1 INTRODUCTION

The morphological behavior of anglicisms in French is poorly understood, as evidenced by the paucity of research on the topic (e.g., Humbley's bibliography of French anglicisms, Reference Humbley and Görlach2002). The reason for this deficiency may be the assumption that these English words are completely integrated into French, since foreign words are typically classified as borrowed forms at the point when their adoption of the morphological features and/or phonological shape of the recipient language can be attested. Myers-Scotton (Reference Myers-Scotton2006: 224) even refers to morphological integration as close to a ‘universal’ marker, arguing that ‘[. . .] borrowed words are almost always [italics in original] adapted to the recipient language in morphology (adapted in form).’ The dictionary-attested English adjectives bobo and cockney, for example, receive the French affix −s in the plural (e.g., des robes bobos, des accents cockneys), which is a transparent indicator that the donor adjectives are pluralized like any other adjective by the morphology of the recipient language. Though native overt inflection is the most common pattern, it is not yet universal. There is a set of borrowed adjectives that remain morphologically unmarked (e.g., des musiciens groggy, des yaourts light) and a smaller set that exhibits variation (e.g. des musiciens punk or des musiciens punks). When English adjectives are used in the plural, then, they follow one of these three patterns: they (1) receive inflection, (2) reject inflection, or (3) accept both inflected and uninflected forms.

These phenomena are observed based on a closed dictionary corpus composed of the complete list of the 395 English-origin adjectives recorded in the Petit Robert (2010). Because of unavoidable biases associated with dictionary data, a Libération newspaper corpus was subsequently used to compare and validate the inflectional status provided by the dictionary and thus ensure a treatment compatible with (press) usage. This article interprets these morphological patterns of variation, particularly the exceptional forms that make it necessary for Myers-Scotton to qualify her generalization with ‘almost always,’ and identifies constraints that may inhibit and facilitate inflection. A second salient, and quite puzzling, feature of the pluralization of adjectival English borrowings in French is that the nominal counterpart of the uninflected and variable forms, if it exists, always receives native inflection, as illustrated with the pairs des jeans baggy (adj.) vs. des baggys (n.) and des tournois open (adj.) vs. des opens (n.). Why are the constraints that block inflection on adjectives not also imposed on nouns?

The analysis proceeds in five major sections. It (1) proposes a general hypothesis for the morphological integration of adjectival anglicisms; (2) presents the study's methodological parameters and motivations for a closed corpus of dictionary-attested adjectives; (3) proposes a classification of borrowing types tailored to the dictionary list of English-origin adjectives that broadly correlates with degree of inflectional integration; (4) identifies inflection-facilitating conditions; (5) specifically explores inflection-inhibiting constraints; and (6) offers an analysis for the contrastive behavior of adjectival vs. nominal counterparts.

2 A MORPHOLOGICAL HYPOTHESIS FOR ENGLISH ADJECTIVAL BORROWINGS

Rey-Debove (Reference Rey-Debove1973: 111) claims that native speakers apply rules to borrowed forms that are conditioned by their borrowed (vs. native) status: ‘Il existe des lois de l'emprunt (et de néologie) qui sont inscrites dans la compétence linguistique d'un décodeur monolingue.’ Curiously, however, these rules particular to borrowed words have been neither investigated nor formulated, and so the motivation for inflecting certain English adjectives and not others remains unexplained to date. The field of study has concentrated on English borrowed forms because they are the most frequent and thus provide a substantial and homogeneous corpus, with the acknowledgment that borrowings may behave differently from one donor language to another. Chesley (Reference Chesley2010) proposes sense pattern (monosemous/polysemous) and cultural context (restricted/unrestricted) as qualitative indices of the integration of borrowings, and argues that anglicisms behave differently from non-English borrowings in being polysemous and occurring more often in culturally unrestricted contexts.

This analysis of the pluralization of English-origin adjectives is based on the testing and validation of the following hypothesis: the inflectional behavior of adjectival anglicisms is governed by borrowing rules that differ from those that characterize native French words. It is well-known that the integration of borrowings is commonly a gradient phenomenon, thus involving various phases through various linguistic processes and forms (e.g., Rey-Debove's analysis of the semiotic and stabilization patterns of the English noun grouse in French, Reference Rey-Debove1973; Rey-Debove, Reference Rey-Debove, Rey-Debove and Gagnon1988: VII-VIII; Winford, 2010: 173–175). Age of borrowing and degree of integration do not systematically correlate, however. For example, while the date of attestation of the adjective smart in the French lexicon is 1898, the form has never adopted native inflection; in contrast, the recently borrowed addict (1985) regularly takes the affix −s in the plural. This research focuses on the exploration of constraints that would explain non-native inflectional behavior beyond the incontestable factor of length of time in the recipient lexicon.

Bare English adjectives in French may not be morphologically deviant, especially when correlated to the phonological behavior of certain borrowings and the behavior of certain native adjectives. First, as the phonology of anglicisms is not always adapted to that of native French words, it may be the case that their morphology is not systematically adapted either. In phonology, it is recognized that English words in French may have their own rules (Picard, Reference Picard1983). In Québec French, phonological rules that apply categorically may fail to apply to words of English origin. For example, the absence of affrication before /i/ in words like t-shirt and the absence of laxing of high vowels in words like jeans deviate from Québec French patterns. In standard French, the productive English-origin suffix –ing has been richly studied as an example of the integration of a non-native phoneme: “The velar nasal [/ŋ/] in French has clearly received phonemic status despite its restricted distribution,” concludes Lewis (Reference Lewis2007) in her comprehensive review of the complex phonology of –ing in French. If anglicisms have their own phonology, it is conceivable that they have their own morphology as well.

The second, correlated, observation is that variable and invariable native adjectives coexist in French. While number agreement is a salient feature of the morphology of French adjectives, there are sets of adjectives that reject plural affixation. Grevisse's Le bon usage (Reference Grevisse and Goosse2008: 715–730), probably the most authoritative French grammar, provides a rather complex classification of invariable adjectives. Among these adjectives are: nouns used as color adjectivesFootnote 2 (e.g., noisette, grenat vs. rouge, bleu); adverbs used adjectivally (e.g., des places, debout des femmes bien); colloquial adjectival creations, especially those derived via a reduplication process (e.g., cracra, raplapla); foreign adjectives (e.g., German kit(s)ch, Hebrew casher or kascher). These uninflected adjectives show that deviation from standard patterns of French morphology is permissible. And the last category, specifically, shows foreign borrowings to be a subset of uninflected adjectives.

3 METHODOLOGY

The morphological behavior of English-origin adjectives is observed in the written language only due to fundamental differences between the realization of written and oral adjectival inflection in French. The choice of written data was imposed by the fact that the plural marker −s on adjectives is realized orthographically. In contrast, the plural marker on adjectives is not realized in the spoken language except for irregular forms (e.g., sg. loyal vs. pl. loyaux) and for phonological contexts such as liaison (e.g., prenominal adjective: gros_érables /grozerabl/). Consequently, only written adjectival morphology can reveal the inflectional integration of English adjectives. The motivations for collecting English adjectives from a dictionary corpus and morphologically controlling this corpus with current newspaper data follow.

3.1 Corpus of dictionary-attested adjectives

In order to analyze a homogeneous corpus of borrowings and limit the scope of data collection, the investigation is restricted to a closed corpus of English-origin adjectives recorded in the 2010 edition of the general language dictionary the Petit Robert (PR). It can be assumed that these are well-established forms in the French language: “[t]hough institutionalization does not necessarily go hand in hand with adaptation, it often does” (Fischer and Pułaczewska, Reference Fischer, Pułaczewska, Fischer and Pułaczewska2008: 9). Similarly, acceptance in the dictionary testifies, among other thorny factors of evaluation, that words have sufficient usage and longevity and, for borrowed forms in particular, a sufficient degree of assimilation to be considered members of the recipient lexicon (Lieber, Reference Lieber2010: 27). The Petit Robert corpus then provides a useful corpus for investigationFootnote 3 despite lexicographic limitations briefly addressed below.

The etymology search function supplied by the Petit Robert's electronic version facilitated the identification and collection of all of the 395 English-origin adjectives from the dictionary word list. I then examined the plural form(s) of each adjective as given in the entry and formed three groups—inflected, uninflected, or variable—in which I placed each. The Petit Robert's editor, Alain Rey, insists that the dictionary reflects real usage, regardless of the norm: ‘Le «bon usage» convenait peut-être à l'Ancien Régime, mais demande sérieuse révision, et ce sont plusieurs usages, plus ou moins licites et que personne ne peut juger «bons» ou «mauvais», qui forment la réalité d'une langue’ (Postface of Petit Robert). Although the Petit Robert is one of the least conservative French language dictionaries, a dictionary by its very nature imposes a norm, a framework for the coherent organization of data, thus unavoidably masking diachronic processes and changes such as the integration of borrowings.

The choice of a dictionary approach can then be problematic because of discrepancies between contemporary usage and what is recorded in the dictionary. To account for this, I then compared the three groups of English adjectives, based on their inflectional status as stated in the dictionary, with the plural occurrences of each in the language of the press, a well-known port of entry for anglicisms. This comparative task permitted testing of the Petit Robert's inflectional classification against current usage. Any discrepancy resulted in readjustment of the groups. For example, the adjective gay is considered uninflected in the dictionary, but in press usage, the form shows clear fluctuation and was consequently moved to the group of variable adjectives in the final classification.

3.2 Libération data

The online daily newspaper Libération provided the main source of press data and was selected for being one of France's major national papers and at the same time the most informal of the national papers, which ensures a language that does not condemn anglicisms. (Though this correspondence by no means implies that more conservative press refrains from using them.) More specifically, culture occupies a core section in Libération (Guisnel, Reference Guisnel2003), and cinema and music represent concentrated sources of anglicisms (Walter, Reference Walter1997; Pułaczewska, Reference Pułaczewska, Fischer and Pułaczewska2008).

The newspaper's database allows access to archives covering the years 1994–2011. Though the plural is the marked form of adjectives, i.e., the least frequent and least regular form, and as such is less frequent than the singular, the online database was large enough to generate a significant sample of plural forms. All of the examples that came up for each adjective search were manually examined, for two reasons. First, certain adjectives are used not only as adjectives but also as proper nouns or as part of compound constructions, or they have a nominal counterpart, such as the case of the adjective black whose query yielded occurrences of the rock band name Black Eyed Peas, the nominal compound black-out, and the noun des blacks, among other senses and uses. Manual control permitted identification and exclusive extraction of exact adjectival matches. Second, the context in which the forms occur in the articles needed to be determined in order to separate singular (1) from plural (2) occurrences, as this Libération sample illustrates:Footnote 4

(1) Superstar, nouveauté du label américain Femme chocolat, 100% black, [. . .]. (31 October 2007)

(2) Quatre fillettes black d'une rue voisine regardaient bouche bée la vidéo de Fionna Banner. . . (12 October 2009)

Furthermore, the context (pragmatic, syntactic, etc.) in which the borrowed forms appear was initially hypothesized as a possible factor for promoting or refraining inflection. Close examination, however, reveals that few collocation-derived constraints or serial effects could be identified.

This morphological investigation in the press produced a few adjustments to the three groups of adjectival anglicisms originally based on the inflectional status provided by the PR. Table 1 records the counts by inflected/bare forms in the final adjusted groups. Although overt inflection is the most regular pattern, the bare forms represent a significant sub-corpus of 24%.

Table 1 Inflectional patterns of English adjectives

The Appendix contains the complete collection of adjectival anglicisms listed in the Petit Robert 2010. Variants of a same adjective are recorded as separate entries when they yield distinct morphological patterns in compliance with the findings of this study. For instance, people and its variants pipole and pipeule represent three different entries because they display different pluralization patterns in usage (see constraint in 6.1.3).

4 ENGLISH-ORIGIN: A THORNY ETYMOLOGICAL LABEL

Anglicisms in standard French result from ‘distant’ contact with English (Loveday's terminology, Reference Loveday1996). In such a setting, the members of the recipient language community are not characteristically bilingual, even though some are, and the linguistic contact outcome is thereupon limited to lexical borrowing, especially from American English channeled through the mass media (Winford, Reference Winford2003). This level of contact determines the types of borrowings produced and the associated linguistic processes used to create them. It is useful to refine the etymological label English in the Petit Robert because it is a cover term for heterogeneous types of anglicisms and, more significantly for this research, each type influences the degree of morphological integration of adjectives. The following classification is strictly tailored to the list of adjectives whose entry in the PR includes an English etymon. Researchers have designed various typologies for English borrowed words for different purposes (Pergnier, Reference Pergnier1989; Picone, Reference Picone1996). I identified eight categories that I then grouped according to their pluralization behavior: members of types (A-E) systematically follow French morphology and will be succinctly discussed in section 5, members of type (F) systematically reject it, and members of types (G-H) may occur inflected, uninflected, or variably in the plural and will be closely investigated in section 6.

Types (A-E): native pluralization behavior

(A) Classicalisms. Many borrowed English adjectives are, in fact, Latinate (e.g., French insane < English insane < Latin insanus) or neo-Greek (e.g., French miocène < English miocene < Greek meion and kainos), hence their form or pronunciation may have nothing English (Görlach, Reference Görlach2001: xix).

(B) Reborrowings. Other English words originally borrowed from French were reborrowed by French in such altered form that their etymology becomes untraceable (‘allers-retours,’ Walter, Reference Walter1997: 181). For example, the noun scout, which produced the adjective scout, is the abbreviated form of the English compound boy-scout whose second constituent comes from Old French escoute.

(C) Calques. Calques represent a more subtle English source, for they are French word(s) literally replicating an English model (e.g., ouest-allemand < West German). The adjectival ouest-allemand echoes the synthetic English West German vs. the analytic French allemand de l'Ouest.

(D) Loanblends. Haugen's loanblends (Reference Haugen1950, Reference Haugen1953) refer to hybrid forms with fully transferred meaning but partially transferred form. Typically, native derivational processes are applied to English-origin forms to create new words: an example of suffixation is provided by the adjective coolos (< English adjective cool + French informal suffix –os).

(E) Probable anglicisms. The dictionary records the English origin of a handful of adjectives as only plausible (e.g., implosive, tribal).

Type (F): non-native pluralization behavior

(F) Pseudo-anglicisms. These (original) formations are English morphemes which acquired a new meaning exclusive to French, sometimes combined with a change of grammatical class. The adjectival pseudo-anglicisms attested in French all derive from borrowed nouns: new-look ‘innovative,’ hype ‘hip,’ speed ‘hyper,’ and people ‘lurid, celebrity-focused’ (e.g., feuilleton people). In a book chapter on lexical changes for the period 1945–2000, Humbley (Reference Humbley, Antoine and Cerquiglini2000: 83) reports on a neological feature of informal French consisting of coining new words by using already existing words and changing their grammatical class (e.g., noun rat < colloquial adjective rat).

Types (G-H): variable pluralization behavior

(G) Direct borrowings. The English source of a group of adjectives is readily identifiable because their original form remains intact while their meaning was either fully transferred (e.g., tory, punk) or underwent a change in the borrowing process, such as semantic restriction (e.g., cheap refers only to mediocre quality in French).

(H) Other-language anglicisms. English served as a channel for words borrowed by French from other languages. The adjectives kaki and swahili whose origin is Hindustani and Arabic, respectively, entered the French language through English.

5 INFLECTION-FACILITATING CONDITIONS

The initial step in the morphological study of adjectival anglicisms consisted of accounting for how regularly-inflected adjectives differ from seemingly irregularly uninflected ones. Table 2 summarizes the five categories of adjectives that adhere to French morphological patterns. The examination of this sub-corpus produced three major groups, each representing an inflection-facilitating condition.

Table 2 Summary of borrowing types that follow native pluralization behavior

5.1 Similar morphemes in French and English

This condition includes types A-C of the classification as well as orthographically adapted anglicisms regardless of their type. It is not surprising that these adjectives follow native pluralization rules, as they are not felt to be English (e.g., English borrowed primal from Latin). Most of them have long been orthographically and/or phonetically adapted to the French language, to the extent that their English etyma cannot readily be recognized (e.g., compétitif, végétarien). Walter (Reference Walter1997: 192) points out the well-known mask worn by many anglicisms: ‘Tous les emprunts ne disent pas leur nom.’ Orthographic adaptation systematically triggers morphological integration. The correlation is even more evident with the case of adjectives that accept two graphemic forms. The English select and gay, for instance, occur both inflected and uninflected in their original shape, but they always take inflection when gallicized, via the simple addition of an accent for sélect or a reformed ending for gai. Other adjectives receive a playful orthography (e.g., angliche (1861) < English; variants people/pipeule/pipole (1988) < people). This last adaptation in spelling/pronunciation reveals borrowing to be an artful practice popularized by, especially, Queneau (e.g., Zazie dans le métro, 1959: bloudjinnzes < blue-jeans; cornède bif < corned-beef).

5.2 Loanblends

This group corresponds to type D of the classification. Speakers may reshape and transform foreign words while adopting them: ‘It would appear that the composition of lexical entries can be manipulated and rearranged in a variety of ways to produce these outcomes of contact’ (Winford, Reference Winford2003: 42). Loanblends demonstrate that the word-creation technique that is borrowing (external matrix) does not ‘threaten’ the French language, because the borrowed forms are then regulated by native word creation techniques (internal matrices). For example, the adjectives speedé (< speed– + –é) and folkeux (< folk– + –eux) illustrate the process of native affixation to borrowed stems. Compliance with French inflectional patterns is to be expected in these cases because the plural marker is attached to native suffixes.

5.3 Age of borrowings

Adjectival anglicisms which have retained their obviously original English spelling and yet conform to French morphological conventions may have a long history in the lexicon of French. This is the case of inflected yankee (des accents yankees), a borrowed form which entered the French language in 1776. Yet the adjective black is still found uninflected, although rarely, despite joining the French lexicon in 1790. For informative purposes mainly, the date of attestation of each English-origin adjective is indicated in the Appendix. Frequency of use and dispersion are two proven metrics of the degree of entrenchment of borrowings into the lexicon (Chesley and Baayen, Reference Chesley and Baayen2010); more accurately, a borrowing's dispersion, ‘the number of text chunks a word occurs in if a text is divided into several subparts’ (p. 1344) is a more effective variable than frequency, as frequency is relevant only to the extent that it is correlated with dispersion. Although frequency of use will be provided for a few adjectival forms, this paper does not attempt to measure this variable.

6 INFLECTION-INHIBITING CONSTRAINTS

Lack of inflection on borrowed adjectives has been reported only cursorily. Pergnier (Reference Pergnier1989) does not treat the pluralization of either nouns or adjectives in his morphosyntactic account of anglicisms. In fact, he even claims that the morphological integration of anglicisms is an issue of minimal interest. Battye, Hintze, and Rowlett (Reference Battye, Hintze and Rowlett2000: 129) point out the small set of morphologically invariant adjectives in French without explaining, however, why these adjectives fail to adopt native morphology in the borrowing process: ‘Some, for example standard, chic and snob, are borrowings from other languages which have not been regularised.’ Bidermann-Pasques and Humbley (Reference Bidermann-Pasques and Humbley1995: 59) offer a brief restatement of the inflectional status of English adjectives provided in dictionaries: ‘Selon les dictionnaires, les adjectifs de forme anglo-saxonne seraient invariables. Or, nous avons relevé dans le corpus de Libération quelques cas d'accord du pluriel pour les adjectifs black, gay, smart et cool.’ Yet the 1993 edition of the Petit Robert records black as an adjective that regularly inflects in the plural. In a database (starting in 1987) from Libération, Bidermann-Pasques and Humbley observed that black and gay occur both inflected and uninflected, although overt inflection is a rare pattern. Contemporary press data from Libération (2006–2010) indicate reverse patterns in the direction of stabilization—these two adjectives are now mostly integrated. Grevisse (Reference Grevisse and Goosse2008: 721) lists examples of numerous adjectives borrowed ‘tels quels’ that tend to remain bare (e.g., Japanese zen, German mastoc, English open). The observation that these adjectives are directly borrowed forms is approximate because the forms bobo and addict were also borrowed intact yet they behave like native adjectives when pluralized. I examined members of types F-H of the classification, 84 uninflected adjectives and 11 variable ones, and identified two main explanations that account for their resistance to overt inflection: one relates to recognition of a non-native trait, and the other involves inflection-inhibiting constraints that also apply to native adjectives. Table 3 summarizes the constraints reported for each explanation.

6.1 Incorporation of non-native traits

The English-origin adjectives of this set introduced into French non-native traits, either orthographic, or phonological, or both.

6.1.1 Adjectives ending in −y

A group of 15 dictionary-attested English adjectives end in −y: baby, baggy, cockney, cosy, country, destroy, dry, flashy, funky, gay, groggy, hippy,Footnote 5jazzy, sexy, and tory. Other than the 15 items of English origin listed above, the Hebrew goy, and the learned term epoxy, adjectives ending in y do not occur in French. Except for the inflected cockney and tory and the variable gay, they are characterized by non-adaptation to French inflectional paradigms. The forms cockney and tory are the oldest of the group; their entry into the French language dates from 1750 and 1704, respectively. Their long presence in the French lexicon certainly facilitated their adoption of a native plural marking (des accents cockneys, des figures tories). The only adjectival plural form of tory in the Libération corpus is patterned on the English tories (vs. torys), which confirms that a final −y may hinder pluralization. The adjective gay is recorded as uninflected in the Petit Robert but inflected in the Petit Larousse, while a query in Libération reflects the gap between the two dictionaries by showing variable behavior, though overt agreement marking is the norm; on a sample of 86 contextually plural adjectival forms,Footnote 6 the inflection rate for gay is over 85%. No contextual constraint seems to account for inhibiting inflection; for example, both inflected and uninflected forms occur in similar contexts with pairs like mariages gays/mariages gay and bars gays/bars gay. The adjective gay is the most frequently used of the series in the newspaper, and frequency of usage may very plausibly contribute to a higher degree of integration. An analogy-motivated factor may also serve as a facilitator with the already available adjectival gai in the French lexicon. In fact, the English gay was orthographically adapted as gai, though this form is rarely used.

6.1.2 Realization of usually-silent final consonants

A consonant not followed by schwa at the end of French words is not usually pronounced (e.g., trouillard /trujaʀ/). In contrast, realization of the final consonant is the norm in English (e.g., hard /hɑrd/). The preservation of the original pronunciation of the final consonant is a shared trait of a group of 25 uninflected English-origin adjectives. The analysis that follows demonstrates that the transfer of this English phonological feature tends to hinder the affixation of a native plural marking (e.g., des yaourts light ‘low-fat yogurts’). As a reference, I used the lists of final consonant-letters that are generally silent in French, including exceptions, presented in Battye, Hintze, and Rowlett (Reference Battye, Hintze and Rowlett2000: 74–77). The English adjectives investigated here end in the consonants −t, −p, −d, −c/sh, −n, and −(in)g.

A final −t is silent in French but for a few forms, notably foreign words and words ending in –ct. Inflection is blocked for the adjectival anglicisms whose final −t is pronounced (antitrust, hot, let, light, net, smart, soft, and spot), except for the form scout, which regularly pluralizes. Unlike the other adjectives of the series, scout may receive a feminine ending (although gender marking is not systematic) and has produced the derived forms scoutisme and scoutesse, which are transparent indications that the English form is treated like any other adjective by the morphology of the French language. The English adjectives addict, compact, and select may receive inflection, because the cluster –ct in final position of French words features a realized /t/ (e.g., strict /stʀrikt/, correct kɔʀɛkt/). This phonological convergence between the two languages in contact eases morphological integration and provides evidence for analogy-based morphology.

Other final consonants also exhibit inflection-blocking behavior. Borrowings and interjections are the only words whose final −p can be pronounced in French. The adjectival anglicisms ending with a realized p reject native inflection: cheap, top, and wasp. Likewise, d is characteristically silent in final position except for borrowings, hence the lack of a plural marking for the English forms compound, hard, speed, and underground. Adjectives ending in –ch/sh in French are all borrowed forms, including the German kitsch or kitch and the English amish, cash (‘blunt’), scratch, trash, and yiddish. This orthographic consonant cluster rejects plural suffixation.

In French, the combination of a vowel followed by an n characteristically produces a nasal vowel (e.g., bigouden, paysan). Two borrowed English adjectives ending with this cluster, clean and open, preserve their original pronunciation, which results in the blocking of plural suffixation. Adjectives ending in –ean (/in/) and those ending in –en (/en/) do not occur in French except for these English adjectives and the Japanese zen, which is also invariable (des maîtres zen). Three adjectives share the final –ing, namely revolving, sterling, and shocking, triggering the use of the phoneme /ŋ/ that does not belong to the phonemic inventory of French. This non-native ending constitutes another inflection inhibitor.

6.1.3 Native-like ending combined with a non-native phonemic-graphemic correspondence

Six groups of adjectival anglicisms share endings that are permissible in French, i.e., usually-realized final consonants (Battye, Hintze, and Rowlett, Reference Battye, Hintze and Rowlett2000: 74–77) plus the vowel −e, so these endings might be expected to receive a plural morpheme. Nevertheless, these words also share phonemic-orthographic correspondences that strikingly fail to conform to those of French and may as a result obstruct morphological integration.

6.1.4 Adjectives ending with the usually pronounced final consonants −l, −f, and −k

The final consonants −l and −f are commonly realized in French and accept a plural marking (des pianistes mariols productifs). Unlike the morphogically integrated Italian-origin mariol, for example, the invariable English forms cool and waterproof possess a phonological and orthographical interplay that does not adhere to French conventions. This non-native interplay seems to prevent complete integration with blocking of plural suffixation. Adjectives ending in −k in French include exclusively foreign borrowings. They all accept inflection (des pianistes kanaks < Polynesian; des pianistes bolcheviks < Russian) with the exception of the English punk and black, which represent more complex cases for displaying variation—des pianistes blacks or des pianistes black and des pianistes funks or des pianistes funk. In their Libération corpus, Bidermann and Humbley (Reference Bidermann-Pasques and Humbley1995: 59) report that the adjective black is rarely found inflected. In a later sample from Libération (years 2006–2010), I recorded the adjective black as occurring predominantly inflected in the plural (30 inflected forms vs. 3 uninflected forms). The expression black blanc beur, patterned on bleu blanc rouge to designate a multi-ethnic France, and highly popularized in the 1990s, may have contributed to the increased morphological integration of black. Punk is the other adjective ending in −k whose inflectional behavior varies. In a Libération sample composed of 65 contextually plural occurrences of adjectival punk, the form is used bare in over 75% of cases. Two constraints associated with compounding and ellipsis may inhibit inflection on punk; these constraints are presented below. Seventeen of the 65 occurrences are part of an adjectival compound (e.g., pré-punk, punk rock), and inflection is consistently blocked for these compound constructions. A category of uninflected adjectives in the dictionary corpus refers to music styles (e.g., des airs rock; des airs funk). These adjectives will be analyzed as elliptical forms, and ellipsis will justify the absence of plural marking (e.g., des airs (de musique/de style) rock; des airs (de musique/de style) funk). By analogy, the adjective punk may be treated as such since the term semantically includes a musical style, which would explain its large number of bare occurrences in the press. However, unlike the other English elliptical forms that refer to music genres, the adjective punk is derived from a noun defined as a social movement and so is not restricted to music. This broader definition may favor morphological integration with the use of punk in more semantic categories, as these two contrastive examples illustrate:

(3) Le hip hop taille XXL. . . Avec Matthew, nous avons le même ingénieur du son et les sonorités punk, folk ou rock ne sont pas pour me déplaire. (30 June 2008)

(4) Nous sommes plus “hérétiques” qu'eux par rapport à la modernité occidentale, plus “punks”, plus pirates, plus “queer”, plus radicalement pragmatiques puisque nous contrôlons les moyens de production grâce aux ordinateurs et à Internet. (10 June 2008)

In the first instance of punk (3), the form strictly refers to music, and the ellipsis hypothesis is emphasized by the analogously uninflected folk and rock. They can all be treated as elliptical forms: les sonorités punk, folk ou rock derives from les sonorités DE MUSIQUE punk/folk/rock ou les sonorités de STYLE MUSICAL punk/funk/rock. In the second example (4), the inflected adjectival punk has a broader, social meaning. This semantic constraint is not categorical but tends to facilitate integration. As a noun, punk is polysemous referring to animates and has even produced the feminine derived form punkette. The derivation of English forms with native affixes must be considered a solid indicator of integration.

6.1.5 Adjectives ending in −e

Although the vowel −e constitutes a proper receiver of a plural morpheme in French, the two faux-anglicisms people, derived and shortened from people journalism, and hype do not accept it. As a noun, people can be used both as an uninflected plural (les people) and as a singular form referring to a single individual (un/une people) or a social group (le people). The former French use of people in the singular clearly indicates that it no longer conforms to English, in which people cannot have a single person as a referent. The form people can also appear playfully written pipeule or pipole à la Queneau, and each of these phonetically spelled forms displays a variable inflectional status in online press usage: des magazines pipeule/pipole and des magazines pipeules/pipoles. The uninflected form is likely patterned on the original English people (5), whereas the inflected form follows French morphology based on a gallicized orthography (6), which further signals that a foreign orthography-phonology relationship blocks inflection.

(5) Ce jeune homme au visage de Cherokee a longtemps vécu hors de portée des radars people, ce qui lui confère une fraîcheur rare. (5 February 2011)

(6) En 1891, en effet, Jules Huret avait inventé le journalisme spécial «C'est quoi la littérature ?» en demandant aux auteurs pipoles de son temps ce qu'ils pensaient de la mort du naturalisme [..]. (10 February 2011)

Pipole and pipeule may have been playfully coined, but their productivity in terms of serving as a basis for coining new derived forms such as demi-pipole, pipeulaire, and pileulerie may indicate a sign of deeper integration into the lexicon. The form people, however, has not yielded derived forms in French. This analysis is reinforced by the other bare faux-anglicism hype (des artistes hype) whose phoneme-grapheme correspondence also deviates from French though the −e ending might be expected to accept a plural suffix.

6.2 Uninflected English adjectives complying with French morphology

Section 2 showed that resistance to inflection is permissible in French. In fact, the inflection-inhibiting constraints that apply to native adjectives may also apply to English-origin adjectives as the following section will demonstrate.

6.2.1 Prepositions

The PR records six adjectivized English prepositions: in (‘trendy’), off, out (‘outdated’), knock-out, made in, and stand-by. They do not receive inflection even when used adjectivally (e.g., les sièges avant), in compliance with the rule for French prepositions, an invariable word class. The absence of morphology on English-origin prepositions is also reflected in the inflectional pattern of compound nouns whose second constituent is a preposition (e.g, des knock-out cf. English some knock-outs). Whether adjectivized or constituents of a nominal compound, English-origing prepositions follow French morphological rules and accordingly remain invariable.

6.2.2 Color adjectives

An analogy-motivated inflectional deviation includes the adjectival anglicisms of color auburn and kaki (des reflets auburn, des uniformes kaki) both of which pattern on other invariable color adjectives in French, especially noun-based adjectives (des teintes acajou, fuchsia et noisette), and thus remain bare in the plural. This constraint also emerges from native morphological conventions.

6.2.3 Ellipsis

A series of uninflected adjectives derive from non-count nouns that refer to music genres–disco, folk, funk, grunge, hip-hop, pop, reggae, rock, soul, techno, and yé-yé. These non-count nouns are used, by definition, in the singular. Their adjectivized forms can be interpreted as resulting from an ellipsis: des notes funk, for example, is a construction derived from des notes DE MUSIQUE funk ou DE STYLE funk, in which funk defines the singular noun musique or style. Used elliptically, the adjectival funk does not receive inflection, for its stands for the singular phrase de musique funk or de style funk. In the press, all the following constructions are used, from the most frequent to the least frequent: des notes funk < des notes de funk < des notes de musique funk. In addition to adjectives referring to music genres, two bare adjectives, also derived from mass nouns, refer to a novel/film genre—gore—and two fashion styles—glamour and sportwear/sportswear— and may receive the same ellipsis-founded analysis (e.g., des robes glamour < des robes DE STYLE glamour).

Ellipsis as a plausible candidate for inhibiting inflection is strengthened by two other arguments. First, the contrastive pluralization behavior of the abbreviated French techno (< technologique) and the abbreviated English techno (< technological): les lycéens généraux et technos (Libération, 06 October 2009) vs. des soirées techno (Libération, 30 October 2009). In the first example, techno receives inflection as a regular native adjective, whereas in the second example, techno is used elliptically as inferring the singular construction de musique techno(logique), hence its bare adjectival status. Second, certain of these English adjectival forms referring to music styles take French affixes (folkeux (adj.), rapper (v.)), and the process of deriving foreign forms is a sure indicator of integration, so all these adjectival forms could potentially receive a plural marker, if not blocked by the ellipsis constraint.

Four other bare items may be interpreted as elliptical forms in French: autoreverse (un magnétophone autoreverse < un magnétphone À SYSTÈME autoreverse); live (des concerts live < des concerts EN live); cantilever (des ponts cantilever < des ponts À POUTRES cantilever); nord (les portes nord < les portes AU nord). On a semantic level, these forms can be read as metonymic with change of grammatical category (n. → adj.) through ellipsis, which is a reported French lexical practice (Picoche, Reference Picoche1986: 85–87).

6.2.4 Initialisms

The Petit Robert records five initialisms used as adjectives: F.O.B. (Free On Board), H.L.A. (Human Leucocyte Antigen), O.K. (oll korrect < alteration of all correct), S.A.E. (Society of Automotive Engineers), and C.I.F. (Cost, Insurance and Freight). In compliance with a general rule in the French language, capitalized initialisms constitute a type of abbreviation that does not accept a plural marking (e.g., les cités HLM [Habitation à Loyer Modéré]; de jeunes mamans très NAP [Neuilly, Auteuil, Passy]). Mortureux (Reference Mortureux2001) attributes the increasing use of acronyms in French to the influence of English.

6.2.5 Compound adjectives

The morphological description of compound words in French is notoriously complex (Brousseau and Nikiema, Reference Brousseau and Nikiema2001): number agreement depends on the word class of each constituent, and, more intricately, on the relation between these constituents. Variable forms (casse-pied or casse-pieds) circulate as a result of native speakers’ hesitation regarding their plural marking. The English-origin compound adjectives used in French are all used bare: after-shave, free-lance, extra-dry or extradry, fair-play, in-bord, has been, hi-fi, new-look, non-stop, offshore, tip-top, and top secret. It is plausible that French speakers cannot identify the word class of the constituents and consequently the recipient(s) of inflection, and so treat all adjectival compounds as invariable forms as a simplification process. In a way, this treatment of adjectival anglicisms erases the morphological complexity and irregularities of the native adjectival compounding system. Regularization is a reported pattern of linguistic contact, as is, more generally, the correlation between borrowing and processes of simplification (Winford, Reference Winford2003: 52; Trudgill, Reference Trudgill and Hickey2010: 306–309).

This morphological simplification can apply to the compound adjectives of English-origin wah-wah and bling-bling, with the specification that they have in common an onomatopoeic origin subject to reduplication. The combined factors of compounding and reduplication may be at play in inhibiting inflection. Native forms derived from onomatopoeic (bof) and reduplicative (olé olé, gnangnan) processes also typically reject inflection (Grevisse, Reference Grevisse and Goosse2008: 726). An explanation is that the grammatical category of the constituent is difficult to determine. To a great extent, these compound adjectives resemble frozen expressions. As further evidence, both adjectival (7) and nominal (8) reduplicative forms reject inflection:

(7) Cette exposition ne ruisselle pas de lumières criardes, ne joue pas les projecteurs bling-bling. (17 January 2011)

(8) Exit le charme discret de la bourgeoisie, bobos et bling-bling ont montré la voie. (27 October 2010)

6.2.6 Prefix-analyzed adjectives

According to the Petit Robert, the uninflected adjective afro, an abbreviation of the compound afro-American, restrictedly designates a type of hairstyle in French (boucles afro). Yet in press usage the adjective also refers to its original broader lexical meaning of pertaining to Afro-Americans (soirées afro, sons afro). The prefix/compound element afro- is productive in French (afro-chrétien, afro-reggae), and consequently even when used adjectivally, which is less frequent than in compound constructions, it may still be analyzed as a prefix, a bound morpheme, and thus an invariable form. The uninflected adjectival vidéo (des caméras vidéo), an exceptional form as a Latin verbal form that English channeled to French, may be similarly treated. Like afro, vidéo is used in word formation as a common invariable prefix/compound base (vidéo-informatique, vidéophile), and may also be interpreted as such in adjectival uses, which would justify its lack of plural marking.

Table 3 Summary of inflection inhibitors

7 ADJECTIVES VS. NOUNS

Some of these bare English adjectives are also nouns, but such nouns, puzzlingly, do follow French pluralization patterns, as illustrated by the form baggy, used as an uninflected adjective (9) vs. an inflected noun (10) in plural contexts from Libération excerpts:

(9) Lassé de traîner ses pantalons baggy au sein des groupes de hip-hop [. . .], ce jeune de 26 ans emprunte 10 000 dirhams (1 000 euros) pour produire, il y a trois ans, son album solo Mghraba’ tal mout (6 September 2007)

(10) Blacks stylés venus du Blanc-Mesnil (Seine-Saint-Denis), baggys qui s’écrasent juste ce qu'il faut sur des tennis immaculées, Jonathan et Molière connaissent Misericordia depuis l'hiver dernier. (22 September 2006)

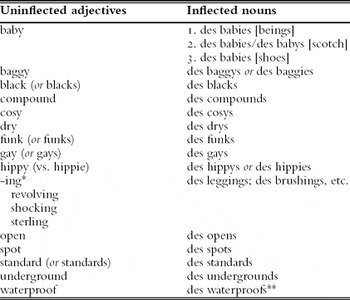

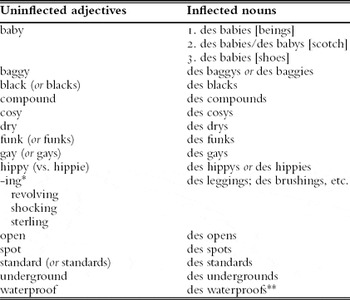

Table 4 records the English adjectives with their nominal counterpart and points out the contrasting pluralization behavior of the two word classes. The opposition between inflected nouns and uninflected adjectives is interpreted as evidence that the difference in word class is responsible for a different morphological behavior in the borrowing process. The analysis that follows proposes an interpretation for this contrastive treatment based on the grammatical feature of gender, and more specifically on a constraint on affix ordering.

Table 4 Status of plural adjectives and their nominal counterpart

*The three adjectives with an –ing suffix that are listed above do not have a nominal counterpart, but the French lexicon contains many English-origin nouns ending in –ing (Spence, 1991; Picone, Reference Picone1996). They all take a plural marking (des leggings, des brushings).

**The inflected noun waterproof is listed in the Petit Robert (but not in the Petit Larousse) as referring to a raincoat, but I could not find any examples circulating because this term has become obsolete (Görlach, Reference Görlach2001: 344–345).

While both adjectives and nouns are marked for plural in French, a standard divergence between these two word classes is the attribution of gender agreement. The gender of a noun is an inherent property, whereas the gender of an adjective is assigned via the gender of the noun it qualifies. It is well-documented that loan nouns tend to take the unmarked gender of the host language, i.e., the masculine for Romance languages (Clyne, Reference Clyne2003: 147). Accordingly, English borrowed nouns are (mostly) masculine (e.g., un brownie, un cosy, un slim ‘a pair of slim fitting pants’) and thus do not require a feminine agreement morpheme to be morphologically integrated into French. In contrast, adjectives require both a masculine and a feminine form, and this complex morphological condition may prevent native affixes from attaching to non-native adjectival stems.

In section 6, the recognition of a non-native trait is attributed responsibility for blocking number agreement. In fact, before blocking number, it blocks gender agreement, which is the first inflectional suffix attached in orthography to the adjectival root, number being second, as illustrated in the phrase les chansons folkeuses: folk –euse (1 feminine) –s (2 plural). Subsequently, the incorporation of a non-native feature into French triggers the incorporation of a non-native morphological pattern, i.e., adjectives remain unmarked in (1) gender and (2) number, as exemplified with the −y ending adjective baggy: une veste *baggye; des vestes *baggyes; des vestes baggy vs. des baggys (n.). The gist of this proposal derives from a constraint on affix ordering on non-native bases. This phenomenon may extend to borrowed adjectives in general vs. adjectival anglicisms, exclusively. For example, the adjective vaudou, borrowed from a Benin language, occurs variably with and without native feminine and plural marking, as these Libération samples exemplify: (f.) une poupé vaudou vs. sa mandoline vaudou; (f. pl.) distorsions vaudou vs. fins vaudoues. It is then expected that no categorical feature blocks inflection, and an empirical study would be useful in refining these provisional findings.

The contrastive morphological pattern of English borrowed nouns and adjectives also suggests that because French adjectives carry both number and gender morphemes, they are morphologically more complex to integrate (from one language into another) than are nouns. As a consequence, the use of adjectival bare forms can be analyzed as an avoidance strategy for dealing with complex, marked features. This strategy echoes the loss of redundancy reported in linguistic contact (Trudgill, Reference Trudgill and Hickey2010), as more than one signal can convey feminine and plural in French. On a more general level, this phenomenon could explain why nouns are more borrowed than adjectives in hierarchies of borrowability (e.g., Muysken, Reference Muysken, Highfield and Valdman1981: 62), distributions of parts of speech in borrowed lexicon.

8 CONCLUSION

This study is the first to identify and analyze inflection-inhibiting constraints for French dictionary-sanctioned adjectives of English origin. The constraints partially verify the hypothesis that the inflectional behavior of adjectival anglicisms is governed by borrowing rules that differ from those that characterize native French words. The group of uninflected and variable adjectives does violate the standard rule of adjective agreement in French, yet the conditions that block inflection are French-derived (summarized in Table 3). Whether due to recognition of non-native traits or to direct compliance with French morphological conventions, the ‘deviant’ behavior of these borrowed (external) adjectives is not dictated by borrowing rules per se but by French (internal) rules and conditions. Because the corpus of adjectival anglicisms is relatively small, it does not justify a categorical validation of certain constraints, especially and evidently those that govern only a handful of cases. These constraints, however, represent a foundation for further investigation of a sub-phenomenon of French morphology that has been ignored and could be tested on other corpora.

APPENDIX: LIST OF ENGLISH-ORIGIN ADJECTIVES IN THE PETIT ROBERT 2010

This alphabetical list is composed of the complete dictionary collection of 395 adjectival anglicisms. Uninflected adjectives are emboldened, and the symbol (V) follows variable adjectives. The date of attestation is also specified. However, for certain adjectives, especially calques, the dictionary does not provide the date.