Postsecondary archaeology and prehistory introductory courses typically do not center the potential of archaeology to improve human interests in the present and future. At predominantly white institutions (PWIs; Brown and Dancy Reference Brown and Dancy2010) in the United States, these courses are usually organized and presented to students in ways that perpetuate discrimination and social marginalization. This could be mitigated by “centering the margins,” in which we mean to center the needs and interests of marginalized peoples and archaeological stakeholders. Furthermore, we center marginalized theoretical paradigms that are taught as “alternative” rather than as valid and effective. We reveal the limitations and possibilities of archaeological knowledge production, encouraging students (and ourselves as educators and researchers) to ask, “Who benefits from archaeology, who is harmed, and how might we imagine a different way of studying and engaging with the past?”

Our work to revise our course at a predominantly white, small liberal arts college (SLAC) in the United States examined how archaeology can contribute to a more equitable society—which Ann Stahl recently described as an “effective archaeology” (Reference Stahl2020)—while integrating inclusive and justice-oriented pedagogical methods. This work follows calls to reimagine how we teach postsecondary archaeology (Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2004; Hutchings and La Salle Reference Hutchings and La Salle2014), but it is not unique to archaeological pedagogy (FitzPatrick Sifford and Cohen-Aponte Reference FitzPatrick Sifford and Cohen-Aponte2019; Harbin et al. Reference Harbin, Thurber and Bandy2019; Shelton Reference Shelton2020). Our approach builds on the possibilities that Maria Franklin outlined 15 years ago for historical archaeological research: “writing inclusive pasts, challenging traditional, dominant views of history, and wiping out divisive myths and stereotypes” (2005:194).

In this article, we (1) explain the limitations of introductory archaeology and prehistory courses, (2) demonstrate how we addressed these limitations by redesigning an introductory course at a US PWI SLAC, and (3) examine the redesign's impacts on students. In fall 2017, the authors taught a revised version of our introductory course, formerly titled Archaeology and Prehistory, which Fie has taught in the new format four times.Footnote 1 To demonstrate the impacts of these changes on our campus, we present results from an IRB-approved study of student reflections as well as enrollment trends over time by race and ethnicity.

Archaeology and prehistory courses typically focus on describing archaeological method and theory, discussing major trends over time, and depicting the human past chronologically or in order of sociopolitical complexity. To some, this may seem a neutral approach to representing the field and its study of the human past. This approach, however, fails to capture the diversity of epistemologies used in the field and may lead students to understand the past as a single story. It also risks reifying the myth of human societies as a teleological march from “savagery” toward “civilization.” Furthermore, survey courses are typically oriented around testing students’ capacities to memorize facts such as dates and culture names, even though such assessment methods may not be the most inclusive (Montenegro and Jankowski Reference Montenegro and Jankowski2017) or the most effective for capturing archaeology's social relevance.

Rich Hutchings and Marina La Salle (Reference Hutchings and La Salle2014) recently called for an anti-colonial approach to teaching archaeology, arguing that the colonialist version of teaching archaeology must be rectified. Following Tuck and Yang (Reference Tuck and Yang2012), Dei and Asgharzadeh (Reference Dei and Asgharzadeh2001), and Mahuika (Reference Mahuika2008), Hutchings and La Salle term their approach “anti-colonial” rather than “decolonial” to go beyond the mere recognition of colonized ways of knowing and instead take an “explicitly political stance of resistance to all forms of colonialism” (Hutchings and La Salle Reference Hutchings and La Salle2014:40). The anti-colonial approach is also methodologically and theoretically heterogeneous, but particularly centers anti-racist, anti-oppressive, Indigenous, feminist, queer, and other critical and activist paradigms. The changes made by Hutchings and La Salle (Reference Hutchings and La Salle2014:30) were for courses of 75 to 350 students, whereas the classes we taught have a 30-student enrollment maximum. This enrollment difference allowed us to incorporate different kinds of assignments and ways of learning (particularly using principles of universal design for learning [UDL]), which we detail below.

Maxine Oland (Reference Oland2020) recently published an urgently needed guide on teaching archaeology through inclusive pedagogy. The changes we propose are similar in calling for greater attention to the pluralistic needs of students and in designing courses that incorporate UDL principles. In the UDL framework, instructors change the environment (rather than the learner) in order to support students’ growth as “expert learners” and help them be “purposeful and motivated, resourceful and knowledgeable, and strategic and goal driven” (CAST 2018a). Oland includes actionable suggestions for creating a safe and welcoming environment, offering students more agency, and generating meaningful, active learning experiences. In this study, we advocate for deeper structural changes that are particular to the epistemological problems of archaeology, including reassessing learning goals, text choices, case studies, and the ways we present the potential future of the discipline to students. We also offer evidence for the effects of these changes.

WHY REIMAGINE THE INTRODUCTORY ARCHAEOLOGY COURSE?

The purpose of teaching archaeology is not simply to convey the contours of the past but also to benefit people in the present and future (e.g., McGuire Reference McGuire2008; Merriman Reference Merriman2004; Richardson and Almansa-Sánchez Reference Richardson and Almansa-Sánchez2015; Supernant et al. Reference Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020). The study of the past is not neutral: some individuals, communities, and populations benefit from learning about archaeology (e.g., Battle-Baptiste Reference Battle-Baptiste, Ogundiran and Falola2007; Franklin and Lee Reference Franklin and Lee2020; Franklin and Paynter Reference Franklin, Paynter, Ashmore, Lippert and Mills2010; Lane Reference Lane2015; Logan Reference Logan2016; Sandweiss and Kelley Reference Sandweiss and Kelley2012; Southwell-Wright Reference Southwell-Wright, Wappett and Arndt2013; Stump Reference Stump, Isendahl and Stump2019; Thiaw Reference Thiaw, Okamura and Matsuda2011), whereas others are harmed (e.g., Arnold Reference Arnold1990; Atalay Reference Atalay2006; Deloria Reference Deloria1997; Watkins Reference Watkins, Phillips and Allen2010). Archaeological representations of the past, whether in an undergraduate course or elsewhere, masquerade as objectively truthful accounts. Our understanding of the archaeological record, however, is biased toward those places where research has been conducted, what kinds of questions have been asked, and whose experience and worldview are given primacy. Scientific epistemologies—including archaeological ways of knowing—are often considered natural or neutral, yet a long tradition of feminist critique demonstrates that this is not the case (Haraway Reference Haraway1988; TallBear Reference TallBear2014). Educators may value the use of archaeology to address social conditions in the present, but typical ways of teaching archaeology have limited capacity to explain contemporary inequities due to biases in how we know what we (think we) know and how we present it to others.

Enrollment of students of color and students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds is low in archaeology courses (Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2004:295). This trend continues into the professional ranks and every aspect of knowledge production in the discipline (Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2019, Reference Heath-Stout2020; Heath-Stout and Hannigan Reference Heath-Stout and Hannigan2020; White and Draycott Reference White and Draycott2020), especially in the underrepresentation of Black archaeologists (Franklin Reference Franklin1997; Odewale et al. Reference Odewale, Dunnavant, Flewellen and Jones2018). One factor affecting racialized and socioeconomic disparities may be whether students see their identities and their interests represented in both the stories archaeologists tell about the past and the people who get to tell those stories (i.e., whose scholarship they read).

The Society of Black Archaeologists, for example, was established in 2011. Part of its mission is to promote the work of Black archaeologists (SBA 2020a). In June 2020, over 2,600 people registered for the SBA panel discussion titled “Archaeology in the Time of Black Lives Matter” (SBA 2020b). Although there is newly urgent (yet overdue) interest in these themes within the discipline, archaeologists have long called for multivocality and a greater diversity of perspectives (Agbe-Davies Reference Agbe-Davies2002; Atalay Reference Atalay, Habu, Fawcett and Matsunaga2008; Bardolph Reference Bardolph2014; Gnecco Reference Gnecco1999; Perry Reference Perry2019), and they have found the discipline wanting (Conkey Reference Conkey2007; Fulkerson and Tushingham Reference Fulkerson and Tushingham2019; Morgan Reference Morgan2019). The voices and perspectives of a few have been made dominant partly through what instructors and textbook authors tend to present as normative archaeological theory. Moreover, Indigenous knowledge and archaeological theories informed by Black Marxist and Black feminist thought are briefly mentioned or ignored within classroom readings and discussions.

In a study of multi-edition archaeology textbooks, R. Lee Lyman found that theories presented in textbooks “reflect the state of the art in a discipline at the time of . . . publication” but that “these volumes . . . do not provide nuanced and thorough reflections of disciplinary history” (Reference Lyman2010:1). Yet, rather than merely lacking in nuance, textbooks present the state of the discipline according to those already afforded the most prominent platforms in the field. These platforms disproportionately elevate white, middle-class men from elite universities (Conkey Reference Conkey2007; Fulkerson and Tushingham Reference Fulkerson and Tushingham2019). As Margaret Conkey points out in a survey of archaeological theory readers, “big scale processes” such as settlement patterns and technology are given prominence (Reference Conkey2007:291; see also Cobb Reference Cobb2014) and “Anglo-American archaeology is still nearly a completely white and middle-class enterprise” (Conkey Reference Chazan2007:304). In both textbooks and theory manuals, feminist and critical theories are treated as marginal and excluded from mainstream accounts of dominant theoretical paradigms. They may be cast as unscientific and lacking in objectivity. In contrast, archaeologists writing textbooks consider more processually aligned theories essential. Hutchings and La Salle (Reference Hutchings and La Salle2014:30) describe this phenomenon in newer textbooks as well. For example, the fourth edition of Michael Chazan's (Reference Chazan2017) World Prehistory and Archaeology: Pathways through Time lists post-processual archaeology as “Alternative Perspectives,” and it details gender, agency, and Indigenous perspectives in a section titled “Branching Out” (Supplemental Table 1). In some textbooks, theories not aligned with processualism are presented in sidebars rather than paragraphed prose, if mentioned at all.

Some theories are indeed cited more often than others, and textbooks are simplified versions of approaches to the past. However, the presentation of certain theories as dominant and essential perpetuates the marginalization of particular ways of knowing. Archaeologists have the responsibility to engage multiple perspectives on the past to forge better futures for more humans. As Colleen Morgan, in reference to the limited representation of racial and gender identities in archaeology courses at the University of York, remarks,

the canon is archaeology's own creation story, repeated and handed down through successive generations of scholars. . . . The first year of undergraduate education is a critical time to form the archaeological canon that students will take forward and replicate, or repudiate in time [Reference Morgan2019:10].

We must challenge normative archaeology by “unsilencing” marginalized narratives. The organization of textbook units and chapters warrant further critical consideration (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Archaeology courses and their attendant textbooks are typically organized in a seemingly contrived order of “primitive” to “civilized,” whether by region or sociopolitical complexity: they progress from hominins to bands, tribes, chiefdoms, states, and empires (Hutchings and La Salle Reference Hutchings and La Salle2014:30). Whether intended or not, these seemingly naturalized renditions of progress narratives reify myths about inevitable marches toward civilization, and they promote an imagined social distance between egalitarian and nonagricultural societies and the agricultural empires taught at the end of the semester. Some societies are treated as exceptional in textbooks—where states and empires did not develop, where states developed within regions dominated by nonstate societies, and where sociopolitical complexity developed without agriculture. The result is a narrative arc that reinforces stereotypes and marginalizes the rest.

ADDRESSING LIMITATIONS THROUGH COURSE REVISION

Revising our introductory archaeology course was informed by larger pedagogical theories as well as critiques particular to archaeological ways of knowing. First, we subscribe to a model of learning-focused course design (also known as backward-integrated design)—crafting courses based on what one expects students to be able to do by the end of a course rather than being governed by content goals (Grunert O'Brien et al. Reference Grunert O'Brien, Millis and Cohen2008). In this way, we moved away from a content-focused, traditional syllabus of geographic and/or neo-evolutionary themes from “primitive forward.” Instead, we planned the course around values and skills that we want students to hold at the end of the semester and even years later. In this case, we introduced them to archaeological theory and methods as well as the human past, but we also prepared them to analyze evidence about humans critically and apply lessons from the past. We built analytical capacities that students could take with them beyond the classroom and beyond archaeology.

We also subscribe to the tenets of critical pedagogy and democratic, multidirectional learning espoused by both bell hooks (Reference hooks1994) and Paulo Freire (Reference Freire1985), which involve de-centering the instructor as an all-knowing orator. We reject the idea that students are empty vessels to be filled with unquestionably neutral knowledge. We are also influenced by the pedagogy of kindness, which emphasizes compassion and understanding of students’ needs rather than positioning students as antagonists to instructors (Denial Reference Denial2019). To integrate these pedagogies, and to respond to the call to action by Hutchings and La Salle (Reference Hutchings and La Salle2014), we shifted which voices were given prominence, what the course's narrative arc was, how the past was linked to a better human future, and how students could demonstrate/develop their place in archaeological knowledge production.

The Course Prior to Revision

At our U.S. PWI SLAC, the introductory archaeology course was originally designed around archaeological method and theory coupled with “prehistory.” Given that it is an introductory survey course, we enroll around 30 students per section. Enrollees include intended and declared anthropology majors as well as students fulfilling general education requirements who are not particularly interested in anthropology. Although we sometimes have an undergraduate teaching assistant, there are no breakout sections for labs or discussion.

Prior to fall 2017, we taught slide-based lectures and assigned a common prehistory textbook. Sometimes, we also assigned Kenneth Feder's Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology (Reference Feder2017), which students used to develop group presentations on epistemology and public knowledge production. The course began with an introduction to archaeological methods, including the formulation of research questions, field strategies, excavation methods, and laboratory analyses. The majority of the semester covered the “prehistory” archaeologists study. Most class periods consisted of presentations on how different approaches and methods are used to understand the major cultural developments in geographic regions, from early tool-user hominids in Africa through complex state developments in Eurasia and the Americas. Although discussion was limited, we often took students into the Logan Museum of Anthropology to engage with course theme–related objects and exhibits. Assessment of student learning was primarily short-answer tests.

The Revision Process

Even though the course textbook, lectures, and lesson plans were regularly updated, we recognized the need for major revision. Students were primarily drawn to the course to learn about pyramids and Vikings. Some cultural anthropology–oriented majors merely participated unenthusiastically to meet requirements. Occasionally, Fie explored reenvisioning the course, but the lack of an alternative textbook posed a significant challenge.

In spring 2017, Fie collaborated with independent-study students to reimagine the course so that it would focus on relevant and applied archaeologies, including themes such as identity, power and privilege, conflict, sustainability, and climate change; explore these themes as recurring issues addressed in different ways by societies in different places and times; and illustrate how archaeologists identify and make sense of how and why societies differ in those ways. Fie, along with Agnew and five other students, identified new course readings (some that were accessible to nonexperts, along with others written for archaeologists) and developed supplementary lecture content, discussions, and activities. They identified sources from a plurality of perspectives and curated a list for instructors to choose from as they crafted a syllabus. In summer 2017, Quave revised the materials and pedagogical approach through the Mellon Foundation–funded “Decolonizing Pedagogies” workshop at Beloit College. Subsequently, all four authors revisited the objectives for the new course and made substantial course revisions as outlined in Tables 1 and 2 (Supplemental Text 1). During the fall 2017 semester, we met weekly to discuss and recalibrate according to student engagement with the material.

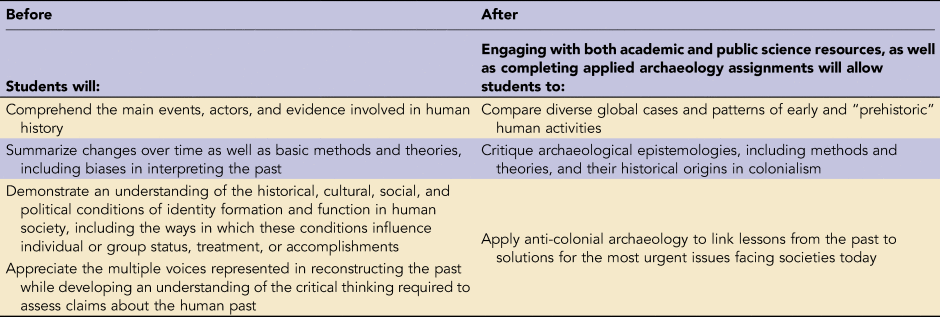

Table 1. Learning Objectives of the Course before and after Revision.

Table 2. General Syllabus Schedule before and after Course Revision.

The Revised Course

The revisions to the course re-centered students’ perceptions of authoritative knowledge and included case studies and theoretical and methodological perspectives that better represent what applied archaeologists hope that the discipline will accomplish. Our approach emphasizes critical assessment of how archaeologists know what they know, whose voices are centered, and how knowledge is constructed and disseminated (Harbin et al. Reference Harbin, Thurber and Bandy2019; Kishimoto Reference Kishimoto2018). These changes are not particular to archaeology, but they are worth mentioning because they shaped all pedagogical decisions. In this section, we describe specific pedagogical methods and examples for meeting the goals laid out in the first half of this article.

How Did We De-center the Instructor?

Following the tenets of democratic and participatory/experiential pedagogies (Carlson and Apple Reference Carlson, Apple, Carlson and Apple2018; Freeman et al. Reference Freeman, Eddy, McDonough, Smith, Okoroafor, Jordt and Wenderoth2014; Freire Reference Freire1985), we shifted the focus away from the instructor as unquestioned academic authority. Instead, we developed our course around student engagement and multidirectional learning: students are collaborators in the production of knowledge within the course and must acknowledge the way their positionality shapes their understanding of course material (Takacs Reference Takacs2003). Rather than emphasize instructor-to-student information transfer through lectures as we had before, we included short lectures with each unit to introduce a theme and human problem, but students spent the majority of class time in active learning. Furthermore, we encouraged students to take our classroom dialogues beyond the course, often asking them to imagine that they were at a family meal explaining difficult course concepts to nonexperts. In this way, we emphasized the application of classroom knowledge production beyond class walls.

How Did We Ensure Pluralistic Perspectives on the Past?

Students largely trust textbooks as authoritative and assume that the writers are removed from the content of their writing (Olson Reference Olson1980). Similarly, students are usually detached from the process of course design, and they assume that instructors require the most canonical readings beyond the textbook. Of course, the canon is constructed through citation practices within a discipline rather than being natural or based on some objective intellectual merit. As instructors, we must take responsibility for constructing the perceived canon in the classroom (and for emphasizing that whom we read and whom we cite are decisions shaped by our worldviews and priorities). Fostering equitable citation practices is urgent (Edmonds Reference Edmonds2019; Mott and Cockayne Reference Mott and Cockayne2017). For example, the “Cite Black Women” movement, begun in November 2017, called attention to the need to center the knowledge production of marginalized scholars, specifically Black women. We replaced the large and expensive introductory textbook; brought case studies and theories by underrepresented scholars to the fore; included more “nonacademic” sources written by other types of experts; and positioned Black, Indigenous, and critical ontologies alongside positivist ways of knowing to demonstrate the plurality of theoretical approaches.

We realize that many university programs require instructors to use a survey textbook for introductory courses. For our revised course, we adopted Paul Bahn's Archaeology: A Very Short Introduction (Reference Bahn2012) to provide one of many perspectives. Bahn's text does two important jobs: (1) at $12, it is one-tenth the cost of a typical introductory archaeology text, which makes the course more accessible; and (2) it precludes the unwelcome role of a single, authoritative source written by one or two archaeologists. We use it to discuss text authority and assumptions about textbooks, jumping off from Lyman's (Reference Lyman2010) study. The chapters center on method-driven topics, but they also address archaeologists’ responsibilities to the public and heritage stewardship. The brevity of Bahn's volume (just 100 pages) prompts students to ask, “What is missing?”

We also chose open-source readings in addition to institutionally accessed readings. Including think-pieces and blogs (e.g., Abu Hadal Reference Abu Hadal2013; Black Trowel Collective 2016) alongside academic journal articles and chapters helped students not only see the various venues in which archaeological knowledge is disseminated but also think about who benefits from and who is harmed by archaeological reconstructions of the past. And starting the semester with different perspectives from scholarly and nonacademic texts showed the value of diverse ways of knowing the past while also providing an opportunity to question the supremacy of Eurocentric scientific traditions. In teaching archaeological theory, Black feminist archaeology (Battle-Baptiste Reference Battle-Baptiste2011) was one of the first theoretical paradigms with which students reconstructed the past. In introducing the humanistic and scientific tendencies of archaeologists, we asked students to read case studies on the Pleistocene origins of the first Americans that offer pluralistic views in science (Deloria Reference Deloria1997; Grayson and Meltzer Reference Grayson and Meltzer2003).

How Did We Center Ethical Concerns?

In order to center Indigenous and anti-racist ontologies, we eliminated the terms “prehistory” and “New World,” and we drew attention to the problem with using those terms and others such as “Classic” and “Horizon.” The first day of classes, we asked students where they had heard these terms and what they meant in order to preempt a discussion of the harm done by their uncritical use. Students examined how “New World” and “Old World” privilege the “discovery” narrative of European exploration and fail to recognize the deep histories of peoples in the Americas with their own cultural trajectories, and they came to realize that “prehistory” is a disparagingly primitivizing term. Although “prehistory” is often used uncritically, it warrants scrutiny due to the fact that it arbitrarily separates societies interpreted to be “preliterate” from those with surviving written records (deemed readable by outsiders). The label others, marginalizes, and primitivizes societies that have largely been subjected to colonial rule, thereby reifying global inequalities. Having this discussion in the first week gave space for students to see how seemingly minor word choices can have major harmful impacts.

In previous versions of the class, we taught ethics most directly in the final unit of the semester (although we taught occasionally with Feder's Frauds, Myths, and Mysteries [Reference Feder2017], which prompted additional discussions of ethics throughout). In the revised course, however, ethical questions were posed from the start of each unit. Students were iteratively prompted to ask and answer, “Who is helped and who is harmed by the reconstruction of the archaeological past?” Class discussions and assignments focused on how producing and consuming archaeological knowledge requires ethical approaches. For example, when teaching the scientific method, we showed an episode of Ancient Aliens in order to examine how an illusion of objectivity was constructed to perpetuate racist myths (Bond Reference Bond2018). Throughout the semester, we asked students to consider how they reify marginalizing narratives about the past through their consumption choices and how to mitigate or avoid the impacts of those decisions.

How Did We Overcome Progress Myths?

Teaching the past chronologically and/or following a neo-evolutionary progression of prehumans to empires positions Euro-American and white perspectives as neutral ways of knowing and reproduces the harmful assumptions of a lockstep march toward civilization. In this way, any societies not “progressing” are implicitly represented as backward. To avoid such teleological ways of knowing, we organized the course conceptually along themes of social relevance. Instead of organizing by geographic boundaries, chronological units, or evolutionary progress, we chose problems to investigate and case studies to illustrate them (Tables 1 and 2). Importantly, we explained to students why we avoided the neo-evolutionary organization for the course. We did not erase regional sociopolitical trajectories, but we did not present a single trajectory as normative. The themes were wide-ranging and timely. For example, a unit on migration, climate change, sustainability, and health included case studies such as Irish immigrant acculturation and respectability politics, biocultural reconstructions of dairy consumption in Neolithic Central Europe, Neandertals and disability, Maya responses to climate change, Inka pastoralism, archaeologies of fire management, historical food insecurity in Ghana, and the Norse collapse in Greenland.

How Did We Orient the Past toward the Future?

Another guiding principle of the course was how both the past and explanations of it are political. We featured case studies on the ways archaeologists have studied monuments, their destruction, and the value of public memory. We discussed how cross-cultural understandings of monument destruction in the past could be applied to decisions about Confederate monuments’ futures and what was at stake for human well-being (Carter Reference Carter2018). We also critically considered “looting” and unauthorized excavations by examining ethnographic studies of artifact destruction and collection in different regions and times (Dunn Reference Dunn, Card and Anderson2016; Hart and Chilton Reference Hart and Chilton2015). Differentiating why some types of nonscientific excavations are considered illegal or immoral gave students an opportunity to examine colonialist attitudes about heritage conservation. Supplemental Text 1 expands on more themes and case studies, with lesson planning notes for instructors.

How Were Assessments of Archaeological Knowledge Made Accessible and Relevant?

Using UDL principles and active learning, we created assessments that prioritized garnering the past in service to a better future. In the same way that Oland (Reference Oland2020) made changes to her introductory archaeology course, we designed assignments for diverse learning needs with multiple ways of consuming course materials and of producing course knowledge for assessment of student learning (CAST 2018b). This meant that assignments went beyond writing prose—we incorporated presentations, listening exercises, and multimedia/multimodal projects (e.g., blogging [Figure 1]). Learning was enhanced by technology, it was collaborative and cooperative, and it was linked to real-world scenarios. Students were provided with rubrics; activity formats were varied; student diversity was respected; and we used frequent, scaffolded assessments (Boothe et al. Reference Boothe, Lohmann, Donnell and Hall2018:Table 1). We offer details on a selection of assessments in our Supplemental Materials.

Figure 1. Screenshot from the student-reviewed and student-written course blog site Past Forward.

Students critically interrogated archaeological ways of knowing through a simulated excavation. A rejection of the “sandbox approach,” this alternative method by Paul Thistle (Reference Thistle2012) uses paper units and late twentieth-century artifacts, as well as drawn features, to simulate spatial relationships that are to be carefully and accurately recorded. Students must collaborate to properly contextualize individual units that are compared across the simulated site. Upon completion of a collaborative site map, students wrote reports in which they were required to generate hypotheses, reflect on how their positionality shapes their epistemology (Takacs Reference Takacs2003), and examine their biases in interpreting the past through the material record (Supplemental Text 2). They also had to discuss to whom this past is relevant as well as who gets to decide where to do research and how, while considering the findings of the simulated excavation in comparison with excavations at a historic site on campus (Starck and Green Reference Starck and Green2014).

Assignments were designed to call attention to issues of access to the past. Archaeology's visual emphasis, particularly when teaching in the slide-lecture format, comes at the cost of accessibility for visually impaired students and stakeholders. One proposed way to mitigate this problem is 3D printing (Hugo Reference Hugo2017). To supplement our teaching collection of artifacts and reproductions, we brought printed objects into the classroom; 3D printing could be used at institutions that do not have direct access to collections, that have fragile or sensitive collections, or that have enrollments that are too high to mitigate risks. With concern for visual accessibility in mind, we designed a visual/tactile sensory lab with anthropology museum staff (Supplemental Text 3). Additional learning goals were to examine how heritage and artifacts are made accessible to particular audiences and to critique how anthropology and art museums foster an exoticizing gaze of the “other” (Hodge Reference Hodge2018). In the lab, objects were placed on tables and covered with cloth. Students interacted with the objects either with their eyes closed, by feeling underneath the cloths, or by only experiencing the object visually. Students then switched roles and interacted with a different set of objects. Relying on touch without sight challenged biases of aesthetic connections to cultural material and raised questions of producers’ intent. Variations of this activity could be conducted with household and/or classroom items. The goal is to challenge people's preconceptions of objects and their use and to enable people to experience multiple ways of interacting with the material record.

Other assignments focused on addressing exclusionary or limited ways of representing the past (Supplemental Text 4). Students applied theoretical and methodological concepts from Whitney Battle-Baptiste's Black Feminist Archaeology (Reference Battle-Baptiste2011) to virtual representation of Andrew Jackson's Hermitage. They reviewed the Hermitage website to identify how past people were represented. Students then explored the Digital Archaeological Archive of Comparative Slavery (DAACS) resources from the Hermitage (specifically, the Triplex to see materials recovered from within the living quarters of the enslaved). Students analyzed whose past was represented as well as whether the Hermitage pages muted the experiences of enslaved peoples—and if so, which ones. They were prompted to discuss lived versus imagined pasts, who has the right to excavate a plantation, and whether the Hermitage should serve as a tourist destination, much less a special events venue (Mullins Reference Mullins2017). Subsequently, students chose an artifact from DAACS and rewrote a section of the Hermitage website to include the artifact and to center the experiences of the enslaved truthfully.

Another assignment analyzed how multiple stakeholders experience the sacred burial and effigy mounds on the Beloit College campus. Currently, faculty and students work inside and outside of the classroom to acknowledge Indigenous land and heritage, as well as the resulting institutional harm that comes with building a college atop a mound group. In this course, we have students explore the campus and the surrounding areas to identify and assess the conditions of the Beloit College Mound Group. As a result, students learn about Native earthworks and related responsibilities for nondescendant stewards on Native lands. When possible, Ho-Chunk tribal members participate in conversation with the students about their lived experiences today. These conversations underscore the experiences of Native communities and the reasons for which their priorities and concerns often do not align with those of non-Native archaeologists.

A final project—the “anti-colonial” archaeology textbook—bound archaeological knowledge-making to current social concerns. We made this accessible by offering a menu of modalities with which students convey their knowledge: prose, infographics, animations, podcasts, or other media. Students collaborated in teams to create multimedia chapters for the textbook they would want to read in an introductory archaeology course following our pedagogical principles (Supplemental Text 5).

OUTCOMES OF REVISING THE INTRODUCTORY ARCHAEOLOGY COURSE

Students Reflect on Outcomes

To assess the outcomes of these changes to our course, Quave assigned reflective essays, following Hutchings and La Salle (Reference Hutchings and La Salle2014:49). Students answered the same questions about archaeology at the beginning and end of the semester to assess if/how their understanding of archaeology's relevance had changed. With IRB approval, Quave obtained informed consent from 16 of 24 students from a fall 2017 section for textual analysis of their pre-course and post-course essays. We focus our analysis on two of the questions (Supplemental Text 6):

• Whom does archaeology benefit and whom does it harm?

• How, if at all, do you see your interests reflected in the practice and profession of archaeology?

Students wrote their pre-course assessments after we had discussed the problems of terms such as “New World” and “prehistory,” which likely had an impact on some views. We believe, however, that these assessments reveal how students moved from an initial, superficial understanding of archaeology as being both beneficial and harmful to living people (as 13 of 16 students stated in the pre-term assessment)Footnote 2 to a post-term understanding of the complex ways that archaeology is beneficial and harmful to different kinds of stakeholders in various situations. We are not suggesting that students were ignorant of the field at the start of term. In fact, many were anthropology majors who already had a passing understanding of the discipline. For example, one student wrote, “By studying artifacts and other physical remains, it can give clues not only to the past but to our present and our future.” Instead, we hypothesized that they would—by semester's end—be able to articulate the challenges and possibilities of the field more confidently and with greater nuance, and that they would become oriented toward solutions.

In the pre-term assessment, the majority of students stated that archaeology could be both harmful and beneficial, and there were some patterns in their descriptions of the impacts. Several mentioned the harmful effects on Indigenous peoples, especially when sacred objects are decontextualized in museums and when researchers enter into (formerly) colonized places to conduct fieldwork without community collaboration. A few students started the semester with a bleak outlook on archaeology. Here is one example from those students:

In the past, archaeology has always benefited white men, the conquerors and imperialists, and was unfair to the native populations of many areas of the world. Archaeology is similar to other branches of anthropology which have been used to form hierarchies and help with the colonization and manipulation of certain groups.

Another theme from the pre-term assessment was a nostalgia derived from associating archaeology with childhood memories of visiting ancient sites and museums or seeing artifacts on family farms. Even among students who critiqued the colonial roots of the discipline, there were nostalgic responses to the prompts (with emphasis on visiting monumental sites or collecting).

In the post-term assessments, we did find shifts in students’ understanding. They explained the effects of archaeology on different stakeholders with greater nuance. They described the impossibility of archaeology being done without bias, and they focused on the unintended impacts on descendant communities’ well-being, especially related to human remains and sacred objects. Many (12/16) responded that some archaeologists are aware of the ways the discipline is harmful and are working to mitigate the negative impacts on stakeholders.

Although some students began the semester indicating that they saw archaeology as irredeemably harmful, by the end of the semester, those same students articulated ways of lessening harmful impacts. They wrote that some descendant and stakeholder communities that are socially marginalized can reap benefits from archaeological research when it is undertaken in ways that de-center normative viewpoints or promote self-determination (9/16). They had not written in those ways in the pre-term assessments. One post-term assessment stated, “If we try to look through the past with different theoretical lenses that are not centering our own privilege and our own culture, we may come up with different answers. We can use archaeology to make space for those who are not given space currently.” In contrast, the one student who explicitly stated in the pre-term assessment that they did not see archaeology as harmful offered several examples in the post-term assessment about the potential for harm.

The overall takeaway from the student responses was that the course impacted their understanding in productive ways. In describing how archaeology specifically benefits people, students were able to articulate lessons from the past for climate-change responses, sustainability, identity and well-being. Two quotes from the post-term assessments highlight the ways the course helped students question what they thought they already knew and value the revisions we made:

Student 1: As someone who cares deeply about social justice and the inequities that I see and experience . . . I see it as my job to use archaeology as a tool to reorient my understanding of the world. Much of what I was taught as fact throughout my schooling is nothing more than interpretation, full of biases and inaccuracies. This course has given me the tools to take nothing I learn for granted, to humble and silence my voice in respect of those around me, and how to take pride in confronting my own preconceived notions and biases, both conscious and not.

Student 2: I feel like what I've done in this class is more important than knowing the exact timeline of human existence.

Pursuant to the revisions made to the course, the archaeology introduction survey became an elective for students majoring in the college's Critical Identity Studies program (CRIS). An interdisciplinary, intersectional, and social justice–oriented program, CRIS investigates “how gender, race, ethnicity, socio-economic class, sexuality, dis/ability, nation, non/religiosity, and region shape identities” (Beloit College 2019a). The inclusion of the archaeology course in the CRIS curriculum is a recognition that learning about the past is a way to understand and improve society's present and future.

Continued research on student reflections should include reporting on demographics in order to cross-reference student responses to the course with their social identities. At this point, we can report on some aspects of the enrollment trends that resulted from the course revision.

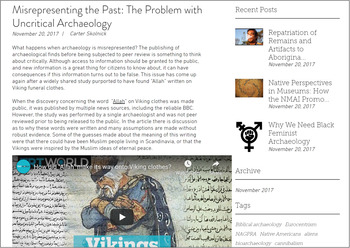

Quantifiable Outcomes in Enrollment

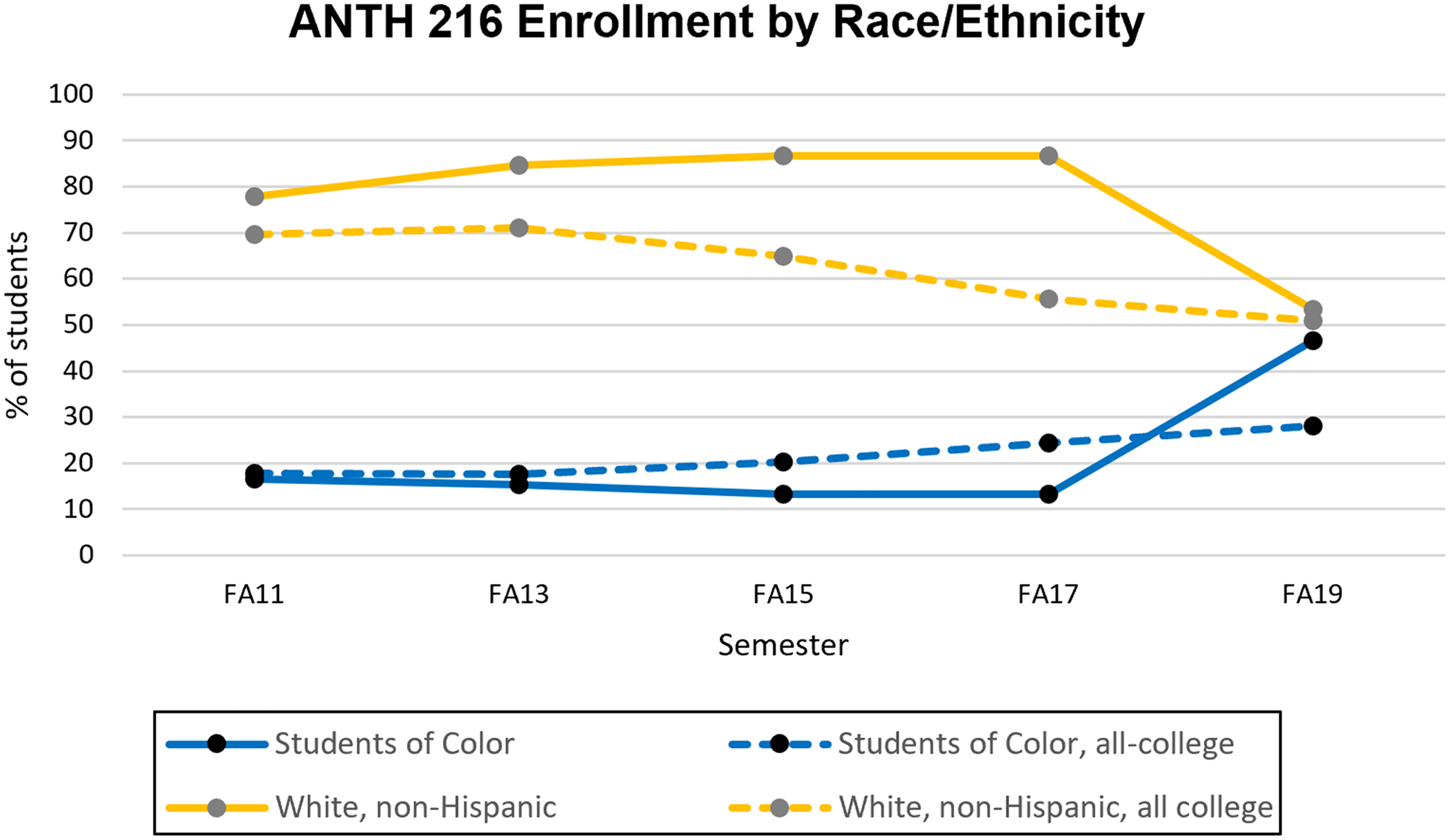

Adoption of the new curriculum shifted the racial demographics of which students enrolled not only in the introductory course (Supplemental Table 3) but also in the elective follow-up Principles of Archaeology course (Supplemental Table 4). Although there are many social identities systemically excluded from archaeology, these enrollment data allow us to quantify transitions in race and ethnicity for now.Footnote 3 The new curriculum was adopted in fall 2017 and taught under the previous title and course description. This means that students who enrolled in the fall 2017 course expected to encounter the traditional content and structure. The new course title and description appeared in time for spring 2018 registration. Beginning in spring and fall 2019, students could enroll in a cross-listed section in Critical Identity Studies (CRIS) as an elective for that major. The enrollment data suggest that the new content and approach, bolstered by inclusion within the CRIS curriculum, disrupted the previous demographic makeup of the course. In 2018, following the course revision, we saw an increase in the proportion of students of color (all race and ethnic identities other than white, non-Hispanic) above that found prior to the revision (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Enrollment trends for ANTH 110 by race and ethnicity (simplified as white, non-Hispanic versus students of color) from fall 2014 to fall 2019 (n = 362). The light gray area is when the revised course was introduced, and the dark gray area is when the course was cross-listed with Critical Identity Studies (CRIS).

For the last two years, however, the trajectory differs in the spring semester as opposed to the fall semester. We attribute this to the current catalog description, which does not adequately capture the anti-colonial approach taken since fall 2017. It reads:

Archaeology: Lessons from the Past. All human societies face challenges, including those relating to power, identity, conflict, health, sustainability, and climate change. Using scientific and humanistic methods and theories, archaeology provides unique lessons for addressing such issues in the present and the future. In this course, we begin with an introduction to basic archaeological methods and theories, as well as the major trends of prehistory. Throughout the remainder of the class, we analyze case studies to better understand how societies succeed or fail when faced with specific challenges within different social, political, and environmental contexts [Beloit College 2019b].

Students are more likely to hear about the course's anti-colonial position through word of mouth on a SLAC campus. Because so many first-year students enroll based only on the catalog description, the enrollment demographics appear different in the fall as opposed to the spring, when more students of color tend to enroll.

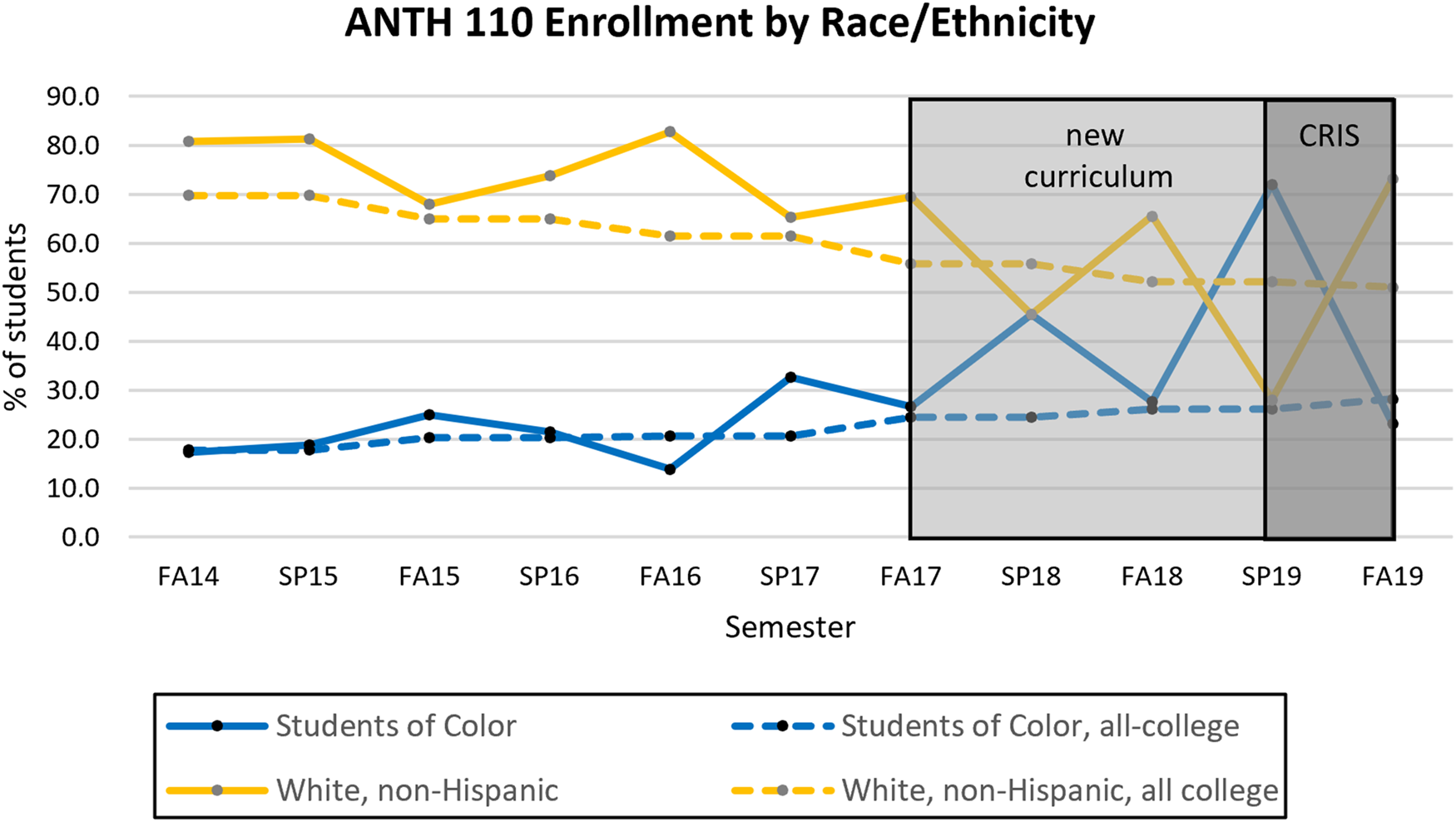

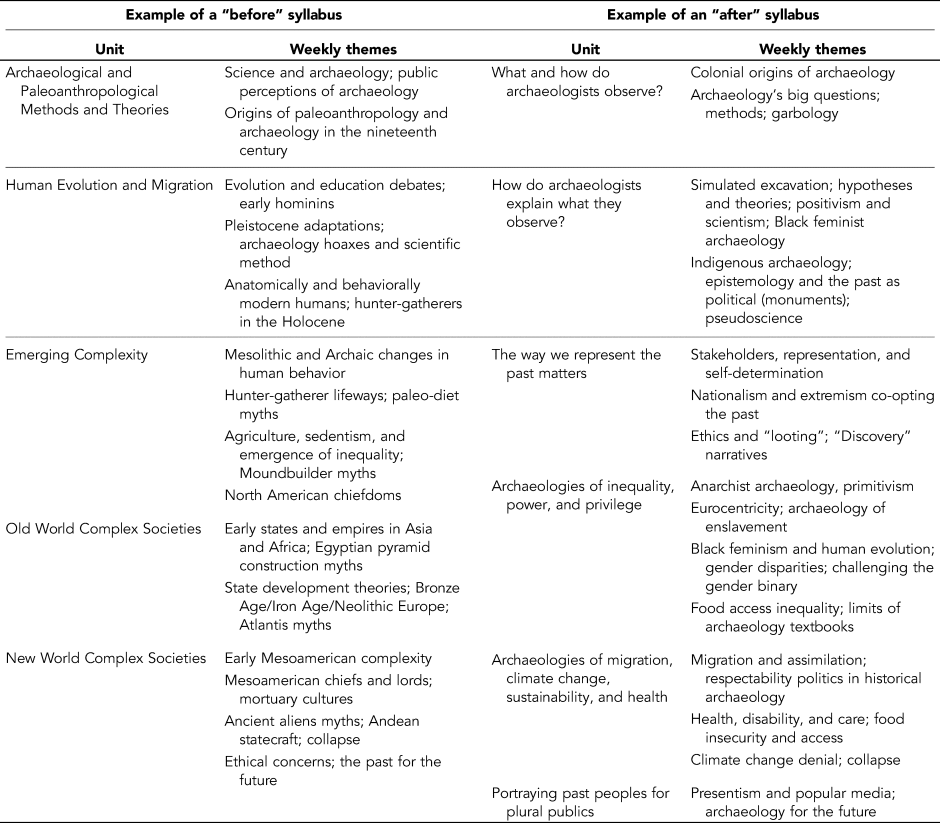

The impact of the course revision is more apparent down the line in the mid-level methods course, Principles of Archaeology. This course involves active learning, including small-scale excavations on campus and class projects directed at preserving and educating the community about the importance of the campus mounds. Enrollment by students of color, however, historically sat well below the college average, but this trend shifted in fall 2019. Most of the students in the fall 2019 ANTH 216 class were introduced to archaeology through the new ANTH 110 curriculum and, at 46.7%, the Principles of Archaeology course enrolled students of color well above the college average of 28.2% (Figure 3). Principles of Archaeology is not a required course in either the general college curriculum or the major/minor, so students choosing to continue to the intermediate level in the subdiscipline is notable (it is not just that the pipeline demographics shifted at the college but also that students of color chose to continue learning in the archaeology subfield). We will continue to assess these enrollment trajectories, and we hope to collaborate with other campuses to implement these reforms for a more inclusive and representative archaeology.

Figure 3. Enrollment trends for ANTH 216, the mid-level methods course in archaeology, by race and ethnicity from fall 2011 to fall 2019 (n = 76). Fall 2019 was the first time students enrolled after the revision of the introductory course.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study of the processes and impacts of revising our introductory archaeology course, we demonstrate that there is an urgent need to reimagine how we teach postsecondary archaeology. This urgency is due to the exclusionary and marginalizing character of much archaeological work and archaeological knowledge production, both historically and currently. The campus on which this course was developed is the ancestral territory of Indigenous peoples, made visible by the presence of 20 conical, linear, and animal effigy mounds that sit between academic buildings. As settlers on this Indigenous land, and in a country built by enslaved Africans, we have a responsibility to actively address past and present structural violence.

In teaching archaeology and thereby producing archaeological knowledge, we advocate for re-centering the archaeological curriculum by rejecting traditional-textbook-guided ways of presenting the study of the past. We show how harnessing the methods, theories, and case studies already in the academic and nonacademic literature can generate a classroom that better meets the needs of all learners. Furthermore, we find that this way of teaching archaeology facilitates greater diversity and increases diversity in ways of knowing, which could lead to greater equity and justice within the profession. Revising the introductory archaeology course is one of many changes that must be made in the discipline.

The values that guided our work here are not novel. We build on the aspirations others share for an “effective archaeology” (Stahl Reference Stahl2020). Although we did not use the Society for American Archaeology's Principles for Curricular Reform (Bender Reference Bender, Bender and Smith2000) in our course design, we find that we are closely aligned with them. Drafted at the turn of this century, they emphasize archaeology as a nonrenewable resource to be stewarded in consultation with “various publics” (Bender Reference Bender, Bender and Smith2000:32) and urge archaeologists not to claim sole ownership over the past. They emphasize the role that archaeology plays in helping “students think productively about the present and future,” engaging “diverse audiences” (Bender Reference Bender, Bender and Smith2000:32–33).

As society changes and we as instructors come to new realizations of both the barriers to and the possibilities for equity and justice, we continue to revise our approach by asking, “Who is helped and who is harmed by archaeological knowledge production?” To teach archaeology is to produce the discipline, and we find that this comprehensive revision of our curriculum more closely adheres to the discipline we aspire to work both for and within. What makes us interested in archaeology is the endeavor to reconstruct the processes of the past in service of a better future—and to do so in a way that centers the needs and priorities of diverse stakeholders. Those values should be incorporated into teaching the discipline from the very first day students encounter it.

Acknowledgments

The study of student writing responses was undertaken with permission from the Institutional Review Board of Beloit College, and we thank them for their timely review. Quave's efforts in course revision were funded through a grant from the Andrew Mellon Foundation to Beloit College (“Decolonizing Pedagogies”) while she was faculty there, and she is grateful to Lisa Anderson-Levy for consultations on the course. Greiff and Agnew thank Dr. Sonya Maria Johnson for teaching us to prioritize inclusive nomenclature and be empathetic learners and educators. We thank Ellenor Anderbyrne for providing enrollment data, the Logan Museum staff (Nicolette Meister, Dan Bartlett, and Bill Green) for assistance with museum collections, and Jedidiah Rex for UDL consultation. With Fie and Agnew, the following students collaborated in spring 2017 to identify case studies: Christopher Allen, Alex Flores, Faith Macdonald, Sarah Record, and Heather Warner. Sarah Kennedy and Scotti Norman generously provided feedback in the draft stage. We thank the very helpful anonymous reviewers. Most of all, we thank our BIPOC peers, collaborators, and community stakeholders who have influenced our thinking on these issues; and we thank the students of ANTH 110 who patiently allowed us the space to experiment and gave their consent for us to share their thoughts about the impacts of the course changes.

Data Availability Statement

Sample course materials, including syllabi and assignments, are available in the Supplemental Materials. The student reflection papers are not available for sharing due to consent agreements that the papers remain password protected. Simplified college enrollment data discussed here are included in the Supplemental Materials. The authors chose to include the dichotomized race/ethnicity variable rather than full details of race and ethnicity in order to avoid making students identifiable. For that same reason, gender and other social identity variables are excluded.

Supplemental Materials

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/aap.2020.43.

Supplemental Text 1. Syllabus from the first semester in which the course was revised, with an additional column in the schedule that includes notes for lesson planning.

Supplemental Text 2. Excavation report/reflection assignment instructions.

Supplemental Text 3. Instructions for in-class activity on sensory experiences with artifacts, comparison of art/artifact dichotomies, and critique of the anthropological gaze.

Supplemental Text 4. Instructions for in-class activity on interpreting histories of enslaved peoples.

Supplemental Text 5. Assignment instructions and evaluation criteria for the Anti-Colonial Archaeology Textbook.

Supplemental Text 6. Pre-term and post-term assessment instructions. Responses were used to investigate the impacts of the course revisions.

Supplemental Table 1. Comparison of Tables of Contents of Major Introductory Archaeology Textbooks That Are Organized by Complexity.

Supplemental Table 2. Comparison of Tables of Contents of Major Introductory Archaeology Textbooks That Are Organized by Geographic Regions.

Supplemental Table 3. Historic Enrollment Data for Introductory Archaeology Survey Course.

Supplemental Table 4. Historic Enrollment Data for Intermediate-Level Archaeological Methods Course.