the world they see on television, etc.”Footnote 50

A Socialist Party representative shared this view:

Socialist Party employee: [RN supporters] “live in areas with little opportunities, places that vote for [RN] are remote areas… . Racism plays a part, but the main issues relate to financial concerns.… These are places 30 minutes, one hour away from cities where opportunities are more abundant, but people [in these areas] have difficulties moving and finding better opportunities.… If they can, they leave and don’t come back… . These are people with little means, they probably always lived there, but strong local identity, I’m not certain that plays a part.… When you have limited means you have limited choice and opportunities too.”Footnote 51

Despite these issues being well known, RN is currently the only party actively politicizing them. Indeed, the claim that traditional mainstream parties have failed to respond to the specific challenges rural and peri-urban areas face has some merit: all other major parties—including the two mainstream parties (le Parti Socialiste and les Républicains), Macron’s recently established En Marche! and Mélenchon’s radical left la France InsoumiseFootnote 52 —have their electoral bases in more urban areas and major cities, leaving political competition over rural and peri-urban voters to be dominated by the RN. Indeed, although Macron won a landslide victory against Le Pen, the sentiment that he “is disconnected from the countryside” is widespread across high- and low-PRR communes.Footnote 53 This dynamic is far from limited to France. The Left in Britain, for example, has played a major role in the growing salience of residential constraints: by increasingly catering to wealthier urban voters, it has contributed to the decline of affordable public housing and has made cities unaffordable to lower-income citizens (Chou and Dancygier Reference Chou and Dancygier2021).

Hypothetically, mainstream parties could successfully capitalize on these issues in terms that have little to do with immigrants or other transnational actors.Footnote 54 However, their prioritization of voters in or near urban areas has left the door open for PRR parties to occupy and articulate localized grievances (like those linked to residential constraints) in exclusionary and reactionary terms and to attach them to the more general populist “left behind” rhetoric. RN’s recent political ads, such as “Against the abandonment of rurality, let’s defend our territories” or “Against the end of fiscal independence, let’s defend our local services” illustrate this focus well. This has been an explicit political strategy by the RN, particularly in areas like CM, where issues related to immigration or globalization are less salient, as also explained by a RN militant member:

RN member: “Well, at the national level, key party priorities are of course national identity and immigration. Here, in the Department, the priorities are not exactly the same. Key issues for voters here in CM are the centralization of the state, and the protection of rural areas and ‘rurality’ against urbanization and the increasing dominance of cities. Immigration or globalization are not big issues in the everyday life of citizens. The Department overall and cities like Saintes and La Rochelle, they are well-off… . But those who are less well-off, they are pushed further away, out of sight…. And even here in Saintes [second largest city], the big issue is that there are no jobs. People commute to La Rochelle [capital] because they cannot afford to live there.”Footnote 55

Conclusion

To deepen understanding of subnational variation in PRR support, this study advances a novel theory of residential constraints. The analyses of original, subnational-level data and individual-level qualitative evidence provide strong support for the hypothesized relationship: PRR is stronger in areas where access to economic opportunities and services is increasingly compromised and among residentially constrained individuals whose capacity to respond to this lack of access is limited.

Taken together, I contribute to and extend debates about PRR parties in several ways. First, by focusing on residential constraints, I build on, and move beyond, recent research that attributes PRR success to the economic geographies of deindustrialization, international trade shocks or manufacturing decline (e.g., Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Frieden Reference Frieden2018; Kurer Reference Kurer2020). Instead, I examine the political implications of economic restructuring through a different geopolitical lens and underscore the ways in which the agglomeration of employment opportunities and service delivery affects citizens’ lives, mobility, and choices outside these centers. In so doing, I show how the PRR’s appeal extends beyond areas that are objectively deprived, structurally poor, or hardest hit by globalization. Importantly, by calling attention to residential constraints, I bring to light relative economic conditions underpinning PRR support that the political behavior literature and PRR scholarship have thus far overlooked.

These findings accord with recent research on individual-level economic conditions and the contemporary PRR vote, which similarly calls attention to relative, rather than objective, economic dimensions (Burgoon et al. Reference Burgoon, van Noort, Rooduijn and Underhill2019; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017, Reference Gidron and Hall2020; Kurer Reference Kurer2020). This study adds new insights about how the cultural and economic determinants of PRR voting interact and generate geographic patterns of reactionary voting and attitudes. As such, it challenges prominent accounts of PRR voting as primarily a cultural backlash with little connection to economic conditions (e.g., Mutz Reference Mutz2018; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Rydgren Reference Rydgren2003). It also adds nuance to research underscoring self-selection and sorting as key to understanding geographic divides in anti-immigration attitudes. I demonstrate how limited mobility and lack of service provision can powerfully shape receptiveness to nativist, welfare chauvinistic PRR rhetoric in areas outside the more dynamic “cosmopolitan” cities. Thus, residential constraints can be an important mechanism that activates latent anti-immigration sentiments.

This study seeks to set the scene for future research into the political consequences of constrained mobility in postindustrial societies. The quantitative and qualitative analyses provide an important first step in identifying residential mobility and constraints as an increasingly important dimension of political behavior. As such, residential constraints raise several important questions for future research about how economic restructuring, globalization, and the resulting spatial inequalities in access to opportunities and services all structure political behavior and attitudes. Indeed, many scholars have also noted similar spatial divides in “radical” voting and attitudes across postindustrial societies (e.g., Ford and Jennings Reference Ford and Jennings2020; Golder Reference Golder2016; Maxwell Reference Maxwell2019). The broader changes related to the centralization of opportunities and services are likewise common to all postindustrial societies, suggesting that residential constraints may well strongly affect opportunities and political behavior far beyond the French context. Future research should also pay increased attention to how national policies and institutions exacerbate or alleviate residential mobility constraints, and how parties in other national contexts address these issues. At a time when the spatial polarization of party support and competition is increasing and mobility is declining, a systematic focus on the causes and consequences of residential choices and constraints offers important insights and future potential for both political economy and behavior scholarship.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S153759272100219X.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Kenneth Roberts, Sidney Tarrow, Christopher Way, Alexander Kuo, Nonna Mayer, Jan Rovny, Katherine Cramer, Peter Gourevitch, James Gimpel, David Pettinicchio, Alexandra Cirone, Jacob Swanson, and Michael Bernhard; four anonymous reviewers; and participants in workshops at Sciences Po Centre d’études europénnes, Cornell, Georgetown, University of Montréal, and University of Notre Dame’s Young Scholars in Social Movements in 2018–20 and APSA 2019 for their incredibly helpful and constructive comments. This research also benefited from generous funding from the Social Science Research Council, the Embassy of France in the United States, and the Thanks to Scandinavia Foundation.