Monuments and memories

On a stroll uphill from the worn-down old centre of Kupang, the hub of West Timor, the visitor will notice a statue of a horseman armed with a pistol, riding his steed in the middle of a heavily trafficked street. This man is Nai Sobe Sonba’i III, a leader of the highland Timorese kingdom of Sonba’i who was captured by collaborators of the Dutch in 1906 and died under surveillance in 1922.Footnote 1 While the bloody conquest of Badung on Bali in the same year, and the contemporary conclusion of the Aceh War, are emblematic markers of anti-colonial resistance, the horseman on the Kupang thoroughfare, erected in 1976, is only locally known.Footnote 2 As an example of indigenous forms of opposition that met the expanding colonial state in the early twentieth century, his performance nevertheless is if considerable interest. His role as an Indonesian hero stands in stark contrast with colonial documents that portray him as a troublemaker and an anachronism in the system of “peace and order” that the Dutch colonial state ostensibly tried to impose. The present article will apply a historiographical perspective on this by scrutinizing the claims of indigenous voices about the event and asking how they qualify and even challenge the contemporary and near-contemporary colonial sources. This is complicated by the nature of the sources: Timorese societies were traditionally nonliterate and left few written records before the end of colonial rule, while the colonial archive offers relatively abundant materials. Thus, the basic question is who gets to write colonial history, addressing two partly overlapping issues: how to find a balance between colonial and indigenous voices, and what oral tradition and oral history may add to our understanding of historical processes. How do the oral informers try to make sense of a past historical landscape long after the events they purport to relate?

Image 1 The Sonba’i monument in Kupang, erected in 1976.

In the last three or four decades, a substantial literature has surfaced on the issue of problematizing the colonial archive and demonstrating how elliptic power relations have shaped historical conventions. One is reminded of Reference SpivakGayatri Spivak’s famous question whether the subaltern can speak, the answer to which was pessimistic. This is not only due to the lack of sources but an unwillingness to listen to alternative voices in the first place. While many people over the years have tried to write the interests of the subaltern into historical narratives, they tend to speak for rather than with those on the subordinated side. To quote another cultural critic, “the cry of the victims of colonialism was ultimately the cry to be heard in another language—which would be unknown both to the colonizer and the anti-colonial movements that he had bred and domesticated.”Footnote 3 As will be seen from the present study, these concerns apply in the highest degree to our Timorese case.

Studies of the Southeast Asian past have occasionally drawn inspiration from postmodern and postcolonial perspectives, incorporating elements of literary theory in historical research. A consequence of this has been to question the truth of the colonial records, since they set the agenda for the historian’s research, and even dictate the questions. This raises doubts whether primary sources in a general sense can form the basis of truth claims about the past. In this view, all sorts of primary sources may be regarded as texts, which must be scrutinized with regard to consistency and their relationship to other data.Footnote 4 The writing of colonial sources is associated with a degree of professionalism; the texts were not intended for wider dissemination, and are therefore perhaps less prone to embellishment. Nevertheless, they have been found to be less disinterested than their sober style often suggests; then, too, there is the obvious question about how much their authors actually understood of local society. While, for example, the verbose Dutch memorandums of regional affairs, memories van overgave, contain much material about recent history and ethnography, one is reminded of Oscar Salemink’s verdict of ethnographic work in another part of Southeast Asia, “that economic, political and military interests within a specific historical context condition ethnographic practice.”Footnote 5

Turning to the other side, what knowledge can we expect to gain from oral sources? Here we must distinguish between oral history, based on interviews with people narrating their life experiences (or contemporary events they heard about), and oral tradition, in which information passes from mouth to mouth. Large areas of Southeast Asia including Timor lack indigenous written sources until a comparatively recent time, meaning that techniques for transferring data orally have evolved, for example via appointed custodians of tradition or in the form of poetic narratives. Researchers of the African past have drawn attention to oral history and tradition and emphasized the need to analyse the circumstances of the performer and performance. Who is entitled to speak and make claims about the past, and in what situations are the data narrated? The evaluation of the data depends on a triangulation of categories of sources—variants of the oral narratives, linguistic data, archaeology, anthropology, whatever external written narratives there may be. Historical tradition may be more stable in tightly organized polities—Benin, the Ashanti Kingdom—than in stateless societies or societies with a weak centre, although this depends on a number of factors and is not always the case. Comparisons with written data, often of colonial origin, may point out fascinating confluences, such as persons in stories and pedigrees occurring in written documents. However, the dissimilarities are just as important to note, indicating the differences in outlook and ideas of what was worth remembering—and how tradition was renegotiated and reinvented to provide a rationale for the present.Footnote 6

The use of oral tradition in Southeast Asian and Australian contexts has been demonstrated by a few scholars, often working in the borderland between history and anthropology. James Fox has studied genealogies from Rote, west of Timor, which often display a degree of factual reliability back to at least the seventeenth century. From Fox’s research, it appears that certain stock names and events have become petrified, forming the particles of which new (and strictly speaking unhistorical) narratives are constructed.Footnote 7 In another context, Chatthip Nartsupha has shown how oral data adds to our knowledge of peasant movements in Thai history, even describing a peasant rebellion in around 1895 not known from written documents.Footnote 8 But oral tradition can also problematize conventional Western notions of space and time. Thus, Minoru Hokkari has analysed the “dream” stories preserved by the Gurindji people of Australia, which are not conventionally factual, being characterized by “experiential truthfulness” rather than “historical truth”—in other words containing experiences of past conditions in a truthful way.Footnote 9

Such considerations are highly interesting when studying the Sonba’i resistance of 1905–1906 which occurred during a time when utterly dramatic political changes took place on Timor, and in much of maritime Southeast Asia.Footnote 10 The centrality of the Sonba’i clan in Timorese history made the colonial conquest a decisive event, but the very limited material resources of Nai Sobe Sonba’i rendered his act of resistance somewhat irrelevant and despicable in the Dutch colonial reports. The present study scrutinizes the war via different categories of sources, where the aim is on the one hand to explore the range of possibilities of what happened in view of the representations in the colonial archive and indigenous stories, and on the other hand to explore how the sources work, how they are related to shifting ideologies and power relations. To achieve these aims I will first provide a brief background to the place of Sonba’i in Timorese history. Next, I will address the problem of using oral accounts in the context of a preliterate society that is incorporated in a postcolonial nation. I will then consider the origins, course, and outcomes of the conflict by juxtaposing written documentary and oral data. Finally, the consequences of the similarities and divergences for our understanding of the Timorese past will be discussed.

Sonba’i—The State that Never Was

To understand the significance of Sonba’i as a symbol of resistance and indigeneity, we must first take a closer look at its impact in precolonial and early colonial Timor. Scholars of early Southeast Asia have employed various terms to capture the structure of precolonial kingdoms, such as “segmentary states,” “contest states,” “galactic polities,” “theatre states,” and “symbolic kingdoms,” all emphasizing the lack of Western-style bureaucratized or executive rule.Footnote 11 As for Timor, Andrew McWilliam has found similarities to the Indianized states in the western part of the archipelago inasmuch as power radiated from an exemplary, ritually laden centre at a diminishing rate. At the same time, the contrast between the Timorese rulers and those of Sumatra, Java, and Bali is obvious. The dilemma was that the larger a polity was built up by a centre, the greater the likelihood that it dissolved into subdomains.Footnote 12 The lack of preconditions for intensive agriculture, and the limited incomes from commerce, rendered the power base of the Timorese lords fragile, and the extensive Sonba’i realm demonstrates this syndrome.

The island had long been politically fragmented in innumerable smaller or larger “kingdoms,” although there was a formal division between Dutch and Portuguese spheres of interest since the 1850s. Apart from a few coastal enclaves such as Kupang, Atapupu, Batugade, and Dili, there was no tight colonial control until the early twentieth century. Towards the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, however, the process of colonial intrusion on the island accelerated. The starting point for the Dutch subordination of “their” part of the island was the deteriorating relations between the administration in Kupang and the ruler of Sonba’i in the interior. Sonba’i was traditionally considered the foremost power in terms of ritual prestige among the Atoni people, although this did not always translate into executive power.Footnote 13 Briefly, society was based on the relationship between genealogical groups, whose headmen (amaf) formed the base of the political hierarchy. A great headman (amaf naek) would represent a subdomain and also function as tobe naek (great custodian of land), bringing harvest gifts to the ruler. Around the ruler were four princely assistant lords (usif), namely Kono, Oematan, Taiboko, and Ebenoni. Symbolic gender had great importance in defining sociopolitical roles: the Sonba’i ruler was “female” (feto) in relation to the usif, who were “male” (mone).

The paramount ruler was known in a Timorese context as neno anan (son of heaven), atupas (he who sleeps, that is, upholds a ritual position), or liurai (surpassing the earth).Footnote 14 Since the seventeenth century, the Europeans termed him emperor (imperador, keizer). The other West Timorese rulers usually related themselves to him genealogically, although he was not their actual overlord, as is sometimes alleged in the literature.Footnote 15 Certain cultural markers indicated people’s inclusion in the Sonba’i sphere: thus the waist-cloths were woven in three fields of which the middle one was white.Footnote 16 A large number of myths and legends related to Sonba’i flourish on Timor, which tends to depict the ruler as a half-god with influence on rainfall and the fertility of the land.Footnote 17 He was considered a junior relative of the Tetun-speaking “dark lord” of Wehali in southern-central Timor, regarded as the navel of the island.Footnote 18 Sonba’i was formally drawn into the Dutch sphere via a contract prepared by the VOC diplomat Paravicini in 1756, together with a host of rajas from Timor, Rote, Savu, Sumba, Solor, and Adonara.Footnote 19

While custom—in an Indonesia-wide context known as adat—place emphasis on the Sonba’i ruler’s position between micro- and macro-cosmos and thus his religious-ritual role, the actual history of the polity is marked by constant strife and schism. Colonial sources enable us to follow at least some outlines of this. The foremost assistant lords of the realm, Kono and Oematan, were sometimes at odds with the ruler, and the same went for a number of minor lords in the Atoni hierarchy. Moreover, the ritual role of the Sonba’i lord did not stop some incumbents from taking an atypically active role. The European-educated Alphonsus Adrianus dominated the highlands of West Timor from 1782 to his death in 1802 and engaged in a long series of petty wars, often using the simmering rivalry between the Dutch and Portuguese to his advantage and keeping beyond effective Dutch control. While relatively successful, he was nevertheless unable to bring about a real state formation.Footnote 20 His son Nai Sobe Sonba’i II was acknowledged in 1808 and had a lengthy rule that lasted until 1867, but he had problems retaining the loyalty of Kono and Oematan. For certain periods, he was almost deserted by the minor lords of the realm, as observed by the naturalist Salomon Müller, who visited the inland in 1829.

About eleven o’clock [on 30 August 1829] we reached the Plain of Neffo, which lies to the north of the great rock Kauniki, which, being the home of the Liurai Nai Sobe, Keizer of Sonba’i, has gained a historical importance.Footnote 21 This ruler was slowly left by all his grandees due to his cruelty, and escaped from his own land several years ago for safety reasons, to this wild rock. . . . It is said that only seven men and thirty women followed him to this lonely and sheer, impenetrable sanctuary, and that they are now busy securing the maintenance of their ruler by working a few maize fields and cultivating vegetables.Footnote 22

Sobe later regained some of his powers, partly through the mediation of the Dutch resident in Kupang.Footnote 23 That did not mean that he controlled the movements of the regional and local lords, some of whom, such as Manubait and Takaip, attacked the Dutch possessions in westernmost Timor on their own accord. There was also a long-standing feud with another powerful Atoni princedom, Amanuban, about the right to harvest sandalwood and beeswax in the border region.Footnote 24 When Sobe eventually died, his prerogatives were disputed between his son Bau Sonba’i and a nephew called Nasu Mollo. The Dutch authorities in Kupang made a contract with Nasu in 1870, possibly since he was the one claimant who was willing to visit Kupang. Later oral tradition referred to Nasu as a “deceiver in the family.”Footnote 25

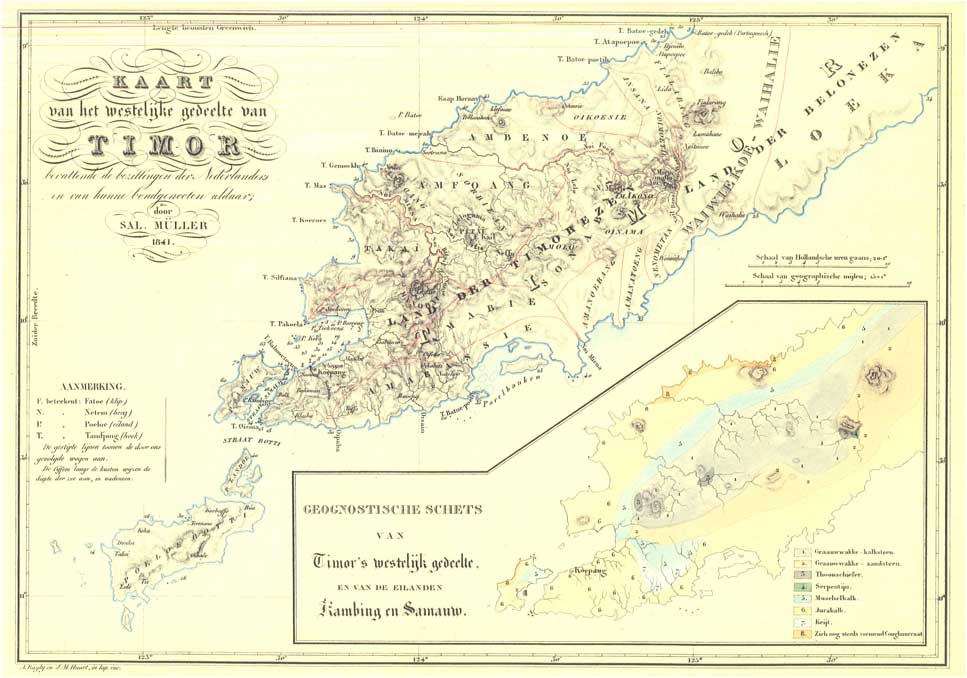

Image 2 A map of West Timor, in Salomon Müller, Reizen en onderzoekingen in den Indischen Archipel (1857).

We have a detailed account of the diplomatic ceremony in colonial Kupang that describes how Nasu and his chiefs were led to a tent under the eyes of a multitude of spectators. They were all dressed in traditional Timorese gear and wore long curly hair bound up with a cord or a piece of cloth. They wore red woollen vests over their upper bodies and a selimut (blanket) over the lower part, and were adorned with red or green parrot’s feathers at the side of their heads. The lords were furthermore furnished with coral necklaces, silver discs, and rings of silver and ivory. Among the retinue were several headhunters, distinguished by their adornment made of goat’s fur. Nasu himself was distinguished by tubes with gold sand that were inserted through his ears.Footnote 26 An economic aspect was there as well: two merchants, T. C. Drysdale, a Briton, and H. Siso made a deal with Nasu to extract gold sand in the Sonba’i realm, something that soon proved entirely impractical.Footnote 27

If the Dutch believed that the impressive ceremony would create ordered conditions in the Timorese highlands they were entirely mistaken, however. When Resident Ecoma Verstege visited the inland in 1875, he reported a complicated situation with two Sonba’i pretenders, disobedient chiefs, and involvement of the raja family in horse theft.Footnote 28 Of any forceful intervention in the inland there was still no question. A later resident, Sikman, was brusquely treated by the regional chief of Mollo and a Sonba’i prince when he visited the highlands in 1881. Back in Kupang, he recommended that Batavia dispatch a punitive expedition, which led to his firing for disturbing the general policy of noninterference.Footnote 29 At the same time, the various chiefs of the Sonba’i sphere such as Miomaffo, Mollo, and Takaip emerged as rajas on their own account and were acknowledged as such by the Dutch authorities in 1900, adding to the complicated political picture.Footnote 30 From all this it is apparent that Sonba’i does not easily fit into the category of a state in the conventional sense of the word.

But there was still a formal paramount lord called Nai Sobe Sonba’i III, brother of Bau Sonba’i, who was unwilling to give up his prerogatives. In 1903, an internal conflict between various princes in the old Sonba’i lands caused the Dutch Resident F. A. Heckler to intervene. The Dutch officials were stunned by the disrespect shown to the colonial state. One chief said that “Mai Bapa CompanyFootnote 31 talks a lot but does little,” while another one spat on the ground while declaring that the “Company” was unlikely to take action.Footnote 32 An armed expedition made a hasty end to the trouble, but the Dutch soon noted that Sonba’i was a nuisance to their ambitions. The authority of the ruler was still recognized by many people and he continued to receive traditional harvest tribute. Neither the local conflicts of 1903 nor the authority of Sonba’i would have been of much concern in the old days of onthoudingspolitiek (non-intervention policy) in the nineteenth century, but new circumstances meant that a confrontation was in the air.Footnote 33 Governor General J. B. van Heutsz was known as a hawkish politician who intervened incessantly in indigenous affairs and strove to implement Dutch colonial governance in the outer islands. Adding to this, the Dutch so-called ethical policy brought a rationale for intervention to root out perceived misrule.Footnote 34

In August 1905, an incident occurred while the resident was occupied with disturbances on Flores. The available colonial troops were quickly dispatched to Kupang, since the residency’s local resources were insufficient. From their base in Kupang, the troops attacked the centre of Sonba’i resistance in Kauniki. Though without major battles, it was a bloody war, fought in the mountainous and inaccessible interior of Timor where European troops had seldom ventured. As will be discussed in detail below, the Dutch troops arrested Nai Sobe in early 1906, colluding with part of the indigenous elite. Here we should note the fragmented nature of Timorese polities; anticolonialism was less prevalent among Indonesian groups than some patriotic textbooks would like us to believe.Footnote 35 Resistance to Dutch encroachment was always mixed with collusion, which should of course not excuse the exploitative aspects of European colonialism in the region. This was the definite end of the classical Sonba’i realm, and the fallen ruler was exiled to Waingapu on Sumba. He was later allowed to return to the “pacified” Timorese highlands, but not for long. Since he allegedly agitated against the colonial state, he was forced to live in Kupang under surveillance during the last year of his life. He passed away in 1922, more than eighty years of age. Sobe had no children, but his distant kinsman Tua Sonba’i served as raja of Mollo from 1932 to 1959. He harboured ambitions to restore Sonba’i to its old splendour and took a disdainful attitude to the Netherlands during the Japanese occupation of 1942–45.Footnote 36

Similar clashes took place in Belu (Central Timor) in 1906 and Amanuban in 1910. In the latter case the local raja Bil Nope made a desperate last stand at his residence in Nikiniki and was killed after a siege by Dutch troops. After these events, West Timor was considered “pacified,” and was soon to be followed in this respect by East Timor, where a last great rebellion flared up in 1911–12.Footnote 37 The colonial authorities gathered the firearms kept by the local populations and introduced a strict administrative hierarchy with officials called controllers and assistants in the various divisions of the land. Headhunting and slave trading was abolished, roads were planned, passes for foreigners visiting the interior were introduced, regular markets were established, and the power of the Chinese traders was weakened (since they had previously sold arms and ammunition to the locals). People were to stick to fixed settlements and the cattle were to graze at assigned places in order to avoid conflicts over the herds.Footnote 38 Thus the fate of Sonbai falls into a broader pattern affecting Timor at the time under the overlapping governments of José Celestino da Silva in the Portuguese part (1894–1908), and J. B. van Heutsz (1904–1909), who were major representatives of a will to round out the colonial realms and remove any antediluvian obstacles to a modern colonial state.Footnote 39

Local perception and the oral history problem

The foregoing paragraphs have acquainted us with the main events leading to the Dutch takeover. Let us now take a closer look at Nai Sobe Sonba’i III, or Sobe for short. His story did not fail to captivate the interest of those trying to formulate a history that was both Indonesian and Timorese and filled the criteria of heroic struggle against colonialism that could serve educational purposes in the sprawling island republic. The well-known Savunese politician and intellectual, I. H. Doko, among others, wrote extensively about historical figures that resisted colonial encroachment in the Timor region, referring to them as pahlawan-pahlawan suku Timor, heroes from among the Timorese people. One of the main heroes was Sobe, whose career was described by Doko from a mixture of written documents and oral history.Footnote 40 A few later published texts largely repeat his information with some additions.Footnote 41

The war of 1905–1906 is therefore an event that impressed posterity and easily lent itself to Indonesian anticolonial nationalism, and here oral history opened a door. Some twenty oral accounts were collected by the local historian F. H. Fobia in the 1960s, when there were still people alive who remembered the war.Footnote 42 Fobia was part of a research team from Universitas Nusa Cendana in Kupang. Among others he interviewed various mafefa, traditional spokesmen with a fund of knowledge of the past. His interviewees were therefore first- or second-hand witnesses of the events of 1905–1906. The material has been presented in three extensive but unpublished manuscripts, “Sonba’i dalam kisah dan perjuangan” (1984), “Pahlawan Sonba’i” (2003), and “Kisah dan silsilah marga Fobia” (2003), the second of which in particular provides ample details from oral sources. The main witness from the war was Ai Sonba’i, who accompanied his uncle Sobe Sonba’i and was captured with him. He was interviewed in Biloto in 1965, “the tone of his voice being shrill and strong.”Footnote 43

Studies in oral history suggest that narratives of events lying several decades back in time often show contemporary written records to be misleading—either out of ignorance or by design. At the same time, the comparison shows that the oral stories include inaccuracies where memories have changed over time and tend to conform with currently acceptable norms. In the course of one person’s life we have to deal with complex layers of memories that give rise to new meaningful self-perceptions.Footnote 44 Thus oral accounts may represent attempts to make sense of a changing world after the fact. The process of memory selection makes them likely to diverge, sometimes significantly, from contemporary official accounts of the same events. In an interpersonal perspective, the accounts can be manifestations of a “movement,” in this case abortive anticolonial resistance. As such, the accounts define the state of the world as the narrators know it, and justify the narrator’s acts and decisions within the movement.Footnote 45

It is nevertheless important to note the peculiar Timorese context. First, we should note the profession of the informers, that is, what could be expected from them. The mafefa of Timor are professional record-keepers assigned the task of speaking for the lord and memorizing a body of information. Long narrations in formal or ritual speech (natoni), characterized by canonical parallelism are learned by heart.Footnote 46 When I interviewed a mafefa in Mollo, a part of the Sonba’i sphere, in 2004, he provided much information about conditions in his own lifetime. But I could also relate some of his information to persons and events known from European written sources of the nineteenth century, sources that he clearly did not know of. As with James Fox’s studies of oral tradition on the nearby island Rote, one may discern a set of stable narrative particles (names, relationships, wars, alliances, and so on) that tend to be embellished and used in partly new narrations, from place to place and from generation to generation.Footnote 47 Second, and related to this first point, many local societies in the region harbour an intense interest in history in the sense of a perceived past. To outside observers it may seem vague, de-temporalized and interacting with a supernatural macrocosmos. Nevertheless, the past matters, to the degree that some stories should not be told to outsiders—further complicating the assessment of recorded oral narratives.Footnote 48 By collating oral history accounts, one may bring into high relief the contemporary archival documents, which are often written in an official and unreflective style. Taken together, such accounts may question and problematize the “official” version of history.

Here the materials used by Doko and Fobia present interesting problems. Both authors are or were educated intellectuals, and it is not possible to tell in any detail how their views of the matter relate to the outlook of their aged informers. In the process of writing things down, the nuances, hesitations, self-corrections, and other narrative tics are inevitably lost. To an extent, it is possible that the accounts have been streamlined to suit nationalist agendas at the time of writing. Indeed, such a syndrome is to be expected. As Reinhart Koselleck suggests, perceptions of the past are tied to perceived threats and possibilities when facing the future, and are shaped in a dialectical relation to these.Footnote 49 Taking these considerations into account, we shall now scrutinize the course of the war according to parallel Dutch and indigenous accounts. This will be followed by a discussion about the possibilities of interpretation.

Voices of the vanquished?

To a certain extent, diverging perceptions of the Sonba’i-Dutch disputes can already be found in the contemporary mailrapporten, regular reports from the various residencies of the Dutch East Indies. As early as in 1904, before the actual start of the war, a mailrapport provides a few disdainful remarks about Nai Sobe Sonba’i III. In 1898, according to the report, Sobe had paid a visit to Kupang at the invitation of the regional Dutch administration. The resident offered him a tongkat, that is, a ceremonial staff representing delegated princely authority. Tongkats held great prestige and were often preserved over the centuries. The bestowal of the tongkat implied a formal recognition as a subordinate ruler, and suggests that the Dutch tried to increase control over the interior by this time, when they were in the process of surveying the borders with Portuguese Timor. Sobe reportedly answered that he had already received a tongkat, and that a new one was not necessary. He made it clear to the whites that he felt irritated that the Dutch had given such tongkats to his various fettors, or regents, who had therewith been put on equal footing with him. The 1904 report further indicated the perspective of the ruler. He asserted “that since Mai Bapa Company regards it as its right to punish his mountain people, he correspondingly has this right with regard to the Government subjects.”Footnote 50

The tone of the report is undoubtedly disdainful of the Sonba’i ruler. By claiming to have the same prerogatives as the Dutch colonial state, the ruler stands out as somewhat ridiculous and overblown. The theme of vainly upheld pretensions of an Oriental Liliput ruler facing a colonial power is apparently found now and then in colonial literature at the time.Footnote 51 At the same time, the attitude of Sobe as quoted in the report is less outlandish if one considers the policy of nonintervention that marked the colonial state until then.Footnote 52 The Dutch had not intervened successfully in the affairs of Sonba’i since the mid-eighteenth century, and the last expeditions in 1849–50 and 1857 had ended inconclusively.Footnote 53

With the Portuguese restricted to the eastern half of the island and the Dutch hesitant to act outside the Kupang area, politics followed its own rules in the rugged highlands of the interior. From that point of view, Sobe’s claims contain a sense of logic. The Sonba’i rulers had ruled their mountainous realm since at least the seventeenth century with no external attempt to alter the indigenous governance. In 1898, the writing was not yet on the wall, and few locals could foresee the abrupt expansionism that was begun a few years later.

Dutch reports state that the war was triggered by a Sonba’i attack on Bipolo and Nunkurus, two settler villages near Kupang Bay under the direct jurisdiction of the government, on 19 August 1905. This was an area that was mostly settled by people originating from the nearby islands of Rote and, to a lesser extent, Savu, for whom the colonial government had a preference, since they were considered industrious and susceptible to conversion to Reformed Protestantism. The attack cost the lives of thirty-two men, women, and children while sixty-two others were carried away.Footnote 54 A memorandum a few years later indicated that the ruler himself had no actual part of the attack on Bipolo.Footnote 55 The action, known as the Bipolo War, nevertheless strengthened the Dutch resident in his plan to make an end to “the harmful phony rule of the Sonba’i dynasty” altogether, and not just launch a punitive expedition. Were Sonba’i to get away with this aggression, it could have very harmful consequences for Dutch prestige and influence.Footnote 56 At the same time the authorities admitted their ignorance of interior conditions due to their previous onthoudingspolitiek. It was hard to know anything definite about the prerogatives of the Sonba’i lord.Footnote 57

F. H. Fobia records another version of the events from his interviewees. First, the Bipolo War, far from being an unprovoked attack, was caused by the theft of pinang (areca nuts used for chewing betel) and coconuts by Rotenese persons living in Bipolo and Oeana, east of Kupang Bay and under Dutch jurisdiction. These products grew unusually densely at the mamar of Nailete in the Sonba’i land close to the Dutch sphere. A mamar is a stretch of land for plantation situated by a source of water, and the produce is protected by an adat regulation called banu and may only be harvested collectively. Pilfering may be punished by the guardian of the banu or the ruler. Therefore, the incident caused a meeting among the foremost fighters (meo naek) of the Mollo and Fatule’u regions, who deemed the theft a legitimate reason (fanu, also translated as war slogan) for armed retaliation. Such decisions were not a casual matter: there were in fact seven different fanu in Atoni traditions of warfare.Footnote 58 Fobia quotes a piece of ritual speech with its characteristic parallelisms that alludes to the reason of the war: fanu puah Mailete kinen ma’fen, noah Nailete kinen ma’fen (“the reason is that the pinang of Nailete grows heavily, the coconuts of Nailete grow heavily”). The ruler’s nephew Ai Sonba’i related to Fobia in some detail how 760 men under named leaders marched via Camplong towards the Dutch enclave, armed with rifles, spears, blowpipes, slings, and clubs—the last three weapons seldom mentioned in ethnographic accounts.Footnote 59 Having cunningly scouted Bipolo, the warriors attacked the settlement in the evening, with Sobe Sonba’i at the helm. As noted, his personal participation is not mentioned in the Dutch reports. Ai Sonba’i asserted that the number of victims was even higher than in the Dutch report since eighty-three people were beheaded and a number of women and children succumbed in the flames.Footnote 60 The collecting of heads was a prestigious act in Timorese society and often implied the construction or strengthening of a polity.Footnote 61

The contemporary Dutch accounts describe the arrival of fresh troops from the Flores war theatre and the march of the colonial forces towards the interior. On 18 September, the troops came into contact with the war bands of Sonba’i, which suffered some losses in the subsequent encounters. On 3 October, the Dutch reached Kauniki, the ruler’s residence, which was situated by a lofty rock. Although they had expected fierce resistance by the Timorese, the place was found to be deserted.Footnote 62 Some of the Dutch returned to Kupang with their prisoners on 2 November, while the leader of the troops from Java, Captain Franssen Herderschee, was appointed civiel gezaghebber (civil officer) with orders to pacify the land and introduce a new order.

The oral version recorded by Fobia agrees that the superior equipment of the colonial troops soon proved decisive. Hamlets were deserted before the onslaught of the enemy. Ai Sonba’i speaks of Dutch atrocities not found in the colonial reports. Old people, women, and children who were unable to escape were herded together by the troops, severely mistreated, raped, or even killed. They were kept under surveillance like animals, and babies born in the camps did not survive. Dead babies were unceremoniously thrown in the river by the colonial troops. When brought towards Kupang, some prisoners who could not march from exhaustion were killed off and left to die. Women giving birth on the way were offered no assistance.Footnote 63

In the highlands, the fortress at Pulu-Kauniki was destroyed by Dutch cannons and Sobe Sonba’i III fled to another place called Manumuti with his kin and followers. The Dutch commanding officer sent a message to the ruler, requesting his surrender within forty-eight hours. Sobe replied: “Tell the white monkey in trousers who likes creeping around the native land of other people, and who likes to pick the crabs of the sea, that I will not speak with you.”Footnote 64 Moreover, he used the strength of the knowledge (Indonesian, ilmu) inherited by his line to fight the Dutch. The centre of the kingdom, Kauniki, was usually called Fatu pup-molo, hau pup-molo Bi Kauniki, meaning “The stone that is yellowish on the top, Bi Kauniki.” The significance of this appellation is that the rock of Kauniki, with all the eucalyptus trees growing there, are visited by bee swarms every year. Sobe now used the bees as a means of defending himself. With his supernatural knowledge, he ordered the bee swarms to attack the Dutch soldiers. The colonial troops flee head over heel to escape their stings. The Sonba’i lord could thus escape their clutches for the time being.Footnote 65

Returning to the Dutch reports, these make clear that Sonba’i resistance continued unabated for some months. Groups of so-called rebels, sometimes up to a hundred people strong, attacked the troops of Franssen Herderschee but suffered high casualties. Dutch losses were reportedly insignificant. The end of the resistance came in the beginning of 1906, as described in a Dutch mailrapport:

In Mollo [part of Sonba’i], no resistance was offered until now, and, as previously told, the fettors assisted in capturing and tracking the refugees—the fettor of Besiana in particular made a good example. The fettor of Netpala, under whom Besiana adhered in name, did not seem to be that reliable judging from the recent rumours that the pretender-emperor and his adherents had found shelter in his territory, without him having told us about it. When quite certain information about his refuge arrived, the civil administrator decided to march up there with a column.

The place of refuge was the kampong Biloto in Netpala. Having arrived at Besiana, the pretender-emperor and his wives went there to report himself to the civil administrator, being escorted by the chief of Biloto after the fettor of Besiana had told these persons that it would be fruitless to hide anymore since all access roads (to Belu and Noimuti) had been occupied.Footnote 66

The surrender occurred on 6 February. This event marked the end of the Sonba’i realm. A few local chiefs fled to the Portuguese enclave of Noimuti, and a certain Chinese refugee also kept away from the colonial authorities. But from the Dutch point of view, the affair was accomplished.

Here, too, the informants of Fobia provide a rather different story: Nai Sobe stayed at Basmuti near the village Biloto in the company of his two wives. There they were protected by the Mella clan who ruled as fettors in the area. Later on, however, the people of Besiana reported to a Dutch lieutenant about the ruler’s whereabouts. The end of Sonba’i in this version is quoted as follows.

According to information that the author [Fobia] received from various sides, the Dutch troops, knowing that the Mella clan hid Sobe Sonba’i III in Biloto, wished to attack the Mella clan in Biloto. However, through various intensive machinations, the Dutch troops abstained from attacking Biloto. By means of several tricks, king Sobe Sonba’i III was attracted by the argument that the Dutch wished to make peace. Sobe Sonba’i III was brought to Kauniki with honours, but after he arrived at Kauniki, the Dutch, far from making peace, took Sobe Sonba’i III prisoner and brought him to Kupang for interrogation together with Ai Sonba’i, Neno Sonba’i, Baob Sonba’i, Beke Sonba’i, Bete Bani, Toto Smaut, Baki Koy, and Eko Mnune.Footnote 67

According to a member of the loyal clan, Leonard Mella, who was interviewed by Fobia, the Mellas were forced to pay a fine of fifty horses for their assistance to Sonba’i. The Dutch gave the horses to the Oematan family of Besiana for their service as informers.Footnote 68 The strongly nationalist published work of I. H. Doko gives similar circumstances. It is unclear from Doko’s text where he received the information, but the context suggests oral informants rather than archival sources. We may quote the relevant passage:

The emperor Sobe Sonba’i III retreated and established himself in Biloto in the land of Mollo. The Dutch proceeded with their dirty chastisement. Huku Oematan, the fettor of Besiana, was sent by the Dutch to the emperor with an offer to arrange a negotiation. He came forth from his place of residence and was brought with great ceremony before Captain Franssen Herderschee in Kauniki. The emperor was trapped. He and the heroes were surrounded, arrested, and brought as prisoners to Kupang. Thus ended the story of the forceful and gallant struggle of Sobe Sonba’i III.Footnote 69

After the capture of Sobe, Doko mentions the Dutch mopping-up operations against the rulers’ adherents. Among other things, a patrol arrested the Chinese Tji A Man who had purveyed guns and ammunition to Sonba’i. The Kupang authorities somewhat perfidiously hanged Tji A Man, although one of his fellow countrymen had arranged for a lawyer to be summoned to defend his case.Footnote 70 The Dutch behaviour vis-à-vis Tji A Man after the arrest is not commented upon in the original colonial reports.

The mopping-up operation and the collection of firearms is the focus of a long account by Fobia, for which he relies on family traditions, especially an interview with Noh Fobia, a kinsman who was present at the event. A number of warriors and lords in Mollo plainly refused to heed the commands of the Dutch officer who is again addressed as “white monkey,” with the argument that the shotguns were theirs and not handed out by the Dutch. They issued their own legitimate declaration of resistance, quoted in Dawan and translated by Fobia:

Hey, white man, Dutchman. Heaven above watches and bears witness, the earth stares and bears witness. A long time ago we came together and met in Kupang, Olain Lilo, and Bakunase.Footnote 71 We already agreed that if you brought kains [loinclothes] and jackets, axes and cutlasses, we brought well-packaged beeswax and stems of sandalwood so that we could barter, sell, and buy. But if there is an issue or incident in the following day or night, if you load the rifle in secret and you bring ammunition secretly, if you hone your sword and lance secretly, move against me and restrict me, tomorrow or the day after tomorrow, with yellow glow and black smoke, then the sword and the lance shall fight and you and I shall compete day and night, as you and I follow the backside of the hill, you and I follow the river, until you remove your foot and leave my land.Footnote 72

A hundred colonial troops subsequently moved from Kauniki to Nefokoko in Mollo. A sharp encounter followed in which the Dutch Lieutenant De Vries was allegedly wounded in the forehead. Several colonial soldiers were wounded. After losing two meo (prominent warriors) the Timorese withdrew to a more strategic location, but resistance soon evaporated and the main instigators were later captured by the colonial authorities.Footnote 73 The incident is briefly mentioned in a Dutch report; the account is rather similar but makes no mention of wounded on the Dutch side.Footnote 74

The Problem of Comparison

A comparison between the written and oral versions of the war is instructive on several levels. The basic course of the conflict is the same in the two categories of sources. A Timorese attack on Bipolo is followed by a forceful Dutch invasion that pushes back local resistance. The Sonba’i ruler has to flee and hides from the colonial troops for a while, but is finally arrested and exiled. However, there are several episodes that are at complete variance with each other. These are not only details, but also vital matters such as the cause of the war, the presence of Sobe Sonba’i at Bipolo, the behaviour of the Dutch invasion force, and the circumstances of Sobe’s arrest. When discussing parallels and contrasts, it is worth recalling the fundamental difference in outlook. The Dutch reports are not meant to be published or made known outside a small circle of administrators. They are written according to established bureaucratized norms, providing detailed accounts of politically important “facts.” On the other hand, they also acknowledge that the colonial administration had access to a very limited fund of knowledge about the interior, which complicated the decision-making process. Moreover, the Timorese of the highlands spoke Dawan which, although an Austronesian language, is entirely different from Malay, which was the standard means of communication on the coast. It is therefore to be expected that the Dutch reports left out important aspects for the simple reason that they had no means to fully know the Timorese mindset.

In the oral history accounts of the Timorese spokesmen, on the other side, local memory has preserved personal and, from a Western perspective, sometimes trivial details unlikely to make it into the contemporary reports. Still, some six decades passed between the events of 1905–1906 and the interviews undertaken in the 1960s. The precolonial world of these narratives is defined from principles of hierarchy and the supernatural world that perfectly explain some of the details that a Western observer might find irrelevant or naïve. But just as important, the narrators were influenced by the colonial and postcolonial eras they lived through.

Unstable Narratives of Colonial Conquest

Several particulars in the accounts recorded by Fobia highlight these points. The theft of pinang and coconuts by colonial subjects being the fanu or cause of the war might be a historical event, but its significance is symbolically increased by the important role of pinang as a gift to rulers: to give sirih pinang (serpinão) implies paying deference. Pinang and coconuts are sometimes mentioned in pairs as royal crops.Footnote 75 But there is more to it. Referring to this incident, the interviewee Ai Sonba’i asserted to Fobia “that the Rotenese were not aware that they were ridden by the Dutch in order to bring conflict between our Indonesian peoples and dredge the riches of our fatherland.”Footnote 76 Thus, even as he provided a logical and justifiable Timorese explanation of the war, the spokesman expressed a commonly held idea in postcolonial Indonesia: that the Dutch maintained control through a divide et impera policy. Similarly, when describing Dutch atrocities towards the old people, women, and children, Fobia relates how tears came in Ai Sonba’i’s eyes as he uttered: “If the Rotenese and Savunese had not followed the Dutch, then we would not have attacked each other. But since the Rotenese and Savunese imitated the Dutch, calamities befell us.”Footnote 77 His emotional outburst might also be seen against the assertion in a Dutch memorandum that he personally murdered two Rotenese, an incident that was part of the background of the Dutch intervention.Footnote 78

As is common in historical narratives from Timor and indeed much of Southeast Asia, supernatural occurrences play a role. While the colonial report makes it clear that the Sonba’i stronghold of Kauniki was abandoned by its defenders, and makes no mention of any incidents there, the Timorese version has swarms of bees putting the Dutch soldiers to flight through the supernatural intervention of Nai Sobe Sonba’i III. This accords well with other accounts of Sonba’i history that give the Sonba’i lord a strong influence over the forces of nature. He regulates sunshine and rainfall and can turn into a python or a tree stump. In 1927, long after the end of Sonba’i, a grand sacrificial ceremony was held in which Sonba’i was asked to intervene after a multitude of mice ruined the harvest.Footnote 79 This was at a time when there was no Sonba’i ruler, so that the line was thought to lead a spiritual and non-temporal existence. Whether colonial soldiers were bested by bees or not is less important for the Timorese understanding of their own political culture. Rocks and mountaintops have a great role as sanctified strongholds of Sonba’i and other Timorese kingdoms, which gives a particular edge to the story. The theme of bees warding off an enemy is found in other Timorese kingdoms such as Ambeno and Wehali, where the Portuguese are the adversary. Traditions from Fatumean in East Timor even describe rituals to activate the bees. It is also found in other places of maritime Southeast Asia, for example in the Balinese text Babad Buleleng, where the troops of the renowned ruler Gusti Pañji Sakti fail in their enterprise to conquer South Bali due to bee attacks.Footnote 80

Nothing comparable to Sobe’s defiant reply when summoned to surrender is found in contemporary sources. It is impossible to say if he replied in that way, or at all (and Dutch underlings or interpreters may not have dared render his words before the face of the white tuan, or “master,” as the Dutch were known). But the wording is interesting as reflecting a counter-discourse vis-à-vis the colonial emphasis on modernity and disdain for native primitivism. The outward appearance of the Dutch commander is the object of ridicule for the Timorese who never wore trousers but rather waist-cloth. He is moreover likened to a creeping monkey, an animal sometimes associated with slyness but still unreliable and unruly. Monkeys are frequently tricksters in Timorese fables but they are nevertheless out-tricked and often succumb in the end.Footnote 81 One may recall Anthony Reid’s conclusion that indigenous sources of early modern Southeast Asian history very rarely make positive statements about Europeans but oscillate between neutral and hostile views, with the latter gaining ground.Footnote 82

The most controversial point of comparison between colonial and Timorese accounts is the circumstances of Sobe’s arrest. Did he surrender of his own free will or was he betrayed and captured? It has been suggested that I. H. Doko’s published account is influenced by nationalist stories about the capture of the Javanese resistance leader Diponegoro in 1830.Footnote 83 Diponegoro had also been promised safe conduct by the Dutch but was nevertheless arrested during negotiations.Footnote 84 That would be another interesting confluence between oral history and postindependence all-Indonesian national discourse. Nevertheless, deceitful conduct of that kind was not uncommon in Dutch dealings with political opponents. One does not need go as far as Java: the treacherous capture of a Sonba’i ruler in 1752 was well-remembered in Timorese tradition, and the Dutch resident of Kupang planned unsuccessfully to capture the Sonba’i lord in 1837 through trickery.Footnote 85 European untrustworthiness was therefore a theme in the collective memory. The quoted Dutch report of the alleged surrender is not very detailed, leaving plenty of room for different interpretations. Was the ruler misled by false promises of reconciliation and guarantees of personal safety, as Fobia’s and Doko’s texts suggest? There are a few circumstances that support such an interpretation. Six years after the war, in 1912, a memorandum was penned by the resident of Kupang, C. H. van Rieschoten, with a version of the story that is not quite compatible with the contemporary mailrapport: “The excursion to this territory made good progress. After the resistance in the Sonba’i lands had been put to an end (Takaip, Taibokko, Banu, Tefnai and Pasi), [the troops] also visited the lands of Mollo (which extradited the pretender in February 1906), Amakono and Gunung Mutis, which also belonged to Sonba’i; then it was the turn of the lands situated at the east coast.”Footnote 86

In 1932, the controleur of Middle Timor, Ch. Th. Weidner, wrote a survey of the old Sonba’i land of Mollo based on local information. Discussing the status of the principal chiefs of the territory, he remarked:

The fettor of Bijeli (the headman of the Mella family) was as such the house warden of Sonba’i and was, together with the Sainam family (wardens of the land in Miomaffo) very attached to the imperial house of Sonba’i. In the time of the last Sonba’i (exiled to Camplong and later deceased), Netpala already entertained higher political aspirations and did not lift a finger to support Sonba’i, who was pursued by the Company. This person was even extradited to the Company by Besiana. The Mellas have never forgotten this.Footnote 87

Finally, a 1948 memorandum by W. G. H. Reijntjes, a Dutch official, claims that “the Keizer was taken prisoner in his house at night.” After his arrest, two stones were placed before his house in Kauniki, under which the Sonba’i powers were symbolically buried, ostensibly for good.Footnote 88 Though these reports seem to broaden the possibilities of interpretation of the war, they still leave several questions unanswered. The rapid disintegration of resistance in face of the rather modest Dutch invasion force contrasts with the successful or semi-successful resistance on some previous occasions. Noteworthy is the behaviour of Besiana in colluding with the Dutch troops to capture Sobe Sonba’i. A factor is the disunited nature of the Sonba’i clan, which is hinted at in another indigenous account. As related above, Sonba’i was split into two major branches in the nineteenth century, Nasu Mollo being the main ruling representative of the junior branch in Fatumnutu. His great-nephew Tua Sonba’i was appointed raja of Mollo in 1932 and provided an extensive account of his family history to Reijntjes. The account is noteworthy for leaving out the history of the senior branch, avoiding details about the 1905–1906 war. For the narrative about this branch the weal and woe of Sobe was less relevant.Footnote 89

The idea of split loyalties among the highland elite is also suggested by a study of Besiana. A memorandum by the leader of the expedition, Franssen Herderschee, surveys the three branches of the Oematan clan, which ruled Mollo, noting that Besiana was considerably weaker than its senior cousins in Netpala and Nunbena. At the time of the war, the fettor of Besiana was an in-law of the Rotenese chief in Oesau, one of the settlements near the coast under Dutch jurisdiction, and had a Rotenese mother.Footnote 90 Possibly such connections influenced the acts of the fettor of the small and vulnerable territory. As noted by McWilliam, the more extensive a Timorese realm was, the more prone it was to fragment when the centre for some reason weakened.Footnote 91

As can be seen, the later colonial texts are at variance with the official report written at the time of the event. Rather, the quoted passages essentially accord with the oral Timorese narratives of the 1960s. The Sonba’i ruler was, in these various versions, extradited rather than surrendering voluntarily. The formal, matter-of-fact style of Western colonial reports seldom entices the reader to doubt the content; however, this case does raise the question of the reliability of official data. Were the details of the capture of Sobe altered in order to reinforce the image of an awe-inspiring and efficacious colonial incursion? By portraying the appropriation of the ruler as voluntary, the legitimacy of the violent takeover was apparently strengthened.

Concluding Remarks

The horseman on the Kupang street, with his selimut flying behind him and his pistol pointed towards the enemy, embodies three broad aspects discussed in this article. As a person, he represents a noble and heroic precolonial past supposedly recovered by oral sources. As a monument, he stands for a will to domesticize historical figures to fit national striving. And his placement is due to a colonial apparatus that made Kupang the regional centre and engendered the very modes of expression that enabled the monument. Facing this is the body of textual records. As an aspect of the colonial ordering force, the archive expresses the professed aim of the colonial state to achieve rust en orde—peace and order. Full control had to be implemented in order to transform local Indonesian society according to rational norms. For the decision-makers in The Hague and Batavia, the system of loosely dependent princedoms that sprawled across the East Indian archipelago impeded progress, and their chiefs and rajas, had to be either fully subordinated and domesticized, or else done away with. The Sonba’i lord was considered a historical anachronism, as implied by the Dutch insistence in terming him “pretender-emperor” leading a “phony rule.” Why a bloody war had to be fought to eliminate this “phony rule” the documents do not try to explain. In a region where literacy was almost nil, there were no written challenges to the colonial voices.

Oral history may, on the other hand, bring recognition to groups of people hitherto ignored. The people interviewed in the 1960s held some status in the old Timorese hierarchy, and their statements were not necessarily those of the common man. Their testimonies are nevertheless important for providing an idea of precolonial society as perceived in the collective memory. The oral accounts suggest that Sonba’i was akin to what Jane Drakard has called a “kingdom of words.” The Minangkabau kingdom of Pagaruyung on Sumatra, the Klungkung kingdom of Bali, and the Wewiku-Wehali realm of central Timor were all ritual-laden kingships with limited conventional political powers, although the first two were based on written texts in contrast with Sonba’i.Footnote 92 Involved in a web of ritual and genealogical relationships among the elites of Sumatra, Bali-Lombok, and Timor, and deeply meaningful in the local perception of past and present, these realms were invisible to the colonial observers who often found them impotent, anachronistic, and irrelevant.

Still, a comparison between Dutch and Timorese accounts of the colonial conquest will not generate definite answers of wie es eigentlich gewesen, to use Ranke’s much-quoted phrase. The perceived truths of the recorded reminiscences may lie more in “actuality” than “factuality,” and their relevance may come more from an ever-changing present than from the historical past.Footnote 93 In expressing anticolonial sentiments, modern collectors of stories and, to an extent, the storytellers themselves, were in the end dependent on modes of expression derived from the culture of the colonialists. In this sense, it is still a matter of “speaking for” rather than “speaking with” the vanquished. Nevertheless, a close parallel reading of the course of the 1905–1906 war destabilizes the colonial discourse in two ways. First, it calls into question the factual reliability of the production of official data. Issues about the origins of the war were left downplayed, atrocities against the civilian population were muted, the murky circumstances of the capture of the ruler were glossed over. Second, the oral history accounts suggest the rationale of anticolonial struggle and indigenous discourses of power. Reminiscences of an upheaval that must have had been a historical turning-point in the collective memory were processed over six decades into a meaningful set of decisive episodes. That these episodes were not the choice of the colonial intruders is certainly to be expected.