1 Introduction

According to the literature, pre-trial detention is used extensively in Latin America as a precursor to sentencing (CIDH, 2001; Gaudin, Reference Gaudin2011; Riego and Duce, Reference Riego and Duce2009; Ungar, Reference Ungar2003). Pre-trial detention is not always a judicial decision applied under certain exceptional circumstances (based on the severity of the crime, repetition of offences, danger for the victims, risk of obstruction of justice, etc.), but rather a systematic practice: pre-trial detention accounts for 40 per cent of the incarcerated population in the region (OAS, 2012). The use of pre-trial detention has many negative consequences, ranging from institutional (overcrowded prisons, violence in prisons, human rights violations – Coyle, Reference Coyle2003) to community (social disintegration – Clear, Reference Clear2008), household (family disintegration – Robertson, Reference Robertson2007) and economic spheres (financial losses – Buromensky et al., Reference Buromensky, Serduk and Tocheny2008), among others.

Reasons for pre-trial detention include:

• increasing crime rates have led to increased social and political calls for the punishment of ‘delinquents’, overriding the presumption of innocence that should prevail until the moment of sentencing (Calderón, Reference Calderón2011);

• criminal policies include higher rates of incarceration as a solution to problems of violence and delinquency (Ahumada et al., Reference Ahumada, Farren and Williamson2013; Carranza, Reference Carranza and Carranza2009; Riego, Reference Riego2012);

• institutional weaknesses of judicial systems allow suspects to easily evade justice when conditional release is permitted during the judicial process; at the same time, the system cedes to political pressure supporting the application of a ‘heavy hand’ on crime (CIDH, 2011; Pásara, Reference Pásara2013; Bernal and La Rota, Reference Bernal and La2013; Vintimilla and Villacís, Reference Vintimilla and Villacís2013).

Nevertheless, these explanations are not always empirically proven, and scarce quantitative evidence exists to support them. Evaluations of criminal justice systems in the region consider different aspects of the judicial process, but are based on the number of cases in which pre-trial incarceration is used, or the ‘outcomes‘ of the system (Blanco, Reference Blanco2010; Poblete, Reference Poblete2010; Vera Institute of Justice, 2002). There are no studies that look at the differences between cases (according to crime type) and legal-defence activity in Latin America. Pre-trial detention can also be seen as the outcome of activities and decisions made by defence attorneys, prosecutors and judges. In fact, some studies have focused on the issue of pre-trial detention from the perspective of the prosecutors and judges involved (Cavise, Reference Cavise2007; Hafetz, Reference Hafetz2002; Tiede, Reference Tiede2012). It is possible to argue that the activity of the defence is important in explaining prosecutors’ and judges’ reactions when faced with defence initiatives. To understand pre-trial detention, it is necessary to examine how the defence obtains conditional release (Colbert et al., Reference Colbert, Paternoster and Bushway2001; Kramer et al., Reference Kramer, Wolbransky and Heilbrun2007; Resnik, Reference Resnik2002).

In this respect, this paper examines the role of the defence in pre-trial incarceration, to explain the two ways in which (public and private) lawyers can get their clients released during the judicial process: (1) by informing clients of their right to request conditional release or (2) by requesting conditional release.

The inquiry will be answered with empirical evidence collected in Latin America: a survey of the incarcerated population carried out in multiple countries (Argentina, Brazil, El Salvador, Chile, Mexico and Peru), which allowed the collection of data related to inmates’ judicial processes.

1.1 Socio-economic context and carceral expansion

The international economic transformations and the disappearance of industrialisation to be replaced by import substitution that began in the 1950s had a significant impact on Latin American economies, provoking a decline in employment in the manufacturing industry. From the 1980s, these economies have experienced a significant reduction in their urban labour markets, converting a mass of unqualified young people into a chronically idle population (Fajnzylber, Reference Fajnzylber1983). At the same time, Latin American social policies did not adequately address this social and economic transformation, and thus many poor young people turned to crime. The 1990s saw a significant increase in criminal activity in the region (Beato, Reference Beato2012; Carranza, Reference Carranza2012; Vilalta, Reference Vilalta2015). This was due to a greater supply of people willing to participate, the growth of illegal markets and weak state institutions that could not control these phenomena (Arias, Reference Arias2017; Bergman, Reference Bergman2018; Dewey, Reference Dewey2015).

As crime increased in the region, so did punitive responses (Garland, Reference Garland2001; Sozzo, Reference Sozzo2016). The rise in incarcerations was largely due to a marked increase in fear of crime, profound social transformations and a decline in social solidarity (Bergman and Kessler, Reference Bergman and Kessler2008; Dammert, Reference Dammert2012; Dammert and Salazar, Reference Dammert and Salazar2009; Iturralde, Reference Iturralde2010; Sozzo, Reference Sozzo2016). The rise in crime also increased citizens’ demands for a ‘heavy hand’ on crime (Dammert and Salazar, Reference Dammert and Salazar2009; Vilalta, Reference Vilalta2010), resulting in many countries toughening conditions for conditional release – expanding the use of pre-trial detention.

With the increase in crime in the region, pre-trial detention and imprisonment became the preferred solutions of those politically answerable to the social demands for greater security. The incarcerated population duplicated during this period, incorporating a high percentage of inmates who had committed minor crimes (drug trafficking and minor theft). Approximately 60 per cent of inmates served sentences for these types of crimes.

1.2 Research context

Pre-trial detention aims to detain a person accused of committing a crime during the process of deciding their guilt or innocence (Zaffaroni, Reference Zaffaroni1988, p. 717) in order to ensure an objective trial, by preventing the detainee from interfering in investigations or from simply evading the enforcement of justice. It is a controversial institution, as the judicial system supposedly assumes a person's innocence until he or she is proven guilty. Despite this presumption of innocence, the criminal procedural code allows a judge to order the pre-trial incarceration of a defendant. This situation has been amply discussed and is at the centre of the debate over the guarantee of a right to a fair trial – one of the most interesting legal debates in recent years (Ferrajoli, Reference Ferrajoli1990). It also forms part of the debate on the process of criminal expansion in post-neoliberal Latin America (Ávila, Reference Ávila2013; Dávalos, Reference Dávalos2014; Sozzo, Reference Sozzo2015). The aggressive application of pre-trial detention plays a fundamental role in the increase in mass incarceration in response to the issue of crime, to the detriment of a rights-based penal regulation. Some authors have referred to this as the ‘constitutionalisation of criminal law’ (Ávila, Reference Ávila2009; Reference Ávila2013; Dubber, Reference Dubber2004). Indeed, pre-trial detention is at the centre of political discourses that promote ‘tough-on-crime policies’, ‘heavy handedness’ and ‘zero tolerance’ in the social construction of a new punitiveness in the region (Cerruti, Reference Cerruti2013; Pontón-Cevallos, Reference Pontón-Cevallos2016). Pre-trial detention is associated with the ‘revolving door’ of the law: when it is not applied, the media tend to label the law a ‘soft power’ by which criminals who are detained by the police are freed by judges (Tsukame Sáez, Reference Tsukame2016).

In Latin America, constitutions specify the terms under which pre-trial detention may be applied. This practice is carried out when:

1 the crime committed is serious or is a high-social-impact crime (kidnapping, homicide, human trafficking, rape, robbery, serious injury, involving the use of firearms);

2 there have been repeated offences of a serious crime;

3 other measures to guarantee that the accused will not escape are insufficient;

4 the investigation might be compromised if the accused is set free;

5 the victim(s), witness(es) or the community is at risk and should be protected;

6 an exceptional case.

There are three general principles of pre-trial incarceration: necessity – it is indispensable; proportionality – it avoids unnecessary suffering; and reasonableness – it is within temporal limits (United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Administration of Juvenile Justice, 1985, available at https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/ProfessionalInterest/beijingrules.pdf (accessed 30 November 2020)).

The use of pre-trial incarceration has been studied in depth since the 1960s. Focal points include the effects of pre-trial detention on sentence and imprisonment decisions (Williams, Reference Williams2003); its constitutionality and relation to conditional release (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell1969; Meyer, Reference Meyer1972); the delicate problem of juvenile pre-trial incarceration (Guggenheim, Reference Guggenheim1977; Frazier and Bishop, Reference Frazier and Bishop1985; Holman and Ziedenberg, Reference Holman and Ziedenberg2006; Worrell, Reference Worrell1985); and the broad array of indirect effects of pre-trial incarceration on the cumulative disadvantages of certain social sectors based on race, sex, poverty, etc. (Spohn, Reference Spohn2008; Wheeler and Wheeler, Reference Wheeler and Wheeler1980).

Pre-trial incarceration has a central role in due process and provides a framework for the analysis of bail decision-making (Devers, Reference Devers2011), as well as the judicial decision-making process in general (Clark and Henry, Reference Clark and Henry1996; Gottfredson and Gottfredson, Reference Gottfredson and Gottfredson1990), interim decisions of the defence (Clark and Kurtz, Reference Clark and Kurtz1983), factors influencing the release of an accused (Phillips, Reference Phillips2004) and judges’ control of discretion in prescribing pre-trial detention (Walter, Reference Walter1993). The role of judges has been particularly widely studied, specifically how ‘grounds for pre-trial detention are easily accepted by the judges‘ even though ‘the existence of those grounds in the specific case is not proven sufficiently‘ (Crijns et al., Reference Crijns, Leeuw and Wermink2016, p. 7). Judges’ reluctance to grant bail, either because they are unfamiliar with this possibility or because they fear that the accused will escape, appears to be universal (Stevens, Reference Stevens2013). This situation is even worse in countries where judges have investigative faculties, as they tend to prefer advancing in the collection of evidence with the security of having the accused detained (Field, Reference Field1994) and without risk of flight or obstruction. That said, beyond the role of judges, the discussion has also dealt with judges’ bias when dictating pre-trial detention, such as regarding race (Rengifo et al., Reference Rengifo2019), judges’ fixed effects (Frandsen et al., Reference Frandsen, Lefgren and Leslie2019) or their purely symbolic role (Arango, Reference Arango2010) in the pre-trial detention decision.

In the wide range of literature, only a few references quantitatively link pre-trial incarceration to the defence, such as the study of Colbert, Paternoster and Bushway (Reference Colbert, Paternoster and Bushway2001), which examines the absence of legal defence at bail hearings in the US, or the work of McConville, Hodgson, Bridges and Pavlovic (Reference McConville1994), which analyses the organisation and practice of criminal defence lawyers in Britain. The study that most closely makes this connection analyses the (public/private) legal defence of poor criminals in Houston courts by following 586 cases over the course of a year, up until sentencing (Wheeler and Wheeler, Reference Wheeler and Wheeler1980). The study suggests that there is no difference between the number of acquittals obtained by private and public lawyers for their clients (controlling for the criminal charge and previous convictions). Despite this, private attorneys obtained non-prison dispositions more often than court-appointed attorneys. The study also noted that pre-trial detention was the most statistically significant predictor of case-disposition rates. In addition, some defendants jailed before trial were seemingly held as a result of the ineffective counsel of their defence attorneys.

In Latin America, reviews have focused on human rights (Hafetz, Reference Hafetz2002), criminal procedure (Bischoff, Reference Bischoff2003; Langer, Reference Langer2007), criminal policies (Rodríguez, Reference Rodríguez2010), confinement of minors (Axat, Reference Axat2008), penitentiary reform (Matthews, Reference Matthews2011) and pre-trial incarceration as an early sentence (Fuentes Maureira, Reference Fuentes2010). The subject has mostly been studied by nonprofit organisations, both local (such as the American Bar AssociationFootnote 1 and the Justice Studies Center of the AmericasFootnote 2) and international (The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human RightsFootnote 3 and Open Society FoundationFootnote 4), with the aim of intervening and limiting the widespread use of pre-trial detention (Ahumada et al., Reference Ahumada, Farren and Williamson2013; Zepeda, Reference Zepeda2010). Meanwhile, the defence has been studied in depth by legal scholars through criminal justice reform (Duce et al., Reference Duce, Fuentes and Riego2009), judicial independence (Pásara, Reference Pásara2013) and presumption of innocence (Valenzuela, Reference Valenzuela2011). Empirical (sociological) analysis is rare (Kostenwein, Reference Kostenwein2015) and much less so using quantitative information.

2 Data and methods

The data used in this study are the result of the Survey of Incarcerated Populations in Latin America conducted during 2014 and 2015 in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, El Salvador, Mexico and Peru. The sample acquired from the six locations comprises a total of 5,700 surveyed inmates (N: 5,561 weighted by gender). The sample design followed a random-selection process of units of observation and information in all cases. This was a complex, multistage sample process, stratified by conglomerates, with a systematic selection of observations and incorporating a gender quota. Two sampling frames were used: a selection of prison centres based on the distance between the centres, quantity and a selection of volunteer inmates in each centre with a systematic procedure, using a random starting point. Each sampling frame was used at different stages of the selection process (selection of the prison and of the survey respondents).

The effects of the survey design and response rates of the incarcerated population are relatively varied across countries and regions. The maximum variability possible was assigned; a confidence level of 95 per cent and a maximum theoretical precision level of ±5 per cent were estimated. The sample was stratified by inmate gender. It was necessary to overrepresent women numerically in the surveys, as they are a small proportion of the total incarcerated population.

The questionnaire consisted of around 310 closed-ended questions on life in prison, sociodemographic characteristics and the judicial process, among others. The interviews lasted roughly forty-five minutes each and took place in a location specifically designated as guard-free. Lastly, it is important to note that the descriptive presentation of the data does not consider the response ‘do not know/no response’ (dnk/nr) as an option, due to its low frequency (less than 2 per cent of the total).

2.1 Limitations and advantages of the survey

The analysis is based on information provided by people who were sentenced for committing specific crimes and, therefore, cannot be extrapolated to the broader population of people who were freed during the judicial process (only 3.8 per cent obtained conditional release during the process as a result of their legal defence's efforts).

A good statistical model cannot be completed on the relationship between legal defence and pre-trial detention. All the respondents committed, or at least were sentenced for committing, a crime. Thus, once again, only one side of the story is reflected: the data lack testimonies from people who were found innocent. It would be wrong to make assumptions from a sample of prison surveys from a Bayesian perspective.

The differences between the criminal procedural codes of each country can also account for differences in answers (although there are differences in the detail between the various criminal codes, in all cases, violence, the use of firearms and the damage caused are determinants for denying conditional release). Furthermore, only one wave of surveys was done in each country, providing a mere snapshot of the situation; this limits the possibility of generating a historical conceptualisation of the issue at hand.

Given this, the quantitative approach of the survey is particularly useful for addressing the relationship between the quality of the defence and pre-trial detention, as it allows the development of models and statistical testing to verify hypotheses. Furthermore, having the same data on a regional level (by using the same instrument) facilitates comparisons between countries and the highlighting of regional trends. As opposed to a qualitative approach, the survey is able to show the systematic causal links between defence quality, or lack thereof, and a judicial provision on pre-trial detention. Although the qualitative insight that explains the shortcoming of the defence (from the voice of the actors involved) may be missing, the survey permits the correlation of variables that can, subsequently, be explored qualitatively.

3 Tests and models

Two sets of tests were performed – Set 1: the five countries/regions as a whole with all the crimes; and Set 2: each country/region separately with only one crime (theft). Set 1 has more data but national/regional details are lost and some homogeneity in criminal codes must be assumed, whereas, in Set 2, regional specificity is gained but many data are lost and only one crime can be analysed: theft (without control variables).

3.1 Set 1: five countries (all crimes)

T-tests were done regarding the work of lawyers of two independent groups: (1) the accused with private defence attorneys vs. (2) the accused who had public defence attorneys. Three activities were tested for thirteen different types of crime: (1) percentage of defendants informed of conditional release, (2) percentage of defendants whose attorney requested conditional release and (3) percentage of defendants who obtained conditional release (efficacy).

3.2 Set 2: each country (theft)

Z-scores were done regarding the work of lawyers between two independent groups: (1) the accused who had private defence attorneys vs. (2) the accused who had public defence attorneys. Three activities were tested for five different countries and one type of crime (theft): (1) percentage of defendants informed about conditional release, (2) percentage of defendants whose attorney requested conditional release and (3) percentage of defendants who obtained conditional release (efficacy).

Theft represents 44 per cent of the total base – weighted by gender (in El Salvador the percentage is very small) and 63.2 per cent of respondents had a public defender (first attorney) (see Appendix).

In addition, two ordinary least-squares (OLS) models were used on the dichotomous variables ‘Did someone inform you that you could be given conditional release until the end of the trial?’ and ‘Were you granted conditional release?’. The independent variable of the selection of a lawyer (public or private) was included in the two models; additionally, different control variables were included in each model: Model 1 includes only the dependent variable related to information of rights (0 = were not informed; 1 = were informed) controlling for attorney (public or private) and country; Model 2 includes the dependent variable related to the effectiveness in obtaining probation (0 = was achieved; 1 = was not achieved) controlling for attorney (public or private) and country.

4 Results

4.1 Set 1: five countries (all crimes)

4.1.1 Informing the client

A first important finding relates to one of the basic rights of any individual when detained by authorities: knowing whether or not they have the right to access conditional release during the judicial process. Of the total number of people whose first attorney was private (2,316), 26.7 per cent were informed of their right to conditional release. This percentage is lower for those who had a public attorney (3,161): only 21.1 per cent were informed of the existence and accessibility of conditional release.

As can be seen, little information was shared with the detainee/accused (client), with the lowest levels in Mexico (11.1 per cent, meaning that only one in every ten detainees was informed of this right) and the highest in Peru, where private attorneys informed 39.4 per cent of their clients.

This situation makes sense, given that these are violent crimes against people and therefore detainees would not have access to the benefit of conditional release according to the criminal procedure codes of the countries studied. However, in the case of non-violent crimes that could allow conditional release (unless there are other aggravating circumstances), the situation is not much better. Though there are significant differences between crimes, as well as levels of knowledge, depending on whether the lawyer is public or private, these differences apparently do not have a judicial logic.

Evidence shows that, even in cases of individuals who are potentially eligible for conditional release based on the crime they committed, attorneys do not inform their clients of this possibility. Various explanations exist for this, although the most probable is that, as the population is generally young (35 per cent of prisoners are aged between eighteen and twenty-nine) with low schooling levels (69 per cent of prisoners only have basic education), lawyers are used to taking decisions for their clients without consulting them. It is a form of ‘judicial paternalism’ that is common in the region. This is reflected in the low levels of understanding of the judicial process reported by prisoners: on average, 37 per cent claim that they did not understand the process.

This lack of information is confirmed by the low number of requests for conditional release (see Table 1). Of the total number of inmates whose first lawyer was private (2,283), 35.7 per cent requested conditional release. This percentage is greater than that of those who had a public attorney (3,091), where conditional release was only requested in 21.6 per cent of cases (the difference is statistically significant. n: 1,471; z: 11.449; p-value: 0.0001). Regression models confirm that having a private attorney significantly increases the probability of requests for conditional release by ~14 per cent.

Table 1. Comparison of the activities of public vs. private attorneys

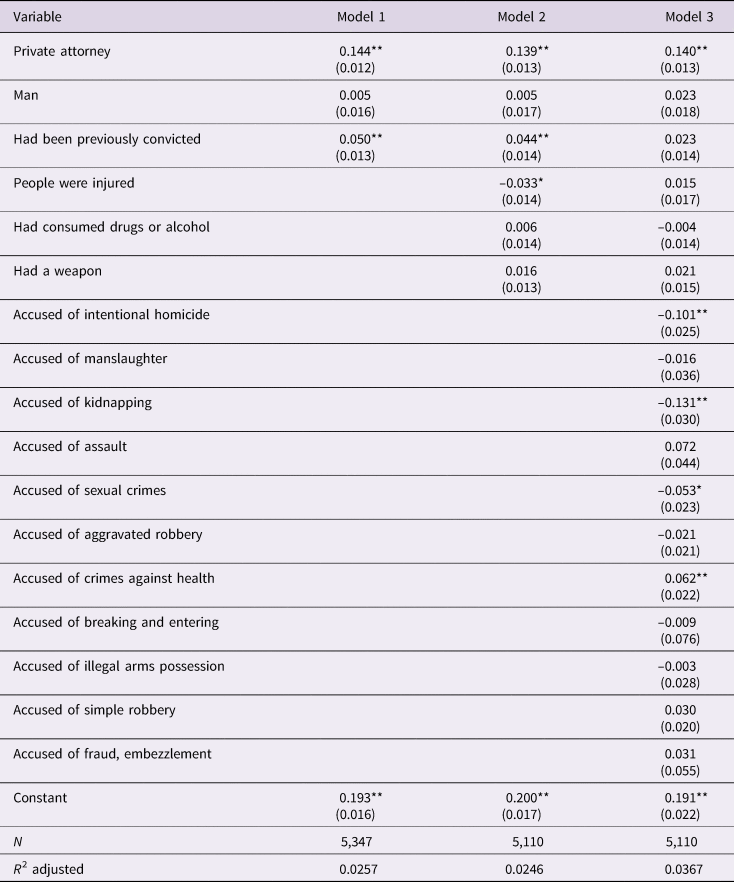

Questions: ‘When you were detained for the crime that you were accused of committing, did someone inform you that you could be given conditional release until the end of the trial?’ (n: 3,161 public attorney, 2,316 private attorney); ‘Did you or your lawyer request conditional release?’ (n: 3,091 public attorney, 2,283 private attorney); ‘Were you granted conditional release?’ (n: 662 public attorney, 810 private attorney). *Significant at 90%; **significant at 95%; ***significant at 99%. In addition, three OLS models were used on the dichotomous variable ‘Did you or your lawyer request conditional release?’. The independent variable of the selection of a lawyer (public or private) was included in the three models. Additionally, different control variables were included in each model. Model 1: includes only variables ‘external‘ to the crime committed. No characteristic of the crime is controlled for; only the characteristics of the person (gender and repeated offences) and the attorney (public or private). Model 2: includes the variables in Model 1 as well as some characteristics of the crime: whether people were injured or not, whether drugs/alcohol had been consumed and whether the defendant had a weapon (these are the crime circumstances most often used by judges to evaluate a request for conditional release). Model 3: includes the variables in Model 2 as well as a stratification by crime. This method covers almost the whole spectrum of conditions and possibilities for determining conditional release.

Table 2. Regression models

Question: ‘Did you or your lawyer request conditional release?‘ (n: 1,471). *Significant at 95%; **significant at 99%. All the coefficients of the models are interpreted as percentages.

Table 3. Z-score

Questions: ‘When you were detained for the crime that you were accused of committing, did someone inform you that you could be given conditional release until the end of the trial?’; ‘Did you or your lawyer request conditional release?’; Did you or your lawyer request to be released conditionally in exchange for a bond?; ‘Were you granted conditional release?’

Table 4. Regression Model 1

Question: ‘When you were detained for the crime that you were accused of committing, did someone inform you that you could be given conditional release until the end of the trial?’ (n: 2,294).

Table 5. Regression Model 2

Question: ‘Were you granted conditional release?’ (n: 663).

Table 6. Information shared with the detainee/accused (%)

Question: ‘When you were detained for the crime that you were accused of committing, did someone inform you that you could be given conditional release until the end of the trial?’ (n: 3,616 public attorney, 2,316 private attorney).

4.1.2 Requesting conditional release

The result of requesting conditional release has consequences for the judicial process: of the total number of people whose first lawyer was private, 13.7 per cent obtained conditional release. This percentage is lower than that of those who had a public attorney: 15.5 per cent. Despite the fact that private lawyers are more likely to inform their clients and request conditional release than their public colleagues, the resulting success rate is lower. Private attorneys appear to be more active but less successful than public ones.

Attorneys, both private and public, have little success when requesting conditional release for their clients: only 15.5 per cent of public attorneys and 13.7 per cent of private attorneys get this granted. The –1.83 per cent difference between the two is not statistically significant (n: 1,471; t: 1.1113; p-value: 0.2666). However, when separating the efficacy of attorneys based on crime type, differences in the efforts of private and public defenders can be observed. Only in the case of intentional homicide are private attorneys more successful, statistically, than public attorneys: 17.7 per cent obtained conditional release for their clients vs. 7.4 per cent for public attorneys. For all other crimes, public attorneys were more successful than private attorneys, with statistically significant differences found for sexual crimes (1.5 per cent), assaults (8.8 per cent) and illegal arms possession (10.9 per cent).

When considering the various aspects that could influence a judge's decision to grant conditional release, few observable differences are statistically significant between public and private defenders. Only in two cases is the efficacy of public attorneys greater than that of private attorneys: when the client is a repeat offender (14.67 per cent for the former and only 9.95 per cent for the latter) and when no one was injured during the crime (16.69 per cent for the former and 12.36 per cent for the latter). Percentages differences are not statistically significant in other cases.

4.2 Set 2: each country (theft)

4.2.1 Informing the client

To a certain extent, the data derived from the z-score tests of Set 2 corroborate most of the findings of Set 1 at a country level and for theft only: private lawyers inform their clients better than public ones in Argentina, Chile and Peru. However, in Mexico, public defenders seem to inform their clients more often.

The results of the OLS model reinforce these data, indicating that private lawyers informed detainees of the possibilities of conditional release more often than public lawyers – controlling for country.

4.2.2 Requesting conditional release

According to the z-score, in all countries, private lawyers asked for more probation. However, evidence indicates that both public and private defenders are very ineffectual in achieving probation for their clients (only 95 of 597 respondents received probation): 16 per cent of clients represented by a public lawyer and 12 per cent of those represented by a private lawyer. However, differences exist between types of defenders: public defenders request less probation, but their percentage of effectiveness is similar to that of private defenders. In Argentina, Mexico and Peru, the proportions are the same, which means that no significant differences exist between public and private lawyers. It could mean that public defenders are more strategic than private lawyers who request (much) more probation but probably with less evidence (so are less strategic). In Chile, public defenders achieved more probation whereas, in El Salvador, private defenders were more successful.

Again, the OLS model confirms the above finding, as it indicates that private lawyers are no more effective in obtaining probation than public lawyers (although they ask for it more often). This is consistent across all countries.

5 Discussion

The findings reveal that the problem of pre-trial detention is not one that should be addressed solely by the courts. It seems clear that defence attorneys (both public and private) play an important role in pre-trial incarceration. At the same time, there are differences between lawyer type when informing and requesting conditional release for their clients.

The lack of a more liberal use of conditional release does not appear to depend on judicial aversion to the risk of escape nor to the following classic motivations: the presumption of the perpetration of a crime, the need for investigation, the possibility of collusion, pressuring of witnesses and the preservation of public order (Pastor, Reference Pastor1993; Dressler, Reference Dressler1996; Pinto, Reference Pinto2007). These results seem to point in another direction regarding pre-trial detention:

• defence attorneys do: request conditional release unequally (and also obtain it unequally) and use extenuating circumstances of each case strategically (they exhaust all possible resources related to the particular possibilities of attaining conditional release);

• defence attorneys do not: universally inform their clients of their right, correctly inform their clients (according to the crime) and universally request conditional release.

5.1 Defence attorneys do

According to regression Model 2 (Set 1), in cases of repeat offences, the number of successful requests for conditional release increases. This is probably because repeat offenders know the system better and know that they can ask for the benefit (which does not necessarily imply better defence activity). When repeat offences are not significant (in Model 3, Set 1), lawyers decide whether or not to request conditional release depending on the crime the client is accused of: for example, there is a lower probability that a lawyer will request conditional release for a person accused of intentional homicide than for one accused of manslaughter. Public defenders request conditional release less often but are simultaneously more successful (unlike in the study of Wheeler and Wheeler in Houston, Reference Wheeler and Wheeler1980). This means that they request conditional release strategically and only in situations with a high probability of obtaining it (due to the low severity of the crime committed or the lack of injured people, etc.), while withholding the request in situations in which it is unlikely to be granted (intentional homicide, kidnapping, sexual crimes). Meanwhile, private attorneys are more proactive in requesting conditional release (higher frequency of requests) but less strategic, as they do not discriminate between cases. Thus, although they present more requests, they obtain fewer releases through conditional release. Hence, in the results, no significant difference exists despite the differences in percentages: 13.7 per cent success for private attorneys, contrasting with 15.5 per cent success for public defenders. Set 2 mirrors these results: the general total of the proportions between public and private lawyers asking for probation has a significance of 0.999; and Model 2 consistently shows that private lawyers are no more effective than public ones in securing probation, across all countries. In summary, public defenders request conditional release less frequently, but more effectively.

Although the surveys do not offer information regarding lawyers’ motivations, it is suggested that: (1) public attorneys with high case-loads do not waste time on those with low probabilities of success (in fact, they generally do not have much time; e.g. the Mexico City public defence system currently employs 231 lawyersFootnote 5 and an average of 37,500 individuals per year turn to the public defender; this means that each public defender receives an average of 162.33 cases per year, i.e. one new case approximately every day and a half – 1.47 – not including rest days). They are thus more risk-averse, as they do not gain anything by attempting something that is unlikely to be successful, whereas (2) private attorneys have a financial relationship with their client based on their level of activity.

These two hypotheses potentially explain the unequal sharing of information of lawyers with their clients, since it does not follow a judicial process (informing in accordance with the criminal procedure code):

• in the case of public defenders, this unequal sharing of information may be a strategic behaviour (attorneys know which crimes have a higher probability of receiving conditional release independently of what the criminal procedure code states or they are not interested in cases in which a judge must call for pre-trial detention based on the procedure due to the type and severity of the crime) and/or some kind of ‘judicial paternalism’;

• in the case of private attorneys, they may inform their clients for other reasons.

The analysis of the results for regression Model 3 (Set 1) seems to indicate that both types of defenders (public and private) use extenuating circumstances in a similar way to request conditional release. In contrast to the selection of cases in which public attorneys appear to be more strategic compared to private ones in the previous models (Models 1 and 2, Set 1), once cases are chosen, lawyers use extenuating circumstances to support the request for conditional release. Despite the fact that, in some processes (repeat offences and lack of damage), public defenders show better results than private ones, in general terms, there are no substantive differences to suggest that one type of defence attorney is more strategic (or successful) than another. Both take advantage of the same possibilities offered by extenuating circumstances in each case.

Finally, it must be remembered that the aforementioned remarks focus on a small percentage of the defence's activity, as, in the vast majority of cases, defence attorneys do not inform their clients of conditional release and, when they do inform them, they do not do so correctly (according to the crime) and do not universally request this conditional release (like the analysis of bail hearings by Colbert et al., Reference Colbert, Paternoster and Bushway2001). The most frequent situation is that conditional release does not appear to play any role in the defence strategy of the accused. This point, in particular, deserves further research, in order to understand the disinterest in conditional release.

Nevertheless, the data seem to show that the work of attorneys is fundamental to understanding the other side of pre-trial detention, which is unrelated to the increase in sentencing (Calderón, Reference Calderón2011), the weakness of the judicial system (Pásara, Reference Pásara2013; Bernal and La Rota, Reference Bernal and La2013) and prison policy (Carranza, Reference Carranza and Carranza2009; Riego, Reference Riego2012); rather, it is directly related to the exercise of criminal law. This issue tends to be overlooked by legal policies, probably due to a lack of data on the behaviour of the defence and the prejudice that assumes that pre-trial detention is based on a series of conditions and evidence that do not deserve much interpretation. This study shows that pre-trial detention also depends on the decisive role played by the defence. Thus, it is impossible to change the workings of the judicial system without modifying these types of behaviours, which affect the outcome of processes. Although judges seem reluctant to grant bail, this should not deter the defence from developing strategies to obtain their clients’ freedom during the process. The defence must therefore be included in any judicial policy aimed at dealing with this issue.

Conflicts of Interest

None

Acknowledgements

None

Appendix: Challenges of conducting research in prisons

Prisons are self-contained environments in which all activities are systematically controlled and monitored. Due to this lack of privacy, contact and liberty, and other factors such as isolation, inmates are often considered a vulnerable population for the purpose of research studies (Bulman et al., Reference Bulman, García and Hernon2012). The time spent in prison and the conditions within (minimum, medium and maximum security) influence the type of responses and perceptions the interviewees share. These elements inhibit the development of a rigorous evaluation that allows the isolation of the effects of these imprisonment factors, which complicates comparative studies of incarcerated people (as prison causes different effects). As a result, the inmate survey used in this study has some limitations, as follows.

Although 83.7 per cent of the sample were individuals detained during the period between 2006 and 2012, it is important to note that a long time in prison could have affected the accuracy of the recollections of the detainees who have spent many years in prison (the interviewee who had spent the longest time in jail was incarcerated in 1978). Even though it is not possible to clearly distinguish whether this affected the accuracy of their recollection, the results presented are inmates’ reports of their legal defence, which means that some underreporting that is difficult to quantify is likely; it is not possible to control the variables for other important contextual factors (such as requests for conditional release presented to the judge by the defence) that could bring more solidity and breadth to the data.

Another problem is the interviewees’ lack of understanding of the judicial process: 37.7 per cent stated that they understood little and 30.7 per cent stated that they had not understood any of it (Q. 259: ‘Now, thinking back over your trial and hearings, how much did you understand of what was happening at the hearings and trial?‘). The potential complexity of criminal justice cases and defence arrangements was accounted for and controlled for by the type of sentence sought based on the accusation and final sentence received.

Table A1. Percentages of theft

Table A2. Percentage of defenders – theft